After Helen McNicoll’s death in 1915, Saturday Night proclaimed that she was “one of the most profoundly original and technically accomplished of Canadian artists.” Educated at the Art Association of Montreal and the Slade School of Fine Art in London in the traditional academic curriculum, McNicoll quickly moved on to paint en plein air in a bright and airy Impressionist style. Impressionism was controversial in Canada long after its emergence in France, and McNicoll became a key player in popularizing it in this country.

Early Education

Helen McNicoll’s oeuvre demonstrates an impressive breadth in subject matter and an assured mastery of technique. McNicoll began her formal art education at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM) in 1899. The institution’s school, acknowledged as the best in Canada and directed by William Brymner (1855–1925), was at the centre of a burgeoning Montreal art scene. Brymner had trained in Paris at the well-regarded Académie Julian and transmitted his European education to a new generation of Canadian students.

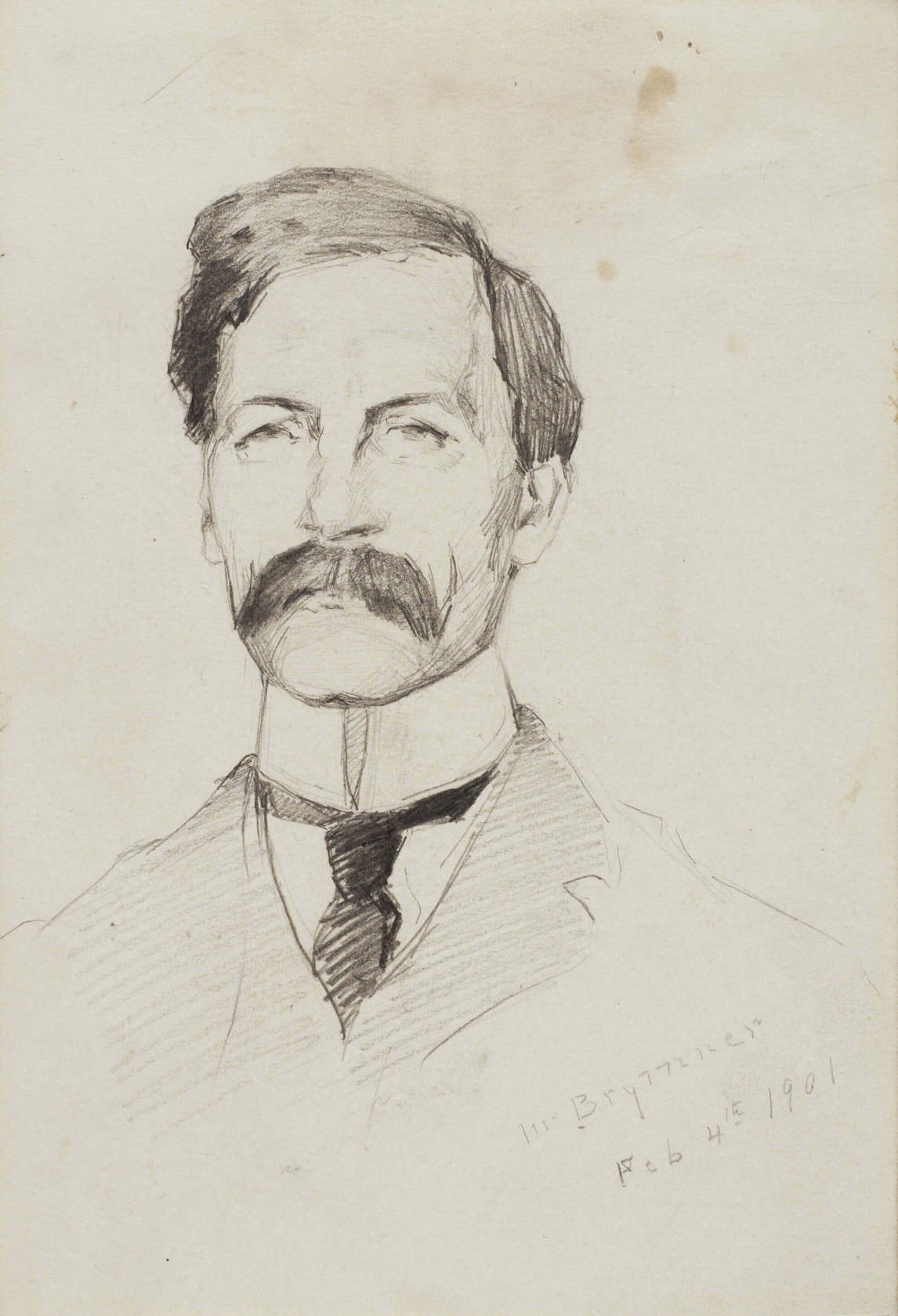

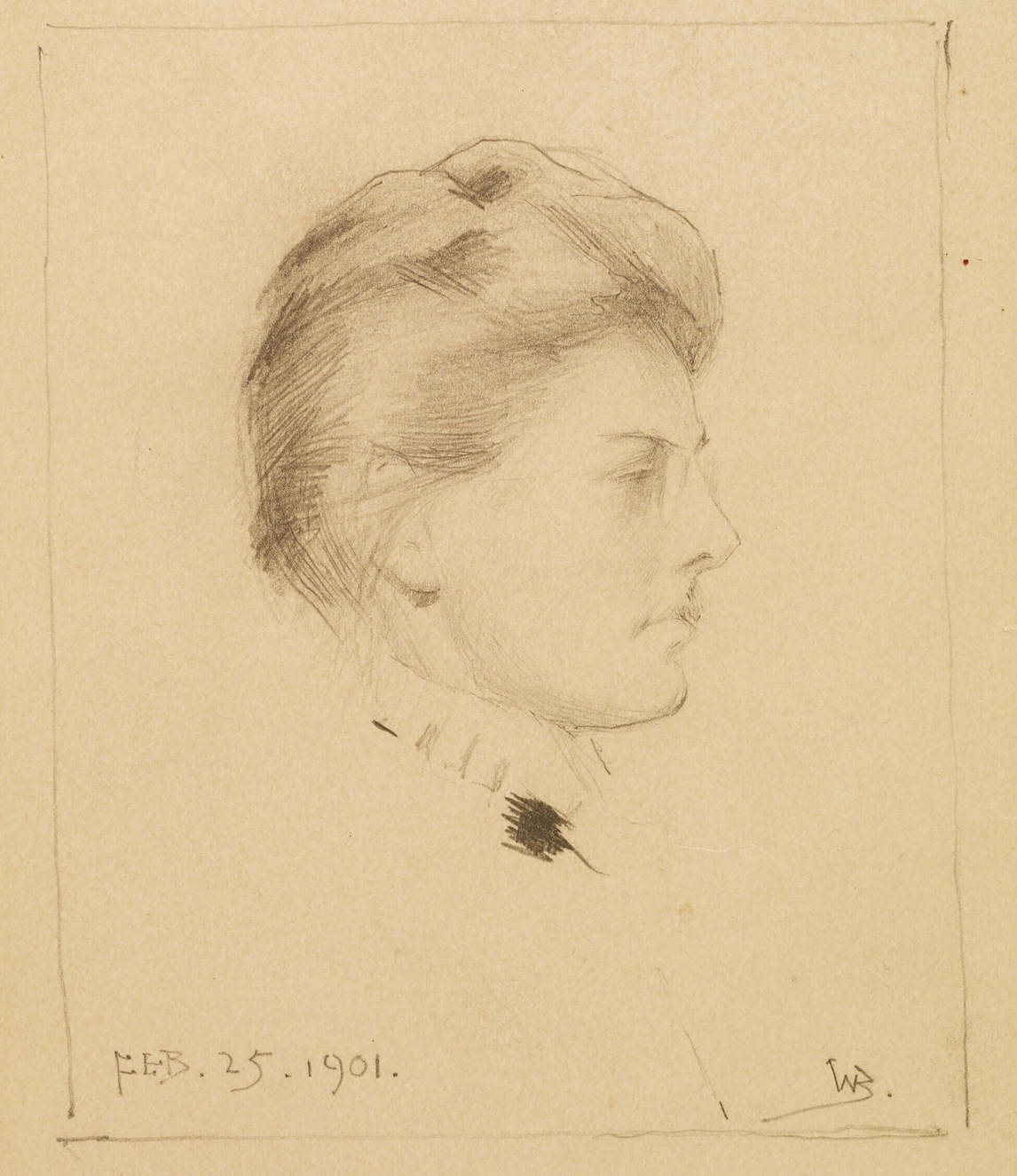

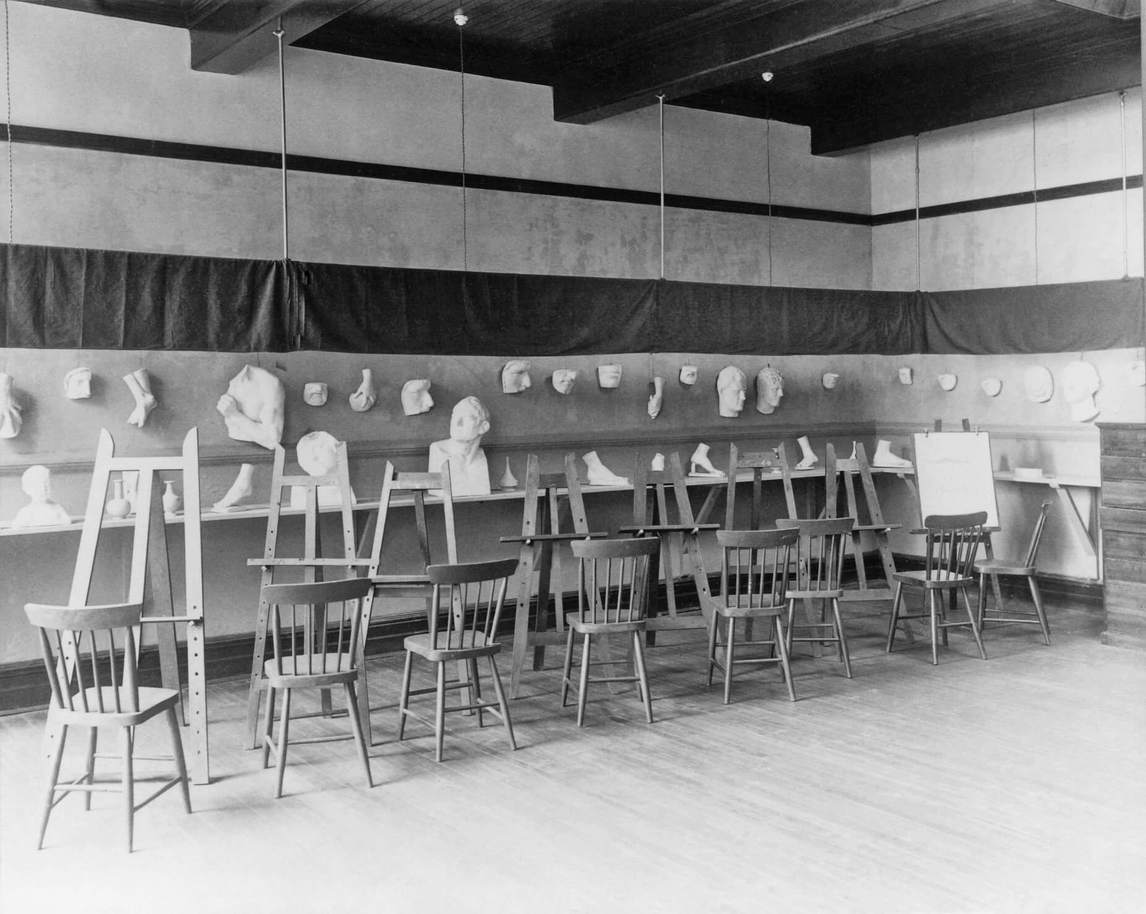

The AAM school followed a traditional academic curriculum modelled on those in prestigious institutions such as the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and the Royal Academy of Arts in London. McNicoll and her fellow students attended classes in painting and illustration as well as lectures in anatomy and art history. They were encouraged to copy paintings in the AAM’s galleries and to draw one another and their professors. McNicoll’s sketchbook from the period includes likenesses of Brymner and his assistant teacher Alberta Cleland (1876–1960).

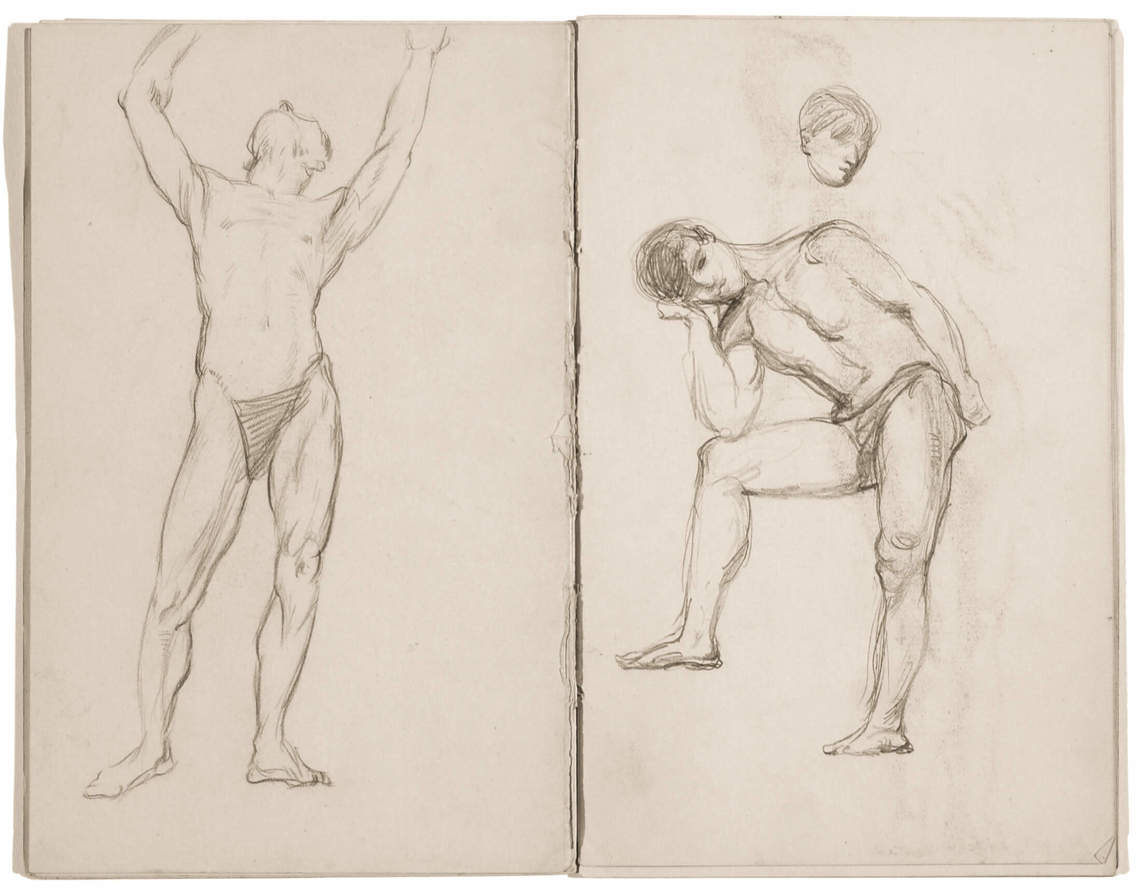

The foundation of the AAM curriculum was drawing. Students began by drawing isolated parts and more complex groupings from plaster casts of antique sculptures and reproductions of Old Master paintings. Only after they gained a level of mastery were they permitted to draw from live nude models. Skill in depicting the anatomy, pose, proportion, and movement of the body was believed to be the necessary foundation of painting. McNicoll had ample practice in nude studies both at the AAM and at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Drawings in her sketchbook from the period show careful attention to the musculature, motion, and balance of the human body.

Plein Air Naturalism

As a student at the AAM, McNicoll had the opportunity to attend outdoor sketching classes, where Brymner’s European experience was again evident. In France he became familiar with painting en plein air, which, by the 1870s, was popular because of the expanding Naturalist movement. Plein air Naturalism featured rural genre scenes and landscapes, frequently combining an academic approach to the figure with a modern treatment of light and colour. The peasant subjects of Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848–1884) and other artists were enormously influential and extremely popular with contemporary audiences. In Canada, the Naturalist trend was most visible in the works of the Dutch Hague School, which were prominently featured on the walls of the AAM galleries and in the homes of private collectors, including the McNicoll family. The influence of this school is strong in McNicoll’s early works, such as River Landscape, n.d., and Cottage, Evening, c. 1905.

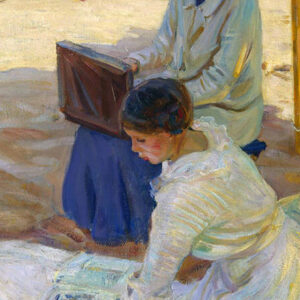

When he took his students into the countryside to paint directly from nature, Brymner advised them to use the inhabited landscape as their subject, carefully observe the effects of light and air, and strive for an unaffected, natural approach in their brushwork and surface “finish.” McNicoll continued to work en plein air for the rest of her career, producing sketches outdoors which she then finished in a studio. She would have benefitted in this practice from the relatively recent invention of portable oil paint tubes; we see a typical paintbox in Under the Shadow of the Tent, 1914. While she apparently had a camera, she does not seem to have used it as an artistic tool, preferring to sketch directly from nature. These plein air lessons continued to influence McNicoll’s work long after she left Montreal; one critic praised paintings such as A Welcome Breeze, c. 1909, as possessing “a quality of open-air sunshine, disarming all thoughts of labour in the studio, and … reaching the distinctive height of art concealing art.”

McNicoll left Montreal in 1902 to attend the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London. Known as an avant-garde alternative to the old-fashioned Royal Academy of Arts and as a woman-friendly institution, the Slade was home to a number of prominent teachers and students who would shape the modern art scene in England in the first years of the twentieth century. Included among them were teachers such as Henry Tonks (1862–1937), Fred Brown (1851–1941), and Philip Wilson Steer (1860–1942) and students such as Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957), William Orpen (1878–1931), and Augustus and Gwen John (1878–1961 and 1876–1939). The Slade, together with the access it provided to the galleries, museums, and studios in London, gave McNicoll the opportunity to engage with modern artistic practice on a level not yet available in Montreal.

England also offered new possibilities for plein air practice. McNicoll left London for the remote southwest village of St. Ives in 1905, where she attended the Cornish School of Landscape and Sea Painting. Run by Swedish-British artist Julius Olsson (1864–1942), the school was a popular destination for students who wanted to paint seriously in a rural setting. Olsson was himself primarily a marine painter whose favourite subject was the waves crashing on the rocky coast. He was known for pushing plein air practice to its limits. He allowed his students to work in the converted fish loft that served as the school’s studio during thunderstorms, but forced them to paint on the beach in bright sunlight at all other times. Olsson’s assistant Algernon Talmage (1871–1939) was also a strong proponent of the plein air technique, asking students to paint in sunny fields and orchards. McNicoll’s numerous images of seaside and rural landscapes—An English Beach, c. 1910, The Orchard, n.d, and Reaping Time, c. 1909, for example—were clearly influenced by her time working outdoors with Olsson and Talmage in St. Ives.

St. Ives was one among a number of rural villages across Europe that catered to painters looking to escape urban centres. Whether in England, France, or further afield, they could generally expect to find friendly colleagues, quaint subjects, and a ready-made infrastructure for painting in these “artists’ colonies”; the colonies were also relatively inexpensive and appealingly bohemian. It was common for artists to travel from village to village: McNicoll worked in several across England and on the Continent, including Grez-sur-Loing in France. It was largely through this network that plein air Naturalism, and later Impressionism, spread across Europe. While McNicoll’s work is clearly influenced by Brymner, Olsson, and Talmage, she eventually pushed further into a more fully realized Impressionist style than did any of her early teachers.

The Origins of Impressionism

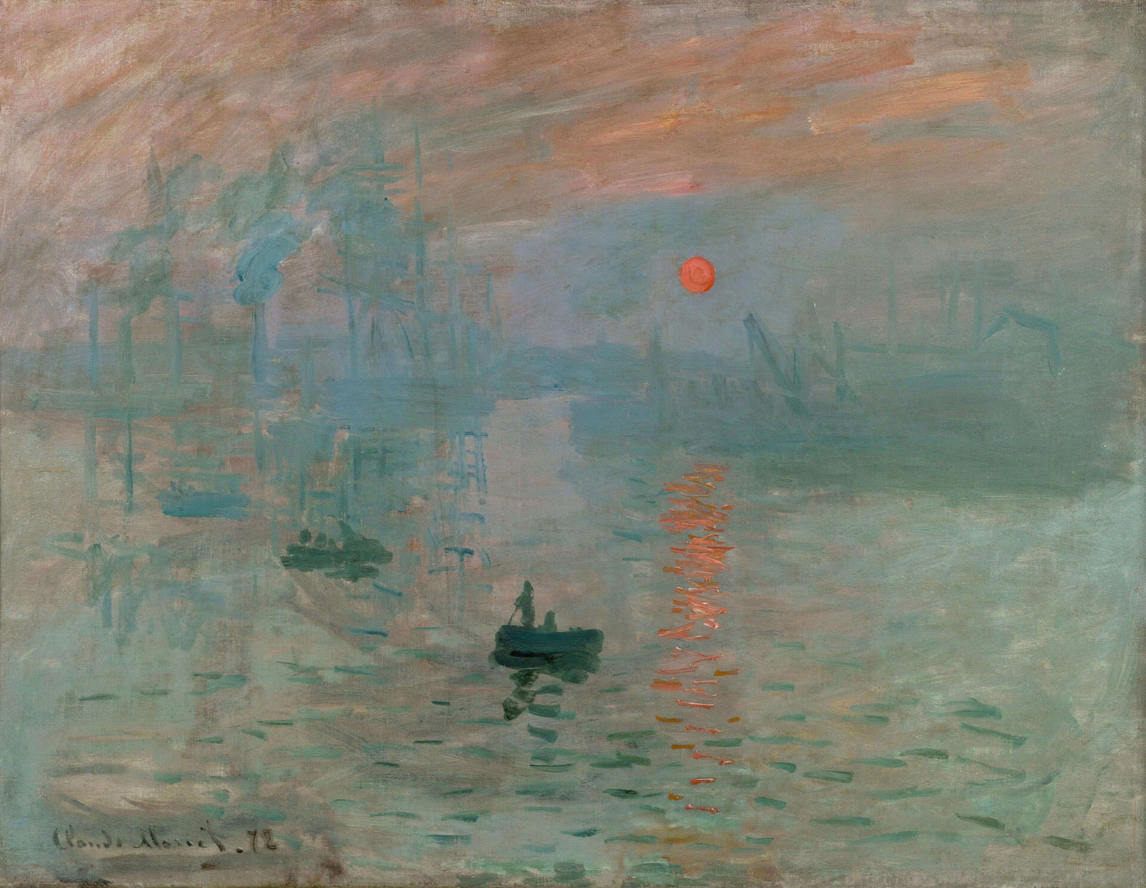

McNicoll was one of only a small number of Canadian artists to fully adopt Impressionism as a style. This movement originated in Paris in the 1860s when a group of young artists who were dissatisfied with the traditional Salon came together to organize their own exhibiting opportunities. Key figures associated with Impressionism in its first years included Claude Monet (1840–1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894), Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), and Berthe Morisot (1841–1895). Monet’s Impression—Sunrise, 1872, gave the movement its name when a critic referred to it disparagingly in his review of the first official group exhibition in 1874.

There were eight exhibitions in total, the last in 1886. Impressionism was not immediately popular. Many of the artists were initially rejected for their innovative approaches: their paintings were small in scale, while monumental pictures dominated the walls of the Salon; their subjects, scenes taken from everyday modern life, were considered unworthy of high art; and their stylistic choices—a flattened sense of perspective, bright daubs of pure colour, divided brushstrokes, and a loose finish—frequently resulted in the amused confusion of critics and popular audiences. These features are well illustrated in the compressed space and sharp cropping of Caillebotte’s On the Pont de l’Europe, 1876—77, for example, and the quick brushwork of Renoir’s The Swing, 1876. Working more than thirty years after Impressionism’s start, McNicoll would adopt all of these strategies in paintings such as Tea Time, c. 1911.

The Impressionist movement emerged at a moment of immense change in France. Paris had been irrevocably transformed—politically, socially, and physically—by the successive upheavals of the Revolution of 1848, the rebuilding of Paris by Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann through the 1850s and 1860s, the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–71, and the Paris Commune of 1871. In subject and style, the movement took inspiration from French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire, who urged artists to seek out modernity in their work, which he defined as “the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable.”

Above all, Impressionist painting is characterized by this sense of transience. Although individually different in many respects, the early Impressionists were united by an effort to capture for posterity the world as seen by a single individual at a single moment in time: to paint what they saw rather than what they knew. This fundamental emphasis on individual perception, and especially on the subjective effects of light and air, was clearly handed down to McNicoll and is apparent in the sketchy brushwork and purple shadows of The Avenue, c. 1912.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Impressionism had spread far outside Paris. Natalie Luckyj suggests that McNicoll may have seen works by the French Impressionists at a large exhibition of some three hundred paintings organized by French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1905. In 1910, McNicoll likely attended another important exhibition: Roger Fry’s Manet and the Post-Impressionists, often credited with introducing modern French painting to England. By the end of the nineteenth century, Impressionism had been diluted and combined with the plein air Naturalism of the rural artists’ colony circuit to become the foremost international style. Unlike many of her peers, however, McNicoll maintained a strong attachment to the fundamental principles of “pure” Impressionism and pushed the style further than any other Canadian artist.

Impressionism in Canada

Impressionism only gained currency in Canada almost three decades after its introduction in Paris. Instead, Hague School and Barbizon landscape works dominated the Canadian art market at the end of the nineteenth century. Gradually, however, a small number of collectors in Montreal showed an interest in modern French painting. In 1909, William Van Horne (1843–1915) purchased McNicoll’s A September Morning (date and location unknown) adding it to canvases he owned by Renoir, Cassatt, and other Impressionists.

Montreal was the primary centre of Impressionism in Canada. In 1892, W. Scott and Sons Gallery sponsored the first exhibition of eight French Impressionist works, and others followed, including a show of Cassatt’s delicate, Japanese-inspired etchings of modern women and children at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM) in 1907. It is tempting to imagine that McNicoll might have seen the show and taken inspiration from it. William Brymner was a leading proponent of Impressionism in its early years in Canada. Although he never fully adopted Impressionism in his own work, he encouraged Montrealers to open their minds to this trend. As he explained in a public lecture in 1897: “Impressionism is the modern manifestation of the eternal fight between the living and the felt … between the work of men who see and think for themselves and those who inherit their eyes and thoughts all ready-made.” Brymner’s lecture, with its emphasis on careful observation and individual perception, provides a glimpse into what McNicoll and her contemporaries learned about modern art at the AAM.

Beginning in the 1890s, a small group of Montreal artists led by Maurice Cullen (1866–1934) and James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924), both of whom had worked with Brymner in France, tried to import Impressionism to Canada. Cullen’s scenes of light reflected on snow, such as The Ice Harvest, c. 1913, come close to a “native” Canadian Impressionism, though there was little cohesiveness among Canadian practitioners. Few painters fully adopted the style as McNicoll did. With some exceptions, scenes of modern urban life were much less popular in Canada than in France and the United States, and landscape and rural genre scenes continued to dominate. McNicoll’s own work, in paintings such as Midsummer, c. 1909, follows this trend.

McNicoll belonged to a second generation of Canadian Impressionists that included Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942) and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937), both fellow Montrealers, and W.H. Clapp (1879–1954), with whom she shared the inaugural Jessie Dow Prize at the 1908 AAM Spring Exhibition. The winning canvases, McNicoll’s September Evening, 1908, and Clapp’s Morning in Spain, 1907, are both clearly inspired by Impressionism. Many of these artists trained with Brymner and went abroad within a few years of each other. Reviews of the AAM Spring Exhibitions through the first decade of the twentieth century refer to these artists’ loyalty to the “New Painting” and the “French Method.” In a characteristic review from 1909, a critic wrote that “Miss McNicoll has for some time past been studying on the continent, and she has certainly caught the spirit of the modern French Impressionist school.”

Though the reception of Impressionism in Canada was frequently ambivalent and sometimes overtly negative, McNicoll’s work was almost unanimously well received. Some critics objected to her representation of water as rigid and unnatural—Fishing, c. 1907, for example, drew this criticism—but reviewers were generally supportive of her efforts, saying that she avoided the “extreme effects and extravagant technique” of some of her peers. Her gender may partially explain this positive reaction: Norma Broude and Tamar Garb have noted that Impressionism was coded as a feminine style and that women Impressionists received positive notice for their soft, pretty treatments of everyday subjects, even as their male colleagues received criticism for those same qualities.

Impressionism had a short life in Canada. When McNicoll was receiving positive notice for her canvases, the movement was already nearly forty years old in France, and the established avant-garde movement was Cubism. By the time Impressionism was widely accepted by the public in Canada, artists such as Emily Carr (1871–1945), Emily Coonan (1885–1971), and the Group of Seven had moved on to Post-Impressionist styles. McNicoll’s own brief career neatly mirrors the short burst of attention given to Impressionism in Canada in its day.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements