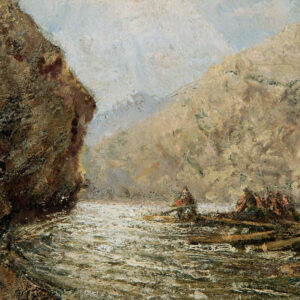

The Ranges (Camp at Sunrise) 1915

Homer Watson, The Ranges (Camp at Sunrise), 1915

Oil on canvas, 152 x 181 cm

Canadian War Museum, Ottawa

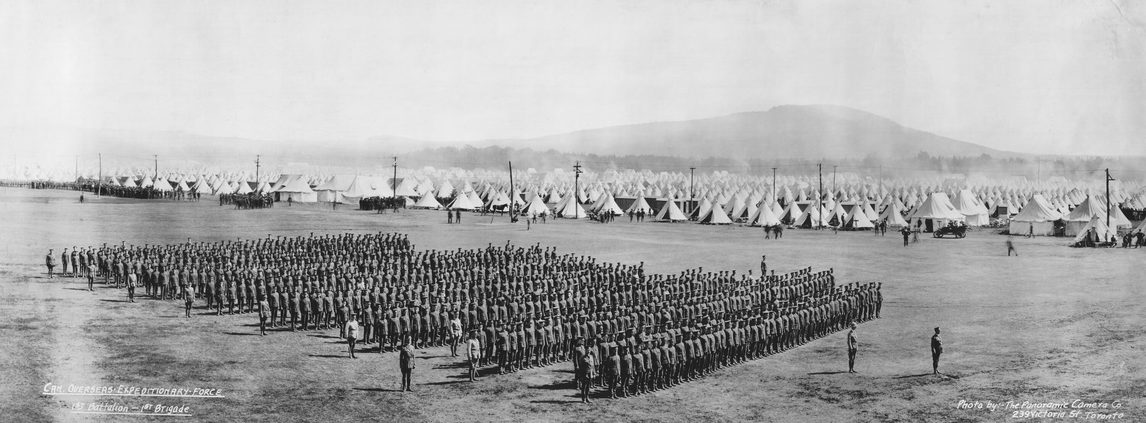

The painting today known as Camp at Sunrise was originally exhibited as The Ranges, one of only a handful of military-themed canvases that Watson painted during and immediately after the First World War. More than half of the painting shows a cloud-filled sky. Below that, another quarter of the canvas’s height consists of the colourfully painted Laurentians. These dominate a row of tiny human figures lying on the ground during rifle-firing practice, overseen by about a dozen officers.

Unlike several other Canadian artists—A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Frederick Varley (1881–1969), and David Milne (1881–1953), for example—who were commissioned to record military subjects in Europe, Watson (who was fifty-nine years old when the war began) did not leave Canada. Instead, in 1914 General Sam Hughes, Canada’s Minister of Militia, requested that Watson undertake paintings documenting the recruitment and training of the First Contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force at Camp Valcartier in Quebec. Watson was doubtful, but allowed himself to be persuaded that Valcartier offered a compelling landscape subject. By September 1915, after almost a year of work, he had produced three canvases, all set in the camp and all much larger than anything he had done before.

Some reviewers simply ignored the three paintings when they were seen at the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and at the Canadian Art Club in 1915. Others were overtly critical. Samuel Morgan-Powell, for example, dismissed them as showing inherently inartistic subjects more suited to General Hughes’s office hallways than to an art gallery. The reviewer for the Montreal Herald was more positive, but recognized that Watson had been rather an odd choice for the commission:

To a landscape painter, the straightness of line and mathematical precision in every detail so dear to the heart of the military commander do not commend themselves. . . . So Mr. Watson was obliged to compromise. He has painted the Valcartier of nature first, and the Valcartier of history secondly.

The Herald’s reviewer was right. The Ranges was clearly the work of someone who was at home with landscape painting but who had never before included more than six or seven people in a single image and who did not usually make human activity the dominant element in his art. As the Herald put it, Watson had depicted “temporary events in a permanent setting.” This was probably not exactly what Hughes, whose priority was to highlight the scale and interest of troop activities, had envisioned.

Toward the end of the war Watson accepted another military-themed commission, this one from Commander J.K.L. Ross, the son of his greatest patron, James Ross. On that occasion, though, he ventured into symbolism, possibly reflecting his growing interest in spiritualism following his wife’s death in 1918. One of the paintings, Passage to the Unknown, 1918–20, deals with the beginning of the war: a road transforms into a sky bridge over which soldiers could pass on their way to serving in Europe. In the other painting, Out of the Pit, 1919, Watson suggests hope for the future at the end of the war by juxtaposing a burning castle, a rainbow, and a bright background. Whereas The Ranges had its defenders, Passage to the Unknown seems to have pleased almost no one, and was possibly destroyed by Ross himself.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements