Homer Watson’s early canvases emphasize draftsmanship and detail. From there he quickly adopted a modified approach that relied upon rich brushwork and increasingly limited tonalities. To appeal to audiences and especially to convey his deeply personal reactions to his subject matter, he attempted to update his style—particularly his use of colour—but with mixed results. What never changed was his determination to convey nature’s power and intensity, an approach that grew from a deep respect for the natural world, and from a desire to emulate it in art and ensure its preservation.

Subject Matter and Media

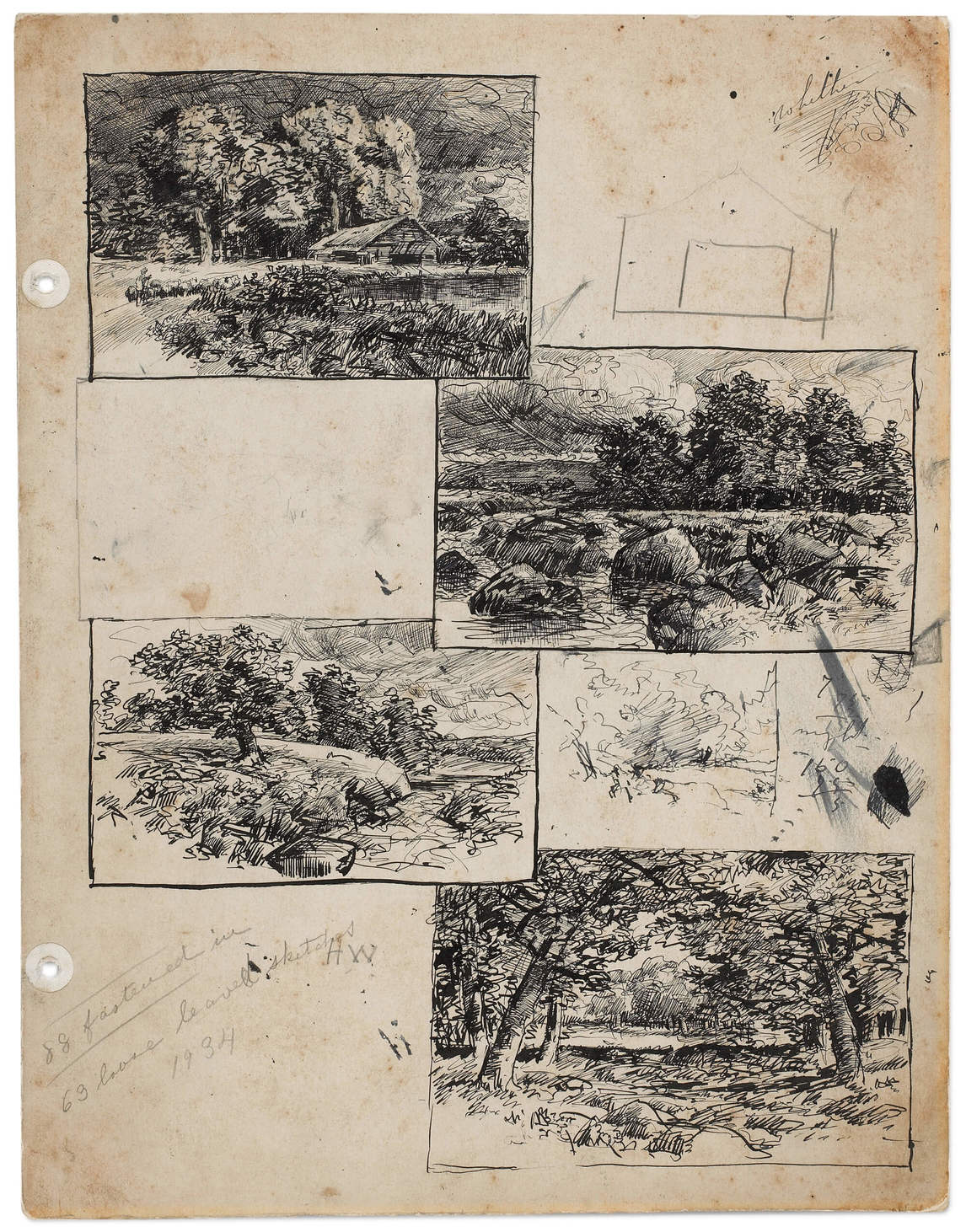

Homer Watson was a prolific artist. His many hundreds of oil paintings range in size from small to very large. Moonlit Stream, 1933, for example, measures about 32 x 42 centimetres, whereas A Coming Storm in the Adirondacks, 1879, is almost 86 x 119 centimetres, comparable in size to other major canvases from Watson’s early years as a professional artist. He also filled multiple sketchbooks with drawings, and in 1889–90 completed etchings of six subjects. His earliest work consists largely of Romantic narrative drawings and paintings, often on literary themes. The best-known and most accomplished of these is The Death of Elaine, 1877, based on the Idylls of the King cycle of poems by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (published 1859–85). After his early twenties, he devoted himself almost exclusively to landscapes. The overwhelming majority of these depict scenery in and around his hometown of Doon, Ontario, where—except for one extended and six shorter stays in Great Britain, and brief trips to various other parts of Canada as well as the United States and France—he spent his entire life.

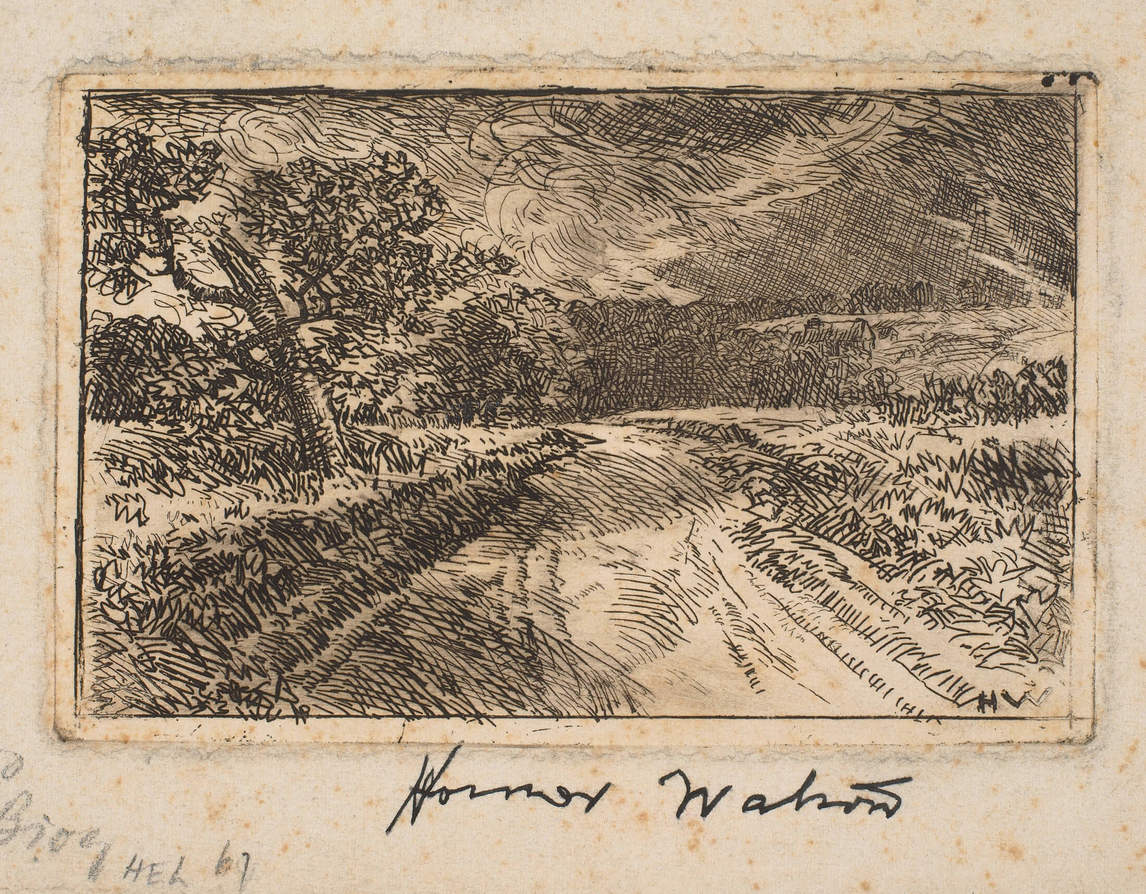

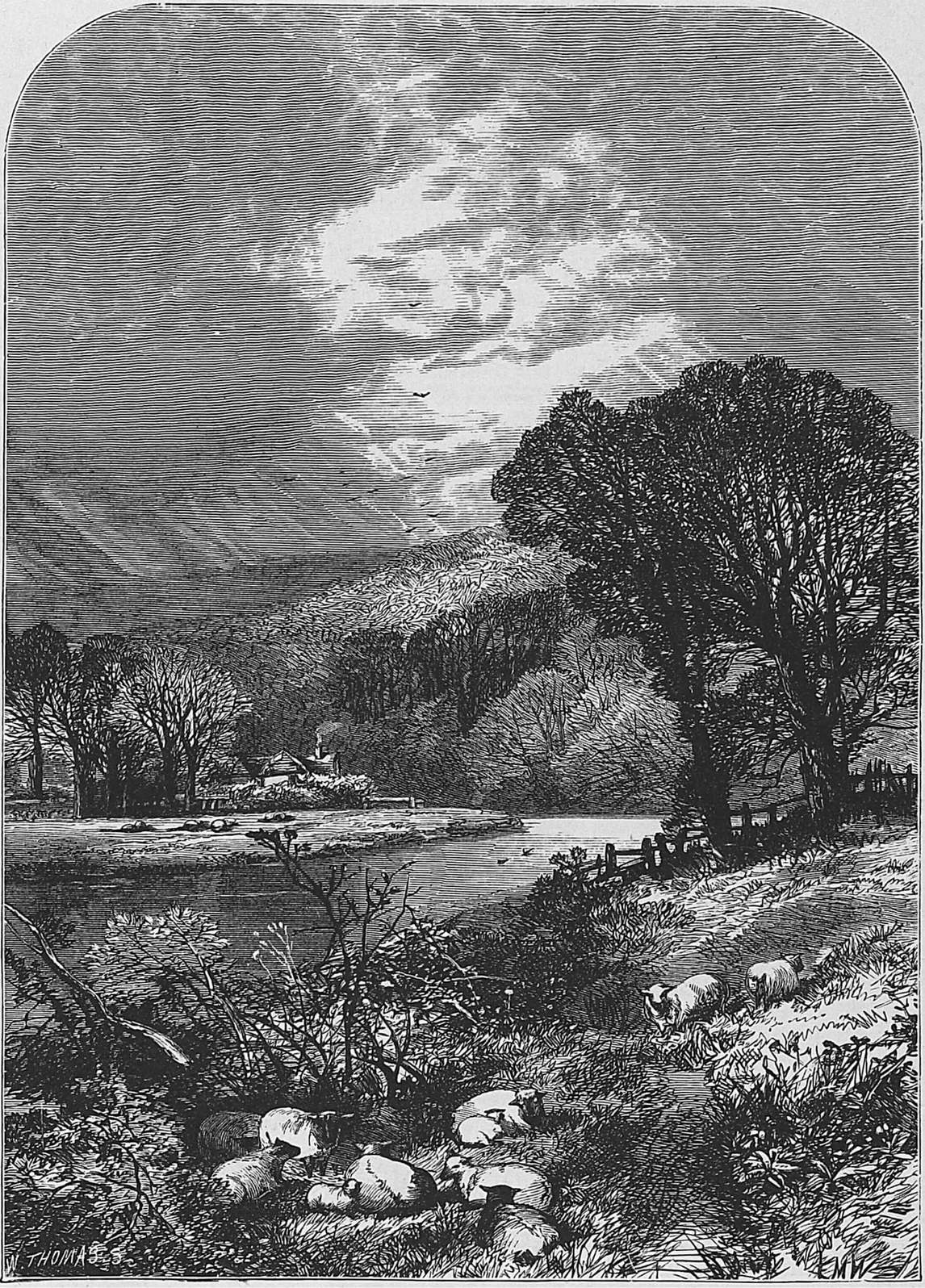

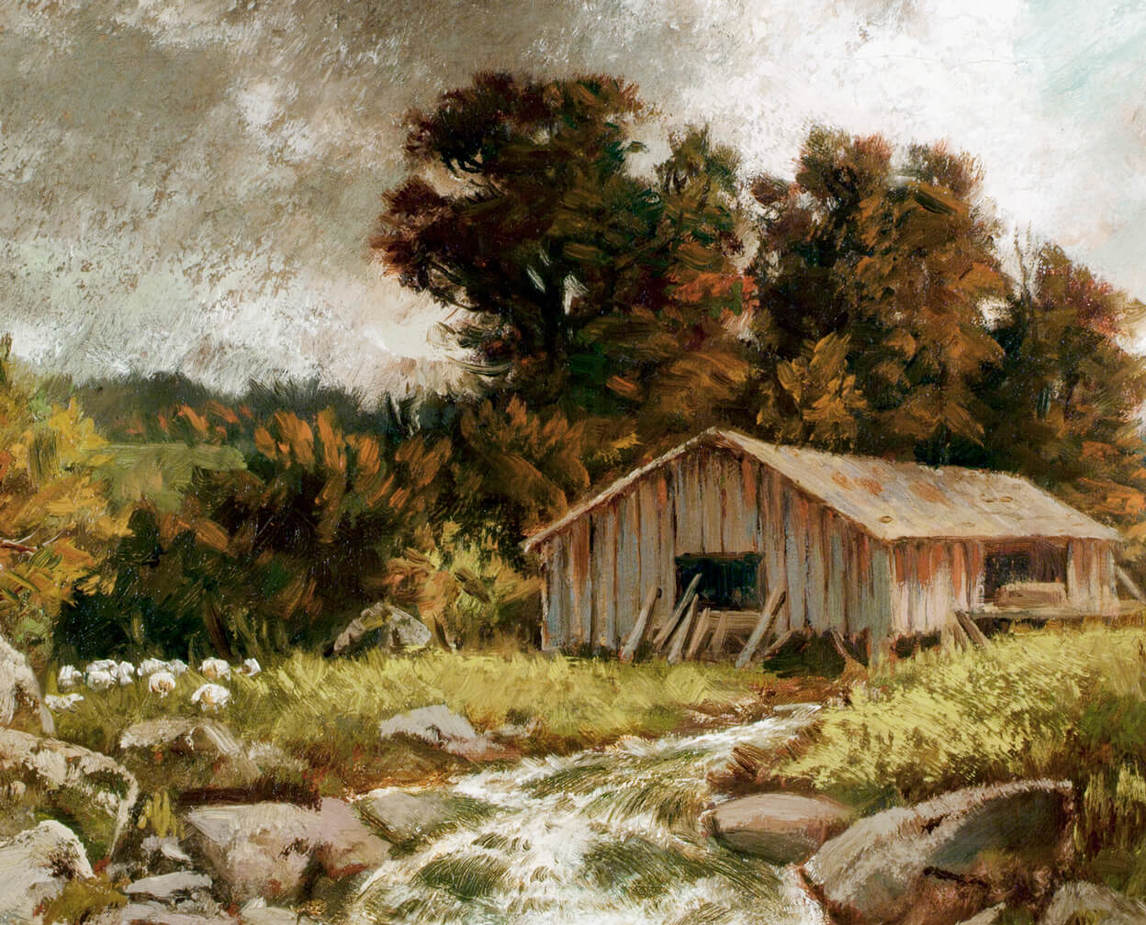

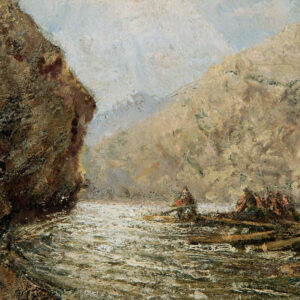

Watson had a strong interest in nature’s power and drama. This fascination probably derived, at least in part, from woodcuts and engravings in the illustrated books and periodicals, such as the American journal The Aldine, that his family owned when he was a boy. These media often exploit sharp contrasts between dark and light areas of the image, contrasts that seem to be reflected in Watson’s predilection for the dramatic cloud formations associated with stormy weather. Turbulent skies, with their contrasts of light and dark, appear frequently in the early years of Watson’s career, in his sketchbooks and in such canvases as River Landscape, 1882; Near the Close of a Stormy Day, 1884; The Flood Gate, c.1900–1; and The River Drivers, 1914 and 1925.

But above all, Watson’s psychological and emotional attachment to nature was premised on the harmonious relationship between landscapes and humanity. Morning at Lakeview, Ontario, 1890, with its three tiny figures arranged in a landscape that is protective rather than threatening, is typical of his bringing together the human and natural worlds. So is the bucolic Log-cutting in the Woods, 1894. “We cannot think of any form of nature that will be complete apart from man,” Watson wrote, “nor is it pleasant to think of man apart from his relation to the soil.”

John Constable and Barbizon Painting

Given Watson’s preoccupation with local landscapes and with human–nature interaction, it is unsurprising that the artists with whom his work was most often associated were the English landscape painter John Constable (1776–1837) and such French Barbizon artists as Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), Charles-François Daubigny (1817–1878), Narcisse Díaz de la Peña (1807–1876), Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867), Constant Troyon (1810–1865), and Jules Dupré (1811–1889). In the 1893–94 frieze that he painted on the walls of his studio, Watson included the names and invented landscape paintings of five of those artists: Constable, Millet, Daubigny, Díaz de la Peña, and Rousseau.

The thematic, formal, and psychological similarities between Watson, Constable, and the Barbizon artists were strong. All were emotionally and psychologically devoted to landscapes with whose topography and inhabitants they were closely familiar—seen, in Watson’s case, in images such as Two Cows in a Stream, c.1885; In Valley Flats near Doon, c.1910; and The Flood Gate, c.1900–1, among many others. Watson repeatedly argued that any landscape painter’s richest and most meaningful work is done where “every familiar scene is hallowed with a glamour which gives a charm the attractions of a strange land can never give, and he paints it with a soul.”

However, when similarities between his art and that of Constable and the Barbizon artists were first proposed (in 1882, most famously by Oscar Wilde), Watson had never seen original work by any of those artists. While he acknowledged the points of comparison, he was also at pains to proclaim that he was painting independently of the Europeans, even if his work seemed to run along parallel lines.

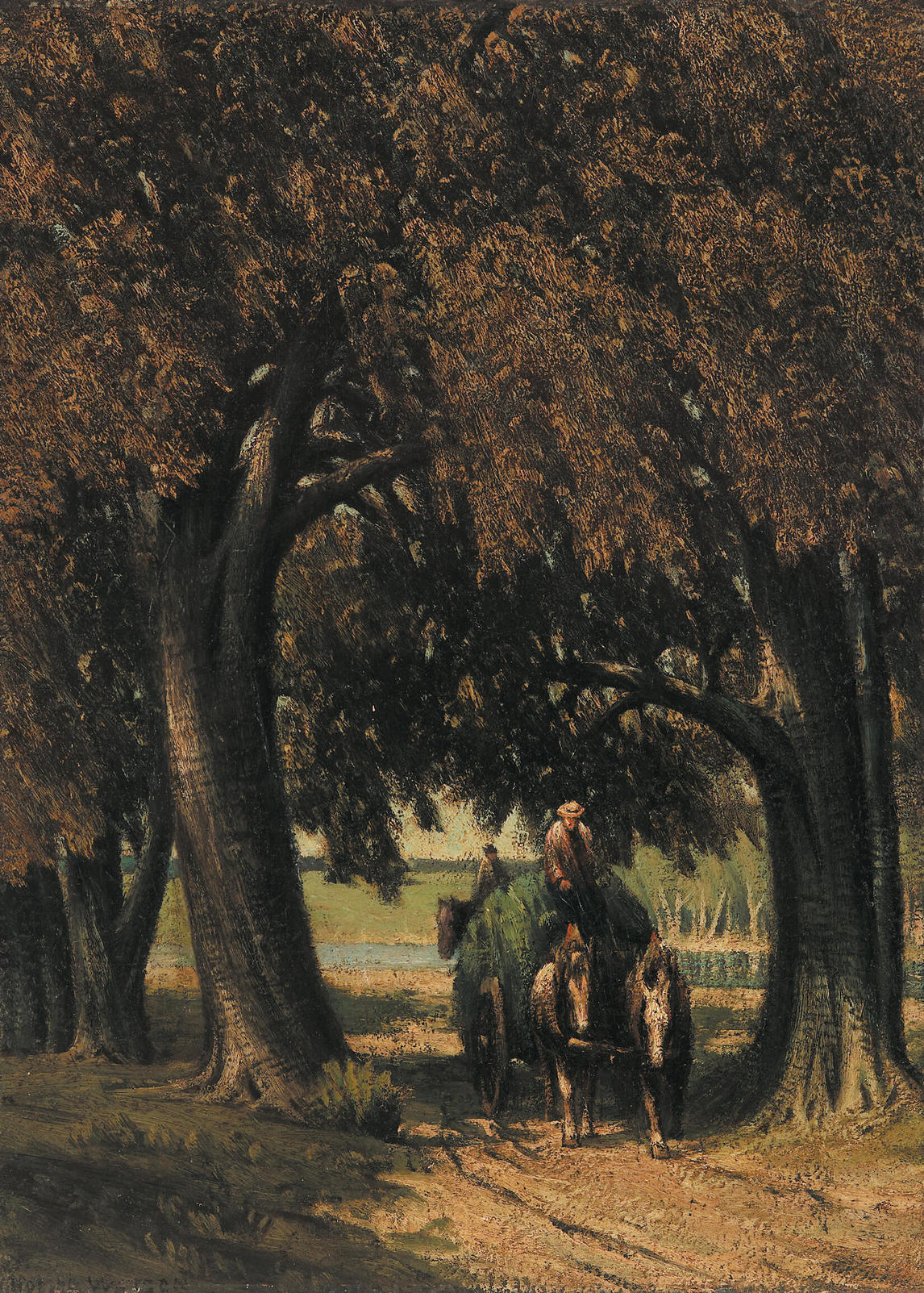

Watson and the European artists’ commitment to rural landscapes to which they had personal connections was only one of their similarities. Equally important was their mutual attempt to express the importance of nature not through precise detail—as Watson had done in his earliest paintings, influenced by the Hudson River School’s prioritizing of optical veracity (The Pioneer Mill, 1880, and The Stone Road, 1881, for example)—but through the use of broad pictorial effects whose sweep and power suggest pervasive moods that convey nature’s underlying vitality and significance (as with Near the Close of a Stormy Day, 1884, and many others). In the United States this style reached its apogee in the work of George Inness (1825–1894), whose highly personal and poetic approach to landscape painting was undoubtedly important to Watson. Although the foreground of an early work such as A Coming Storm in the Adirondacks, 1879, relies on precise draftsmanship to bring out a wealth of detail in the rocks and trees, it is the sky—with its broadly brushed clouds and its generally dark tonality—that points toward the blurred outlines, the suppressed detail, and the unifying atmospherics of later canvases such as Country Road, Stormy Day, c.1895, and the magisterially moody The Flood Gate, c.1900–1. Hence, too, Watson’s partiality to “grey” days, as in A Grey Day at the Ford, 1885, and to the times just before or just after rainstorms, when (as in Before the Storm, 1887, or After the Rain, 1883) the air has a physicality that unites diverse details into a shimmering unity.

All great artists, Watson stated, followed a similar trajectory, beginning their careers by concentrating on the analysis of detail but progressing from there to the submerging of individual objects through the massing of form and the synthesizing effects of light, colour, and atmosphere. Thus Constable, in Watson’s evaluation, reached maturity by adopting (in paintings such as The Hay Wain, 1821) unifying colour schemes that treated “the moods of nature . . . in a . . . broad manner.” Similarly, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875; The Oak in the Valley, 1871)—one of the Barbizon artists most admired by Watson—“does not insult the intelligence” of viewers

by telling them a lot [of] trivial small matters. . . . He felt[,] as he doubtless expected you should feel when you are enwrapped with a sentiment or love of nature’s beauty at the close of day, that in the mystery of the light at that hour you are filled with a fine thought of the spirit of the scene, that you have implanted in you then an idea of the law of nature’s general harmony.

The British critic R.A.M. Stevenson was one of many viewers who identified a commitment to broad and evocative pictorial effects as a crucial point of contact between Watson and the Barbizon artists. At the same time, though, he commented on the Canadian artist’s occasionally “rude” and “uncultured” approaches to picture making. This was not entirely a criticism. Stevenson attributed Watson’s “rudeness” in part to a lack of experience. But he also suggested that the largely self-trained Watson’s sometimes unsophisticated expressive strength, which resulted in occasional faults in his depiction of individual objects, opened the door to the creation of unifying effects—something that Stevenson saw as Watson’s forte.

Thus, the artist’s loose brushwork and broadly delineated forms in such canvases as Log-cutting in the Woods, 1894, and especially The Flood Gate, c.1900–1, conveyed a satisfyingly Barbizon-like sense of nature’s internal consistency, poetry, and harmony. These were qualities intended by Watson and admired by Stevenson, both of whom were skeptical about landscape paintings that looked cobbled together out of separate elements and weighed down with unnecessary detail. Similarly, in 1896 the Canadian artist and critic Harriet Ford (1859–1938) praised Watson’s “desire to express with breadth the large things of nature, the mystery and charm, the dignity of things, which live close to life.”

Paint Application and Tonality

Watson employed two means to achieve his broad effects: heaviness of paint application and subdued tonalities. The first of these, paint application, began to change in the early 1880s. Prior to that point, in canvases such as The Castellated Cliff and A Coming Storm in the Adirondacks, both from 1879, he often treated the brush as if it were a pencil: a tool for drawing. By the early 1880s, however, he was producing canvases such as After the Rain, 1883, in which draftsmanship is much less evident in the forms and details. That tendency intensified around the time of his first visit to Europe, from 1887 to 1890. It would increase even more throughout much of the nearly half century remaining in his working life, achieving some of its strongest statements in such canvases as the impasto-laden The Flood Gate, c.1900–1.

Feeling that he was better equipped by temperament and personal history to paint Canadian rather than British landscapes, Watson maintained that nature in Canada consisted of “strong forces” that called for sturdy paint application in order to reveal their “vital truth.” For example, in The Hillside Gorge, 1889, he exploited the brush to apply paint in broad strokes that convey a sense of a bracing wind. Later, with The River Drivers, 1914 and 1925, he combines an austere landscape with a sky exploding with light and motion.

In conjunction with his increasingly rich paint application, Watson limited his palette to a generally narrow and cool tonality with a few muted highlights, a development that had begun during his first visit to Britain and that led to such canvases as Country Road, Stormy Day, c.1895. The Toronto art dealer John Payne, for example, wrote in 1888 of his admiration of Watson’s British canvases, which he nicknamed “the browneys.” “One of the vices of Canadian colouring,” in the view of an 1887 observer, “is its warmth not to say loudness, and Mr. Watson’s work has been a protest against this fault.” Twenty-six years later, in 1913, a newspaper reviewer accurately described Watson’s favourite colours—seen in, for example, Below the Mill, 1901—as “deep rich browns and siennas balanced with touches of bright greens and dull reds.”

At his best, as in Summer Storm, c.1890, Watson used tonality as one tool for the creation of a powerful sense of place, atmosphere, and mood. As his choices of colours became more restricted, however, some commentators complained that he was becoming monochromatic but without establishing the kind of powerful mood that he had produced in, for example, River Landscape, 1882; Near the Close of a Stormy Day, 1884; or Country Road, Stormy Day, c.1895. As early as the mid-1890s he was occasionally being criticized for what the traditional academic artist Wyly Grier (1862–1957) described as a preoccupation with style and technique for their own sake. In 1904 a Montreal reviewer protested that “the tone of some of [Watson’s paintings] recalls strangely some of the old mezzo-tints,” and that this—combined with the “whacking on [of] plenty of pigment and varnish”—resulted in a “hopelessly artificial style.” Four years earlier another reviewer had lauded the “force and individuality” that made Watson “without a doubt one of the best landscape painters we have.” That writer nonetheless worried that the work could become “too heavy and gloomy and pigmental, and that to see too many of his canvases at a time gives one a sense of depression.”

The artist, however, was as unrepentant about his sombre and restricted colour schemes as he was about his heavy paint application. For Watson, canvases such as The Load of Grass, 1898, among others, had nothing to do with the sense of oppressiveness that increasing numbers of critics found in them. Instead, he expressed concern that the Impressionists had made a fetish of pure, highly saturated colours, and contended that their paintings were exercises in working through technical problems rather than being vehicles for conveying the magnificence of nature itself. As Watson’s tonalities became darker, strength of lighting became an important consideration in the hanging of his work. The most frustrating example of this occurred early in the twentieth century, when The Flood Gate, c.1900–1, was returned to him because the lighting in its first purchaser’s home, as well as in another venue to which the painting was loaned, was too low for such a dark canvas.

Post-1920 Paintings

Soon after the end of the First World War, Watson began experimenting with colours that were often brighter and more diverse than those he had generally favoured during the previous two decades. For example, Emerald Lake, Banff, painted after 1920, sets up a striking contrast between light and dark. In works such as this Watson was perhaps paying more attention to the chromatic palettes of Impressionism, although there is little in his writings to confirm that he had any significant understanding of, or engagement with, the Impressionists or, indeed, of other modernists, almost all of whom preferred brighter, purer colours than he used. The chromatic scheme of Moonlight, Waning Winter, 1924, is made up largely of variations of white, along with light pinks and purples. Purple also became more pervasive in Watson’s depictions of clouds and skies during these years. Other paintings feature rich foliage presented in comparatively muddy shades of orange or rusty red—for example, The Valley of the Ridge, 1922.

Besides their use of new and often unnatural colours, Watson’s late paintings broke new ground for him in their relatively tight focus. During the 1880s and 1890s especially, but also during the first two decades of the twentieth century, his more ambitious paintings had been studio constructions: expansive views that he built by modifying and combining plein air drawings of individual motifs. After the early 1920s, however, close-up landscape views, rather than the broader composite scenes of his earlier years, came to dominate his work.

In part this was because of the artist’s declining health, which made it difficult for him to undertake large, complex canvases. A second factor, however, was his 1923 acquisition of an automobile. That purchase enabled Watson to make painting trips that would otherwise have been too physically demanding. Now, unencumbered by the need to minimize the amount and weight of his equipment, he was able to paint directly onto sturdy panel supports in the immediate presence of his open-air subjects. Moreover, he often did not repaint the resulting views onto canvas, or even do further work on them, once he was back in his studio. This seems to have been the case with, for example, Storm Drift, 1934, which he painted directly onto board without later transferring it to canvas. Watson’s paintings from these years thus tended to be produced more quickly than in the past, and the relationship between the finished images and the natural scenes that had inspired them became less mediated. In many cases, too, the paint was applied with a new degree of liveliness, thickness, and energy.

Watson’s career-long resolve to convey the immediacy and power of nature thus remained unchanged during his final years. The thick impasto and dynamic brushwork of his late paintings—Moonlit Stream, 1933, and High Water, Pine Bend, c.1935, for example—continued what had always been his determination to seek out the forces that drove the natural world. What was paramount, during the 1920s and 1930s, was the degree to which those forces were implied in the immediacy and the gestural violence of oils such as Speed River Flats near Preston, c.1930. These late works in effect mimicked, in their rough physicality, the forces and the grandeur that Watson had always believed existed just beneath nature’s surface.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements