Jean Paul Lemieux was an affectionate and acute observer of his country. Living through most of the twentieth century, he amassed a rich trove of influences from Europe, the United States, and Canada. In his work as a draftsman, painter, illustrator, and muralist, he forged a distinctive artistic personality that, beginning in 1956, brought him international recognition. His contribution to the history of art takes him beyond Canada’s borders and places him in the ranks of the great Nordic Expressionists.

Early Influences

For Lemieux, the acknowledgement of one’s influences is essential to the development of an original artistic personality. His taste was eclectic and very definite, and he felt affinities with numerous painters. Like many of his generation he owed his first awareness of international currents in art to the New York magazine Vanity Fair, which under the auspices of its editor Frank Crowninshield (1872–1947) brought together famous illustrators, writers, painters, and photographers in a series of separate colour supplements devoted to the leading creators of modern art.

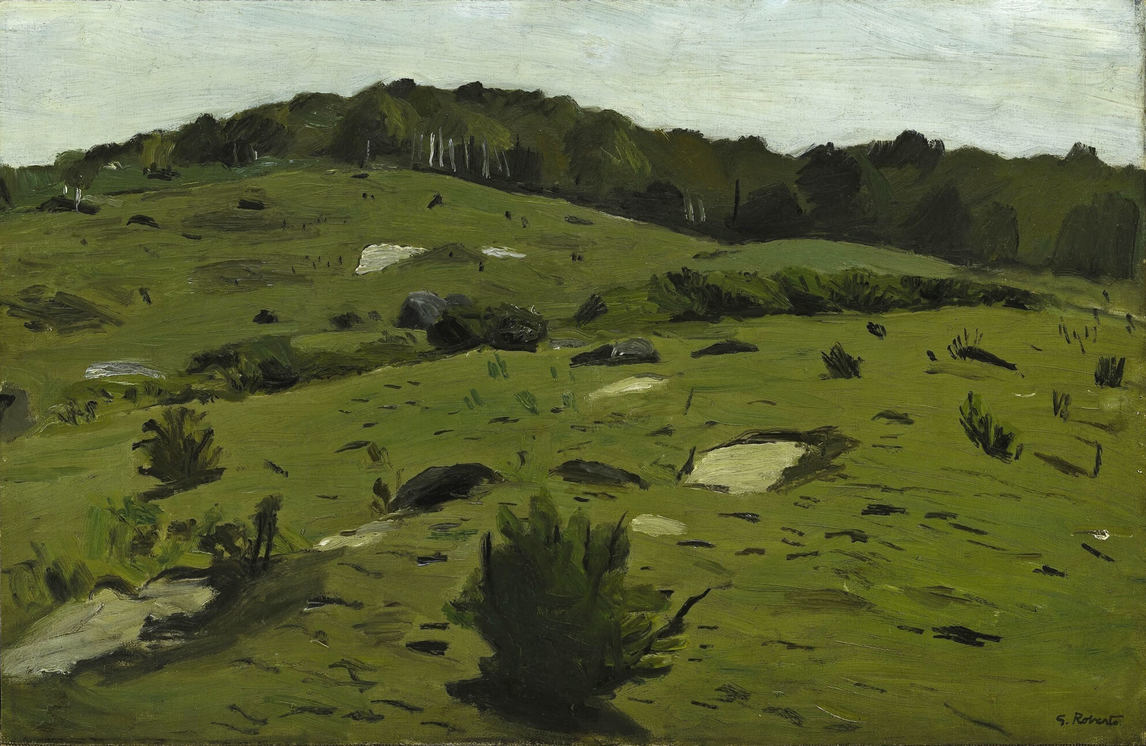

But Lemieux’s first direct influences were Canadian: the Group of Seven, and in particular Edwin Holgate (1892–1977), who joined the group in 1930. These painters sought to convey the emotions inspired in them by Canada’s natural beauty, and allied themselves with late-nineteenth-century European Symbolists and Post-Impressionists such as Edvard Munch (1863–1944), Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), and Émile Bernard (1868–1941). Lemieux’s Afternoon Sunlight (Soleil d’après-midi), 1933, is imbued with the expressive force they aimed for, rejecting the kind of naturalism that seeks only to replicate nature. Lemieux also admired the work of Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974), whose influence can be seen in the muted, earthy poetry of Landscape, Eastern Townships (Paysage des Cantons-de-l’Est), 1936, a composition that recalls the deliberate, measured side of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906).

Lemieux’s interest in American Social Realism is evident in The Village Meeting (L’assemblée), 1936, which depicts a municipal gathering in a rural environment and pushes realism to the point of caricature. He uses all the traditional details: calendar, spittoon, devotional images on the walls, the austere dark cross of the famous temperance movement and the portrait of its founder. The painting implies enough ridicule and sarcasm to raise the same questions as those asked about the works of Grant Wood (1891–1942), Ben Shahn (1898–1969), Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975), or John Curry (1897–1946): is it meant to celebrate the traditional scene, or to mock it—or even condemn it?

Primitivism

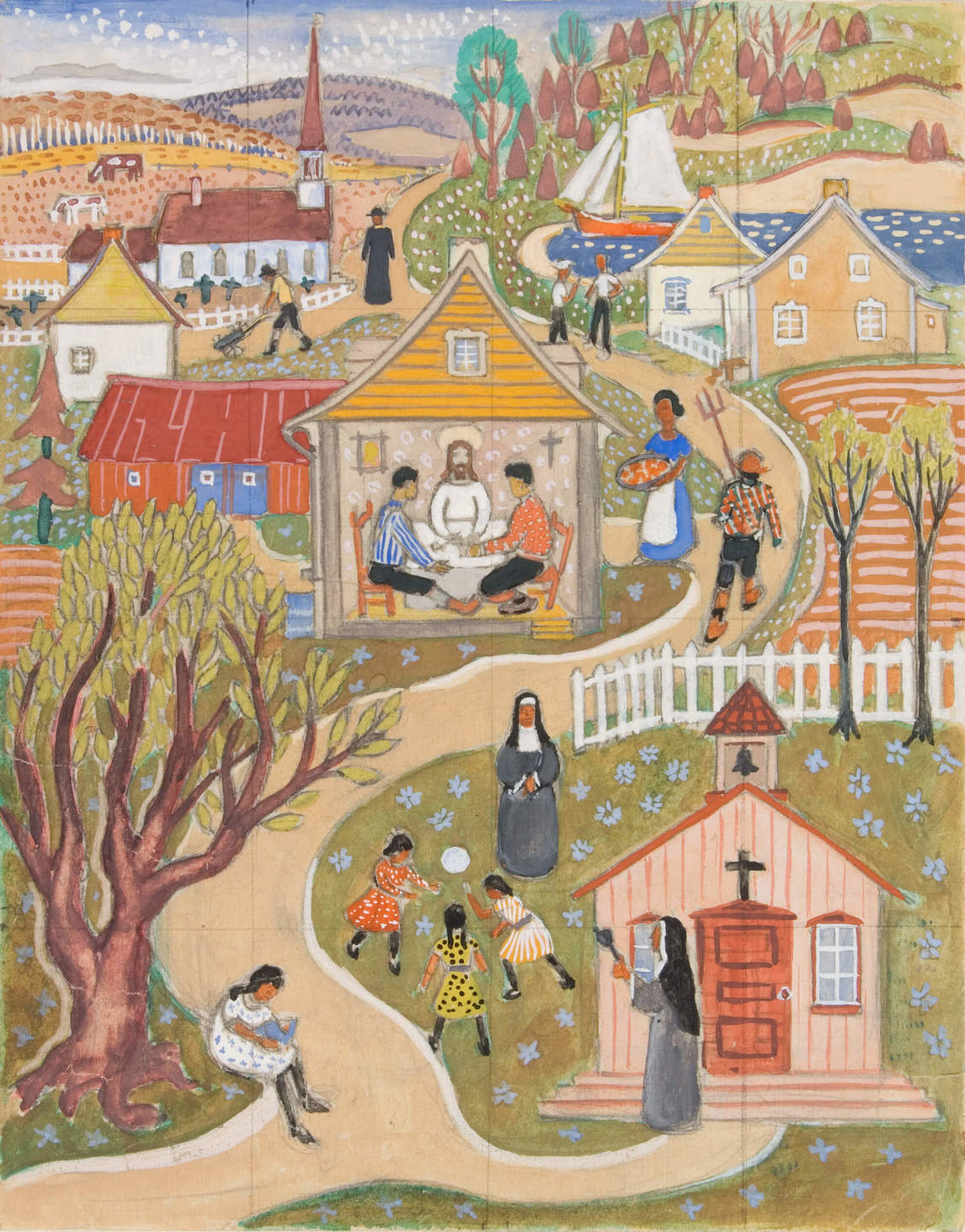

The paintings he made in his narrative primitivist period (1940–1946) are Lemieux’s often humorous way of reacting to the moral rigidity prevalent in Quebec at this time. Using vivid contrasting colours and precise drawing to capture even the smallest detail, Lemieux tackled the superstitions of the French-Canadian people and the power of the Catholic clergy. The Disciples of Emmaus (Les disciples d’Emmaüs), 1940, Lazarus (Lazare), 1941, Our Lady Protecting Quebec City (Notre-Dame protégeant Québec), 1941, and Corpus Christi, Quebec City (La Fête-Dieu à Québec), 1944, link the ordinary details of daily life to events of greater significance and a more complex reality.

Variations on the theme of religion, these works draw their visual inspiration from the tradition of the ex-voto offering, the Holy Scriptures, or the Catholic liturgical calendar. Formally, they share a pyramidal construction set within a vertical frame. The high- or low-angle perspective orients the viewer’s eye along a winding path from the bottom to the top of each composition.

In the preparatory sketch for The Disciples of Emmaus, executed in gouache, we can still see the lines Lemieux drew to facilitate scaling up the image to a larger format on canvas. In the finished painting, the scene could be interpreted as a delicious bit of irreverence: the artist has obscured the sacred character of the biblical story of the evangelist Luke by placing it in a setting of everyday activities in a Laurentian village. For the meaning of this work to be clear, it has to be seen in the context of the renewal of religious art that took place in Quebec during this time. This was a movement to integrate the sacred into ordinary life. The primitive art of Giotto (1266/67–1337), for instance, was offered as a model of that integration; the goal was to create works of art that would democratize the evangelical message by including images drawn from the contemporary world or from life in the countryside.

Classic Period

A slow process of germination between 1945 and 1950 led to the blossoming of style that would make Lemieux famous. His classic period lasted from 1956 until 1970. The “synthetist” art of the Nabis, inspired by Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and by the proto-Cubism of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), formed the basis of his new aesthetic identity.

Lemieux had not forgotten the Gauguin paintings that impressed him in Boston in 1930; they had made him aware of art’s immense symbolic power. In this respect a work like The Ursuline Nuns (Les Ursulines), 1951, shows that his concept of the primary aim of art was similar to that of the Symbolist Maurice Denis (1870–1943): “Remember that a picture, before it is a warhorse or a nude woman or a particular anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colours arranged in a certain order.” In The Ursuline Nuns Lemieux follows Cézanne in the use of cavalier perspective, a technique he had begun to work with in the preceding period.

Empty spaces and a bare horizon line crossing a plastic, flat field were among the key features of Lemieux’s classic period, such as in The Conversation (La conversation), 1968. This purification of imagery would develop further as the painter began to compose pictures using long diagonals, creating an unstable equilibrium. His deserted landscapes, most frequently staged in the winter, are charged with feelings of time passing, of death, of the human condition, and of the loneliness and smallness of human beings before the infinite horizons of the vast landscapes of Canada.

His palette was now limited to just a few pigments: olive green, white, shades of ochre, earth colours, and red. Blue is entirely absent because, the painter said, it seemed to disturb the balance. He preferred to approximate it using only white, black, and small amounts of green. More a valorist than a colourist, Lemieux used subdued, in-between shades that accorded with the meditative nature of these canvases. The softened tones parallel the evocation of memory, and the monochrome or oligochrome (reduced) palettes add to the effect of immensity created by the horizontal format, and sometimes intensify it, as in A Day in the Country (Une journée à la campagne), 1967, a painting that belonged to Lemieux’s friend, the novelist Gabrielle Roy.

For a long time Lemieux had painted sur le motif: directly and immediately from nature, often outdoors, but from the end of the 1950s on he worked in his studio, without models, using only daylight for illumination. “I am painting … an interior world. I have stored up a lot of things.” His free approach was in many ways similar to the practice of abstract painters: “You are guided by the picture much more often than you guide it. And that can lead to results completely unlike what you may have intended or planned.”

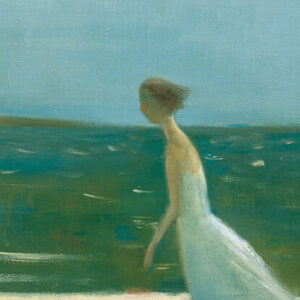

The cinema is no stranger to Lemieux’s art. The revelation of Hollywood movies experienced by the young adolescent Lemieux, who lived with his mother and siblings in California, can be seen in the later bold framing and panoramic effects of the mature artist. In Ocean Wind, 1963, for example, blue is heightened to such an extent that it creates the illusion of a vast screen in which the eye loses itself. The horizontal action of the blowing wind has a cinematic effect, like a long tracking shot that moves from left to right. The fragile feminine figure walking into the wind is a true point of pictorial tension.

Nordic Expressionism

During the last twenty years of his life, in what is referred to as his Expressionist period (1970–1990), Lemieux’s painting conveyed his dark, tragic vision of the tormented historical era he was living through. He had decried the appearance, several decades before, of a troubled art generated by disturbed times, speaking at that time of Cubism, abstract art, and Surrealism. His kinship with the Nordic Expressionists now began to dominate his work as he studied and emulated Edvard Munch (1863–1944), Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980), Georges Rouault (1871–1958), and even Ivan Albright (1897–1983), the American magic realist painter, whom he found very impressive.

In 1971 Lemieux returned to drawing in graphite, pen and ink, and felt pen, which he had not done so intensely since the 1940s. He also uses oil wash, looking to regain lightness and spontaneity in his pictorial studies, and also to keep a record of his apocalyptic visions. One such record is the notebook of drawings he titled Year 2082, 1972. It was around this time too that he returned to illustrating books, something he had done in his student years. His illustrations for La pension Leblanc by Robert Choquette (1927) and Le manoir hanté by Régis Roy (1928) were reminiscent of woodcuts or lino prints, with their black forms sharply defined against the white paper, and the staccato rhythms of the linear elements texturing the compositions with shadow and light. Four decades on, to illustrate La petite poule d’eau by Gabrielle Roy, he made lithographic prints of some twenty small pictures inspired by the novel. He made similar engravings for Jean Paul Lemieux retrouve Maria Chapdelaine (1987) and Canada-Canada (1984–85).

In the 1970s the contemplative serenity of the landscapes in oil that Lemieux had painted in the previous decade gave way to canvases in which dark, dense masses cover almost the entire picture plane. Playing with tonal contrasts, these works make use of red, black, and blue backgrounds for the human characters, who face front, their expressions conveying sadness, pain, fear, or anguish. “The essential element in my last paintings is the person,” Lemieux explains. “The landscape is his setting. If you could have a world without human beings, the landscape would be the same. But the presence of man changes everything. It is the place of the human within the universe that matters. The person finds his footing, finds himself, in the landscape.”

![Art Canada Institute, Jean Paul Lemieux, Untitled (Soldier) (Sans titre [Soldat]), 1982](/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/art-books_10_jean-paul-lemieux-untitled-soldier-contextual.jpg)

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements