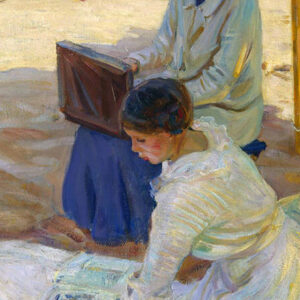

Sunny September 1913

Helen McNicoll, Sunny September, 1913

Oil on canvas, 92 x 107.5 cm

Collection Pierre Lassonde

Sunny September is a pleasant scene of a woman and children who appear to be sightseeing. Their clean white dresses suggest they are not local but middle-class tourists enjoying the view. In the Edwardian period, tourism was a relatively recent form of leisure, and daytripping scenes were popular subjects for French and American Impressionists. McNicoll’s beach scenes join those of artists such as Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Childe Hassam (1859–1935) in portraying a modern theme—one she repeats in On the Cliffs, 1913, and other beach and seaside views. Somewhat unusually, McNicoll’s subject in Sunny September isn’t the undisturbed natural vista traditionally sought by sightseers but the tourists themselves in the act of looking.

Sunny September is also significant because it reveals McNicoll’s skill in representing sunlight—the quality reviewers of her work have praised most consistently. Her obituary in the Montreal Gazette notes her “skill in depicting sunlight and shadow,” concluding that “strong sunlight especially appealed to her.” Recent critics have also celebrated her depictions of “ brilliant sunlight,” her “happy colour harmonies,” and “her concern with rendering the effects of bright sunlight.” In this image of three figures standing on a grassy hill looking out over the beach, the artist represents the effects of sunshine on a variety of surfaces: the shadows accenting bright white dresses, the sunburnt cheeks of the main figure, the alternately green-dappled and yellow-bleached grasses, and the hazy meeting of blue sky and sea.

As in many of McNicoll’s paintings, the senses are evoked in Sunny September: the viewer imagines the warmth of the sun, the smell of the ocean, and the rustling sound of the long grasses. In the words of Canadian critic Hector Charlesworth: “You can snuff the pleasant breeze in this work.” Yet as so often with McNicoll, there is a sense of detachment too: the figures don’t engage with each other, nor do they connect with the viewer. Kristina Huneault has suggested that this frequent feature of McNicoll’s work was a result, perhaps, of her loss of hearing as a child.

This canvas was exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists when McNicoll was elected to that prestigious institution and received positive notice in the Toronto, Montreal, and London press. The Studio included a reproduction in an article that cited McNicoll’s work alongside that of A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Laura Muntz Lyall (1860–1930), and fellow Canadian Impressionists Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937) and Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942). The writer hails them as exciting evidence of a “distinctively Canadian art.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements