Homer Ransford Watson (1855–1936) has been characterized as someone who, in the nineteenth century, first portrayed the surrounding landscape as specifically Canadian, rather than as a pastiche of European influences. Although Watson had almost no formal training, by his mid-twenties he was well known and admired by Canadian collectors and critics, his rural landscape paintings making him one of the central figures in Canadian art from the 1880s until the First World War. His art documents the centrality of the pioneer legacy to Ontario’s sense of historical identity and crucially emphasizes the importance of environmentalist approaches to the landscape.

Early Years and Artistic Beginnings

Homer Watson’s birthplace, built c.1844 by his grandfather James Watson, one of the first settlers in the area. Photograph taken in 1866, photographer unknown.

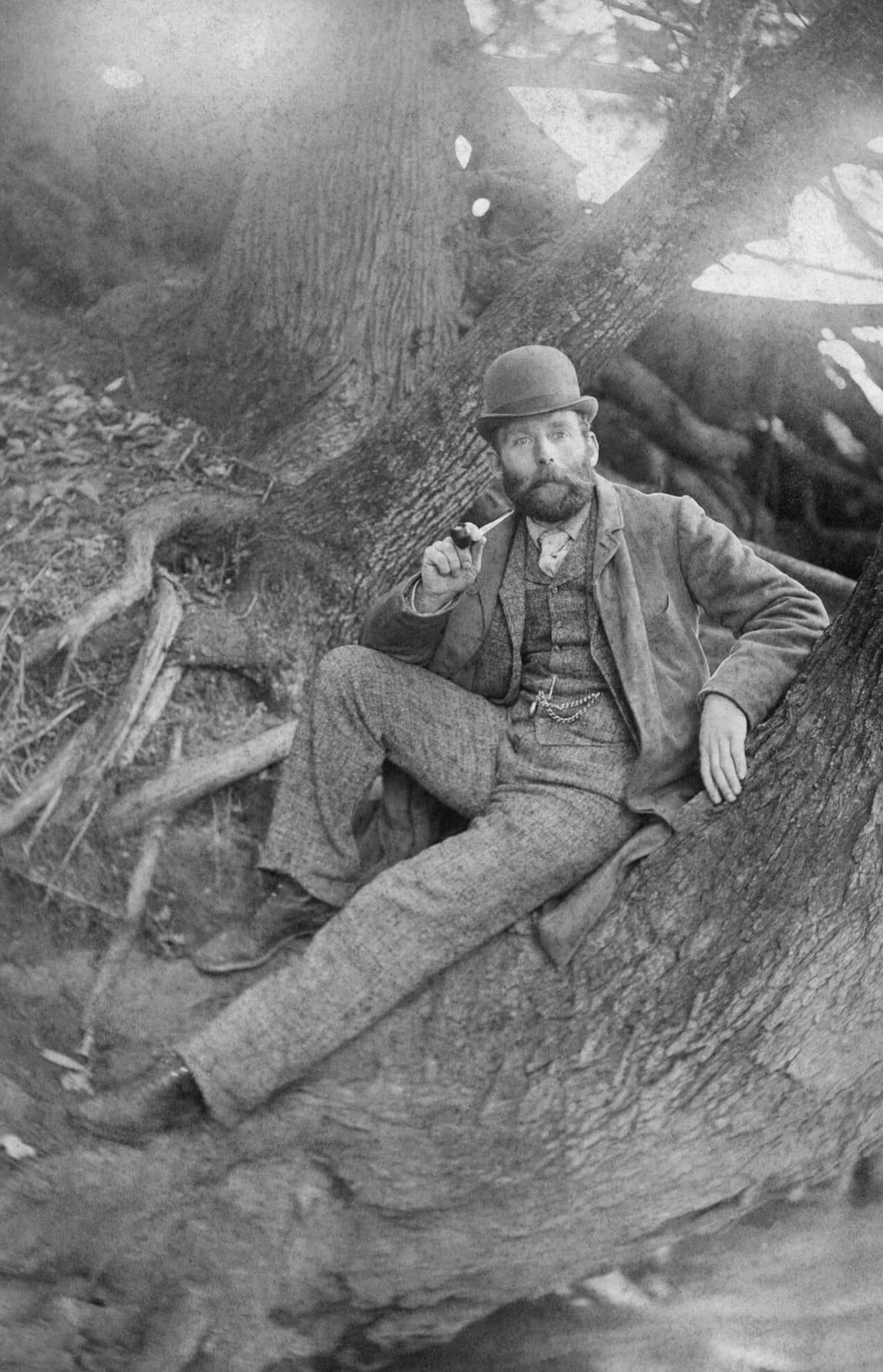

Homer Watson’s birthplace, built c.1844 by his grandfather James Watson, one of the first settlers in the area. Photograph taken in 1866, photographer unknown.Watson was born on January 14, 1855, in Doon, today a suburb of Kitchener but then a separate village on the Grand River in southern Ontario’s Waterloo County. Doon had been founded just twenty-one years before his birth and when he was in his mid-teens had a population of about 150. The second of five children of Ransford and Susan Mohr Watson, Homer was related through his mother to the Mennonite German settlers who had arrived in the area in the early nineteenth century. His paternal grandfather had emigrated from New York State soon thereafter. Throughout his life Watson remained conscious of being a descendant of pioneers.

When Watson’s father died in 1861, he left a widow and four (soon to be five) young children, including six-year-old Homer. A short-lived attempt by an uncle to maintain the family sawmill and woollen mill came to naught, and the household was forced to rely largely on Susan Watson’s work as a seamstress. In 1867 Homer’s older brother, Jude, was killed while working at a local brickyard—an accident that twelve-year-old Homer witnessed. It is usually thought that Watson abandoned his formal education around this time, although this is not certain. Taken together, the deaths of Ransford in 1861 and of Jude in 1867 were crucial to Homer’s transition into an early maturity.

Watson’s interest in drawing was supported by gifts from family members: a set of watercolours when he was eleven years old, and his first oil paints four years later. In addition, William Biggs, a schoolteacher in the neighbouring village of Breslau, was an amateur watercolourist who, according to the artist’s first biographer, “gave Watson what assistance he could.” Otherwise, Watson’s most formative childhood lessons consisted of emulating the etching and woodcut illustrations in the books and journals in his family’s library. These included periodicals such as Penny Magazine (London) and probably The Aldine (New York) as well as at least one book illustrated by the nineteenth-century artist Gustave Doré (1832–1883).

Watson’s earliest competent work included drawings based on novels and poetry by Charles Dickens (Quilp and Sampson Brass in the Old Curiosity Shop, late 1860s to early 1870s), Lord Byron, and others, along with a few portraits and figure paintings such as The Swollen Creek, c.1870. By the end of his teens, however, he had all but abandoned these subjects. Watson had already begun to successfully submit art for display at local fairs before he visited Toronto for the first time in 1872. There he met and was encouraged by the landscape painter Thomas Mower Martin (1838–1934). Two years later he received an advance on his inheritance and used it to return to Toronto for several months, copying paintings at the city’s Normal School (an institution that trained high school graduates to be teachers) and occupying workspace at the Notman-Fraser photographic studio. There he appears to have attracted the interest of Lucius O’Brien (1832–1899), vice-president of the recently formed Ontario Society of Artists and one of Canada’s pre-eminent landscape painters.

New York Travel and Early Fame

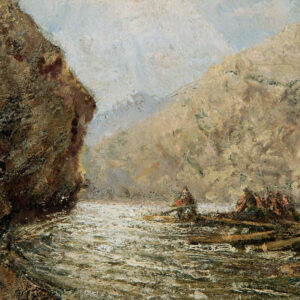

Emboldened, Watson travelled in New York State from 1875 (possibly 1876) until late in 1877. Almost nothing is known about his time there, except that he worked in the Adirondack Mountains and along the Susquehanna, Mohawk, and Hudson rivers (see, for example, Susquehanna Valley, c.1877), and that he received limited instruction from an unnamed painter. Various sources have identified that painter as George Inness (1825–1894), one of the most ambitious, influential, and successful American landscape artists of the second half of the nineteenth century, although in later life Watson stated that they had not in fact met. However, Watson’s resulting work suggests that he likely saw canvases by Inness and by the Hudson River School artists, especially as his itinerary covered territory that was closely associated with the latter group.

The lush richness of Inness and of the Hudson River School is recalled in Watson’s penchant for vivid atmospheric effects as well as in his predilection for the visceral experience of being immersed in the landscape. On the Mohawk River, 1878, for example, achieves these ends by incorporating a palpable atmosphere and by employing an evocative composition that moves from a relatively dark, detailed foreground to the refreshing airiness of a distant mountain cliff. His American sojourn clearly helped Watson develop his abilities as a landscape painter, but he longed for the southern Ontario scenery in which he had grown up and which was to remain a touchstone for his art throughout his career. After many months in New York, he returned to his beloved Doon to paint “with faith, ignorance and delight.”

Watson quickly began to build a reputation. He was elected an associate draftsman/designer member of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) in April 1878 and first exhibited with the society the following month. The Toronto Evening Telegram praised his paintings for “the naturalness of the details, the careful finish, and the softness of the harmony of the colours.” Watson changed his OSA membership status from draftsman/designer to painter soon thereafter, and contributed to the society’s December 1878 and May 1879 exhibitions. Press reaction to the newcomer was again favourable, with the Toronto Globe remarking that he was “very rapidly coming to the front in the estimation both of the public and his fellow-artists.” It was an auspicious beginning, especially as some of the exhibited paintings were more than a square metre in size: impressively large for an untrained novice.

Striking though Watson’s first appearances at the OSA were, a pivotal moment of his early career came in Ottawa in 1880 at the inaugural exhibition of the Canadian Academy of Arts (soon renamed the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, or RCA). Watson’s entry, The Pioneer Mill, 1880, was purchased for $300 by the Marquis of Lorne, Canada’s governor general, as a gift for Lorne’s mother-in-law, Queen Victoria. The purchase made Watson’s reputation, facilitating his election to associate membership in the academy in 1880 and promotion to full academician in April 1882. Just two months after Lorne’s purchase, the Ontario government acquired Watson’s On the Susquehanna, date and location now unknown. The artist’s career had been solidly launched.

The founding of the Canadian Academy in 1880, and the tremendous impact that the governor general’s acquisition of The Pioneer Mill had in kick-starting Watson’s career, testified to the deeply British nature of cultural life in Canada, especially English Canada, in the decades prior to the First World War. What little art training existed (through the academy, the Ontario Society of Artists, and the Art Association of Montreal) mirrored traditional European academic techniques, just as the structure and goals of the Canadian Academy largely paralleled those of Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts. The late nineteenth century saw some emerging debate about distinctively Canadian themes in art, but the cultural infrastructures that developed alongside the country’s growing economy tended overwhelmingly to be grounded in conservative European prototypes—hence the great importance for Watson’s career of the governor general’s purchase of The Pioneer Mill from the 1880 Canadian Academy exhibition.

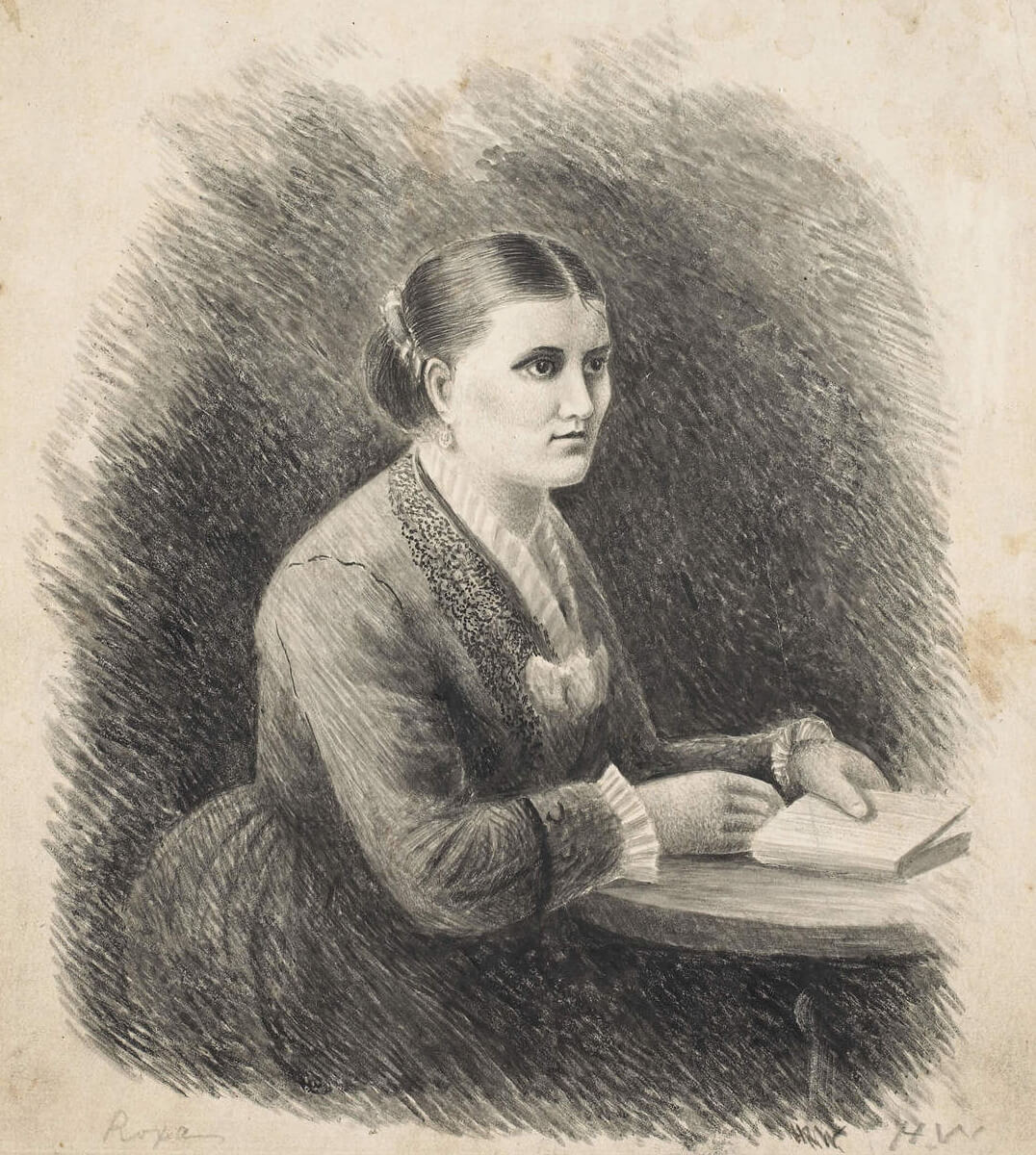

On a practical level, Watson—buoyed artistically, financially, and socially by Lorne’s largesse—was able to marry his long-time fiancée, Roxanna (“Roxa” or “Roxy”) Bechtel, on January 1, 1881. Their only child, a son, died at birth in 1882, but twenty-five years later, in 1907, they adopted an orphan named Mary. The young couple lived with Watson’s mother and his sister, Phoebe, for a few months before moving into the upper part of a house built by Adam Ferrie, one of the most important—and the most economically successful—of Doon’s founders. Watson was able to buy the entire house the following year and, except for occasional trips abroad, would live there for the rest of his long life. (The building later became the home of the Doon School of Fine Arts, 1948–66, and exists today as a museum: Homer Watson House & Gallery.) The funds for the purchase came from two more sales to the Marquis of Lorne: large landscapes from the RCA’s second (1881) exhibition. Lorne gifted one painting, The Last of the Drouth (The Last Day of the Drought), 1881, again to Queen Victoria, and retained the other, April Day, c.1881, for himself. Watson remained friendly with Lorne for years to come. The publicity he gained from this vice-regal patronage remained a cornerstone of his reputation throughout his career.

Oscar Wilde and “the Canadian Constable”

Another public figure made a major impact on Homer Watson’s career: Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). In early 1882, the twenty-seven-year-old Wilde (he had been born three months before Watson) undertook what developed into a year-long lecture tour of the United States and Canada. He addressed audiences on the subjects of Aestheticism and the importance of beauty in daily life. Wilde had yet to establish a reputation as an author, and his mannerisms and exotic clothing provoked ridicule, but the tour was a commercial success. By the time he arrived in Toronto in the spring of 1885 he was a celebrity.

Wilde did more than lecture; he also promoted North American artists and writers in whom he became interested during his tour. On May 25, while viewing the Ontario Society of Artists annual exhibition, he was struck by Watson’s painting Flitting Shadows, c.1881–82. (No description of Flitting Shadows survives, but it may have corresponded to On the River at Doon, 1885, in theme, atmosphere, and mood.) Drawing parallels with European landscape artists, Wilde—speaking to newspaper reporters while he stood in front of the painting—described Watson as “the Canadian Constable,” referring to the English painter John Constable (1776–1837), with whose work Watson’s does have similarities. Wilde repeated his praise during a lecture at Toronto’s Grand Opera House that evening. For the rest of his career Watson would bear the Constable epithet, along with the subsequent Wilde quip that he was “Barbizon without ever having seen Barbizon,” referring to the French artists who had worked in and around the village of that name. Constable and the Barbizon painters were highly popular with North American and European audiences, and Wilde’s comments gave Watson’s career another boost. The two men did not meet in person until Watson’s first sojourn in Britain a few years later. In the meantime, however, spurred by his admiration of Flitting Shadows, Wilde commissioned Watson to make paintings for himself and for two American acquaintances.

In later life Watson often resented Wilde’s comparisons because—as he frequently insisted—it was not until his first trip to Europe, at the end of the 1880s, that he actually saw paintings by Constable and the Barbizon artists. There was, however, justice in Wilde’s remarks. In fact, even before his visit to the OSA exhibition, the Toronto Mail had described Flitting Shadows as recalling Constable’s landscapes.

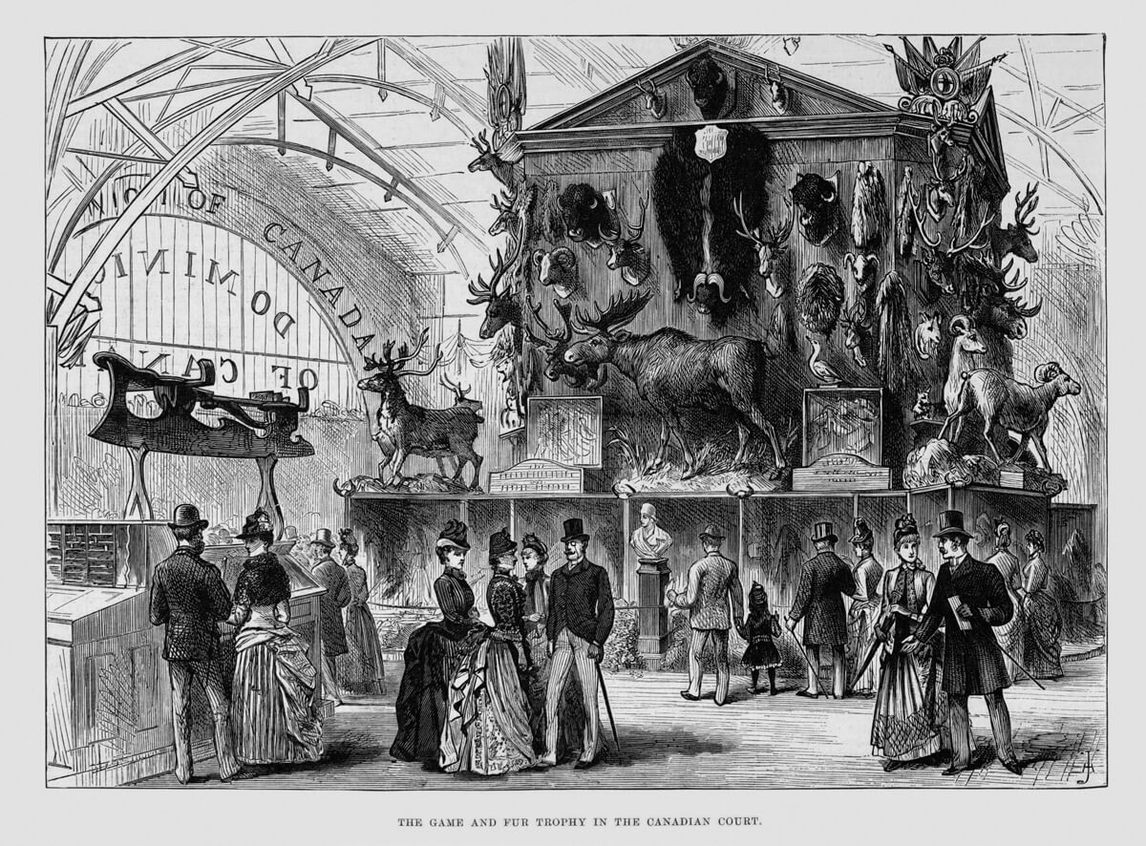

Europe, 1887–90

In 1886 five Watson paintings were included in the massive Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London, which showcased a vast array of objects from across the British Empire. The exhibition included a Watson loaned by the Marquis of Lorne, River Torrent, early 1880s, and A Coming Storm in the Adirondacks, 1879, owned by the Montreal banker George Hague. Watson won a bronze medal in this display, which marked his first inclusion in an exhibition outside Canada. That recognition may well have precipitated his decision to travel to Britain in the summer of 1887.

Watson and Roxa originally intended to remain there for about a year; however, they delayed their return to give Watson time to solidify a European reputation. The Toronto art dealer John Payne urged him not to return to Canada until he was known abroad because, Payne logically argued, North American buyers were interested only in artists who had reputations in Europe. The Watsons followed Payne’s advice and stayed in Britain for three years, until the summer of 1890, although their first months there were discouraging. “I do not know whether it did me any good,” Watson wrote later. “But I had a feast of study into the old masters which knocked me out as it were . . . and showed me I did not know anything. While the feeling lasted I could not do any good work.”

Watson’s frustration was exacerbated by the difficulty of gaining a toehold in British galleries and exhibitions. In search of success, he and Roxa settled with relatives in Maidenhead. From there they moved to London, which, although Roxa admitted that her husband “got a certain amount of good out of it,” she found to be an “abominable” city: “so very dirty and foggy that [Homer] got some of it into his work.” Beginning in the autumn of 1889, in attempts to achieve a balance between affordability, the familiarity of rural life (always important to Watson), and access to art and exhibitions, the couple travelled to Scotland, setting up residence on the southeast coast in the village of Pittenweem. In Scotland they became friendly with painter James Kerr-Lawson (1862–1939), whom they had first met in Canada, and Caterina Muir (1860–1952), whose family was friendly with Kerr-Lawson. The Watsons also took advantage of their time in the U.K. to make two short trips to Paris.

After a shaky beginning in Britain, Watson’s prospects began to improve. He finally met Wilde in person and, more important, became friendly with a number of artists, including James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), E.J. Gregory (1850–1909), and George Clausen (1852–1944). Four decades later, when asked by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa to describe his training, Watson answered that he was “[s]elf taught but for some months was associated with Clausen & Gregory in England.” Clausen, whose art and personality Watson admired, was a highly regarded portrayer of rural life and landscapes (as in Winter Work, 1883–84).

Clausen was also sufficiently impressed by Watson’s black and white drawings that he convinced him to try translating his draftsmanship into etching. The results were prints of The Pioneer Mill, 1880, and five smaller landscapes, the only etchings Watson ever made. The Pioneer Mill etching as printed by Watson exists in three states (versions), with the third apparently produced in an edition of fifty. Even with that small total, however, sales in Toronto were disappointing, nor is there any record of copies having been sent to Montreal or elsewhere for sale. The reasons for this failure were multiple, and included the competitive availability of cheap prints imported from abroad, John Payne’s inexperience as a print dealer, and a general lack of Canadian interest in supporting the international etching revival.

Watson’s career breakthrough in Britain finally came in the spring of 1889, the year before he printed The Pioneer Mill. In that year he had work admitted to two important annual summer shows. In March The Mill in the Ravine, 1889, was accepted at the recently established and decidedly upscale New Gallery in London. Roxa, with democratic disdain, described the New Gallery as having a clientele of “Lords, Dukes, Duchesses, Countesses and all the other swells that this country is rotten with.” The Mill in the Ravine (location unknown, but with similarities to the surviving A Hillside Gorge, 1889) was bought on the private view day by Alexander Young, a leading collector of Barbizon painting. So began Watson’s ongoing relationship with the New Gallery, where he exhibited again in 1890, 1895, 1897, and 1901.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1889, Watson’s The Village by the Sea, 1887–89, was approved by the jury for the Royal Academy of Arts summer exhibition in London. Roxa had been doubtful. “There are generally about seven thousand pictures sent in,” she wrote to her husband’s sister and mother, “and only about two thousand hung.” She also underestimated her husband’s chances because she feared that his efforts to incorporate new elements into his work had “carried the gray business to extremes as you know he is likely to do when he gets a new idea.” The painting was not only accepted for exhibition but given a good position in the dense floor-to-ceiling hanging.

By 1890, homesick for more familiar landscapes, Watson was ready to return to Doon. “The whole of the old world is permeated with [art],” he wrote. “There is no possibility scarcely of doing anything new. . . . I have come to the conclusion that I would sooner paint at home.”

Market Success

It is impossible to confirm biographers’ claims about the number and dates of Watson’s exhibitions during his seven trips to Britain in 1887–90, 1891, 1897, 1898–99, 1901, 1902, and 1912. However, sufficient information survives to verify his involvement in events organized by the New English Art Club (his entrée there seems to have been thanks to Oscar Wilde), the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts, the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, and miscellaneous other groups and events in London, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Bristol, Liverpool, and elsewhere. Thanks to the intercession of the Marquis of Lorne, Watson also had work seen at the prestigious Goupil Gallery in London in 1888, a relationship that continued into the twentieth century. He moreover held a solo showing of thirty paintings at London’s Dowdeswell Gallery in 1899, organized, it appears, at the behest of the British critic David Croal Thomson and of the Montrealer James Ross, Watson’s most supportive Canadian patron. Finally, by 1901 Watson had arranged for E.J. van Wisselingh of the Dutch Gallery to handle his work in London, although it is unclear how long that relationship lasted.

The fit between these two men was a natural one. Van Wisselingh specialized in Barbizon art as well as in the Hague School painters, whose art was indebted to that of their Barbizon counterparts. Watson esteemed van Wisselingh precisely because “[h]e is of the order that will not have about him anything he is not in sympathy with [and] so he is far removed from being a mere trader.” It may well have been through van Wisselingh, who shared his London business with Daniel Cottier, that Watson struck a professional relationship with Cottier’s New York gallery, where he had shows in 1899 and 1906.

Also in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Watson participated in the Canadian sections of such extravaganzas as the World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago, 1893), the Pan-American Exposition (Buffalo, 1901), the Glasgow International Exposition (1901), and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis, 1904), winning a bronze medal in St. Louis, a silver in Buffalo, and a gold in Chicago.

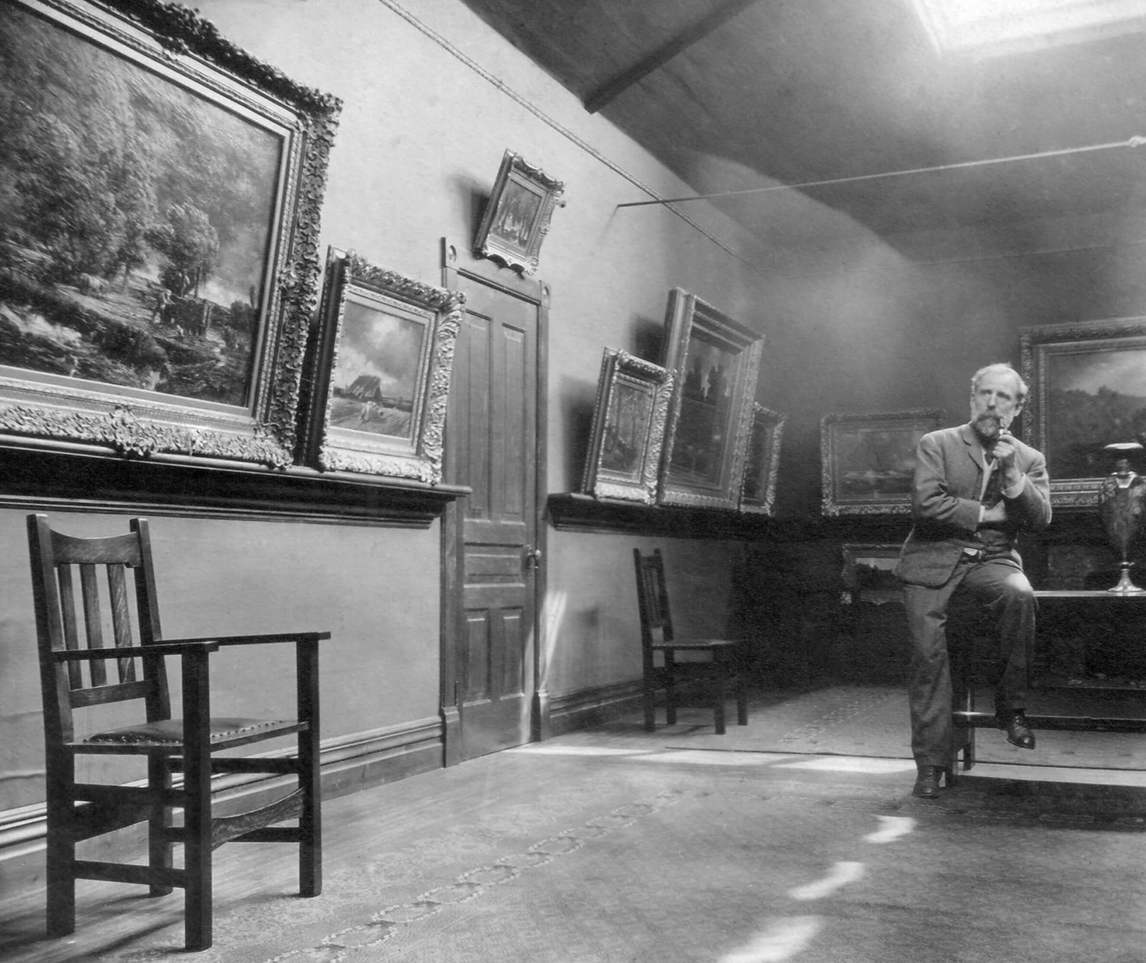

But Watson’s career was above all in Canada. The principal subjects of his art never ceased to be the landscapes in and around Doon, although he occasionally painted in Nova Scotia (he had first done so in 1882, as his patron James Ross had a property and considerable investments on Cape Breton Island), on Île d’Orléans in Quebec (Down in the Laurentides, 1882; Sunlit Village, 1884) with Horatio Walker (1858–1938), as well as elsewhere in Canada and the United States. In 1893 he built a painting studio extension onto his house, and in 1906 added a gallery to which for the next thirty years he welcomed potential buyers.

Watson, a committed environmentalist, was the key organizer and president of the Waterloo County Grand River Park Limited, which saved Cressman’s Woods (today, Homer Watson Park) near the artist’s home. His environmental interests paralleled his certainty that artists who lacked a sense of living connection to the landscapes around them risked falling back on impersonal formulas. He explored this belief in a series of half-autobiographical and half-fictional drafts for manuscripts that elucidated his philosophy of landscape painting but that went unpublished until well after his death.

Watson’s conviction about the importance of strong relationships between artists and landscape also coalesced with the Barbizon and Hague School sympathies of his main audience. In Montreal, beginning in the 1880s, Charles Porteous, an important collector, patron, and promoter, relied on those sympathies when he organized displays of Watson’s art. As a result, Montreal—home to millionaires such as businessman James Ross, banker and financier R.B. Angus (who acquired, among other things, Flitting Shadows, c.1881–82, the painting so admired by Oscar Wilde), railway magnates Donald Smith (Lord Strathcona) and William Van Horne, and businessman and future senator George Drummond—was Watson’s most lucrative market. When the influential Art Journal (London) published a four-page article on Watson in 1899, five of the seven reproductions were of paintings owned by Montreal collectors.

Elsewhere, the market tended to be less wealthy. While Watson was in Europe from 1887 to 1890 his Toronto affairs were handled by two dealers, James Spooner and (more satisfactorily) John Payne, with Payne paying Watson a monthly allowance of fifty dollars, beginning in May 1888. The Watsons badly needed that money. However, both Spooner and Payne frequently lamented their Toronto business difficulties. “Nothing doing in art matters,” moaned Spooner to Watson in 1885, and three years later Payne informed the artist that “the people here are not buying, and do not appreciate anything that is not cheap.” Payne in particular was able to sell to such prominent Torontonians as the businessman Edmund (E.B.) Osler, but more often he spent his time advising Watson to paint smaller, less expensive landscapes, and recommended changes in colour, composition, detail, and theme to make the paintings more saleable. Like other artists, Watson saw his success hampered by Canada’s—and especially Toronto’s—paucity of collectors, a reality repeatedly bemoaned by John Payne. Moreover, the Art Museum of Toronto (today the Art Gallery of Ontario) was not founded until 1900, and for many years after that date relied heavily on donations of artworks. Similarly, although the Art Association of Montreal (today the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) acquired Watson’s impressive early canvas A Coming Storm in the Adirondacks, 1879, in 1887, it was as a gift rather than a purchase.

Elder Statesman

In 1907 Watson agreed to become the first president of the Canadian Art Club (CAC), a private exhibiting society founded in that year and dedicated to promoting contemporary Canadian art. Although not temperamentally inclined toward administration, Watson shared the other members’ annoyance that too many Canadian collectors of recent European painting and sculpture were unwilling to invest in Canadian art and artists. In March 1907, for example, he complained to another CAC member, Edmund Morris (1871–1913), that Frank Heaton, the owner of Montreal’s important W. Scott & Sons gallery, had “[h]is [money] in Dutch stuff and he will not look at our things. . . . We must show that our things are so much better than most of it that people will tire of being gulled.” Watson was referring to paintings such as The Cowherd, c.1879, by Anton Mauve (1838–1888). Mauve’s subject matter and quiet tonality were typical of the extremely popular work of the Hague School artists.

Watson remained the club’s president until 1913 and participated generously in all nine of its exhibitions. In 1907 he—like the other founding members of the CAC—had resigned from the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA), an organization the club saw as mounting uninspired annual exhibitions from which the Ontario government purchased work for the provincial art collection. Upon the dissolution of the CAC in 1915, however, Watson was delighted to learn that his OSA membership had been reinstated by a unanimous vote. “The club we formed did its work according to its lights, and died a natural death having done this,” he wrote to the OSA’s president. “In the meantime the Society has gone ahead with strength[,] giving way to progressive ideas as these came forward, the product of an earnest striving for larger ways of looking at and studying the truth of nature.”

In 1918 Watson was elected president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), where he replaced the ailing William Brymner (1855–1925). He had served as the RCA’s vice-president since November 1914, and occupied the presidency until his growing deafness drove him to resign from the job in 1922. His tenure coincided with escalating tension between several of the more conservative members of the RCA and Eric Brown (1877–1939), director of the National Gallery of Canada. To the anger of several academicians and associate members, Brown actively supported modernist artists in general and, in particular, the members of what in 1920 became the Group of Seven: artists toward whose work Watson was usually ambivalent.

Things exploded soon after Watson left office. The National Gallery assumed responsibility for selecting jury members for the Canadian section of the 1924 British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park in London. In the past the task of organizing international exhibitions of Canadian art had fallen to the RCA, and the academy was furious about the change. In 1923 its executive and many of its other members decided to boycott the 1924 exhibition. The decision was announced in a letter published in newspapers, above the signatures of thirty-one members, including recently retired president Homer Watson. He insisted, however, that he had not signed. Watson was included in the 1924 Wembley display and its successor the following year, showing Nut Gatherers in the Forest, 1900, in 1924 and Flamboro Woodland (date and location unknown) in 1925. He noted that although he felt that the artists most favoured by the National Gallery’s jury tended to have only “tolerant contempt” for their usually less modernist elders, he doubted that the grievance expressed in the letter would stand up to investigation.

The 1924 Wembley exhibition would become a defining event in Canadian art history, with British critics reserving most of their praise for the work of the modernists: Tom Thomson (1877–1917) and members of the Group of Seven, and Montreal artists such as Randolph Hewton (1888–1960), Mabel May (1877–1971), Kathleen Morris (1893–1986), and other members of the Beaver Hall Group. Watson recognized the exhibition’s importance: “At any time now we of the old guard can drop out and never [be] missed,” he lamented in a letter to Eric Brown. By the mid-1920s the RCA was dominated by senior artists who continued to work in outdated nineteenth-century aesthetics and who spluttered with rage at what they took to be the incompetence of younger, avowedly modernist artists. From 1926 to 1932 the RCA and the National Gallery descended into ever more acrimonious bickering that threw the academy into a weakened position. It never recovered its former status as an exponent of progressive art in Canada.

This must have been deeply saddening for Watson. Even so, he had accomplished good work as president, implementing a new constitution and putting the RCA on more stable financial footing after cutbacks during the First World War. As an artist, too, he remained active and admired, albeit by a smaller audience than he had enjoyed prior to the war. Just four years before the 1924 Wembley exhibition, where British critics lauded Canadian modernists as the future of Canadian art, The Jenkins Art Gallery in Toronto held a hearteningly successful show and sale of Watson’s work, paintings from the previous approximately thirteen years that, until then, Watson had reserved in his private Doon gallery. During that time he had moved from landscapes characterized by dark, chromatically restricted hues to views in which lighter but often puzzling reddish tonalities were increasingly present. Some one hundred paintings were shown at The Jenkins Art Gallery, and half of them found purchasers.

Last Years and Travel West

Watson’s election to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA) presidency at the beginning of April 1918 had been a flattering testament to his stature as a senior artist who managed to stay on good terms with almost everyone. It was also an acknowledgement of his unwavering commitment to the academy; he contributed to all but two of its fifty-seven annual exhibitions from 1880 until the year of his death.

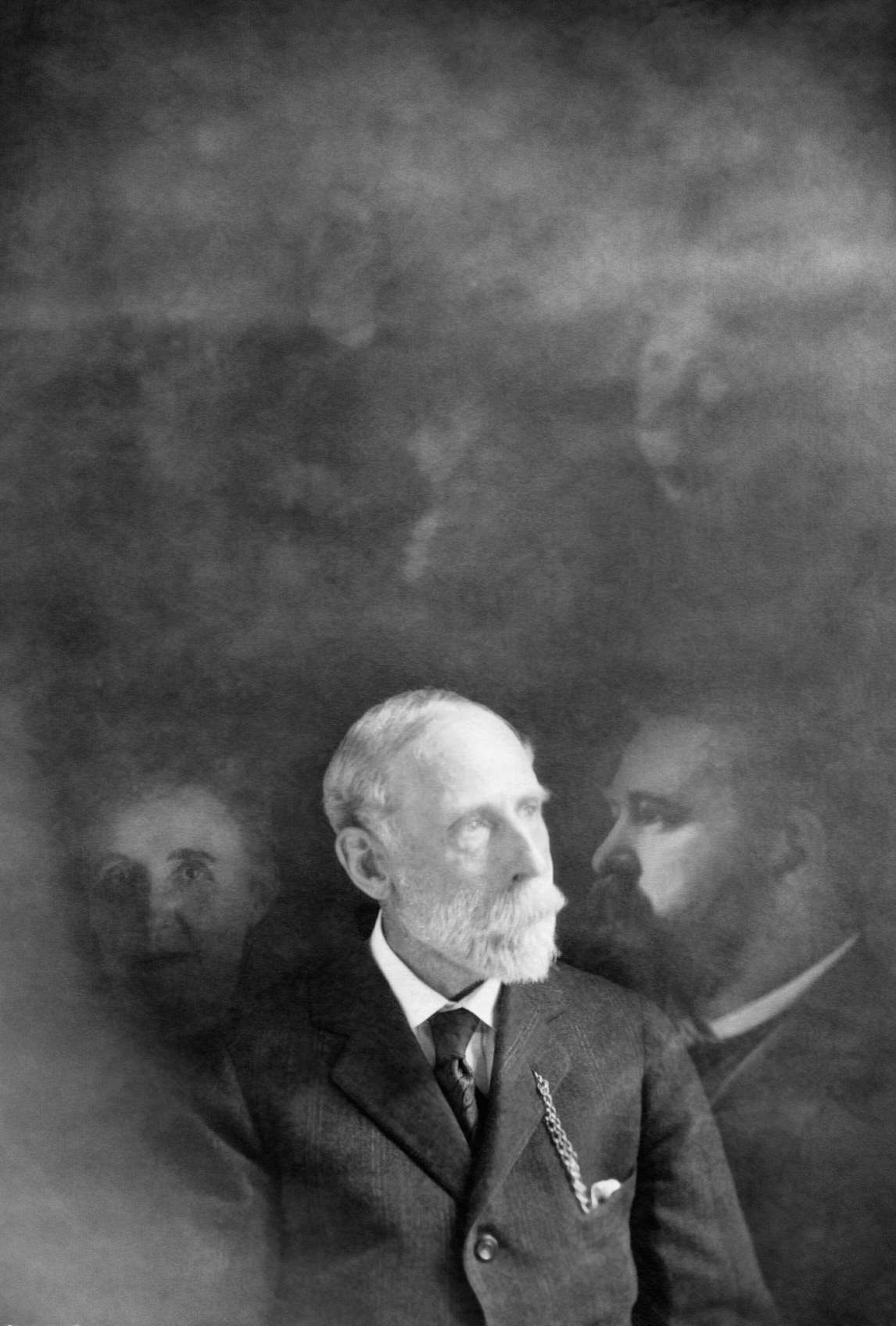

The election could not, however, console Watson following the death of his wife four months before, in January 1918. He had never been religious, but he had long-standing pantheistic beliefs about connections between nature and humanity: beliefs that underpinned his art from that time onward. As early as 1879, he had been sufficiently intrigued by ideas about the afterlife and the occult that he made the first of what appear to have been several trips from Doon to the hamlet of Lily Dale in southwestern New York State, where visitors interested in exploring spiritualism in a natural setting gathered at the recently incorporated Cassadaga Lake Free Association.

Following Roxa’s death, he turned to the Bible for assurance that his wife’s spiritual life continued after the death of her body. At this time he also became fascinated by seances and spirit photography, which he pursued through the Ontario Society of Psychic Research in Kitchener. Despite his newfound interest in the Bible, however, Watson’s spiritualist longings continued to be expressed through his search for suggestions of the mystical within the natural environment. This interest was manifested in the intense subjectivity of his late landscape paintings, in which he increasingly sacrificed optical veracity and detail to unnatural colour and heavy brushwork. Strict faithfulness to his motifs had never been crucial to Watson. Even in his early canvases he had combined multiple on-site sketches into compositions in which visual veracity was adjusted and compromised for the sake of order, liveliness, and mood. Much of The Pioneer Mill, 1880, for example, is based on a Doon landscape, but the image also includes a line of vertical cliffs that were not part of the actual locale. In his late landscapes, however, Watson increased the image’s subjective weight, often by favouring scenes of dusk and darkness: transitional and mysterious times of day. All these elements came together in, for example, such powerfully moody and personal landscapes as Moonlit Stream and Evening Moonrise, both 1933.

By 1921, sustained by his sister’s emotional support and housekeeping, Watson was beginning to recover from his grief and turning his attention back to making art. In that year he visited the Rocky Mountains for the first time. He made the trip at least twice more, in 1929 and 1933, during those years travelling as far as the Pacific coast. In 1919 F.M. Bell-Smith (1846–1923) had offered incitement for such a trip. “Have you ever been through the Rockies?” he asked Watson. “I would be much interested to see what you could fish out of those impossible subjects. I find it very difficult to get above facts. The facts are terribly assertive.” The subject seemed an unlikely one for an artist dedicated to the local landscapes of the Grand River, with their familiar human history. But the mountains—in Near Twilight, B.C., c.1934, for example—proved highly attractive to Watson despite his general advice to artists to avoid stupendous scenery in which they would feel dominated and irrelevant.

Bolstered by his 1921 trip west, weary of the demands of arts administration, and afflicted with intensifying deafness, Watson embarked on the final years of his career. The acquisition of his first automobile in 1923 enabled Watson to carry his painting equipment with him on far-ranging painting trips. These were, however, difficult years. Beginning in 1927, several heart attacks progressively limited his ability to work. In especially poor health from 1929 onward, he wrote in 1933 that his “little grinding mill clatters to pieces with my little strains.” Health problems were compounded by financial disaster when the collapse of the stock market in October 1929 devastated the stocks and bonds in which Watson had invested his considerable earnings. He eventually saw no option but to transfer title of his current and future paintings to the Waterloo Trust and Savings Company as collateral for a monthly allowance. At the time of his death, the company possessed 460 of his pictures.

At the same time as his savings were almost entirely wiped out, Watson experienced a substantial decline in demand for his paintings. The Depression lingered well into the 1930s, severely hindering the purchasing power of many of Watson’s previous customers. Plus, most of his wealthiest patrons had died before the Depression even occurred.

In any case, by the 1920s Watson was out of step with contemporary developments in art. The modernist Group of Seven in Toronto and the Beaver Hall Group in Montreal were both founded in 1920, and the Group of Seven in particular mounted an effective campaign to establish its own brand of modernism at the heart of Canadian art. Watson recognized the changing tastes and unsuccessfully attempted to discourage a 1930 solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto. Sales from the exhibition were modest at best. He apparently believed that he was making a good attempt to update his style by adopting a colour scheme dominated by shades of pink and purple, employing substantial impasto, and—thanks to his automobile—shifting to plein air painting and very little studio work. The results, unfortunately, attracted few converts to Watson’s art and alienated many of his erstwhile supporters.

The RCA reviewed Watson’s grave financial situation at its council meeting on May 11, 1936. His old friend Wyly Grier (1862–1957) followed up by writing to Watson’s sister, assuring her that her brother “need never fear destitution. The Academy has available bonds which have been legally declared available for helping members in difficulty and love for Homer will do the rest.” But it was too late. Watson, whose acute deafness and heart problems had transformed him into “the hermit of Doon,” died in his native village on May 30. He was eighty-one years old. An honorary Doctor of Laws degree that the University of Western Ontario (now Western University) had intended to bestow upon him in person was instead awarded posthumously. The prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, who as a boy had met Watson in 1882, and who admired the artist and shared his interest in the occult, devoted a paragraph in his diary to the death. Watson, he concluded, was “one of the noblest souls I have ever known. A man I really and truly loved, a great gentleman & a great artist.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements