Helen McNicoll, one of Canada’s foremost Impressionist artists, achieved considerable success in Canada and England during her short career. Part of the last generation of Canadian artists who commonly trained and worked abroad, she played an important role in linking the art worlds across the Atlantic. She lived at an exciting moment for women artists as they experienced new levels of professional acceptance. Although she is known today for her sunny representations of women and children, her paintings often engage with domesticity and femininity in complex ways.

Connections between Canada and Abroad

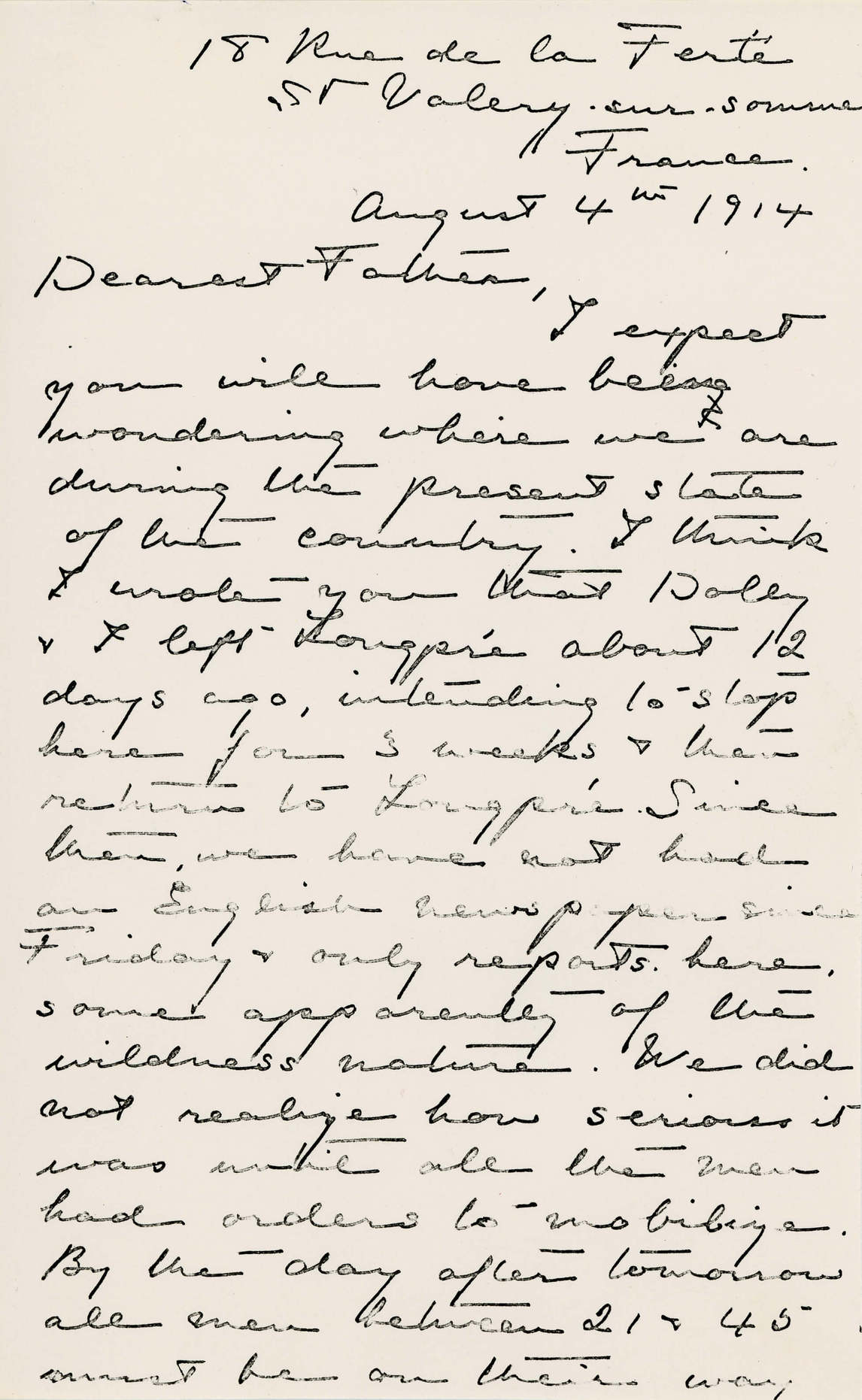

Helen McNicoll deserves to be seen as a key player in the history of Canadian art and as an important participant in a wider network of transnational artistic exchange at the turn of the twentieth century. She was one of a number of Canadian artists who studied abroad in the decades between Confederation and the First World War. If earlier generations of artists had been limited by the distance across the Atlantic, significant innovations in communication and transportation after the 1870s meant that the art worlds of North America and Europe were more tightly linked than ever before. Artists such as Emily Carr (1871–1945) documented their steamship and railway travels in sketchbooks, while McNicoll described her travel in letters home to her family. Going abroad was thought to be a necessary step in the professionalization of young Canadian artists: although Montreal and Toronto were quickly growing in stature, they continued to trail European cities as centres for art education and exhibition.

After training at the best schools in Paris and London, many Canadian artists, such as James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924) and William Blair Bruce (1859–1906), remained abroad to pursue their careers. Although McNicoll never returned to Montreal permanently, she exhibited annually at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM), the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), and other Canadian institutions, and her foreign achievements were reported in the local press. As such, she was one of many expatriate artists who played a role in the transmission of international styles and subject matter to Canada. McNicoll was especially important in helping to extend the reach of Impressionism in Canada at a time when the movement was neither critically nor popularly successful.

McNicoll studied in London rather than Paris, the established capital of the art world, probably because of her family background and the common language that, with her loss of hearing, made it a natural destination for her. The British capital may also have been an attractive option for women artists going abroad to study: Paris had a reputation of bohemian “wickedness” unsuitable for respectable middle- and upper-class women living away from their parents. Other Canadian women who went to England in this period include Frances Jones Bannerman (1855–1940), Sophie Pemberton (1869–1959), and Mary Bell Eastlake (1864–1951). There are few records of artists of colour or French-Canadian artists studying there in this period.

McNicoll and her generation of Canadian artists were, however, the last to consistently study abroad. When war broke out in 1914, European travel for pleasure and study became all but impossible. After the war, a strong nationalist preference emerged for subjects and styles that were uniquely Canadian, as exemplified by the works of the Group of Seven. Impressionist canvases, such as McNicoll’s The Blue Sea (On the Beach at St. Malo), c. 1914, were viewed as too European and old-fashioned in comparison to the modernist Canadian landscapes of artists like Lawren Harris, and fell out of favour. Nevertheless, as today’s art world becomes increasingly globalized, McNicoll and her peers provide an important model for understanding contemporary transnational artistic networks.

Women’s Access to the Art World

Any discussion of McNicoll must acknowledge the role that gender played in the production of her work. She was active at a key moment for professional women artists. In the later nineteenth century, women artists in Europe and North America initiated a dramatic and sustained fight for access to education and exhibition opportunities on the same level as their male peers. Although women students continued to be barred from entry to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris until 1897, a number of competing art schools emerged to cater to serious female students; first among them was the Slade School of Fine Art in London, which McNicoll attended from 1902 to 1904. But even as women artists made gains on the educational front, other doors remained closed to them until long after McNicoll’s death: it wasn’t until 1933, for example, that Marion Long (1882–1970) became the first female artist elected to full membership of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts since Lady Charlotte Schreiber in 1880.

In response to these exclusions, women created their own opportunities. McNicoll was a member of the Society of Women Artists (SWA) in London, and her partner, Dorothea Sharp (1874–1955), served as its vice-president. Originally established in 1856 as the Society of Female Artists, it sought to gain access for women to the male-dominated art world. McNicoll’s letters reveal why she found membership in a women’s-only society appealing. Following her election as an associate member of the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) in 1913, she describes one experience at a “stormy meeting” when British artist and suffrage activist Ethel Wright (1866–1939) complained about the way her paintings had been hung in an exhibition:

She and Dolly [Dorothea Sharp] and I were the only women there … [and she] protested [that] the hangers were “ratters” and the hanging was a disgrace. You never saw so many angry and helpless looking men—when one who tried hard to keep her out of the society, moved that if she did not apologize she should resign. And she did resign, then and there. It was too bad because although her work was rather extreme it was interesting and helped to brighten the show.

As women, McNicoll, Sharp, and Wright were acutely aware of their precarious position in the association. Alternatives like the SWA provided a strong network of patronage and professional support when traditional institutions failed to do so; in Canada, the Women’s Art Association served this need after 1890. At the Art Association of Montreal (AAM), the Women’s Art Society promoted the work of women artists like McNicoll, who won their prize for Under the Shadow of the Tent in 1914.

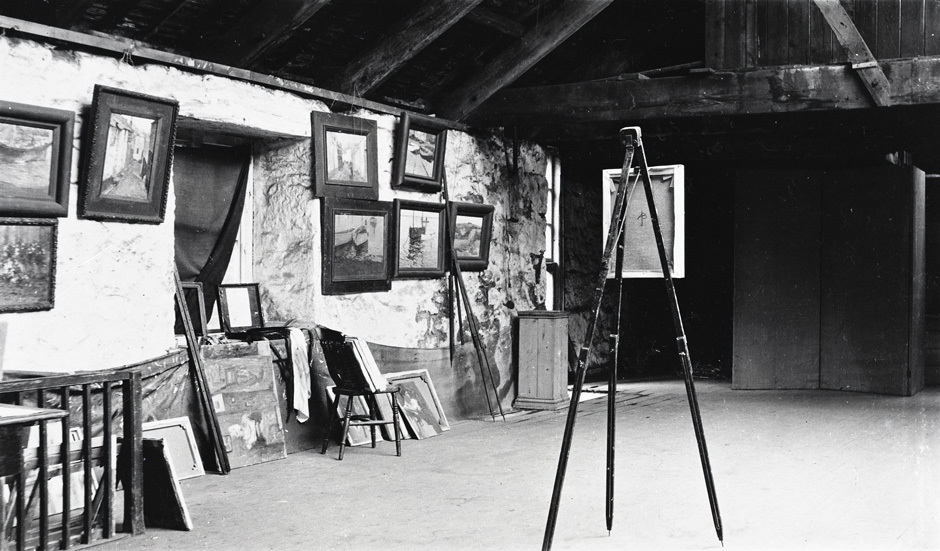

Deborah Cherry and Janice Helland have shown that informal personal relationships also helped to bolster a woman artist’s professional career. McNicoll’s close relationship with Dorothea Sharp was one among many fostered by Canadian women in this period: Florence Carlyle (1864–1923), for example, lived and worked with Judith Hastings (dates unknown), and Harriet Ford (1859–1938) with Edith Hayes (1860–1948). In Canada, the partnership between Frances Loring (1887–1968) and Florence Wyle (1881–1968) became the core of an important circle of artists in Toronto through the 1920s, while the women of the Beaver Hall Group in Montreal formed a tight network that blurred the lines between personal and professional.

For an expatriate like McNicoll, fostering these relationships would have been especially important for success in a new country. Together, women like McNicoll and Sharp could share the costs of studio space, support one another during their travels, and give immediate feedback while they painted. The pair frequently painted similar subjects, as seen in McNicoll’s Watching the Boat and Sharp’s Two Girls by a Lake, both c. 1912. Given McNicoll’s hearing loss, Sharp must also have provided important help in navigating the more practical parts of artmaking: hiring models, renting lodgings, and purchasing supplies. It also appears that Sharp played an important role in encouraging McNicoll to exhibit her work publicly in Montreal and London and to join formal professional associations. Letters show that Sharp advocated strongly for McNicoll before her election to the RBA. “Dolly worked very hard,” McNicoll wrote to her father. “She went around amongst the members and brought them up to my pictures[;] if they didn’t like them, she went after others.” In return, McNicoll opened doors in Canada for Sharp, who exhibited at the AAM on at least one occasion.

Perhaps the greatest challenge for women was in being acknowledged as “professional” artists. Although women—especially women of high social standing like McNicoll—had long been encouraged to draw and paint as a demonstration of their refinement, they had difficulty in rising above the status of amateur in the eyes of art historians and curators. McNicoll does not seem to have suffered from this perception; she exhibited widely and sold her work to public institutions and private collectors. Indeed, her obituary emphasized her professionalism, saying that “Miss McNicoll was no amateur—there are few painters in the Dominion who take their art as seriously as she did.”

However, McNicoll’s reputation after her death seems to have been affected by this issue. When histories of Canadian art began to be written in the 1920s, McNicoll was omitted, as were most of her female colleagues. In a new nationalist narrative, wild, open landscapes were given precedence over quiet domestic scenes such as McNicoll’s Beneath the Trees, c. 1910. Not until the late twentieth century did McNicoll and her peers begin to see some recognition as practising professionals, largely due to the efforts of feminist art historians and curators who have attempted to recuperate their work. Still, research on Canadian women artists in the years before the First World War continues to lag far behind that on their female peers in France, England, and the United States.

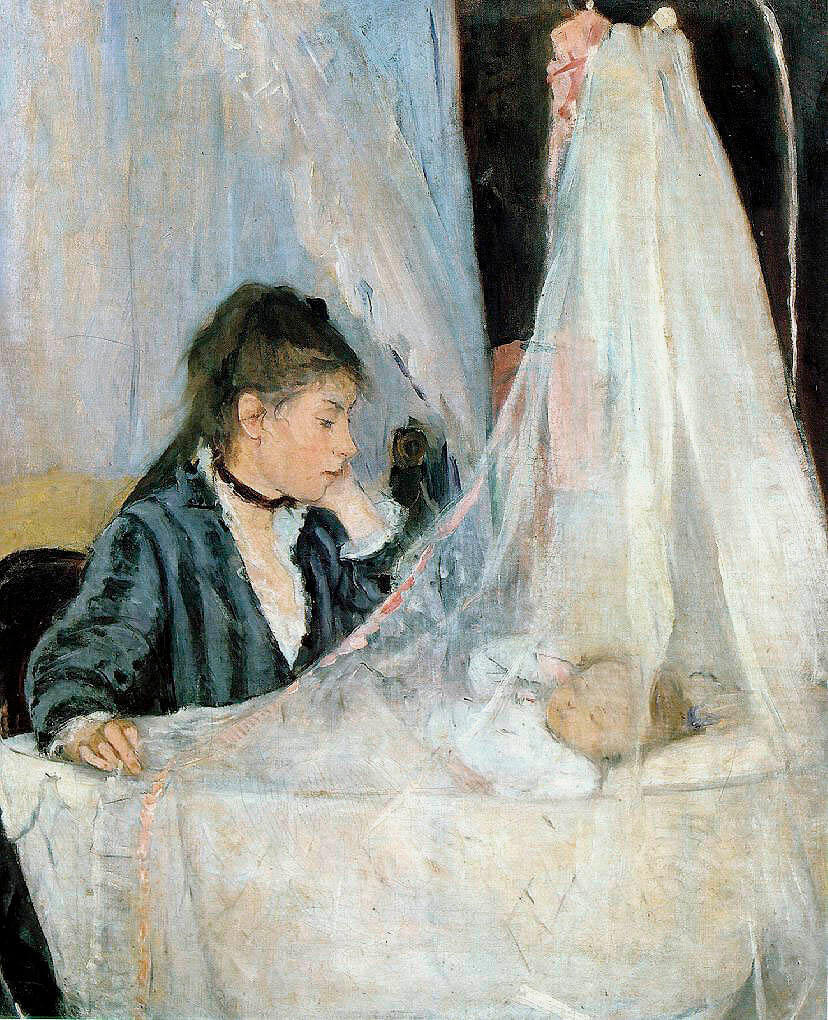

Femininity, Domesticity, and Separate Spheres

Gender is equally important to consider when examining McNicoll’s chosen subject matter. Today, McNicoll is known primarily as a painter of gentle Impressionist scenes of women and children. Critics and art historians compare her to other Impressionist women artists, especially Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) and Mary Cassatt (1844–1926)—the link between McNicoll and Cassatt was made by a reviewer for the Montreal newspaper Le Devoir as early as 1913. For these female artists, the Impressionist interest in the transient qualities of everyday modern life is evident in their efforts to capture scenes from contemporary bourgeois life in the private parlours and gardens of the home rather than in the public spaces of the modern city.

Griselda Pollock and other scholars have argued that women Impressionists did not paint domestic scenes because they were biologically inclined to “feminine” subjects but because they were limited to them by the social standards of the day. In the latter nineteenth century, the theory of “separate spheres” held that middle-class women were affiliated with the private sphere of the home, while men were associated with the sphere of public life. It would have been inappropriate for McNicoll to paint scenes of modern Parisian life similar to those by her fellow Canadian Impressionist James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924). Rather, women artists painted subjects from their lives, often using their friends, mothers, sisters, and children as models.

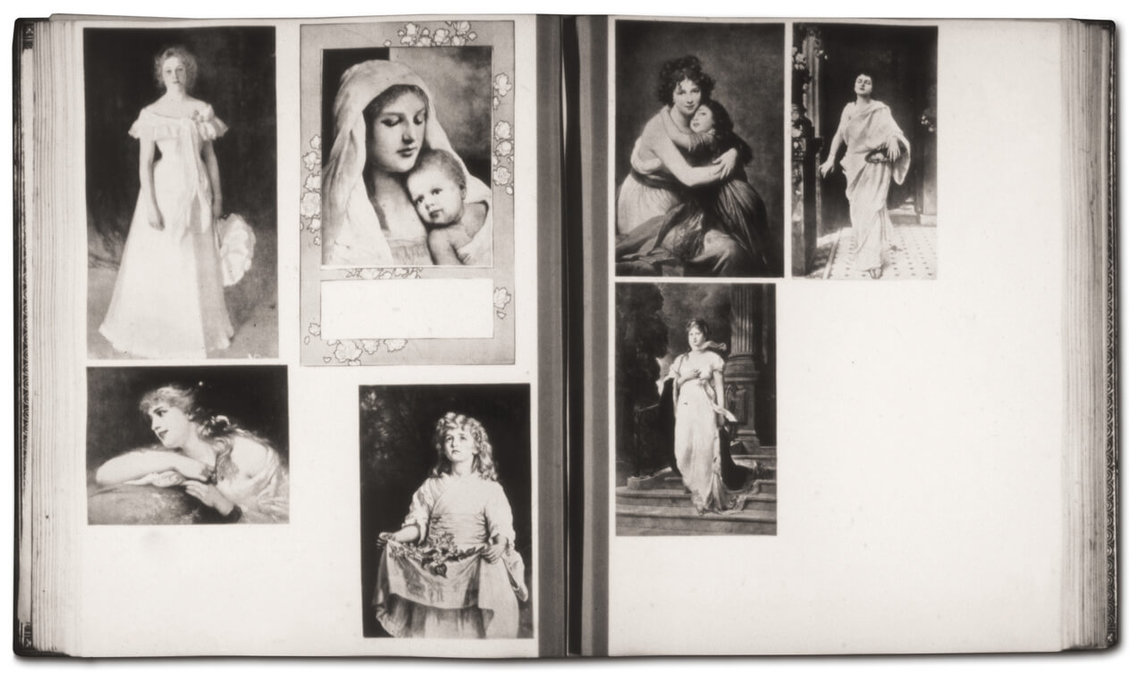

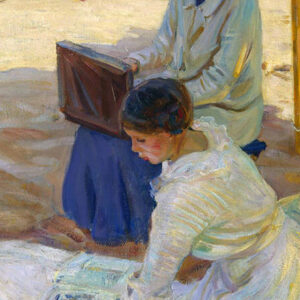

It is clear that these subjects held interest for McNicoll. A scrapbook she kept includes images of women and children alongside reproductions by prominent women artists including Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755–1842) and American illustrator Jessie Willcox Smith (1863–1935). A number of McNicoll’s paintings would take up these same subjects, showing women in domestic settings and performing “feminine” activities such as sewing and reading. McNicoll also played an important role in shaping public understandings of modern childhood through images such as Cherry Time, c. 1912. In this painting, as in her idyllic representations of carefree young girls picking flowers or playing on the beach, she contributes to a body of imagery that Anne Higonnet has argued both reflects and helps to construct the idea of childhood as a special and separate phase of life. It should, however, be acknowledged that these understandings of separate spheres and ideal childhood were specific to white, middle- and upper-class families. McNicoll’s own images of rural working women and children highlight the limits of these discourses.

“A Striking Contrast”

At a closer look, McNicoll’s work seems somewhat uncomfortable with stereotypically “feminine” or “domestic” subjects, and her obituary in Saturday Night notes that she “afforded a striking contrast to the prevailing type of feminine painter.” Kristina Huneault argues that traditional understandings of femininity and the private sphere fall apart in places in McNicoll’s paintings—for example, In the Shadow of the Tree, c. 1914, with the lack of touch between the woman and the child; in Interior, c. 1910, with the absence of the presumed woman in the domestic space; and in both versions of The Victorian Dress, c. 1914, with the unfashionable gown. “There is something faint but perceptible about these initial examples,” she writes, “that lends credence to the idea that femininity does not reside straightforwardly in the world that McNicoll envisions.”

Huneault suggests that McNicoll’s early hearing loss might account in part for the feeling of silence and detachment that is evident in many of her works. Figures do not engage with one another, nor do they connect with the viewer by returning our gaze. Women and children seem locked in their own interior worlds. Alternatively, we might read McNicoll’s subtle discomfort with traditional representations of femininity through the lens of queer studies. Although there is no firm evidence of the exact nature of McNicoll’s relationship with Dorothea Sharp, it seems clear, at the very least, that she chose to pursue a life that did not include heterosexual marriage and children of her own, opting instead for the lifelong companionship of another woman.

Perhaps the most overt example of this discomfort with the traditional discourse of white, bourgeois femininity is McNicoll’s The Open Door, c. 1913. Painted in the same year as her election to the prestigious Royal Society of British Artists, the image depicts a solitary woman, clad entirely in white, sewing a white cloth against the backdrop of an open door. The use of the same shades of white, grey, silver, and beige on the dress, cloth, wall, table, mirror, and floor make it difficult to tell where one object ends and the next one begins, creating the impression that everything in the room—including the woman—fits naturally into the space. But The Open Door also contains signs that indicate the artist’s unease with this natural domesticity, most clearly through the door leading to the outside world, the strangeness of the mirror that doesn’t reflect anything, the uncertainty of what the woman is sewing, and the peculiarity of the woman’s standing position. The title of the work further suggests a world of opportunity: the woman’s coat and hat hang on the door, ready to be worn. All told, the painting serves as a metaphor for women’s increased access to the art world and the gap between the life expected of a white woman of McNicoll’s class and the life she actually lived.

A Legacy Forgotten

The critical acclaim McNicoll experienced during her lifetime did not extend through much of the twentieth century. Perhaps some of the critical and popular neglect of McNicoll and her European-trained peers was because, as expatriates, they were seen as insufficiently Canadian to warrant notice in histories of the nation’s art. Amid the dominance of the Group of Seven and the celebration of a Canadian school of painting, McNicoll faded from public view. In 1926 the inaugural exhibition of the Art Gallery of Toronto (now Art Gallery of Ontario), though featuring only three women artists, included three of McNicoll’s canvases: Reading, Sewing, and Children Playing in the Forest, dates and locations unknown. She received scant critical or public attention in the following years, however, and her work has been mostly excluded from surveys of the history of Canadian art and has remained largely absent from public collections. On the occasion of McNicoll’s memorial show at the Art Association of Montreal in 1925, one writer concluded that works on view “show her rather as an English painter.”

The first hints of a revival appeared in the mid-1970s, when the celebration of International Women’s Year in 1975 led to the recuperation of female artists in Canada and around the world. That same year, McNicoll’s work was included in a major show, From Women’s Eyes: Women Painters in Canada, curated by Natalie Luckyj and Dorothy Farr at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario. Also in the mid-1970s, at the Morris Gallery in Toronto, a large number of McNicoll’s works, most of which had remained in family and private collections, were exhibited for the first time since the artist’s 1925 memorial exhibition. McNicoll also received some notice from scholars interested in Impressionism in Canada, and her work appeared in a number of catalogues and shows through the 1980s and 1990s.

In 1999, Helen McNicoll: A Canadian Impressionist, a major exhibition curated by Luckyj at the Art Gallery of Ontario, restored McNicoll to public attention. Luckyj’s exhibition catalogue introduced the artist to a wider audience and set the stage for further study of her work. In the years since, her paintings have been purchased and exhibited by major institutions and have reached new prices at auction. McNicoll now takes her place as one of Canada’s foremost artists.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements