Harold Town (1924–1990) was a brilliant figure in Canadian art from the 1950s to the 1980s. A founding member of the Abstract Expressionist group Painters Eleven, Town went on to explore a variety of media and styles. International acclaim for his 1950s prints was followed by Toronto shows where his paintings fetched record prices and ignited a new local art scene. From the late 1960s Town fell from critical favour but continued to produce trail-blazing work.

Early Years

Harold Town’s artistic career was shaped by the rapid postwar development of his hometown, Toronto. The physical and social environment of that city—and the conditions it offered for the exhibition, sale, and reception of his art—are key to understanding the shifts in his production and in his reputation.

Town was born in Toronto in 1924 and grew up in the west end, in the Village of Swansea, where his father worked as a railway conductor. From childhood he was obsessed with drawing; his mother allowed him to use the enamel-topped kitchen table as his canvas. As a student at Western Technical-Commercial School, Town specialized in art, and his imagination was fired by studies of Renaissance art history and the Old Masters. He attended the Ontario College of Art (OCA; now OCAD University) from 1942 to 1944 but found the teaching there uninspiring.

As an OCA student Town received free admission to the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). He felt challenged by the achievements of great artists of the past. At age twenty he could emulate the work of Edgar Degas (1834–1917), though with a contemporary twist, as exemplified in his work Seated Nude, 1944. He resolved to master every aspect of figure drawing by the age of thirty.

The Royal Ontario Museum was an even greater source of inspiration. Town marvelled at the Oriental prints and ceramics, the grandeur of the Mesopotamian and Egyptian antiquities acquired by archaeologist C.T. Currelly, and the suits of European and samurai armour. This exposure gave him what he came to see as a global horizon, and it inspired his work as a commercial artist and his first experiments in abstraction.

In his early painting Don Quixote, 1948, the knight is shown mounted on his rickety steed and compressed into a shallow faceted space, as Town riffs on both Cubism and the decorative patterning of European armour. In contrast, his early monoprint Soldier Leading Horse, 1953, renders a classical heroic subject with extreme simplicity and deliberate naivety, showing Town’s early grasp of the expressive potential of diverse styles.

Town’s work was inspired by his interest in the historical and the literary, but throughout his career he also drew on interests developed during his Toronto boyhood: the intertwining of industry and nature in the Toronto landscape; comic books (he landed a summer job at Double A Comics but was dismissed for adding too much detail in his drawings); and the cinema, where his job as an usher left him a passionate film buff.

Career Start

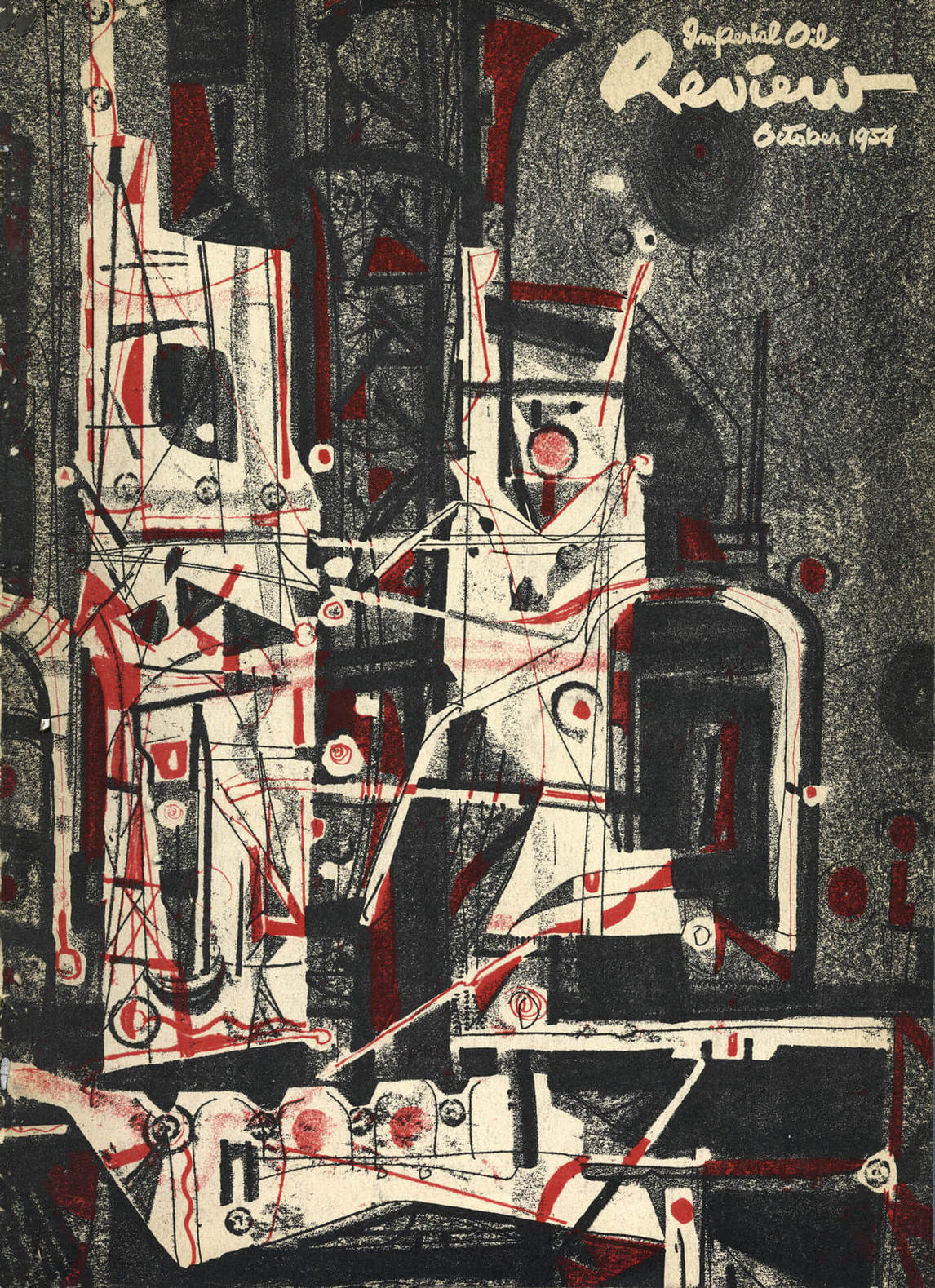

Town began his artistic career in commercial illustration, as many artists did at the time. He credited it with instilling a discipline that would sustain his whole artistic production. In commissions from Imperial Oil, he transformed the company’s oil refineries into abstract images; in 1954 he was interviewed by the Imperial Oil Review for his views on contemporary abstraction. Through this commercial work he became a close friend of Oscar Cahén (1916–1956), an artist of German and Jewish extraction who had trained and worked in Dresden, Prague, and London and who, after wartime deportation to Canada, became known as one of the country’s best illustrators. Another important early mentor was Albert Franck (1899–1973), an older immigrant artist from Holland who painted scenes of Toronto’s back lanes. Franck’s job as a picture framer at Eaton’s College Street Fine Art Gallery allowed him to help Town and other emerging artists by placing their work in shows at the gallery.

By the early 1950s the wider world of modern art was at last reaching Toronto. A large survey exhibition in 1949 at the Art Gallery of Toronto, Contemporary Paintings from Great Britain, France and the United States, included the semi-abstract images of Britain’s neo-Romantic painters like Graham Sutherland (1903–1980) and current work by New York’s Abstract Expressionists. Canadian artists Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) and Alexandra Luke (1901–1967) were bringing the teachings of Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) to their colleagues, and individual experiments with abstraction were set to coalesce into a local movement.

Painters Eleven

Town would play an important role in Toronto’s emerging Abstract Expressionist movement, coining the name of the group Painters Eleven for their first show at the Roberts Gallery in 1954. The initiative to organize this heterogeneous, cross-generational group, which united to demand serious attention for abstraction in Ontario, came from Alexandra Luke and William Ronald (1926–1998). However, it was Town who wrote the statements for their catalogues. When Ronald moved to New York in 1955 and in 1957 resigned from the group, Town became the leading artist among Painters Eleven in terms of international and museum recognition for his work.

Town’s first success came with an innovative form of monotype that he developed in 1953, which he called “single autographic prints.” These prints caught the eye of gallery owner Douglas Duncan, who presented Town’s first Toronto solo show at the Picture Loan Society in 1954. Two prints were immediately acquired by the National Gallery of Canada. In 1956 three more prints were acquired by the Art Gallery of Toronto, and the National Gallery chose Town’s single autographic prints to represent Canada at the 1956 Venice Biennale, alongside paintings by Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) and sculpture by Louis Archambault (1915–2003).

Town was also quickly acknowledged in Montreal, being offered a solo show in 1957 at Galerie L’Actuelle, recently opened by Guido Molinari (1933–2004). As home of the Automatistes, Montreal had already produced a succession of abstract movements, and Town’s favourable reception there would continue throughout his career.

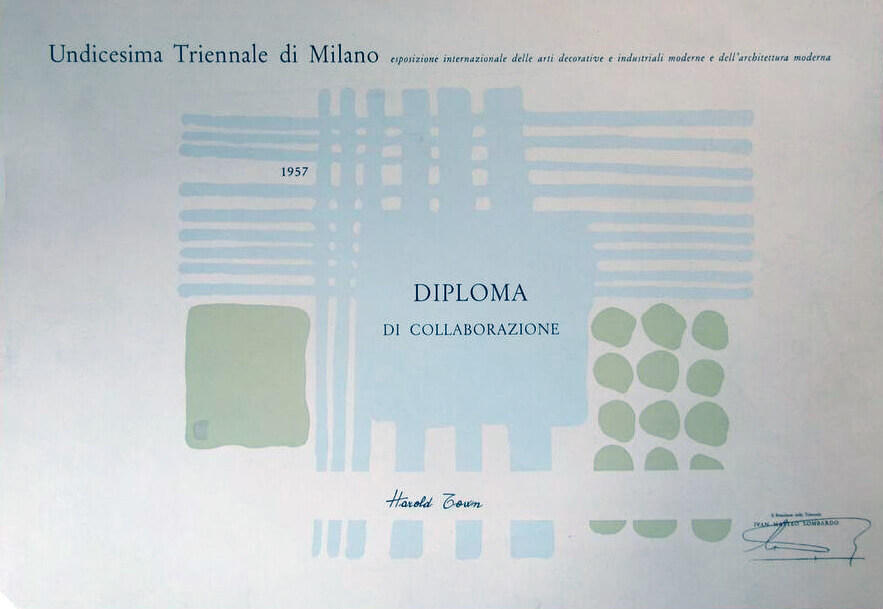

The National Gallery included Town’s works in other international exhibitions—in the Smithsonian Institution’s Canadian Abstract Paintings show that toured the United States in 1956–57, and in 1957 the Milan Triennale, the Ljubljana International Print Biennale (which awarded him an honourable mention) and the Bienal de São Paulo (where he won the Arno Prize for graphic art). By 1957 he had had solo painting shows in Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal, and he was invited to show with Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) at the Arthur Tooth & Sons Gallery in London, England.

That same year William Ronald arranged for the influential New York critic Clement Greenberg to visit Toronto and give studio critiques to the members of Painters Eleven. Town and his friend Walter Yarwood (1917–1996), another member of the group, declined to contribute toward Greenberg’s expenses; Town saw no need for Greenberg’s counsel. He wrote of abstract art in the 1957 Painters Eleven catalogue: “Painting is now a universal language; what in us is provincial will provide the colour and the accent; the grammar, however, is part of the world.” His horizons, he believed, were already international, and he was determined to prove that significant new art could arise in Toronto.

The St. Lawrence Seaway Mural

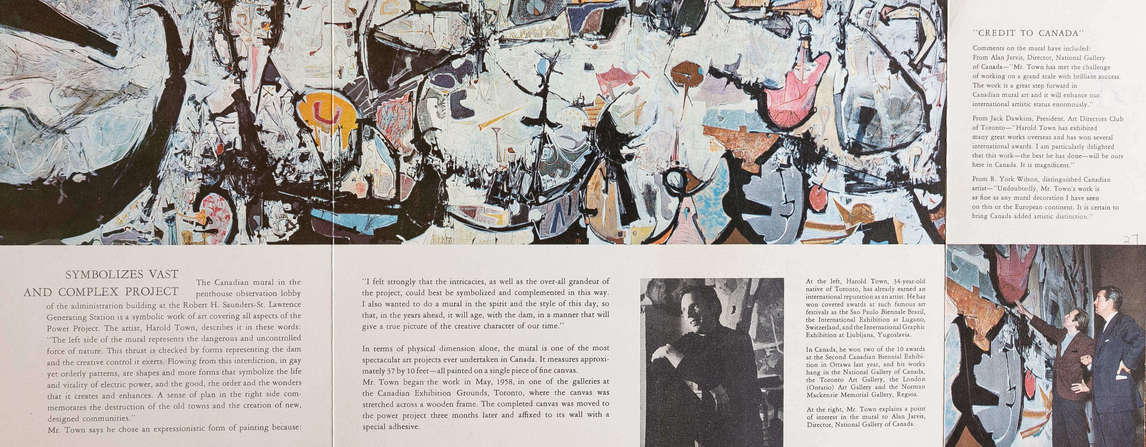

Town’s career escalated as Toronto transformed into a modern city. In 1958 the ultra-modern design by Finnish architect Viljo Revell (1910–1964) was selected for the new city hall. Architect John C. Parkin (1922–1988)—who worked on the construction of Toronto City Hall and, during the 1960s, on the Toronto-Dominion Bank towers designed by Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969)—led younger Toronto architects into international modernism. Public and corporate-sponsored art was on the rise. Nevertheless, in 1958 it was a startling coup for the thirty-four-year-old Town to win the commission for a large mural (3 x 11.3 metres) for Ontario Hydro’s Robert H. Saunders Generating Station on the St. Lawrence Seaway at Cornwall.

Town threw himself into the challenge with élan, creating bristling mechanical forms and scooping curves that drew on his observations of work at the site. The mural symbolizes the clash between the forces of nature and the human intellect in “the bold remaking of a piece of the earth in Canada,” as reported by Pearl McCarthy, art critic of the Globe and Mail.

Newspapers published photographs of Town leaping into the air to apply paint to this vast canvas, like some reincarnated Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), while Liberal MPP Arthur Reaume ensured the mural’s notoriety by protesting the $10,000 price tag. Town’s mural exemplified Canada’s ability to generate a heroic, locally engaged Abstract Expressionism—a radical departure from the well-groomed elegance of the figurative murals by York Wilson (1907–1984), such as those commissioned for the foyers of the Imperial Oil Building (1957) and the O’Keefe Centre for the Performing Arts (1959–60).

A Modern Art Scene for Canada

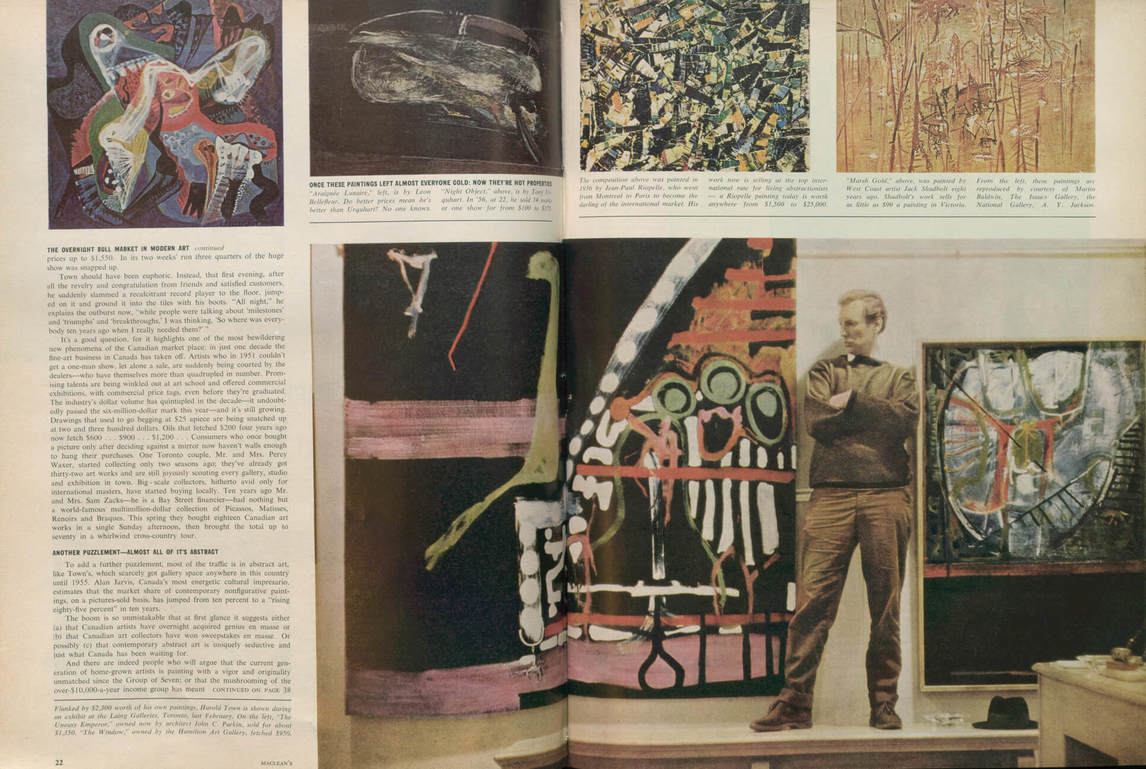

By the late 1950s the growing concentration of wealth in Toronto set off a local art boom. The members of Painters Eleven, with their bohemian lifestyles, had delivered a jolt to their famously dull and puritanical hometown. Openings at art galleries drew large, socially mixed audiences and regular press commentary. New dealers were emerging, willing to show young experimental artists and groom upcoming local art patrons. Barry Kernerman, whose Gallery of Contemporary Art lasted for four years, gave Town his first solo painting show in 1957. Helene Arthur, with her Upstairs Gallery (later the Mazelow Gallery), the venerable Laing Galleries, and Jerrold Morris, who opened the Jerrold Morris International Gallery in 1962, would each hold a stake in Town’s work.

Lively interest in abstract art was spreading across Canada, generating debates on the relative merits of the art scenes in Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver. The Biennial Exhibition of Canadian Painting, initiated at the National Gallery in 1955 with the appointment of Alan Jarvis as director, was an arena for such competitive jostling. Town’s work was prominent there and also at various American biennials and international shows to which the National Gallery sent Canadian selections. A high point came in 1964, when Town was invited to represent Canada for a second time at the Venice Biennale and was selected as one of 361 leading world artists by the curators of Documenta 3 in Kassel, Germany.

Toronto Celebrity

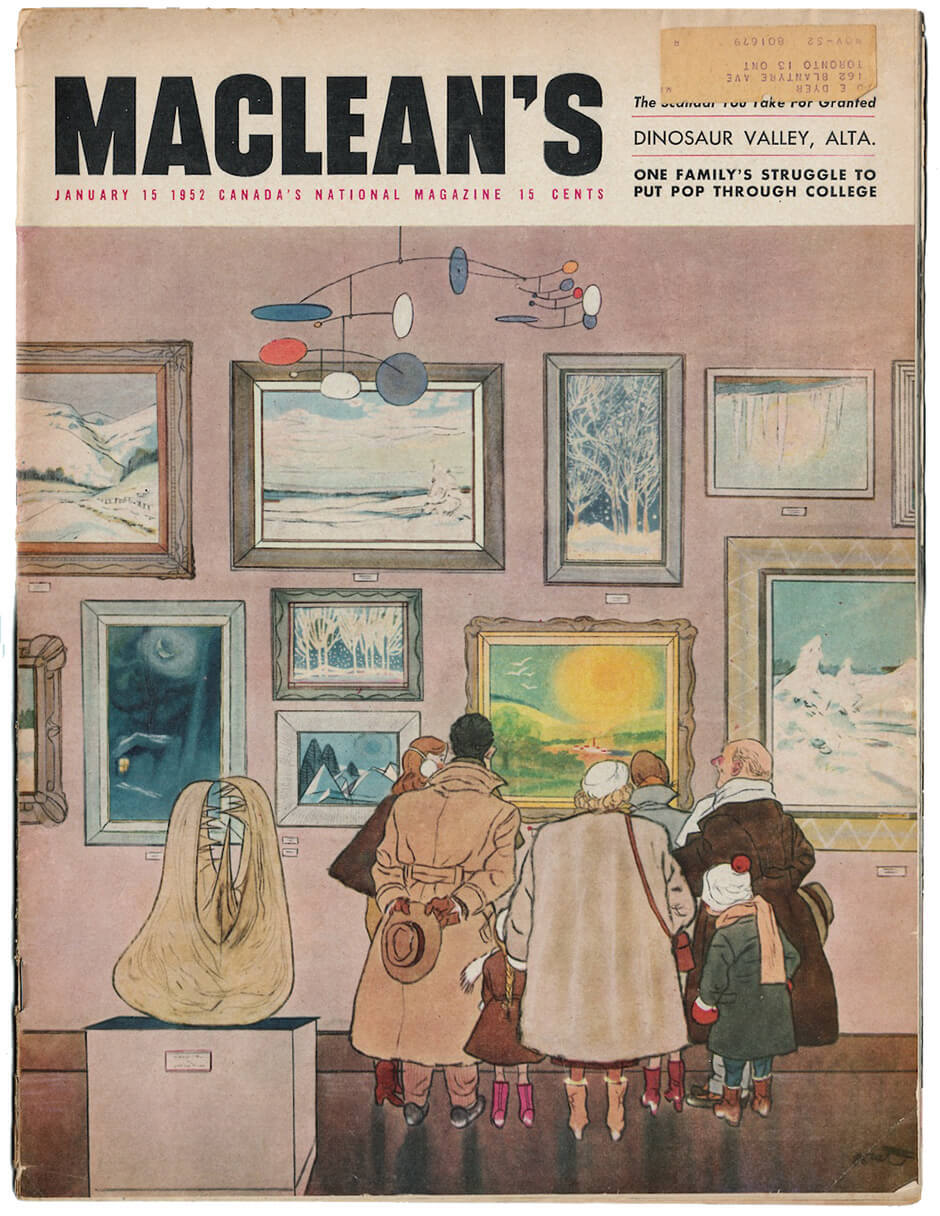

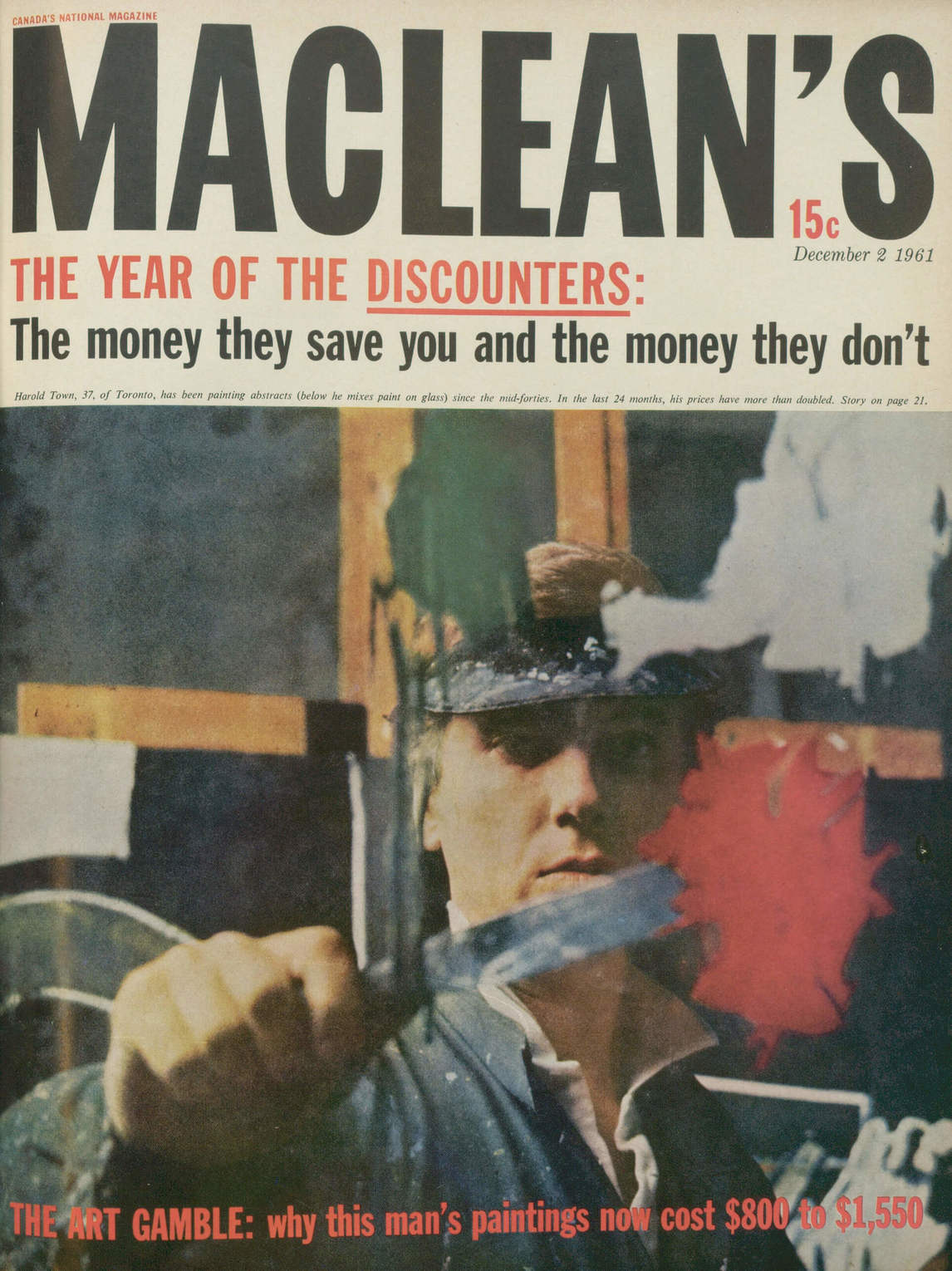

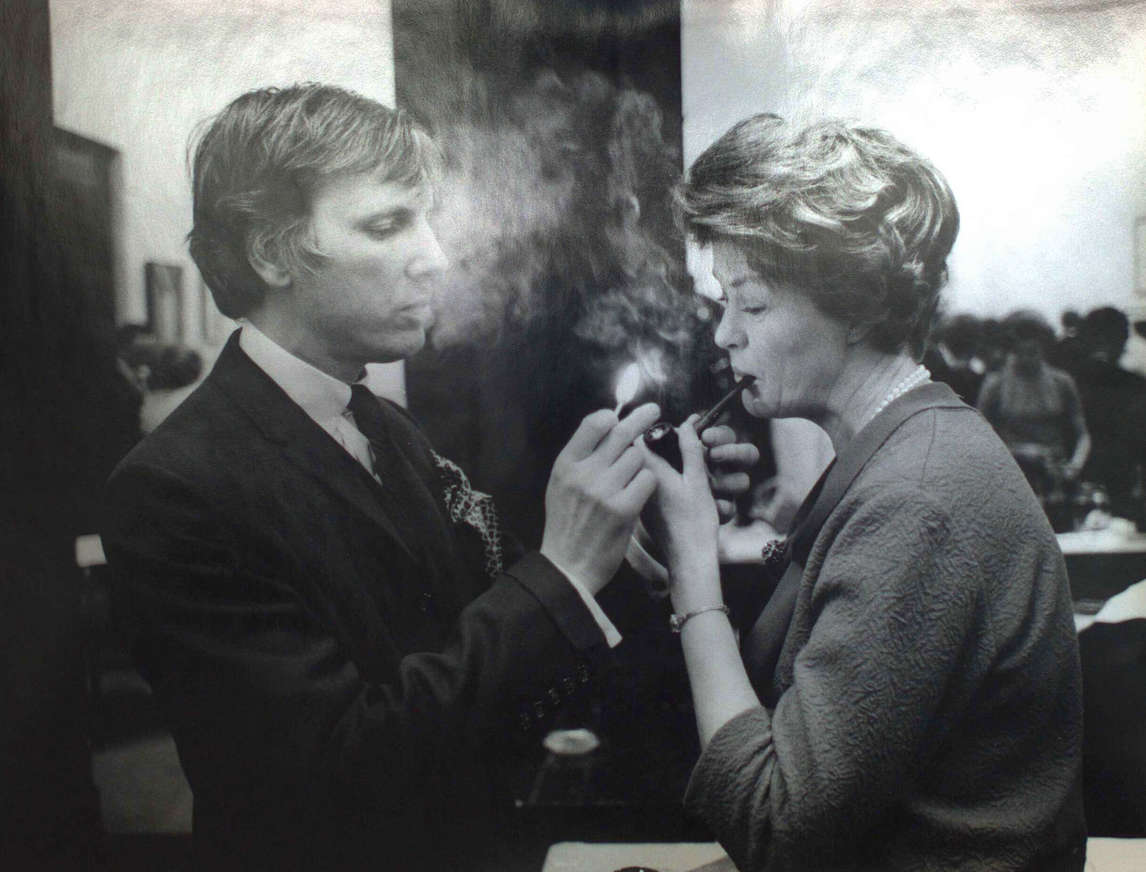

In 1961 Town had made the cover of Maclean’s, and the following year the Toronto Telegram Weekend Magazine carried a two-part feature by his friend Jock Carroll, which included anecdotes about Town’s outrageous exploits. When Town’s work was shown in Europe in 1964, he became a local hero at home.

The press was fascinated both by his notoriety as a dandy and party animal and by his reputed earning power as “the hottest sales property in English-speaking Canada. By 1965 his large canvases were fetching up to $4,000, a record price for contemporary Canadian work, and he was dubbed the “artist with a tax problem. In 1969 he was on the cover of the Canadian edition of Time magazine. Throughout the decade he was referred to as “synonymous with art in Toronto” or “Canada’s most famous artist.”

Town’s success could not have happened had he not been prodigiously talented, hard-working, and motivated. He spent days and nights in his studios, producing an expanding range of works in different media: ever larger canvases, collages that expanded on the style and ideas explored in his single autographic prints, and successive new series of prints and drawings.

His large canvases of the early 1960s precipitated frenzies of acquisition by corporate and private patrons, first at the Laing Galleries in 1961 and then at Town’s famous double openings in 1966 and 1967, when he launched distinct bodies of work simultaneously at the Mazelow Gallery and at the Jerrold Morris International Gallery. Young newspaper critics found his work exciting to decode, and Robert Fulford and Elizabeth Kilbourn became keen champions, reviewing his shows and contributing exhibition catalogue essays. Town rented a second studio unit in the historic Studio Building, at 25 Severn Street, which Lawren Harris (1885–1970) helped build for the Group of Seven.

In 1961 Town became an established member of Toronto’s cultural elite when he was invited to join the exclusive (and oddly spelled) Sordsmen’s Club. Defined in its charter as “devoted exclusively to the pursuit of pleasure, superb food, fine wine, exceptional women, and conversational excellence,” the club was limited to fifteen permanent members, including author and broadcaster Pierre Berton, publisher Jack McClelland, architect John C. Parkin, Alan Jarvis (then editor of Canadian Art magazine and national director of the Canadian Conference of the Arts), and CBC TV producer Ross McLean. Through the Sordsmen he made close and influential friendships that generated invitations to publish newspaper columns, create art books, and appear on radio talk shows and in TV interviews.

With his sharp wit, conversational skills, and wide reading, Town defended abstract art in the face of Canada’s conservatism, wrote book reviews for the Globe and Mail, and contributed a regular cultural column to Toronto Life magazine during 1966–71. He became engaged in the conflicts that attended the rapid pace of urban development. Town supported Mayor Phil Givens, who led the public fundraising campaign to purchase the sculpture by Henry Moore (1898–1986) now in front of City Hall and acquired contemporary Toronto canvases for the building’s interior (a large Town was hung behind Givens’s desk). He protested against the inroads of the automobile and the destruction of Toronto’s historic buildings; he contributed posters for the 1969 campaign opposing the Spadina Expressway and for reformer David Crombie’s 1972 mayoral campaign and bid to save Toronto’s neighbourhoods.

Town cherished his own Toronto neighbourhoods: the Swansea of his boyhood, the Gerrard Street Village of his fledgling artist days, and finally South Rosedale. In 1961 he established a family home at 9 Castle Frank Crescent with his wife, Trudie, a librarian. Town’s daughter Shelley recalls that she or her sister Heather would phone their father when supper was nearly ready. (Town had home studios, but his larger studio on Severn Street was a short walk away through the Rosedale ravine.)

Town’s stock was still high in Canada in 1967 when his work was included in all the national centennial art projects of that year and he was awarded a Centennial Medal. He had been granted an honorary doctorate by York University in 1966 and was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1968. He was beginning to be framed as part of the establishment, a target for the barbs of a younger generation of artists. In 1968 Iain Baxter (b. 1936), under the pseudonym of his art collective N.E. Thing Co., exhibited Dark, Four-Handled Carrying Case for Harold Town’s “Optical” at the 7th Biennial Exhibition of Canadian Painting at the National Gallery, alongside works titled Bagged Rothko and Extended Noland.

Backlash

A gradual shift in Town’s reputation began in the mid-1960s. Developments in art and art criticism had moved away from the Abstract Expressionism within which his work had won international recognition. In 1964 the international reputation of fellow Painters Eleven member Jack Bush (1909–1977) was launched by Clement Greenberg, who included him in his exhibition Post Painterly Abstraction, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. At the same time, counter-currents that Greenberg did not favour, Neo-Dada and Pop art, were opening art into the worlds of new media and commercial production. Younger Toronto artists Michael Snow (b. 1928) and Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) spent most of the 1960s living in New York, partaking in the Pop art, Conceptual, and Minimalist movements there.

Canadian critics became anxious about the plurality of Town’s art practices—drawing, printmaking, painting, and even excursions into sculpture (he attended workshops in metal sculpture in 1960–61 and exhibited in Canadian Sculpture Today at the Dorothy Cameron Gallery in Toronto in 1964). Negative commentary began to focus on his policy of remaining in Toronto. When Town chose not to attend the Venice Biennale where his work represented Canada in 1964, critic Paul Duval accused him of cutting himself off from the greater art world.

A further rebuke came in 1970 from National Gallery curator Dennis Reid, who in an article discussed “the problem of staying in Toronto,” stating that the only continuing achievements by former members of Painters Eleven came from the two artists whose inspiration originated in New York: Jack Bush and William Ronald (1926–1998). This turned into an escalating dispute in the press, as Town, who was well read in the art criticism and debates of the time, lambasted the curators of the National Gallery and the Art Gallery of Ontario for what he saw as their subservience to New York fashions.

A Canadian Loyalist

Town was not unique in making an issue of loyalty to Canadian experience and, in his case, Toronto experience. Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) similarly refused to take his inspiration from abroad. He and Jack Chambers (1931–1978) in London, Ontario, were the leaders of a regionalist group that celebrated local landmarks and their own immediate lives, forging innovative styles to reflect on them. In Nova Scotia Alex Colville (1920–2013) imaged a realm of secluded, timeless truths. These artists offered recognizable figurative imagery of everyday, provincial worlds in Canada.

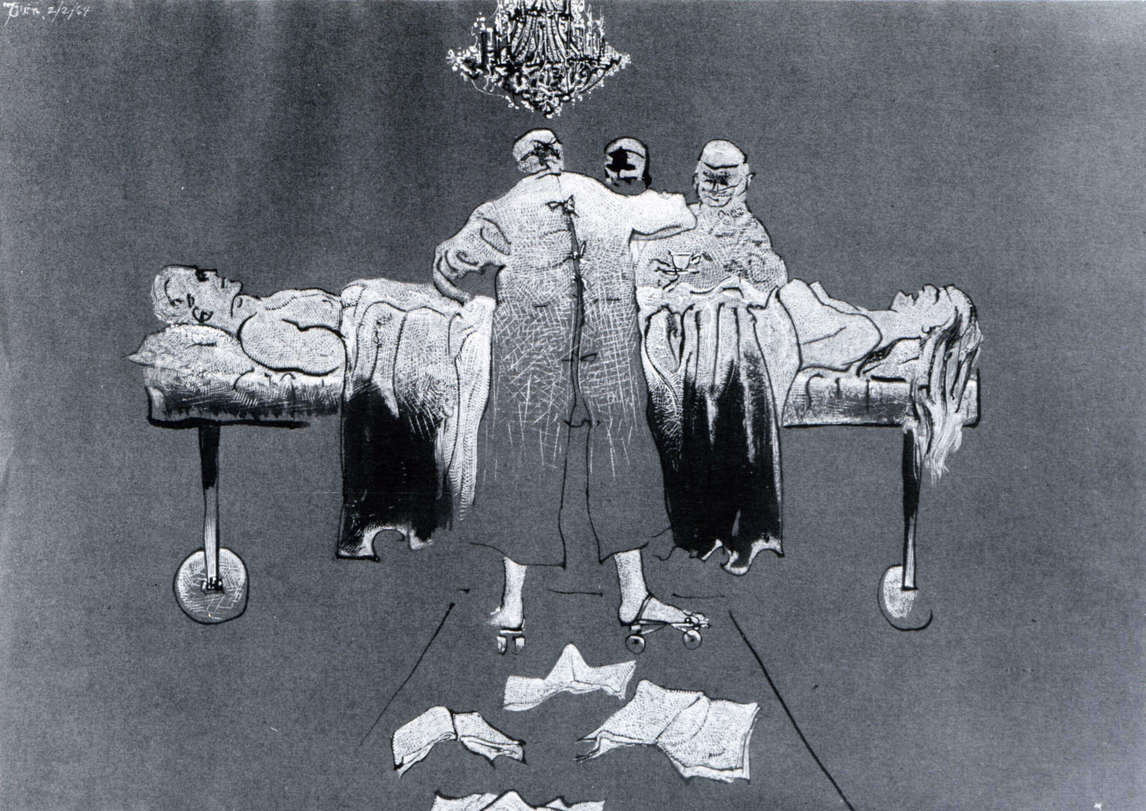

Town’s Toronto, however, was an emerging metropolis with all its attendant pretensions and excesses as a corporate and cultural centre. Town’s work addressed this environment in moods ranging between celebration, skepticism, and satire. He emphasized drawing as central to his inspiration—though this was not a medium considered central in the modernist hierarchy. In 1964 the exhibition of his Enigma drawings and their publication in book form aroused ambivalence: they demonstrated his indisputable mastery of a venerable medium but disturbed with their nightmarish satire of contemporary life.

As the 1960s waned, Town was aware that while other Canadian artists were beginning to win international notice, interest outside Canada in his own work was drying up. He continued to show his work abroad, but with diminishing success. With the dominance now of big-name critics and curators, and the plurality of new art movements, Town no longer played a leading role.

Seclusion and Retrospect

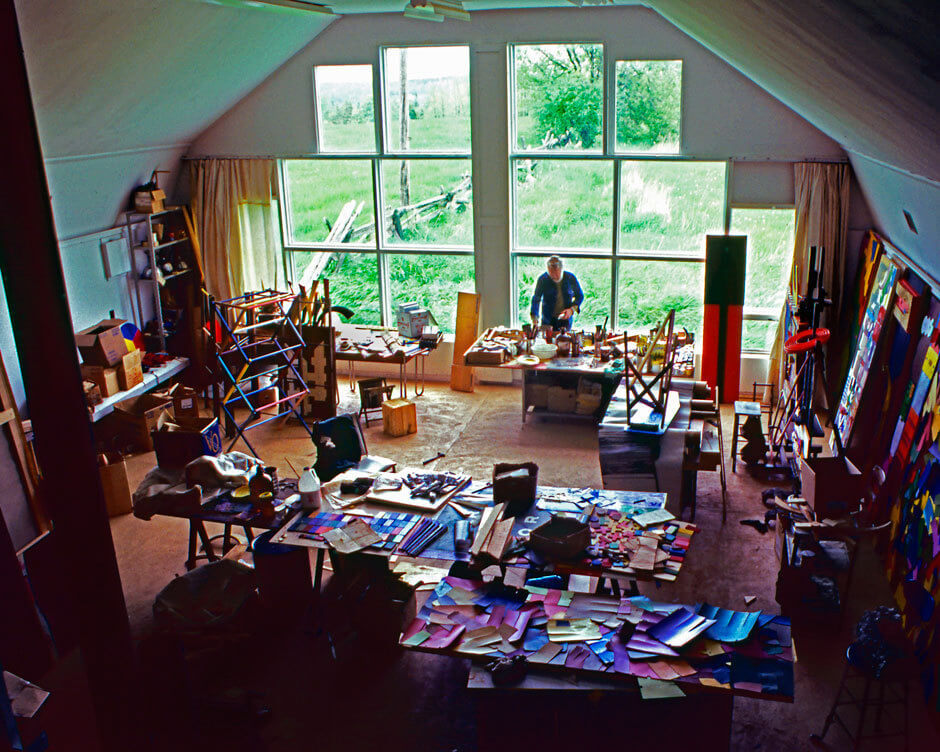

Town continued to produce large-scale painting series during the 1970s and 1980s, each time setting up a pictorial concept and strategy and exploring it through scores or even hundreds of works. He continued to receive press notice, to sell his work to a committed Toronto following, and to receive invitations to show in galleries across Canada.

Although his gallery launches now were less frequent, they were still calculated for dramatic effect. In 1969 a large retrospective show of drawings mounted by the Mazelow Gallery coincided with the publication of Robert Fulford’s book Harold Town: Drawings and toured to many Canadian cities the following year. In November 1970 his first painting exhibition in Toronto in three years—presenting the Silent Lights, Stretches, and Parks series—was held at the newly completed Ontario Place.

After another three years’ interval, the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa unveiled the Snaps series, some new Parks, and the Vale Variations at Harold Town: The First Exhibition of New Work, 1969–73. In the meantime Town fulfilled the 1960s dream of making his art available to a broad popular audience with the publication of a book of drawings, Silent Stars, Sound Stars, Film Stars (1971). His introduction was a witty analysis of the changing culture of cinema and of the way his generation had used the movies to fashion their identities.

As major Canadian museums gave retrospectives to Michael Snow and Jack Chambers (at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1969 and 1970, respectively) and major solo shows to N.E. Thing Co. and Joyce Wieland (at the National Gallery in 1969 and 1971), the omission of a Town retrospective was noted in the press. In part the slight was due to his own contrariness: William Withrow, director of the Art Gallery of Ontario, proposed a show to him in the late 1960s, an offer that was withdrawn when Town made it clear he expected control of the selection and presentation of the works. Town’s disputes with the curatorial establishment escalated when he insisted on choosing which of his works were to be shown in the National Gallery’s 1972 show Toronto Painting: 1953–1965, organized by Dennis Reid, and when he attacked that exhibition in the press for what he saw as its shortcomings.

Gary Michael Dault, in his review of a 1975 Town retrospective at the Art Gallery of Windsor, summed up the dilemma Town presented to a younger generation: “In order to think realistically about his art, you have to steer through his obsessive radio-active energy, his brilliant though sometimes hysterical writing, his memorable talk, his Byronic glamour, his defensiveness, and his Faustian belief in himself.

In 1976 Town purchased Old Orchard Farm, just outside Peterborough, Ontario. The large farmhouse and its outbuildings provided him with several studios—space to make large paintings, to experiment with assemblage and cut papers, and to store his collection of materials and ephemera. Town finally received a retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1986 but was dramatically absent from its opening owing to an operation for bowel cancer. The accompanying catalogue, by the show’s curator, David Burnett, was a substantial critical study. Unfortunately the exhibition itself was crowded with too many works, at Town’s insistence, and did little to revive his reputation within the art establishment.

Town continued to produce new work: his Toy Horse series, a painting series he called Stages, and a group of large abstract canvases he called Edge Paintings. During the 1980s he no longer had a regular Toronto dealer, and his shows were fewer. A rare major commission came to him in 1987 as part of the Cineplex Odeon Art Commission Program, impresario Garth Drabinsky’s project to place major works of contemporary Canadian art in movie houses. Town delivered a set of drawings of movie stills and two enormous canvases for the lobby of the Universal City Cinemas in Los Angeles.

In 1988 Town’s cancer returned, and he died in 1990. He was sixty-six. His death elicited tributes from newer supporters, such as Christopher Hume, and from stalwarts Robert Fulford and Pierre Berton, who wrote: “Town was a great artist with an insatiable intellect. Curator David Burnett indicated the challenge that Town’s legacy posed: “The heart of Town’s work does not lie in his response to Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s or, later, in his reaction against the numbing conformity of formalist abstraction…. Our response to his death must be to begin the process of understanding his achievement as a totality, of facing all of his work in the present.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements