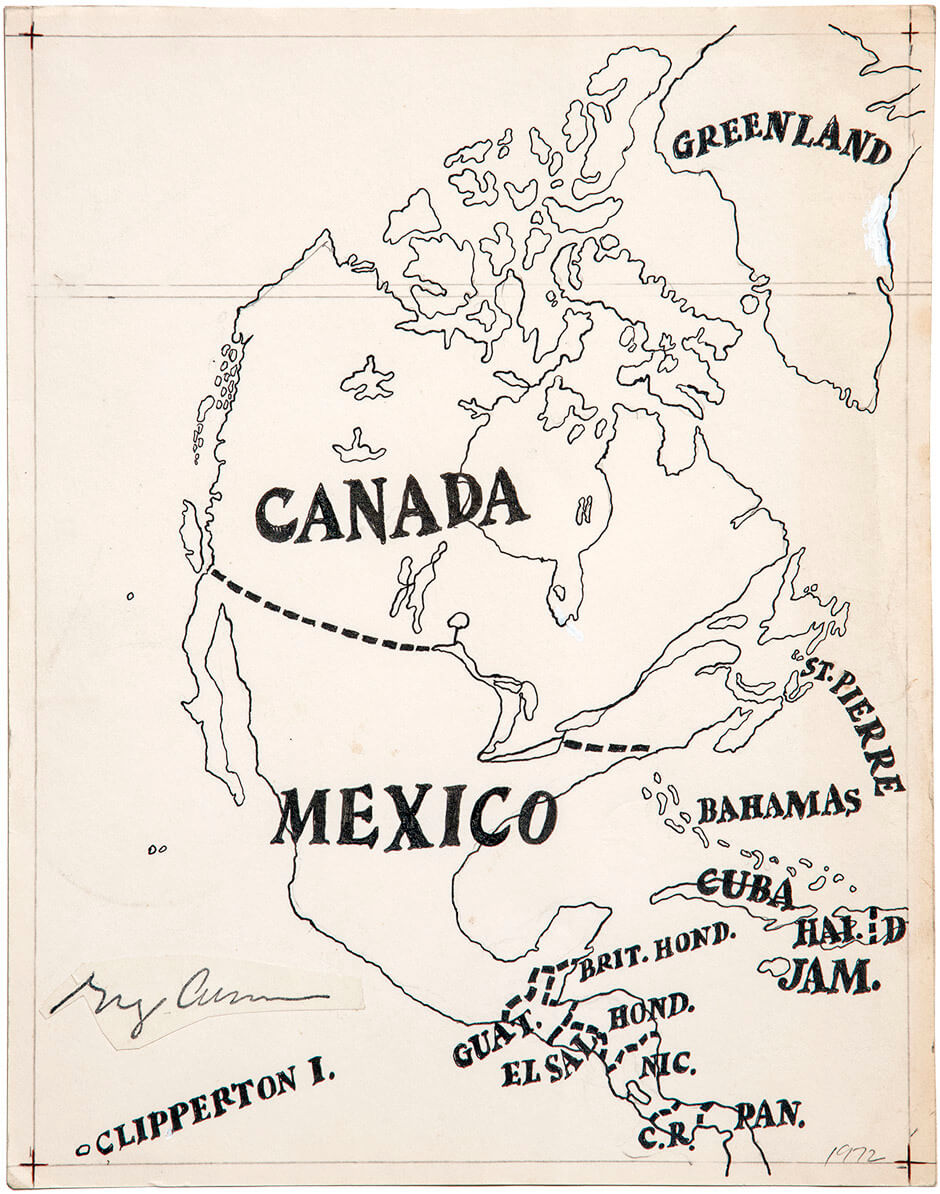

Map of North America 1972

Greg Curnoe, Map of North America, 1972

India ink on paper, 29.5 x 22.2 cm

Dalhousie Art Gallery, Dalhousie University, Halifax

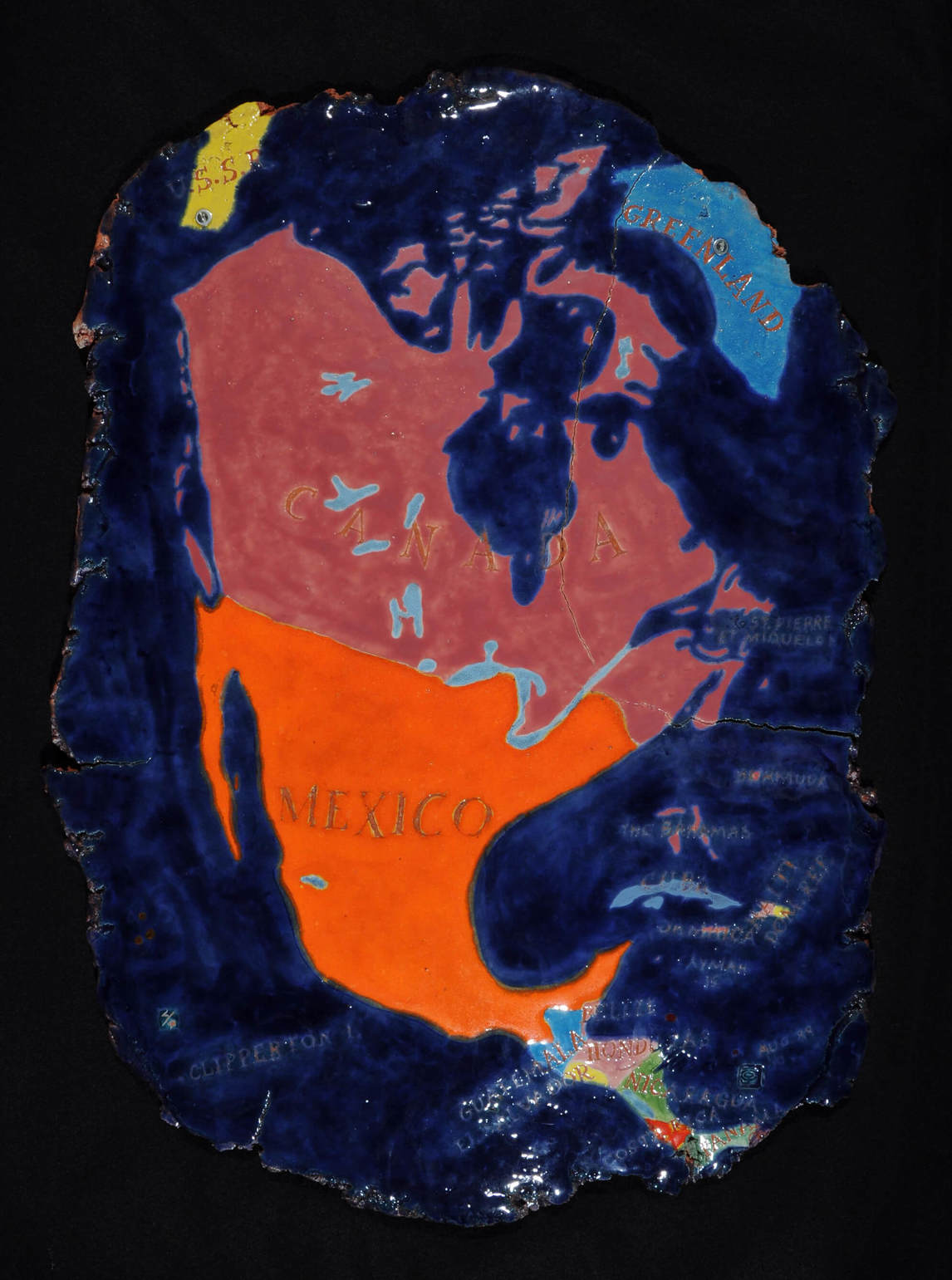

In 1972 Greg Curnoe began the first of several maps of North America, most likely in response to a commission to produce a cover for the January 1973 issue of the Journal of Canadian Fiction. Drawing on an interest in maps and islands informed by his childhood postage-stamp collection and some professional experience with mapping from a summer job in the City of London Surveys Department, he created this ink drawing. It is significant because it expresses Curnoe’s strong anti-Americanism by eliminating the United States entirely, yet naming islands, from Greenland to the obscure Clipperton Island, an uninhabited coral atoll in the Pacific Ocean that is well known to ham radio operators.

Curnoe remembered learning about various historic Canadian border disputes: “The teachers in public school all talked about the Alaska Panhandle . . . and how the United States got that and the Oregon Territory and that bump of Maine that goes up into New Brunswick.” Then, through the 1960s, he was aware of the intense debates raging in Canada about the virtues of nationalism versus continentalism or internationalism. A commission into the arts, letters, and sciences in Canada, led by Vincent Massey, had warned as early as 1951 of the dangers of American influence on media and publishing. Curnoe, living in London, Ontario, less than two hundred kilometres from the U.S. border, witnessed firsthand the influx of American branch plants and university professors to Canada. His personal anti-Americanism had been further reinforced when a friend was violently mugged in New York City in 1965. He made headlines through humour and irony, such as with his 1970 statement, “All Canadian atlases must show Canada’s southern border to be with Mexico. Bridges & tunnels must be built between Canada & Mexico.”

In redrawing the map of North America, Curnoe may well have been aware of the 1929 Surrealist map of the world by an anonymous artist who redrew the continents, eliminating the United States completely. Here he makes his own tongue-in-cheek statement that fits his views about cultural imperialism. Sheila Curnoe recalls her husband coming into their kitchen after he had successfully connected Mexico to the Canadian border: “He was so pleased with himself. He was laughing about it. It was meant to be funny and not to be taken so seriously.” Although Curnoe made other versions of this map, this is the one that has been most exhibited, especially as an example of Conceptual art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements