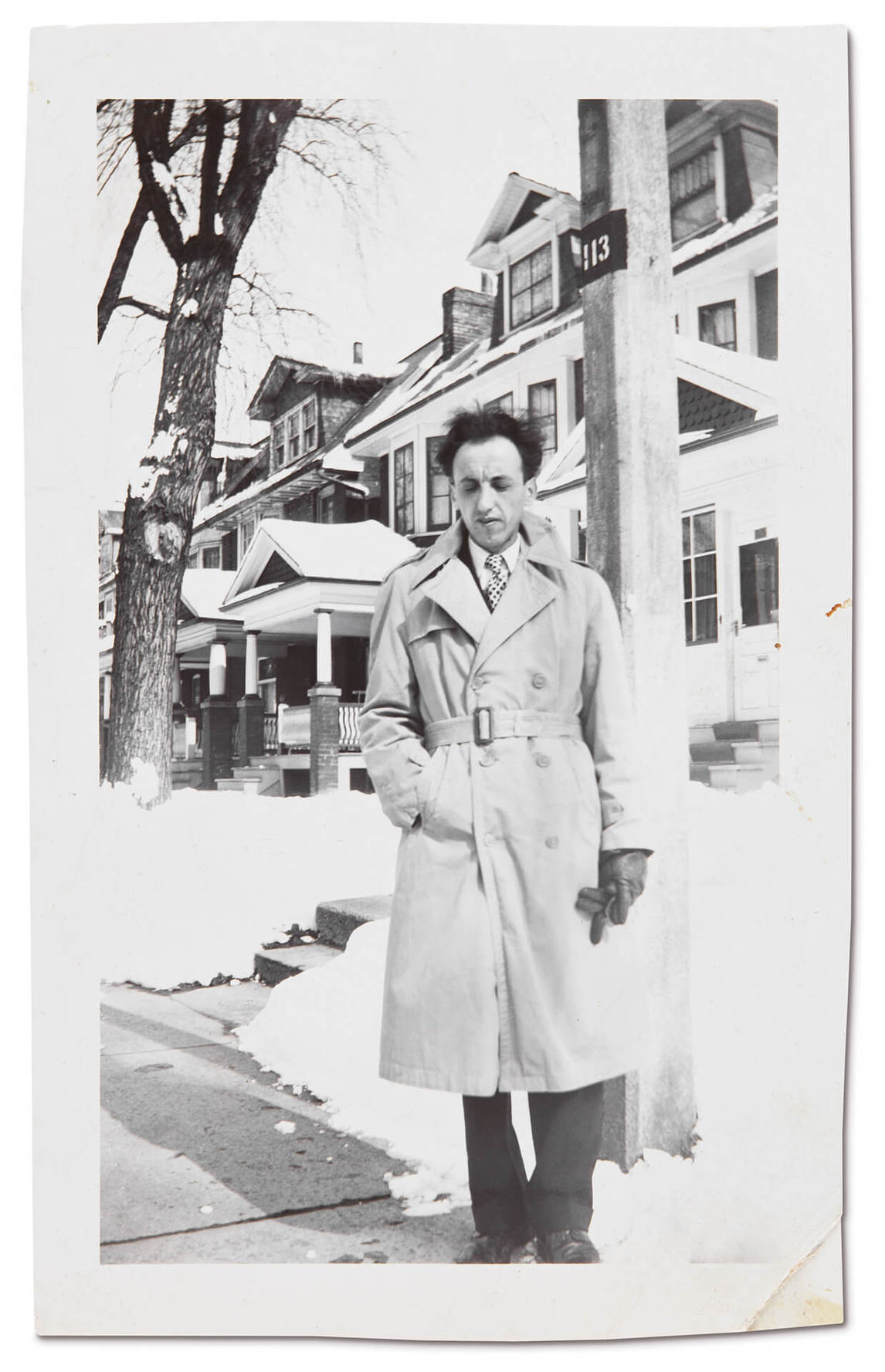

As a survivor of concentration camps in Poland, Gershon Iskowitz became a witness to the Holocaust in his drawings and memory works from the years 1941–54. After some time in Canada, he began to paint landscapes around Parry Sound, though his expression vastly differed from the Group of Seven’s nationalist ideals. A breakthrough came in 1967 after a flight to Churchill, Manitoba, when he discovered his unique Canadian landscape in abstract panoramic images of land and sky painted in brilliant, luminous colours. Although he was familiar with current art movements, his style remained entirely his own. His legacy lives on through the Gershon Iskowitz Foundation and many works in public and private collections.

A Witness to the Holocaust

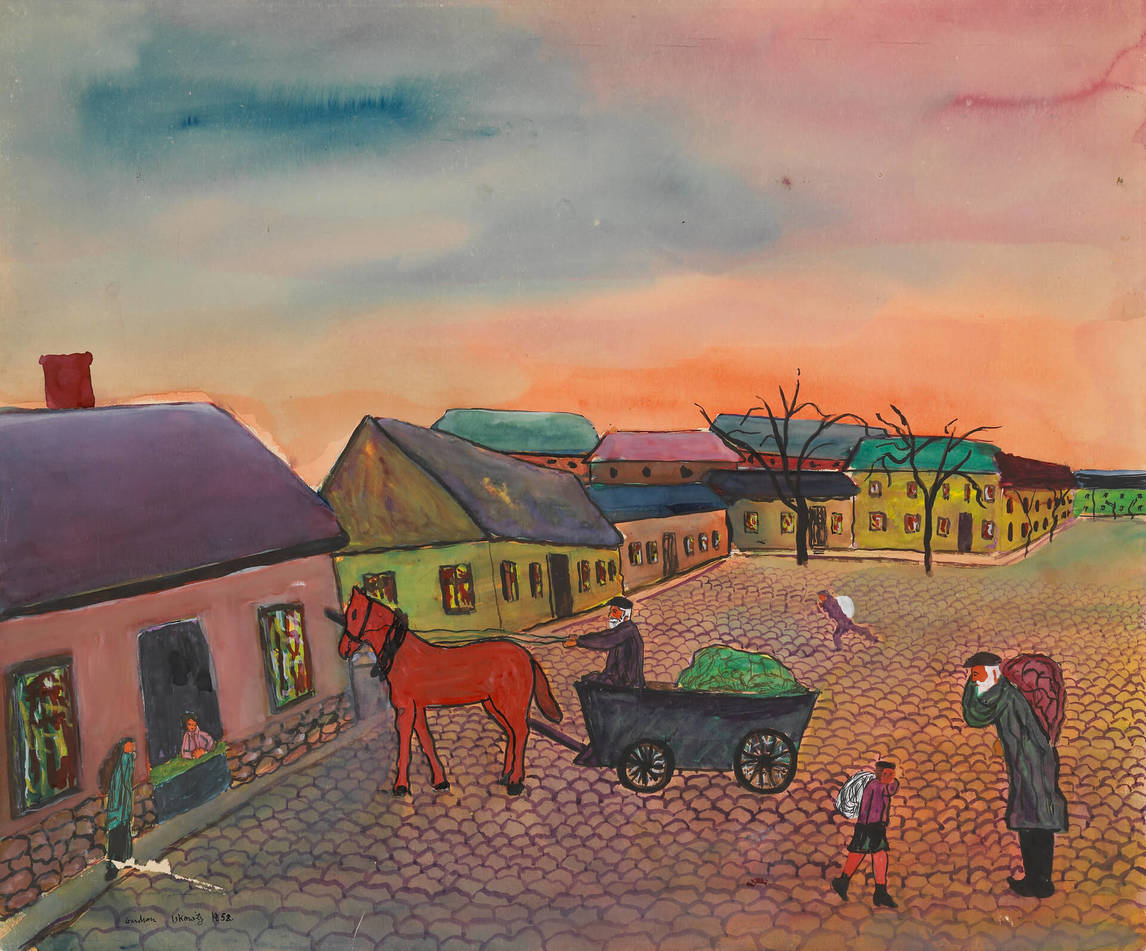

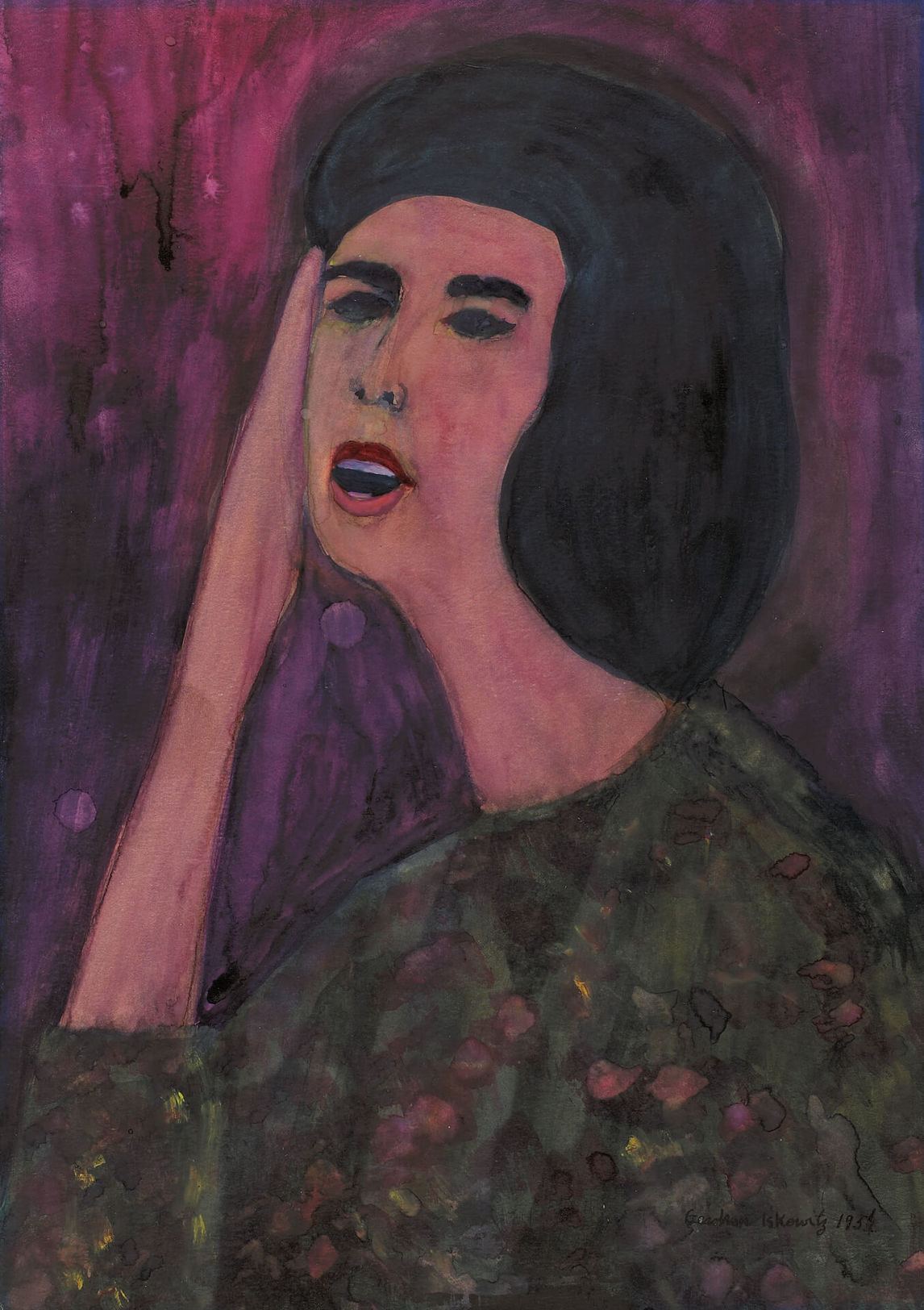

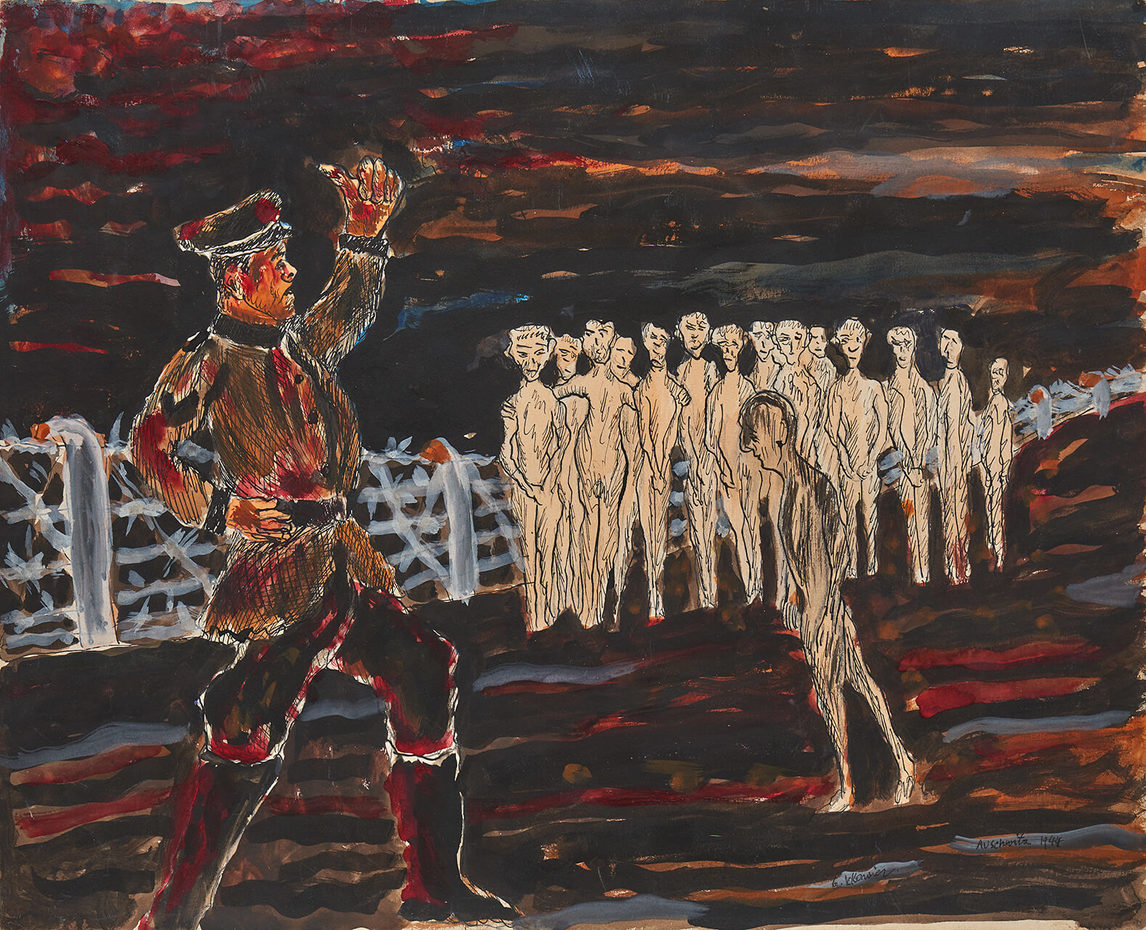

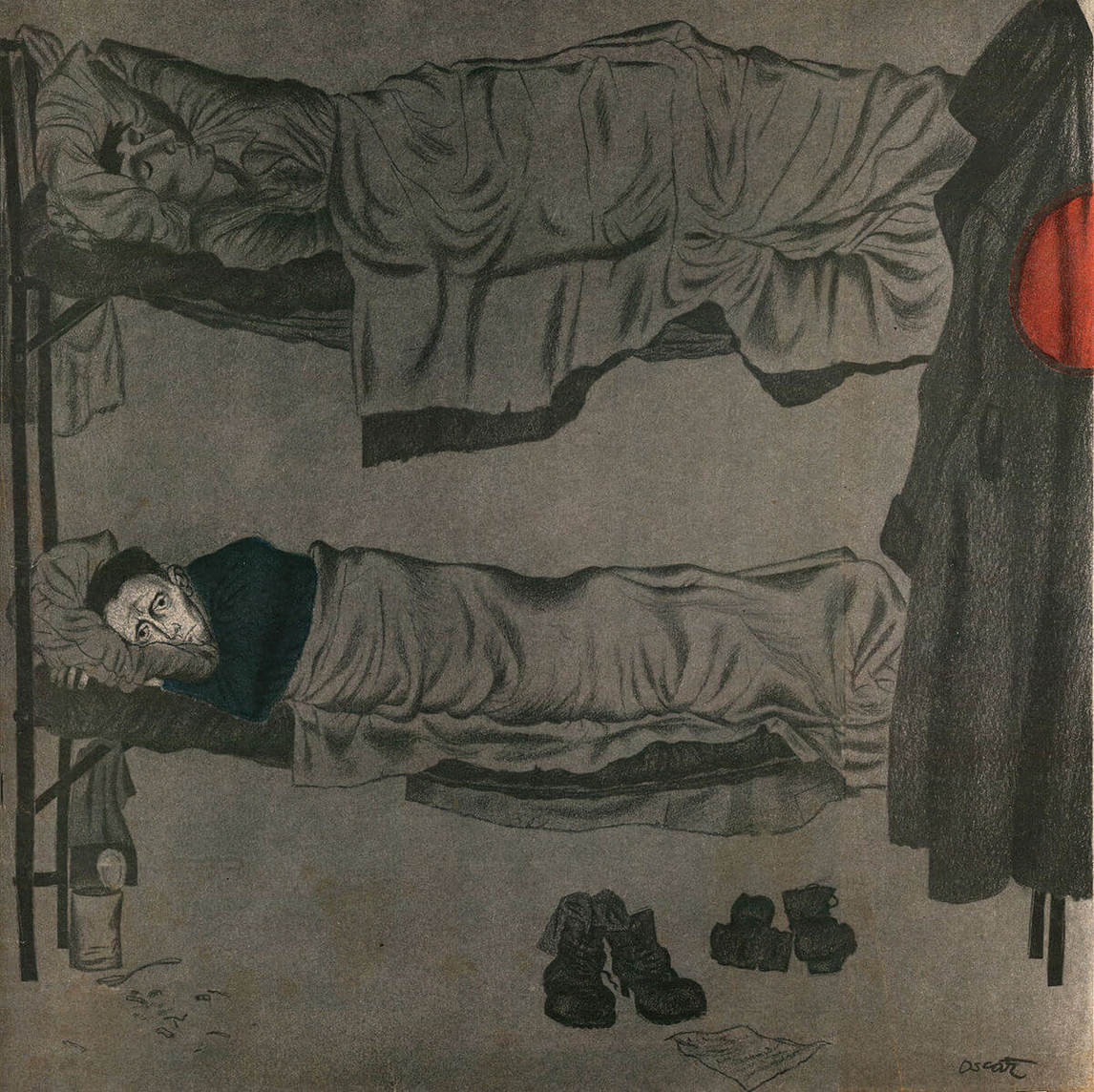

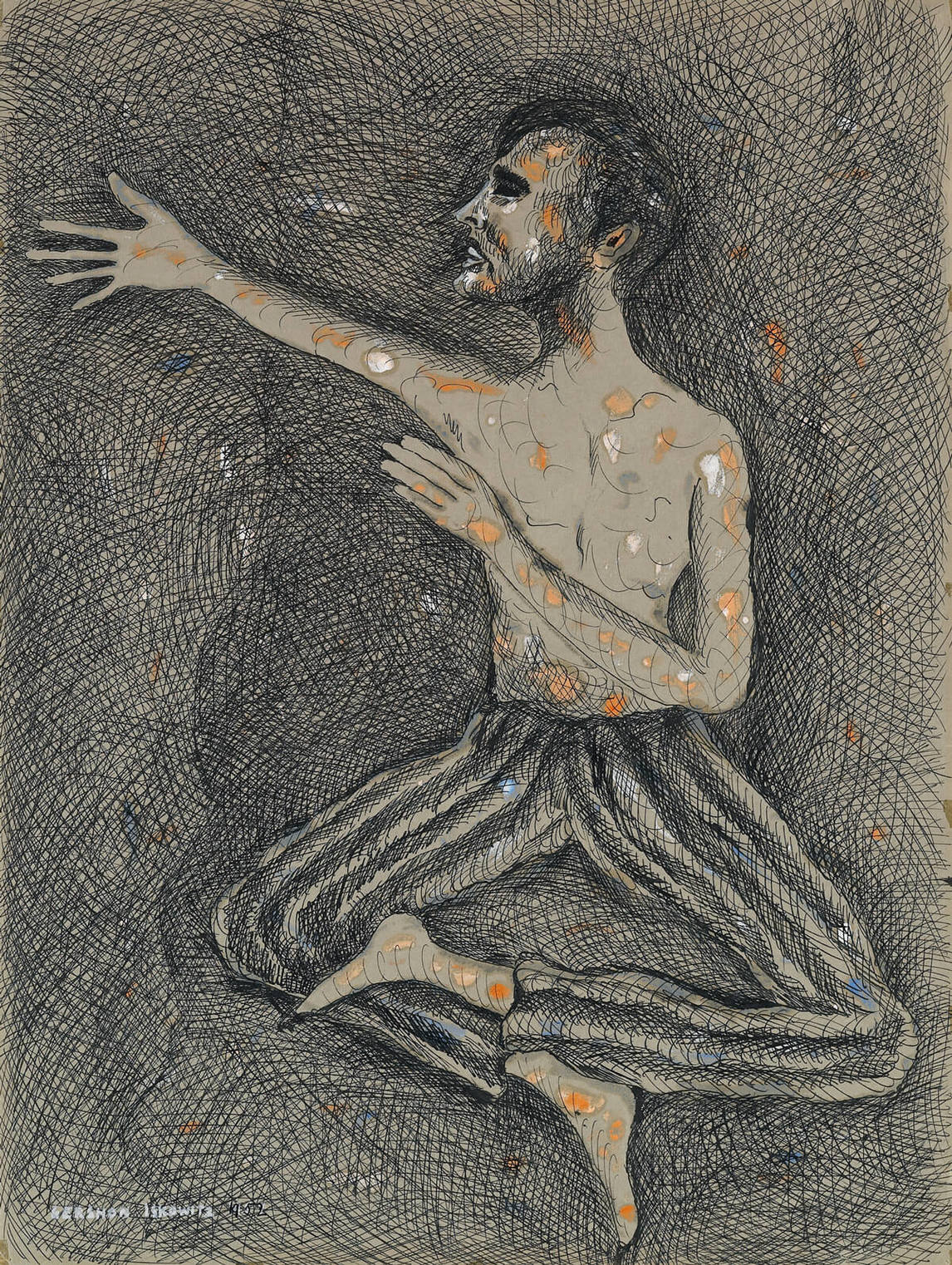

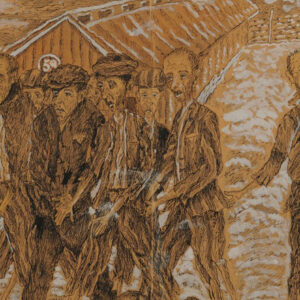

Iskowitz recounted that in the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps, he drew with scavenged materials to preserve his sanity and to forget about his hunger. Only three of his works from 1941 to 1945 still exist: Action, 1941, Buchenwald, 1944–45, and Condemned, c.1944–46. Following his liberation from Buchenwald in May 1945—beginning in 1947 and continuing after immigrating to Canada in 1948—Iskowitz made memory drawings, watercolours, and paintings. Earlier examples of these sketches depict impressions of the camps, such as Barracks, 1949, or of events, such as Escape, 1948. Other works, such as It Burns, c.1950–52, and Torah, 1951, depict the pogrom—the persecution of Polish Jews in his hometown of Kielce as the war began. But Iskowitz also created images that recalled everyday prewar life, such as Korban, c.1952, and Market, c.1952–54. These memory works are all rendered in a stark, naive style, and they document the destruction around him, the humanity of the survivors, and how he related to the experience as a survivor.

After the Allied victory, exposing and documenting the realities of the German camp system and the sheer number of its victims became part of the liberation effort: artists were commissioned to accompany the troops, and governments sent journalists, photographers, and newsreel crews to capture images that revealed the atrocities inflicted within these compounds. Canadian war artists such as Alex Colville (1920–2013) and Aba Bayefsky (1923–2001) documented the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp following its liberation in 1945, but they could give only an outside perspective, distanced by the fact that they witnessed the effects of the camps but not the reality of life inside them.

Iskowitz, in contrast, created his works from the perspective of a victim and a survivor, and his sketches are better compared with those by Otto Dix (1891–1969), who saw military action in the First World War, and Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), who lost a son in that conflict. The earliest and most significant “visual essays” in European art that depicted the horrors of war was Francisco Goya’s (1746–1828) suite of eighty-two engravings titled The Disasters of War, 1810–20, in which Goya recorded his response to the Peninsular War between France and Spain from 1808 to 1814.

Iskowitz was far from the only visual artist to document Holocaust experiences. The exhibition Art from the Holocaust, held at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, in 2016, displayed one hundred works from the art collection of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Israel. The images of Auschwitz, Theresienstadt, and Schwarzheide by Czech artist Alfred Kantor (1923–2003) were published in The Book of Alfred Kantor in 1971. Bill (Wilhelm) Spira (1913–2000), an Austrian cartoonist, and Jan Komski (1915–2002), one of the first prisoners of Auschwitz, both created small works of art capturing life and death in the concentration camps. It is difficult to make a general statement about the artists—those who did not survive and those who pursued art after the war—but their works bear testimony to the atrocities they endured. Yehuda Bacon (b.1929), as one example, survived Auschwitz as a young teenager (Iskowitz was a very young adult) and pursued art after the liberation. Initially, he too made memory and memorial works. In a 2005 interview, he stated:

I am somehow obliged because I survived to tell the story of the people who didn’t survive [and] I had to draw [and] say what I experienced in the hope that someone would learn from it. In Israel they have one day of commemoration of the Holocaust every year . . . but that is mainly for the other people who didn’t experience it. For us, the ones who survived, we live with it every day. We don’t have to have a special day.

Toronto film producer Harry Rasky (1928–2007) met and interviewed Iskowitz for his 1987 documentary Mend the World, his attempt, Rasky said, “to find meaning or perspective in the Holocaust, largely through the painted works of artists who lived through those days of human agony.” In Rasky’s interview transcript, Iskowitz is quoted as saying: “Even in the camps, I saw the sunset. It kept me alive . . . I got very inspired, not just for painting, I got very inspired with life.”

Iskowitz continued to depict his experiences after the war and through the early 1950s. Like Viktor Frankl, Elie Wiesel, and Primo Levi, whose published memories opened scholarly discussions about the relationships between trauma and memory and brought insight into victims’ personal experiences, Iskowitz exhibited his Holocaust work in group exhibitions in the 1950s; the traumatic period of his life in the Kielce Ghetto and in Auschwitz and Buchenwald were mentioned in relation to exhibitions in the early 1960s, but it was not until 1966 that they were reproduced in an article in the national weekly arts and culture magazine Saturday Night.

Iskowitz’s art dealing with his wartime experiences brings to mind what the French writer Charlotte Delbo, a survivor of Auschwitz, described as “deep memory,” a recollection of experiences of death of such magnitude that they seem to exist outside the life of the person who remembers them. Iskowitz’s portraits of his neighbour Miriam, c.1951–52, and his mother, as well as images of Kielce and the camps, draw on memory not to articulate a connection between life before the war and the losses that followed but to convey, in vivid colour, the artist’s emotional relationship to his past. Though from the mid-1950s on, Iskowitz, like Levi, sought to be known for subjects separate from the trauma he had experienced, art reviewers and members of the interested public never forgot his work as an artist of the Holocaust.

A Different Émigré Artist

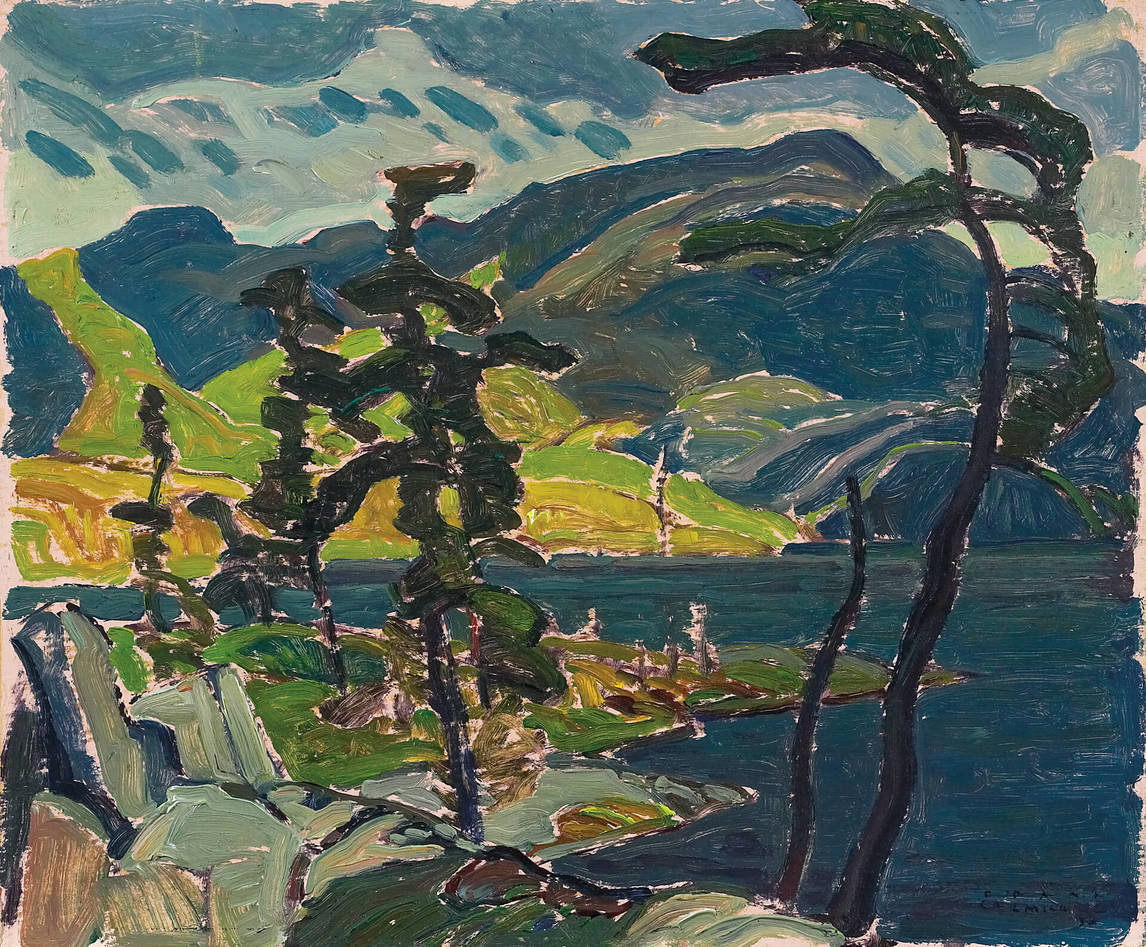

Gershon Iskowitz was very different from other émigré artists who came to Canada. Two who arrived before him in 1911–12, for example, the English artists Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) and F.H. Varley (1881–1969), emigrated voluntarily, attracted by the opportunity for skilled employment with the Toronto design company Grip Limited. For them and other British artists who settled in Toronto and Vancouver, Canada represented cultural continuity with the homes they had left, and they were immediately welcomed by local artists they met through work or social groups. They went on to play a key role in generating a national art movement through the Group of Seven. In the 1920s these painters explored ways to depict the natural landscape in raw colours and bold brush strokes, quite unlike the genteel, domesticated scenes earlier artists had preferred. Their inspiration, however, was rooted in the Western European modernist tradition, particularly in Scandinavia and the “Mystic North.”

In contrast, the immigrants to Canada in the years immediately following the Second World War were often driven by desperation: the countries they left in eastern and southern Europe were not only culturally different but had been severely damaged. Iskowitz’s experiences as an artist and as a new arrival to Canada have remarkable parallels with those of the painter and illustrator Oscar Cahén (1916–1956), though there are also important differences. Both men were young, Jewish, and embarking on an artistic career when the Nazis’ rise to power curtailed their ambitions. Iskowitz’s family was Polish, of limited means, and largely lacking connections to a network beyond their small town; Cahén’s background was prosperous, cosmopolitan, and connected, through his father’s work, to important intellectual communities across Europe. Iskowitz was imprisoned in concentration camps and a displaced persons camp before he immigrated to Canada; Cahén managed to escape to England on the eve of war, but one year later he was arrested, deported to Canada with other “enemy aliens,” and placed in an internment camp for two years.

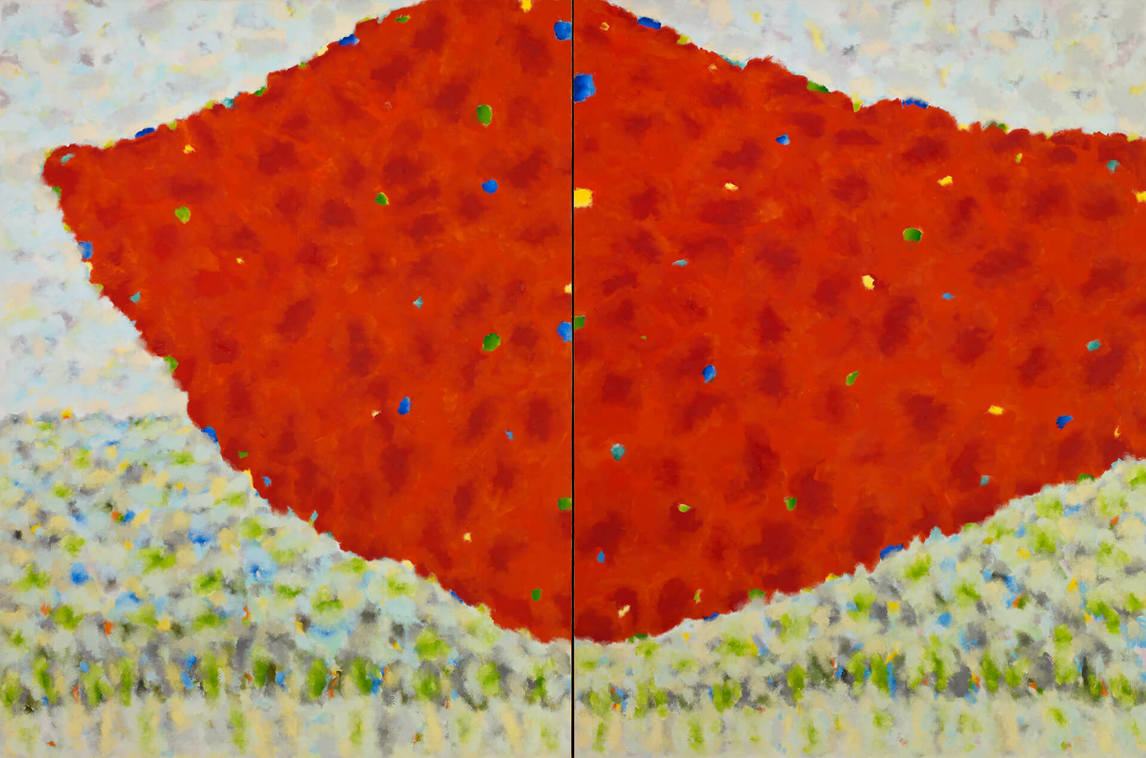

As Cahén and Iskowitz sought to establish themselves in the conservative Toronto art scene during the early 1950s, Cahén drew on his connections to European modernism to help guide the Painters Eleven with their experiments in abstraction. For example, Cahén’s Growing Form, 1953, takes cues from the postwar graphic compositions of British artist Graham Sutherland (1903–1980) and the vibrant colours that characterized works by CoBrA, a group of postwar artists that included prominent members such as Karel Appel (Dutch, 1921–2006) and Asger Jorn (Danish, 1914–1973) who were active in Europe. Iskowitz followed a different path, and there is no indication that new trends in art were of interest to him. He remained fiercely independent, moving from remembered images like Yzkor, 1952, through his vision of the Canadian landscape (as in Sunset, 1962), to large colour compositions such as Uplands H, 1972. None of his works fit neatly into any defined category—Canadian or otherwise.

In his private life, too, Iskowitz was different: he didn’t aspire to marry or have a family, and he disdained politics. “I don’t give a damn about society,” he said. “I just want to do my own work—to express my own feelings, my own way of thinking.” In the years immediately following his arrival, the conditions of art and culture in Canada began to change significantly. The Massey Commission on the development of the arts and sciences in Canada, begun in 1949, led to significant national cultural initiatives, including the formation of a Canada Council for the Arts to provide funding to artists and cultural organizations. Between 1967 and 1976, Iskowitz would receive six Canada Council grants for his work, establishing him as a Canadian painter in his own right.

A New Take on Landscape

Iskowitz found his place in Canadian art in the mid-1950s when he switched his subject matter from memories to landscapes, initially in the Parry Sound area north of Toronto. Paintings such as Parry Sound I, Street Scene Parry Sound, and Summer, all 1955, responded to the terrain in that area and bore some resemblance to works by Group of Seven artists—for example, Jack Pines, La Cloche, c.1935, by Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945). While a stylistic comparison can be made between Carmichael’s Spring, Cranberry Lake, 1932, and Iskowitz’s Parry Sound landscapes of the 1950s, Iskowitz’s painting was not a “project of the land.” Rather, it was a way out of his memories, allowing him to break with the past and begin a new life as an artist in Canada.

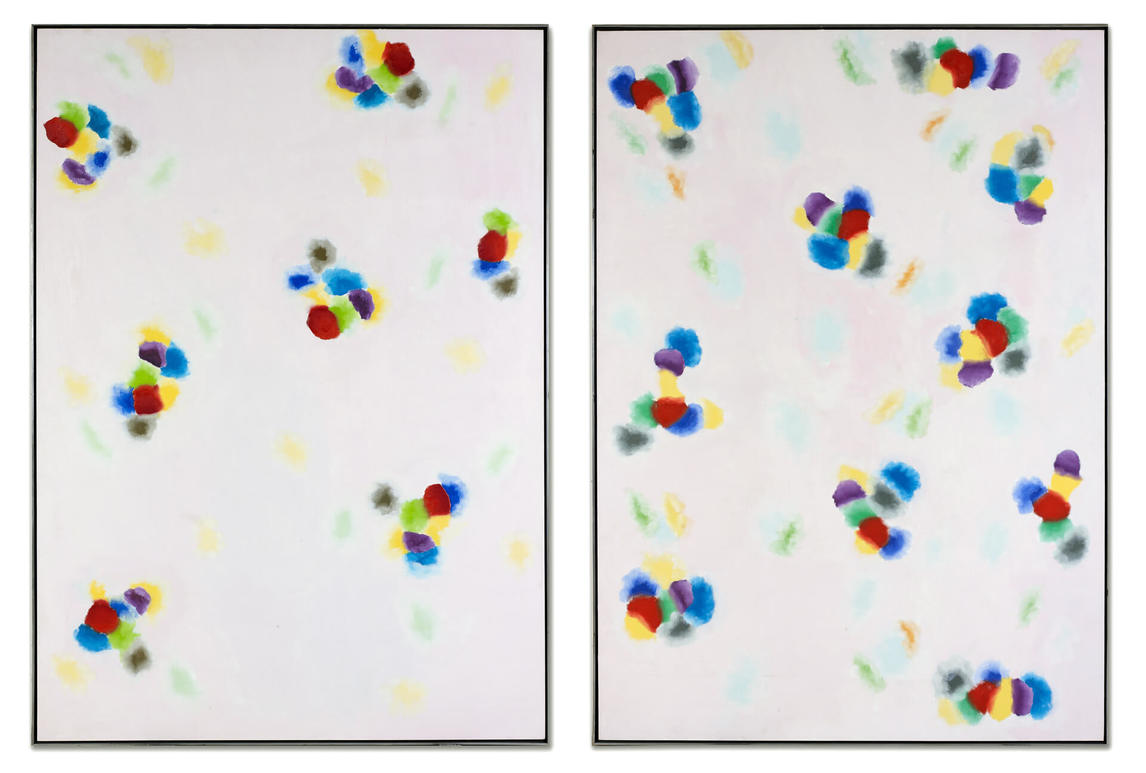

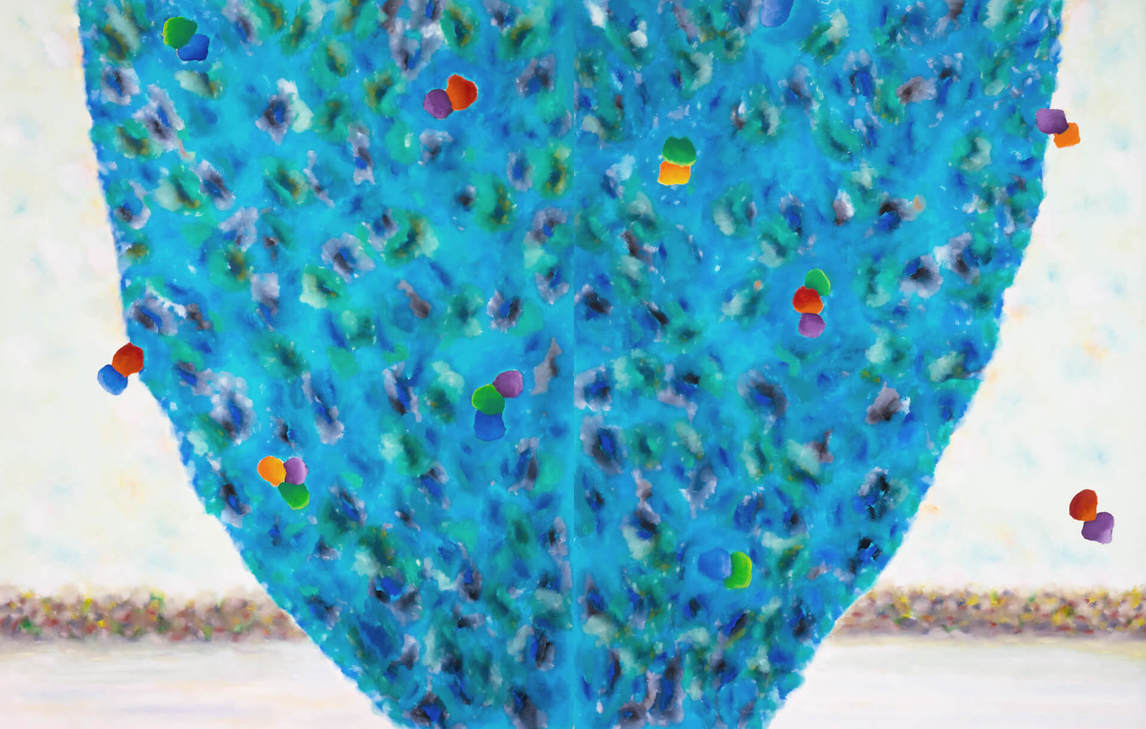

Around 1960 Iskowitz stopped painting literal landscape works and made a significant shift toward abstraction—as in Late Summer Evening, 1962, and Spring Reflections, 1963. While he maintained some pictorial elements in these beautifully coloured paintings, he dissolved the skies into glowing ribbons of light and deconstructed tree forms into brightly hued shapes that seem to explode outward from their trunks (Spring, 1962). He followed this artistic trajectory for the rest of his life. Iskowitz never explained the reason for this change, but perhaps, amid the freedom and independence he now enjoyed, he decided to pursue his own visual language and discover where it led.

By the late 1960s Iskowitz’s abstract pieces had become larger, with reduced elements—as in Autumn Landscape #2, 1967—and they fit with the progressive art being made at that time. Works by Painters Eleven members Jack Bush (1909–1977) and Harold Town (1924–1990), for instance, echoed the dominant trends in painting in the United States and Europe as well as in Canada. Since the 1950s abstraction had gained a wider reception in Toronto following exposure to works by Montreal’s Automatiste painters, led by Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), and the influence of important exhibitions such as Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America in 1951 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The influence of British modernists, including Henry Moore (1898–1986), and American Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), and Mark Rothko (1903–1970) was evident throughout this period.

In 1966 Harry Malcolmson was the first art critic to position Iskowitz in the Toronto art scene. In the text he wrote for Iskowitz’s solo exhibition at Gallery Moos, he grappled with questions of how Iskowitz’s abstract style fitted into the contemporary scene:

[Iskowitz’s] Canadianism comes out directly in [his] subjects [of] this country’s landscape, in particular the Ontario landscape [and] by now is a local painter in the best sense of the term. His personal vision and warmth at first foreign has passed into the community and after a period of time has become an integral part of it.

Canada remains a country in a close and vital relationship economically and psychologically with its landscape . . . In Iskowitz’s case his style has less in common with his Ontario contemporaries (such as Gordon Rayner and Harold Town) than with the modern generation of Quebec landscape painters . . . and in particular the flowing discontinuous surfaces of the 1960–63 [Jean] McEwen paintings.

Critic Kay Kritzwiser’s review of the 1966 exhibition described Iskowitz’s recent work as a “lyric abstraction” that he was now applying “to a countryside usually painted with Group of Seven eyes. Iskowitz,” she wrote, “makes us look at it anew.” In fact, as Malcolmson had astutely noted, Iskowitz had turned his view away from the horizon line, which defines a view of the land, and looked instead to the sky. He used colours from the land and applied them to the sky, and, because the sky has no shape or form, the works became abstract. Theodore Heinrich reiterated this point more than a decade later in an article related to Little Orange Painting II, 1974, and Seasons, 1974.

On the few occasions when Iskowitz talked to art critics about his art practice, he defended his independence and refused to be described by any of the common labels. In a 1975 interview with Merike Weiler, he said:

People say, oh, Gershon Iskowitz is an abstract artist. . . . But it’s a whole realistic world. It lives, moves . . . I see those things . . . the experience, out in the field, of looking up in the trees or in the sky, of looking down from the height of a helicopter. So what you do is try to make a composition of all those things, make some kind of reality: like the trees should belong to the sky, and the ground should belong to the trees, and the ground should belong to the sky. Everything has to be united.

Now, most of my work comes visually from memories, and the colour is also self-invented. I reflect things I’ve seen before up north, but you’ve got to look for a while to see the fact. If it becomes too obvious, it’s no use, it’s just a decoration. I think Season I and [Season] II reflected the Northern Lights, even without my knowing it. And the Uplands series . . . is a new evolution for me of flying shapes . . . the whole landscape. But it’s nothing to do with documentary. It’s above all that, it’s something you invent on your own.

Iskowitz was expressing something beyond the literal, just as instrumental music is formed with sound, tempo, and interval (the space between the sounds), not words. For him the sky was a universal view, one we can all experience regardless of where we live.

The Toronto Look

Group exhibitions, formed around themes—common style, subject matter, or what is new—are a useful way of tracking how an artist is written into a history of art. Although Iskowitz was selected for multiple group exhibitions with fellow Toronto artists, his positioning within the story of art in Toronto—and Canada—has remained apart.

Iskowitz began showing in Toronto just as commercial galleries began to multiply. Isaacs Gallery—the home for cutting-edge Canadian artists such as Gordon Rayner (1935–2010), Graham Coughtry (1931–1999), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), and Michael Snow (b.1928)—included him in a group show in 1957, and, three years later, Dorothy Cameron gave him his first solo exhibitions at her Here and Now Gallery. When he moved over to Gallery Moos in 1964, he was in international company: the Twentieth-Century Master group exhibitions that Walter Moos initiated in 1961 with artists such as Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Georges Braque (1882–1963), and Marc Chagall (1887–1985), and Canadian artists establishing international careers, such as Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002) and Sorel Etrog (1933–2014). From then on, Moos managed Iskowitz’s life and career very well.

After his frequent visits to Gallery Moos, Iskowitz often dropped into the other galleries in the Yorkville area: Mira Godard, Gallery One, Waddington & Shiell, and Jared Sable Gallery (later Sable-Castelli). He continued on to Isaacs and Carman Lamanna on Yonge Street and visited the David Mirvish Gallery on Markham Street, where his friend Daniel Solomon (b.1945) worked. There he would have seen large brilliantly coloured works by contemporary American Abstract Expressionist and colour-field painters including Hans Hofmann (1880–1966), Robert Motherwell (1915–1991), Frank Stella (b.1936), and Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011), along with the Canadian Jack Bush (1909–1977). Around his studio on Spadina, he became a father figure to a younger group of artists who were exploring a wide diversity of styles and were often represented by Isaacs. All these developments signalled a profound shift in the Toronto art scene—and Iskowitz kept abreast of it all.

The first significant group exhibition for which Iskowitz was selected presented a story of art in Toronto. In 1972 curator Dennis Reid organized Toronto Painting: 1953–1965 for the National Gallery of Canada. He placed Iskowitz in a section titled “The Toronto Look: 1960–1965,” though there was no common approach among these artists, which included both figurative and abstract work by Snow, Wieland, Coughtry, and Rayner. When the Art Gallery of Ontario mounted Toronto Painting of the Sixties in 1983, the one Iskowitz painting included, Summer Sound, 1965, had also been in the National Gallery exhibition.

In 1975–76 Iskowitz was selected for The Canadian Canvas, a multi-gallery partnership sponsored and circulated by Time Canada Ltd. Alvin Balkind, the curator of contemporary art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, chose the ten Ontario artists in the show. In his words, he “wanted to find very able, but little known (even unknown) artists and to mix them together with artists of known quality.” Senior abstract painter Jack Bush was included, along with younger abstract painters Ron Martin (b.1943) and David Bolduc (1945–2010) and the figurative painters William Kurelek (1927–1977) and Clark McDougall (1921–1980). Iskowitz was next selected for the Exhibition of Contemporary Paintings by Seven Canadian Painters from the Canada Council Art Bank, which was shown at the Art Gallery of Harbourfront, Toronto, and circulated to galleries in Paris, New Zealand, and Australia in 1976 and 1977. Other artists chosen were Claude Breeze (b.1938, the only figurative painter of the group), Paterson Ewen (1925–2002), Charles Gagnon (1934–2003), Ron Martin, John Meredith (1933–2000), and Guido Molinari (1933–2004).

None of these exhibitions laid claim to any stylistic commonality, but they offered an interim report of art in Canada in the moment. Iskowitz could be paired with no other artist: his “look” was unique.

Legacy

Mark Cheetham writes of Gershon Iskowitz: “Knowing an artist’s biography can be a trap for the ways we see and think about their work, because too often life’s events and art’s purposes do not align as perfectly as we might wish.” Iskowitz was a Holocaust survivor who worked through that trauma in his powerful and disturbing memory works from 1947 to 1954—for example, Through Life, c.1947; Yzkor, 1952; and Burning Synagogue, c.1952–53. But it was his later innovative abstract work—paintings such as Little Orange Painting II, 1974; the Lowlands series, 1969–70; and the Uplands series, 1969–72—that garnered him significant critical recognition.

Iskowitz added something different and individual to art in Canada, but he did so on his own terms. Through his rigorous discipline and lifelong determination to be an artist, he set an example of integrity rather than ambition—for which he was admired and respected by younger artists such as David Bolduc, Daniel Solomon, and John MacGregor (b.1944). He felt no need to subscribe to a “Canadian lens” or other forms of discreet assimilation. Iskowitz identified himself simply as an artist, and he may be best seen as a deterritorialized Polish Jew and Canadian, but never as a “hyphenated” Canadian.

Iskowitz’s legacy is twofold: his paintings and his foundation. An extensive body of work by him continues to be admired and exhibited in major public institutions—including the National Gallery of Canada, Art Gallery of Ontario, Winnipeg Art Gallery, and Vancouver Art Gallery—as well as in corporate and private collections across the country. But individual works by Iskowitz are not specifically iconic, a term that is best applied to pictorial art such as The West Wind, 1916–17, by Tom Thomson (1877–1917). Over time, Thomson’s lone tree and shoreline has become a stand-in for the Canadian wilderness. In contrast, the iconic for Iskowitz rests in the body of his work over time, a consistency of vision that stands for him.

Iskowitz appreciated the acclaim he received during his lifetime and the opportunities that came from living and working in Canada. That led to his second important legacy, the Gershon Iskowitz Prize. In 1982, the year of his retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario, he began working on plans for an independent charitable foundation that would provide financial support to Canadian artists of merit. “It’s very important to give something so the next generation can really believe in something,” he said. The Gershon Iskowitz Prize was first presented in 1986 and continues to be awarded annually. Winners have included General Idea (active 1969–1994) in 1988; Françoise Sullivan (b.1923) in 2008; Michael Snow in 2011; and Rebecca Belmore (b.1960) in 2015.

The Gershon Iskowitz Foundation was not mandated to promote Iskowitz’s oeuvre, but it is responsible for the artist’s inventory. On its tenth anniversary, in 1995, it gifted 148 works by Iskowitz—paintings, watercolours, drawings, printwork, and sketchbooks—to thirty-two public gallery collections across Canada. In 2006 it formed a partnership with the Art Gallery of Ontario, renaming the prize the Gershon Iskowitz Prize at the AGO and adding a solo exhibition of the recipient’s work at the gallery to the cash award.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements