Homer Watson’s letters, his unpublished manuscripts, and his paintings, drawings, and prints document the issues that most interested him as an artist. Of his concerns, the commemoration of southern Ontario’s pioneers and early settlers and the visual expression of Canadian regional and national identities locate Watson firmly within the milieu of many of his fellow artists of the time. In addition to these priorities, his dedication to safeguarding the natural environment was exceptional and far-sighted.

Ontario’s Pioneer Memory

Homer Watson was a grandson of German and British settlers of Ontario’s Waterloo County, something of which he was very proud. He occasionally dealt explicitly with pioneer subjects, in canvases such as The Pioneer Mill, 1880, and Pioneers Crossing the River, 1896, and in preparatory drawings such as a detailed study for a canvas titled A Land of Thrift, c.1883. Images such as November among the Oaks, c.1920, depict the results of early nineteenth-century settlement by portraying nature harmoniously coexisting with the human presence. That presence could take many forms—people, farm animals, fences, crops, mills, and other buildings—but it was almost always there. Watson’s paintings are in many ways Canadian art’s most consistent and loving visual documentation of the pioneer legacy in Ontario’s historical sense of identity. Yet beneath their reassuring and often bucolic surfaces, Watson’s landscapes raise difficult questions about the history of European settlement in Canada.

In recent years pioneers and settlers have become subjects of debate. Indigenous groups around the world demand that the descendants of pioneers recognize their status as members of privileged collectives. Settler societies tend to replicate their histories and beliefs in their new communities, often at the expense of Indigenous populations that substantially predate the arrival of non-Indigenous pioneers. The Anishnaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Neutral (Attawandaron) peoples had been living in the Grand River area (including what later became Waterloo County) for centuries. Before the early nineteenth-century arrival there of the first pioneers, the British government formally granted the land extending six miles on either side of the full length of the river to the Haudenosaunee, in the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784; but First Nations title to the land continues to be disputed to this day.

During Watson’s lifetime Europeans regarded pioneers and settlers as highly admirable people who homesteaded what was considered an empty wilderness. Rather than being viewed through a critical lens, pioneers were characterized almost entirely as having traits such as resilience, resourcefulness, an immense capacity for work, and an aversion to complaining about hardships. They stood for ideals of stability and human control. This was especially the case during the decades from the 1850s to the 1880s, when transportation networks were expanding, cities were growing, and traditional family-run businesses were giving way to impersonal, large-scale operations. The extent of change in Waterloo County may be gauged by the fact that during the 1890s the population of the federal electoral district of Waterloo South was 47 per cent rural and 53 per cent urban. Just a short time earlier it had been overwhelmingly rural.

It was precisely because pioneers represented solidity and independence that the Toronto Industrial Exhibition yearly featured a walk-through “pioneers” display with a log cabin built on site, using pioneer methods. Similarly, the large painting Logging, 1888, by George Agnew Reid (1860–1947), though painted in Paris, was set in pioneer-era Ontario. Reid also planned a mural cycle, for the Toronto Municipal Buildings: Hail to the Pioneers, Their Names and Deeds Remembered and Forgotten, We Honour Here. (Only two of the murals were completed: The Arrival of the Pioneers, 1899, and Staking a Pioneer Farm, 1899.)

Regional Imagery and Canadian Art

In his catalogue essay for the 1963 Watson retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, J. Russell Harper contended that Watson was “as it were, the man who first saw Canada as Canada.” Landscape was a preoccupation for Canadian artists during the second half of the nineteenth century, and questions about the Canadian-ness of their work were timely. Public interest in the country’s varied geography was encouraged by the proliferation of outdoor sketching clubs; by illustrations in publications such as Picturesque Canada (beginning in 1882), Canadian Illustrated News (1869–83), and L’Opinion publique (1870–83); and by rapid railway construction from coast to coast. Visual artists responded to that popularity, with landscape quickly establishing itself as a central theme in art exhibitions during the last four decades of the nineteenth century.

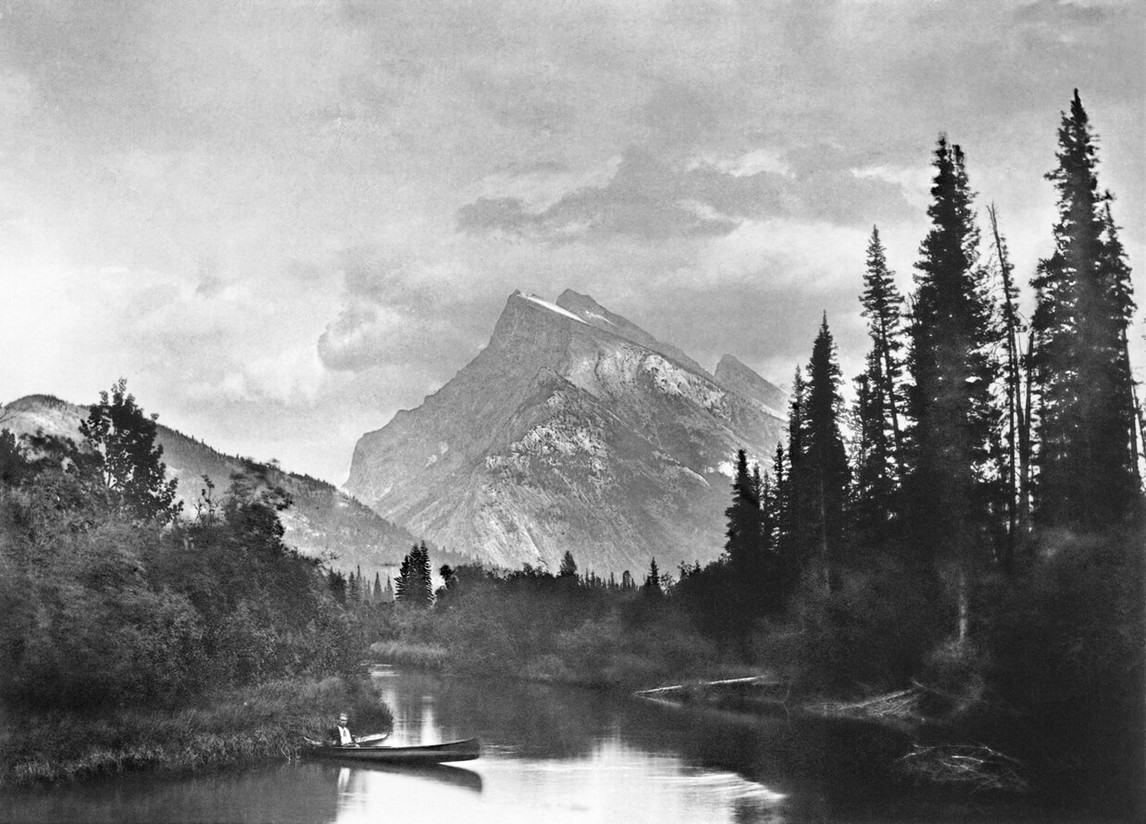

Watson had many landscape artist peers—including Lucius O’Brien (1832–1899), Marmaduke Matthews (1837–1913), John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898), Allan Edson (1846–1888), and Otto Jacobi (1812–1901)—who portrayed Canadian scenery with varying degrees of naturalism, idealism, and romanticism. Examples ranged from Lake, North of Lake Superior, 1870, by Frederick Verner (1836–1928) to Mount Rundle, Canadian National Park, Banff, 1892, an albumen photograph of the Rocky Mountains by Alexander Henderson (1831–1913). Few, however, could equal Watson’s penetrating engagement with a particular geography—in his case the area in and around Doon, in Waterloo County—in an effort to understand it as deeply as possible.

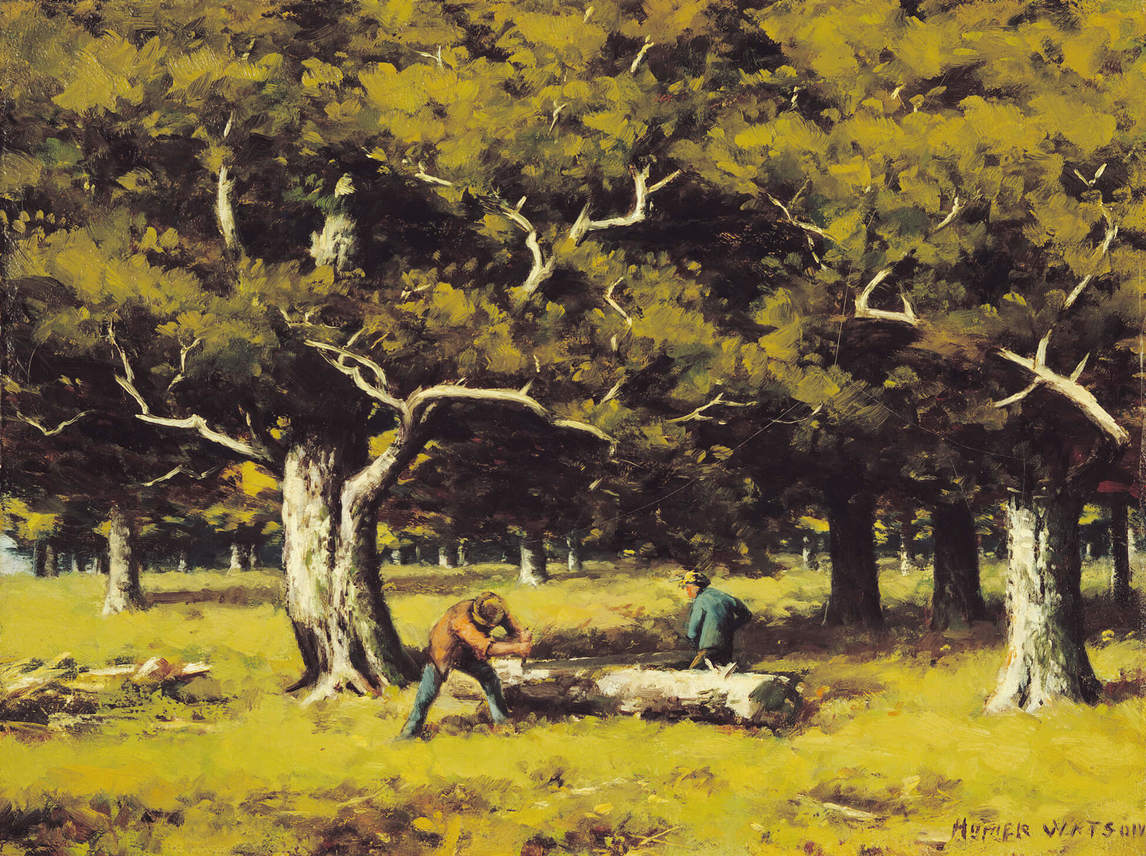

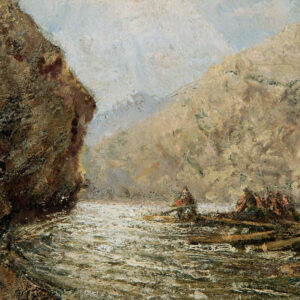

Although he often made art in places other than the Grand River Valley (The River Drivers, 1914 and 1925, for example, is set not on the Grand River but on the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia), the vast majority of Watson’s paintings are based to a significant extent on landscapes that he knew intimately. This was the case whether he was documenting the everyday reality of agricultural labour (Haymaking, Last Load, c.1880); commenting on the changing relationship between landscape and industry (The Pioneer Mill, 1880); evoking the grand sweep of the rolling landscape around Doon (A Cornfield, 1883); capturing the comfortable interaction between village inhabitants and the terrain in which they spent their lives (Log-cutting in the Woods, 1894; Nut Gatherers in the Forest, 1900); investing the local landscape with subjective mystery (Moonlit Stream, 1933); or in his later years painting in the open air (Moonlight, Waning Winter, 1924).

It is therefore unsurprising to read Watson’s many analyses of the relationship between a country’s artists and its landscapes. In his view, significant art was premised on its maker’s sense of “having roots in his native land and being a product of its soil.” Explaining his decision to return to Canada in 1890 after three years in Europe, he observed that as a Canadian artist in England he constantly risked unintentionally imitating English artists’ depictions of a landscape that was native to them but that was mere scenery to him. The English artist “goes along a smooth road, [whereas] here [in Canada] we are building roads, and that is more exciting.” Log-cutting in the Woods and The River Drivers, for example, were seen as quintessentially Canadian subjects. Although Watson rarely wrote about the work of other Canadian landscape painters, it is probable—based on his comments about his own art—that he would have expected them to portray their own environments with the kind of familiarity and understanding that he poured into such Grand River Valley images as The Pioneer Mill and Near the Close of a Stormy Day, 1884.

The Paradox of Representing Nature

Watson’s evocation of breadth of effect and mood produced a seeming paradox for his working method. Although he was conversant with—and sincerely devoted to—landscapes along the Grand River, his paintings were not faithful depictions of topographical reality. “I never make an exact copy from nature,” he told interviewers throughout his career.

When I want to paint a picture I make a number of studies of things I wish to put in the composition, and when I have these done, I sit down in my studio and paint as suits my fancy, using the sketches where I feel they suit. A picture . . . should be the sum-total of one’s experience.

He makes the same point in his unpublished essay “The Idealist versus the Realist,” in which he advocates for the need to recognize and balance two equally important phenomena: the underlying ideal of nature’s omnipresent power, and faithfulness to nature’s physical appearance.

This was true even in the late 1870s and the early 1880s, at the beginning of Watson’s career. Although canvases such as A Coming Storm in the Adirondacks, 1879; Grand River Landscape at Doon, c.1881; and Haymaking, Last Load, c.1880, are alive with detail, they are composite images rather than geographically precise records. As a University of Toronto professor, James Mavor, phrased it in an 1899 article about Watson:

When one who knows a landscape very thoroughly, finds himself observing it under a particular set of conditions, he will have present in his mind not only what he happens to have in his eye at the moment, but what he has seen before, and therefore a habit of close observation is necessarily linked to the habit of generalization.

The results were landscapes that Mavor described as having “more absolute truth to nature” than could be achieved from working only in the open air, “when changing moods and tones confuse the painter.”

Response to the Group of Seven

Watson had complicated reactions to Tom Thomson (1877–1917) and the artists who in 1920 formed the Group of Seven. He admired the seriousness that they brought to making art, but he had two significant concerns. One was stylistic. He viewed with skepticism the group’s brilliant colours and strongly design-based compositions: characteristics on full display in, for example, Sunset, Kempenfelt Bay, 1921, by Lawren Harris (1885–1970) and Mist Fantasy, Northland, 1922, by J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1972). He interpreted their style as too artificial, as being more grounded in design and borrowed style rather than being based in the artists’ personal connections to their subjects, and thus too detached from nature itself. “Lines, patterns, symbols are all very well,” he fretted in 1933. “They are necessary in a big design, but of themselves are useless or meaningless unless clothed with the authority a study and love of nature only can give.”

Beyond his worries about stylistic modernism, Watson resented suggestions that Thomson and the group produced art that was profoundly Canadian—but that he did not do the same. During the 1920s the group successfully promoted, to institutional and private collectors alike, a nationalist form of modernism that located the unique promise of Canada in the rugged, sparsely populated Precambrian Shield rather than in Watson’s familiar and settled landscapes.

Watson felt that his rural imagery was being ignored not only because it did not employ the stylistic traits of the Algonquin Park and Algoma artists, but also because it had, as its subject, landscapes that displayed the productive relationship between a location and the people who lived there. “I won’t be made to think that all of Canada is north country. Canada to me is where man lives . . . and advances his country by refining influences.” Thomson’s The Jack Pine, 1916–17, might be iconic, but for Watson pine trees were “no more Canadian than our elms, oaks or maple,” the deciduous trees that—as in Grand River Valley, c.1880—he spent his career painting with such devotion.

The Group of Seven spoke directly to evolving attitudes during the early twentieth century. Canada’s exploits during the First World War, and its promising future as an independent nation with vast natural resources and an expanding population, bolstered a belief that the country was coming into maturity at home and internationally. The group’s insistence on the uniqueness of the Canadian landscape fed an intensifying interest in articulating a specifically Canadian identity: one that could be expressed visually through physically challenging landscapes portrayed in dynamic modernist languages. Conversely, Watson clung to the local landscapes that he loved: a trait that endeared him to the likes of Hector Charlesworth (a conservative critic hostile to the brashness of the group), but that marked him as being out of touch with more forward-looking moods. And whereas the group’s bright palettes and decorative compositions offered visual drama, Watson’s forays into thick paint application and unusual and often muddy tones seemed more eccentric and isolated than modern.

In addition, the National Gallery of Canada’s Eric Brown (1877–1939) and Harry McCurry (1889–1964) offered vital support to the modernist members of the Group of Seven and the Beaver Hall Group, while showing dwindling interest in the twentieth-century work of Watson and the more and more conservative Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. After the First World War, Watson was thus outflanked by the group both thematically and optically in presenting a contemporary vision of twentieth-century Canada. The scope of his appeal contracted accordingly.

Environmentalism

It cannot be claimed that Watson’s visual aesthetics have been influential for other artists working over most of the past century. His pre-twentieth-century work fitted neatly into nineteenth-century approaches to landscape painting, but those ceased to be influential well before his death in 1936. The art that Watson made after about 1916 was idiosyncratic and tangential to the parameters of visual modernism and it exerted minimal influence on his contemporaries or on later artists. His lifelong commitment to environmentalism and to the sanctity of nature, however, echo strongly in twenty-first-century cultural attitudes.

Watson believed in the importance of people maintaining sustainable relationships with nature, a perspective that owed much to his self-identification as a grandson of pioneers. Yet he was also aware that those pioneers had not always respected natural resources and processes. He seems to have arrived at this knowledge principally by observing southern Ontario’s fast-changing landscapes, although his observations may have been supported by his extensive but poorly documented reading. Watson’s many drawings and paintings of rotting mills (including The Old Mill and Stream, 1879; The Pioneer Mill, 1880; and The Old Mill, 1886) can be read in part as nostalgic homages to displaced technologies. But they can also be understood as displaying the consequences of upsetting the balance between human needs and nature’s capacity to regenerate itself.

The narrator of one of Watson’s unpublished manuscripts recounts taking shelter in an abandoned mill that, like the structure in The Pioneer Mill, Watson based on his grandfather’s defunct sawmill in Doon. The speaker realizes that by the end of its heyday the mill had devoured all the trees in its vicinity. Starved of timber, the mill was then damaged by floods that previously would have been absorbed by the forest. Both the mill and the forest that once surrounded it died of human-inflicted wounds.

Environmental preservation was Watson’s justification when in 1913 he was instrumental in creating the Waterloo County Grand River Park Limited. He then served as president of the company, whose purpose was to buy and save a forty-acre stand of trees (Cressman’s Woods) near Doon. Cressman’s Woods as a site for human recreation and rejuvenation was a favourite theme in Watson’s art, and it appears as such in, for example, Woods in June, c.1910. In 1920 the tract’s mortgage holder demanded full payment, and Watson again came to the fore, raising the money needed to save the trees from logging. Cressman’s Woods continues to exist, and in 1944 it was renamed Homer Watson Park. As Watson wrote in a 1934 letter, “[Trees] have a hard time. I must save some to show what a beast man is sometimes.”

That beastliness continues. Ontario’s Environmental Commissioner reflected in 2010 that whereas a healthy ecosystem requires a minimum of 30 per cent forest cover (other experts prefer 40 to 50 per cent), the province’s southern forest cover averaged just 22 per cent overall and as low as 5 per cent in some areas. In addition, urban sprawl continues to devour farmland at an alarming rate. Approximately 18 per cent of Ontario’s Class I farmland (most of which is located in the south of the province) was lost in the twenty years from 1976 to 1996. Homer Watson’s environmental concerns have never been more relevant.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements