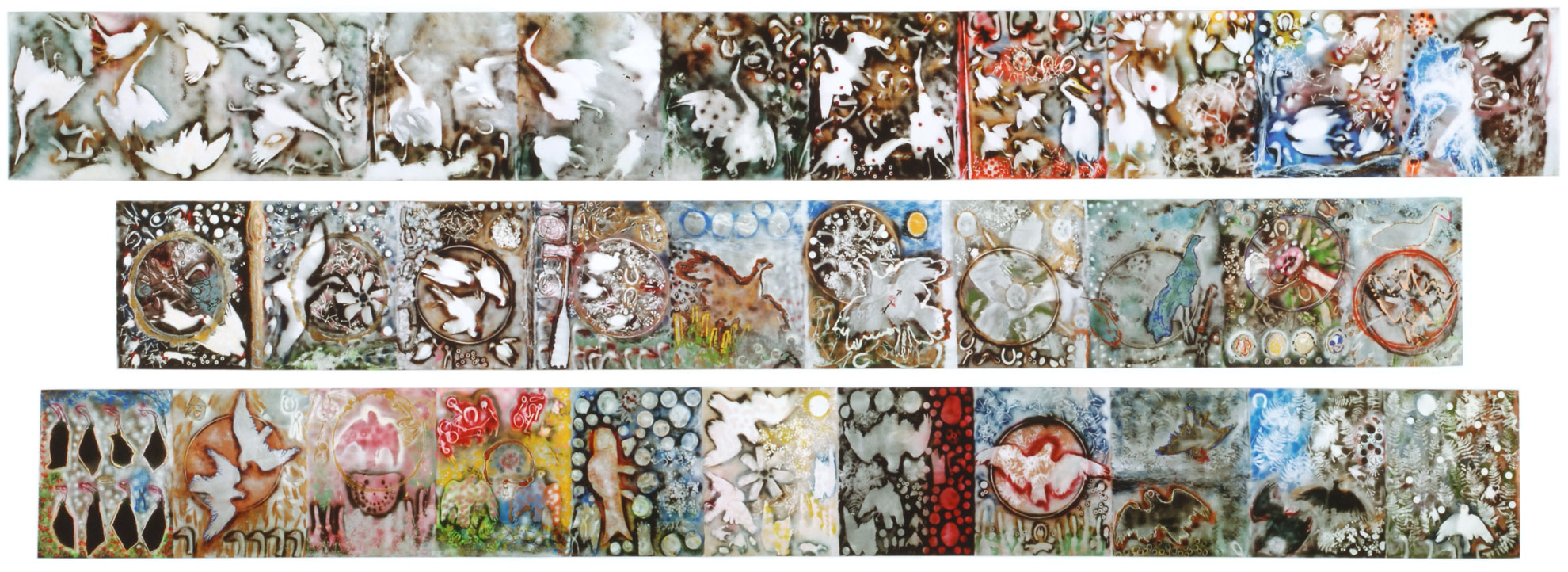

Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg, 1992

Jean Paul Riopelle, Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg (L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg), 1992

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas

155 x 1,424 cm (1st element); 155 x 1,247 cm (2nd element); 155 x 1,368 cm (3nd element)

© Jean Paul Riopelle Estate / SOCAN (2019)

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

When Jean Paul Riopelle learned of the death of Joan Mitchell (1925–1992), his companion of twenty-five-years, he set to work on a monumental work comprised of thirty paintings for her, which he titled Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg (L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg). The work, which unfolds like a “succession of animal paintings” was not painted with a palette knife, a tool long associated with Riopelle, but with spray paint, a medium he used near the end of his career.

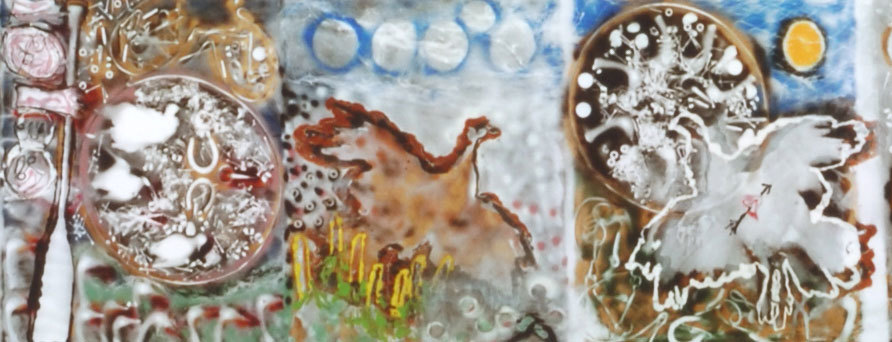

Riopelle created the work by laying its panels flat on a table, one after another. In producing Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg, a work more than ten metres long, the artist used up three bolts of canvas. As he unrolled each segment he would paint. On it he placed various objects—some more unusual than others—including dead geese, horseshoes, radiator fans, various tools, bolts, nails, and screws. Riopelle sprayed each item with paint to make a real-life cut out of the object, leaving a silhouette or trace. This evocation of an absent item is particularly significant when one considers that the work was made in the context of the death of a loved one.

The title of the composition derives from the fact that Riopelle called Mitchell his “Rosa Malheur,” an ironic pun referring first to the famous Second Empire Parisian painter Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899), and second to Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919), the famous Marxist, socialist activist, and theorist opposed to the First World War, who died in Berlin in 1919 during the German revolution that led to the democratic parliamentary republic known as the Weimar Republic. Riopelle was no more interested in the painting of the first Rosa than in the political ideas of the second; however, from the latter he obtained the habit of coding hidden messages in his written correspondence, as Luxemburg had done from prison. In this way, the Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg must be understood as a coded work, revealing in symbolic form several episodes drawn from his and Mitchell’s time together. For example, the work includes references to Riopelle’s encounters with the artist Sam Francis (1923–1994), his stage set for a play, and Mitchell, who is represented as a bird pierced by an arrow.

Riopelle painted his Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg over three months in his studio on Île-aux-Oies. This impressive painting, “whose signs and codes recount, as if as a watermark, his encounter with Mitchell,” was created “in a single extended burst of inspiration.” While the visual effect is particularly festive—with the lively composition showing many dancing shapes on the surface, highlighted by bright, shimmering colours—the piece is nevertheless one of mourning.

Riopelle reflected with these words: “Today, there is no longer any Rosa Malheur. There is not even a Rosa Bonheur anymore. All the Rosas are dead.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements