Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) was the driving force behind a regionalist sensibility that, beginning in the 1960s, made London, Ontario, an important centre for artistic production in Canada. While his oeuvre chronicled his own daily experience in a variety of media, it was grounded in twentieth-century art movements, especially Dada, with its emphasis on nihilism and anarchism, Canadian politics, and popular culture. He is remembered for brightly coloured works that often incorporate text to support his strong Canadian patriotism, sometimes expressed as anti-Americanism, as well as his activism in support of Canadian artists.

Early Years

Gregory Richard Curnoe was born on November 19, 1936, at Victoria Hospital in London, Ontario. He grew up with his parents, Nellie Olive (née Porter) and Gordon Charles Curnoe; his brother, Glen (born 1939); and his sister, Lynda (born 1943), in a house built for the family by his grandfather. For most of his life, Curnoe lived within five kilometres of this home in Southwestern Ontario, a peninsula surrounded by water and the United States. American culture was accessible and pervasive, but the city itself was very British in its geographic names, its architectural style, and its conservatism.

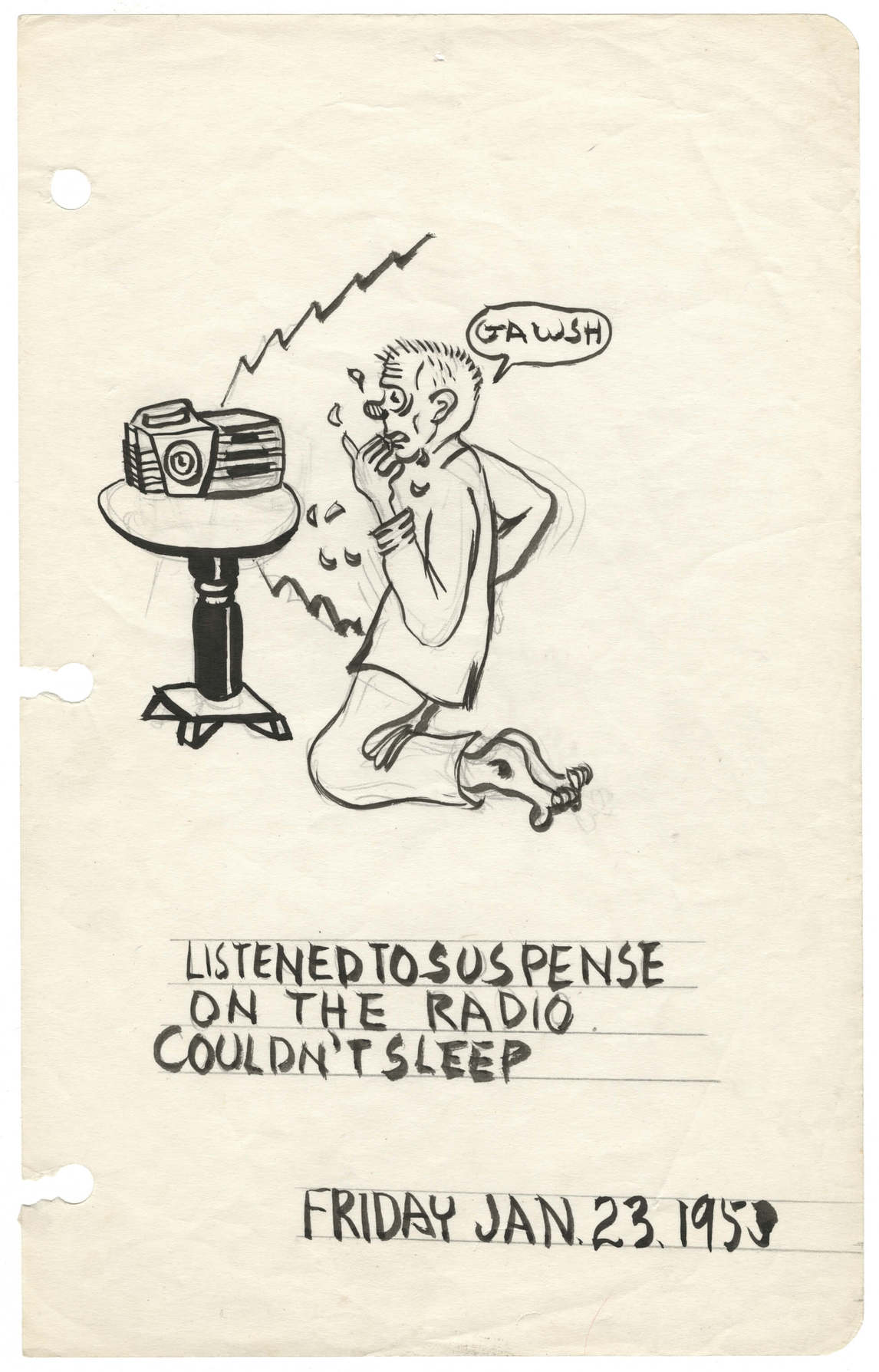

Curnoe’s interests and talents revealed themselves early in life. Just after his tenth birthday, a Christmas gift from his parents of a rubber stamp set fostered a lifelong fascination with printed letters and stamps. With his cousin Gary Bryant, Curnoe created dozens of comic books as well as maps and structures made of found objects. His growing facility in drawing and modelling was recognized by prizes at the London Hobby Fair. A childhood interest in collecting—postage stamps, toy soldiers, comic books—presaged the adult collector of pop bottles, slogan buttons, books, records, and friends. An interest in maps began in geography class, where he learned about disputes over national boundaries between Canada and the United States. A habit of writing daily journals began in his teenage years, with a cartoon sketched for each day. Curnoe drew on all these influences throughout his art-making career, inextricably linking his art with his life.

Curnoe’s interest in a career as a cartoonist probably led him to enroll in the Special Art Program at H.B. Beal Technical and Commercial High School in London, Ontario, in 1954. There, his teachers introduced him to avant-garde art and literature, from Dada, Cubism, and Surrealism to authors such as James Joyce, Franz Kafka, and T.S. Eliot and to composers Igor Stravinsky and Béla Bartók. During this time, Curnoe and his father built his first studio in their basement. The sign on the door read “Curnoe’s Inferno.” Like all his later workspaces, this one became a meeting place for friends, including artists Larry Russell (b. 1932), Don Vincent (1932–1993), and Bernice Vincent (1934–2016). The parties were legendary.

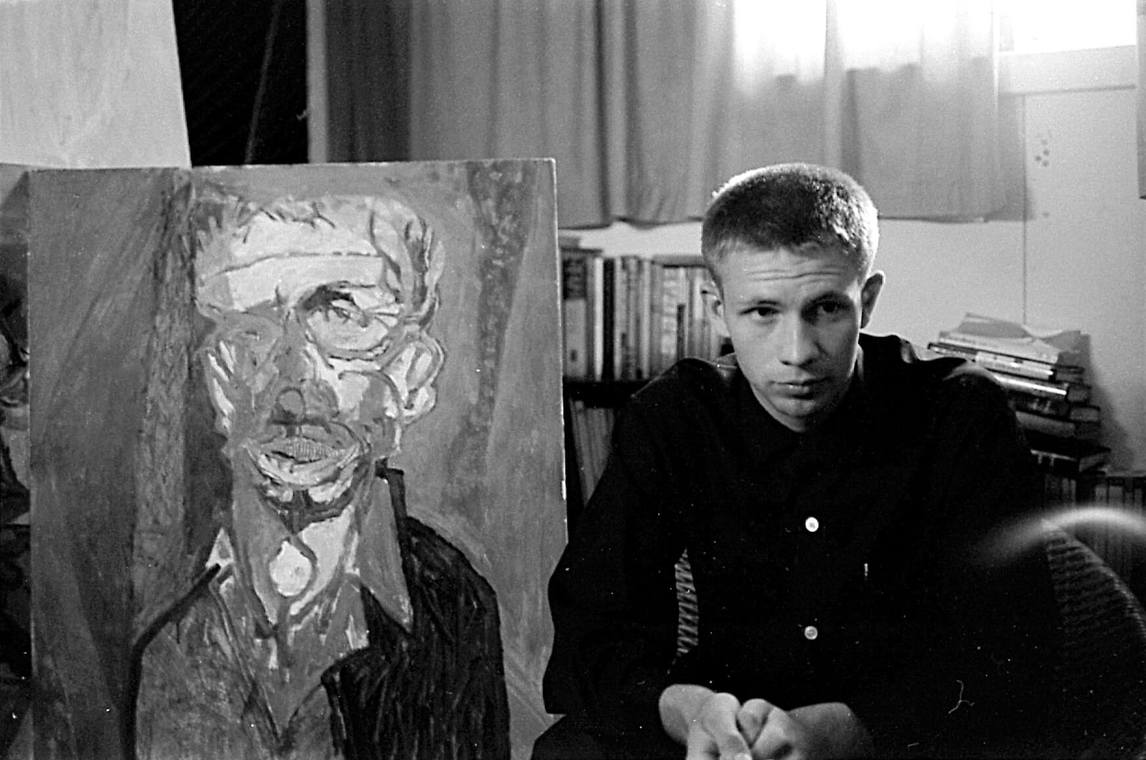

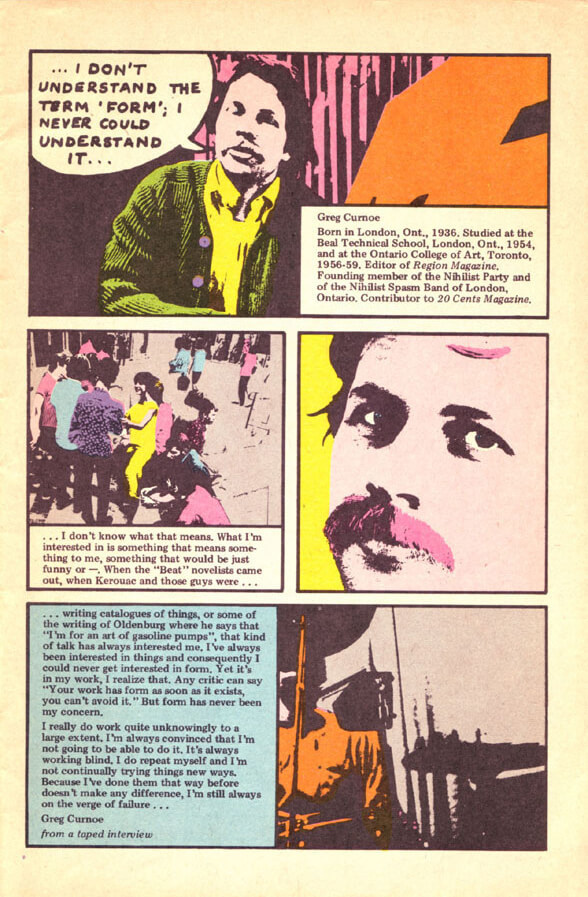

In September 1957 Curnoe began three years of study at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto. It was not a good fit. Curnoe recalled, “OCA was dull. It was also sterile. The instructors were formalists, pure and simple . . . OCA was into form and nothing more. They’d forgotten about content. I guess I was in a rebellious mood but you can only talk about a certain shade of grey for so long.” In fact, Curnoe failed his final year. Somewhat chastened, he returned home. However, those years in Toronto had been productive in other ways. In December 1957 he had helped found the Garret Gallery, an artists’ cooperative. A chance meeting in 1958 with Michel Sanouillet, one of the world’s leading authorities on Dada, was to have a lasting influence, with many subsequent conversations about Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) and French writers, as well as critical support for Curnoe’s work.

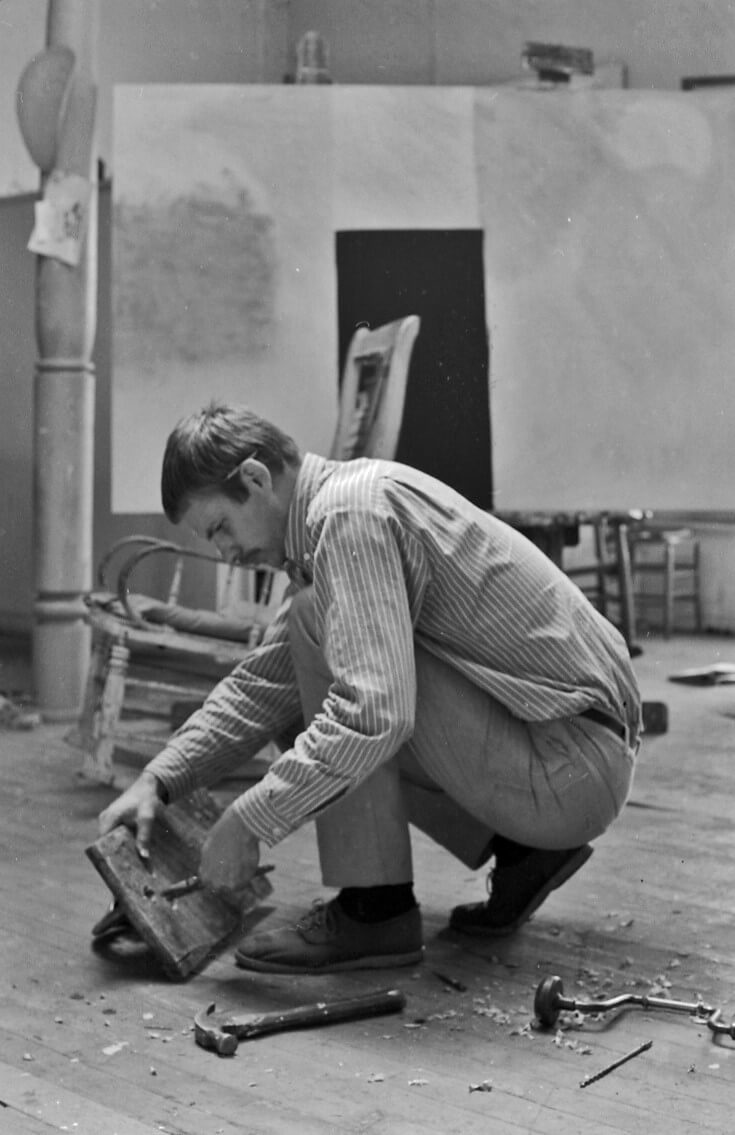

The Artist in His Studio

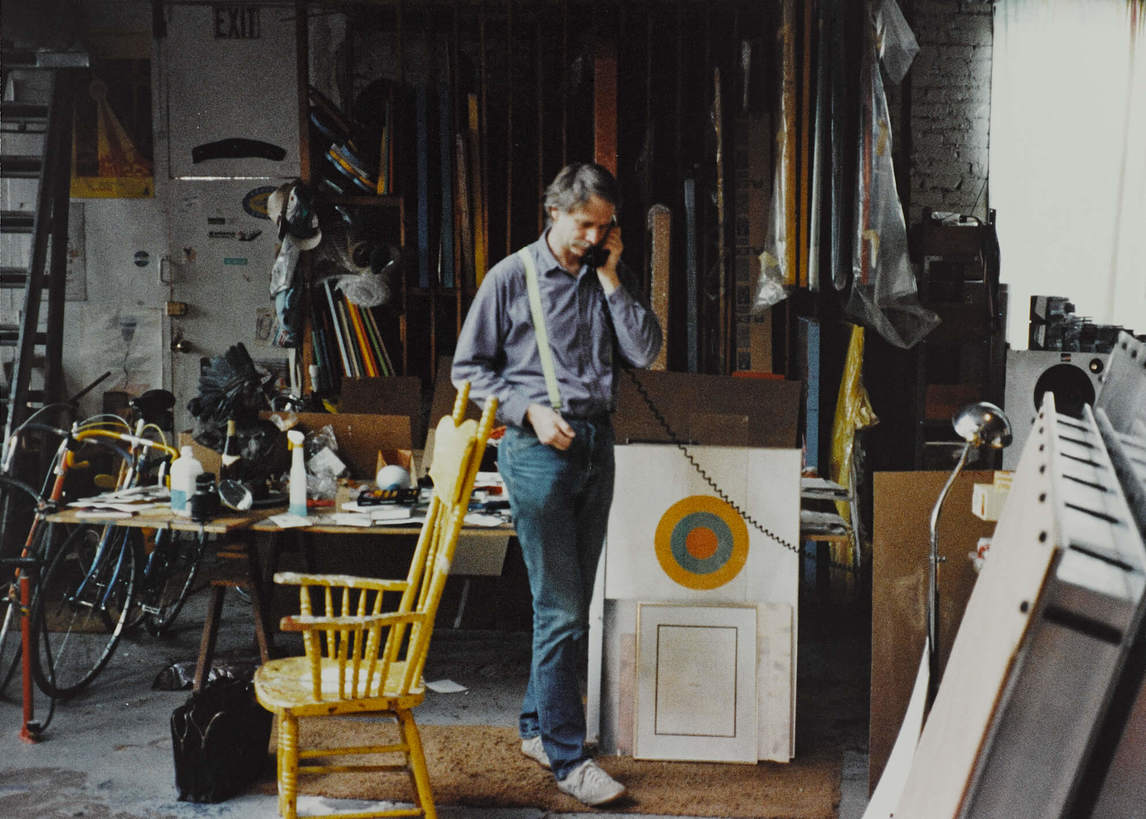

Greg Curnoe returned to London in May 1960 and worked for the summer in the city’s Surveys Department. By July, determined to be a full-time artist, he had rented a large space for a studio in downtown London. From that time forward, he supported himself through sales of his work and, when necessary, a variety of part-time jobs. Eventually his income was supplemented by grants and scholarships from the Canada Council for the Arts.

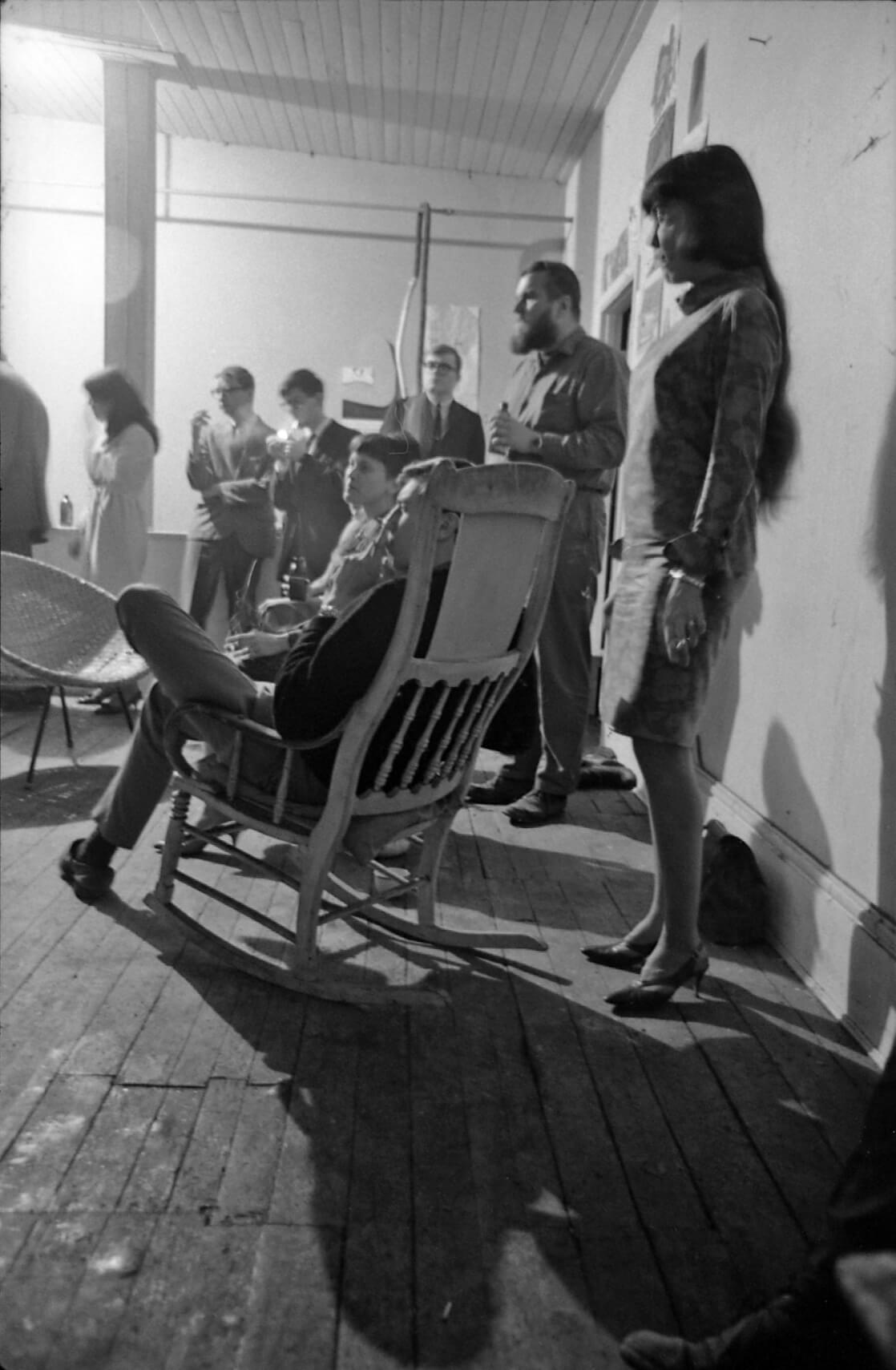

In retrospect, the 1960s could be considered the most productive period of Curnoe’s career. At the centre were his studios. Artist John Boyle (b. 1941) remembered: “He renewed old friendships and sought out new people in the university and the community at large. His studio became a centre of intellectual activity where ideas were discussed and plots were hatched.” Canada had proclaimed a new flag in 1965, and celebrated its centennial and Expo 67 two years later, and those events stimulated debate about Canadian nationalism and a distinctive Canadian identity across the country and likely in Curnoe’s studio as well. At the same time, the growing influx of artists, cultural administrators, and academics from the United States, along with a random violent encounter in New York in 1965, fuelled Curnoe’s anti-American attitude. As artist and curator Greg Hill pointed out, “Curnoe’s nationalism was supported by his regionalism, which was in turn built upon his localism.”

When artist Jack Chambers (1931–1978) returned home to London from Spain in 1961, he and Curnoe became close friends. Other new friends were poet James Reaney and English professor Ross Woodman, who was the first to define the vibrant cultural scene in London in the 1960s as Canadian “regionalism.” Writing in artscanada, the national magazine of contemporary art, Woodman describes Curnoe as “a visionary who has shaped an authentic myth out of the stuff of his region” and regionalism in London as “essentially a region of the mind.” He explained: “Their new regionalism derives in large measure from a desire to avoid the anonymity that they believe awaits those who approach painting as a disinterested problem-solving technical game whose international rules and procedures have been established by the . . . New York School . . . Rejecting the reduction of subject-matter to style, they reach beyond art into life to construct in their work ambiguous images that belong ultimately to neither.” Arts reporter Lenore Crawford, writing insightful reviews in the local newspaper, the London Free Press, also became one of Curnoe’s most steadfast supporters.

Among the many early works Curnoe produced was the painting Tall Girl When I Am Sad on Dundas Street, 1961, which was purchased by the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina in 1962. Curnoe, who was just twenty-five years old, had his first work in a public collection.

At the same time that he was laying the groundwork for a successful career as an artist, Curnoe was establishing himself as a husband and father. After a long series of girlfriends, in 1964 Curnoe met British-born Sheila Thompson and in July 1965 they were married. As Sarah Milroy noted, “Curnoe’s sexual attraction to Sheila was ferocious, and the impact of their union on his creativity was profound. He found her feral and unpredictable, and he was intrigued by her in a way that for him was unprecedented.”

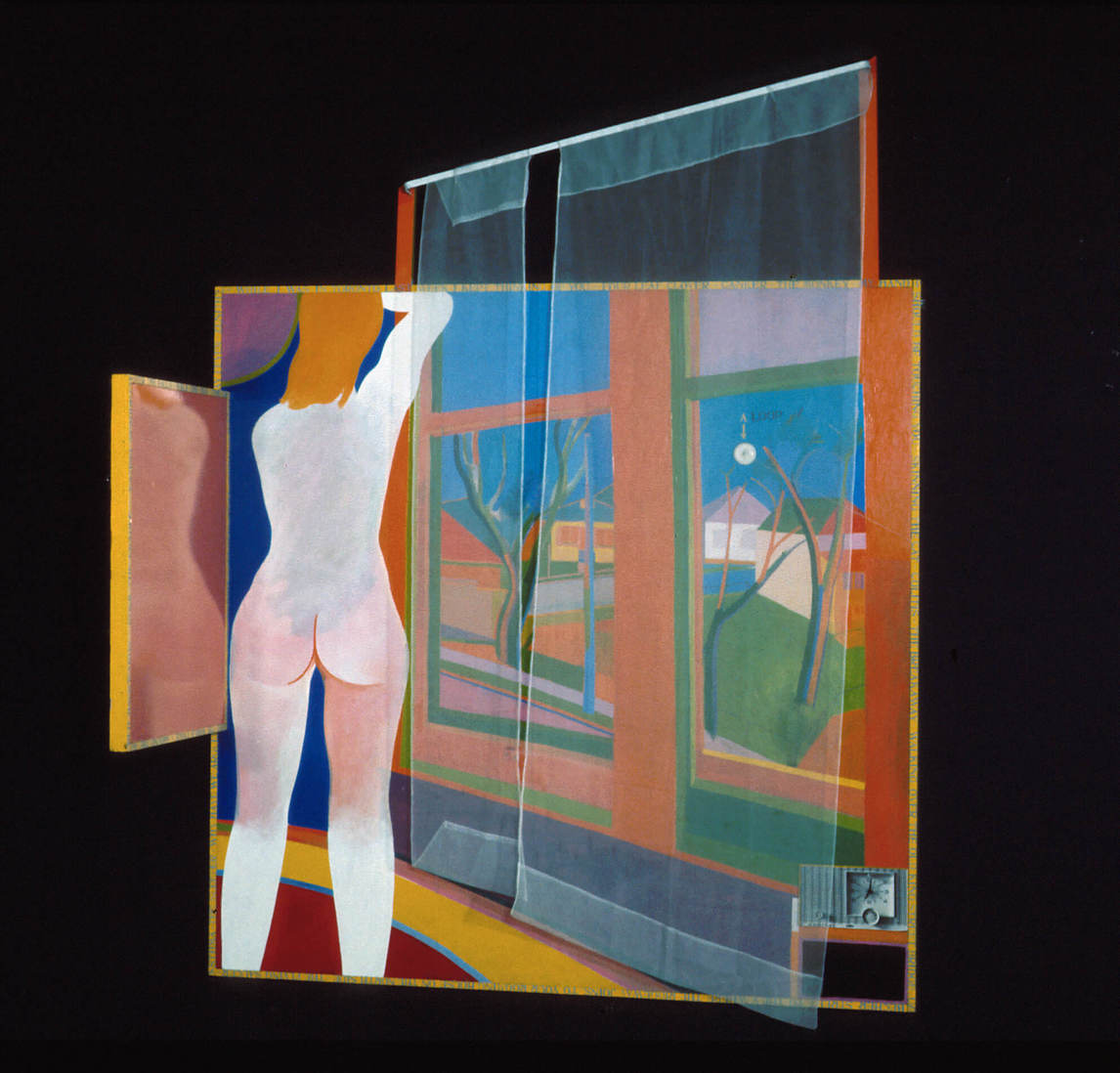

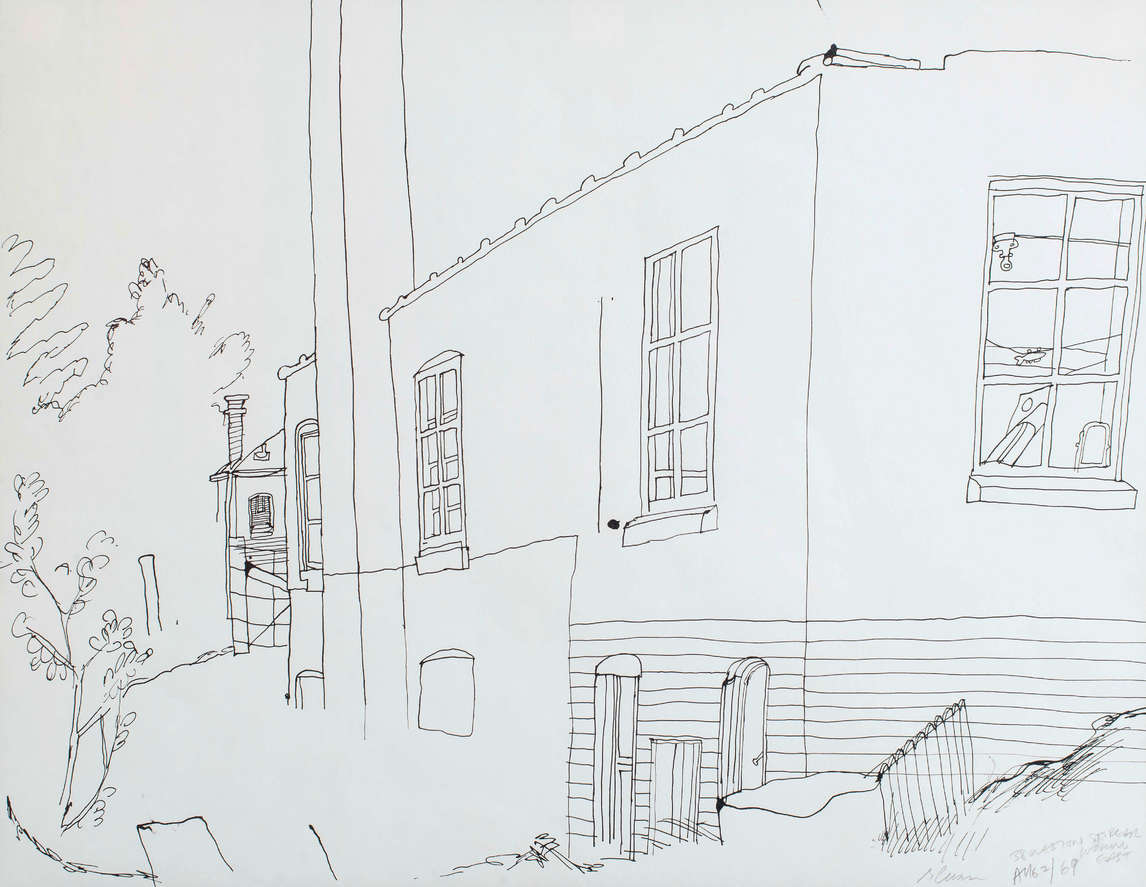

Curnoe had a willing model and muse in Sheila. Their sons, Owen and Galen, arrived in 1966 and 1968 and their daughter, Zoë, was born in 1971. With the purchase of a former industrial building at 38 Weston Street in London, Curnoe had both a home for his family and a studio for his artistic practice. The family occupied the front of the building; the large studio at the rear had windows overlooking the Thames River valley and Victoria Hospital. The views from those windows inspired many works, including View of Victoria Hospital, Second Series, February 10, 1969–March 10, 1971.

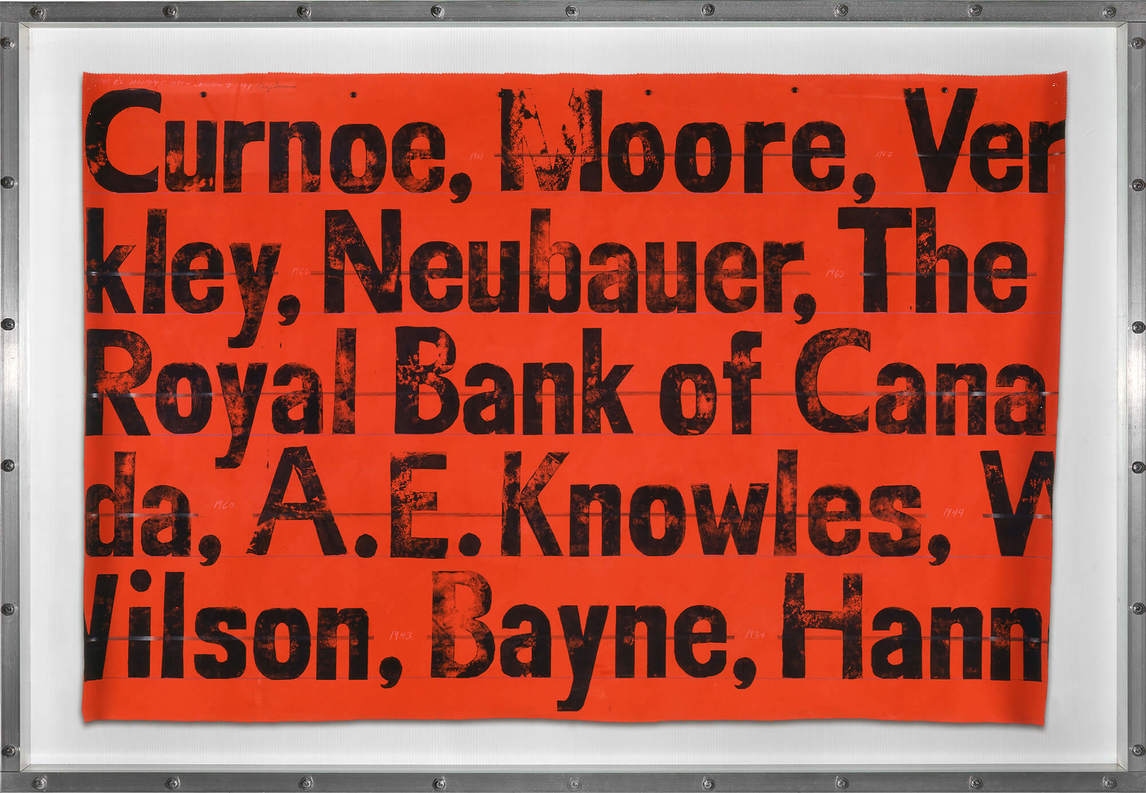

Jake Moore, a prominent Canadian businessman and art collector, bought his first Curnoe work in 1964. Both men came from families that had lived in London for several generations; they shared mutual interests and ideas, including a passion for Canada. Moore’s extensive collecting of Curnoe’s work provided some financial stability for the artist. As art historian Madeline Lennon explained, “They worked out a business-like, but relatively informal, arrangement whereby Moore agreed to purchase a number of finished works. This arrangement has been extended or repeated over the years and it seems to have suited both parties.” Although Curnoe was loath to admit it, Moore was effectively his patron for twenty-eight years. It was Moore who enabled the purchase of the 38 Weston Street property by holding the mortgage, which explains why “Moore” appears among the list of names in Curnoe’s Deeds #2, 1991.

National Attention

Curnoe became well known beyond London after he met curators Pierre Théberge and Dennis Reid of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. With bravado typical of him, Curnoe had written to the gallery in 1966, asking that it consider purchasing one of his works for its collection. Théberge, the young assistant curator, had never heard of Curnoe and had no idea of the location of London, but he was sent to visit Curnoe’s studio. Immediately he was impressed by the artist: “In the course of our conversations, I soon realized that Curnoe was highly cultivated. He had the entire range of modern art history at his fingertips.”

The visit resulted in the National Gallery’s purchase of The Camouflaged Piano or French Roundels, 1965–66, which was included in the gallery’s centennial exhibition, 300 Years of Canadian Art. At the opening in May 1967, Curnoe was introduced to Dennis Reid, who later remarked, “[I] remember being not quite sure what to make of his curious mix of hip sophistication and down-to-earth charm.” Curnoe must have made the right impression because early in 1968 Reid included Curnoe in Canada: Art d’aujourd’hui, an exhibition that opened in Paris and travelled to Rome, Lausanne, and Brussels.

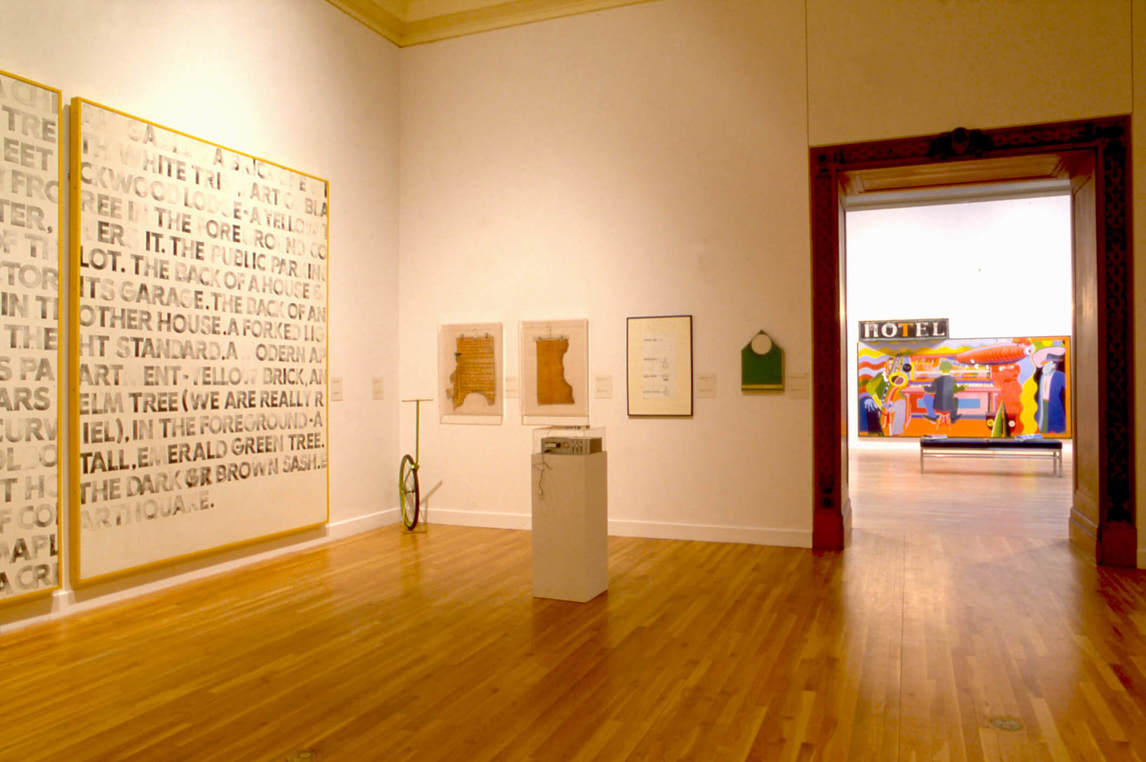

In his characteristic generous spirit, Curnoe made sure that Théberge visited the studios of other local artists on his trips to London. In 1968 Heart of London, a landmark exhibition curated by Théberge, opened at the London Public Library and Art Museum (now Museum London) and toured to eight other small cities, from Charlottetown to Victoria. The National Gallery of Canada was only included on the tour at the last minute. Featured were paintings, sculptures, collages, and constructions by Curnoe and ten other London artists, including Jack Chambers (1931–1978), Murray Favro (b. 1940), John Boyle (b. 1941), Tony Urquhart (b. 1934), and Ed Zelenak (b. 1940). The irreverent spirit of London’s artists, captured by the unusual comic-book catalogue, was critically acclaimed.

By 1970 Curnoe’s works had been seen across Canada and in four international exhibitions. Art galleries across the country, including the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Vancouver Art Gallery; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; and National Gallery of Canada, had purchased his paintings for their collections.

While this was an especially productive art-making period, Curnoe was following his other interests and passions too. In 1969 he began typing his daily journal into a computer at Western University that had been programmed to reflect his stream-of-consciousness style of writing. He envisioned sharing these journals with others, similar to what we do now on Facebook and Twitter. In Paris and in London, U.K., he performed on modified kazoo and drums with the Nihilist Spasm Band. As a cultural activist, Curnoe had taken the lead in founding the small publication Region and then alternative galleries—Region Gallery, 20/20 Gallery, and Forest City Gallery—in his hometown to promote the work of local artists. He was also supportive of the establishment of Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC), to ensure that artists were fairly compensated.

On the Move

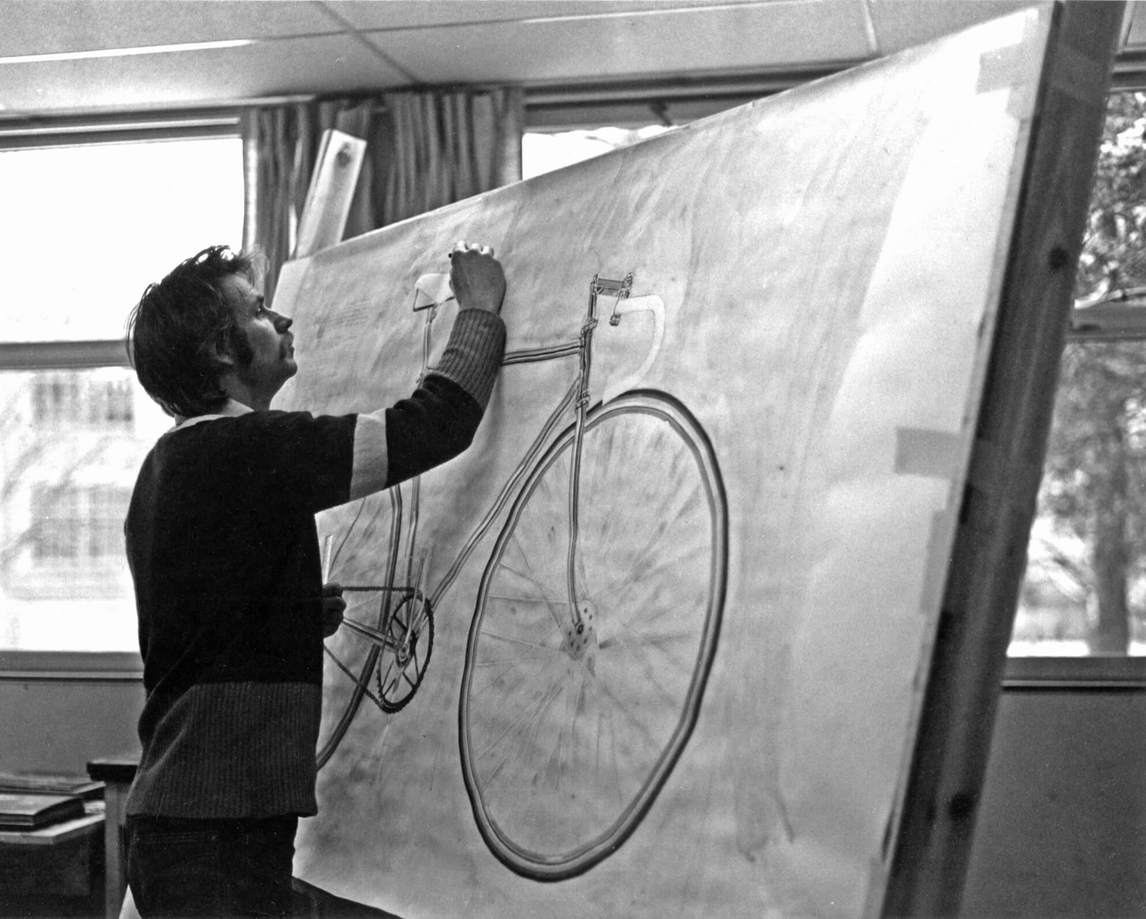

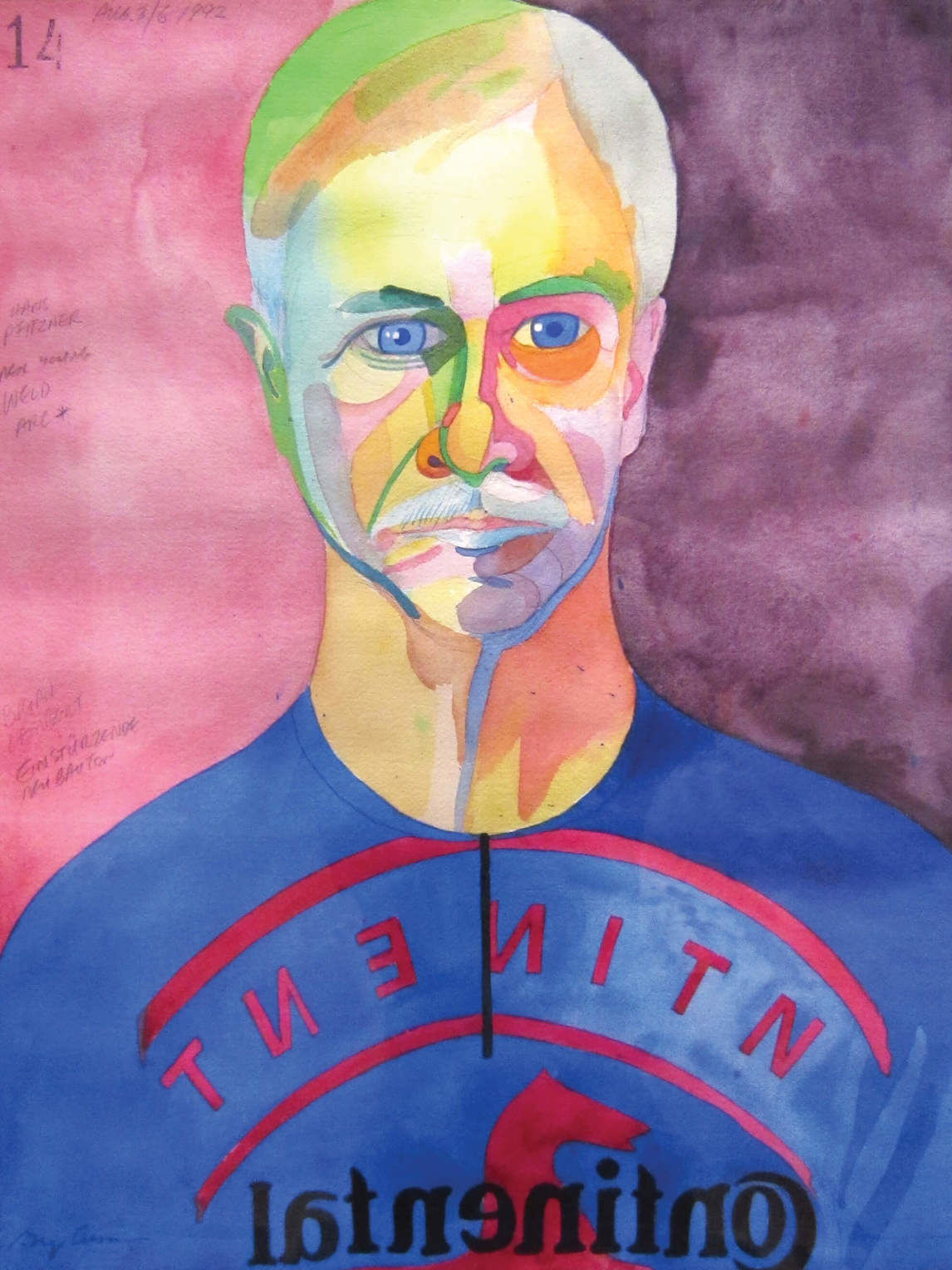

In the spring of 1971 Greg Curnoe rebuilt the CCM bicycle he’d ridden as a teenager, literally changing gears in his life and his work. Initially just forms of transportation, bicycles became a way for Curnoe to express his love of speed, competition, and camaraderie. He bought racing bicycles and joined the London Centennial Wheelers, participating in regular rides and competitions. He won trophies; designed badges, caps, and shirts; and served as president of the club. Not surprisingly, bicycles became the subject of much of his work for the next fifteen years. The first of at least fifteen life-sized bicycle works, the cut-out construction Self-Portrait with Galen on 1951 CCM, 1971, is the only one of these that includes a self-portrait and a portrait of his younger son, clearly showing the connection between Curnoe’s art and his everyday life.

As well as cycling in the London region, Curnoe travelled across Canada as a member of Canada Council for the Arts juries or on short-term teaching assignments at various institutions. He successfully applied for a grant that took him to Baffin Island. In 1971 Curnoe had journeyed from the east to the west coast and from the most southerly point in Canada to the Arctic Circle, wherever possible visiting islands, which he considered bastions of local culture.

Curnoe spent a year at the University of Western Ontario (now Western University) in 1975–76, giving lectures and studio critiques, and interacting with the university community as artist-in-residence. During his tenure he produced approximately three hundred figure drawings, which rekindled his interest in the figure and led to his Homage to Van Dongen series. There were also trips to Europe in conjunction with exhibitions such as the 37th Venice Biennale, a major international contemporary art exhibition in which eight of his “window” works were exhibited, including View of Victoria Hospital, Second Series, February 10, 1969–March 10, 1971. Curnoe documented all his travels in journals and sketchbooks.

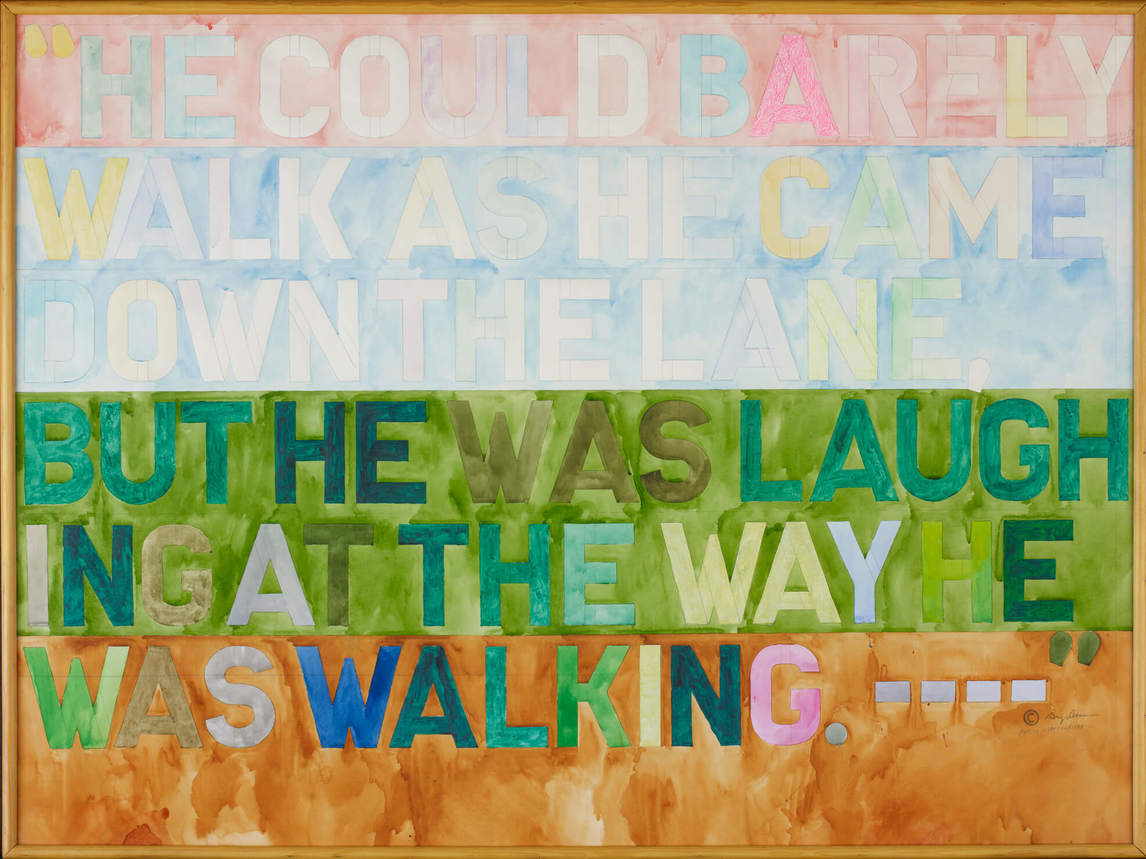

After Venice, Pierre Théberge began to work on a retrospective exhibition of Curnoe’s work for the National Gallery of Canada, in Ottawa. At the same time, Curnoe was affected by the deaths of a number of men close to him, including fellow cyclist and film critic Martin Walsh (1947–1977); photographer Michel Lambeth (1923–1977); artist Jack Chambers (1931–1978); and artist and writer Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979). Curnoe painted “obituary” text works for each of them. The decade that had begun with the new focus on cycling ended with the difficult task of looking back over his career for the retrospective exhibition and perhaps contemplating thoughts about his own mortality.

Retrospective Blues

Greg Curnoe was a national figure by the time the touring exhibition Greg Curnoe: Rétrospective/Retrospective opened in 1981 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, where Pierre Théberge had become chief curator. The exhibition received mixed reviews, many of them negative. Globe and Mail art critic John Bentley Mays wrote scathingly: “The work itself, the actual body of work left over at the end of a hard day of sloganeering, is neither strong nor important enough to pull this retrospective clear of the mire of coarse anti-Americanism, endless ad-hominem attacks on his critics . . . and regionalist sentimentality in which he planted his feet and took his stand, for better or worse, more than two decades ago.”

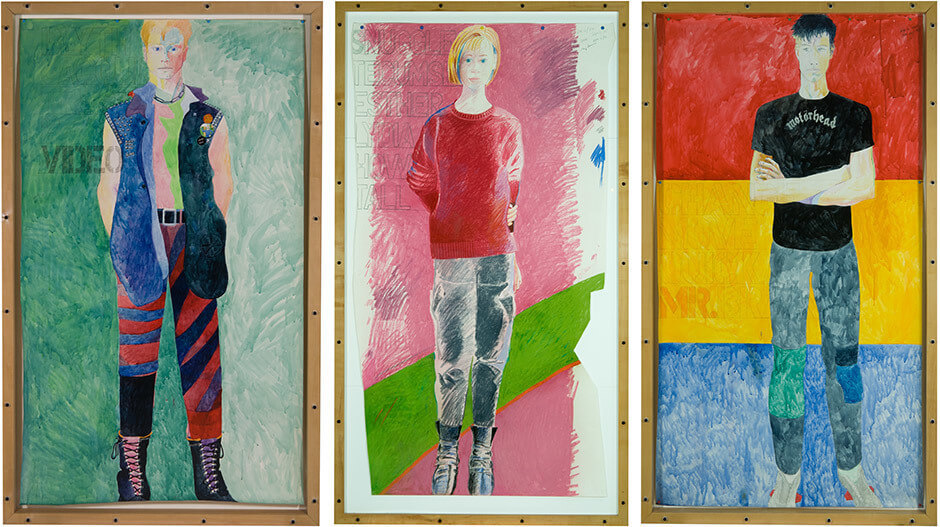

After the retrospective closed, Curnoe was disheartened and could not paint. Then, in Vancouver in 1982, he was blindsided by art historian Serge Guilbaut’s public criticism that Curnoe was objectifying his wife in his nude portraits. It was hard for Curnoe to realize that his concerns had become unfashionable. Cultural nationalism had been replaced by the politics of gender, race, and AIDS. Painting had given way to installation, photography, and video art. He retreated to life-sized portraits of himself, his wife, his children, and even the family dog.

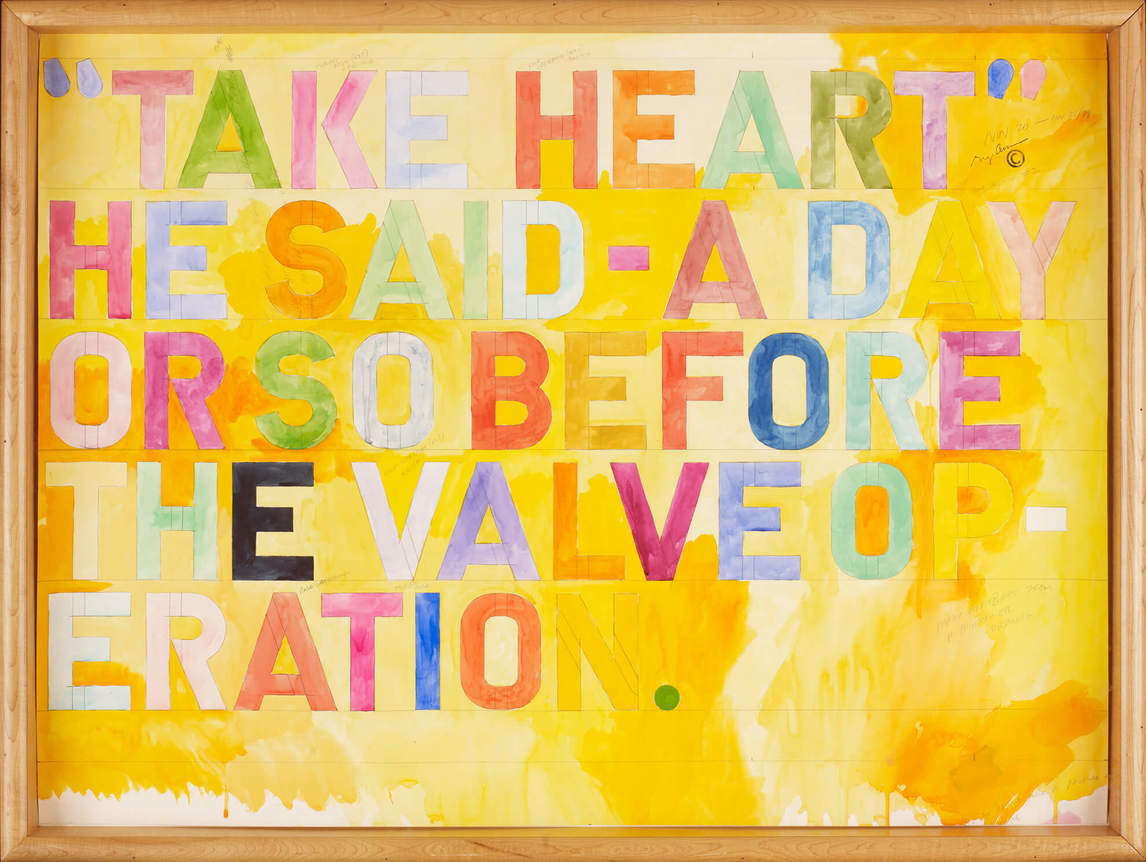

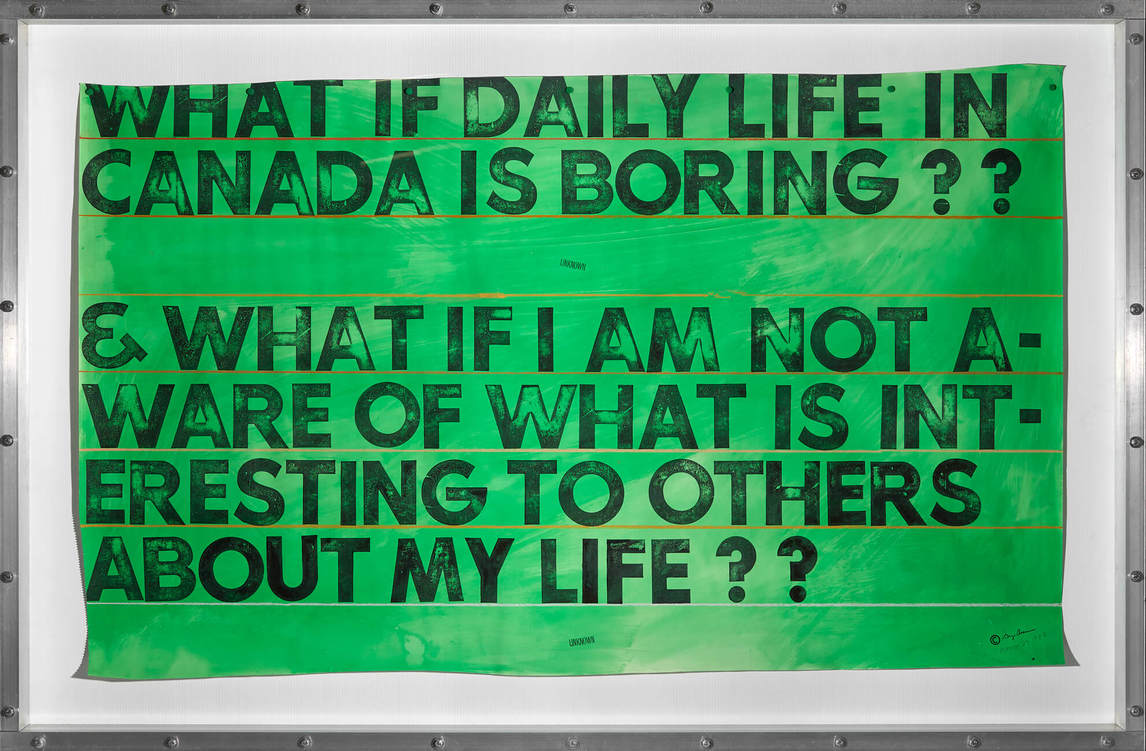

But in 1986 he embarked on new text works shown the next year in an exhibition at the artist-run gallery YYZ in Toronto. Curnoe was obviously questioning his approach. As he wrote in the work Doubtful Insight, March 23, 1987: “What if I am not aware of what is interesting to others about my life?”

His new work seemed to have struck a chord, and the decade ended with positive reviews of his exhibition Rubber Stamped Books and Works 1961–1989 at Art Metropole, an artist-run space in Toronto. Curnoe’s work was introduced to a younger generation of artists, while the publication of Blue Book #8, a nihilist self-portrait, meant a wider dissemination of his lettered work.

Digs and Deeds

In 1980 a dispute over the location of the property line at 38 Weston Street had prompted Greg Curnoe to research the history of his lot.

Ten years later he started to trace the records as far back as he could. Curnoe wondered whether indigenous people had lived on the land he now owned, but finding that local historians knew nothing about the pre-colonial cultures in the region, he began to research the subject himself. Working feverishly, as was his wont when possessed by an idea, Curnoe painstakingly traced the history of the lot and his neighbourhood as far back as 8600 BCE through public records, histories, and interviews. From this material he created the Deeds series of five large text works and, concurrently, organized the information he collected on a home computer in preparation for writing a book about his findings.

Everything came to an abrupt stop on Saturday, November 14, 1992. On a regular outing with the London Centennial Wheelers, riding his favourite yellow Mariposa bike, Curnoe was killed when he was hit from behind by a pickup truck. The news ricocheted through London and across the country.

Several days after Curnoe’s death, many people in the art community were startled to receive an exhibition invitation that read poignantly, “I am UOY: Greg Curnoe, Self Portraits.” Sheila Curnoe decided that the show at the Wynick/Tuck Gallery in Toronto should open as originally scheduled, exactly one week after his death. The artist was present only in his recent self-portraits.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements