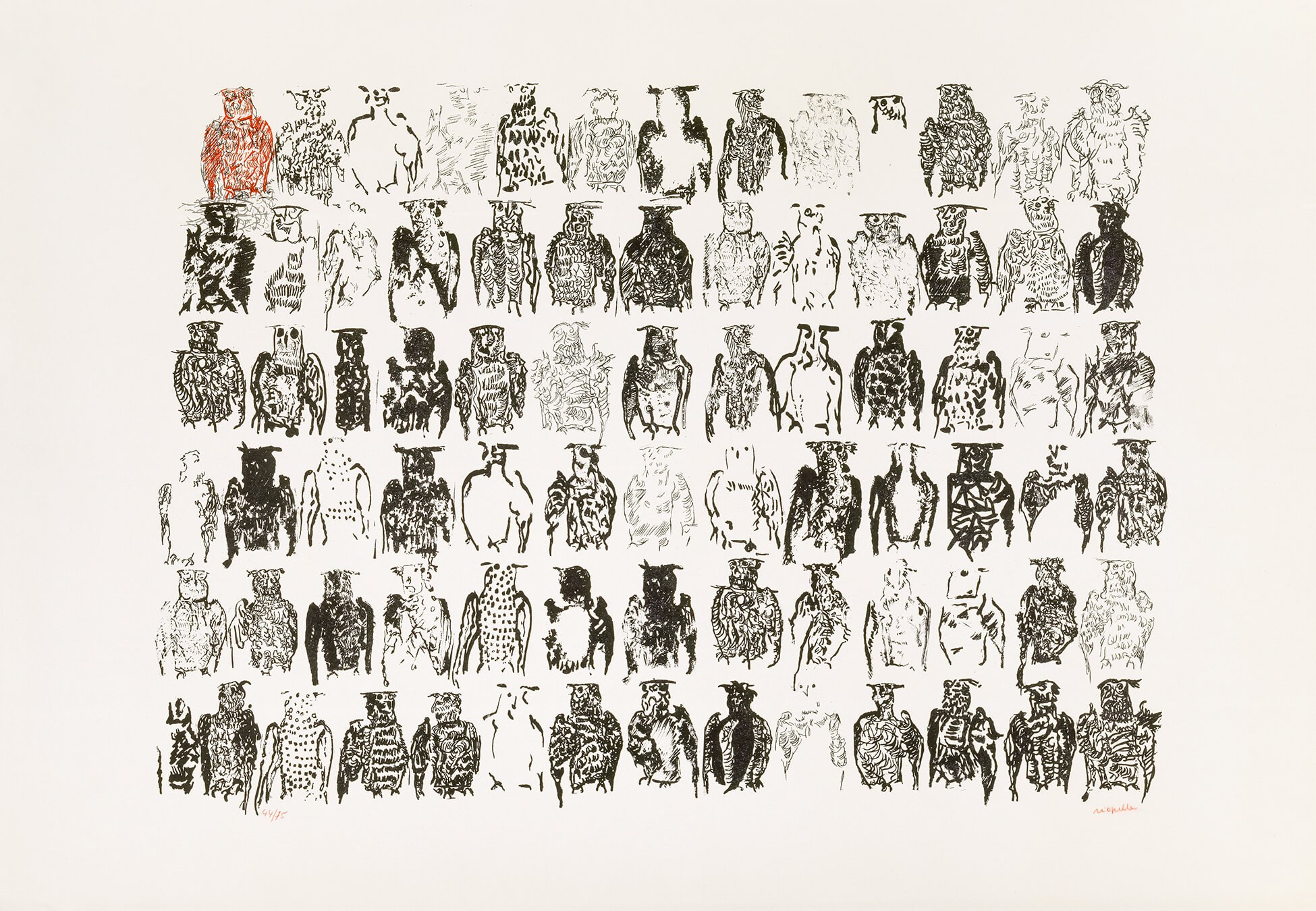

The Owls, 1970

Jean Paul Riopelle, The Owls (Les hiboux), 1970

Lithograph, 44/75, 76.4 x 109.9 cm

© Jean Paul Riopelle Estate / SOCAN (2019)

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

It is nearly impossible to estimate the number of times Jean Paul Riopelle depicted owls over the course of his career. In this one lithograph alone, The Owls (Les hiboux), there are seventy-nine of them, arranged in six rows. Riopelle so often depicted owls that one might assume that the subject fascinated him. However, his statements about them suggest quite the opposite:

If people ask me why I drew two thousand owls, I would say, “It’s to make lithographs.” But in reality, it’s having made the two thousand owls that interests me. Not because they’re owls. I don’t care about owls. For all that, they are not symbols. I didn’t think about what they meant when I made them. I made them.

During his training with Henri Bisson (1900–1973), the young Riopelle created a painting titled First Owl (Hibou premier), 1939–41. This early attempt was inspired by a stuffed bird, most likely a product of Bisson’s hunting. While not great, it is not Riopelle’s worst painting from the period. He painted freely with less restraint than in his other compositions. The influence of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) is obvious, even though Riopelle’s interest in the painter was forbidden by Bisson’s teachings.

During the 1970s and after over twenty years of dedicated abstraction, the theme of the owl returned in full force to Riopelle’s art along with figuration more broadly. Works on paper, as in The Owls; paintings in oil on canvas as in Owl–Jet Black (Hibou–Jet Black), 1970; and sculptures, as in Owl-Rock (Hibou-roc), 1969–70 (cast in bronze 2010), showcase Riopelle’s incredible skill in a diversity of media. These works mark the return of figuration into Riopelle’s oeuvre. In The Owls, the multiplication of portraits, each distinctive, depersonalizes the owl. In Owl-Rock, the unique detail of the sculpted form accentuates its imposing presence and singular identity. Riopelle’s bronze cast sculptures are characterized by his finger imprints, which were left on the clay and serve to represent traces of the artist’s act of creating, or doing.

Soon after the owls began to appear in his work, so did the snow geese of Cap Tourmente. Each year during hunting season, they arrived by the thousands and Riopelle, an avid hunter, would set out to meet them. Once the hunt was complete, he would create hundreds of images and drawings. Of this work he remarked, “The important thing is to do.” All these works with bird subjects are evidence of a practise that is supported by nature and serves as the pretext for creation. For Riopelle, there was no gap between his abstract work and his figurative work. Both were a part of the same act, the same “doing.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements