Harold Town made a distinct contribution to the Abstract Expressionist movement in 1950s Canada as a member of Painters Eleven. He went on to launch numerous and varied bodies of work, usually executed in series, always with an experimental rigour and in pursuit of a consistent and evolving set of themes. His paintings and collages, drawings, and prints create a dynamic dialogue between traditional artistic modes and the contemporary urban, technological environment.

Action Painting

With his early international success and his determination to make world-challenging art while remaining rooted in Toronto, Town contributed a new confidence and maturity to the Canadian art scene from the late 1950s on. During this early period he wholeheartedly espoused the imperative for “action painting” articulated by American critic Harold Rosenberg: “A painting that is an act is inseparable from the biography of the artist…. [It] is a ‘moment’ in the adulterated mixture of his life.” Town remained faithful to this axiom throughout the vicissitudes of his career. It underlay his rejection of both the formalism championed by critic Clement Greenberg and the “dematerialization” of Conceptual art.

Town’s work is unified by a number of interwoven themes: the collision of technology and nature in the urbanized environment; tensions between spontaneity and order, discord and harmony; human identity as performance and the artist as performer; erotic experience and gender roles; and comments on a period in the history of art when a huge range of visual languages and codes were simultaneously accessible. His late work is stylistically eclectic and asserts a self-conscious awareness of his location in a rapidly transforming world of communications and globalization. Determined to continue within the traditional media of drawing and painting, he opened them up to a self-reflexive exploration of their historical dimensions and contemporary relevance in ways that anticipate the concerns of postmodern painters in the 1990s and after.

Town’s exploration of an extraordinary range of contemporary and historical styles throughout his career was a forward-looking strategy. At the time, artists were expected to develop an original signature style or mode of working and then pursue it single-mindedly, while the art scene was splintering into doctrinaire and mutually exclusive camps. For Town art was a challenging assortment of diverse languages that demanded to be studied and understood. From his vantage point in Toronto, contemporary currents in art had no more claim on him than the art of the past and of other cultures. To each he brought a high respect for technique and craft and the faith that it could expand his horizons and inform his engagement with the world in which he lived.

Rating Town

Town’s work raises the fascinating question of how the enduring value of art is established. His career was long and productive, but while his early Abstract Expressionist work has been broadly praised, his later work was rejected by the powerful art institutions that have shaped the accepted narrative of Canadian art history. Is this, as curator David Burnett argues, because they judged him against the prevailing critical theories that Town himself rejected? Perhaps it is time to re-evaluate Town’s significance.

The standard accounts of modern art have been constructed by art historians in Europe and the United States, for whom Canadian art has been either invisible or deemed provincial. To enter the dominant mainstream, artists of Town’s generation felt pressured to work in a major centre like New York or Paris. Is Town’s significance limited to that of a local phenomenon? Should we value his work as reflective of a provincial experience, or as an example of the margin challenging the mainstream?

Town and Theory

Being the polymath he was, Town took a keen interest in ideas about art and avidly followed contemporary criticism and art history. While he always upheld the primacy of artmaking over theory, his published statements, cultural commentary, and reviews reveal an awareness of the premises of his own art and those of artists he admired.

In 1964, reviewing a retrospective of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), Town characterizes the Spanish artist as “the best maker of variations on a given theme in the history of art,” who had “made many ages of history his own.” His comments on Picasso highlight aspects present in Town’s own art practice. He observes: “Picasso has been seen by many critics as a sort of rocket blazing on and on into space in a straight line…. I think he is more like a wheel with a hub and spokes but no outer rim. He goes up the spoke and then slides back to the hub, picks up another familiar theme and goes up another spoke.” The spokes of Town’s wheel were his appropriations of historical and contemporary art modes and his exploration of media that accommodated his combination of technical virtuosity and intellectualism. The central hub that held his many and varied projects together was his enduring commitment to Rosenberg’s vision of art as a continuous exploration and analysis of self and world.

Rosenberg, and with him Town, rejected Greenberg’s prescription that painting and sculpture should act as autonomous disciplines, purge all external demands and realms of reference, and explore only their own inherent properties and constraints. They found this a reductive, academic formula and objected to its implied linear narrative of modern art as a progressive purification of art from all extraneous demands. Rosenberg regarded contemporary art since the Second World War as the product of a fundamental rupture. “All the art movements of this century, and some earlier ones,” he wrote in 1966, “have become equally up-to-date.” With society and values in continuous turmoil, and all of art history and the prewar modern movements now simultaneously accessible and legitimate, artists were faced with what he called the “anxiety of art”—the question of what to do in the face of this superabundant choice, when everything seemed already to have been done.

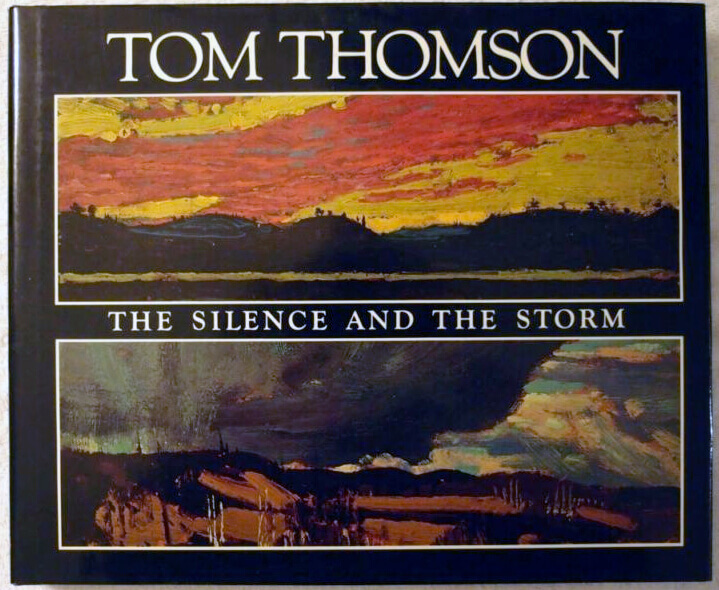

Book cover of Tom Thomson: The Silence and the Storm by Harold Town and David P. Silcox. A prolific author and journalist, Town wrote about institutions, exhibitions and artists as diverse as Thomson, Albert Franck, and Pablo Picasso.

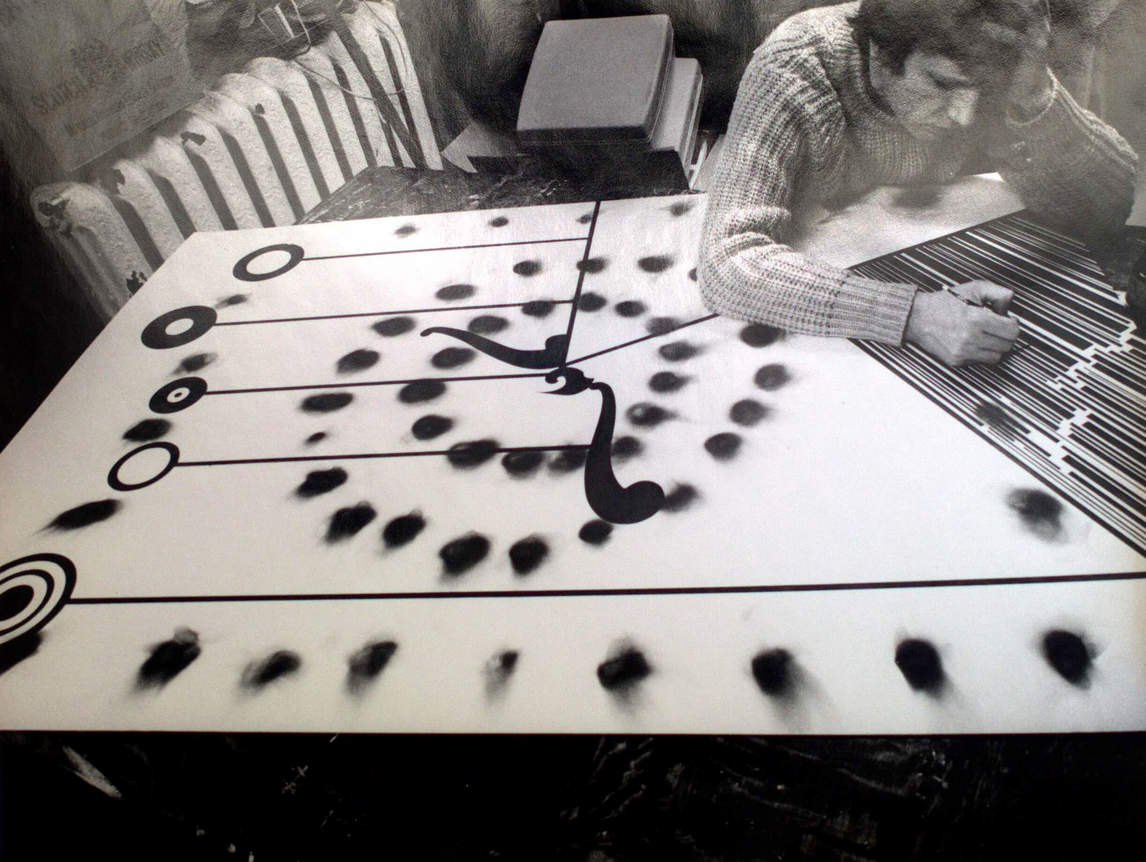

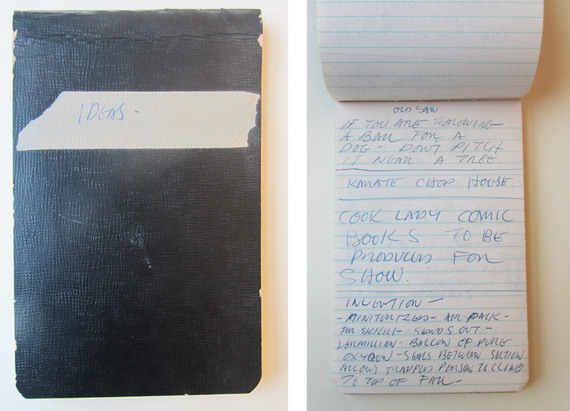

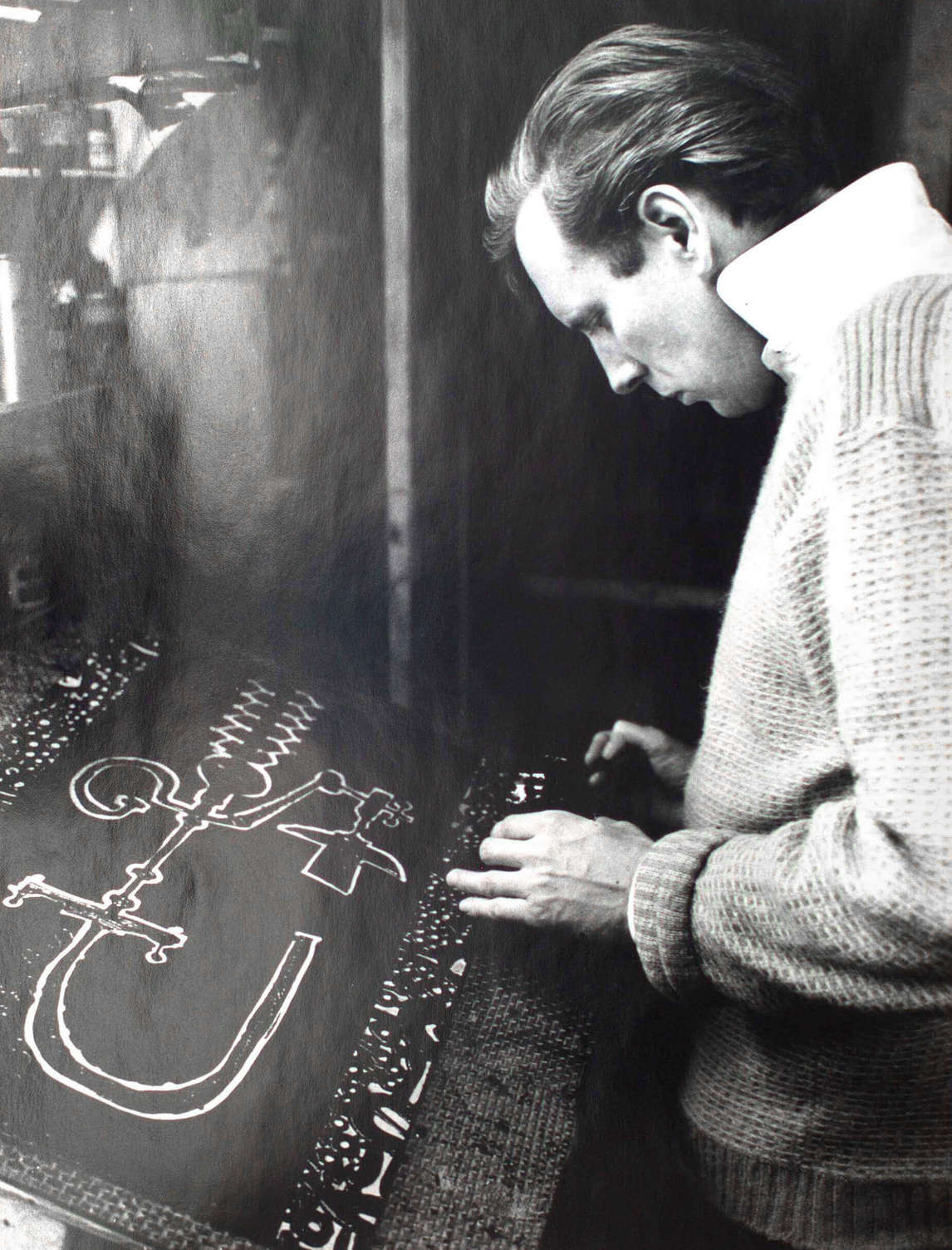

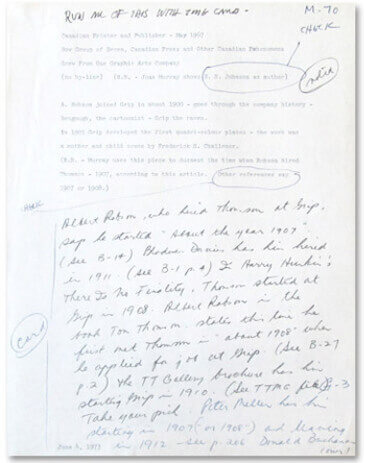

Manuscript page for Tom Thomson: The Silence and the Storm.

For Rosenberg the source of artistic value lies not in art’s material products or stylistic turns, but in the unfolding mind of the individual artist who takes the risk of wrestling with this predicament. Rosenberg’s critical method asserts the value of relativism: “The first requirement of art criticism is that it shall be relevant to the art under consideration; how correct are its evaluations of specific art objects is of lesser importance,” he wrote in 1975. In emulation, Town’s purpose—when writing about artists as diverse as Albert Franck (1899–1973), Tom Thomson (1877–1917), and Picasso—is to open the viewer’s eyes to the artist’s stages of decision making, to unravel “the painting as a formal object set into dialogue with creative intentions.”

Rosenberg’s open-minded consideration of the great variety of new art movements gave permission to Town’s investigation of a plurality of styles. Town’s constant attention to the works of Old Masters as a measure of possibility and artistic attainment accords with Rosenberg’s view that “the density of meaning in a modern painting is always to some degree an effect of the artist’s engagement with the history of art, including ideas about it…. An historically ignorant painter has no better claim to attention than the ideas of an economist who never heard of the Stock Market Crash.”

Anticipating Postmodernism

The term “postmodern” has had no universally accepted definition, depending as it does on prior assumptions about the nature and meaning of the “modern” in art. Most broadly, it signals a number of breaks that artists made with the accepted norms of modern art practice during the 1960s. In Town’s case this was a turn away from the autonomy and strictly formal concerns prescribed by Clement Greenberg. Town brought a gamut of external reference into his paintings, drawing on the worlds of the city and its museums.

Since Greenberg’s doctrines were by then widely accepted in Canada, Town’s combination of eclectic sources appeared to curators and critics as self-indulgently eccentric. With his 1962–64 series, the Set paintings and Tyranny of the Corner paintings, Town engaged in a new area of investigation, adjacent to that of the Pop art movement but in a more abstract vein. Using tools of appropriation, irony, and humour, he highlighted the artificial nature of sign systems and art styles, and the random ways in which signs collide and coexist in the contemporary environment.

The term postmodern was not available when Town made these series, but comparisons with later artworks that define the category show that Town was indeed entering this new frontier. For example, the paintings of Carroll Dunham (b. 1949) in the 1980s and those of Lydia Dona (b. 1955) in the 1990s combine drawn and painted elements from diverse visual worlds, including comic books, drawings of machine parts, decorative patterns, and abstract design elements. These elements collide in an open space that seems unbounded by the canvas while they are held to its surface by their identity as painterly marks. Town’s 1962–64 paintings likewise combine elements taken from bewilderingly different symbol systems—maps, Asian character writing, or patterns of electronic circuitry, as in Tyranny of the Corner (Sashay Set), 1962.

Town’s anticipation of postmodernism can be seen again in his idiosyncratic response to the international Op art movement that became a sensation in New York with the Museum of Modern Art’s 1965 exhibition The Responsive Eye. In a painting like Festival, 1965, the effects of layering, the implied continuation of the organic elements beyond the frame, and the sheer technical intricacy of interwoven elements move into a postmodern celebration of excess.

When Town brought figurative images back into his canvases in 1980, he was following in the wake of Philip Guston (1913–1980), who rejected modern abstraction. Rosenberg’s defence of Guston—“Painting needs to purge itself of all systems that place so-called interests of art above the interests of the artist’s mind”—was one that Town might have claimed as his own.

Legacy

Town did not surround himself with disciples or followers. Although friends found him generous and charming, as an artist he was highly competitive and spent vast amounts of time alone in the studio. He did directly mentor one emerging artist, Landon Mackenzie (b. 1954), whose grandparents lived across the street from Town on Castle Frank Crescent. Town was a close friend of Mackenzie’s parents and particularly of her mother, Sheila, who hosted late-night parties at which Town and others held court until dawn. Mackenzie acknowledges the vivid impression his art left on her. Her first body of work, a series of diaristic monoprints in 1977, was done with Town in mind. She received her copy of Town’s retrospective catalogue with the inscription “To my one and only pupil.” Other artists of the postmodern generation who have expressed interest in his work include Brian Boigon (b. 1955), Oliver Girling (b. 1953), Cliff Eyland (b. 1954), Michael Davidson (b. 1953), and Eric Glavin (b. 1965).

Town may be compared in some respects to philosopher Marshall McLuhan: both rejected a narrow disciplinary focus, incorporating in their creative horizons the worlds of historical “high” culture, avant-garde experimentation, and popular media production. Both fell from a peak of extraordinary success to temporary oblivion. McLuhan’s prophetic mapping of postmodern culture is now widely acknowledged, while Town’s legacy is currently being reassessed.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements