Jean Paul Lemieux’s unique painterly vision and ardent defence of Quebec’s cultural heritage earned him a broad following. His landscapes, with their infinite spaces and the figures that bring them to life and dramatize their loneliness, made their mark on the Canadian imagination when they were painted and continue to do so today. The modernist aesthetic and universal appeal of his work are celebrated by the public and are also of great interest to scholars of art history. These accessible and instantly recognizable paintings represent Jean Paul Lemieux’s deeply human response to the fundamental questions raised by the aesthetic investigations of his time.

Choosing Quebec City

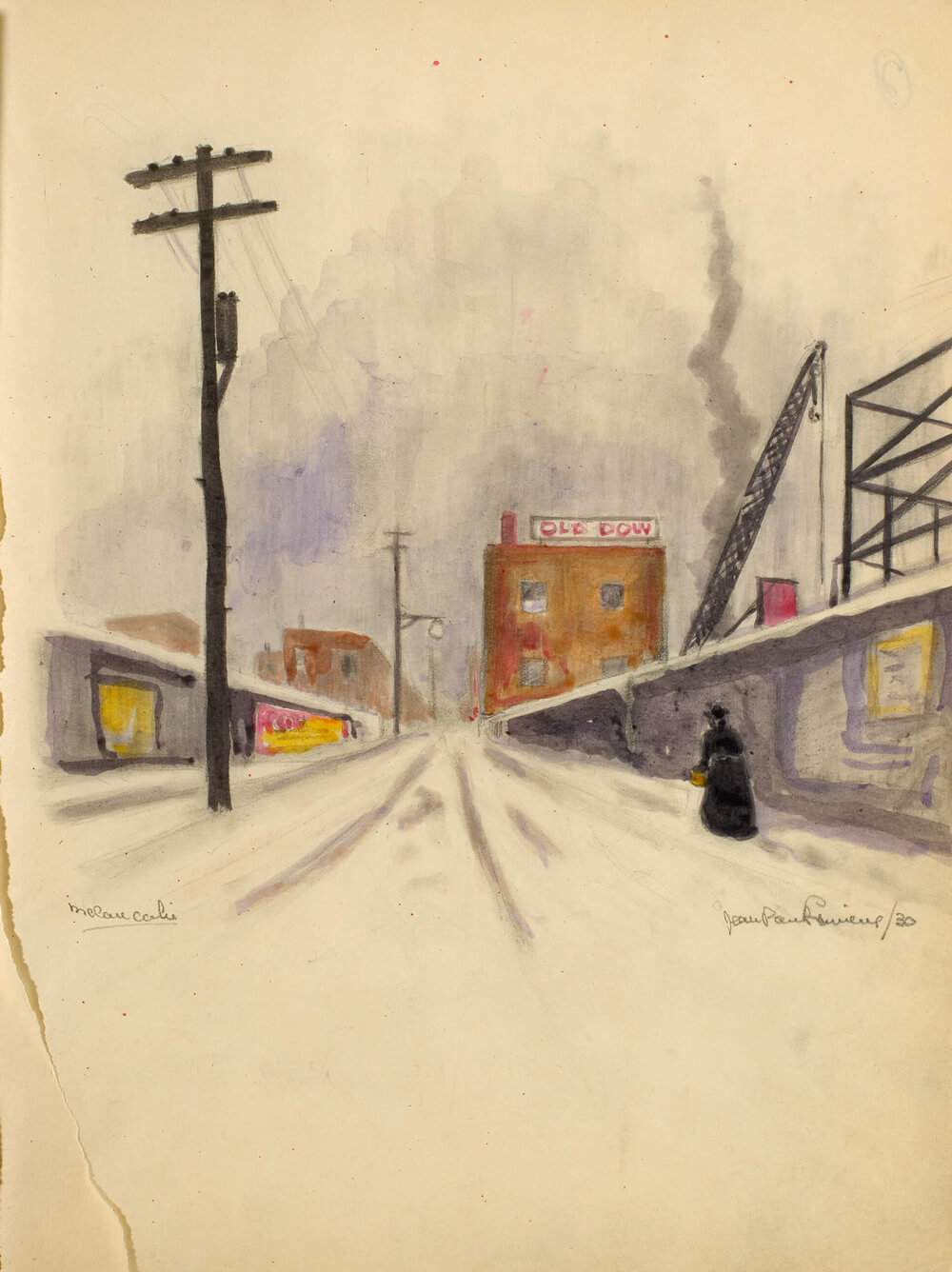

Jean Paul Lemieux would not have chosen to be born anywhere but in Quebec City, an enchanting old walled town, and he lamented the disappearance of its charm as modernization advanced. But he never grew tired of painting his city-muse and city-museum, where he was born and where he would die. He spent most of his life either in the city or not far away from it. At least thirty of the paintings he created after he returned permanently in 1937 showcase its beauty, while at the same time they bear witness to the patient evolution of his style, which is revealed when one compares January in Quebec (Janvier à Québec), 1965 (right), painted in his later, classic era (1970–1990), with Corpus Christi, Quebec City (La Fête-Dieu à Québec), 1944 (below), from his earlier, primitivist period (1940–1946).

From the beginning of the twentieth century Montreal and Toronto were the most important centres in the rising artistic culture of Canada. When Jean Paul Lemieux decided to make his birthplace his permanent home and embarked there on a triple career as painter, teacher, and critic, he showed a remarkable spirit of independence. He was always in touch with the latest advances in painting and teaching as they were occurring in Montreal in the 1920s and 1930s, and was certainly aware that that city was at the heart of the Canadian art scene, as it had been since the middle of the nineteenth century. With the establishment of the Society of Canadian Artists in 1867, and the Art Association of Montreal (now the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) in 1880, Montreal had definitively replaced Quebec City as the most important art centre in Canada.

Quebec City was now more a centre of political than of cultural power. However, the creation of a school of fine arts in 1922 and the Musée de la province de Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) in 1933 undoubtedly had an influence on Lemieux’s decision to settle there. Yet, a disheartening observation he made shortly after his arrival may convey some sense of the isolation experienced in the capital: “Exhibitions of paintings that tour the country never come to Quebec City, for the simple reason that there are no galleries with the necessary conditions of light, neutral background walls, etc.… And so we miss out … on a lot of exhibitions that could educate us and awaken an interest in the beauty of art.”

American Inspiration

Lemieux’s progressive opinions were published widely in both the Quebec and the English-Canadian press in the years between 1937 and 1951. He was one of the first French-Canadian critics to advocate an openness to the art of the United States: “If, as seems certain, America is to be the new world capital of art, we must take our proper place beside our English compatriots and our American neighbours.”

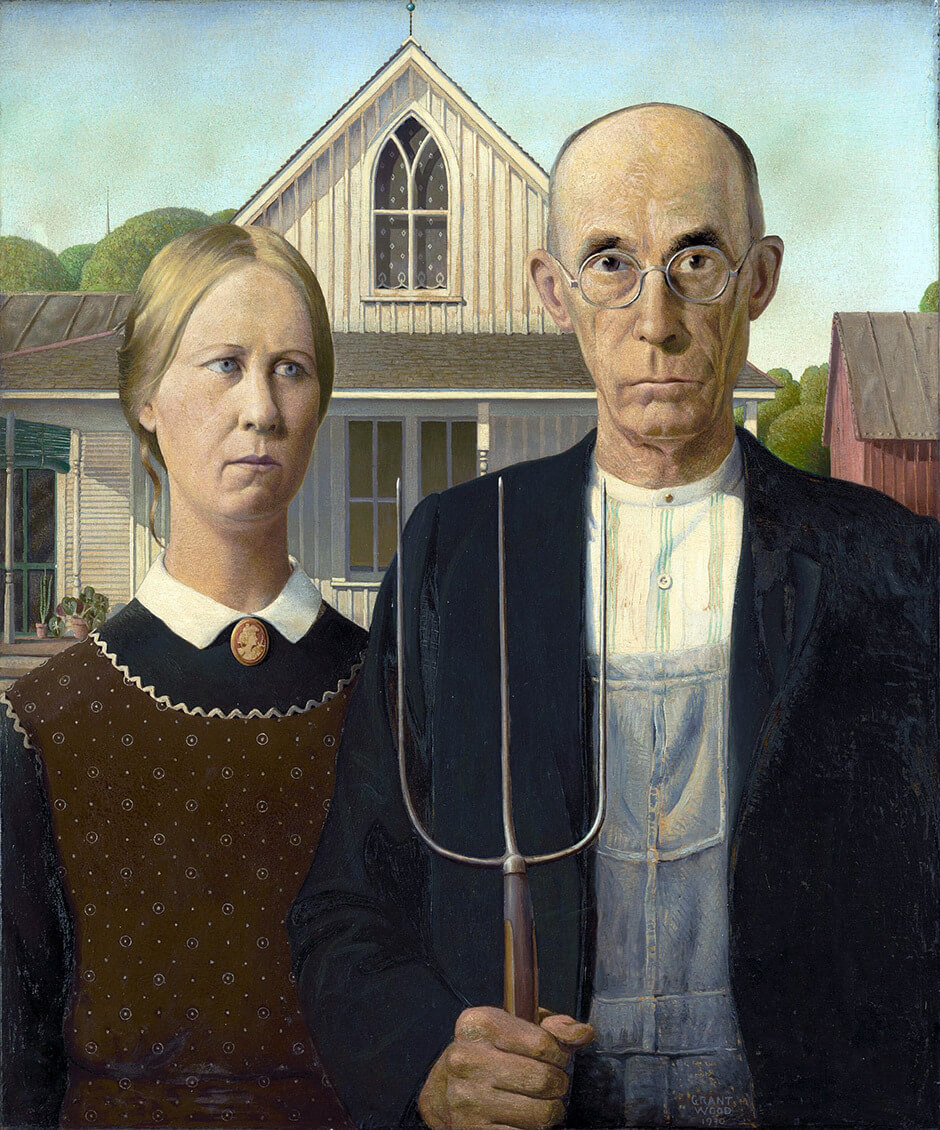

When Jean Paul Lemieux assessed the quality of artists who were working in Quebec, he asked, “Do we have a Diego Rivera, a José Clemente Orozco, a [Thomas Hart] Benton or Grant Wood, to name only a few of the important artists now working in Mexico and the United States? … We have Suzor-Coté and Clarence Gagnon, but they are primarily landscape painters… Their paintings are slavishly faithful to the subjects they depict. They never stray from that path, never turn aside to pursue a more daring interpretation, to create a more original synthesis, or to seek a deeper understanding of the essences of things.”

Art was a precarious occupation, and to counter that insecurity and the prejudices against artists, Lemieux advocated the American model, citing the example of the Federal Art Project run by the Works Progress Administration, which offered grants to artists working on government buildings. “In the United States the government provides work for artists, employing them to paint murals in public buildings, universities and schools…. Besides covering large empty surfaces with colourful compositions, sometimes showing scenes from the history of the U.S. state in which they are located, sometimes illustrating science or the arts, these murals are highly educational; they are seen and admired by multitudes of people…. Why should we not do the same here?”

Lemieux’s admiration of American artists was a key influence in his decision to paint murals. In 1949, he painted a preparatory study for a mural entitled “Québec,” which never materialized. However, the city of his birth would be the subject of another mural project, commissioned by the Université Laval, for the entry hall of the Health Sciences Building, where it can still be seen. Three metres high by five and a half metres wide, this work was completed in 1957. Lemieux made a series of preparatory sketches, the last of which, a study in oil on canvas, has been preserved intact. Unlike the narrative aesthetic he had planned for his first mural project, this one shows the austerity of forms characteristic of his classic period (1956–1970).

Lemieux was sixty when he completed his last mural, Charlottetown Revisited, 1964. The composition is refined to simplicity, but warmed by luminous colours that contrast with the marked severity of the characters, their elongated shapes swathed in black and wearing top hats. Their geometric silhouettes are in harmony with the minimalist neoclassical architecture of Province House, Charlottetown. A similar composition is found on the Prince Edward Island page of the book Canada-Canada, published in 1984–85, which Lemieux illustrated.

An Advocate for Canadian Artists

The subjects Lemieux reflected on in his critical writing—the democratizing and social functions of art, its importance as outreach, the isolation of regional artists—were central to the discussion at the Kingston meeting known as the Conference of Canadian Artists in June 1941, which had been organized by Lemieux’s friend André Biéler (1896–1989) in close cooperation with artists in the United States. This important event (which led to the founding of the Federation of Canadian Artists) featured Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975), the American Regionalist, as guest of honour.

In a letter responding to Biéler’s personal invitation to attend the conference, Lemieux described some of the problems faced by artists in Quebec. “For French-speaking Canadians there is a long list of issues that need to be addressed: the education of the public in matters of art, the preservation of traditional and folk art, exhibitions, propaganda, etc. This meeting will be extremely helpful, especially for those of us isolated in Quebec City and barely scraping a living behind our battlements.” In conclusion, Lemieux suggested that Biéler should also approach Marius Plamondon (1914–1976), Omer Parent (1907–2000), Jean Palardy (1905–1991), and Alfred Pellan (1906–1988).

Despite the fact that Lemieux was not present at the Kingston conference, he was asked to join the national committee that was set up to ensure that its recommendations were implemented. One of the proposals was to create a national art magazine, and in October 1943 Maritime Art, founded three years earlier, became Canadian Art. Between 1942 and 1947 Lemieux contributed numerous articles about the current art scene in Quebec. The pan-Canadian activism in which he was a participant would lead to the creation of the Canada Council for the Arts in 1957.

French Heritage

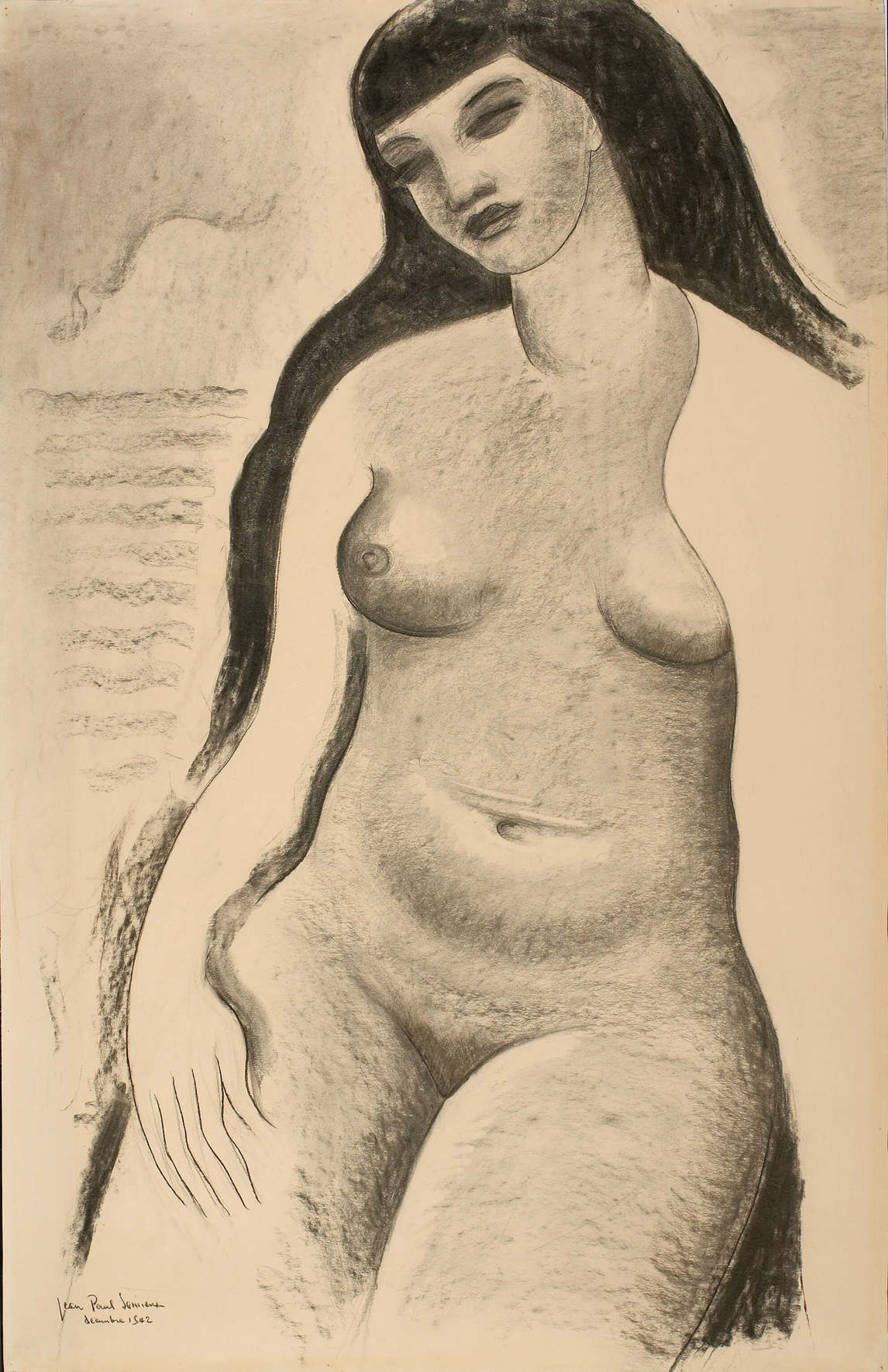

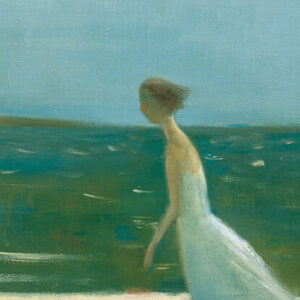

As an internationalist, Lemieux was open not only to America but also to the heritage of French art, whose importance he always upheld; Quebec artists had always looked to the School of Paris as the primary model of modernity in painting. Lemieux often spoke of the Impressionists as the founders of modern art, though he also recognized that Impressionism drew on its predecessors in the best traditions of French painting. In an article published in 1938 he called Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) “the most charming if not the greatest of these painters.” Lemieux considered Renoir the ultimate master of the female nude, and the French artist’s influence is apparent in a charcoal drawing of a nude that Lemieux made in 1942, which is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

Even so, Lemieux was critical of the Impressionists’ superficiality and their reliance on the charm of purely accidental effects created by colour and light. As indicated by the painting The Promenade des Anglais in Nice (La promenade des anglais à Nice), c. 1954–55, he was closer to the Post-Impressionists in spirit, especially Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), of whom he wrote that “his oeuvre consisted of an admirable series of groupings and structures, in forms that were analyzed by a very acute, very refined sensibility.” Lemieux never expressed any definite opinions about the more avant-garde members of the School of Paris, the descendants of the Cubists and the Fauves, preferring, as late as 1938, to say only that “the passage of time will sort the true from the false.” These scruples did not prevent him from subsequently passing judgment on Surrealism, calling it morbid and unhealthy, “symptomatic of a troubled era”; or on abstract art, “a degeneration of Cubism, the affectation of a decadent society.”

One of Lemieux’s deepest beliefs was that a true work of art is emblematic of the historical era in which the artist lives. He recognized this value in the work of his compatriot Alfred Pellan (1906–1988), an avowed follower of the School of Paris. Pellan had lived in Paris since 1926 and knew Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Fernand Léger (1881–1955), and Joan Miró (1893–1983). Lemieux was the first Quebec art critic to review Pellan’s work; in two articles published in 1940, the first in Le Jour in Montreal and the second some months later in Le Temps in Quebec City, Lemieux expressed great admiration for Pellan despite the disparity between his own figurative style and Pellan’s abstract art.

In reply to a flurry of objections that were raised by partisans of an essentially regionalist French-Canadian style of painting, Lemieux defended the universality of Pellan’s work, asking, “Why confine art within these petty boundaries? A great painter represents his time. Whether he portrays his time in scenes of his native land or in still lifes makes little difference, as long as what he expresses on his canvases is dictated by his intelligence and his emotions.”

The Figurative vs. the Abstract

Lemieux’s realm was the figurative, which meant he was out of step as an immense wave of abstraction rolled across North America between 1940 and 1950: the abstract and the nonfigurative became the most compelling areas of exploration in painting for artists who adopted Surrealism and automatic writing techniques, a move which led to geometric formalism and optical art. During these decades and the years that followed, Lemieux remained faithful to the figurative, as exquisitely demonstrated in Mid-Lent Festival (Les mi-carêmes),1962, which depicts a mid-Lent festival whose participants seem to have come straight out of the commedia dell’arte, although he was by no means unaware of the excitement swirling all around him.

Lemieux was one of the first critics to define the word “abstraction” in the French-Canadian press. He conceived abstract art as the sophisticated expression of a society in decline. In his eyes, the work of his contemporaries illustrated the stressed, mechanistic quality of the time they were living through and the frightening future it portended. “An anxious era will not produce tranquil art. Painting today is in transition. It is tormented, disturbed, and seeking, like contemporary humanity, new modes of expression.”

However, his reaction to the work of his contemporaries was disappointment and bitterness, and his desire for independence only grew stronger throughout his career. He had worked for an opening up of art toward the universal, and for liberation from the rigidity of academicism, but, as he explained, “The liberation I welcomed with so much enthusiasm very quickly turned into the worst kind of slavery. In the heyday of Père Couturier, it seemed everyone was more royalist than the king. Figurative painting was tolerated, but with strict reservations: it had to look like [Pierre] Bonnard, [Chaïm] Soutine or [Georges] Rouault. Within the space of a few years, I could even say a few months, we had our Fauves, our Surrealists, our Abstractionists, and our Expressionists. Never before was there a time of such servile imitativeness in our art.”

Lemieux never spoke publicly about the painting of Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), or the Refus global manifesto of 1948. If his silence left anyone in doubt about his opinion of the Automatistes and their revolution, his position became quite clear in 1954 on the occasion of an exhibition called La matière chante at the Galerie Antoine in Montreal. Lemieux, alias Paul Blouyn, and his student Edmund Alleyn (1931–2004) created a controversy by submitting, as a prank, some nonfigurative works they had painted using “the automatist method.” Their work was accepted for the exhibition by Borduas, who had come from New York specifically to select the paintings that were to be hung. The hoax deepened the rivalry between Quebec City and Montreal, which at that time were briefly on opposite sides in the question of figurative versus abstract art.

Space and Time

This artistic and critical rivalry in Quebec in the mid-1950s was happening just when Lemieux’s painting was undergoing a transformation. With works such as The Evening Visitor (Le visiteur du soir), 1956, and Julie and the Universe (Julie et l’univers), 1965, he turned away from narrative to concentrate on the flat space of the picture plane, maximizing its suggestive power with balanced and radically simplified combinations of form and colour. He looked deep into his past to find again the happiness of childhood; he exalted nature in pure, horizontal compositions; and he expressed the perilous human condition by showing figures isolated in their personal solitude.

The critic and medical doctor Paul Dumas (1928–2005), rather than marginalizing these works of Lemieux’s classic period (1956–1970) by simply emphasizing their opposition to the prevailing nonfigurative style of the time, explains that Lemieux’s “daring arrangements on the canvas, his rigorous composition, the subtlety of colour and accuracy of tones, his poetic intensity and the contained emotion, so powerfully conveyed, establish his work on a level of equality with the most prestigious nonfigurative art.” The artist himself did not go quite that far in finding a resemblance. He commented, “Certainly, colour or line can sometimes create a specific emotion without necessarily defining a subject. But it’s also clear that when identifiable subjects are abandoned, painting has a tendency to lose its way and fall into decorativism. From there it’s just one small step to being nothing but technique. There has to be mystery in a painting.”

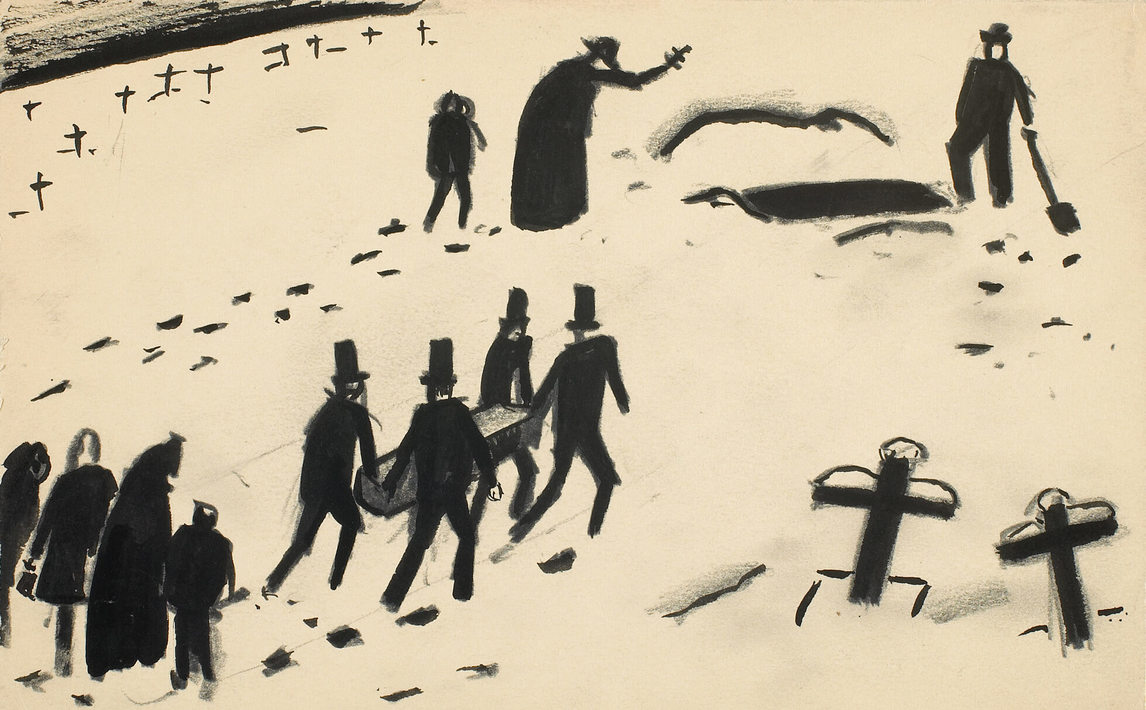

Space and time—past, present, and future—fundamentally preoccupied Lemieux throughout his long career and this is reflected in early notebook drawings and sketches, such as Funeral, c. 1916–28, and Melancholy, 1938. “I’m haunted most of all by the dimension of time! Space and time! Time flowing; man within space, watching time flow away.” Self-portrait (Autoportrait), painted in 1974, is charged with meaning, constructed as a mise en abîme showing the stages of his life as a man and an artist. Lemieux’s late Expressionist period (1970–1990) would be dominated by great universal themes: the destructive power of war, the threatening modern city, and humanity’s obsession with death.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements