Jack Chambers’s work is as challenging and controversial today as it was when he made it. He achieved prominence as both a painter and a filmmaker and was vigorous in organizing Canadian visual artists’ rights. His theory of “perceptual realism” challenges parochial notions of regionalism.

Significance

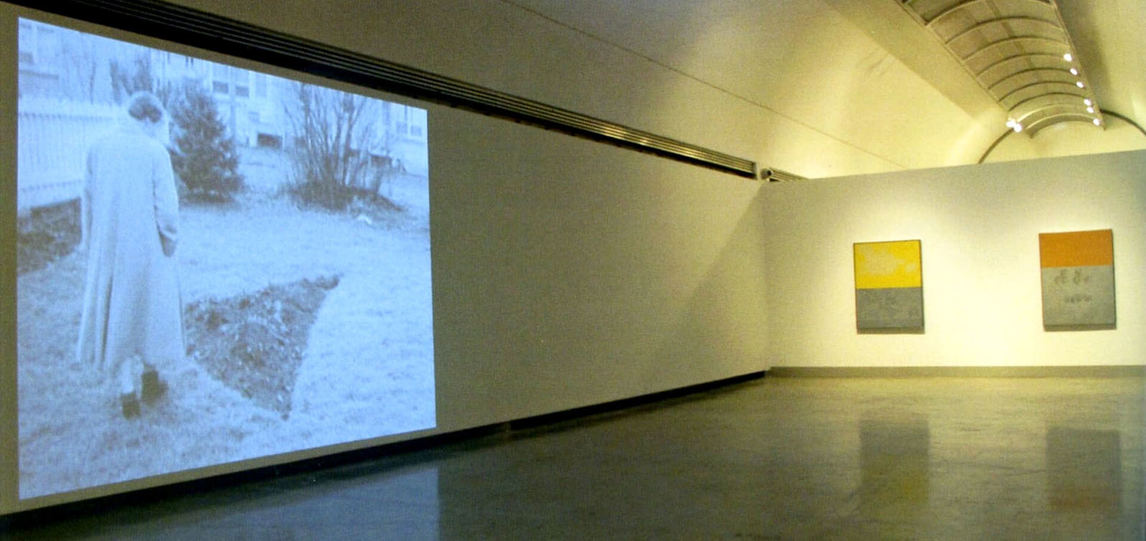

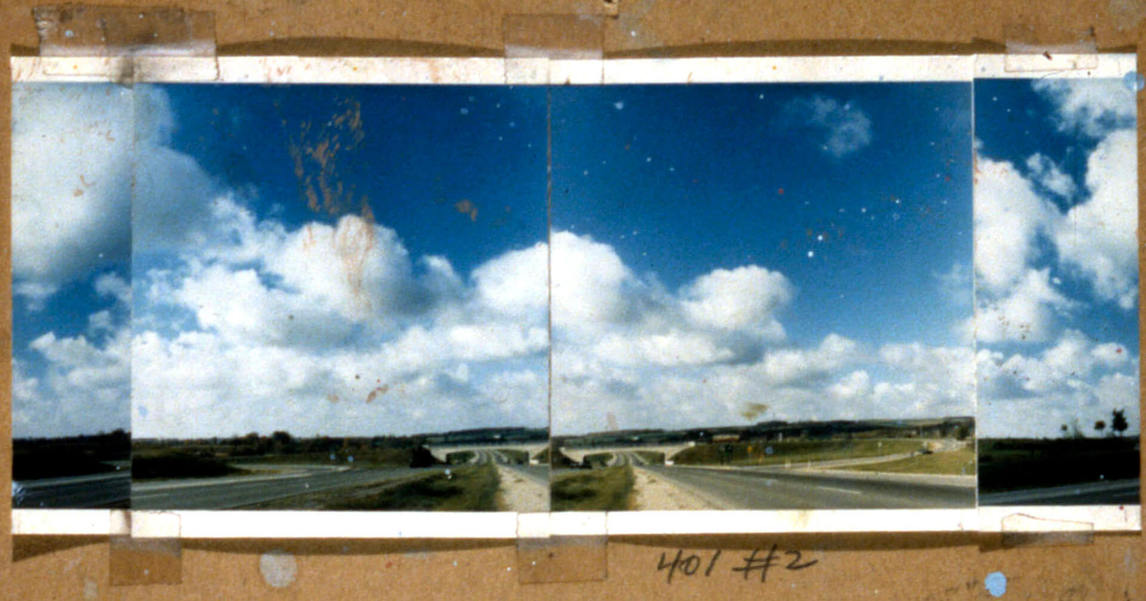

Chambers’s reputation as a painter and filmmaker is unsurpassed in Canada, where he is rightly revered as a professional of the highest calibre and an uncompromising technical and thematic experimenter. His film The Hart of London, 1968–70, is widely regarded internationally as one of the most significant avant-garde films ever made. Paintings such as 401 Towards London No. 1, 1968–69, and Sunday Morning No. 2, 1968–70, are both icons of Canadian art. His theoretical essay “Perceptual Realism,” 1969, is still a touchstone in debates about regionalism, perception, and the spiritual in art.

While Chambers did teach briefly at the University of Toronto and gave public lectures, he led by example more than as a teacher or mentor. A private and complex person, he was also a natural leader whose profile as a committed and productive artist, rather than the style of his work, inspired others in London and well beyond. He did not have followers, but his influence can be seen in the work of Toronto painter Sheila Ayearst (b. 1951) in her series Highway 401, 1995, and in the recent work by London painter Sky Glabush (b. 1970).

Ironically, given Chambers’s devotion to artmaking, perhaps his greatest legacy was his central role in founding Canadian Artists’ Representation (CAR, later CARFAC, with the addition of the French counterpart, Le Front des artistes canadiens) in 1968, a national body that ensures the fair recognition of artists’ copyright. Thanks initially to Chambers and fellow London artists Tony Urquhart (b. 1934) and Kim Ondaatje (b. 1928), by 1975 Canada became the first country to pay exhibition fees to artists.

Critical Issues

Regular exhibitions of Chambers’s work have been held since his death in 1978. Increasing attention has been paid to the importance of his films and to the integration of this part of his work with his better-known output as a painter. Chambers’s experimentation across a range of media remains a topic for further investigation.

Catholicism was central to Chambers’s life after his conversion in Spain in 1957. While he was subtle in his references to the religious—for example, the references to Christmas or Easter in the Sunday Morning paintings—its presence is pervasive and important. Religious and spiritual matters tend to be downplayed in the creation and reception of contemporary art. If we are to think of Chambers as quintessentially and significantly modern as an artist and man, what do we make of the religious dimensions of his work?

To what extent should we consider biographical details when interpreting works of art? Biography is often treated as central in Chambers’s case because of his fatal illness. Yet the assumption that his illness directly affected details of his artworks can be misleading. For example, he began Victoria Hospital, 1969–70, which depicts where he was born and died, before his leukemia diagnosis in 1969.

Was Jack Chambers ultimately a regionalist? On the one hand, he was closely involved with the London art scene and with outspokenly regionalist artists there, especially Greg Curnoe (1936–1992). He depicted the environs of the city and region. On the other hand, Chambers was trained in Spain and kept his eye on the work of friends there. His reputation as an avant-garde filmmaker was international, and his constant technical experimentation was in line with developments in the United States.

The two large Chambers exhibitions mounted in 2011 (at Museum London and Art Gallery of Ontario) gave people the opportunity to rethink his art as a whole and speculate further on particular works. An especially intriguing case is the unfinished status of his large painting Lunch, begun in 1969 and exhibited in 1970 but apparently never completed to his satisfaction. An account of this mystery, by Sara Angel, was published in The Walrus (January/February 2012).

Perceptual Realism

Chambers’s central stylistic and technical contribution to artmaking was his practice of perceptual realism, which he later called simply perceptualism. A significant if difficult to read art theorist, Chambers expounded his ideas in a landmark 1969 article, “Perceptual Realism.” He wrote the essay because he believed that distinctions needed to be made among types of realism and because he felt his own approach was unique. The fruit of years of intense reading in phenomenology (that of twentieth-century French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty especially) and hard thinking, the essay ranges over technical, philosophical, historical, and spiritual ground.

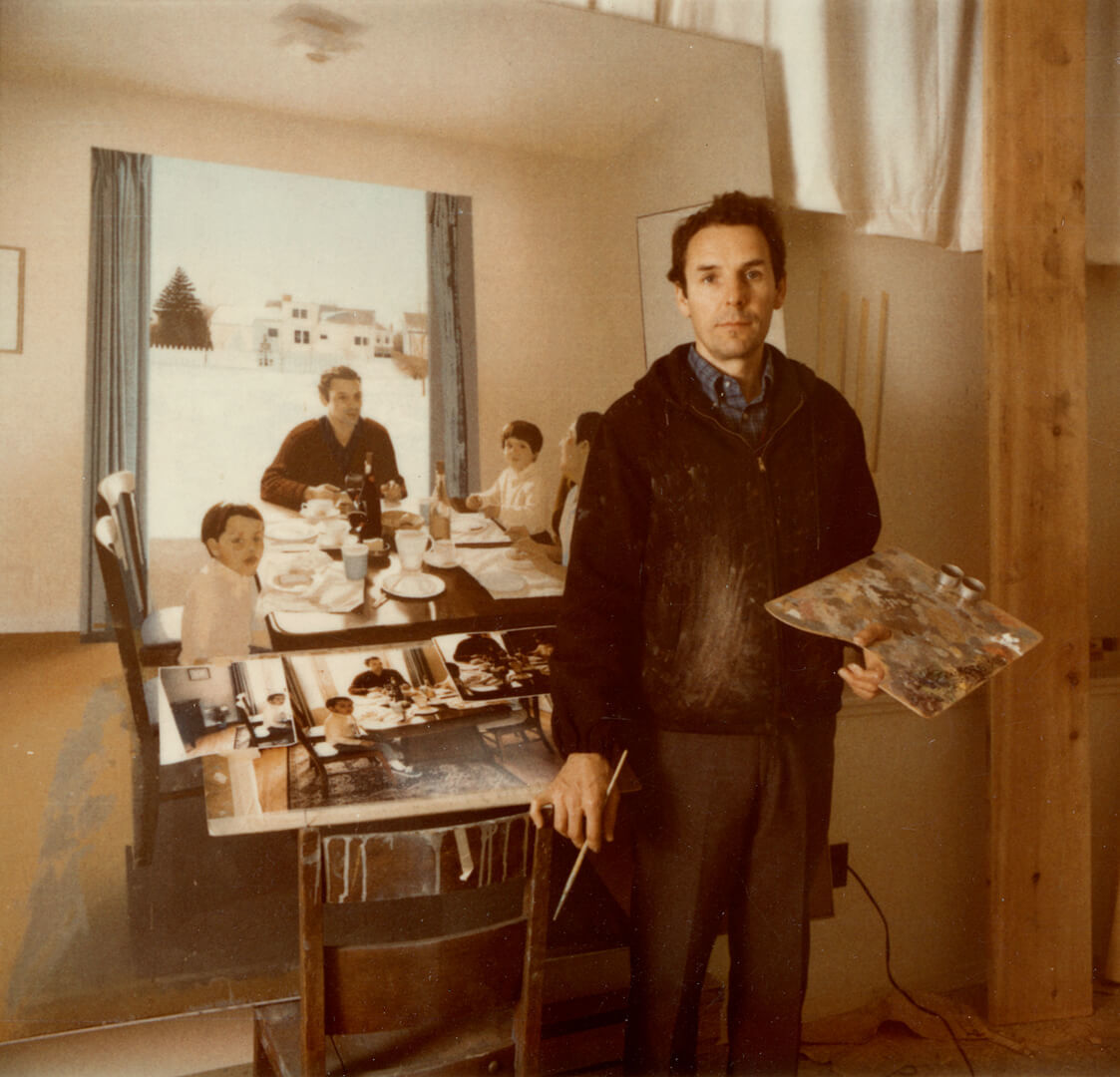

Perceptual realism is a profound reflection on primary sensory experience, not simply a reproduction of it (Chambers largely disdained contemporary American Photorealism). His examples in the 1969 article were 401 Towards London No. 1 and Sunday Morning No. 2, both begun in 1968 though completed, as the essay was, after Chambers learned of his dire health situation. Perceptual realism was for Chambers a new type of realism, one that went to the essence of matter through light and material.

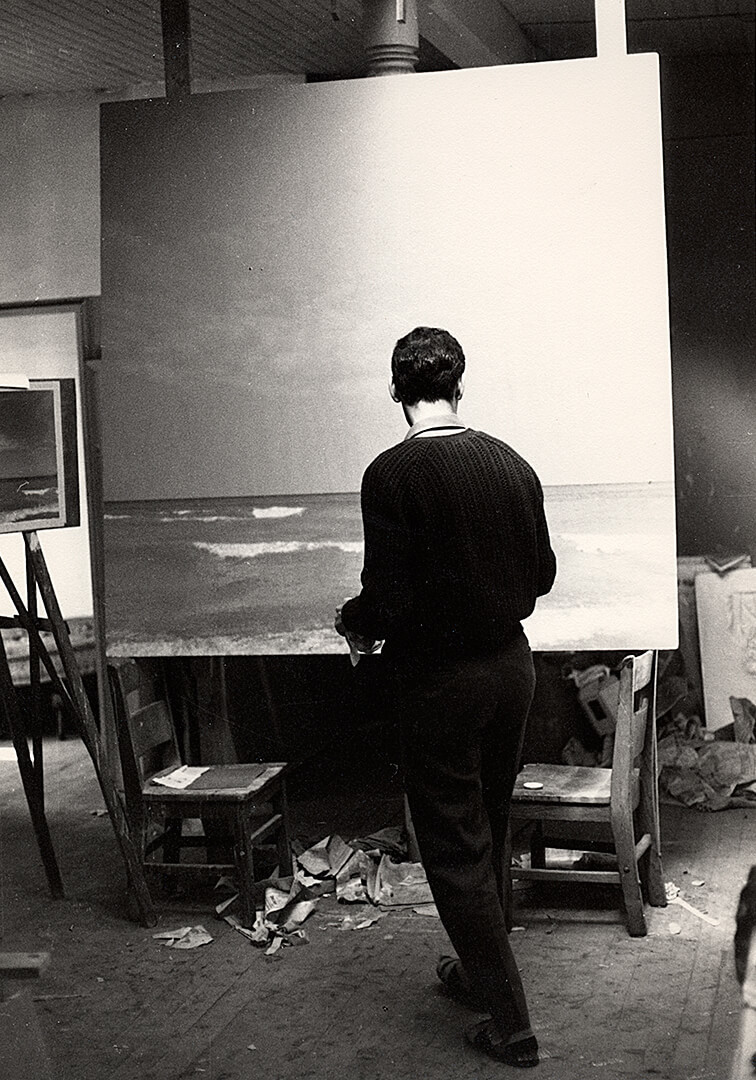

His descriptions of it could tend to the poetic: perceptualism is “a faculty of inner vision where the object appears in the splendour of its essential namelessness.” At the same time, it was material and visible, dependent on his own amateur photography to get the details of perception right and to allow him the time to produce his large paintings. Perceptualism was in his view far superior to photography in its realism and truth to experience. Photography was a tool; painting and film were the vehicles of spiritual enlightenment.

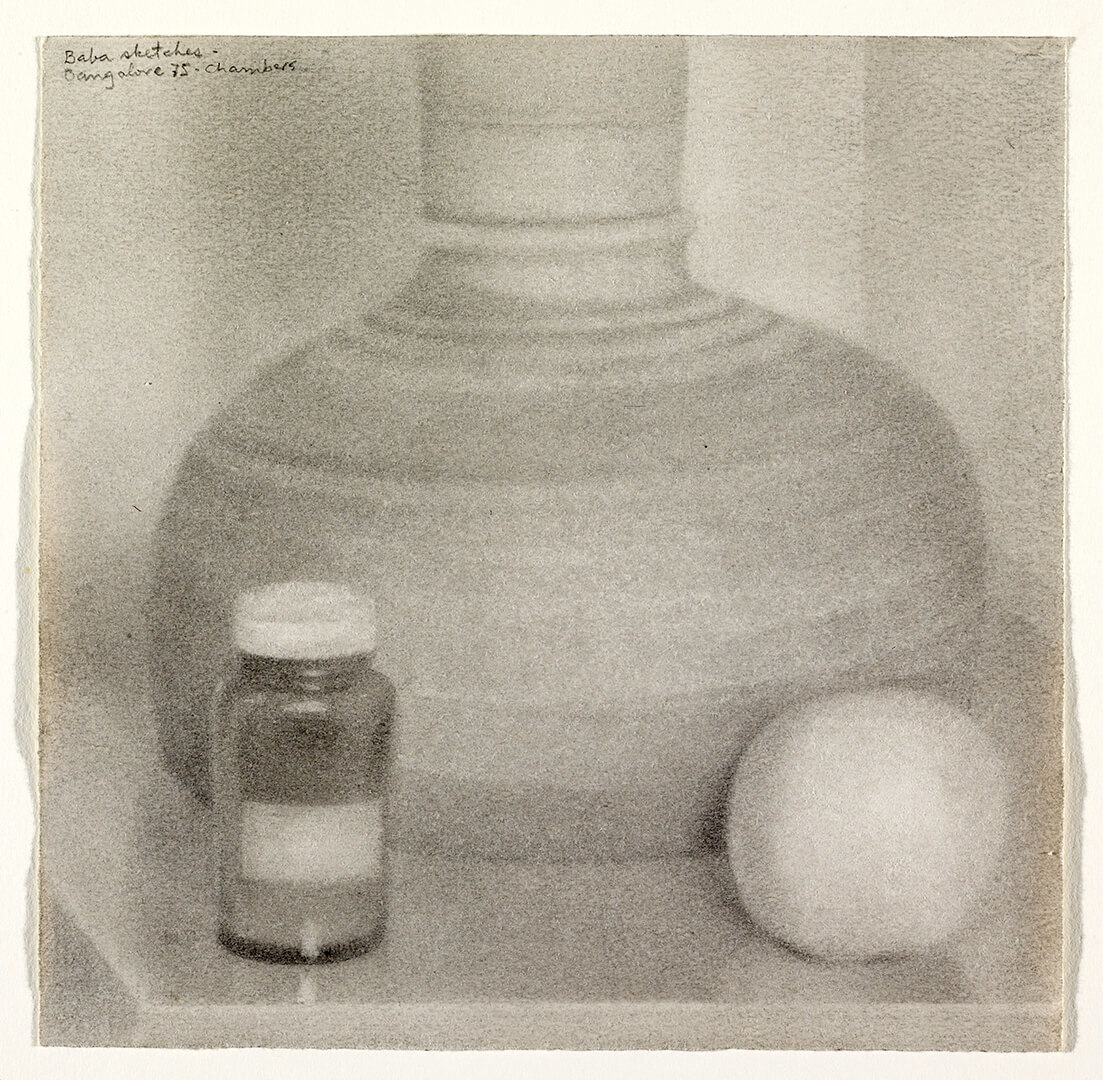

Chambers refined his perceptualism up to his death in 1978; the late Lake Huron works are prime examples. He also worked on films, especially the unfinished (but privately screened) C.C.C.I., 1970. He travelled often and widely during the 1970s, in search of a cure for his disease and for spiritual solace as well as for his work for Canadian Artists’ Representation. In Bangalore, India, in 1975, where he followed the teachings of the Indian guru Sai Baba for some months, he worked with materials that were at hand: pencil, chalk, and paper.

As delicate and evanescent as his health at this time, these and related drawings from the final years of Chambers’s life mark a new, unbidden style, one that nonetheless harmonizes with his earlier, more robust instantiations of light, movement, and intimacy.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements