Untitled, 1964

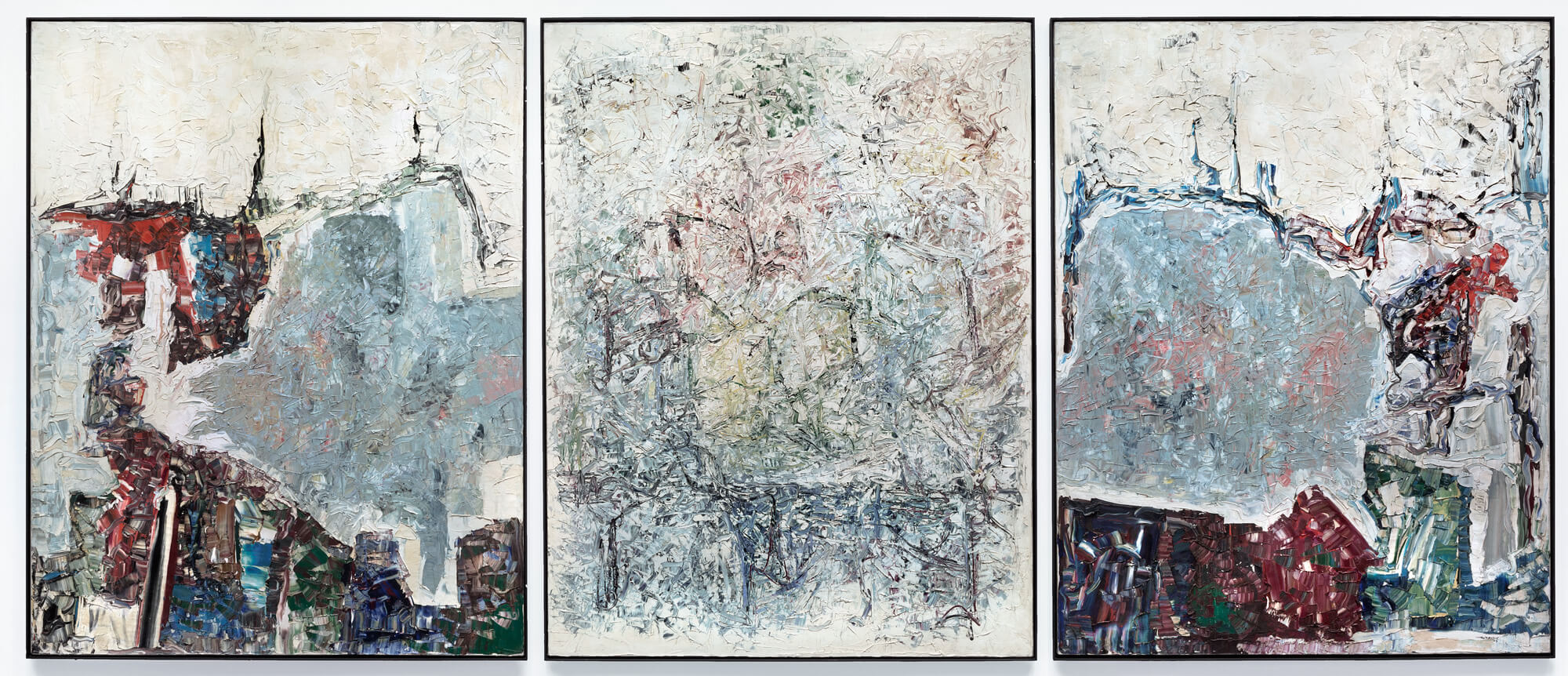

Jean Paul Riopelle, Untitled (Sans titre), 1964

Oil on canvas, 276.4 x 214.5 cm (panel A); 275.5 x 214.7 cm (panel B); 275.5 x 214.5 cm (panel C)

© Jean Paul Riopelle Estate / SOCAN (2019)

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

Jean Paul Riopelle enjoyed producing vast three-part compositions, as did his romantic partner Joan Mitchell (1925–1992), the American painter with whom he spent almost twenty-five years. Their paintings are often compared, as in the case of Riopelle’s Untitled (Sans titre) and Mitchell’s Girolata, both from 1964. According to Riopelle scholar Michel Martin, each painting is intended to evoke a seascape. Not only are these works contemporaries, today they rest in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

In this painting, panels one and three are related, both in colour (red, blue, grey, and brown) and in the way paint is applied, using a palette knife with broad strokes in the coloured sections and narrow ones in the grey. Section two in the centre, however, is much more uniform in the tone and intensity of colour. In contrast Mitchell’s Girolata is a triptych unified by shape and hue, focusing on grey, black, and white, with some green, beige, and pink accents. In Mitchell’s piece, the eye moves comfortably from one section to another, which is not the case in Riopelle’s work. In Untitled the dark painted passages seem to purposefully rupture the flow from one section to the next, imbuing the work with a kind of assertive monumentality. The abstract shapes in this triptych appear to resist containment within the framed sides of all three canvases. Contrary to Riopelle’s piece, Mitchell’s work seems calmly self-aware of the limits of the painted surface, with the shapes organized centrally in each of the three sections. Riopelle’s composition is therefore closer to the all-over abstraction recognized as American Abstract Expressionism—the pictorial elements, which are more or less uniformly distributed over the surface, look to press beyond the physical confines of the work.

When Abstract Expressionism sought to distinguish itself from European modern art, it did so via the moderate size of its paintings. In Europe, artists used mural (that is, very large) paintings to convey a social or political message. Examples include The Raft of the Medusa (Le Radeau de la Méduse), 1818–19, by Théodore Géricault (1791–1824), which measures nearly five by seven metres, or Liberty Leading the People (La Liberté guidant le peuple), 1830, by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), measuring two and a half by three metres. The Americans, according to the formalist critic Clement Greenberg (1909–1994), adopted an intermediate scale between mural and easel painting to distance their works from the large-format realist European tradition, often containing political messages. Yet, with Untitled, Riopelle demonstrates that he does not seem to care much about the format-distinction debate. Cut into three almost identical panels nearly three by two metres each, Riopelle’s does not shy away from its own monumentality.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements