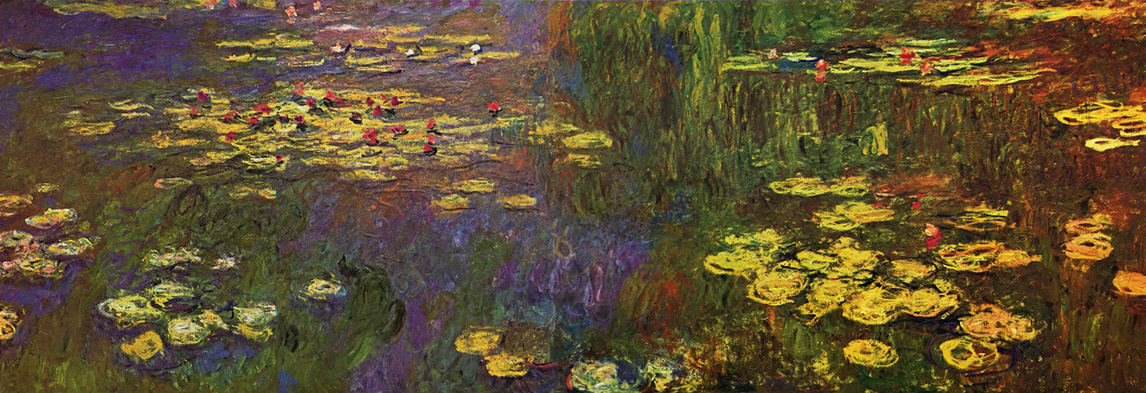

Pavane (Tribute to the Water Lilies), 1954

Jean Paul Riopelle, Pavane (Tribute to the Water Lilies) (Pavane [Hommage aux Nymphéas]), 1954

Oil on canvas, 300 x 550.2 cm (triptych)

© Jean Paul Riopelle Estate / SOCAN (2019)

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

The great triptych, Pavane, is one of Jean Paul Riopelle’s most famous paintings, not only because it has been widely exhibited (in Paris in 1955, 1960, 1968, and 1981; at the 31st Venice Biennale in 1962; in several Canadian museums in 1963, 1991, and 2002; in Tel Aviv in 1970) but also because it received immense critical acclaim. The piece is named after a ceremonial slow dance that was performed in costume at the Spanish court during the sixteenth century. In this composition, comprising three panels, texture plays an essential role while a gentle cadence seems to guide the overall flow of colour.

As he had done with Untitled (Sans titre), 1949–50, Riopelle created the work by squeezing oil paint directly from the tube onto the canvas surface. He applied pigment seemingly spontaneously, guiding the motion of the paint with a palette knife to build up a deep and imperfect automatist style of impasto. Today, Pavane is proudly owned by the National Gallery of Canada.

The painting looks back to the last great series of works by Claude Monet (1840–1926), Water Lilies (Nymphéas), 1920–26, found at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. Its alternative title, Hommage aux Nymphéas, and the explicit reference to Monet are attributed to Riopelle’s close friend the critic Patrick Waldberg. Riopelle’s rhythmic palette knife strokes and combinations of shimmering colour give the work an organic impression. It is as if the piece quivers with movement in a similar manner to that of the Water Lilies (Nymphéas). This vast composition depicts, without seeking to mimic, the living materials of the natural world: water, plants, flowers, and above all else, fleeting light.

In Pavane Riopelle went against the ideas of the French art critic Georges Duthuit (1891–1973), who asked the artist to create “voids, spaces where thought can and should move.” In response, Riopelle created a scene where movement prevails over everything else, from top to bottom and back again. The problem contemplated by Duthuit, that of a canvas which could appear full yet empty, escaped Riopelle. Even the white palette knife strokes, seen in the lower left and right sections of the far panels and in the upper half of the centre panel, do not create voids. They become simply another feature of the composition and rest harmoniously among the coloured strokes.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements