Lazarus 1941

Jean Paul Lemieux, Lazarus (Lazare), 1941

Oil on Masonite, 101 x 83.5 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Lazarus is among the most fully achieved statements of Jean Paul Lemieux’s primitivist period (1940–1946). This narrative work develops in four scenes linked by a road that snakes through the composition. The viewer’s eye is first arrested by the church, from which the artist has removed both the roof and the apse. The view from high above allows us to look down on the priest preaching to a more or less attentive congregation. Lemieux’s penchant for humorous touches can be seen in details like the parishioner who has fallen asleep with his head against a pillar and the two men having a casual chat in the choir loft.

Outside the church we find three more scenes. In the lower right of the composition a funeral procession makes its way toward the cemetery, where Jesus, dressed in a business suit, blesses Lazarus, who has just risen from the dead. On the left there is a scene of war: six bomber aircraft are flying above the ruins, while villagers and parachutists landing on the ground are killing each other. In the distance, a schooner sails toward the catastrophe under a blue sky enlivened by puffy clouds.

Lemieux’s subject is the tranquil existence of a small French-Canadian community that listens to the comforting words of its priest about the miraculous resurrection of Lazarus, while the war rages far away in Europe. At first glance, this narrative picture might seem to belong to the category of folk art. That was the opinion of Lemieux’s friend the ethnologist Marius Barbeau (1883–1969), who saw its imagery as primitive and folkloric.

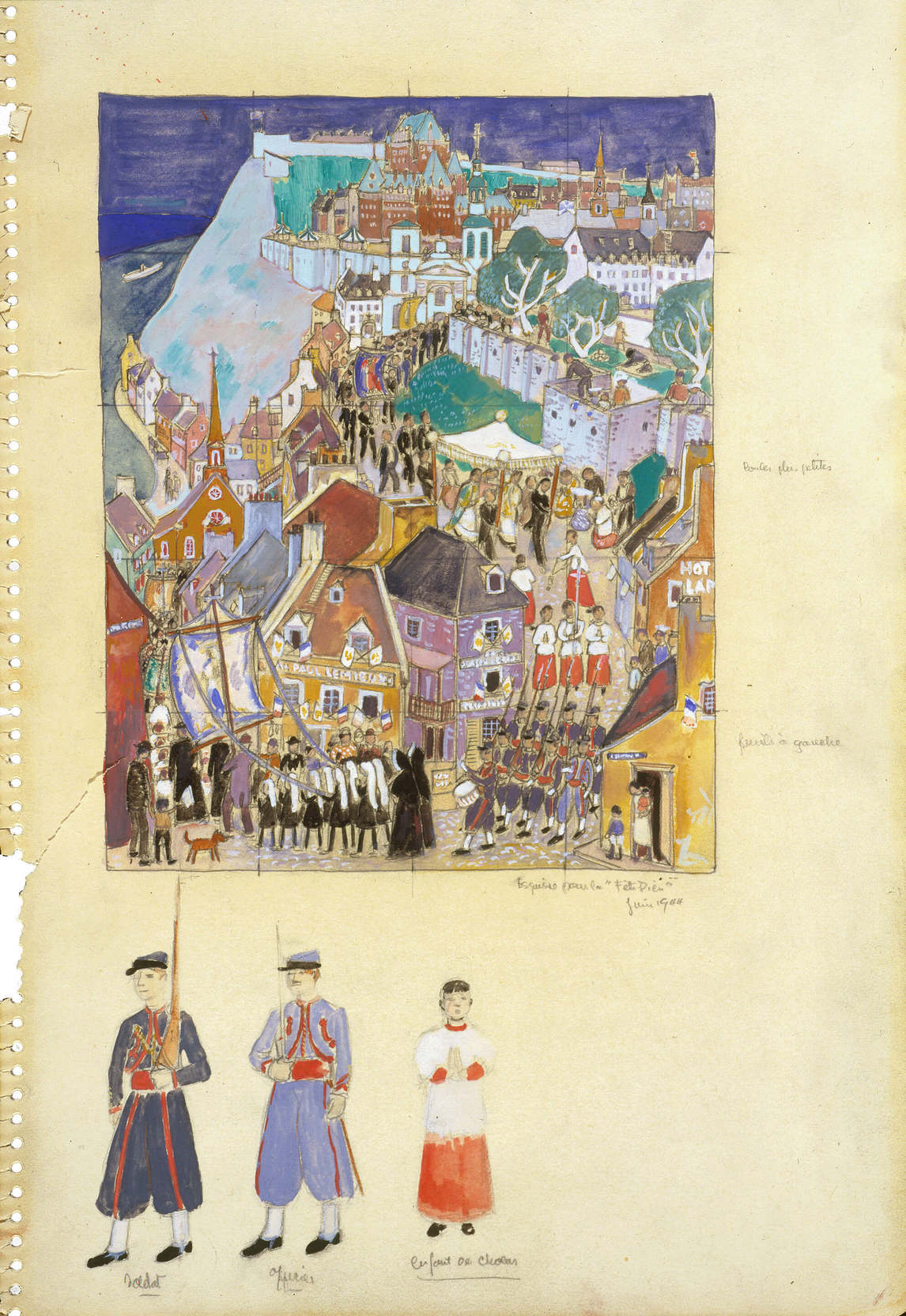

However, Lazarus is a complex work by a remarkably sophisticated artist. On the one hand, the synthetism of the views of the church and the modern staging of the resurrection of Lazarus have echoes of the French Pont-Aven School, also called the Nabis, whose influence inspired the renewal of decorative religious art in Quebec from the 1930s to the 1960s. This work by Lemieux belongs with these movements, demonstrating that superficial religious practice cannot nourish an authentic spiritual life. On the other hand, as in Corpus Christi, Quebec City (La Fête-Dieu à Québec), 1944, the painter is using cavalier perspective (also called oblique projection), which was practised at Sienna and Florence by the painters of the Quattrocento and reappeared later in the still lifes of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). This type of perspective from above creates a narrative space by providing a view on different levels, with minimal overlapping.

Along with these European influences, Lazarus owes a debt to the social realism of the Ashcan School, which Lemieux learned of in the United States at the beginning of the 1930s. Several aspects of the painting make reference to the school, including the use of caricature and irony, but what viewers mostly remember is the condemnation implied by the juxtaposition of the scenes of war and the preaching of the sermon. These two scenes place drama and detachment in stark contrast: the bombs dropping on a civilian population and the oblivious, untroubled life of a people subjected to the power of the Church.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements