Halifax has always been a difficult city for the arts to take root. Too often, just as a formative step was taken, a change of political or institutional leadership would derail a project, sending its proponents back to the starting line. In a province long seen internally and externally as a “have-not,” community leaders have often been reluctant to create and then support arts institutions, seeing them as luxuries in the face of other, more pressing concerns. An art school was first proposed for Halifax in the 1850s, and an art museum not much later, but it took generations of efforts by private citizens to create the institutions that Haligonians now enjoy. For many Nova Scotia leaders, the arts have been something the province can’t afford. A push for a building for the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts along with a new building for NSCAD failed in 1959; in 1985 a planned new build for the AGNS on the Halifax waterfront was cancelled; and in 2002 the arms-length Nova Scotia Art Council was disbanded. Both the AGNS and NSCAD continue to struggle with space challenges. Compromises have always been found; various levels of government have stepped up with support, and setbacks have been met with resilience by the institutions and their supporters. Both NSCAD and the AGNS have homes, less than optimal though they may be, and Arts Nova Scotia now ably serves the vital funding and promotion role once carried out by the Nova Scotia Arts Council. Despite the difficulties, the arts are firmly rooted in Halifax. For the community builders described here, and the numberless dedicated individuals whom they represent, the arts have always been exactly what Nova Scotia can’t afford to neglect.

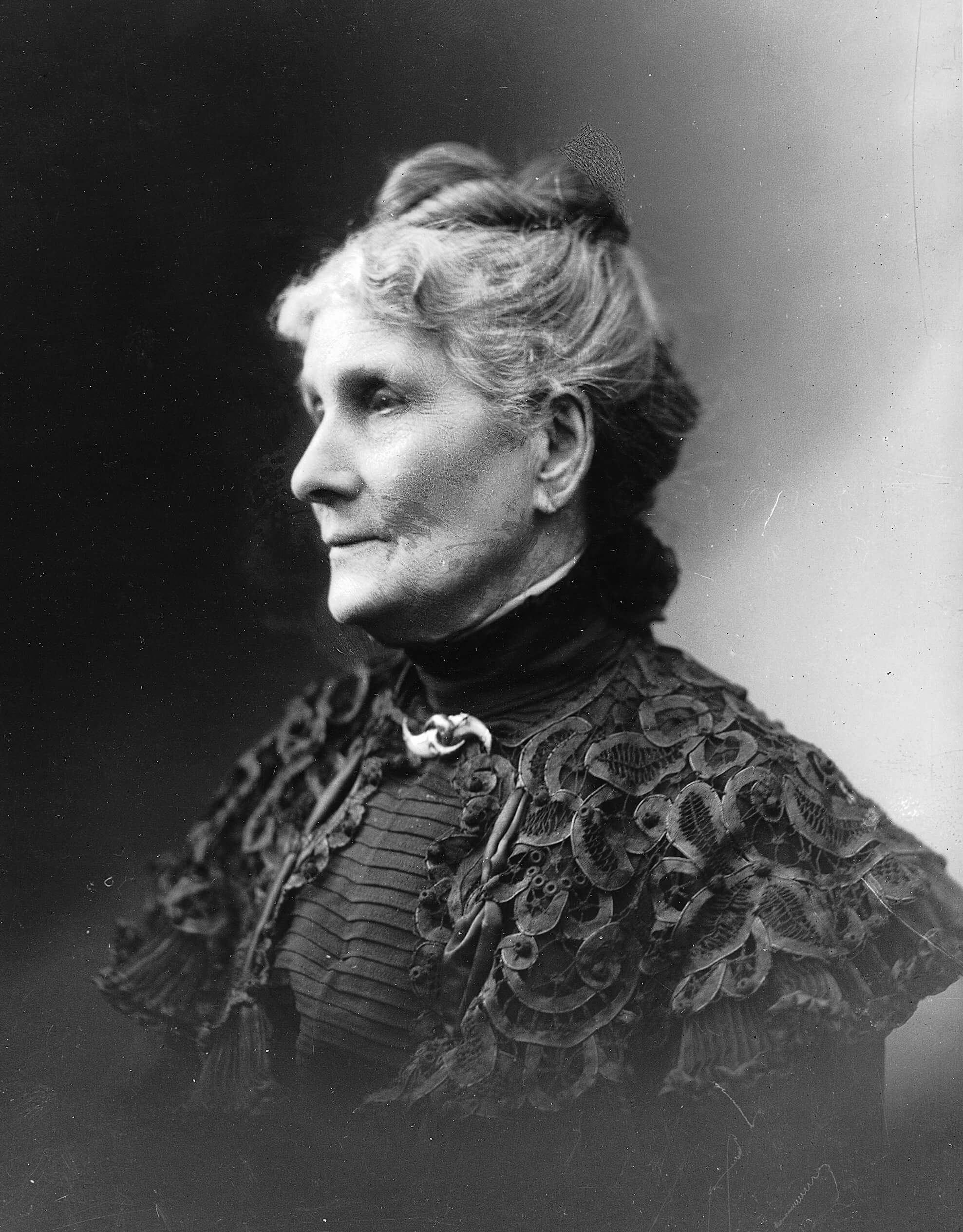

Anna Leonowens (1831–1915)

In 1876 a New York banker named Thomas Fyshe (1845–1911) accepted a job as manager of the Bank of Nova Scotia in Halifax. Once married, he moved his family there, which included his mother-in-law, a well-known author, lecturer, and educational advocate named Anna Leonowens. Fyshe may have made little impact on the art history of Halifax (the history of banking is another story), but Leonowens from her first year in the city played a major part in the effort to create an art school for Nova Scotia.

By the time she arrived in Halifax, Leonowens had had a rich and noteworthy life. In 1859 the newly widowed Leonowens opened a school for the children of military officers in Singapore. The school eventually came to the attention of the consul of the Kingdom of Siam, and in 1862 she was recruited to work for the royal family, first as a teacher and then as the language secretary of the King of Siam. She worked for the king for almost six years, then returned to England, but soon moved to New York. While in New York she wrote the first of several bestselling books, The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870). A fictionalized version of this book, Anna and the King of Siam by Margaret Landon, was published in 1944 and then adapted as the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I in 1951.

Leonowens was already a celebrity when she arrived in Halifax, and she immediately became involved in the life of the city, forming a book club and a Shakespearian society, as well as becoming active in the suffrage movement. Leonowens lent her skills as a lecturer and writer to promoting the cause of a new art school for Halifax, situating the cause within a larger North American movement and arguing for the benefits of “the establishment of schools of art and design, not only in encouraging the fine arts—such as painting, sculpture, architecture—but in giving a remarkable impetus and higher artistic value to all the branches of mechanical and industrial arts.”

She eventually became one of the three founding board members of the Victoria School of Art and Design (VSAD), opened in 1887 as part of the commemoration of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Her campaign in lectures and publications to promote the value of art education in Halifax had borne fruit: “Most people agree that the Victoria School of Art and Design was her idea,” one history of the art college notes.

Leonowens served as VSAD’s first vice-president and helped recruit their first headmaster, the British artist George Harvey (1846–1910). Her influence was felt in other ways as well: when the school first opened its doors it was housed on the upper floor of the Union Bank Building, the rental of which had been arranged by the bank manager, Leonowens’s son-in-law, Thomas Fyshe.

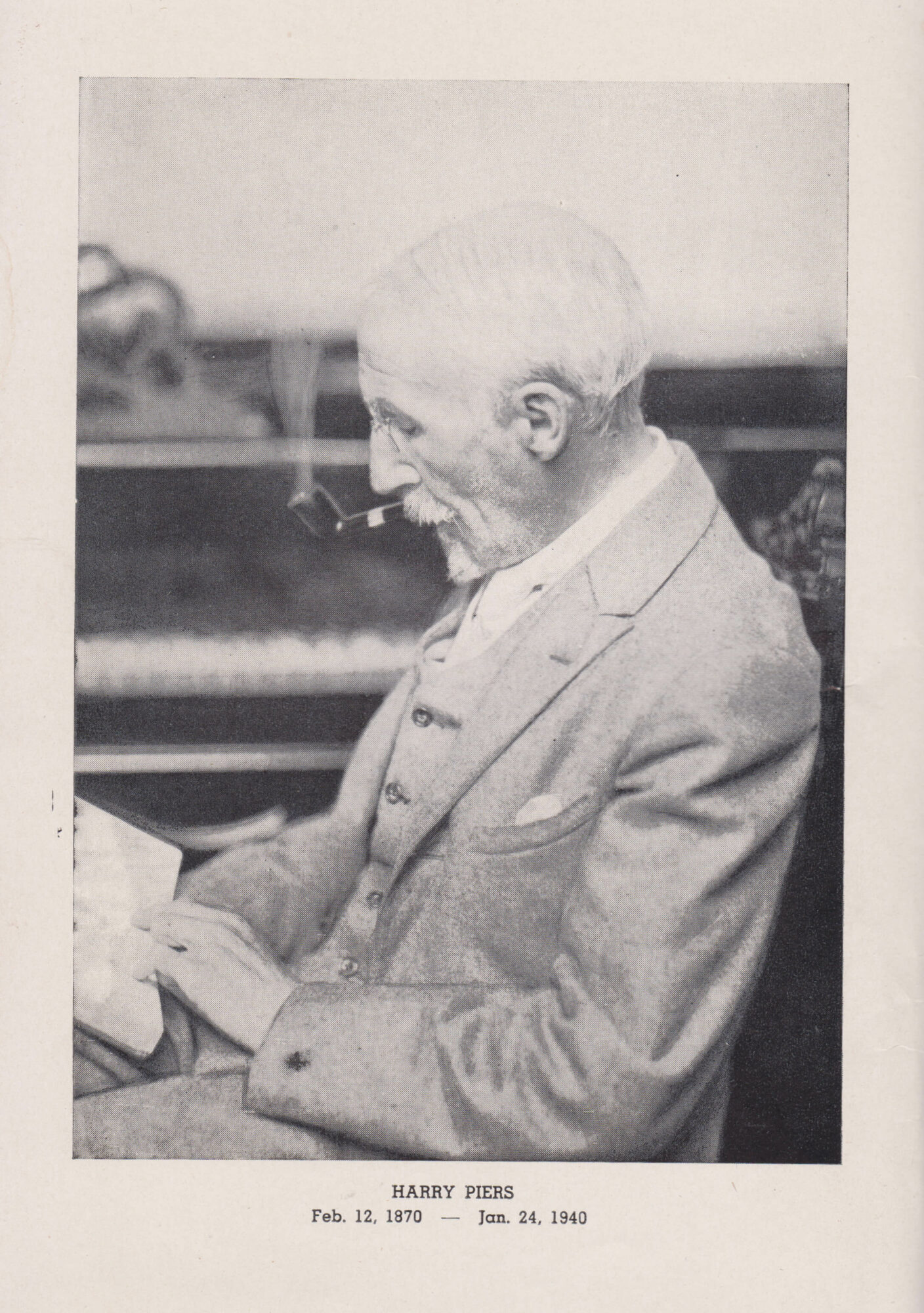

Harry Piers (1870–1940)

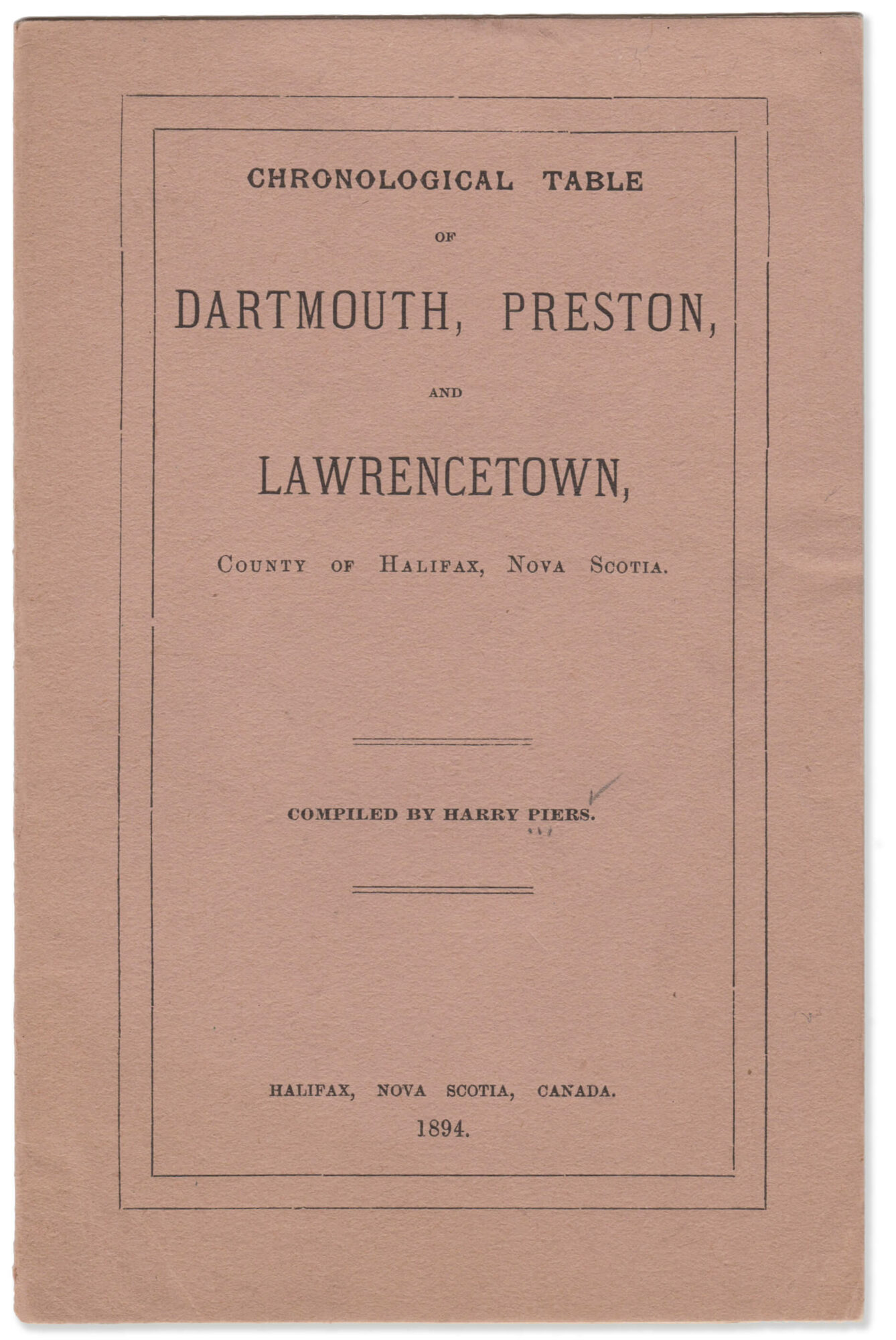

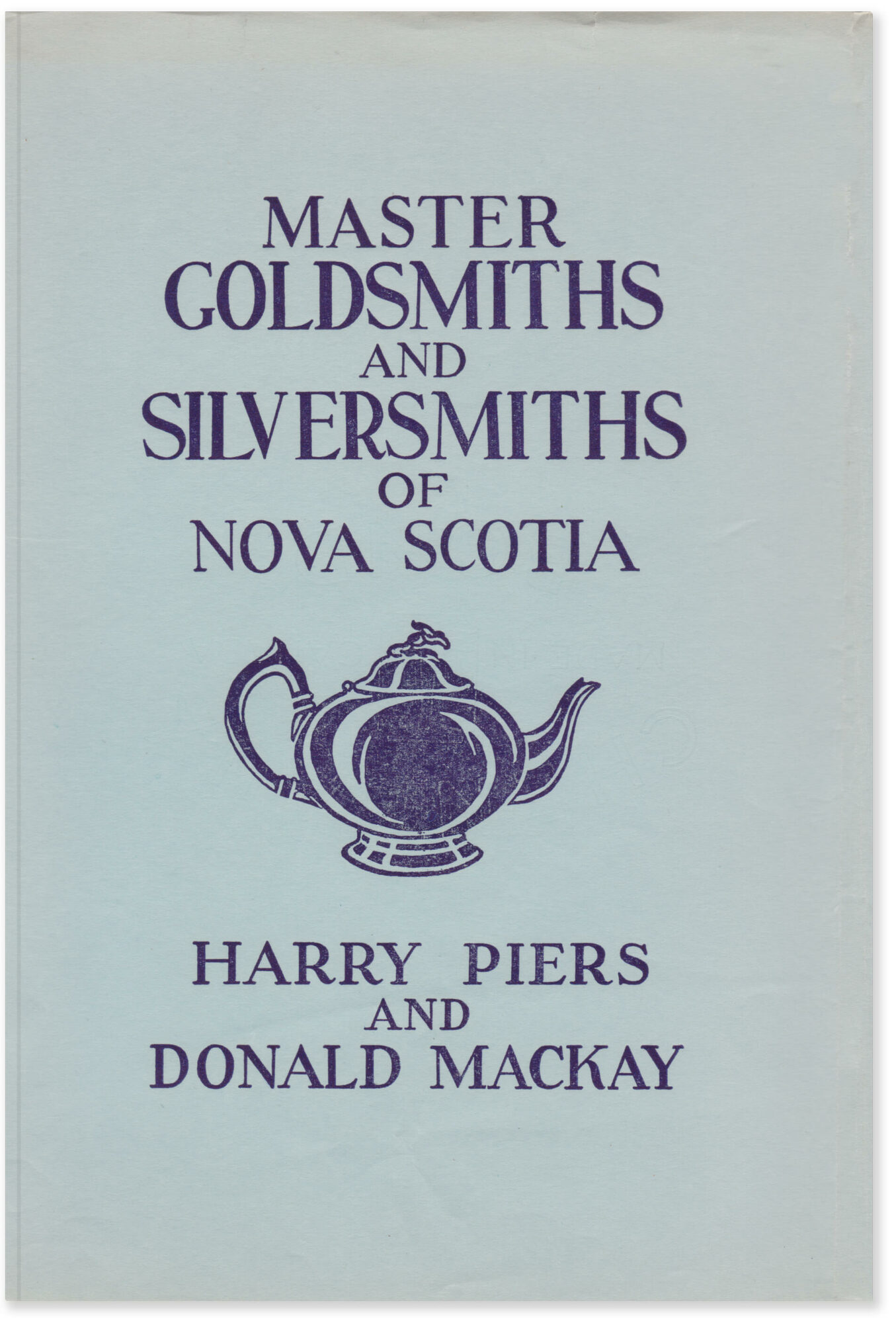

Harry Piers was a self-taught scholar who used his position at the Nova Scotia Museum to build a collection of fine art, Mi’kmaw artifacts, and other important objects of Nova Scotia’s material history. He became the province’s first art historian, writing an important work on Nova Scotia’s goldsmiths and silversmiths (published posthumously) and a study of the painter Robert Field (c.1769–1819). In 1914, in the Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, he published “Artists of Nova Scotia,” a listing of every artist—amateur and professional—that he could document working in Nova Scotia, from the founding of Port-Royal in 1605 to 1914. This listing remains the most comprehensive record of art activity in Halifax, and despite its numerous inaccuracies is used to this day by researchers. Piers’s collecting activities and his art historical research created the foundation for art historical study in Halifax.

Descended from a family that had come to Halifax with the original colonists in 1749, Piers, despite never earning a university degree, made an outsized impact on multiple fields of study: geology, botany, archaeology, military history, material culture, and art history. He was the author of numerous books on Halifax’s architectural and natural history, as well as important articles on the cultural history of the city and province. The Evolution of the Halifax Fortress, 1749–1928, his last book, which was published posthumously in 1947, has been credited as playing a key role in the decisions to preserve and restore the Halifax Citadel and York Redoubt.

Piers’s only formal education after graduating from high school was two years at the Victoria School of Art and Design, where he studied painting and architectural drawing in 1887 and 1888 (making him one of the art college’s first students). He also studied informally at the Nova Scotia Museum with its curator, David Honeyman (1817–1889). After Honeyman’s death Piers worked a series of short-term positions in libraries and archives in Windsor and Halifax until he was appointed Deputy Keeper of the Public Records of Nova Scotia in 1889, a government appointment that would last until the creation of the Public Archives of Nova Scotia in 1931. Later that same year he was named curator of the Provincial Museum (later the Nova Scotia Museum). In his first years at the museum he oversaw the move of the institution and its collections, including the public records collection, to a new building. Under the curatorship of Piers, the collecting mandate of the Nova Scotia Museum expanded from its natural history roots to include Mi’kmaw artifacts and oral histories, as well as material history collections and fine art and crafts. He was also appointed librarian of the newly created Provincial Science Library, which was housed in the same building. He held both positions until his death in 1940.

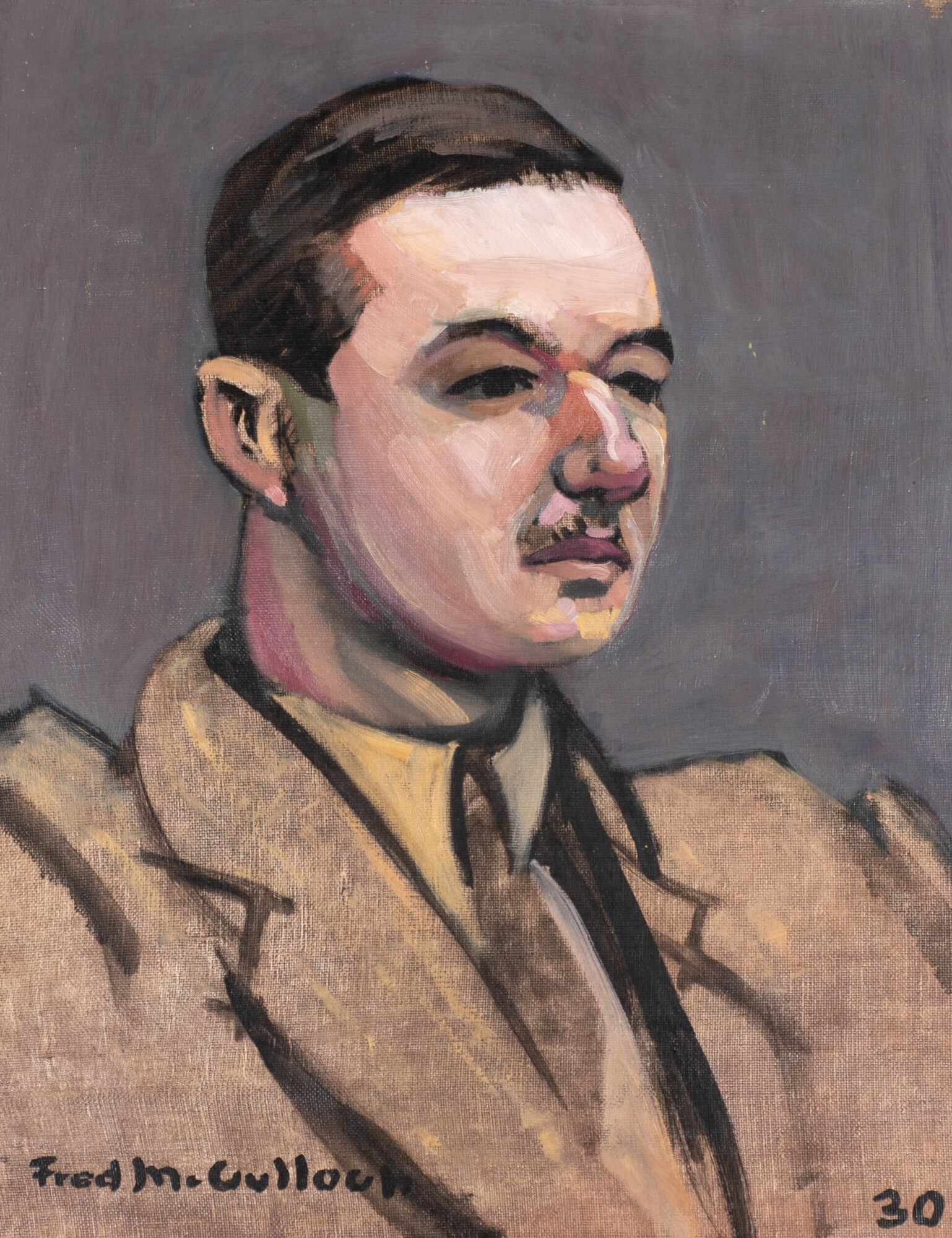

Donald Cameron (D.C.) Mackay (1906–1979)

Artist, educator, and art historian Donald Cameron (D.C.) Mackay played a central role in Halifax’s art history from the end of the Second World War (in which he served as a naval officer and an official war artist) until his death in 1979. He was a principal of the Nova Scotia College of Art (NSCA) and a professor of art history at Dalhousie University, as well as an active painter.

Born in Fredericton, New Brunswick, in 1906, Mackay studied at Dalhousie College and then at the NSCA, graduating in 1929. He then studied at the Chelsea School of Art in London and the Académie Colarossi in Paris before moving to Toronto, where he worked as an illustrator and did further studies at the University of Toronto with Arthur Lismer (1885–1969). He taught graphic arts at Northern Vocational School, and he eventually taught with Lismer at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario).

In 1934 he returned to Halifax to become an instructor at the NSCA, where he was named vice-principal in 1938. That same year he was appointed special lecturer in fine art at Dalhousie University, a position he held until 1971. He enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy in 1939, serving as an intelligence officer until his appointment as an official war artist in 1943. “The special quality of his work was the depiction of the sheer physical [effort] needed for the war at sea,” one historian noted.

Mackay was an active artist and a founding member of the Nova Scotia Society of Artists. But despite his art activities, “Mackay became what he had practised, despite his diversity: an administrator and educator.” In 1945 he was appointed principal and professor of art history of the NSCA, a position he held until 1967.

As NSCA principal, Mackay oversaw expanded enrolment and programs, including the creation of a three-year Art Education program in 1948. He also oversaw the purchase of the former St. Andrew’s United Church Hall, which was renovated into a modern building for the art college that opened in 1957. In an all too familiar pattern, the original plan had been for new construction that would have included a provincial art gallery, long a priority of the NSCA, the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts, and Mackay himself. Ultimately, the provincial government declined to support the effort.

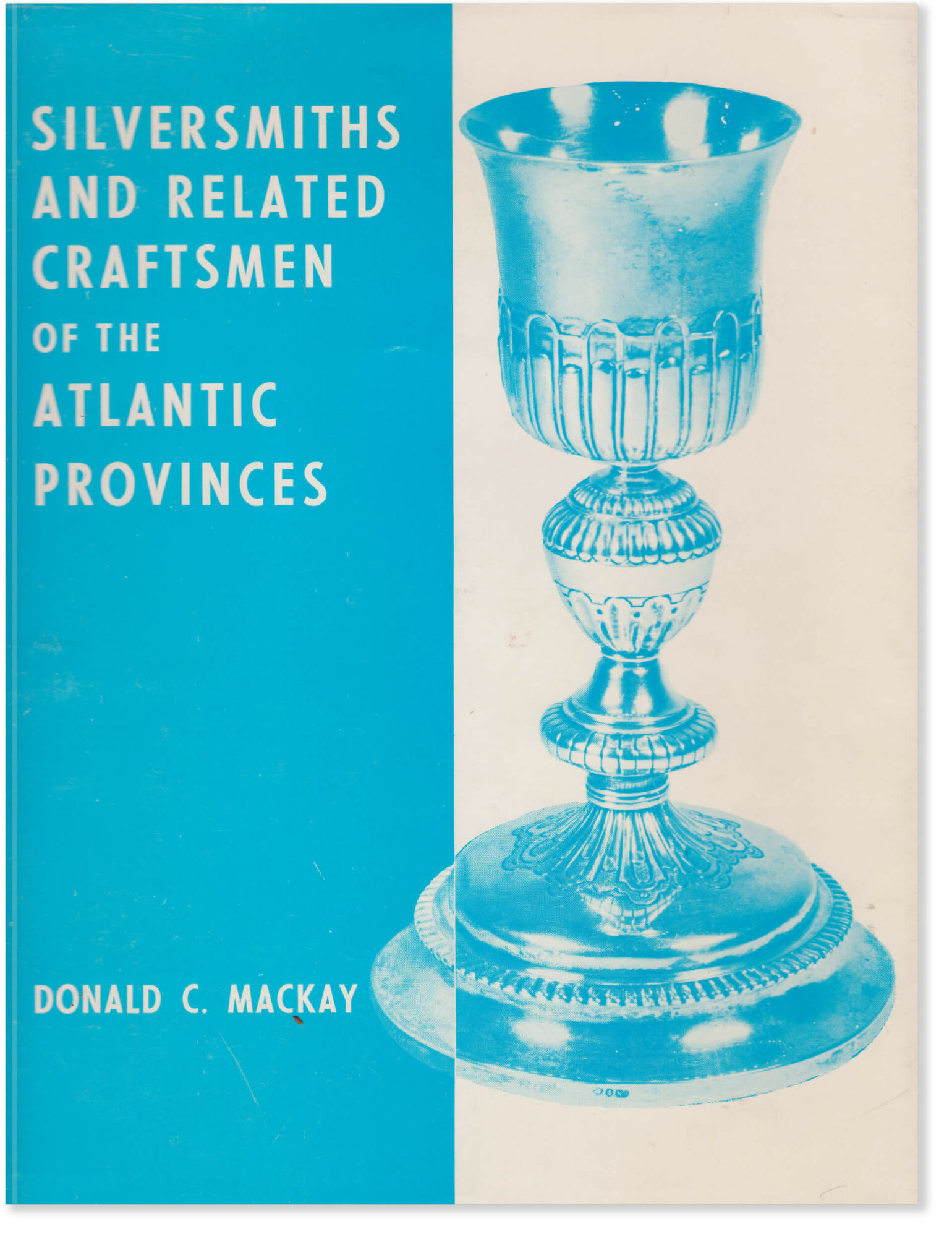

Mackay was one of Nova Scotia’s few active art historians throughout the 1940s, following in the footsteps of Harry Piers (1870–1940). In 1948 he edited and illustrated a book originally started by Piers, Master Goldsmiths and Silversmiths of Nova Scotia. In 1973 he published Silversmiths and Related Craftsmen of the Atlantic Provinces, and he spent the last decades of his life working on a monumental study, Portraits of a Province: 1605–1945 (which remains unpublished). In 1971 NSCAD awarded him the honorary degree of Doctor of Fine Arts.

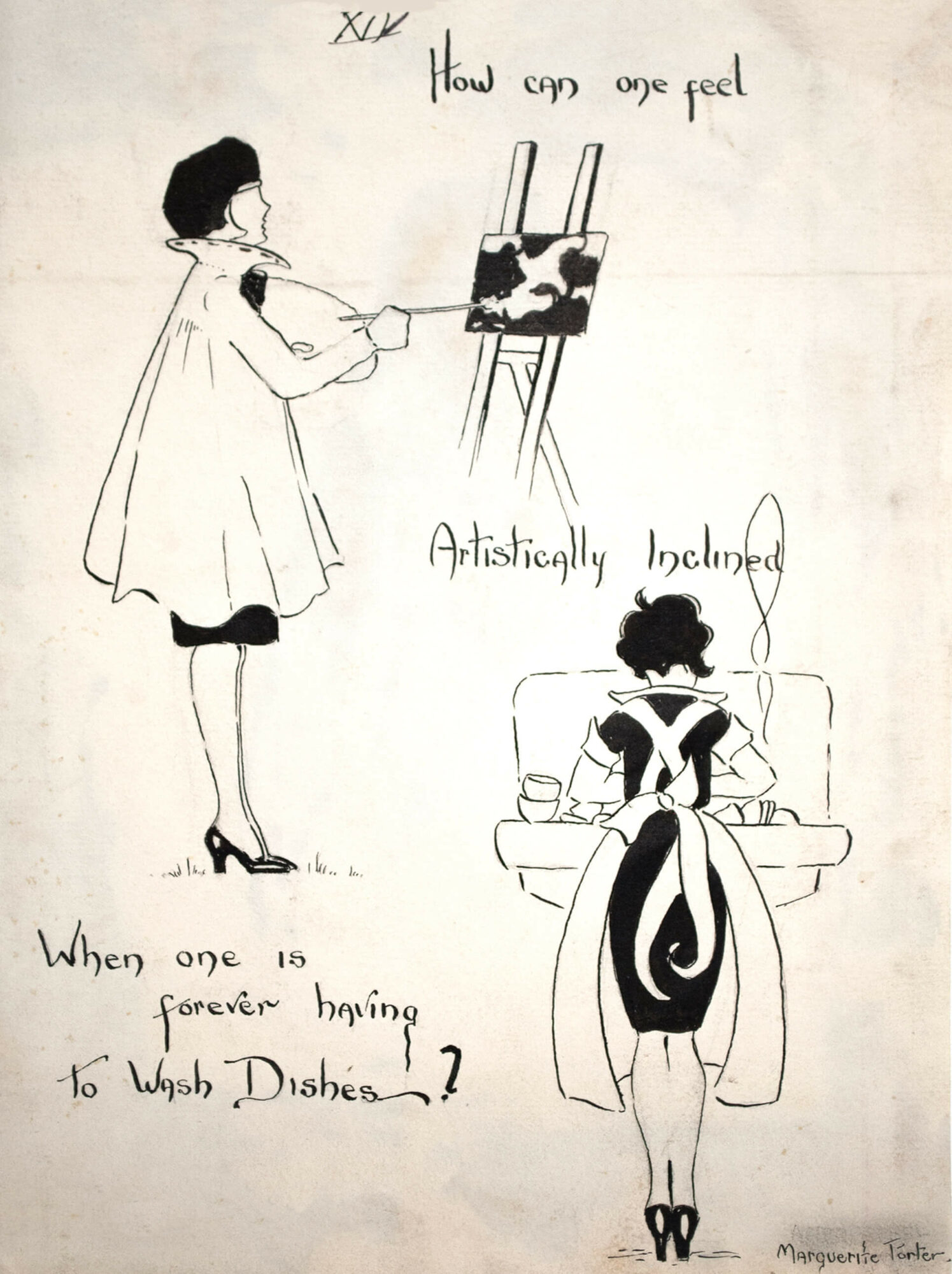

LeRoy Zwicker (1906–1987) and Marguerite Porter Zwicker (1904–1993)

Arts institutions in Halifax were built primarily through the efforts and financial support of concerned citizens. Two such committed individuals were the artists and gallerists LeRoy and Marguerite Zwicker.

LeRoy Zwicker was born in Halifax, scion of an esteemed Halifax merchant family that established what is the oldest commercial art gallery in Canada; in 1886 Zwicker’s father, Judson A. Zwicker, converted his wholesale glass firm into a store selling art and art supplies and providing framing services. When the elder Zwicker died in 1943, his son, LeRoy, a graduate of the Nova Scotia College of Art (NSCA), and LeRoy’s wife, Marguerite, took over running the shop and gallery. Marguerite was born in Yarmouth and had come to Halifax to study at the NSCA where she met fellow student LeRoy. They had married in 1938. Marguerite ran the day-to-day operations of the gallery, and LeRoy retained his job at Moirs chocolate company until the late 1950s.

The Zwickers ran the art gallery until their retirement in 1968. Both worked incessantly to create and sustain institutions that fostered artmaking in Halifax. They were founding members of the Maritime Art Association (MAA), for which LeRoy Zwicker served as business manager. LeRoy was also a regular contributor to the MAA’s magazine Maritime Art and to its successor, Canadian Art. Marguerite served as the magazine’s subscription manager and was active on the board of the MAA. Both were members of the Nova Scotia Society of Artists (NSSA). LeRoy served as president of the NSSA from 1938 to 1939, was on its executive council for many years, and in 1949 represented the NSSA on the organizing committee for 200 Years of Art in Halifax, an exhibition organized to mark the bicentennial of Halifax’s founding.

Both were also successful artists with active exhibition records who received professional accolades, including the prestigious Nova Scotia Artist status from the NSSA in 1939, the first year it was awarded. LeRoy Zwicker studied with Alfred Pellan (1906–1988) in the 1940s, and he was one of the few artists active in Halifax through that decade and the 1950s who explored abstraction in his work. When the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts moved into the former Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) building on Coburg Road in 1975 (shortly before becoming the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia [AGNS]), the inaugural exhibition in the space was LeRoy Zwicker: In Retrospect, a fifty-year survey of Zwicker’s work. In 1991 the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia mounted Marguerite Zwicker: Watercolours, a fifty-one-year survey of her work in her chosen medium.

LeRoy served on the board of governors of NSCAD in the 1960s, and in 1969 he received one of the first honorary doctorates in fine art conferred by the institution. In 1984 LeRoy and Marguerite Zwicker became the lead donors in the capital campaign that would lead to the creation of the first permanent home for the AGNS. Their $500,000 gift was accompanied by over sixty works of art and a library of art books. The Zwicker Gallery, now part of the AGNS’s First Nations Gallery, is named in their honour. Zwicker’s Gallery remains one of Halifax’s leading commercial galleries, operated by Ian and Anne Muncaster since 1970.

Garry Neill Kennedy (1935–2021)

In the late 1960s a small, provincial, and rather conservative art school in Halifax improbably rose to international prominence. That unlikely transformation was the product of an innovative, subversive, and highly successful effort led by Garry Neill Kennedy.

Kennedy was born in St. Catharines, Ontario, in 1935. From 1956 until 1960 he studied at the Ontario College of Art, earning a diploma in fine art. He earned a BFA from the University of Buffalo and completed a Master of Fine Arts degree at the University of Ohio in 1965. From 1965 until 1967 he was head of the art department of Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin. He was hired away by the Nova Scotia College of Art’s board of directors in 1967 to become the school’s first president, at the age of thirty-one.

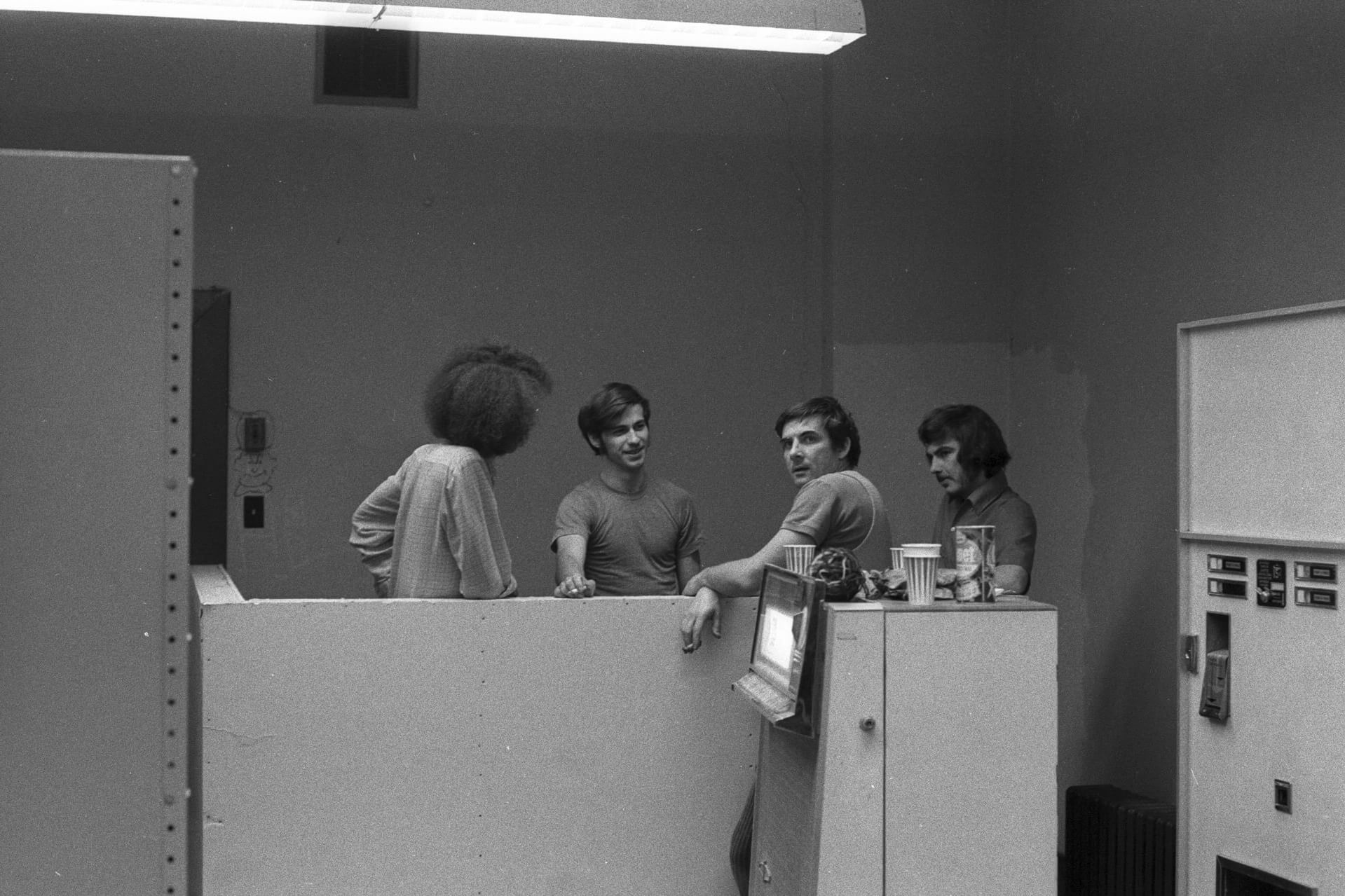

For twenty-three years Kennedy led the art college (renamed the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design [NSCAD] in 1969) through an era that saw such remarkable innovations as an international Visiting Artists Program, a publishing house, the famed NSCAD Lithography Workshop (1969–76), and two exhibition spaces. He hired a team of accomplished artists and educators—Gerald Ferguson (1937–2009), David Askevold (1940–2008), Patrick Kelly (1939–2011), Dennis Young (1928–2021), and Jack Lemon (b.1936), among many others—and gave them the room (and the financial support) to create programs that would prompt one international art magazine to wonder: Was NSCAD “the best art school in North America?”

In Kennedy’s first two years at the art college he oversaw the construction of a six-storey addition to the college’s building that included a space for an art gallery and greatly expanded course offerings. In 1969 the college achieved degree-granting status—the first art college in Canada to do so. In 1973 the school began its graduate program. From 1972 until 1978 Kennedy oversaw NSCAD’s move from the Dalhousie University campus to a downtown block of buildings on the waterfront: Historic Properties. This move not only grew NSCAD’s footprint; it also contributed to saving a large part of Halifax’s historic downtown area that had been slated for demolition. As one board member recalled, “if you like Historic Properties, you should remember that it was the art college that made it possible.”

Kennedy resigned from NSCAD’s presidency in 1990, but he remained a full-time professor until retiring from the art college in 2005 (he continued to teach part-time until 2011). Always an active artist, Kennedy maintained his exhibiting career until his death. His nationally touring retrospective, Garry Neill Kennedy: Work of Four Decades, was organized by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS) and the National Gallery of Canada in 2000. In 2012 the MIT Press (with the AGNS and NSCAD) published Kennedy’s mammoth history, The Last Art College: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968–1978. In 2014 he moved to Vancouver to teach at the University of British Columbia. He died in Vancouver in 2021.

Bernard Riordon (b.1947)

In 1973 Bernard Riordon graduated from Saint Mary’s University with a Master of Arts in Canadian history. During his two years of studies, he worked at the university’s art gallery, assisting its then director, Robert Dietz. Dietz recommended Riordon to the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts (NSMFA) for the position of curator at the Centennial Art Gallery, which had been established by the NSMFA in 1967 and was located at the time in a former powder magazine in the Halifax Citadel. Successfully appointed to the role in 1973, Riordon never looked back.

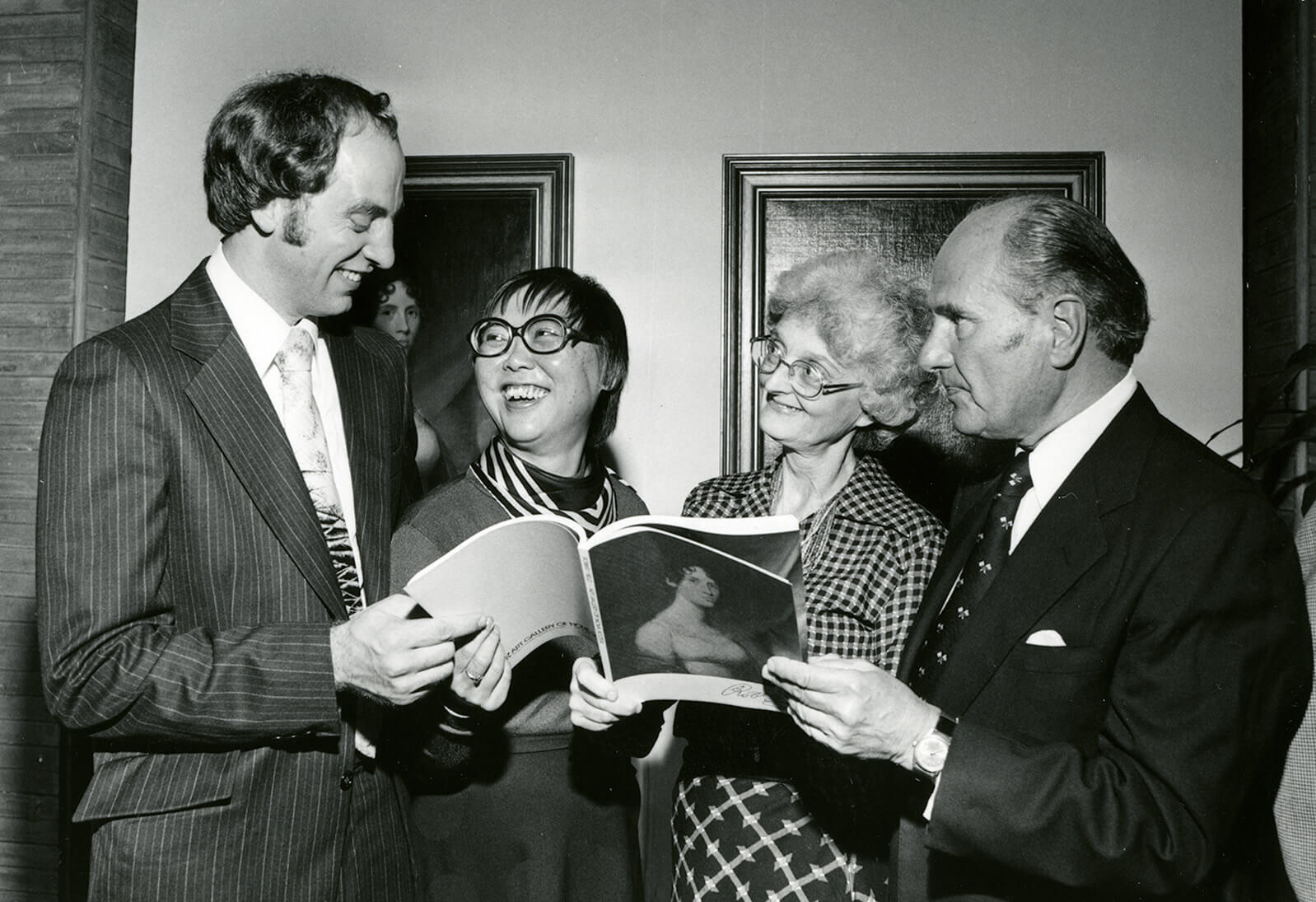

In 1975 the NSMFA moved to the newly vacated premises of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design on Coburg Road, and later that year, after the passage of an act of the Provincial Legislature, the NSMFA was reborn as the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS), with Riordon as its director and curator. In 1976 Riordon organized the AGNS’s first touring exhibition, Folk Art of Nova Scotia, which travelled across the country in 1977 and 1978, including to the National Gallery of Canada. The exhibition introduced Canadian audiences to Nova Scotia folk artists such as Collins Eisenhauer (1898–1979), Ralph Boutilier (1906–1989), and, most importantly for Riordon’s future career, Joe Norris (1924–1996) and Maud Lewis (1901–1970).

In the ensuing decades Riordon would oversee the creation of the AGNS’s first permanent home, which opened in 1988; the gallery’s expansion, which opened in 1998 (and included a home for the restored Maud Lewis House); and the official opening of the AGNS Western Branch in Yarmouth in 2006. He curated nationally touring exhibitions of the works of Maud Lewis and Joe Norris, and he wrote a book on Norris that was published in 2000. Under his leadership folk art was arguably the main focus of the gallery, and he was instrumental in bringing the work of Maud Lewis to wider audiences.

Riordon oversaw the growth of the AGNS from its roots as a small, mostly volunteer-led collecting society that had tried, and failed, to create a permanent gallery for almost seventy years. Under his leadership the gallery grew from a staff of one in 1973 into a professional art museum with a staff of forty-plus twenty years later.

Riordon was born in Bathurst, New Brunswick, and he still maintains a home and farm in nearby Pokeshaw. He is married to Lillian Riordon, and they have four children. Riordon retired from the AGNS in 2002, and he became director and CEO of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton later that year. Riordon was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2002, and he received an honorary degree from Saint Mary’s University in 2009. He retired from the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in 2013 and was named director emeritus.

David Woods (b.1959)

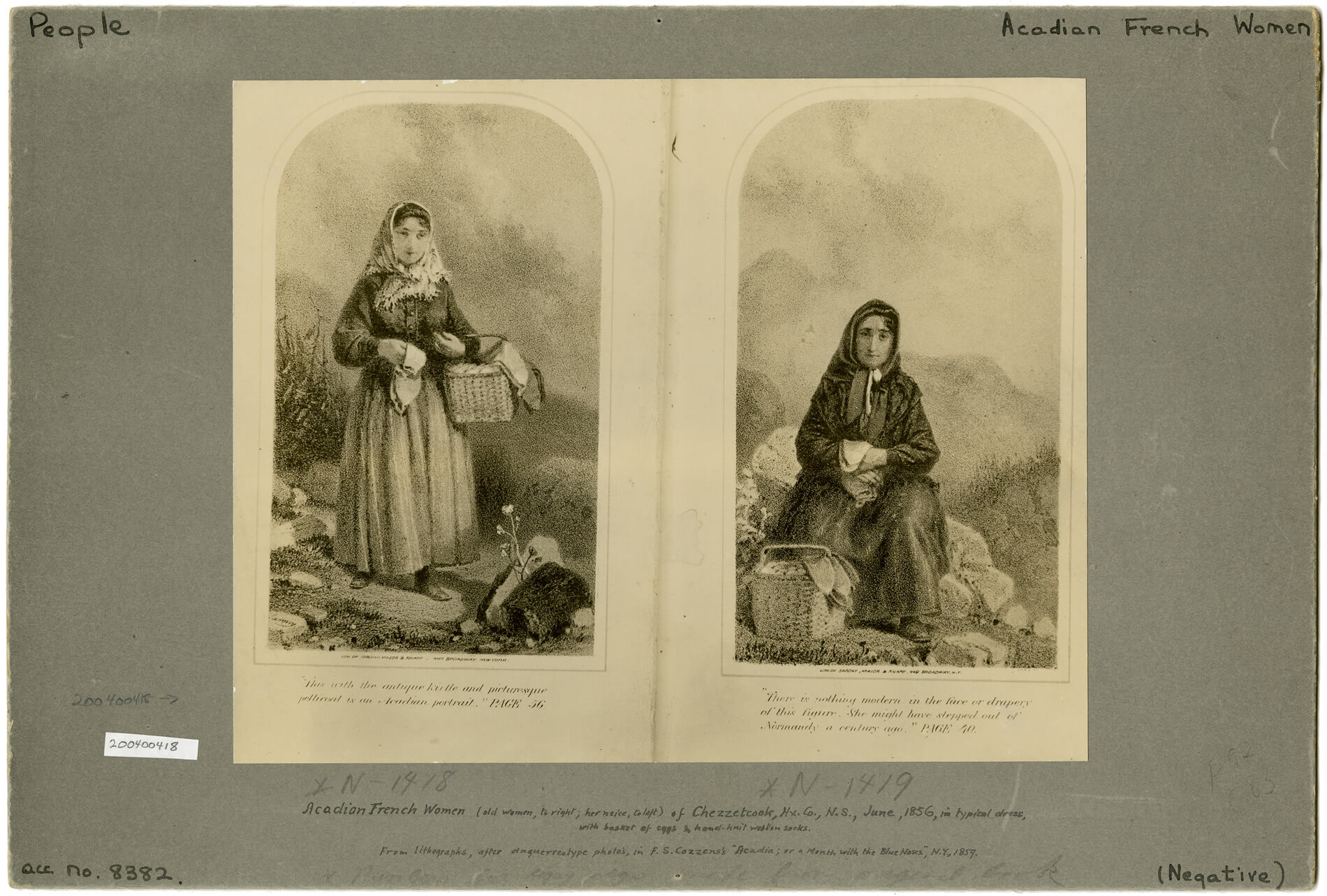

In 1998 the groundbreaking exhibition In This Place: Black Art in Nova Scotia, a survey exhibition of over a century of African Nova Scotian art, was held at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design’s (NSCAD) Anna Leonowens Gallery. The first exhibition of its kind in Nova Scotia, it was co-curated by David Woods, a vital figure in bringing the art history of African Nova Scotians to larger public attention.

In This Place featured works from 1880 to 1998. As a feature article by Kelsey Adams in Canadian Art magazine recently noted, “In a way, Woods worked like an archivist, documenting these pieces before they could be lost to memory.” Originally envisioned to be a small exhibition featuring Black NSCAD graduates, the project received so few submissions that Woods was brought on to help recruit more artists from the Black community. Under his direction, the small show blossomed into an exhibition of more than one hundred works by forty-six artists that also toured to other Nova Scotia communities (Shelburne, Sydney, and Stellarton). Contemporary artists, such as Justin Augustine, Jim Shirley (an expatriate American artist who had the first solo show by a Black artist in Halifax at MSVU Art Gallery in 1977), and Crystal Clements, were shown with artists from previous generations, such as Audrey Dear Hesson (b.1929), a Halifax craft artist who in 1951 became the first Black artist to graduate from the Nova Scotia College of Art.

Born in Trinidad and Tobago, Woods emigrated to Canada in 1972, when his family settled in Dartmouth, now part of the Halifax Regional Municipality. In 1981 Woods took a temporary job with the Black United Front (BUF), in which he was asked to design a program aimed at educating Black children raised in white foster families about their cultural heritage. Woods instead made the program available to all Black students in Halifax, through newly created high school youth groups. When the program was discontinued by BUF a year later, Woods established the Cultural Awareness Youth Group (CAYG), an independent youth leadership development and cultural education agency to continue his popular programs. Woods ran CAYG until 1989.

A prolific artist, writer, curator, and organizer, Woods has been a tireless advocate for Black art in Nova Scotia for decades. In 1984, through CAYG, he organized the first public programs for Black History Month in the province, and in 1992 he was the organizing founder of the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia. In 2006 Woods was appointed associate curator of African Canadian art at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia under the tenure of director Jeffrey Spalding (1951–2019). Woods made an immediate impact by organizing two exhibitions of Black contemporary art (Visions in African Nova Scotian Art and The Soul Speaks) and spearheading the acquisition of a painting by Edward Mitchell Bannister (1828–1901), a New Brunswick-born American painter who was one of the few African American artists of the nineteenth century to achieve significant recognition (Bannister was the first artist of African descent to win a major art prize in the U.S., when he received the first place bronze medal for Under The Oaks at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876). Woods and Spalding also brought the important exhibition Mary Lee Bendolph, Gee’s Bend Quilts, and Beyond, co-organized by the Austin Museum of Art and Tinwood Alliance, Atlanta, to Halifax, the touring exhibition’s only Canadian venue. An artist himself, Woods exhibits his own artwork (paintings, installations, and quilts) in galleries across Nova Scotia and Canada.

Woods continues to curate and organize. An expanded version of his 2012 exhibition of African Nova Scotian quilts, The Secret Codes, was organized for a national tour of Canada from 2022 to 2025. At the time of writing, Woods is also developing an exhibition of the work of Edward Mitchell Bannister with the Owens Art Gallery in Sackville, New Brunswick, planned for the spring of 2025.

Dianne O’Neill (b.1944)

For more than forty years no one has written more about the art history of Nova Scotia and its capital city than Dianne O’Neill. She has taught art history, managed collections, and installed exhibitions, but it is as a curator and art historian that she has primarily made her mark on Halifax’s art history. Like her predecessors Harry Piers (1870–1940) and Donald Cameron (D.C.) Mackay (1906–1979), she is a prominent scholar in the art history of Halifax. Where she differs, however, is in her insistence on documenting the stories of individuals and groups who have been mostly left out of the historical narrative, particularly women and Indigenous artists.

Mora Dianne Guthrie was born in Port Elgin, Ontario, in 1944, and earned a PhD in theatre history and art history from Louisiana State University in 1976. She married Patrick Bernard O’Neill in 1967 and moved to Halifax when her husband took up a teaching appointment at Mount Saint Vincent University.

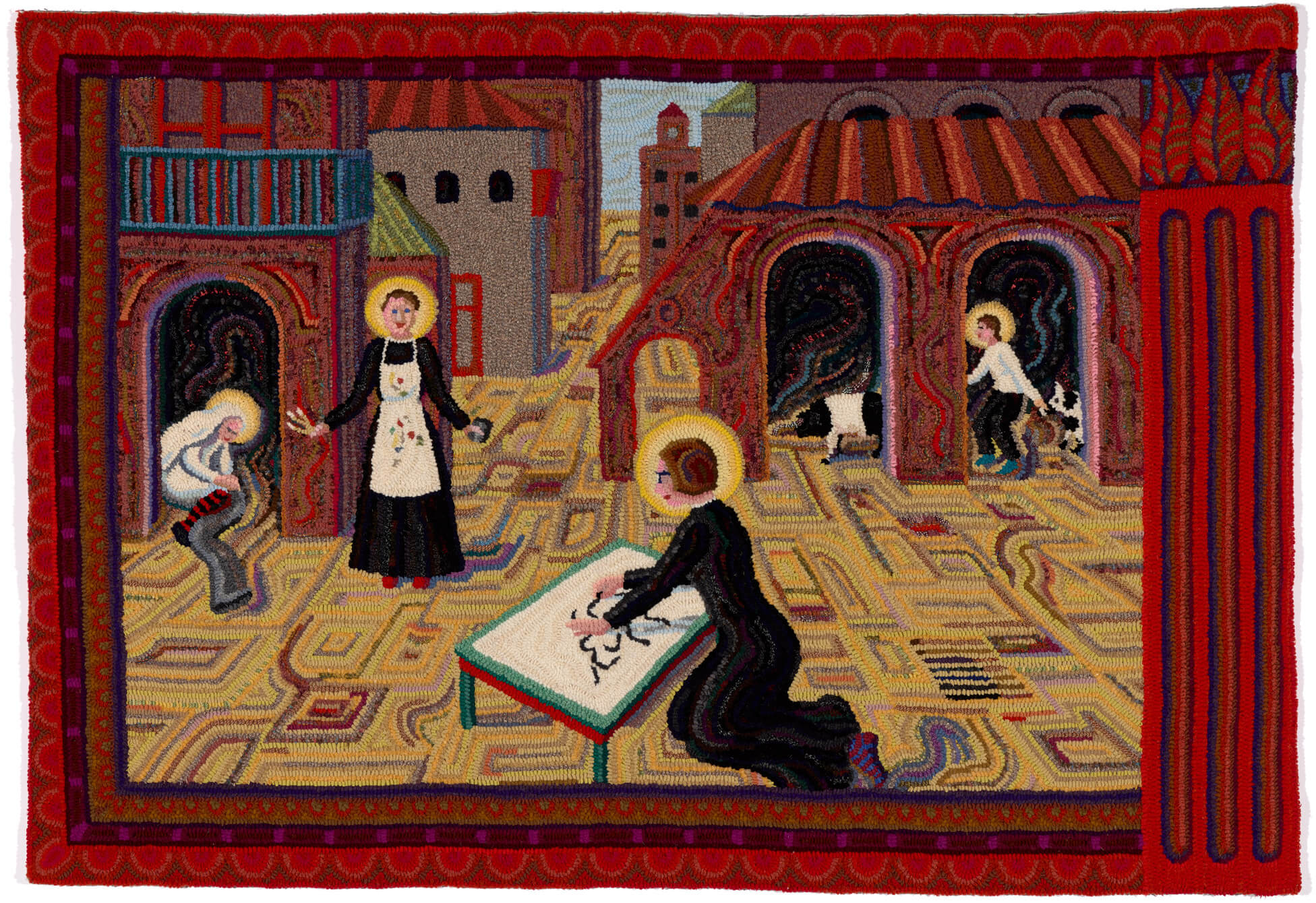

From 1978 until 2019 O’Neill worked in various roles at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS): as volunteer, guest curator, research officer, editor, and, most importantly, as adjunct curator and then with the title of Associate Curator, Historical Prints and Drawings. Over her career at the AGNS she curated or co-curated more than seventy exhibitions for the gallery, including Pe’l A’tukwey: Let Me… Tell a Story: Recent Work by Mi’kmaq and Maliseet Artists, 1993, the first museum exhibition of Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqey contemporary art ever mounted; full-career retrospectives of Forshaw Day (1831–1903), Henry M. Rosenberg (1858–1947), Frances Jones (Bannerman) (1855–1944), and Margaret Campbell Macpherson (1860–1931); and historical exhibitions such as At the Great Harbour: 250 Years on the Halifax Waterfront, 1999, and Choosing Their Own Path: Canadian Women Impressionists, 2001–02. O’Neill also curated contemporary art projects, including a 1992 exhibition by Alan Syliboy (b.1952) (his first exhibition in a public art gallery) and the touring exhibition Art Nuns: Recent Work by Nancy Edell, 1991–93.

O’Neill’s focus on Halifax’s and Nova Scotia’s art history has led to important publication projects such as The Nova Scotia Society of Artists: Exhibitions and Members, 1922–1972 (1997) and Paintings of Nova Scotia: From the Collection of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (2004), the latter of which won the 2005 award for Best Atlantic Published Book at the Atlantic Book Awards. Since retiring from the AGNS in 2019 she has remained active as a researcher, writer, and editor, and she is currently working on revising for publication Mackay’s Portraits of a Province: 1605–1945.

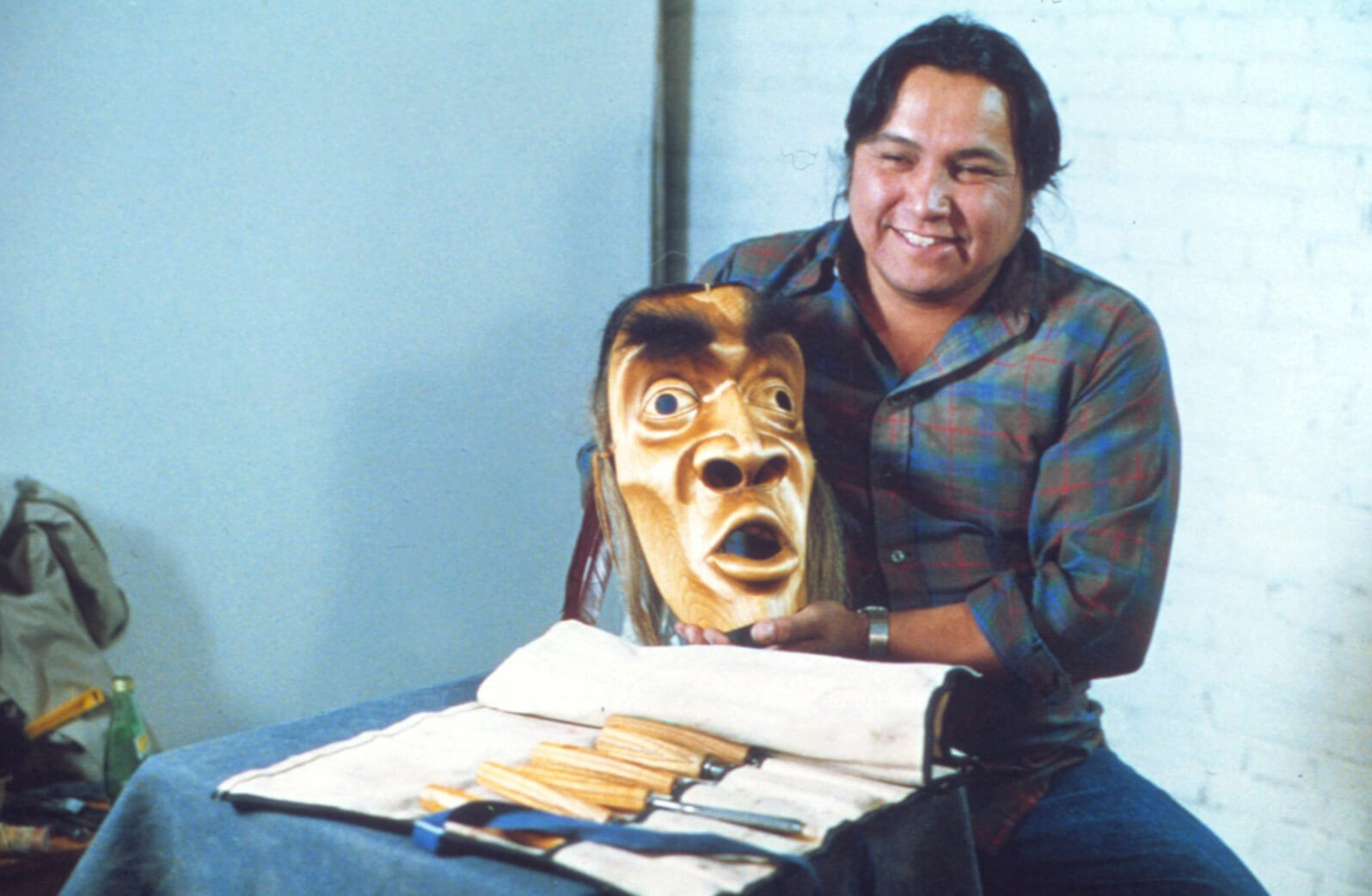

Catherine Anne Martin (b.1958)

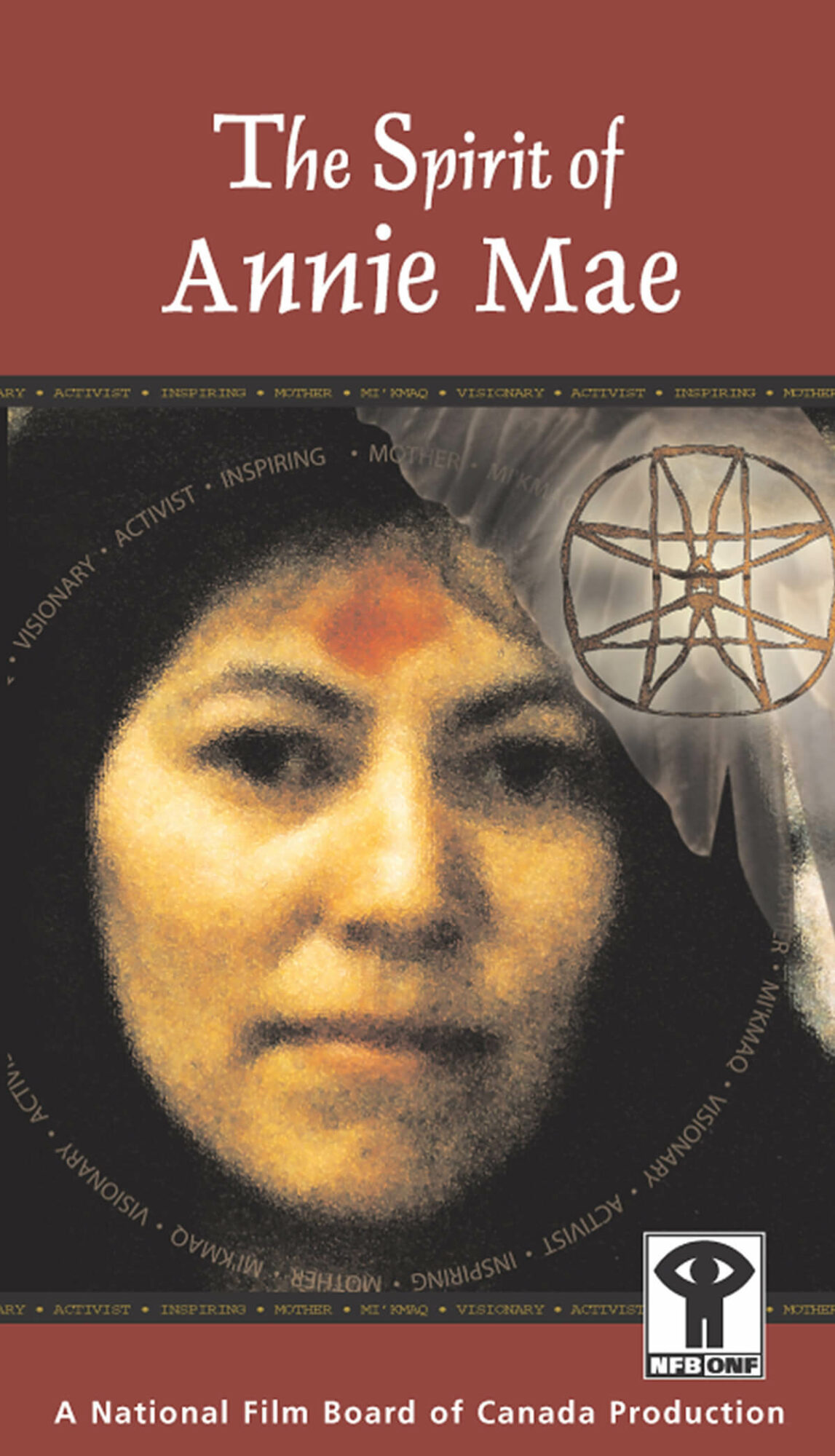

The first Mi’kmaw film director from the Atlantic region, Catherine Anne Martin has been an artist, activist, and advocate throughout her career. The director of numerous documentary and feature films, she has also produced programs for television and educational use. Her first film project was Minqon Minqon, a 1990 profile of Wolastoqi artist Shirley Bear (1936–2022). In 1991 she co-directed Kwa’nu’te’: Micmac and Maliseet Artists with Kimberlee McTaggart for the National Film Board of Canada. The film profiles eight artists (Ned Bear, Shirley Bear, Lance Belanger, Peter Clair, Mary Louise Martin, Leonard Paul, Luke Simon, and Alan Syliboy) and won multiple awards, including an Award for Excellence at the 1991 Atlantic Film Festival. Her 2002 documentary The Spirit of Annie Mae tells the story of the three-decades-long effort to solve the mystery of the murder of Indigenous activist Annie Mae Pictou Aquash. “I was inspired at a young age by Annie Mae’s commitment to make the world a better place for our Indigenous people, especially the [Mi’kmaw],” she says. “She believed in the power of education, the rights of our people to an education and equality.”

Martin’s career has also led her into leadership positions in education and the arts. She has been chair of the board of the Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry, and has served on the boards of the University of King’s College and Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. She has also been instrumental in helping to develop educational programs for Mi’kmaw and Indigenous women and youth across Atlantic Canada, including at Dalhousie University, St. Francis Xavier University, and Mount Saint Vincent University.

Her artistic efforts, her mentorship, and her activism have been acknowledged through numerous awards, including a WAVE Award from Women in Film and Television Atlantic (2015), the Order of Canada (2017), and a Senate 150 Medal (2019). In 2021 she was awarded Nova Scotia’s highest award for the arts, the Portia White Prize.

Martin is a member of the Millbrook First Nation and lives in Halifax.

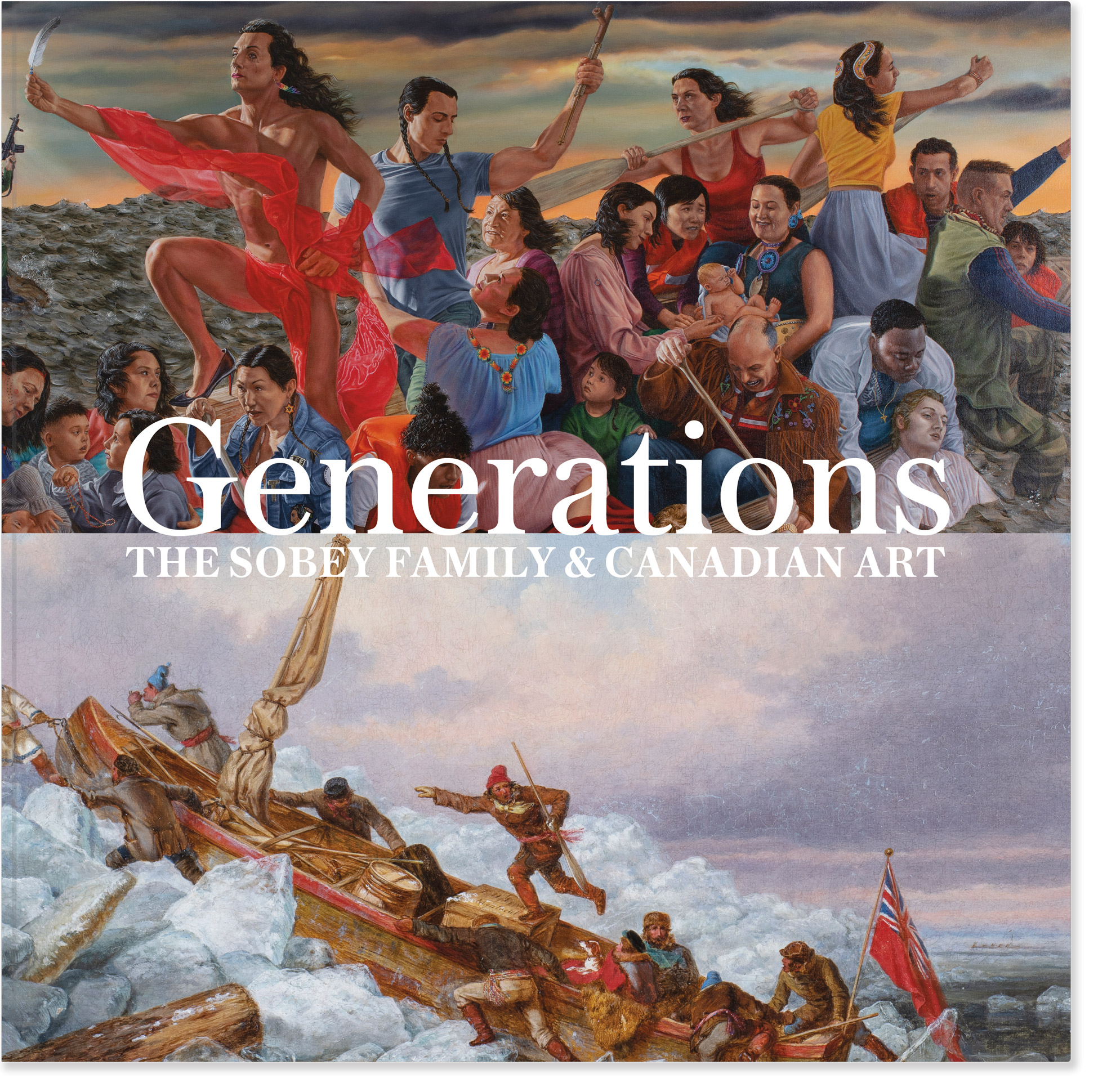

Donald R. Sobey (1934–2021)

Donald R. Sobey never lived in Halifax, but from his home on Nova Scotia’s northern shore he lit the spark that transformed the city’s role in the country’s contemporary art scene and became one of the most influential Canadian art patrons of his generation. Through their many funds and foundations, the Sobey family has supported the arts in this country for decades.

Sobey’s father, grocer Frank Sobey, rose to the top of the Canadian business world from small-town Maritime roots that he never eschewed. To this day the multinational company that he founded remains headquartered in tiny Stellarton, Nova Scotia. Trained from his youth in the family business, Donald R. Sobey had an early and enduring love of Canadian art. He bought his first work, an oil painting by John Lyman (1886–1967), when he was still in his early twenties. He hadn’t grown up surrounded by art. “My mother loved calendars, with big pictures,” he recalled, but “I was the first one who ever bought a painting.” Eventually he helped his father build a family collection of Canadian paintings, as well as growing his own personal collection. Today, the Sobey holdings are among the best collections of Canadian Impressionist and modernist art in private hands.

It was a meeting at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS) in November of 2001 that would cement Sobey’s role as a central builder in Halifax’s art history. By then one of the leading cultural philanthropists in the country, Sobey had already served two terms as chair of the board of the National Gallery of Canada (NGC). He approached Pierre Théberge (1942–2018), then the gallery’s director, with an idea: a prize for Canadian art. Sobey collected historical art, but Théberge suggested another route: “There’s a space no one has built, and that’s for contemporary art,” he told Sobey. Sobey and Théberge brought the notion of such a prize to the AGNS, where I was the curator of contemporary art at the time. I was charged with fleshing out the idea.

Over its more than two decades of existence the Sobey Art Award has become what former NGC director Marc Mayer (b.1956) described as “the pinnacle of contemporary Canadian art.” While the prize is now managed by the NGC, in the thirteen years it was based in Halifax the Sobey Art Award sparked a renaissance for local artists and brought the city into the national and international art conversation in a way that it hadn’t been since the 1970s, during the heyday of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design’s Conceptual era.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements