Greg Curnoe made art from the “stuff” of his everyday life, strongly rejected the idea of moving to “the centre”—Toronto or New York—and was passionately and unapologetically Canadian. Yet from his home in London, Ontario, he was instrumental in fostering and developing a creative milieu that inspired other local artists to produce their own works and put London Regionalism on the map. From his art to his activism, Curnoe often provoked debate.

London Regionalism

Greg Curnoe was, without question, at the centre of the art movement known as London Regionalism. In what he called the “backwater” of London, Ontario, Curnoe’s various studios were the gathering places for a group of artists who supported each other but developed distinct styles of their own. If they occasionally used the word “regionalism” to describe themselves, it was entirely without reference to other movements of the same name around the world. It was Curnoe’s desire to ground his art in authentic, local culture—his daily encounters with his surroundings—rather than in the latest international trend. As he wrote in 1963, “We are not using regionalism as a gimmick but rather as a collective noun to cover what so many painters, writers, and photographers have used—their own environment—something we don’t do in Canada very much.”

Later, after he had named both a magazine and a gallery “Region,” Curnoe explained that he had been unaware of 1930s American Regionalism: “The idea that London’s developing artistic community was an outgrowth of U.S. regionalism was totally inaccurate.” What consolidated the group’s name in public consciousness was the National Gallery of Canada’s 1968 landmark Heart of London exhibition, which toured smaller cities across Canada with works by John Boyle (b. 1941), Jack Chambers (1931–1978), Greg Curnoe, Murray Favro (b. 1940), Bev Kelly (b. 1943), Ron Martin (b. 1943), David Rabinowitch (b. 1943), Royden Rabinowitch (b. 1943), Walter Redinger (1940–2014), Tony Urquhart (b. 1934), and Ed Zelenak (b. 1940).

Before London Regionalism became widely known, however, Curnoe was the instigator for much of the innovative activity that brought the artists together. In February 1962 he organized The Celebration, a Dada-inspired event that caused a sensation in the ultra-conservative city. Toronto artists Michael Snow (b. 1928) and Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), photographer Michel Lambeth (1923–1977), and Dada scholar Michel Sanouillet participated in this first Happening in Canada, which included events such as erecting a huge construction of scrap lumber, doing tableaux vivants, and taking part in a short water battle.

Another of Greg Curnoe’s innovations was the introduction of the artist-run space to London, when he led the founding of the Region Gallery in 1962, so that he and his artist friends could present their own works in uncurated space outside public institutions. He also played leadership roles in the 20/20 Gallery and in the Forest City Gallery. Curnoe explained, “20/20 Gallery was consciously set up as an alternative to the local public art gallery . . . [and] exhibited work that would never have appeared there or in the local commercial galleries.” It was London’s alternative galleries that led the Canada Council for the Arts to fund similar artist-run spaces across Canada in 1967.

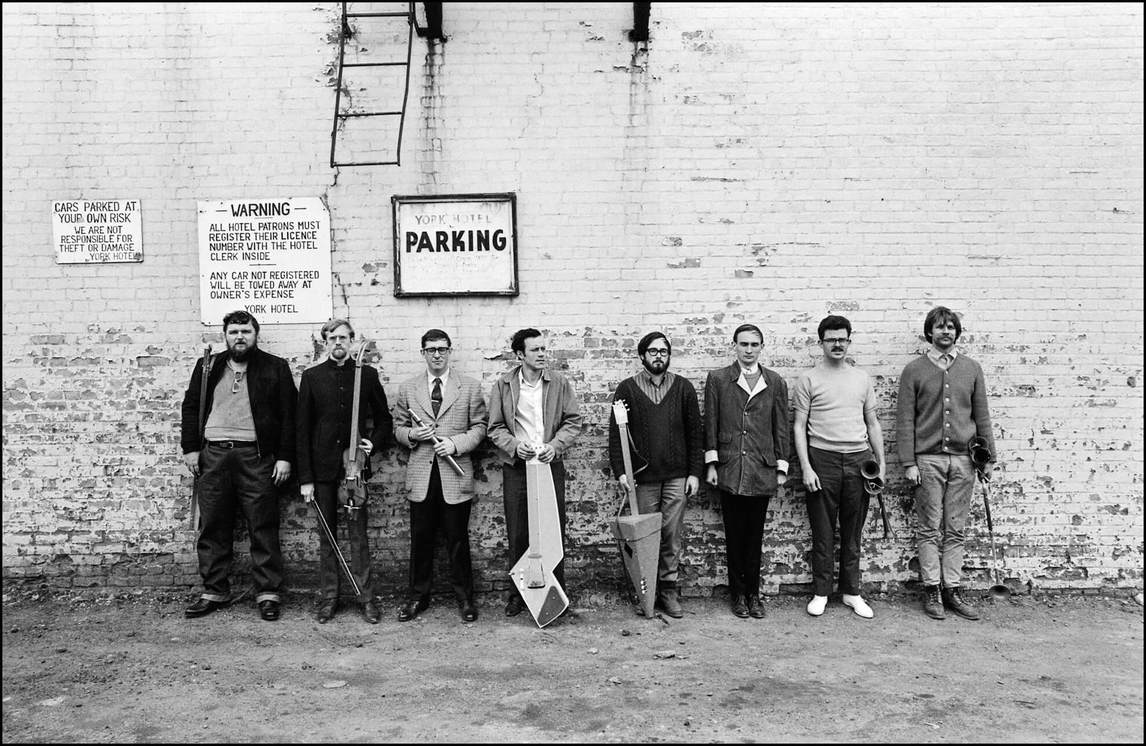

During the 1963 Ontario provincial election, Curnoe founded the Nihilist Party of Canada, a party with no platform and no candidates, and signed up his friends as members. For years, Curnoe and his friends used the Nihilist Party as a pretext for socializing and having fun. Curnoe’s 1965 short film on the history of the Nihilist Party, No Movie, used friends playing kazoos for the soundtrack. The Nihilist Spasm Band followed, using modified and homemade instruments such as kazoos, a megaphone, a gut bucket, a guitar, drums, and a bass. In 1966 the band began regular Monday-night sessions at London’s York Hotel that continue to this day at the Forest City Gallery.

Artists in London, Ontario, were responsible for founding an organization that has had a national impact on artists’ rights. In 1968 Jack Chambers (1931–1978), with fellow artists Kim Ondaatje (b. 1928) and Tony Urquhart, founded Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC) to ensure that artists were paid fairly for the reproduction and exhibition of their work. One of the first members to join, Curnoe was supportive of this initiative and worked locally, provincially, and federally to advocate for the rights of Canadian artists. John Boyle has noted, “Every artist in Canada can thank him whenever he or she is paid an exhibition fee.”

The Search for Self

Canadian artist Alex Colville (1920–2013) once said, “The very decision to become an artist means you are egocentric. The basic assumption is that your life is interesting or that you have something to say about life.” All of Curnoe’s work was a kind of self-portrait, a painted, stamped, assembled, or written autobiography focusing on sometimes obscure daily details, passions, and concerns. His very public presentation of this evolution—the specific record of a man in his region and his personal interests, politics, and self-portraits—are a major contribution to Canadian art.

Greg Curnoe’s interest in the figure began by the age of ten, when he drew cartoons of his family members. Later he painted girls he saw from his studio windows, friends (especially girlfriends), his wife, and his children. His main subject, however, was himself.

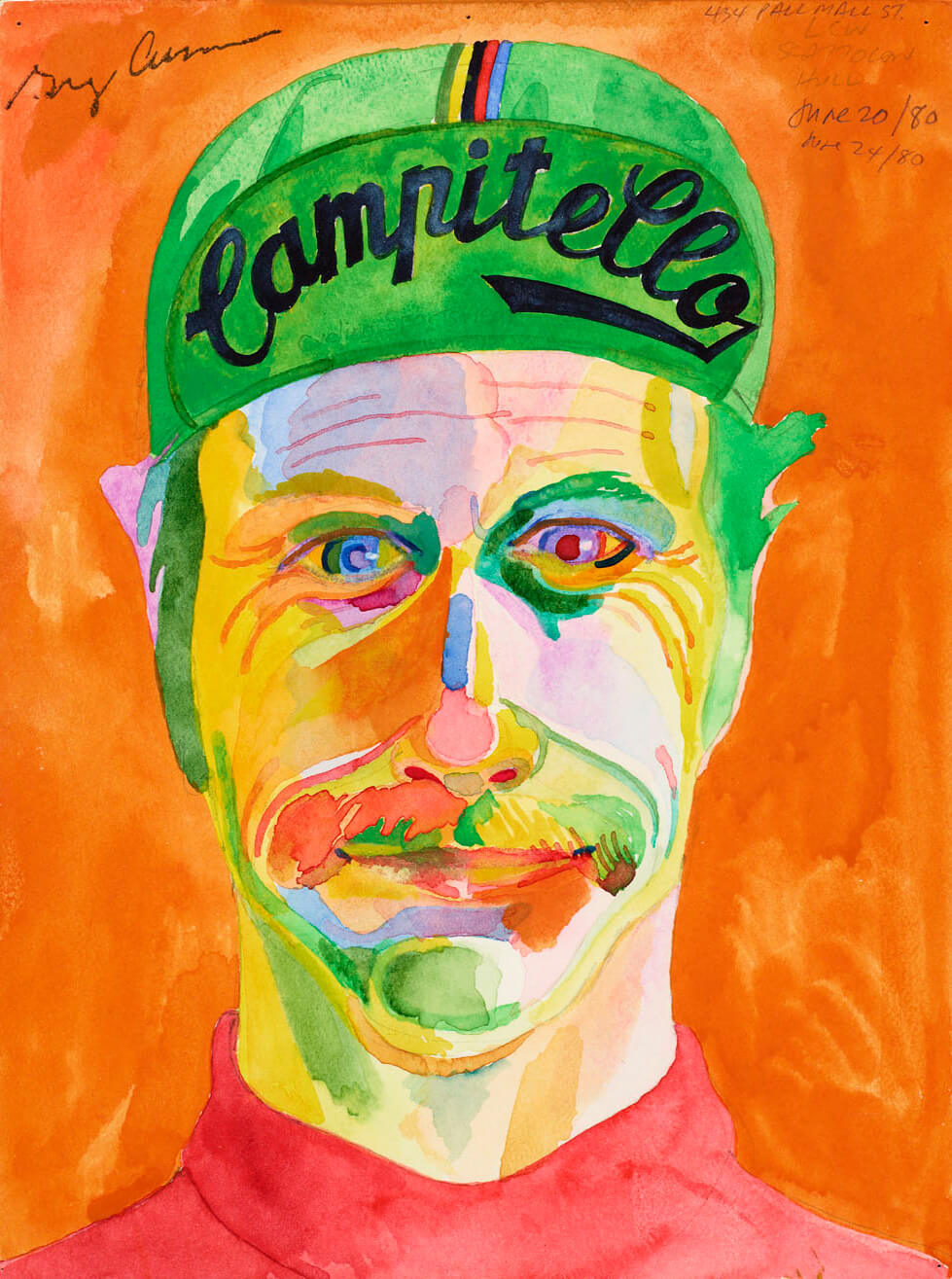

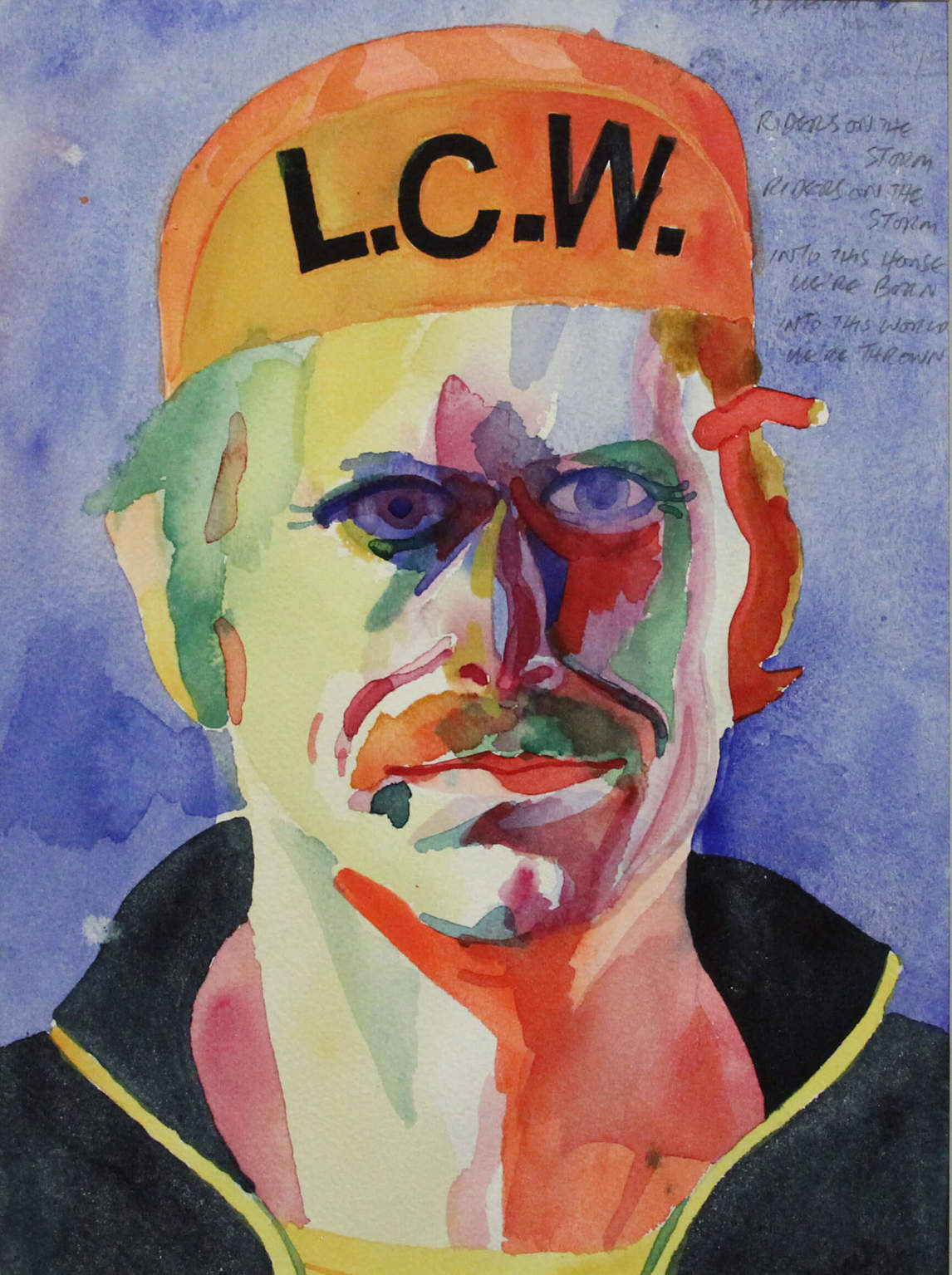

From the 1950s to the day before his death, Curnoe made many self-portraits, no doubt inspired by British Regionalist artist Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), whose work and self-portraits he much admired.

Most often Curnoe painted head-and-shoulder views, especially in several watercolour series he created later in his career, as in twelve from 1980 where he is wearing a cycling cap or helmet. He also did full-length self-portraits, including Myself Walking North in the Tweed Coat, 1963, Middle-Aged Man in LCW Riding Suit, 1983, and the nude self-portrait What’s Good for the Goose Is Good for the Gander, 1983. Unlike most other artists, however, Curnoe painted no self-portraits showing himself with an easel, palette, or brushes to indicate his profession.

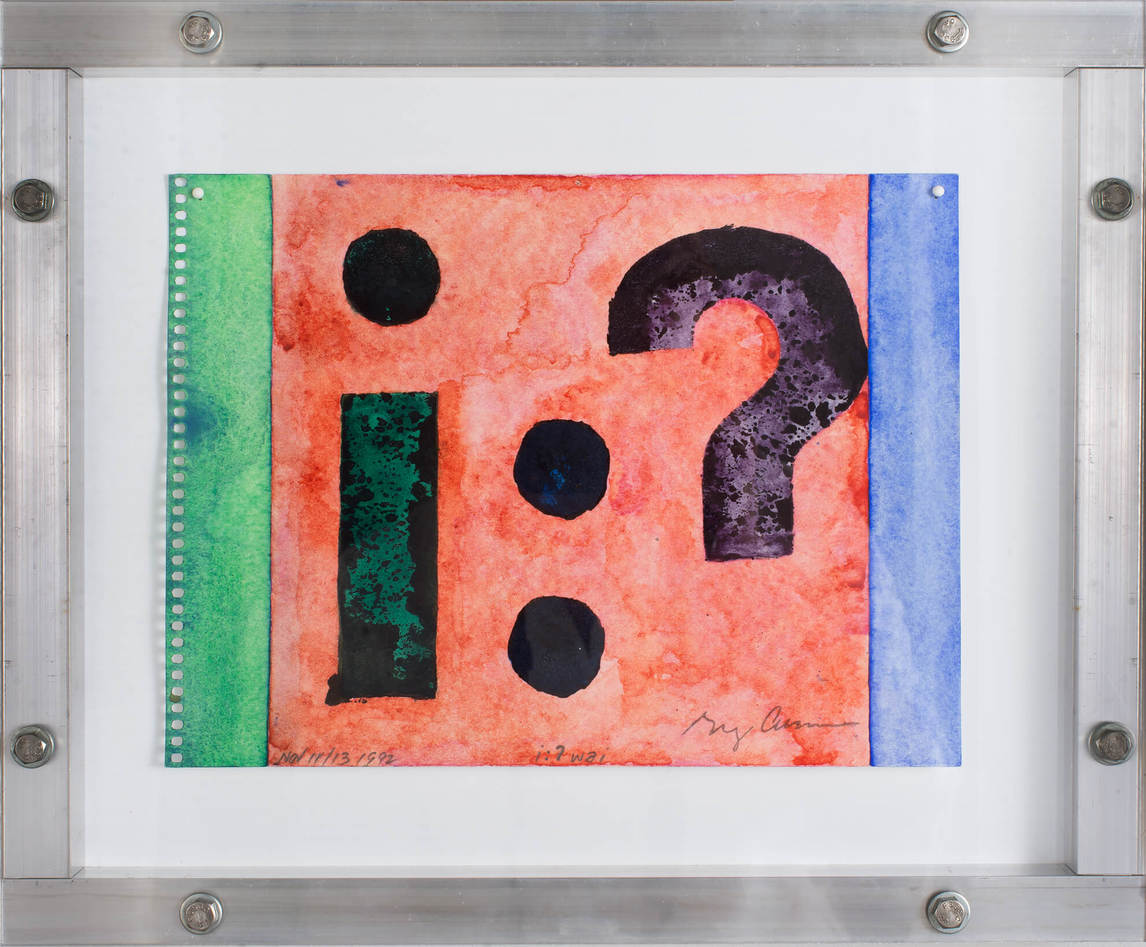

In the last two years of his life, concurrent with his research into indigenous languages, he began a series of more than twenty small, stamped-text self-portraits using the first person in different languages that were important to him—English, French, Ojibwa, Cornish, and Oneida. The work he stamped the night before he was killed was the last in a series that read “i:?” He was still searching for his identity at the end.

Alternative Periodicals

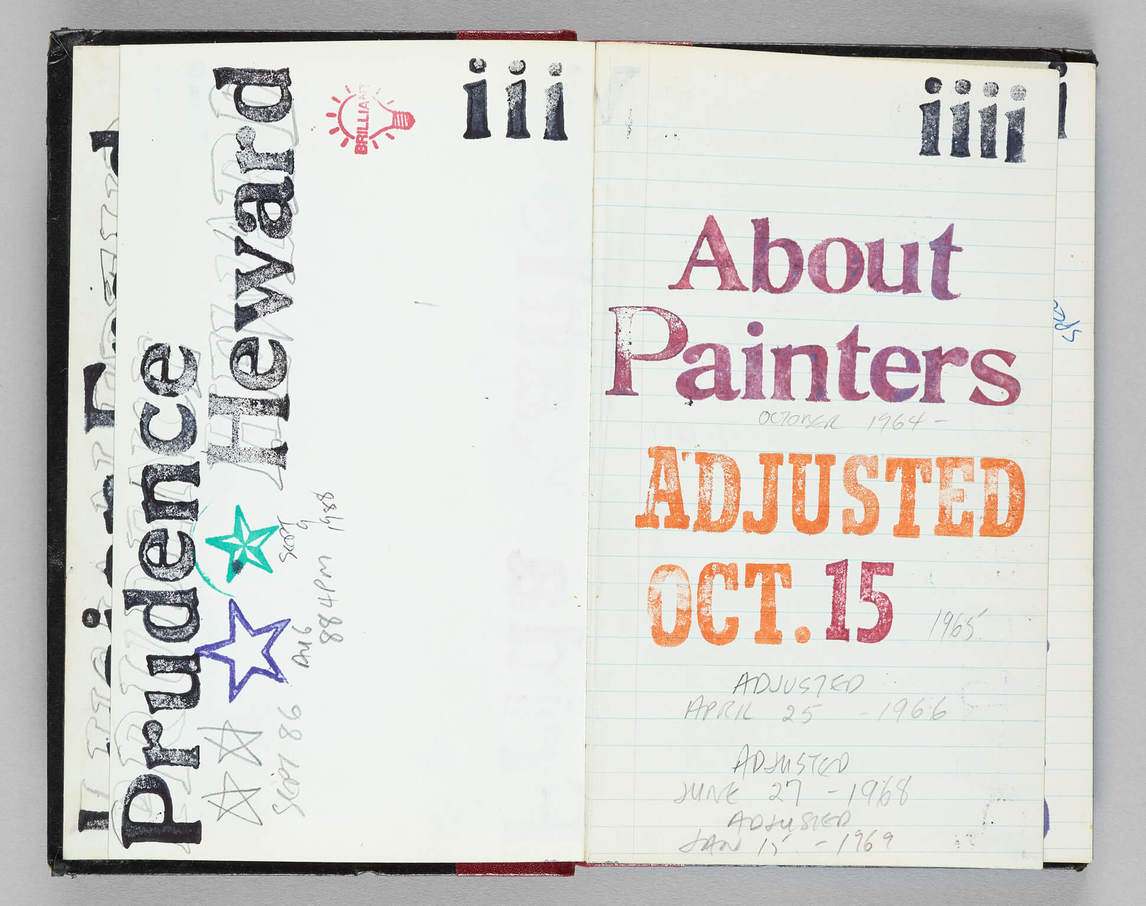

Greg Curnoe was primarily an artist, but words were important both in his works and as an extension of his art practice. He was responsible for inventing and founding four alternative periodicals that provided space for display and discussion outside the mainstream media. The founding editor and publisher of the small magazine Region, Curnoe published ten editions between 1961 and 1990. Concerned about the gradual erosion of Canadian culture, in 1974 Curnoe and Pierre Théberge published one issue of The Review of the Association for the Documentation of Neglected Aspects of Culture in Canada, a catalogue for a documentary exhibition of folk art at the London Public Library and Art Museum (now Museum London).

More than a decade later, Curnoe was awarded a Canada Council for the Arts grant to set up the journal Provincial Essays. Eight volumes devoted to recent Canadian visual culture were published from 1984 to 1989.

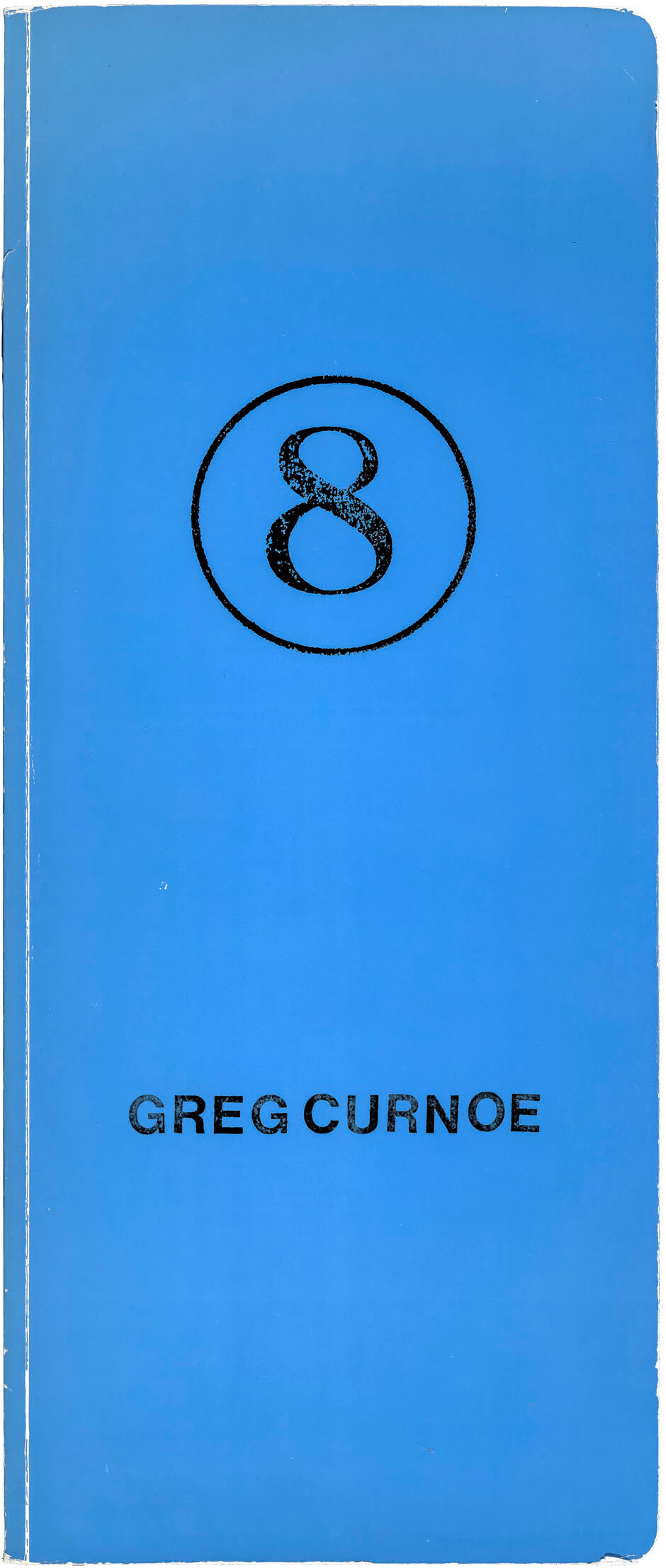

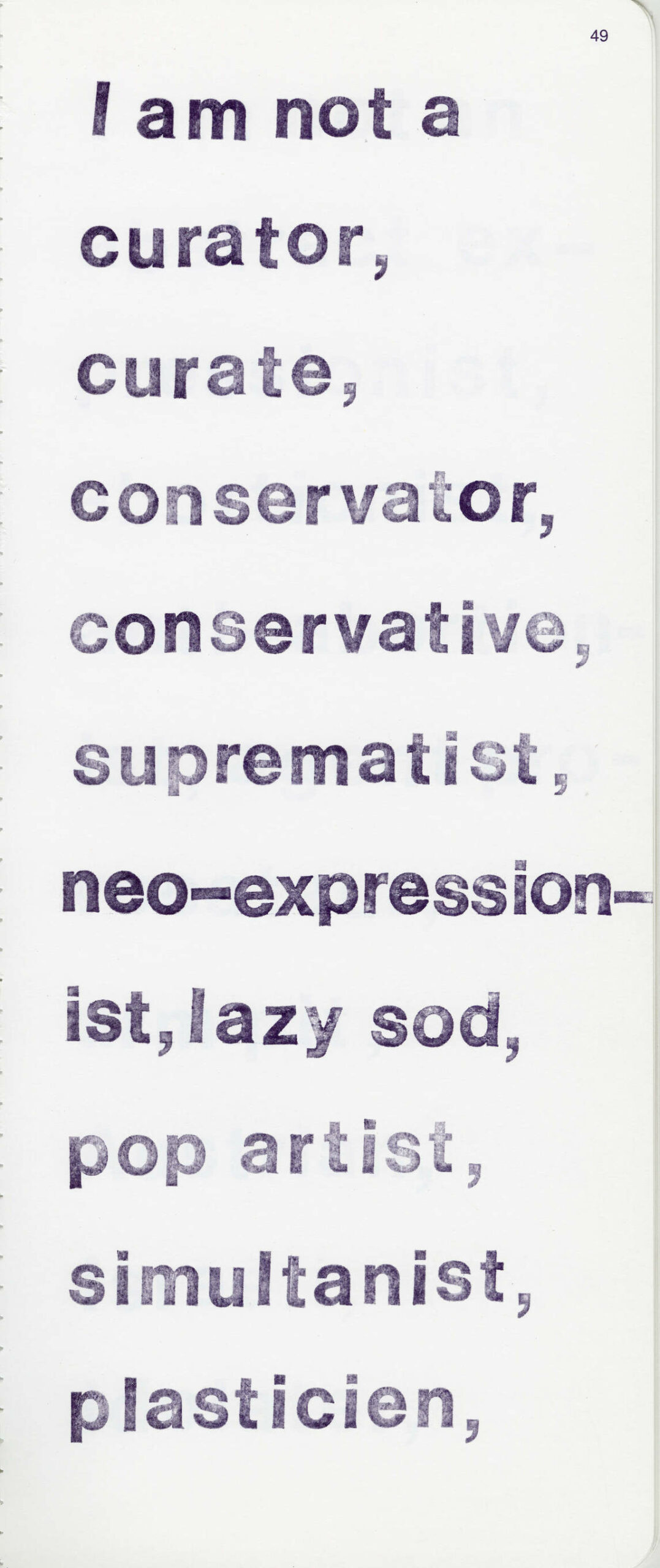

In addition to the periodicals, Greg Curnoe produced one-of-a-kind books, intended as works of art, again with roots in Dada and Conceptual art. Curnoe’s 1962 book works—the seventy-one-page Rain and the seventy-eight-page The Walk—have been acknowledged as the first artist books in Canada. Curnoe made over a dozen such works, perhaps as a more intimate and portable form of working with words and images. Like his paintings, most of these were diaristic, recording his daily thoughts and observations. Perhaps the best known of Curnoe’s books is Blue Book #8, which was published by Art Metropole in 1989. In it Curnoe defined himself negatively, noting 797 times what he was not, ending with “I AM NOT USUALLY PARANOID, GOD’S GIFT TO WOMEN, ILLITERATE, REFUNDABLE, UNDER WARRANTY, COOL, APPALLED, WISE, ALWAYS TRUTHFUL.” This publication is the only one of Curnoe’s artist books printed in a large edition, an inexpensive way of making his art accessible to a wider public.

All of this activity led art historian Barry Lord to describe London, Ontario, as “the most important art centre in Canada and a model for artists working elsewhere” in a 1969 article in the influential magazine Art in America.

Cultural Nationalism, Controversy, and Censorship

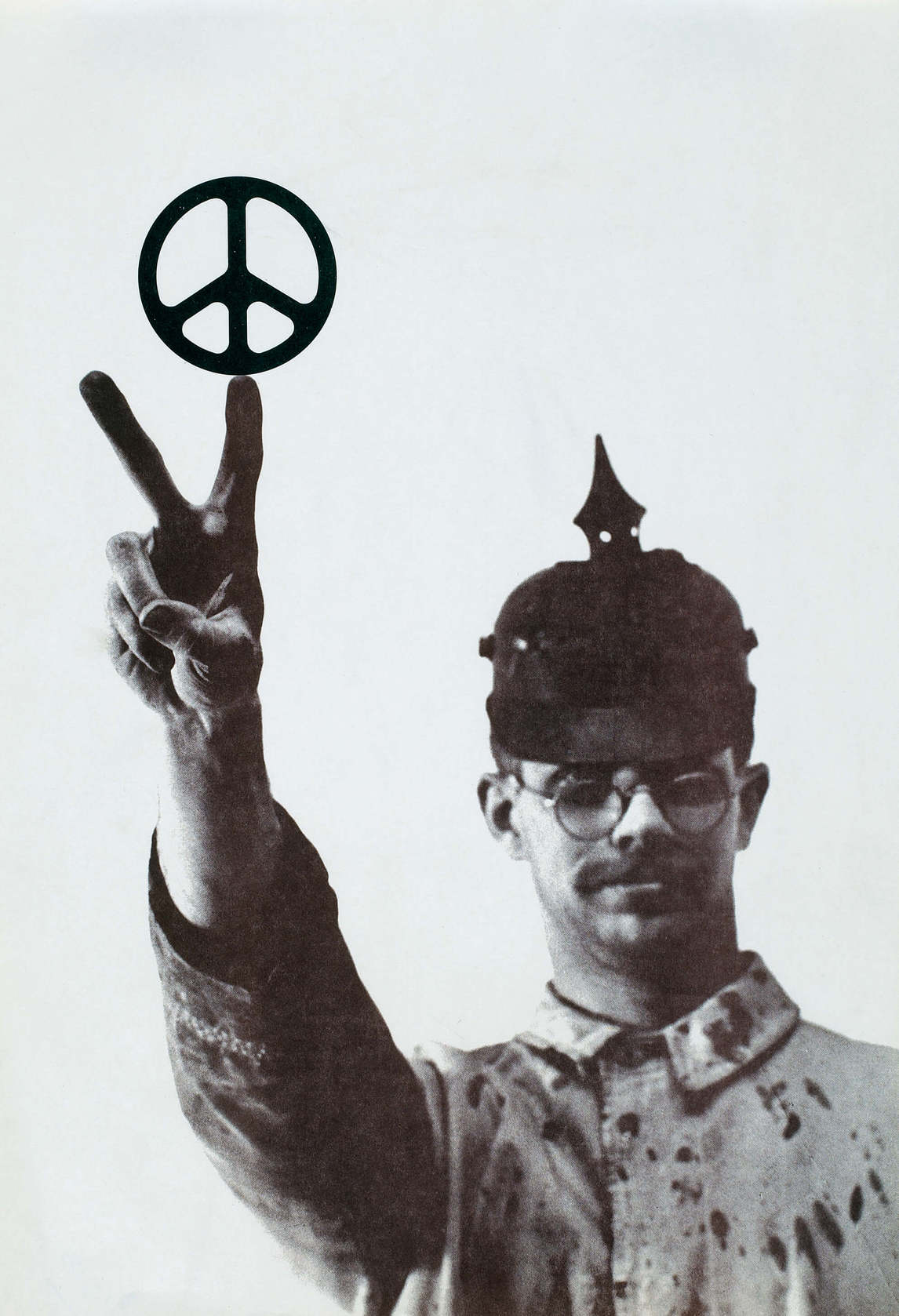

Greg Curnoe began his career at the beginning of a decade of change and turmoil in Canada and the world. Particularly relevant to his oeuvre were the sexual revolution, the Vietnam War, the increasing American influence on life in Canada, and Canadian nationalism. Curnoe was well versed in the debates about American imperialism and Canadian national identity waged in the media and in books by writers George Woodcock, Mel Watkins, George Grant, and Léandre Bergeron. Like other artists such as Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) and John Boyle (b. 1941), Curnoe exhibited his passion for Canada in his paintings, and in articles in journals and letters to the editors of newspapers. He believed that the sought-for Canadian identity resided in regional cultures across the country rather than in a single, unified sense of identity.

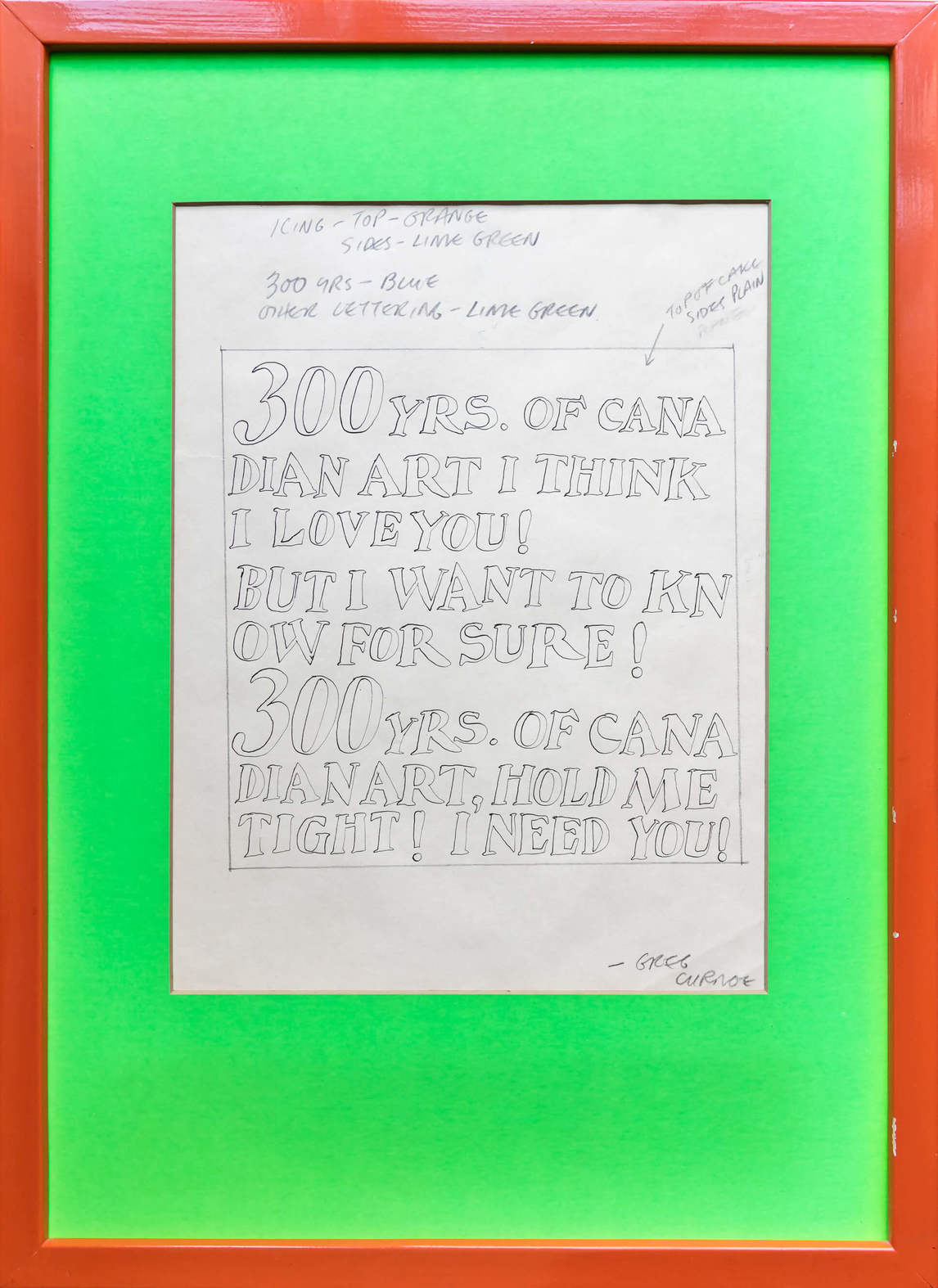

His ambivalent Canadian nationalism is exemplified in his design for Canada’s centennial cake, which was served at the opening of 300 Years of Canadian Art at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 1967. Curnoe’s works often gave visual voice, usually with humour, to what was happening politically in Canada, whether in his portraits of political leaders or in works that posed ironic questions.

For a time, much of this cultural nationalism was directed against the United States. In other words, the reverse side of his Canadian patriotism was “anti-Americanism.” He admitted to being anti-American, but it is important to understand that he was not against individual Americans or aspects of American culture, such as artists, poets, jazz, or comic books. Indeed, it was Curnoe who commissioned an exhibition by American artist Bruce Nauman (b. 1941) at London’s 20/20 Gallery in 1970. Rather, he was concerned with the “cultural imperialism” that he observed with the appointment of Americans in Canadian universities and cultural institutions, and with the corporate takeovers that were happening in London and across the country.

Further, on his first trip to New York in 1965, Curnoe had been shocked by the violent mugging of a friend and subsequently re-evaluated his feelings about the United States. Curnoe refused to exhibit his work there and, true to his principles, later turned down a lucrative opportunity to design a cover for Time magazine. Tellingly, he also excluded a reference to the Time review of the 1968 Heart of London exhibition in all of his files and bibliographic lists.

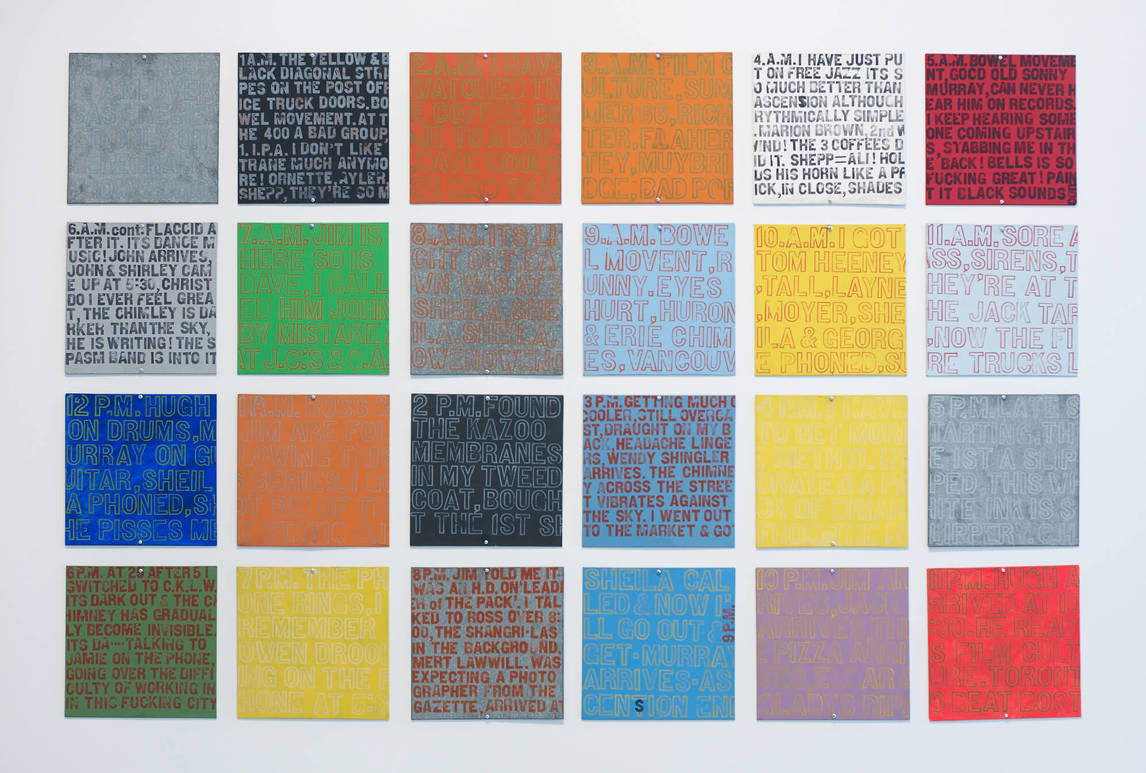

Curnoe’s patriotism overlaid with anti-Americanism led to controversy and censorship. The 1968 removal of his mural from the Montreal International Airport in Dorval, Quebec, because of anti-American statements is still one of the best-known examples of censorship in Canadian art history. Several months later, three panels of 24 Hourly Notes, December 14–15, 1966, were removed from an exhibition in Edinburgh because of “indecent” words. When the same work was exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 1970, a member of Parliament asked the prime minister, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, to have it removed. The work remained on exhibition. Both these issues engendered much national media coverage, including defensive responses from Curnoe.

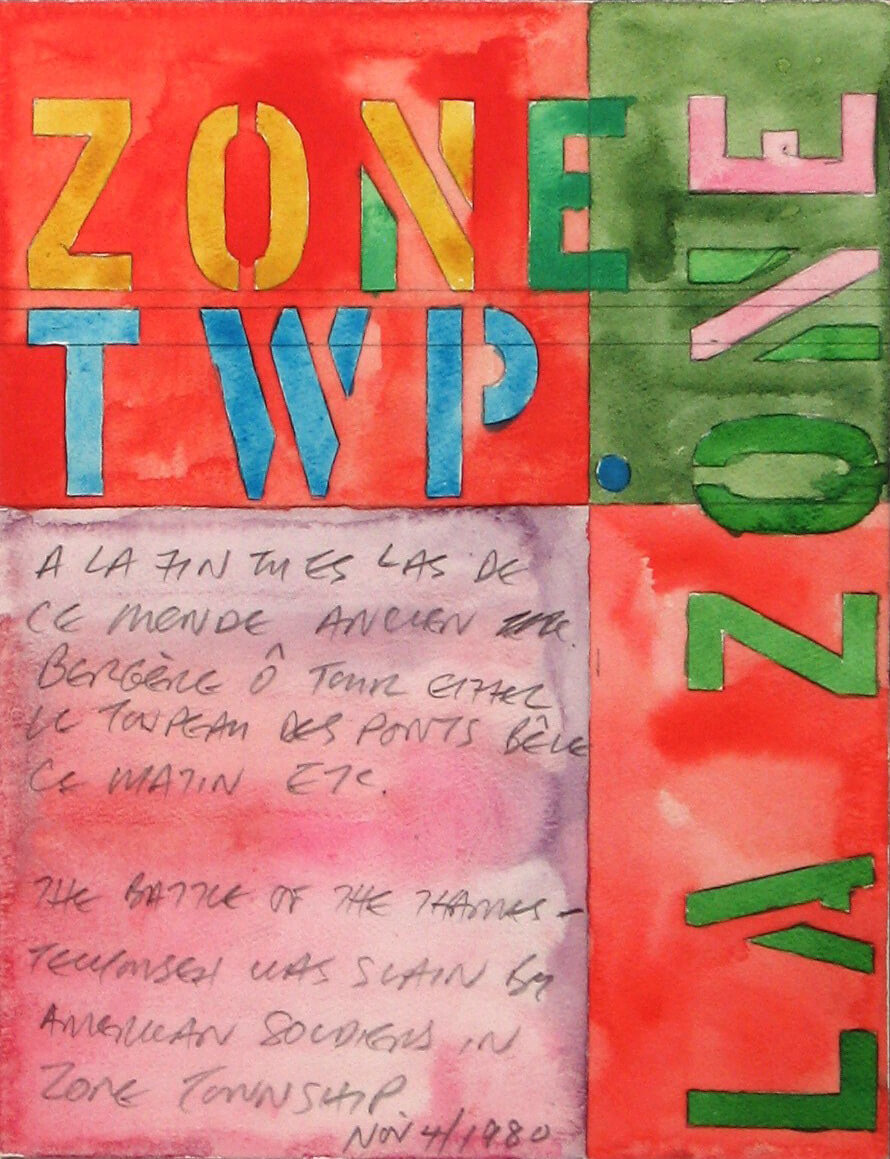

Toward the end of his career, Curnoe began to realize the ultimate irony of the cultural imperialism of his own British ancestors. He had probably became more aware of First Nations history in Canada from his friend and mentor Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979), an expert in indigenous pictographs. While Curnoe was interested in the history of Indigenous Peoples in Canada—there are references in his work to Métis leader Louis Riel and the Shawnee hero Tecumseh, who lost his life close to London in 1813 at the Battle of the Thames—it was not until he began researching the pre-colonial history of the property at 38 Weston Street that a new understanding of Canadian identity began to emerge. As literary and cultural critic Frank Davey noted, “[Curnoe] felt strongly that as a white individual he had benefitted directly from the injustices First Nations people had suffered and that a major part of that benefit was hidden in the Canadian ‘forgetting’ of thousands of years of First Nations social development and inhabiting of the land.”

Influence and Legacy

Greg Curnoe is still held in great esteem by a cross-section of the cultural community. In many ways, he was the heart of art in London. A natural and inclusive leader, he influenced his own generation of artists, and the ones to follow, by his decision to remain in London close to his roots, creating art based on his own environment and experience.

Younger artists were always welcome in his studio. Artist Wyn Geleynse (b. 1947) remembers being there as a high school art student: “Greg showed me that being an artist was a viable thing to do.” He further observed, “He [Curnoe] took the things we take for granted, external things, and gave them legitimacy. You can make work with global relevance by using the everyday. It is how you bring them together that matters.” Royden Rabinowitch (b. 1943), who had exhibited with Curnoe in the 1968 Heart of London exhibition, stressed the importance of the encouragement he had received from Curnoe: “I’ve always thought & still do that the one really immotional [sic] career influence that has affected me & still continues to affect me is my relationship with you. I was always & am continually strengthened by your acceptance of my lovely Barrel staves things & I always think with real feeling of your studio with the photo of my unfinished apple turnover stuck up on your door.”

We will never know the full extent of the influence Curnoe’s talks and teachings had on artists and students across Canada. Artists Jamelie Hassan (b. 1948) and Robert Fones (b. 1949) first encountered him in art classes at H.B. Beal Technical and Commercial High School and eventually became close friends. Hassan wrote: “Our experiences would also entail long hours of debate and argument against ‘everything.’ Connecting people to each other and to ideas and to contemporary culture in Canada was central to maintaining a friendship with Greg Curnoe.” Among the many other artists who came within his orbit were Ron Benner (b. 1949), Andy Patton (b. 1952), Janice Gurney (b. 1949), and Greg Hill (b. 1967), who remembered: “From his example I took comfort in the notion of pride of place and self. His nationalism was surprising to me at the time, but also a little intoxicating.”

More recently, artist Paul Butler (b. 1973) presented The Greg Curnoe Bicycle Project at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Butler’s artistic practice combines art making with community building. Like Curnoe, he has an interest in collage, making lists, and building bikes. On July 23, 2011, Butler rode a replica of Curnoe’s first and favourite Mariposa bicycle through London with Curnoe’s friends and family, visiting important sites in Curnoe’s London. The replica was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario along with items from the Greg Curnoe archives and Butler’s own “Curnoe-style” colour wheel, inscribed with the names of people who had helped with his research.

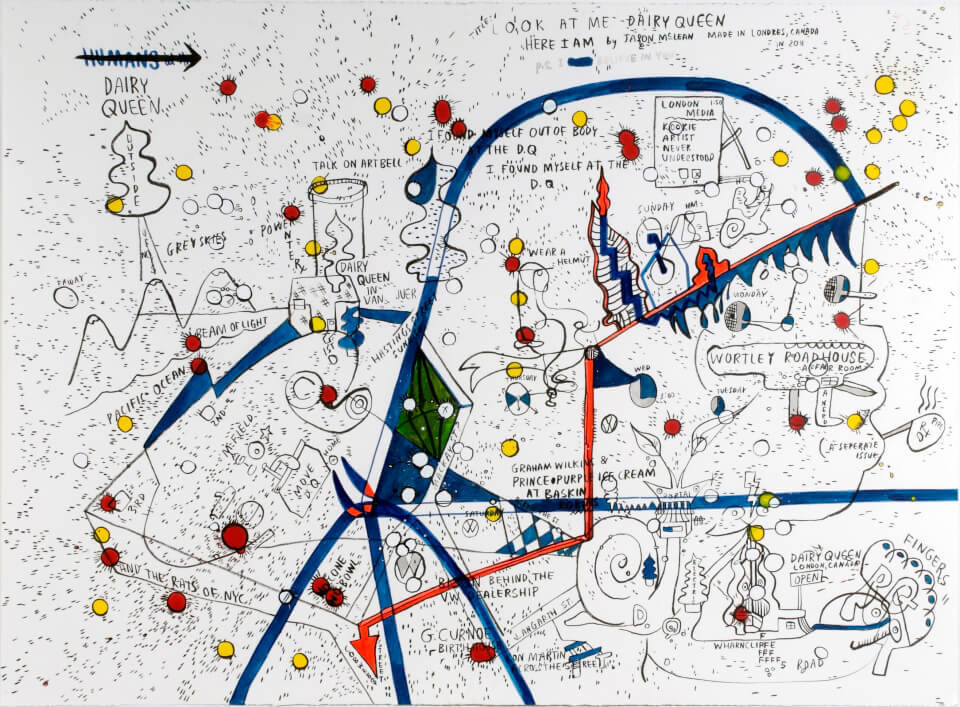

Museum London’s 2013 exhibition L.O. Today featured artists Marc Bell (b. 1971), James Kirkpatrick (b. 1977), Amy Lockhart (b. 1979), Jason McLean (b. 1971), Jamie Q (b. 1980), Peter Thompson (b. 1970), and Billy Bert Young (b. 1983). Their works included text, cartoon-style drawings, found objects, constructions, artists’ books, maps, and ’zines—all showing a debt to Curnoe. However, their collaborative approach, their choices of subject matter and colour, and their use of hand-drawn rather than stamped letters set them apart. For them, Curnoe’s regionalism is a foundation for creating their own idiosyncratic art.

Greg Curnoe’s untimely, ironic death created a hole in the cultural fabric of London and, arguably, Canada that is still not mended. Curnoe, his ideas, his works, and his career have become the “stuff” of myth and legend.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements