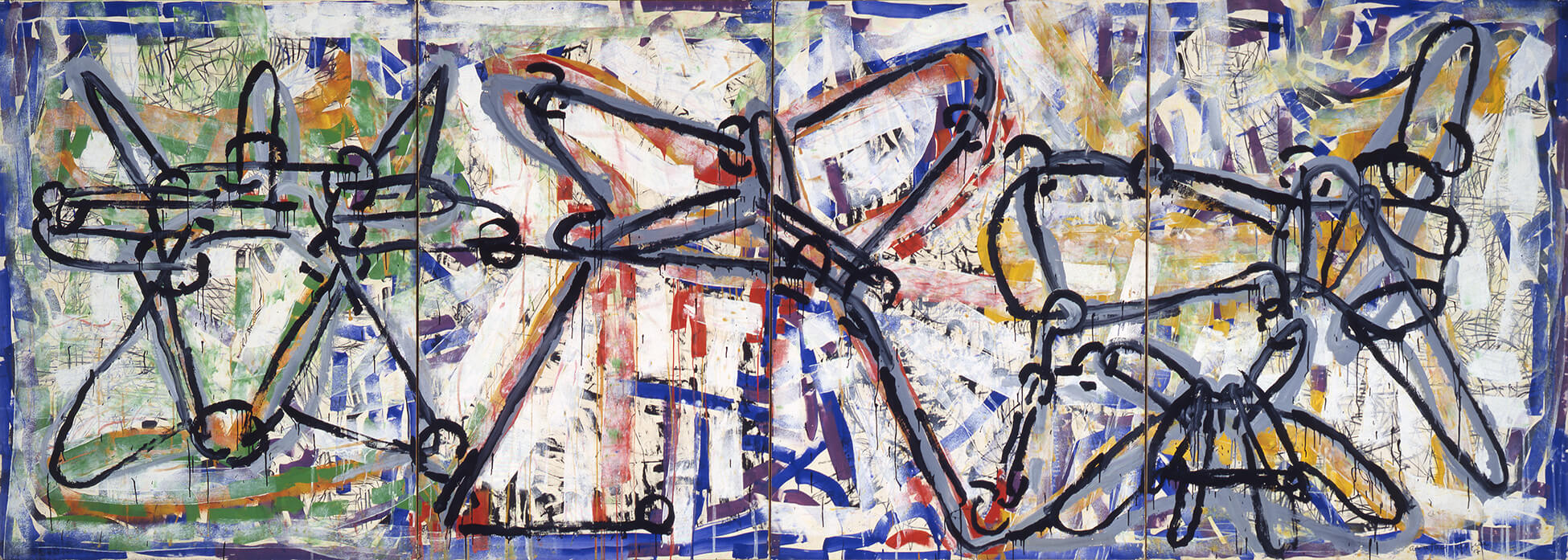

Avatac, 1971

Jean Paul Riopelle, Avatac, 1971

Acrylic on lithograph mounted on canvas, 160 x 448 cm (quadripartite)

© Jean Paul Riopelle Estate / SOCAN (2019)

Galerie Maeght, Paris

Avatac is a vast four-part composition that draws inspiration from Inuit string games. Starting in the late 1960s and until the early 1970s, Jean Paul Riopelle became fascinated by these games; he saw Inuit succeeding in creating a visual and impermanent language that was, according to the art historian Ray Ellenwood, “figurative and yet not strictly representational.” The non-objective shapes that populate the painting summarize Riopelle’s understanding of the essence of the games.

In the game called ajaraaq in Inuktitut, a person either alone or with a partner manipulates a string to create various configurations. Soon, such images as a dog team, a tent, a drying rack, a snow shovel, glasses, or a hare escaping a hunter come to life. Emulating this Inuit form of play, in Avatac Riopelle presents supple black lines, almost alive, that wriggle along the surface of the multilayered composition; a textured background subtly echoes these dominant shapes.

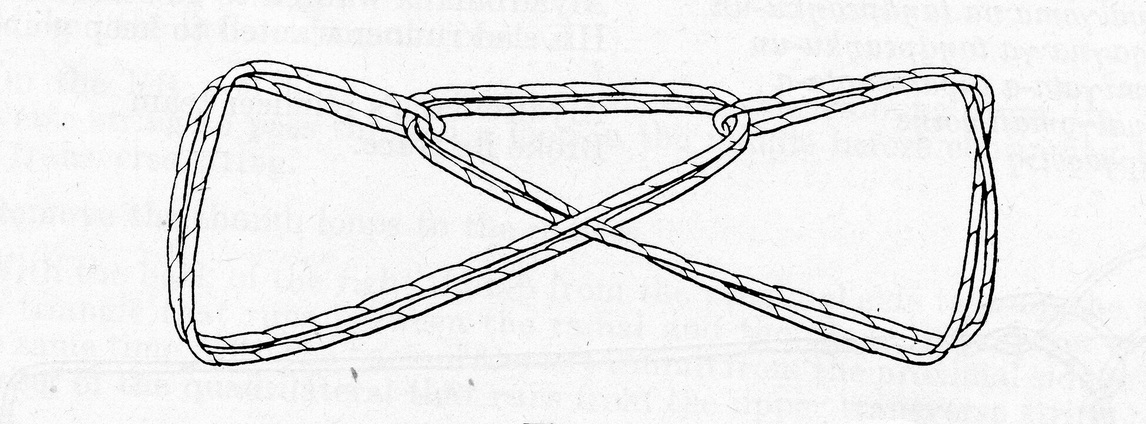

An avatac, as referred to in the title of the work, is a float used in traditional hunting made from a single sealskin. The device is fastened by wooden plugs at either end and is connected to a harpoon by a rope made of sinew. The tool is used to keep the hunter’s catch afloat or as a beacon to locate a marine mammal that has been harpooned underwater. In Riopelle’s composition, however, the energetic motifs seem detached from their original name and use; the result, as interpreted by Michel Martin, is a “broad landscape plan,” animated by playful forms, for which the artist invites the viewer to “decode the sign.” Riopelle would dedicate an entire exhibition and a series of paintings to this style: Strings and Other Games (Ficelles et autres jeux) was presented at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris and at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1972.

Another reason that Inuit string games may have caught Riopelle’s attention is that their players take a simple line and interpret it figuratively. After a few twists and turns, a piece of string between the fingers becomes a form open to interpretation. Riopelle did not conceive of his artistic approach as abstract and therefore found the game to be commensurate with his own intentions. For him, art was not about imitating nature, like a model to be reproduced, but of encountering it. Beginning with colour, form, and matter, he travelled toward nature without claiming to accurately represent it. In the Inuit string games, as in Riopelle’s work, this encounter is allusive.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements