Chambers constantly experimented with techniques. He was trained in the traditional methods and motifs of drawing and painting in Spain yet forged his own type of art in both film and painting. He called it perceptual realism.

Classical Training in Europe

The range of artistic techniques that Jack Chambers learned and practised adds to the paradoxical tension that ran through his life, both as an artist and as a family man. As an artist, he was a “radical classicist,” both a perfectionist and an inveterate experimenter. The foundations of his masterly abilities as a draftsman and painter were laid during five years of study at the highly traditional Escuela Central de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. His drawings at this time tended toward detail, and his paintings were tightly controlled. He became expert in depicting both the human figure and landscape. Many of his paintings from Spain are dark in mood and lean toward a surrealistic juxtaposition of forms (for example, Man and Dog, 1959).

Experimentation in London

After his return to Canada in 1961, Chambers became aware of both European and American art after Cubism. He experimented with paint application and vibrant colour in works such as McGilvary County, 1962, and The Unravished Bride, 1961. Chambers later writes:

At some time in 1961, I became aware of de Kooning and Pollock and Klee and Kandinsky. I had never seen their works before and that included whatever had happened in painting since Juan Gris and Picasso. I began to texturize the surfaces of my panels with a mixture of rabbit glue and marble dust. Once dry, I could adjust the topography with sandpaper. These surfaces were covered with gesso and then I spilled various colours of house enamels on the gesso surface and sprinkled it with turps to get it running. I then tilted the board this way and that till some interesting effects appeared, and then I laid it flat and let it dry or added more paint and turps.

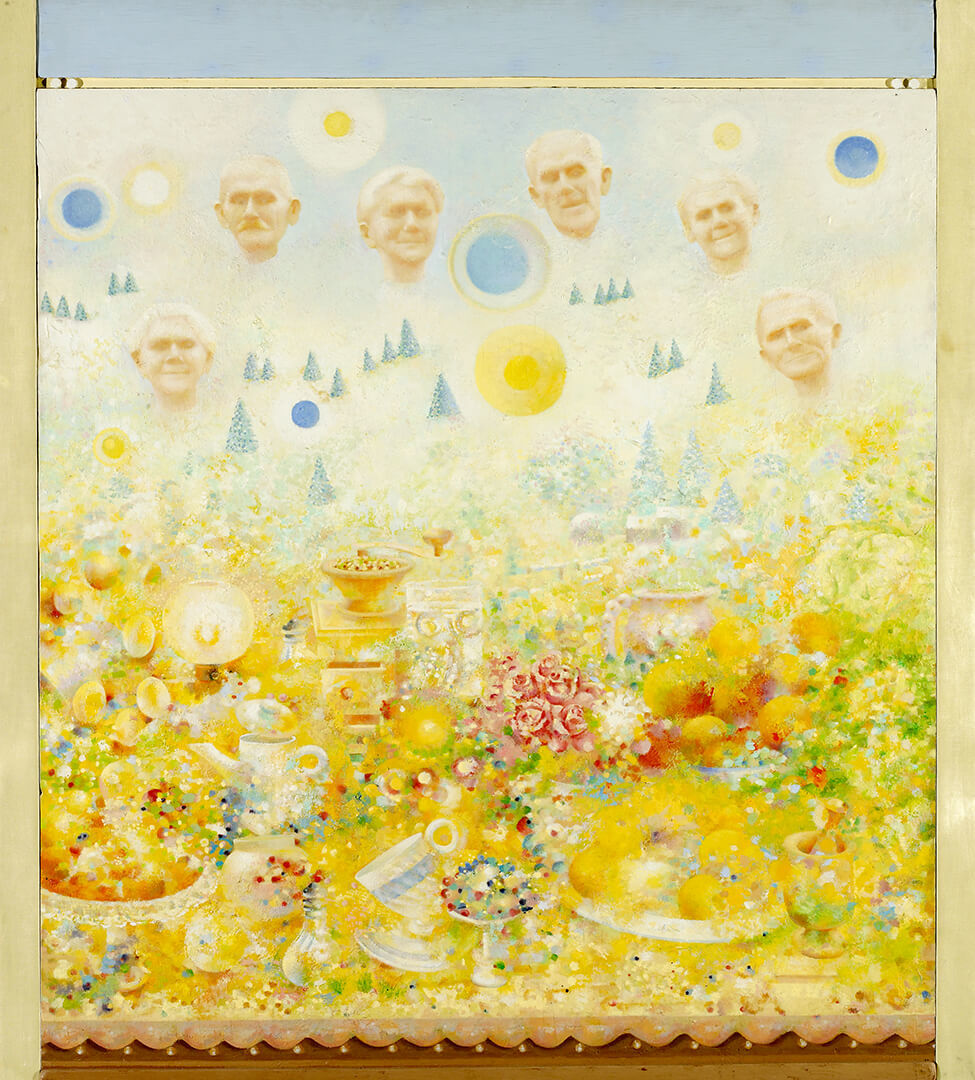

The look of his paintings changed again in the mid-1960s. In works such as Antonio and Miguel in the USA, 1964, and Olga and Mary Visiting, 1964–65, we can note three innovations. As in his paintings from 1961–62, the frames are carefully constructed and painted to become full parts of the overall image; colour is subdued, and forms appear as if through an opaque wash, unifying but also clouding the entire painted surface; and most radically, forms are fragmented in an attempt to add a sense of temporal movement to the images. Chambers described this aspect of Olga and Mary Visiting in terms that underline his concomitant interest in film: “A painting gets put together just like an experience—in particles. [This work] isn’t the description of a visual moment; it’s the accumulation of experienced interiors brought into focus.”

“Personal” Films

Chambers began to experiment with filmmaking in the early 1960s and called the result “personal” films. This medium offered freedom from the strictures of painting and the demands of European high culture that he admired and internalized in Spain. By 1964 he had prepared storyboards and was inquiring about distribution for the film later known as Mosaic, completed in 1966. Fellow artist Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) reported that Chambers began the film with a borrowed 16mm Cine Kodak camera and soon bought a Bolex camera. Other records suggest that he bought the Bolex in 1966. To edit his films, he seems to have used a Zeiss Moviscop, which could not handle sound. Chambers consulted sound engineers in London and Toronto for his non-descriptive soundtracks.

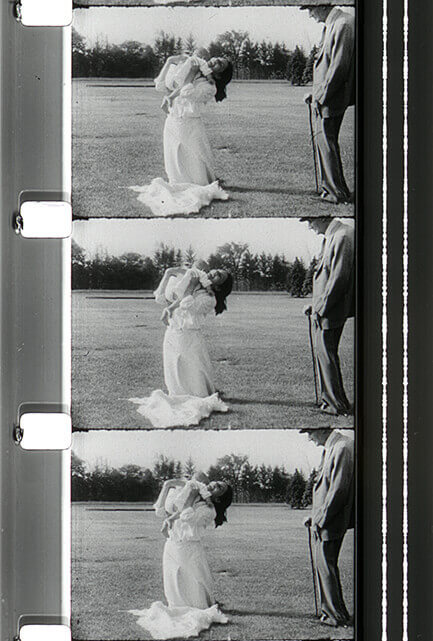

Chambers made ten to twelve films (completed, planned, lost, or incomplete). Mosaic is a 9-minute black and white 16mm film with sound. The film is a non-linear montage of images as disparate as those of Olga Chambers, a doctor’s waiting room, bus and car rides in London, and a dead raccoon, evoking the themes of motherhood, place, and death. In subsequent films—especially The Hart of London, 1968–70, on which Chambers’s sterling reputation as an avant-gardist largely rests internationally—he increasingly combined found film footage with his own and experimented with techniques such as solarization and reversing the direction of the film overlays. Colour figures prominently in many of Chambers’s films. He also used many still photographs, either his own or others’ (for example, Hybrid, 1967). After his leukemia diagnosis in 1969, he devoted most of his work time to media that could secure his family’s financial future.

Silver Paintings

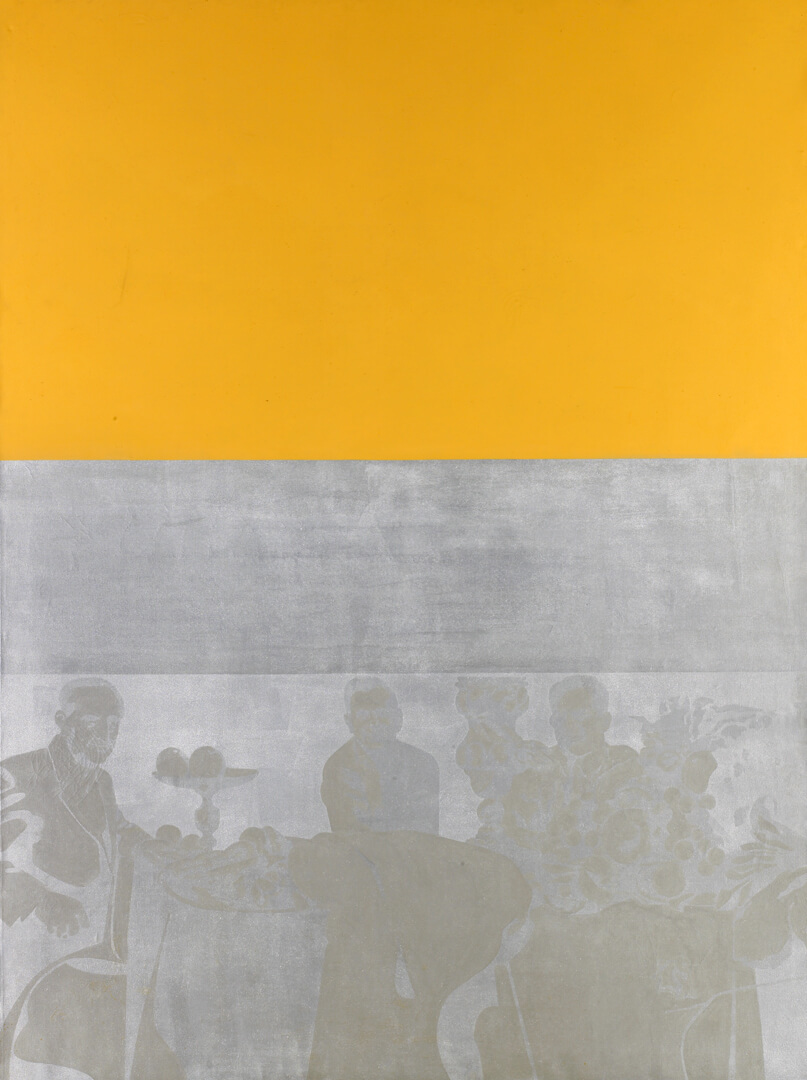

In the mid-1960s Chambers focused his painting on a narrow and radical series in aluminum pigment, which he called silver paintings. Other artists played with this unusual metallic colour at the time, most notably Andy Warhol (1928–1987), some of whose work Chambers knew from trips to New York. The silver paintings provided the illusion of movement in an otherwise still image. As he said at the time in an interview with friend and scholar Ross Woodman, their positive/negative shift (as the viewer moved across them laterally or the light changed) made them “instant movies.” These works tend toward simple, bold imagery, much of it taken from magazines (for example, Plus Nine, 1966; and Three Pages in Time, 1966, where the reference to temporality is also to Time magazine, from which Chambers lifted his imagery).

Chambers writes in detail about the making of these and related paintings:

During the years from 1961 up to 1966, when the silver paintings appeared, I used only plywood panels and modified their surfaces with additional pieces of wood that left them structured in a slight relief. These surfaces were further textured by a glue-and-marble-dust mixture that could be modelled with sandpaper. [Beginning with] All Things Fall, 1963, … I began to spray my surfaces [and] much experimenting was required to learn [how] to use it effectively. Not much spraying to a painting’s surface can be done at one time when it is in a vertical position. Sometimes [a panel] had to be laid flat … or, alternatively, the coats of spray are built up gradually … in a succession of thin applications. Although the surface build-up was there, there was an absence of brush marks. [With] All Things Fall … I first masked out the outlines of larger figures with masking tape to get a clear edge.

My technique changed only a little with the first silver paintings. In preparing the panel the relief build-ups of wood and the marble-dust texture were eliminated. The surfaces of the panels were kept smoother. The figures in … Three Pages in Time and Tulips with Colour Options were masked out as before. [In earlier work, forms] would be painted a specific colour and sprayed while wet with a darker one to be used in the shadows of the cloth. While the paint was still wet, I took a clean brush and moved it over the paint in the light areas of cloth [to] where the shadows were. Working with silver paint, I followed essentially the same steps …. The light areas and shadow areas of an object … were not modelled as in [a] colour painting, but were reduced to outlined shapes, which I then treated in different ways. I would mix a bit of dark paint, an umber or a black with white, to arrive at the tone of darkness I wanted for the shadows. The background was painted in by large brush with silver paint or silver mixed with a bit of pigment for tone. When it dried I masked out my figures using a white chalk outline [and covered the areas beyond the outline with newspaper]. [I then] painted in the shadows [and] sprayed silver paint spiked with varnish over the whole figure [and used] a clean brush [to work] into the sprayed shadow areas [creating] a darker disturbed surface in contrast to the smooth, shiny sprayed-silver surface that had not been touched by a brush. The difference between both surfaces and the surface of the background was … apparent when looking … straight on. When seen from an angle or in a strong lateral light, the allover effect becomes more dramatic. The shiny silver areas become brilliant [and when] viewed from the opposite angle, or lit from the opposite side, the reverse becomes true [dominant]. The areas of the shadow now reflect the shine. The silver paint that was mixed with umber or black catches the light and becomes brilliant. The light silver area fades. This effect has been referred to as … positive-negative … much like the positive/negative terms used in photography.

The spray technique used by Chambers for the silver paintings produced a highly toxic airborne mixture, one that Ross Woodman has speculated was at least partly responsible for Chambers’s leukemia. Chambers’s silver paintings are simple, dramatic, and even aggressive in their manipulation of light and juxtapositions of imagery. They are more closely related to his films than to most of his other paintings.

Multiples

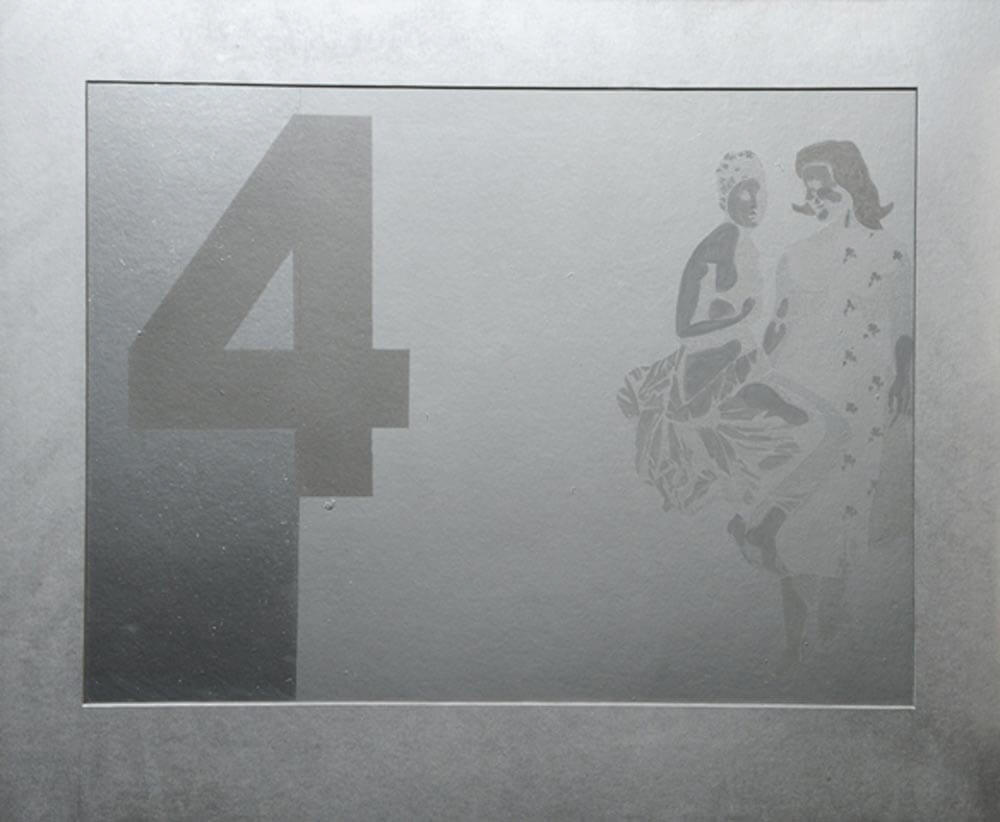

Keen to make smaller work that was more affordable, in 1966 and 1967 Chambers made what he called “multiples” of four of his major silver paintings. Neither serigraphs nor silkscreens, these small works were handmade replicas of the larger paintings (Tulips with Colour Options, Plus Nine, Middle 1, and 4 Gerard). Although Chambers states that he made the multiples after these paintings, a large-scale oil of 4 Gerard has not been located.

Chambers incorporated Neoclassical imagery in 4 Gerard. One of the two figures in the image is based on that of Psyche from a painting by François Gérard (1770–1837), Psyche and Cupid, 1798 (Louvre), giving the work its enigmatic title. Here, not only does Chambers astutely combine a famous couple from European mythology and art history with a reworked contemporary photograph of his wife, Olga, but he also demonstrates that photography was for him in part a sampling technology.

As he said to the author Avis Lang in a 1972 interview, “Photography got paintings … onto postcards and into everyday use. They became available as objects. The museum world became light and reappeared as newsprint …. An Ingres nude can become a contemporary something.” Or in this case, 4 Gerard is also for Olga, in the present.

Chambers also made some conventional print works, the colour photo lithograph Grass Box No. 3, 1970 (45 produced), the lithograph Diego Drawing, 1971 (70 produced), and the lithograph included in the three hundred copies of his autobiography, published by Nancy Poole in 1978.

Plexiglas Drawings

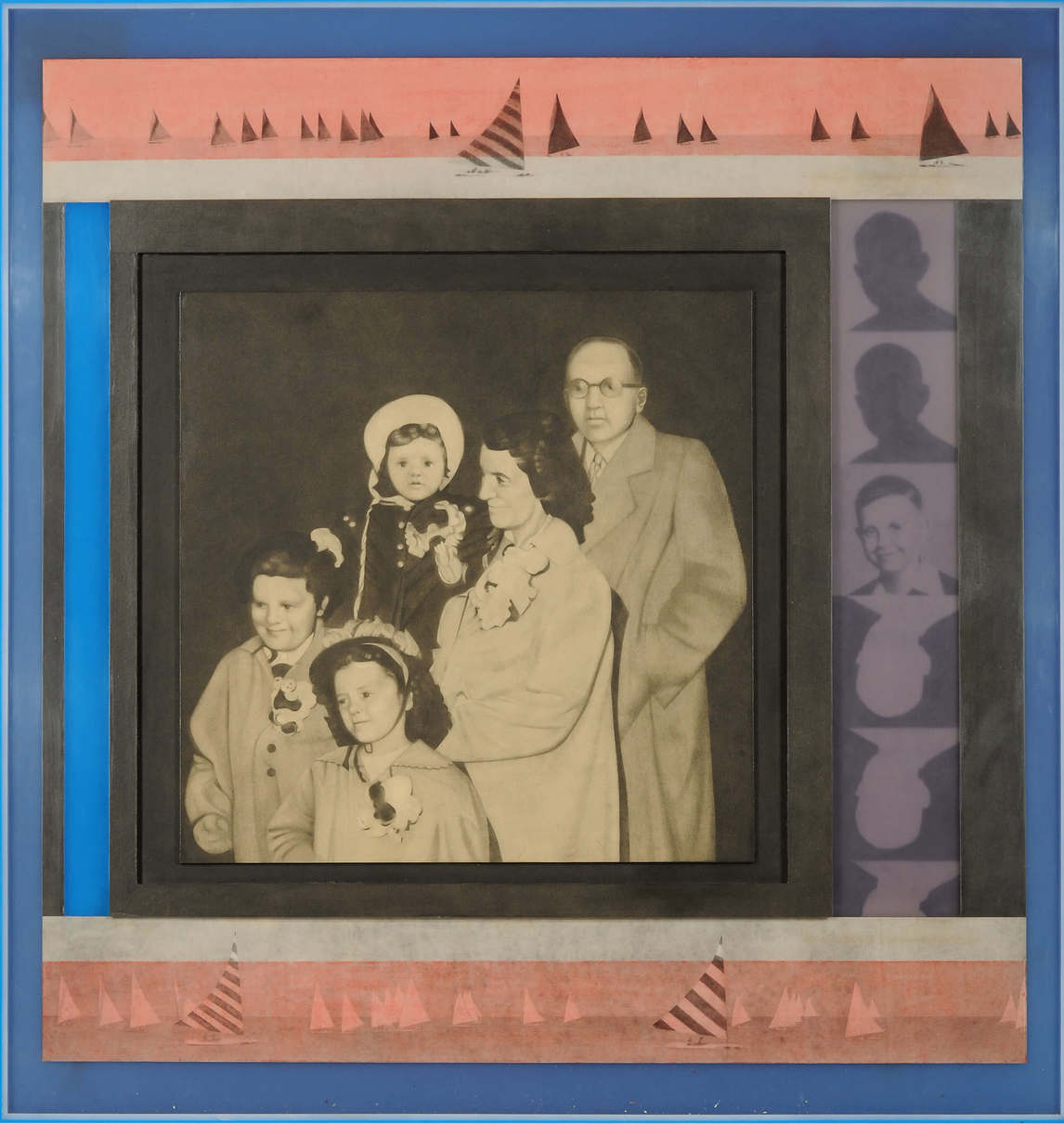

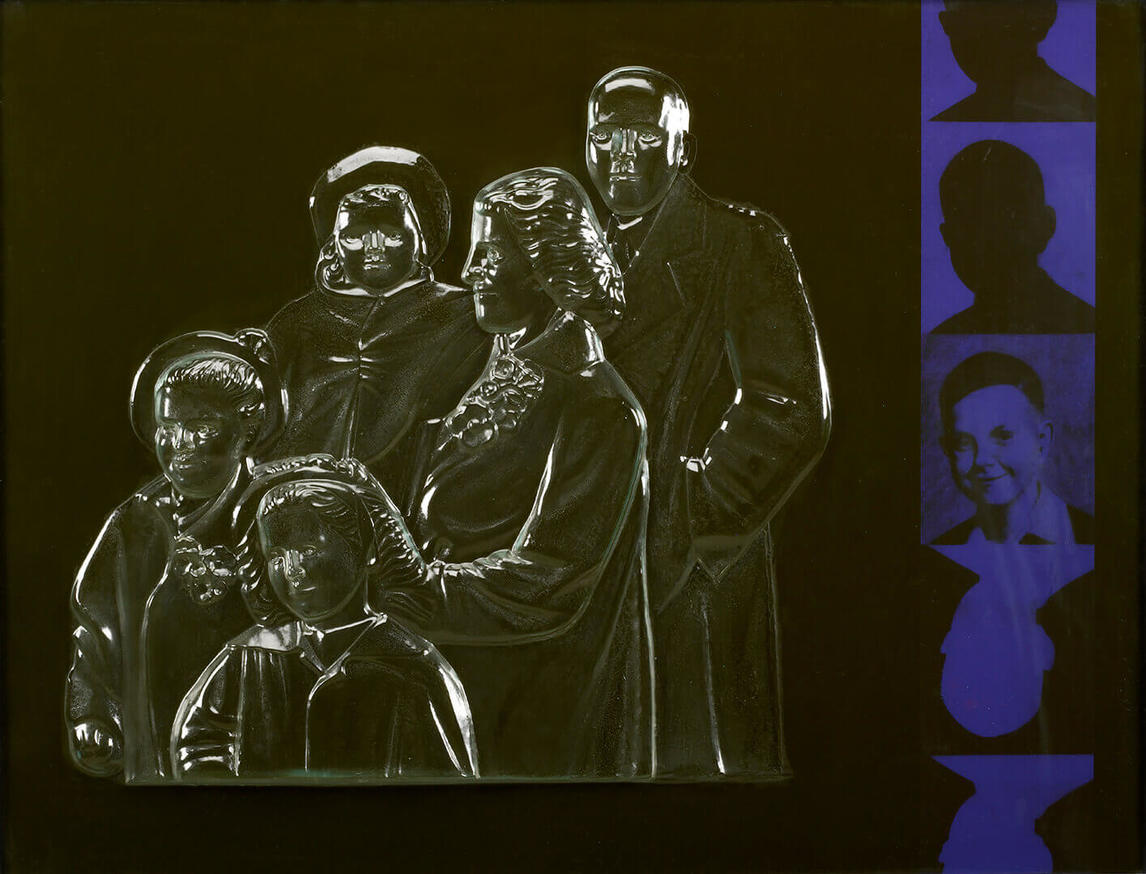

In 1968, finished with his experiments in silver and actively making films, yet still concerned with painting in the broadest sense, Chambers made a remarkably beautiful and intriguing set of works that enclose carefully wrought drawings in highly coloured Plexiglas. The bold imagery of the Regatta works and the exquisite subtlety of the Madrid Windows, all from 1968, are dramatically heightened by this commercial product. One of Chambers’s interests at this time was in three-dimensionality, though not sculpture. The plastic drawings gave him this extra dimension, as did his closely related vacuum-formed pieces from the same time.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements