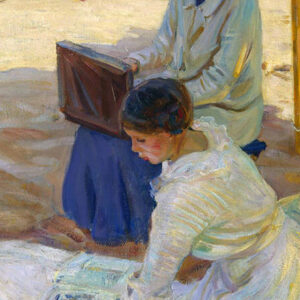

In the Shadow of the Tree c. 1914

Helen McNicoll, In the Shadow of the Tree, c. 1914

Oil on canvas, 100.3 x 81.7 cm

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

McNicoll is best known today as a painter of women and children. She is frequently compared to Impressionists such as Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) and Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), famous for their own representations of motherhood. As a young woman, McNicoll kept a scrapbook with many images of maternity. But although she painted several combinations of young women and children, such as Minding Baby, c. 1911, where an older girl supervises her younger siblings, few of her works can be described as representations of motherhood. In the Shadow of the Tree is one possible exception, though this detached maternal relationship does not resemble Cassatt’s more physically intimate images, as in Mother About to Wash Her Sleepy Child, 1880. Rather than focusing her exclusive attention on the child, the mother (or sister or nanny?) reads a book, lost in her own world as the baby sleeps. Her hand rests on the side of the carriage, not quite touching the child.

This moment of repose is a good example of the tranquil figure studies of modern women taken up by McNicoll in the later years of her career, including Beneath the Trees, c. 1910, The Chintz Sofa, c. 1913, and The Victorian Dress, 1914. These works, frequently featuring women reading and sewing, belong to a long artistic tradition that record women inhabiting their own inner worlds while quietly performing domestic tasks or leisure activities. They are reminiscent, for example, of the Dutch Golden Age work of Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), in which moral virtue is conferred on women pictured alone in domestic spaces.

Scholars such as Rozsika Parker have argued that reading and sewing in the nineteenth century were potentially subversive acts for women confined to the private sphere: they could be viewed as exercises of imagination and fantasy, an escape from the drudgery of housework and child-rearing. In Minding Baby, c. 1911, the older girls, focused on their sewing, have not noticed that the child in the carriage is awake.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements