A largely self-taught artist, Gershon Iskowitz’s work can be separated into three distinct phases: figurative memory paintings depicting his life before and during the war; landscape paintings from his visits to Parry Sound, Ontario, 1954 to the late 1960s; and from 1960 on, a rapid move into abstract painting. His materials were consistently basic and essential: oil on board or canvas for paintings; watercolour on paper; and ink on paper for drawings. Yet defining Iskowitz’s style is elusive: he never spoke of influences, and his work cannot be mistaken for that of any other artist. He painted his own personal vision—and that makes his art unique.

A Singular Style

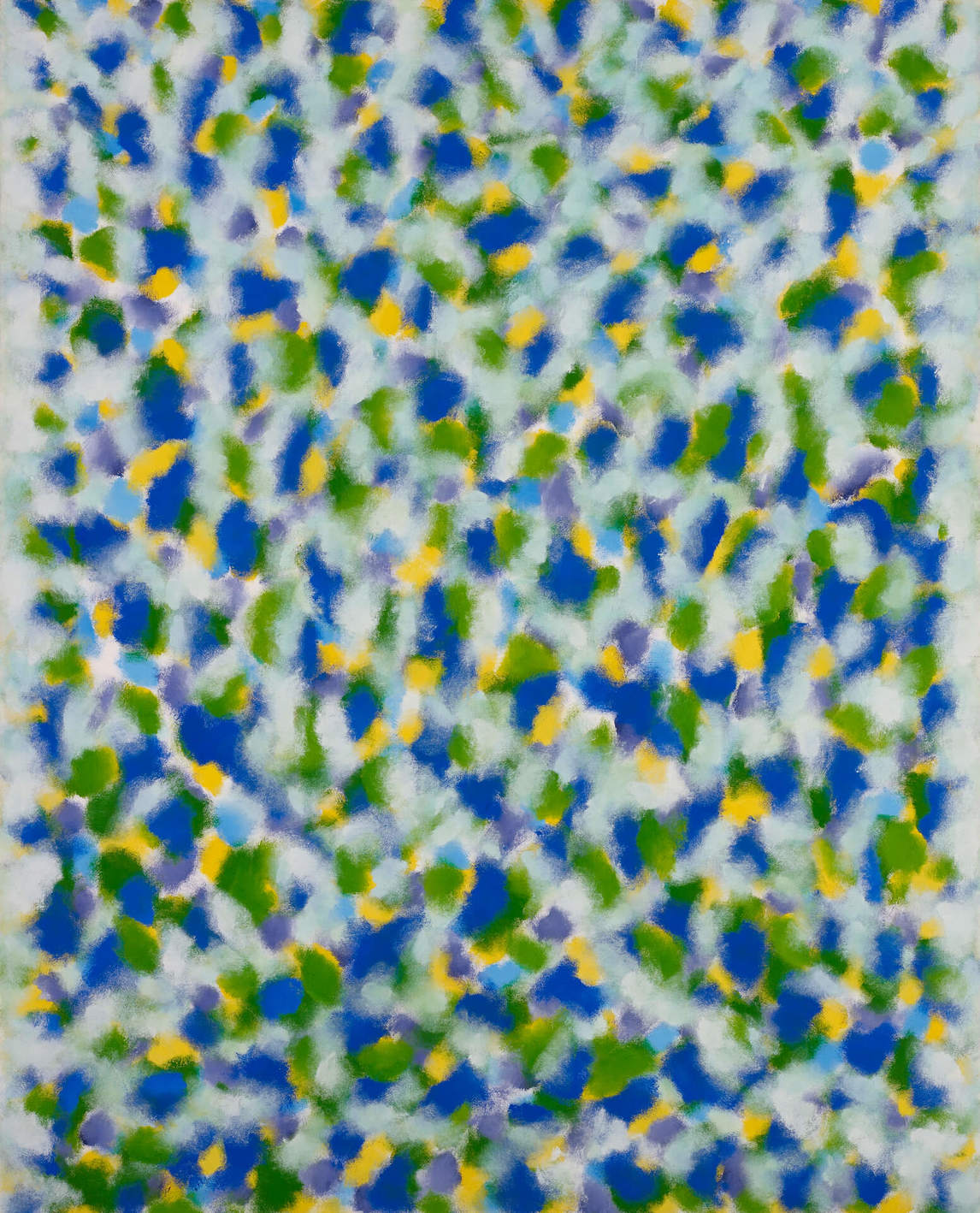

There is an unmistakable “look” to Iskowitz’s work, especially in his abstract paintings. In those final decades of his life, the elements of colour and form in his oeuvre did not vary dramatically, as can be seen by comparing Autumn Landscape #2, 1967, and a late untitled painting from 1987. Nevertheless, his work does not fit easily into any of the contemporary schools and movements—whether hard-edge, minimalism, abstract expressionism, or action painting. Iskowitz was largely self-taught, and he did not borrow from other artists in any obvious ways. Though he expressed an interest in paintings by some other Canadian artists—David Milne (1881–1953), Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998), and Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002)—there is no direct link between their work and his.

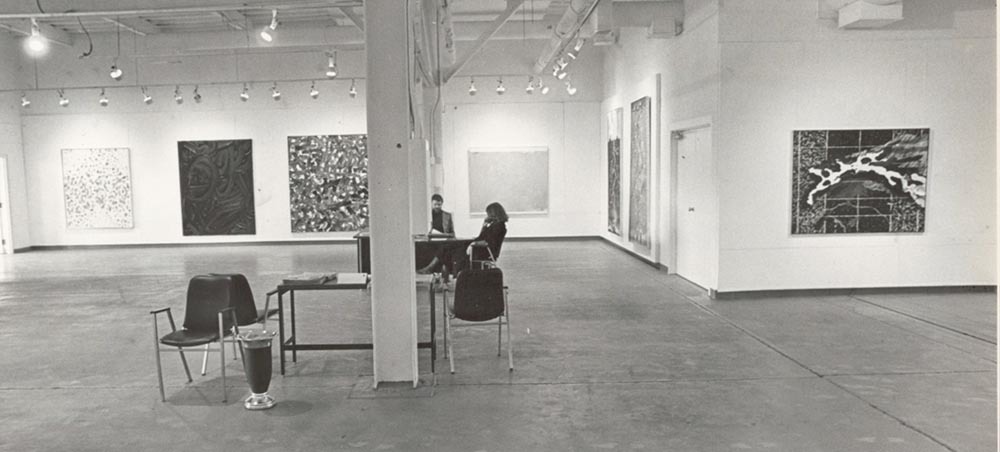

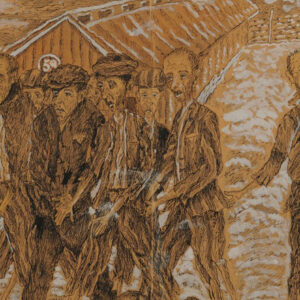

In spite of this self-determination, some art scholars and critics have tried to fit Iskowitz into known categories, ranging from Holocaust artist to colour-field painter. Beginning in 1960 and continuing through to his 1982 retrospective exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario, reviews of his exhibited works often referred to the tragic circumstances of his pre-émigré life—for example, “Gershon Iskowitz: Transmuting Personal Tragedy into Art.” Only three surviving sketches can be positively dated to the war years: Action, 1941, drawn as Iskowitz witnessed the brutality of Nazi soldiers in the Kielce Ghetto, and two from his time in concentration camps: Buchenwald, 1944–45, and Condemned, c.1944–46. Simple and raw in style, these visual documents bear witness to the horrors of the time and express Iskowitz’s empathy with the suffering he observed. They have a strength and integrity that can come only through personal experience. As he waited in the Feldafing Displaced Persons Camp outside Munich in 1946–48 and for some years after his arrival in Toronto in September 1948, Iskowitz worked through his emotions in ink and watercolour memory sketches: images of prewar Poland, such as Through Life, c.1947, Korban, c.1952, and Market, c.1952–54; of events that took place in the Kielce Ghetto, such as It Burns, c.1950–52, and Torah, 1951; and of camp experiences, including Escape, 1948, and Barracks, 1949.

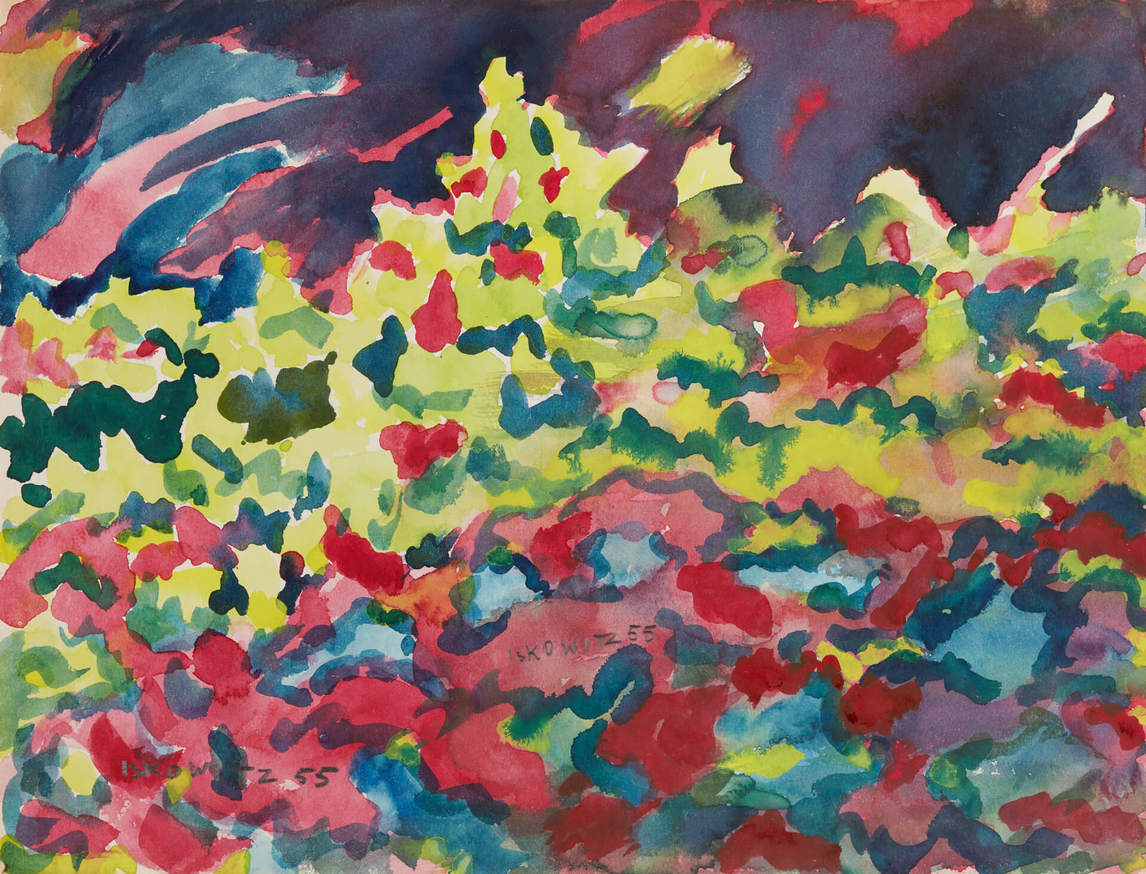

Eventually, Iskowitz began to paint interior scenes and floral still lifes—for example, an undated, untitled 1950s floral painting in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario. These images, along with Parry Sound landscapes such as Summer and Street Scene Parry Sound, both 1955, can be compared in some respects with works by other artists such as Kazuo Nakamura, who took a contemporary approach to landscape. Rather than creating a pictorial view, they painted beyond landscape as nature, and into the nature of painting itself. As Iskowitz noted years later, his Parry Sound landscapes were more important for starting a new life and his personal sense of renewal—not to “paint like the Group of Seven”—than for adapting to the styles and subject matter of art in Canada. In this way, they too are autobiographical.

As Iskowitz’s work began to garner attention and approval by the late 1950s (tellingly, there are no bad reviews), he remained a complicated fit within the context of Canadian art and Toronto artists at the time. He never belonged to any artist group, such as Painters Eleven. Between 1954 and 1960 he exhibited five times with the Canadian Society of Graphic Art, but he regarded this association as an opportunity rather than a shared artistic objective. Even when he was selected for large group exhibitions in the 1970s—including Toronto Painting: 1953–1965 for the National Gallery of Canada in 1972, and the Exhibition of Contemporary Paintings by Seven Canadian Painters from the Canada Council Art Bank, which toured to galleries in Paris, New Zealand, and Australia in 1976 and 1977—he shared no common style with the other artists. Indeed, Iskowitz’s resolute individuality may stem from the way he worked in his studio every night: his method was not to observe but “to experience the experience.”

The critics who reviewed Iskowitz’s paintings in early exhibitions expressed admiration for his work through his subject matter and his relationship, as they perceived it, with the Canadian landscape. Colin Sabiston praised the images in the March 1960 Here and Now solo show as “a sonnet in paint—a poet-painter’s love poem to the spacious freedom of Canada’s land, waterways and skies.” A year later, reviewing another show at the same gallery, Robert Fulford expanded on this idea:

Gershon Iskowitz is the sort of painter who inspires words like “lyric,” “mystic,” “poet-painter,” etc. . . . Again, he offers abstract landscapes, painted in rich evocative waves of color. Again, the colors are soft, the construction is horizontal. But in a few other pictures he veers towards the romantic . . . he is evolving what seems likely to be one of the lasting personal styles of this time and place.

Whenever Iskowitz was asked about his later work, he replied in generalities—that his paintings, even his abstracts, were real: “I see those things,” he said, going on to explain that his challenge as an artist was to put all the parts together. “Everything has to be united.” Certainly he found inspiration for his work in the Canadian landscape, whether on the ground around Parry Sound or from above as he flew over the northern boreal forest and Hudson Bay. Yet, as his paintings became totally abstract in the last two decades of his life, he created his own distinctive landscape, as much looking up to the sky as looking down on the ground, such as in Summer in Yellow, No. 1, 1972. It’s also possible that these abstracts are not only a new kind of painting. They may be formal compositions of light and space, or they may even be another kind of memory art. Iskowitz spoke of continuity in life and how, as he worked alone at night, he reflected on his early life with his family and friends in Poland. Whatever the source, the brilliantly coloured shapes that fluctuate in and out on his canvases are his own unique inventions.

If Iskowitz’s abstract works are indeed multilayered in their meaning, they fit well into the current reappraisal of the term “Canadian Art.” In 2017, Canada’s sesquicentennial year, the National Gallery of Canada published Art in Canada, a new volume on its collection. In it, director Marc Meyer asked: “How Canadian is Canadian art? Is there such a thing, beyond the Canadian passport of the artists? Would it make more sense to talk about art made in Canada rather than presume such a thing as ‘Canadian art?’”

Iskowitz always seemed unconcerned with what was said or written about his work, and he accepted it without known comment. When interviewed, he spoke simply of being human and of his work as an expression of his being. As curator Roald Nasgaard wrote as he reflected on Iskowitz’s work, “The interconnectedness of [his] art and life . . . is fluid and immeasurable.”

Pure Expression

With works such as Parry Sound I, 1955, Iskowitz turned away from the pictorial depiction of what he observed to “pure” painting—the act of creating as an expression unto itself. Theodore Heinrich writes that Iskowitz’s “action of pure painting” was a process and “intuitive, each stroke dictating of inner necessity its answer and successor.” At the time of the retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1982, curator David Burnett described Iskowitz’s work as “rooted in the directness of experience.” He traced this thread from the early figurative memory works such as Escape, 1948, Torah, 1951, and It Burns, c.1950–52, through to the later abstractions. Explosion, c.1949–52, an early example of the bridge between his figurative and abstract works, reveals this transition. “The strength and value of Iskowitz’s work lies in the absolute and naïve unity between his subject matter and its painterly manifestation,” he wrote. “It lies in the essential singleness of his artistic expression.”

This “essential singleness” for Iskowitz was the same, regardless of the different styles of work he produced. Burnett also qualified “naïve” not as “an ignorant roughness” but as Iskowitz’s unwavering focus and the self-directed discipline of his studio routine—“the drive that necessitates his working day in and day out.” When Iskowitz turned to the act of painting, working exclusively within the confines of his studio and no longer needing to create memory images (as in the drawings Ghetto, c.1947, and Memory (Mother and Child), c.1951) or observe the forms in nature (as in an untitled flower painting from 1956), painting became his nature—it spoke for itself, without his having to explain hidden meanings.

Burnett concluded that Iskowitz “came to recognize that expression in painting lay in the activity of painting and that the reality of communication came through the painting itself and not the particular subject matter.” Iskowitz referred to this unity between an artwork and the act of painting in an interview he did with his artist friend David Bolduc (1945–2010): “Every form of art is the image of life,” he said. “There has to be a certain kind of reality in it.” Years earlier the noted Swiss artist Paul Klee (1879–1940) made a similar self-revelatory comment while painting in Tunisia in 1914: “Colour possesses me. I don’t have to pursue it . . . colour and I are one. I am a painter!”

Colour and Shapes

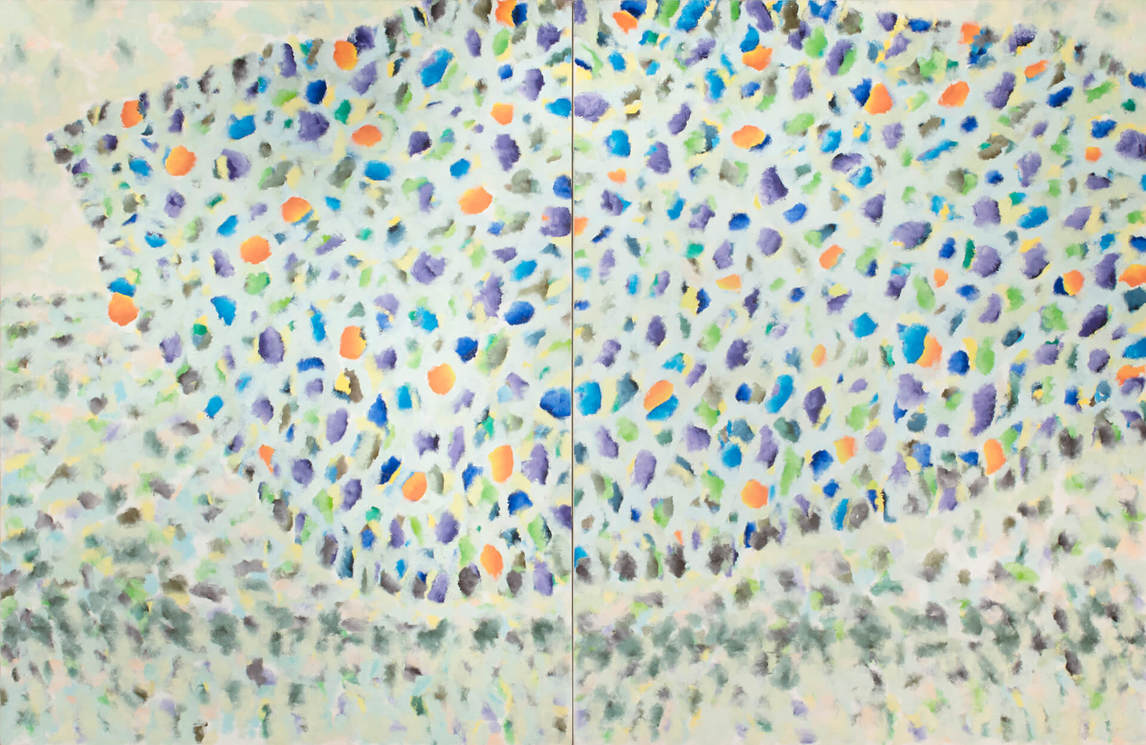

With works such as Late Summer Evening, 1962, Iskowitz started to move toward abstraction, although the compositions retained elements of the pictorial. As his work became fully abstract by 1967—initially with images such as Summer Landscape #2—writers began in the 1970s to analyze Iskowitz’s painting process, focusing on his particular use of colour and his inventive shapes. In an early 1971 feature article for artscanada magazine, Peter Mellen wrote:

After looking at [Iskowitz’s paintings] a long time, colors begin to fluctuate. Some come rushing out to you, others pull you into the depth of the painting. They appear to come alive before you, glowing with vibrant luminosity. Real space becomes infinite space—space through which you can float weightlessly.

Three years later, critic Art Perry also analyzed Iskowitz’s use of colour:

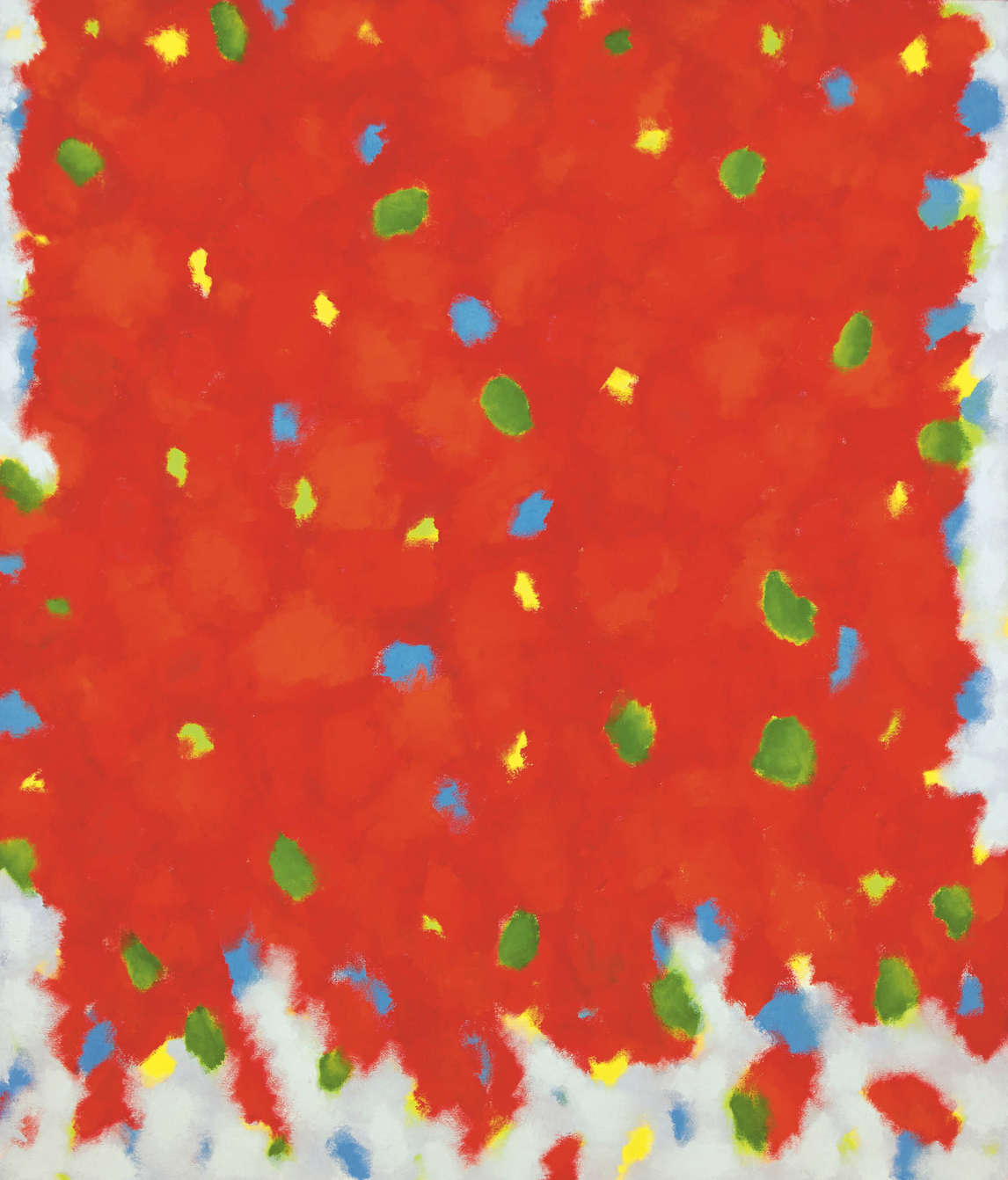

An Iskowitz red is dissimilar to any other red. It is a hyper-red, a supersaturating red, an individually and sensually encompassing red. And not to discredit Iskowitz green, mauve, blue or purple, they too have no visual counterpart. To view a color-field painting by Gershon Iskowitz is to re-experience color. Through a subtle juxtaposition of catalyst color dots and his mottled color-fields, Iskowitz not only controls but activates the whole painted surface [to] make it vibrate at a higher intensity: Iskowitz is probably Canada’s finest color engineer.

The colour-field painters emerging in the United States in the 1940s had been of great interest to the Toronto abstractionist collective Painters Eleven in the 1950s. The influence of expressionist-based versions of the style was evident in the work of Jack Bush (1909–1977) and Oscar Cahén (1916–1956) in particular. Exhibitions by Americans Jules Olitski (1922–2007) and Frank Stella (b.1936) at David Mirvish Gallery brought the evolving style to Toronto critics and audiences. Iskowitz did not identify as a colour-field painter—or with any category or school. Still, some critics used this term in discussing his abstract works: it enabled them to focus on the innovative use of colour that became his hallmark. Art historian Dennis Reid, for instance, describes the watercolour Summer Sound, 1965, and other similar pieces, such as Tree Reflections, 1960, as landscape and colour-field paintings.

Merike Weiler focused on the duality she experienced in 1975 as she viewed Iskowitz’s works in his first public gallery exhibition at the Glenbow-Alberta Institute in Calgary:

In his work I see a recurring process, an alternating though uneven rhythm between structured and unstructured shape . . . . For me, Iskowitz is a duality, a curious blend of alienation and ebullience, at once an ascetic and a sensualist. In the same way, his paintings are a revelation and a camouflage.

In the 1970s art historians presented two different perspectives on Iskowitz’s work. Roald Nasgaard made an analogy between Iskowitz and the Romantic, lyrical sublime, especially with the German painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840). Theodore Heinrich focused on Iskowitz’s painting process (how he applied paint) and working method (the solitude and discipline in his studio) but also added a wry analogy: “As in the October canvases, [the forms] avoid becoming islands by touching an edge in peninsular fashion, much the way Spain clings to Europe while turning its back on it.”

Drawings

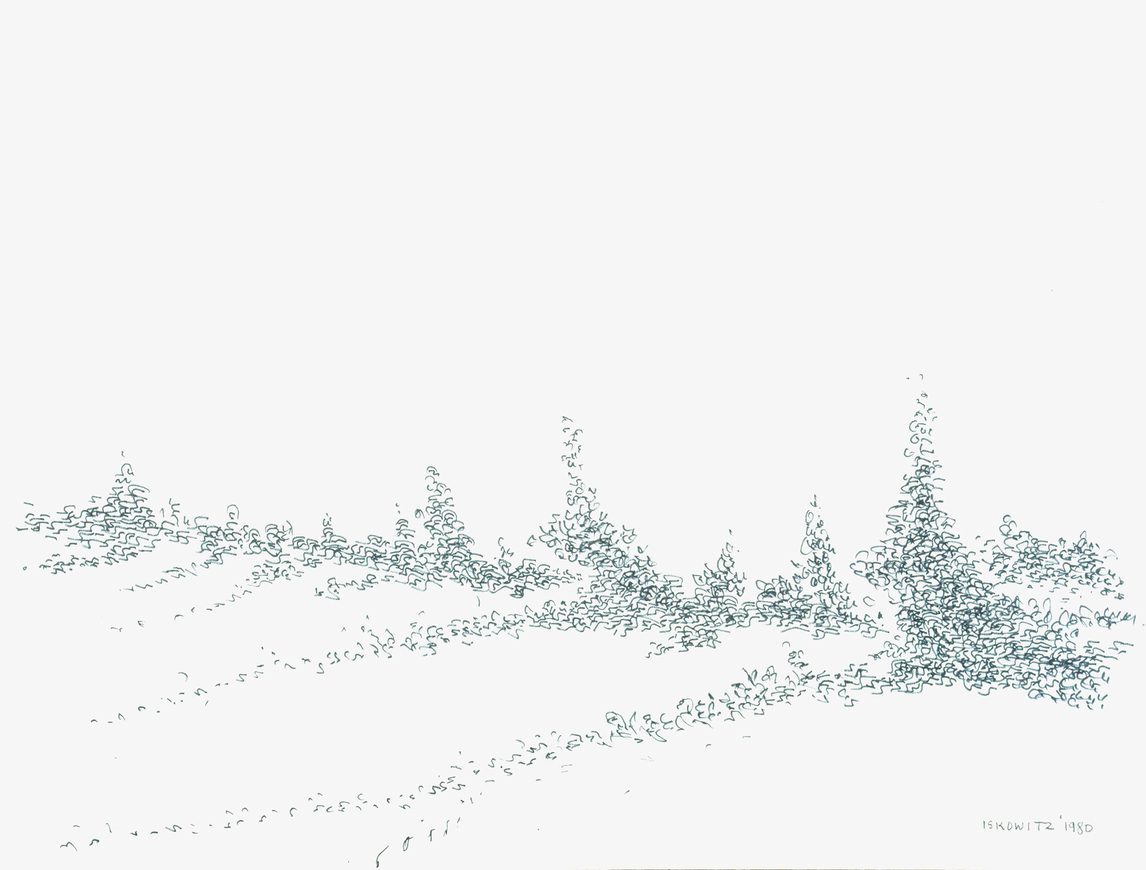

While Iskowitz never made preliminary drawings for paintings, drawing was a lifelong and parallel activity for him. His earliest work, done in Poland and Germany during and immediately after the war, could only be drawing, given his limited art materials and the urgency he felt to record impressions and memories. He continued his memory drawings after he arrived in Toronto and into the early 1950s. In this same period he also made quick life drawings (nudes) and sketches of Toronto street scenes, but thereafter he focused on two distinct subjects: portraits and landscape. By 1951 his portrait drawings took on a consistent style that continued until the last dated work in January 1987. They are immediate contour sketches that capture the essential features of his subject, without any shading or toning. Most of them are of women.

In contrast, his landscape drawings did change in style. The earliest, dated 1952, are vigorous gestural drawings done in felt pen. By 1962 Iskowitz developed a “pointillism” style, using short strokes done in ink. He never exhibited the portrait drawings: he did them for himself and sometimes gave them to the sitter. In 1981, however, he asked Gallery Moos to feature a group of the later landscape drawings in an exhibition.

These drawings, a series of landscapes that make use of the pointillist style and combine it with tiny ovoid line work, reveal the breadth of Iskowitz’s late-career technical abilities. While Iskowitz was often considered a methodical colourist, his command of drawing technique shows a keen eye for space and detail communicated through minimal arrangement and repetition. As seen in Landscape #2, 1980, the composition is achieved through a bold central feature that is distinguished by vertical spires contrasted with waning diagonal lines to invoke the pitch and horizon of a landscape. The works from this 1981 exhibition offer a rare glimpse into the artist’s relationship with the land—intimate and controlled. Like his paintings, the landscape drawings are an Iskowitz studio invention, an idealized view of an imagined world.

A Measured Technique

For all the apparent simplicity of the abstract paintings Iskowitz was creating by the late 1960s, he achieved these results in complex and varied ways. Deep contemplation and detailed execution were required for both the ovoid and blip forms in Autumn Landscape #2, 1967; Orange Yellow C, 1982; and Northern Lights Septet No. 3, 1985, and the organic contours of large cloud or galaxy forms in Uplands E, 1971; Uplands H, and Uplands K, both 1972; and Little Orange Painting II, 1974.

Iskowitz spoke of painting layers upon layers, but the ovoid and blip forms were not always the last layer he applied. Sometimes he brushed a background colour onto the surface to create these forms, as in the detail of Lowlands No. 9, 1970, and Newscape, 1976. Other times he painted the forms directly onto a coloured ground, as in the alternative detail of Lowlands No. 9 (in this case, Iskowitz is using both the brush techniques in one painting) and in an untitled 1987 painting. The 1987 painting also has subtler forms, yellow on yellow. These techniques are Iskowitz’s own invention, and they cannot be mistaken for those of any other artist.

Dennis Reid writes that Iskowitz had only to “alter colours and their configuration in order to achieve a limitless variety of moods and feelings.” That is true for his 1977 watercolours, which were made with instant and direct “drops” of colour on dampened paper. An untitled watercolour in the collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts uses green, yellow, and blue; in another, entitled AK, 1977, the red is dominant, whereas the yellow recedes in the untitled work and the blue and green are dominant.

Iskowitz applied no formula, but he registered the nuance of technique in the final work, as all high-functioning painters do. Like virtuoso musicians, they know what they want to achieve. The difference between the best artists or performers and their myriad competent followers is in the mind. To be “in the music,” as Iskowitz was “in the painting,” is “to experience the experience.”

Harry Malcolmson remembers Iskowitz as an unaffected person, deliberate in manner yet also spontaneous. He recalled a gathering at artist Les Levine’s (b.1935) New York studio in the early 1980s that included Iskowitz, following the opening of the Canadian’s New York solo exhibition. As the conversation progressed, Levine declared that artists had to have in mind what they were going to do. Iskowitz replied that before artists could begin to work, they had first to clear their minds and approach the canvas blank. In Malcolmson’s interpretation, although Iskowitz did not begin a painting with a complete image in mind, his approach was methodical, and the final composition emerged only as he progressed.

Style and technique were inseparable for Iskowitz. He built up his paintings with layers, and as he made adjustments to shapes and contours, he never overpainted in order to generate impasto texturing. Works such as Ultra Blue Green, 1973, are an accomplished example of this technique. All his paintings were rectilinear, never square, with only two exceptions, the arch-topped three-panelled work Uplands, 1969–70, and the 1985 Septet series. As Daniel Solomon (b.1945) wrote: “Gershon’s studio practice, like everything in his life, was simple and stripped down. He used Stevenson’s oil paint and bristle brushes, as basic as you can get. He had people who stretched and primed his canvas.” He did not mix media, nor did he engage in any hybridization or pastiche of forms. He found what worked and kept to it, and he never experimented for the sake of novelty.

Two Iskowitz interviews—one with David Bolduc (1945–2010) and the other with Merike Weiler—offer a direct sense of his thoughts and voice. In 1974 with Bolduc, Iskowitz spoke about the process of painting as a living experience and emphasized that he did not follow any critical theories or doctrines:

Whenever I put on a coat of paint I look at it and say: well, let’s leave it until tomorrow, when it dries; and tomorrow I’ll put on another coat and . . . let’s leave it. Then I put on one coat—ten coats—fifteen—twenty—it depends. Then I say it’s finished. That’s it; I can’t work anymore.

All paintings, if they’re good paintings, have skill, form, space, colour. It’s like a landscape, a form of life. Every form of art is the image of life. There has to be a certain kind of reality in it. It can be . . . just a few blobs of paint, but it has to be a form of communication. My work is more like . . . space, and poems; and it relates to my daily living. What we do is paint; we build an image, a form. It’s not an obvious form, it’s private.

I never look at drawings when I paint, they’re just to get some ideas. Painting is entirely different . . . a direct approach. If I had to look at a little drawing and then blow it up—it would be awful. The painting would be dead, a blown-up thing.

In 1975 with Weiler, Iskowitz offered a similar commentary, emphasizing the daily life and working only at night, and what was revealed to him as he worked:

The only fear I have is before starting to paint. When I paint, I’m great, I feel great. You reflect on your own vision. That’s what it’s about. You put in your own intelligence, your own expression, your own ability. You put yourself in any form of art. I just paint; I see and I feel and I want to be honest. It’s very important; you make what you believe. It’s like a plastic interpretation of life.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements