One of the most notable female artists in Canada, Helen McNicoll (1879–1915) achieved considerable international success during her decade-long career. Deaf from the age of two, McNicoll was esteemed for her sunny Impressionist representations of rural landscapes, intimate child subjects, and modern female figures. She played an important role in popularizing Impressionism in Canada at a time when it was still relatively unknown. Before her early death, she was elected to the Royal Society of British Artists in 1913 and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1914.

Early Privileges and Challenges

Helen Galloway McNicoll skilfully turned her wealth and privilege to her advantage and established herself as a professional artist at a time when this choice was unusual for women. She was born on December 14, 1879, the first child of David McNicoll and Emily Pashley. Her parents, immigrants from Britain, lived briefly in Toronto, where Helen was born, but soon moved to Montreal. There Helen was joined by six siblings—three sisters (Ada, Dollie, and May) and then three brothers (Alex, Ron, and Charles). Although documentation of her life is scarce, her few available letters and sketches suggest that the McNicoll family was close.

The McNicolls belonged to Montreal’s Anglophone Protestant elite. Having worked in the railway industry in Scotland and England, David McNicoll joined the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in the booming 1880s, rising to be vice-president and director by 1906. His work brought his artist daughter into close contact with a circle of prominent families of mainly Scottish descent who lived in grand mansions in the Golden Square Mile at the foot of Mount Royal. This group of industrialists controlled most of Canada’s still-young business world: their social and professional network formed the financial foundation of the city in the decades around the turn of the century.

The McNicoll family lived in Westmount in a large house they christened Braeleigh. The home was designed by Edward and William S. Maxwell, known for their work on two prominent Quebec buildings: the Château Frontenac in Quebec City and the Art Association of Montreal building on Sherbrooke Street (now the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts).

The family’s position in the community helped McNicoll’s career in a number of ways, not least by allowing her to paint freely without worrying about supporting herself by making sales or teaching students. Moreover, her family provided connections to the most prominent art collectors in Montreal at the time—in particular, to William Van Horne (1843–1915), then president of the CPR. The Square Mile set controlled the nascent commercial art world in anglophone Montreal as tightly as it did the business world; francophone art, in contrast, was largely tied to church patronage.

Despite these advantages, McNicoll faced challenges. At the age of two she caught scarlet fever and experienced severe hearing loss. Although she was not listed as deaf in the 1901 census, she lip read and relied on friends and family to help her navigate the social side of the art world, such as networking at exhibitions. She did not attend school but was privately tutored at home.

Sketches she made of students at the Mackay Institution for Protestant Deaf-Mutes (known as the “Oral School”) dating from 1899 suggest that McNicoll must have participated in the school’s programs or classes in some capacity, though she is not listed in official school records. Kristina Huneault argues that McNicoll’s experience at the school would have exposed her to current debates around deaf culture in North America. Attitudes toward the deaf and understanding of how best to manage disability were changing drastically: lip reading, for example, was newly promoted over sign language as a more effective form of communication and a means of integrating people with hearing loss into mainstream society.

Although never mentioned in contemporary reviews of her work, McNicoll’s deafness must have influenced her artistic career on many levels, from her decision to study in London rather than Paris, given the language barrier, to the “quiet” and “detached” approach in her art. Huneault and Natalie Luckyj note the sense of distance between the artist and her subjects and also among the subjects in McNicoll’s paintings. In works such as On the Cliffs, 1913, the figures, absorbed in their inner worlds, do not acknowledge one another, nor do they reciprocate the viewer’s gaze.

Montreal Beginnings

Helen McNicoll began her artistic career in Montreal. In the decades before the First World War, art was flourishing in the city, encouraged by better transportation and communication that allowed artists to train and exhibit abroad and become familiar with European trends. The Art Association of Montreal (AAM), founded in 1860, organized its first annual exhibition in 1880 and began offering classes to local artists. By the turn of the century, the market for Canadian art was dominated by a few commercial galleries and by the AAM spring and fall exhibitions.

Presumably McNicoll’s first drawing lessons were at home: her father sketched during his railway travels, while her mother painted china and wrote poetry. McNicoll began her formal art education at the AAM school, where she was awarded a scholarship for her drawings of plaster casts in 1899. The AAM was at the forefront of arts education in Canada at the turn of the twentieth century. Students followed the academic curriculum long established by prestigious European schools. They learned to draw from reproductions of Old Master paintings and plaster-cast copies of antique sculptures before they moved on to work with nude models. McNicoll’s charcoal and pencil Academy, 1899–1900, demonstrates the kind of instruction she received in these early years, emphasizing careful attention to the modelling of musculature and a subtle approach to light and shade. The AAM adopted a progressive approach to art education by giving female students equal opportunity to draw directly from the nude.

McNicoll studied with William Brymner (1855–1925) during her time at the AAM. As one of the first Canadian artists to study in Paris, between 1878 and 1880, Brymner provided an important model for ambitious young artists. He returned to Canada full of enthusiasm for the latest trends in French art—including plein air Naturalism and Impressionism. As the director of the AAM school for more than three decades, Brymner wielded enormous influence over at least two generations of Canadian artists. He encouraged women students to pursue professional careers, and his impact on McNicoll, as well as many artists associated with the later Beaver Hall Group, was critical.

Brymner encouraged his students to travel to Europe for further education. McNicoll followed that advice, and by 1906 she had moved well beyond her teacher’s relatively traditional approach. She painted rural landscape and genre subjects, but developed a fresh, bright style based on the principles of classic French Impressionism that was ultimately completely her own. Brymner’s A Wreath of Flowers, 1884, for example, is a far more restrained image of children in a field of wildflowers than McNicoll’s surprisingly modern Buttercups, c. 1910.

A European Education

Although the Art Association of Montreal was the best in Canada, European art schools still held more prestige, and most young aspiring professional Canadian artists went to Paris or London for further study and experience. McNicoll followed suit, moving to London in 1902. She enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art, a progressive institution renowned for its equal treatment of women students. The turn of the twentieth century was an exciting time for women artists, as opportunities for exhibition and education expanded considerably following a protracted battle by female artists for equal access to the art world. As early as 1883, artist Charlotte J. Weeks had celebrated the Slade for welcoming men and women students “on precisely the same terms, and giving to both sexes fair and equal opportunities.” As such, the school was a popular destination for Canadian women: McNicoll’s contemporaries Sophie Pemberton (1869–1959), Sydney Strickland Tully (1860–1911), and Dorothy Stevens (1888–1966) all studied there.

London was a thriving art centre, and McNicoll would have encountered work there that was far more progressive than anything in Canada. Her teachers at the Slade were among the most vocal supporters of modernism in England. With their background in the avant-garde New English Art Club, Henry Tonks (1862–1937), Fred Brown (1851–1941), and Philip Wilson Steer (1860–1942) favoured subjects from modern life and careful attention to atmosphere and light. McNicoll’s Slade training can perhaps be glimpsed in her haunting portrait The Brown Hat, c. 1906, where a young woman, dressed in dark tones, stares boldly at the viewer in a way that is reminiscent of portraits by the well-regarded British artist Gwen John (1876–1939), a near-contemporary Slade student.

McNicoll left the school with first-class honours after two years and moved on to St. Ives, in the remote southwest region of Cornwall, to attend the Cornish School of Landscape and Sea Painting. When she arrived in 1905, rural and seaside artists’ colonies were popular. Thousands of artists fled urban centres, particularly during the summer, to paint en plein air in villages across Europe and North America. After the railway connected St. Ives to the rest of Britain in 1877, the town exploded in popularity among artist-tourists coming from countries around the world. Along with myriad quaint subjects to paint, there was the St. Ives Arts Club, a site for socializing and arts criticism that McNicoll attended on at least one occasion. For women artists, rural artists’ colonies offered a lifestyle that balanced ladylike respectability and rebellious bohemianism. Outside the strict social norms of London or Montreal, women artists seem to have found more opportunity to participate in the informal networks of the modern art world.

Although the town newspaper remarked disparagingly that the easels of amateur female painters in St. Ives were “like shells” covering the beach, McNicoll went to the town to work seriously. Her school, founded by Swedish-British artist Julius Olsson (1864–1942) in 1896, was advertised as catering to a clientele of “students adopting painting as a profession.” The studios were located in a converted fish loft overlooking Porthmeor Beach. Photographs of McNicoll at work in St. Ives show her equally rough private studio. McNicoll’s fellow alumna Emily Carr (1871–1945) described Olsson as a harsh teacher and critic: he required students to work outdoors in nearly all weather, demanded they carry heavy equipment, and regularly reduced them to tears with his critiques.

Carr preferred Olsson’s assistant, the British painter Algernon Talmage (1871–1939). McNicoll also formed a close relationship with Talmage; her letters reveal that she admired his work and teaching style and that, for her birthday, he gave her a painting of “yellow sunlight” for much less than its asking price—a gift that caused a stir among her colleagues. Carr recalled that Talmage had encouraged her to find “the sunshine too in the shadows,” a piece of advice that remained with her for the rest of her long career. He must have encouraged McNicoll to look for light and sunshine too. After her time in St. Ives, her work took a sharp turn toward light-filled, airy canvases. Throughout her career, reviewers consistently praised the sunny quality of her paintings.

While in St. Ives, McNicoll met British painter Dorothea Sharp (1874–1955), with whom she would remain close until the end of her life. Sharp was already an established artist: she had studied in London and Paris and exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts and the Paris Salon, and was a member of the Society of Women Artists. McNicoll and Sharp—“Nellie” and “Dolly” to each other—continued to travel, live, and work together until McNicoll’s early death in 1915.

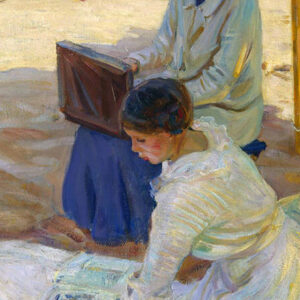

Close relationships between professional women were common in this period, allowing unmarried women to pursue an independent public life with some measure of respectability. For McNicoll, who must have encountered extra obstacles in public due to her hearing loss, a companion would have been especially important. She was grateful for Sharp’s skill in negotiating with models—particularly children, as she enticed them to pose. As they painted together, these two artists frequently produced comparable subjects in similar styles (as in McNicoll’s Girl with Parasol, c. 1913, and Sharp’s Cornfield in Summertime, n.d.), and they also modelled for each other (for example, Sharp in McNicoll’s The Chintz Sofa, c. 1913). Reviewers commented on this likeness at times, occasionally finding in favour of one painter or the other.

London and Beyond

McNicoll led a cosmopolitan life, and in so doing played an important role in the spread of Impressionism from Europe to Canada. She maintained a studio in London from 1908 until her death, using the city as her home base while she travelled throughout England and the continent, usually accompanied by Dorothea Sharp and often by a sister or cousin as well. She made trips to a number of rural artists’ colonies in France and England. In one 1913 letter to her father from Runswick Bay, in Yorkshire, McNicoll writes of the unexpected amenities offered by this itinerant lifestyle, noting that their rented rooms at the baker’s home meant they were eating “delicious bread and cake.” She also mentions that this remote village was something of an artistic hub for Canadians abroad; the family she stayed with was acquainted with her old teacher William Brymner.

McNicoll spent considerable time in France. Although there is some evidence that she worked in Paris briefly—Canadian exhibition reviews from 1909 note that she sent her entries for the annual exhibition season from there—details of this period of her life remain scarce. She opened a studio in Grez-sur-Loing, an artists’ colony south of Paris where British, American, and Scandinavian artists congregated. She also worked frequently in Normandy and Brittany, where she painted warm-toned market scenes such as Market Cart in Brittany, c. 1910, and Marketplace, 1910. Other pictures, including the artist’s brilliantly coloured Footbridge in Venice, c. 1910, reference trips to Belgium, the Mediterranean, and Italy.

This extensive travel must have put McNicoll in direct contact with the innovative artistic styles that percolated in these communities—particularly Impressionism. Thirty years past its explosion onto the Paris art scene, the movement had lost much of its revolutionary charge. Its continued popularity throughout Europe was largely due to the influence of artists circulating throughout rural artists’ colonies, spreading the movement far and wide. McNicoll was one of the first Canadian painters to achieve success working in this style, seen in her early effort Landscape with Cows, c. 1907. By continuing to send her overseas work to exhibitions in Canada, she played an important role in further extending the movement’s reach in this country.

Professional Success

Although she would never return to Canada permanently and lived abroad for the remainder of her life, McNicoll made annual trips to Montreal and kept a studio there for several years. It was in Canada that she first saw professional success. In 1906, she made her debut with six paintings at the annual exhibition of the Art Association of Montreal (AAM); in the same year, she also exhibited with the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA) and the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA).

Charles Gill, a critic for the Montreal paper Le Canada, mentioned her contributions to the AAM show: “Mlle H.G. McNicoll a du talent; ses six envois en attestent.” He selected In the Sun, date and location unknown, as particularly worthy of note—the first reviewer to bring special attention to McNicoll’s sunny canvases. The following year other critics praised her fresh technique and treatment of light. One writer for the Montreal Standard singled out The Little Worker, c. 1907, at the RCA exhibition, stating that “Miss McNicoll has made great strides since last year, and is now being spoken of as an artist who will undoubtedly come to the front very soon.”

The reviewer was prescient: in 1908 McNicoll was awarded the AAM’s inaugural Jessie Dow Prize for her canvas September Evening, 1908. The $200 prize, which she shared with fellow Montrealer W.H. Clapp (1879–1954), also a former Brymner student, was given for the “most meritorious oil painting by a Canadian artist.” Exhibited alongside two rural child subjects, The Farmyard, c. 1908, and Fishing, c. 1907, McNicoll’s work received a prominent place in the exhibition and enthusiastic notice in the press. A critic for the Montreal Gazette said that the competition had been fierce, mentioning that “Miss McNicoll’s art has been deepening and broadening during the past few years and her four canvases in this year’s exhibition aroused discussion and recognition from the first.” The artist would continue to receive praise for landscape and rural subjects, such as Moonlight, c. 1905, throughout her career.

By the end of the decade, McNicoll was consistently recognized in Canada as adopting an advanced Impressionist technique; her treatment of light and air and her bold use of colour were frequently praised by critics, and her canvases hung alongside those of other Canadian practitioners of the style, including Clapp, Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942), and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937). She saw further professional success when A September Morning, date and location unknown, was purchased by her father’s friend and colleague William Van Horne from the 1909 AAM Spring Exhibition. In 1914, the RCA elected her as an associate member: the highest level a woman could achieve at the time. In addition, the Women’s Art Society of Montreal selected Under the Shadow of the Tent, 1914, for its annual prize recognizing the best painting by a Canadian woman.

McNicoll’s career also blossomed in the competitive British art world. In London she participated in the activities of the Society of Women Artists, where Dorothea Sharp was vice-president. In 1913, she was elected as an associate member of the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA)—a prominent alternative to the prestigious but conservative Royal Academy of Arts in London. Like so many of the institutions with which McNicoll was involved, it was notable for its progressive treatment of women. From the society’s founding in 1824, women were included as associate members and gained full membership privileges in 1902. Around the time of her RBA election, McNicoll increasingly turned her attention to close studies of modern female figures, as seen in White Sunshade #2, c. 1912, The Victorian Dress, 1914, and The Chintz Sofa, c. 1913.

McNicoll’s three contributions to the spring RBA show in the year she was elected, including Sunny September, 1913, were noted with praise in London. McNicoll told her father that, of the eight new members, only she and one other were “unknowns.” She added that her election had been contested because of the dangerously avant-garde quality of her art: “It was the older members who didn’t like my things, one old man said to Dolly, ‘If that picture is right then the National Gallery is all wrong.’ One nice man said to D., ‘It will be a bitter pill for some now that your friend is elected.’ I must send some of my older ones there I guess.” In Canada, meanwhile, her election was the occasion for national pride: one reviewer for the Montreal Daily Star wrote: “Considering there have been only eight elections this year, it is particularly gratifying to Canadians that Miss McNicoll should be one of the chosen.” The article was accompanied by photographs of the artist and her studio in London. Even as she helped to increase the visibility of Impressionism in Canada through her transnational career, she also helped to elevate the status of Canadian art and artists abroad through her participation in the British art scene.

There is no evidence that McNicoll tried to sell her work through the private commercial galleries and dealers that dominated the Montreal art market in this period. Possibly, as a woman from a wealthy family, she had the freedom to experiment with advanced styles like Impressionism, which remained controversial in Canada. Two of her works would enter public institutions during her lifetime: Stubble Fields, c. 1912, was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada, while The Farmyard, c. 1908, was sold to the Saint John Art Club. However, the catalogue for her 1925 memorial exhibition at the Art Association of Montreal shows that many of her works found homes in the collections of Montreal’s elite Square Mile set.

An Early Death

McNicoll was in France with Dorothea Sharp, working at Saint Valery-sur-Somme, when the First World War broke out. Her letters to her father excitedly describe the mobilization of the troops, the lack of trustworthy news, and the camaraderie of locals and foreigners. Although she wrote that they “would rather be here than anywhere,” the Canadian Pacific Railway would not risk the vice-president’s daughter being trapped on the Continent and arranged through its European manager and the French ambassador in London for McNicoll and Sharp to be sent home. McNicoll chronicled her journey through roadblocks and passport checks and mourned her abandoned luggage, talking about rumours of German invasion—“some apparently of the wildest nature.” By the time she completed the letter in London, she was already planning another painting trip—this time to Wales.

In 1915 McNicoll’s career was suddenly cut short when she developed complications from diabetes and died, in Swanage, England, at the age of thirty-five. By then she had amassed an impressive exhibition record of more than seventy works in both Canada and Britain. Several reviews of the 1915 exhibition season in Canada mentioned her death, mourning the loss of a promising artist. Saturday Night stated that “none who saw her recent works can doubt that had she been spared she would have added materially to her own laurels and the reputation abroad of Canadian art.”

Critical notice of her work continued after her death into the 1920s: in one 1922 review of the Art Association of Montreal’s Spring Exhibition, the writer paired McNicoll with Tom Thomson (1877–1917), whose work had also been included posthumously: “These examples add much to the interest of the exhibition, but … leave one with a pang of regret that these painters should have passed on.” In 1925, the AAM organized a memorial exhibition of 150 of her paintings, celebrating a prolific career cut short in its prime.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements