Jean Paul Lemieux (1904–1990), painter, illustrator, critic, and teacher, is one of the most significant artists in the history of Canadian modernity. While Lemieux evolved on the margins of the principal art movements of his time, his oeuvre belongs with the great figurative exploration of the twentieth century. Born in Quebec City, he chose to pursue his artistic and teaching career in his native city. His art and his thought radiated outward from that centre for more than half a century.

Childhood and Youth

Jean Paul Lemieux was born on November 18, 1904. His father, Joseph Flavien, an agent with Greenshields Ltd., a large supplier of wholesale merchandise, was often absent because his work required him to travel. His business was next door to the family residence at 68 rue Saint-Joseph, where Joseph Flavien’s wife, Corinne Blouin, Jean Paul, and his older sister, Marguerite, lived with an elderly aunt and a domestic servant. In 1908, after the birth of a new baby, Henri, the family moved to a luxurious Victorian-style greystone house at 128 Grande Allée Est in the city’s Upper Town.

Growing up in both English- and French-speaking milieus, Jean Paul had all the advantages of a privileged childhood. Winters were spent in Quebec City, but from May to November the family stayed at the Kent House hotel (now the Manoir Montmorency), a summer resort about twelve kilometres outside the city, overlooking the spectacular Montmorency Falls. Lemieux looked back on his early childhood as the “age of perfect happiness” and depicted his time there in 1910 Remembered, 1962, and Summer of 1914 (L’été de 1914), 1965.

When Lemieux was ten years old, he met an American artist who was painting pictures at the Kent House for the restoration of one of the hotel lodges. “His name was Parnell,” Lemieux would later recall. “I got into the habit of going to watch him work, and I saw him paint some very big canvases. I was fascinated. That was when I began to make sketches.” Nothing more is known of Parnell or his career, but his passage through Jean Paul’s life in 1914 had a profound effect on the young boy’s destiny. That summer, inspired by the extraordinary view of the waterfall, Jean Paul painted his first watercolour.

In autumn 1916 Corinne and the children left Quebec City. Marguerite suffered from chronic rheumatism and her doctors recommended the climate of California. In Berkeley, Jean Paul and Henri continued their schooling in English, and the family went on trips to San Francisco and Los Angeles. Jean Paul was taken to visit movie studios in Hollywood and acquired an interest in cinema. Marguerite settled permanently in California, where she married in 1919.

Education: The Montreal Years

In 1917 the Lemieux family moved to Montreal. There Jean Paul went to the Collège Mont-Saint-Louis, then Loyola College. During this period he took lessons in watercolours and, in 1926, began studies with the respected Canadian Impressionist painter Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937). Suzor-Coté taught a class in a studio he occupied in the home of sculptor Alfred Laliberté (1878–1953). Several other artists had studio spaces there, including Maurice Cullen (1866–1934), Robert Pilot (1898–1967), and Edwin Holgate (1892–1977), painters who made a living from their art, exhibited regularly, and belonged to the Arts Club of Montreal.

In September 1926 Lemieux enrolled at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal in order to become a professional painter. The basis of the curriculum was drawing, “the single indispensable key to the fine arts.” Lemieux never minded the long, laborious sessions of copying antiquities and ornaments. His respect for the importance of drawing never diminished, and he loved to repeat Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s (1780–1867) famous remark: “I’ll put a sign on the door of my studio: ‘Here we teach drawing, and create painters.’”

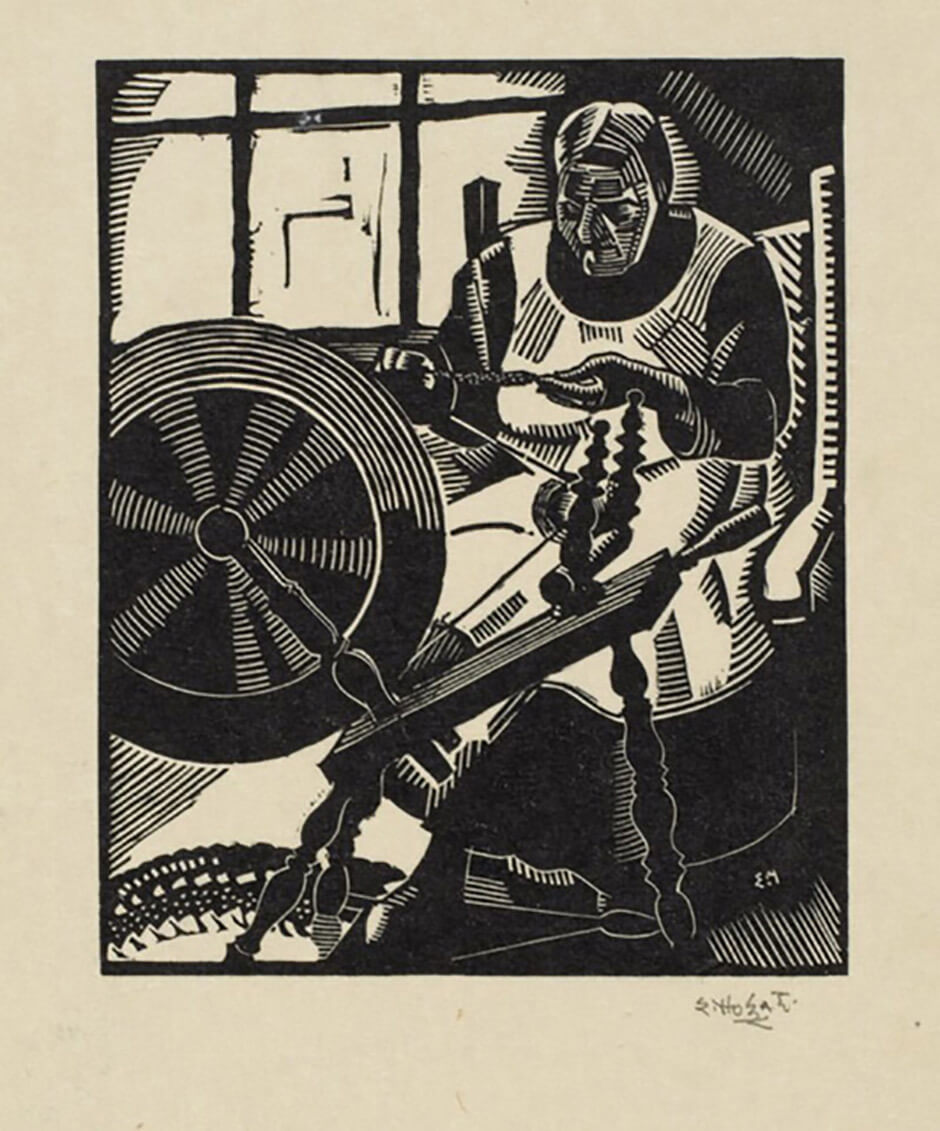

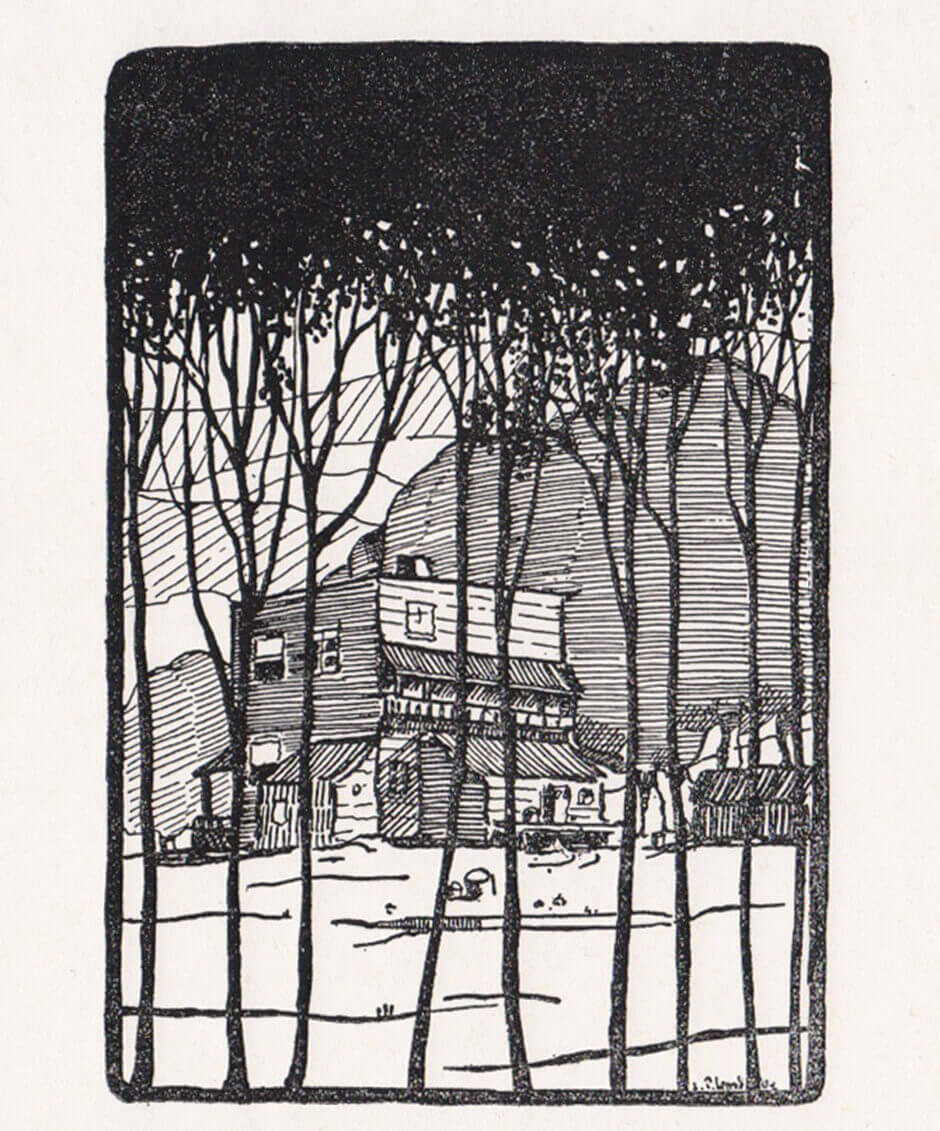

At the École des beaux-arts in Montreal there was absolutely no tolerance for modern art. As the director, Emmanuel Fougerat, stated, “You won’t see a single ‘Fauve,’ nor the smallest ‘Cubist’ or ‘Dadaist’—not one of those lazy slackers.” At the time of Lemieux’s arrival, Fougerat left the school and was replaced by Charles Maillard, who maintained his predecessor’s policy for the next two decades. Having felt constrained within the very conservative environment of the school, Lemieux had good memories of just one of his teachers, Edwin Holgate, his instructor in engraving, who was recognized at that time as one of the best draftsmen in Montreal. Holgate was part of the resurgence of wood engraving in Canada, and was at the height of his career as an illustrator. His influence can be seen in the careful attention to architectural detail in the illustrations Lemieux created for two novels, La pension Leblanc by Robert Choquette (1927) and Le manoir hanté by Régis Roy (1928).

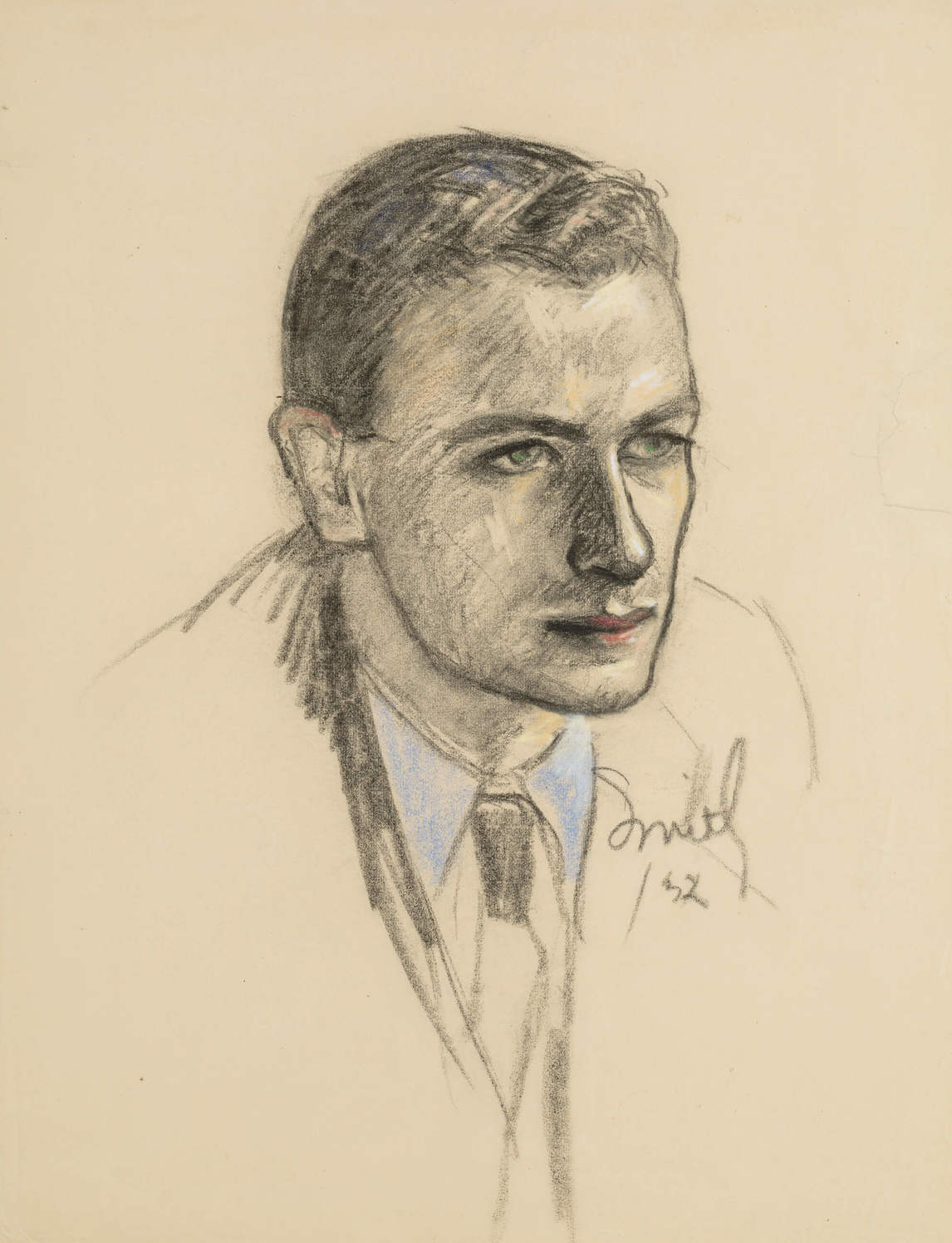

At the École, Lemieux met Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), developed a camaraderie with Jean-Charles Faucher (1907–1995), and Louis Muhlstock (1904–2001), and established long-lasting friendships with the painters Francesco Iacurto (1908–2001), Jean Palardy (1905–1991), and Jori Smith (1907–2005), and the poet Hector de Saint-Denys Garneau (1912–1943). With the exception of Borduas, whose art would be committed to the nonfigurative and the abstract, most of Lemieux’s fellow students were involved in the renewal of figurative art that flourished in Quebec in the 1930s and 1940s.

In the dark days of October 1929 when the world economy crashed and the Great Depression began, Lemieux and his mother were in Paris, staying in Montparnasse, after travelling from London to Spain and then France. The surrealist frenzy that was inflaming the creative minds of Europe did not touch Lemieux. Nor did he pay much attention to Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), or Henri Matisse (1869–1954)—artists he would later defend in his critical writings—all of whom had been excluded from the curriculum at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal. However, he did meet with fellow French-Canadian artist Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942), a painter well known for his landscapes of the Charlevoix region who was then working on the illustrations for an edition of Louis Hémon’s novel Maria Chapdelaine.

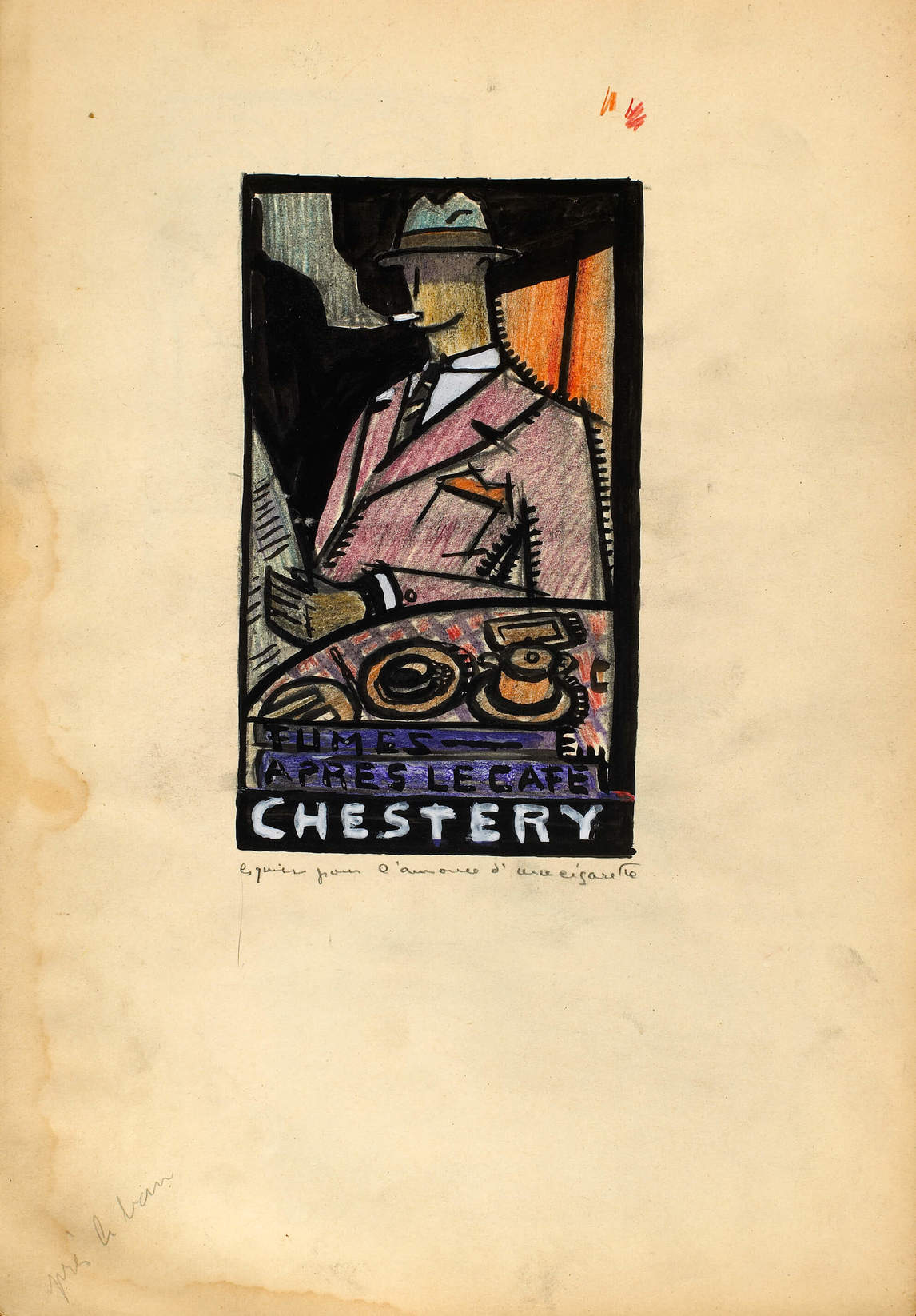

On this two-month visit to Paris Lemieux was chiefly interested in recent developments in illustration. He studied advertising art, and took life drawing classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and Académie Colarossi. By the end of his stay he thought he had a better idea of the life he wanted to make for himself in the world of art. Back in Montreal he and his friends Jean Palardy and Jori Smith set up a commercial and advertising art company, which they called JANSS, an acronym based on the names of the three artists. But the economic crisis caught up with them and the company closed its doors six months later.

After this setback Lemieux took some time off from all activities to think things over. He went to California to stay with his sister, Marguerite, for a while, and on the way back visited museums and galleries in Chicago and New York. Upon seeing Gauguin’s works in Boston, he was struck by the extraordinary symbolic power of art, an awareness that would become the cornerstone of the works of his classic period (1956–1970). In addition, American Social Realism interested him, as did the Ashcan School, with its descriptive studies of the contemporary city and the daily lives of ordinary people. He was impressed by the Works Progress Administration, which had generated a vast movement of muralist art in the United States.

Encouraged by his European and American discoveries, Lemieux returned to his studies at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal in 1931; he would graduate in 1934. In the evenings he often took part in the studio sessions that Edwin Holgate offered to his students and interested friends who wanted to practise the art of drawing the nude model. Others in attendance were Borduas, Stanley Cosgrove (1911–2002), Saint-Denys Garneau, and Jori Smith. Lemieux also met Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974) there; he found the discussions between Holgate and Roberts particularly stimulating, the latter having, in 1927–28, studied at the Art Students League of New York under the tutelage of John Sloan (1871–1951), a realist landscape artist of the Ashcan School.

Teaching

Newly graduated in 1934, Lemieux was hired as an assistant teacher of drawing and design at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, his alma mater. The following year he moved to the recently founded École du meuble, where the director, Jean-Marie Gauvreau (1903–1970), hoped to create a synthesis of culture, technology, and the decorative arts. In this free atmosphere, Lemieux taught painting and perspective drawing. Among his colleagues were Maurice Gagnon (1904–1956), professor of art history, and the architect Marcel Parizeau (1898–1945), who opened Lemieux’s eyes to the great modernist painters of the School of Paris.

Lemieux accepted a teaching position at the École des beaux-arts de Québec, in Quebec City, in 1937, and in June of that same year married Madeleine Des Rosiers, an artist he had met as a student at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal. On his return to Quebec City he had three careers on the go at the same time: painter, teacher, and art critic.

At the Montmorency Gallery in Quebec City the following year, he and Madeleine had a joint exhibition, which was favourably received by the critics, and the Musée de la province de Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) bought one painting from each artist. Despite her success, Madeleine at this point gave up painting to devote herself to her husband’s career. Their only child, Anne Sophie, would be born in 1945.

In September 1940 the couple moved out of the city to an old stone house on the cliff top at Courville, which Lemieux recorded in his painting Portrait of the Artist at Beauport-Est (Portrait de l’artiste à Beauport-Est), 1943. Surrounded by gardens, the house was overflowing with antique furniture and other interesting objects that Jean Paul and Madeleine had brought back home after vacations in the Charlevoix region, where they were often accompanied by their friends Jean Palardy (1905–1991) and Jori Smith (1907–2005). Jean Paul and Madeleine were invested in the movement to preserve Quebec’s cultural heritage, a movement led by art historian Gérard Morisset (1898–1970) and the ethnologist Marius Barbeau (1883–1969), who would become lifelong friends of theirs.

In Lemieux’s classes, the atmosphere was always one of trust and freedom. He was open to the art of the past as well as to contemporary art. He conceived his role as a teacher to be that of a guide who does not impose a method, but rather helps his students to find the path of their own talent. “I have never believed that you can show someone how to paint. You can teach the rudiments, the techniques, the tricks of the trade, but you can’t teach painting.” Several of his students, including Edmund Alleyn (1931–2004), Michèle Drouin (b. 1933), Benoît East (b. 1915), Marcelle Ferron (1924–2001), and Claude Picher (1927–1998), went on to have successful careers in Quebec and internationally.

Outside the classroom, Lemieux readily shared with his students his passion for and extensive knowledge of traditional Québecois art, captivating them during visits to churches on the Beaupré Coast and Île d’Orléans.

In 1965 Jean Paul Lemieux retired from the École des beaux-arts de Québec. He was sixty-one years old, and from now on he would dedicate himself entirely to his art.

Art Criticism

In 1935 Lemieux embarked on a career as an art critic. For the next ten years he was actively engaged in writing in both French and English for journals and newspapers, including Le Jour, Regards, Maritime Art, and Canadian Art. In a tone that was measured, though combative and sometimes polemical, he set out his thoughts on the transition to modernity in art and what it would require: a broad knowledge of Western art, openness to contemporary trends in Europe and the United States, the democratization of art, and so on.

Although he was the first to comment on abstraction in the French-Canadian press, Lemieux did not wholeheartedly embrace the practice of abstraction, which he perceived as “a degeneration of Cubism, combining colour for the sake of colour with form for the sake of form, with no care for the subject that was treated.” Indeed, throughout his career as a painter, Lemieux would never turn to abstraction.

In critical texts published in 1938 Lemieux defended the democratization of art. He hoped to see the establishment of a muralist movement in Canada that placed fine art in public spaces similar to the one initiated in the United States during the Depression. In his own first planned mural, “Québec (projet de peinture murale),” which was never realized, he envisioned a vast horizontal panorama of Quebec City, with the city dominated by the snowy peak of Cap Diamant and an accurate rendering of the neighbourhoods below, their architectural forms swarming with life, protected by the river, while the Upper Town was secure within its fortifications.

Early Success

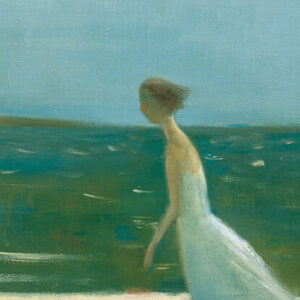

After his return from the United States in 1931, Lemieux began to show work in the annual Spring Exhibition held by the Art Association of Montreal. In 1934 he won the William Brymner Prize, an award for artists under the age of thirty. Though the piece that won the prize, House at Éboulements (Maison aux Éboulements), c. 1934, is now lost, Seascape, Bay St. Paul (Marine, Baie St. Paul), 1935, is painted in the same style that the honoured work would have been. In that same year he began his frequent participation in the annual exhibitions of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

Also in 1934 the Musée de la province de Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec), which had just opened its doors the year before, purchased its first painting by Lemieux, Afternoon Sunlight (Soleil d’après-midi), 1933. It was his first sale to an institution. Over the years, the museum acquired many major paintings by the artist, as well as drawings and illustrated books.

During his years in Montreal, from 1931 to 1937, Lemieux produced mostly portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes. His work was influenced by the landscape aesthetic of the Group of Seven and by the regionalist principles of American Social Realism; from Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) he assimilated a rigorous approach, and from Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), the use of symbolism. He discussed these influences in his writing, and they can be seen in his paintings of the time; Those Beautiful Days (Les beaux jours), 1937, provides a good example.

As the 1940s began and Canadian painting moved farther away from the figurative, for example, with the works of Fritz Brandtner (1896–1969), David Milne (1882–1953), and Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) and his fellow Automatistes, Lemieux reacted by going in the opposite direction, creating works that were more narrative than ever. In what is known as his primitivist period (1940–1946), his art borrowed from the Italian primitives and from naïve art. Several large compositions combining religious and secular content date from this period, notably The Disciples of Emmaus (Les disciples d’Emmaüs), 1940; Lazarus (Lazare), 1941; Our Lady Protecting Quebec City (Notre-Dame protégeant Québec), 1941; and Corpus Christi, Quebec City (Fête-Dieu à Québec), 1944. Lemieux’s sense of humour could often be perceived as biting, and many of these works are imbued with his mischievous character. In Lazarus, one of the parishioners is dozing off during the sermon, while in Corpus Christi, Quebec City, a little boy is seen urinating against a tree.

By the mid-1940s Lemieux was considered an artist in the first rank of young Canadian painters. He was not a member of Montreal’s Contemporary Arts Society but was nonetheless invited by the society’s founder, John Lyman (1886–1967), to take part in its exhibition Art of Our Day in 1940. The work Lemieux showed, The Disciples of Emmaus, was then selected by Marius Barbeau (1883–1969) for his book Painters of Quebec.

In 1942 The Village Meeting (L’assemblée), a work he had created in 1936, was chosen for Aspects of Contemporary Painting in Canada, an exhibition that toured nine American cities. In 1944, the same work was included in Canadian Art, 1760–1943, an exhibition held at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut. The following year, Lazarus, 1942, was part of the first exhibition organized by UNESCO, showcasing work from twenty-six countries at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris. From this point on, Lemieux’s art would be known beyond the North American continent.

A Critical Eye on His Contemporaries

Lemieux closely followed the great debate about modernism, centred on Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) and Alfred Pellan (1906–1988), who with their respective manifestos, Refus global and Prisme d’yeux, polarized the art scene in the late 1940s. Lemieux’s view, however, was that he was a victim of this avant-gardism. “I no longer dared to paint. I was afraid of appearing reactionary,” he admitted. “The liberation I welcomed with so much enthusiasm very quickly turned into slavery of the worst kind…. Figurative painting was tolerated, but with strict reservations…”

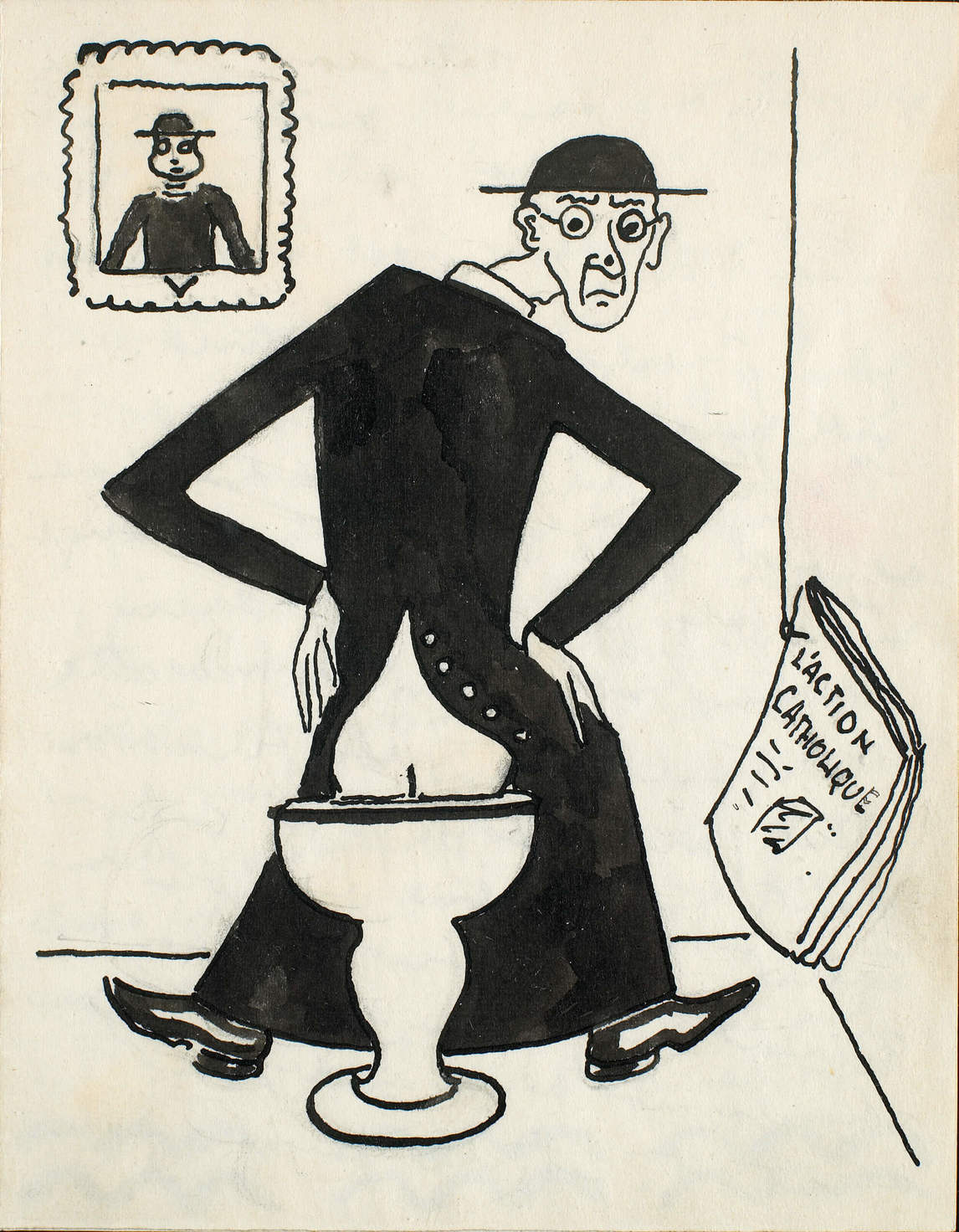

It was long presumed that between 1947 and 1951 Lemieux practically ceased to paint. However, though less is known about this period, and it was a time for Lemieux of intense self-reflection about his artistic practice, he nevertheless produced studio works as well as loosely sketched oils of the Charlevoix landscape. The studio works often consisted of humorous scenes and compositions reflecting Lemieux’s quest for a simpler pictorial language.

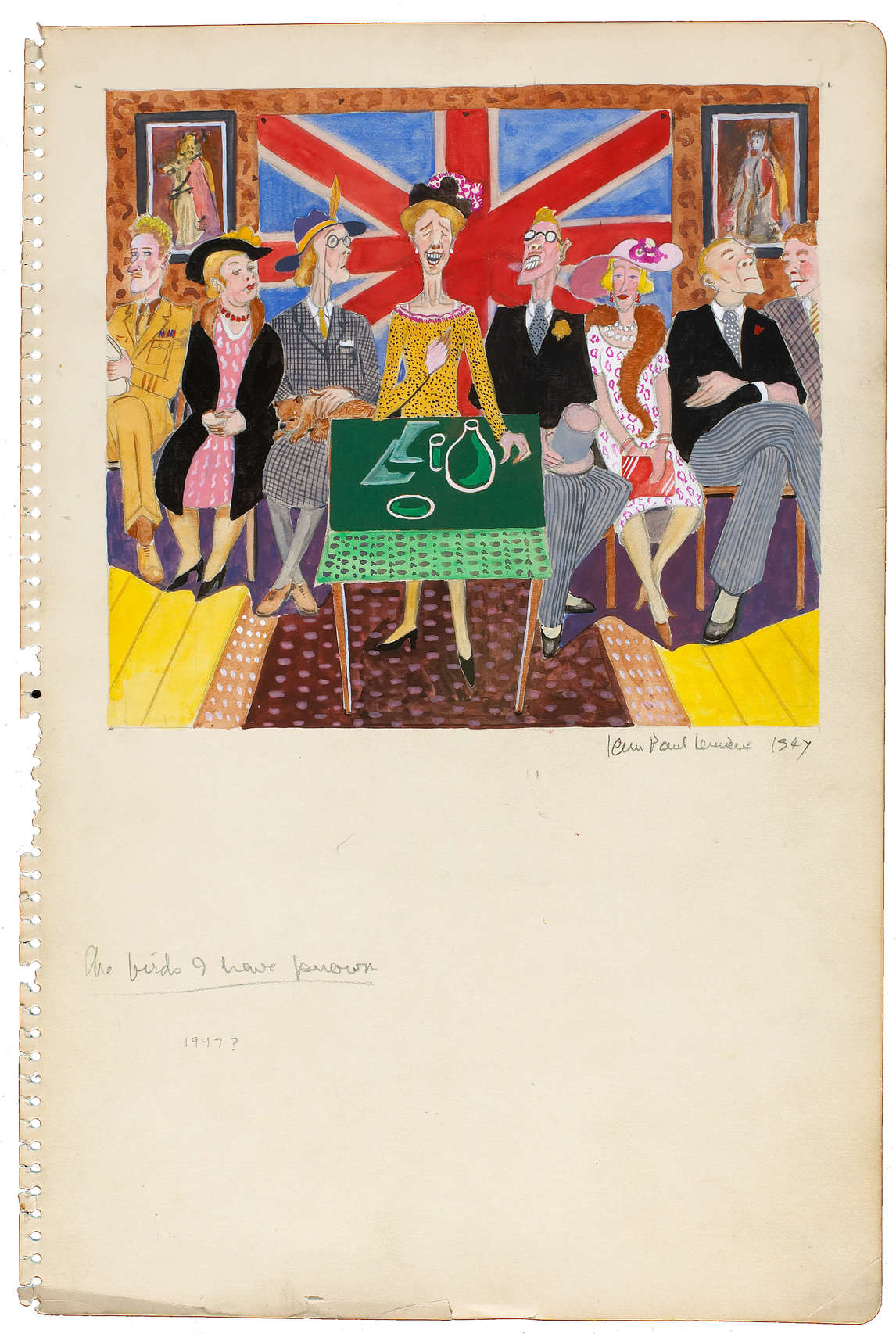

As a champion of modernity Lemieux reacted against the moral rigidity and self-righteousness of his time, and protested the glorification of rural life promoted by the conservative ideology of the Duplessis era. In his social-realist vein he did not hesitate to satirize bourgeois anglophone society, then in a position of authority in Quebec, as witnessed in his The Birds I Have Known/Les drôles d’oiseaux que j’ai connus, 1947, a caricature worthy of Honoré Daumier (1808–1879).

Recognition and Fame

In the summer of 1951 Lemieux did return to work, zealously but slowly, allowing himself from six months to a year off between paintings. “Art is like a labyrinth,” he explained many years later. “One must search long and ardently for the passage that leads to the light.” He was referring, among other works, to his painting The Ursuline Nuns (Les Ursulines), 1951, which in 1952 won first prize at the Concours artistique de la province de Québec.

In 1954 he received a grant from the Royal Society of Canada that allowed him to take a trip to France with his family. This European sojourn resulted in a major change in his pictorial language. “I was absolutely lost in France,” he said later. “Everything I tried to paint in Paris looked like Monet or Bonnard. In the south of France it was Matisse or Cézanne. When I got back to Canada I began to paint in a completely different manner.” The Far West (Le Far West), 1955, is a prelude to his classic period, which would last from 1956 to 1970. It is characterized by a horizontal format, bare subject matter, and simplified pictorial space; the “synthetist” art of the Nabis, inspired by Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and by the proto-Cubism of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), formed the basis of his new aesthetic identity.

The Evening Visitor (Le visiteur du soir) and The Noon Train (Le train de midi), both from 1956, are emblematic of this new language that ushered in Lemieux’s classic period. The vast spaces that began to appear on the surface of his canvases grew from a strange sensation he had experienced the same year on the train between Quebec City and Montreal. “I had the feeling of moving closer and closer to something, but something that was ungraspable, elusive; it escaped me. That was the impression that I attempted to convey.”

With this breakthrough in his work, which reflected Lemieux’s profound identification with the North, he began to reach a new and much larger audience. Between 1958 and 1965 he had solo shows in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, and Quebec City. He took part in four biennial exhibitions organized by the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. His international reputation was growing, as his works were shown at the Bienal of São Paulo, the Canadian pavilion at the Brussels International Exposition, the Pittsburgh International Exposition, and the Venice Biennale, in addition to exhibitions of Canadian painting in Warsaw, at MoMA in New York, at the Tate Gallery in London, and at the Musée Galliera in Paris.

As a painter whose work was highly personal yet iconic, figurative yet modern, Lemieux’s reputation was now firmly established. There was a consensus among critics regarding the importance and value of his work, and the honours began to pile up. In 1966 Lemieux was received as a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. In Canada’s centennial year, 1967, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts mounted a retrospective of his work, which toured to the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) and the National Gallery of Canada. In that same year he received the Canada Council Medal, and in 1968 he became a Companion of the Order of Canada.

The Final Twenty Years

During the 1970s and 1980s, Jean Paul Lemieux’s painting underwent another transformation. As Lemieux was growing older (a preoccupation illustrated in his self-portrait of 1974), the serenity and nostalgia of his classic period (1956–1970) gave way to a new, tragic Expressionist period (1970–1990), with works reminiscent of Edvard Munch (1863–1944), whose famous The Scream, 1893, had been heard at the end of the previous century.

Heralding this change, works like The Aftermath/La ville détruite, 1968, communicated his existential distress about the future of humanity, and he illustrated these fears in the apocalyptic scenes in his notebook of drawings titled Year 2082, 1972. His pessimism is clear in Dies Irae, 1982–83, and Anguish (Angoisse), 1988, evokes war or the threat of nuclear conflict. In this late work, Lemieux did not please the public; although the paintings were shown in Quebec City, Montreal, and Trois-Rivières, they did not sell, and the critics ignored them.

In the 1970s Lemieux also returned to illustration, an early love from his student years. In 1971 he illustrated Gabrielle Roy’s La petite poule d’eau. The novelist was a close friend; she too spent summers at Charlevoix. Lemieux had painted her portrait in 1953. In 1981, ten years after illustrating Roy’s book, he created illustrations for Louis Hémon’s Maria Chapdelaine. Finally, in 1984–85, he paid homage to his country by illustrating the book Canada-Canada, a collection of writings on each province and territory by prominent Canadian authors.

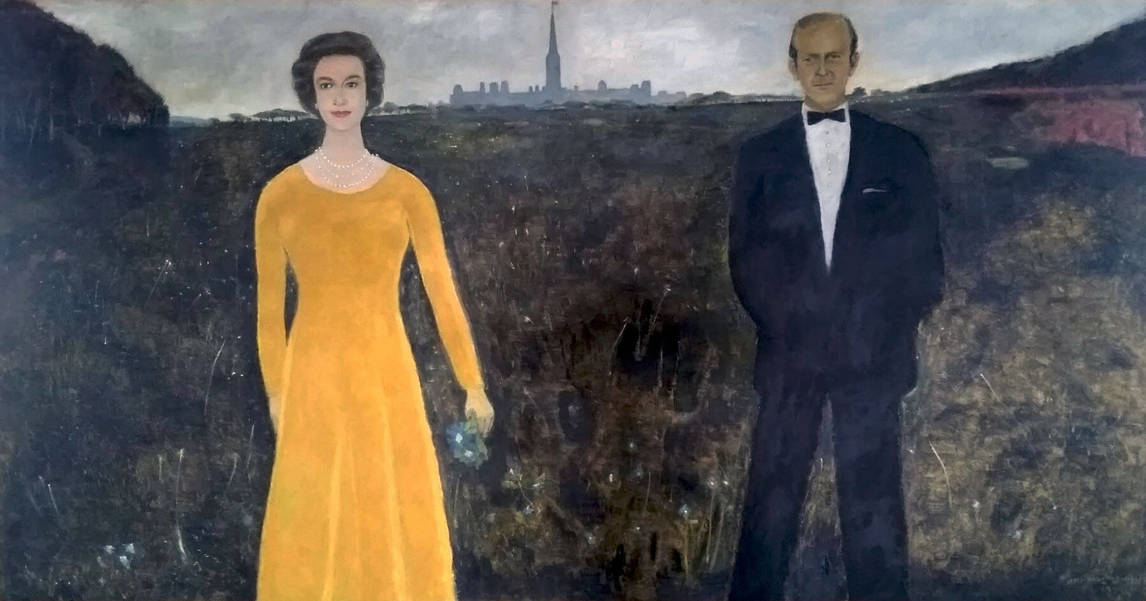

Lemieux was an established artist in the political world as well. In 1967 he painted a mural in the Charlottetown Confederation Centre (now the Confederation Centre for the Arts), representing the Fathers of Confederation. In 1977 he created the official portrait of the then Governor General of Canada, Jules Léger, and his wife. Two years later he caused an uproar with his very informal portrait of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip.

Jean Paul Lemieux died in Quebec City in 1990, two years before the retrospective honouring him at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. The catalogue, written by the curator of the exhibition, the art historian Marie Carani, was an enormous, definitive study, situating Lemieux’s work in the context not only of Quebec and Canada but also within the great adventure of figurative art in the twentieth century.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements