Gershon Iskowitz (1919–1988) was born and grew up in Poland. The circumstances of his early life—the trauma of the Holocaust and the uncertainty of the immediate postwar period, followed by immigration and adaptation to Canada—provide the context within which we must try to understand and appreciate his work, for art and life were inseparable for Iskowitz. His early figurative images represent his tragic observed and remembered experiences. In his later luminous abstract works, he created his own vision of the world as he remade himself a new man in a different place.

Kielce to Buchenwald

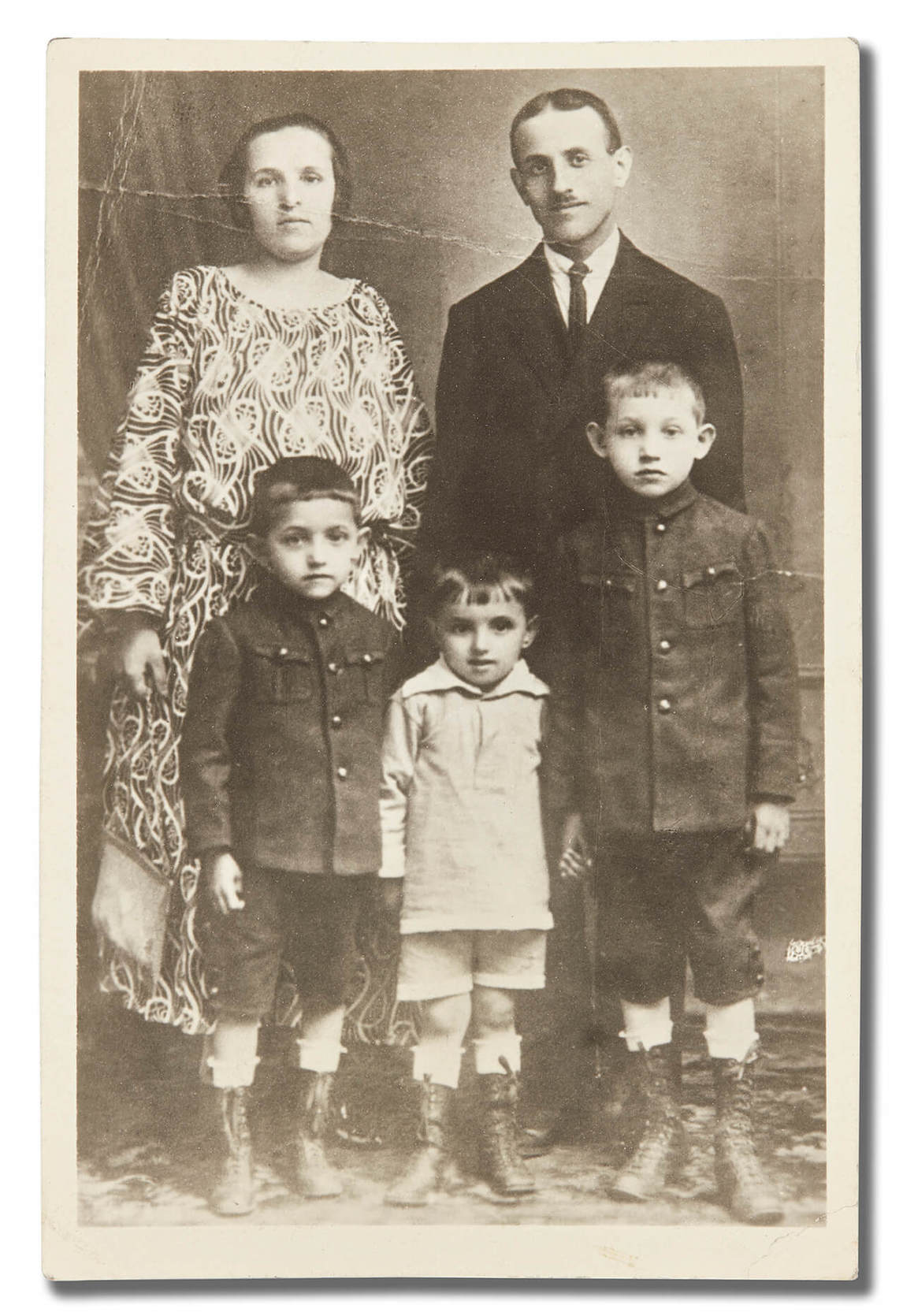

Gershon Iskowitz was born in Kielce—an ancient city in south-central Poland with a significant Jewish population of approximately 18,000 on the eve of the Second World War. His father was Szmul-Jankiel, generally referred to as Jankel; his mother was Zysla Lejwa. Gershon was the third of four children; he had two brothers, Itchen and Yosl, and a younger sister, Devorah. He was born on November 24, 1919.

The most comprehensive accounts of Iskowitz’s early life are found in two books written at the time of the Iskowitz retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1982: Adele Freedman, Gershon Iskowitz: Painter of Light, and David Burnett, Iskowitz. Both authors interviewed the artist extensively and recorded his stories. Unfortunately, there is a lack of basic documentation about him: Iskowitz kept only two key official records and a few photographs from a crucial period in his life, 1945–47, and he never saved any letters. New research has corrected many long-standing biographical errors, but his life story remains compelling—one of survival, renewal, and artistic achievement.

Jankel Iskowitz “made a modest living writing satirical pieces—poems, jokes, vignettes—for the weekly Yiddish language papers in Warsaw, Radom, and Kielce [but] did not take an active part in politics.” The family lived in the Jewish quarter, where most men were tradespeople or peddlers and the people were poor but self-sufficient, with their own schools, theatre, and social services. They lived in constant fear of opposition from the other townspeople—conflicts that erupted at times into pogroms. Hoping his son would become a rabbi, Jankel sent Gershon when he was only four to a nursery in Lublin sponsored by the Lublin Yeshiva, an important centre for the study of the Torah. But the boy rebelled against institutional life, so two years later he returned home and, over the next few years, attended a Polish school or was privately tutored. The family spoke Yiddish, but Gershon learned Hebrew, Polish, and some German before he turned ten. Early on he demonstrated an aptitude for drawing, and his father encouraged his talent by portioning off space in a front room of the house where he could sketch.

Gershon loved films, and the enterprising child made a deal with the owner of a local movie theatre to produce advertising posters in exchange for free tickets—and, later, a fee. He also drew good likenesses and caricatures of people within his social circle. Even as a young teenager, he knew he wanted to be an artist. He told how, when he was accepted by the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, he arranged to live with an uncle in the city and arrived there in August 1939. A few days later, the German Army invaded the city, and Iskowitz returned to Kielce.

The Nazi persecution of the country’s Jewish population began almost immediately. On March 31, 1941, the occupying forces established the Kielce Ghetto, a few square blocks surrounded by barbed-wire-topped walls and locked gates. The Iskowitz family and all the other Jews in the city were forced to live there. They were soon joined by Jews transported from elsewhere in Poland for “containment,” and by August 1942, more than 25,000 people were jammed into this squalid area. Hunger and typhoid ran rampant, and many people died.

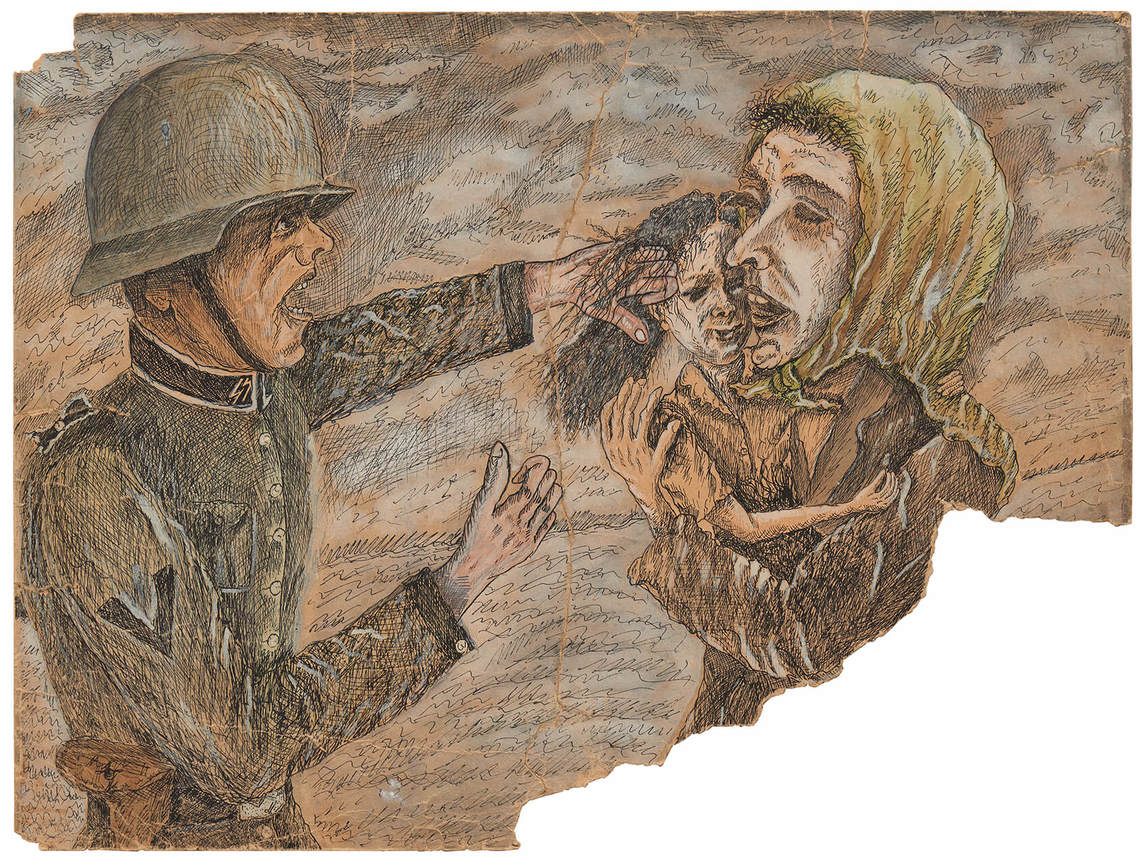

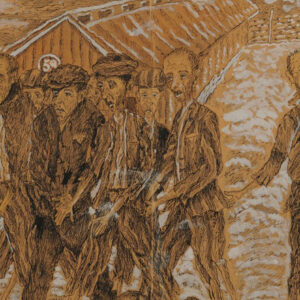

In his earliest surviving drawing, Action, 1941, Iskowitz records an incident he witnessed in the ghetto—a German soldier forcibly pulling a young girl from a woman’s arms. On August 20, 1942, the Nazi occupiers ordered the liquidation of the ghetto, and four days later, only 2,000 people remained. Many sick, elderly, and disabled inhabitants were rounded up and shot in the streets, but the others were sent on trains to the extermination camp at Treblinka, northeast of Warsaw. Iskowitz’s parents, brother Itchen, and sister all died at the camp.

Iskowitz and his brother Yosl were sent to the Henryków labour camp and, in early fall 1943, to Monowitz-Buna, a forced labour camp that was one of the three main sites of the Auschwitz concentration camp. There, Iskowitz’s left arm was tattooed with the prisoner number B-3124. In 1951, after he had settled in Toronto, Iskowitz made a drawing of his arm, recording the number. While imprisoned in Auschwitz, ill-clothed and half-starved, he worked fourteen-hour days in a cement factory and endured the naked “selection parades” carried out every two weeks by the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele. Whenever he could, he scavenged paper, ink, and other art materials and, alone at night, sketched the horrors around him and hid the drawings under loose boards in the barracks. Occasionally, guards asked him to make drawings for them and paid him with sausage or some bread.

In late 1944, as the Russian army was advancing westward into Germany, Iskowitz and many other Auschwitz prisoners were transferred in a 250-kilometre death march to the Buchenwald concentration camp. In the rush to depart, Iskowitz had no chance to retrieve his drawings. His brother Yosl was not among the marchers, and Iskowitz presumed he had died in the camp. When he arrived at Buchenwald, he played sick: he understood the camp mentality—a bullet would not be wasted on someone who was going to die of “natural causes.”

Later in life, Iskowitz spoke of the horrors and his state of mind during his time in Buchenwald, of why he continued to make drawings there: “I did it for myself . . . I needed it for my sanity, to forget about my hunger.” He used materials he could scavenge in the camps, and as he described, he came across paper and cakes of watercolour on a work detail. Only two sketches survived his time in Buchenwald, Condemned, c.1944–46, and Buchenwald, 1944–45.

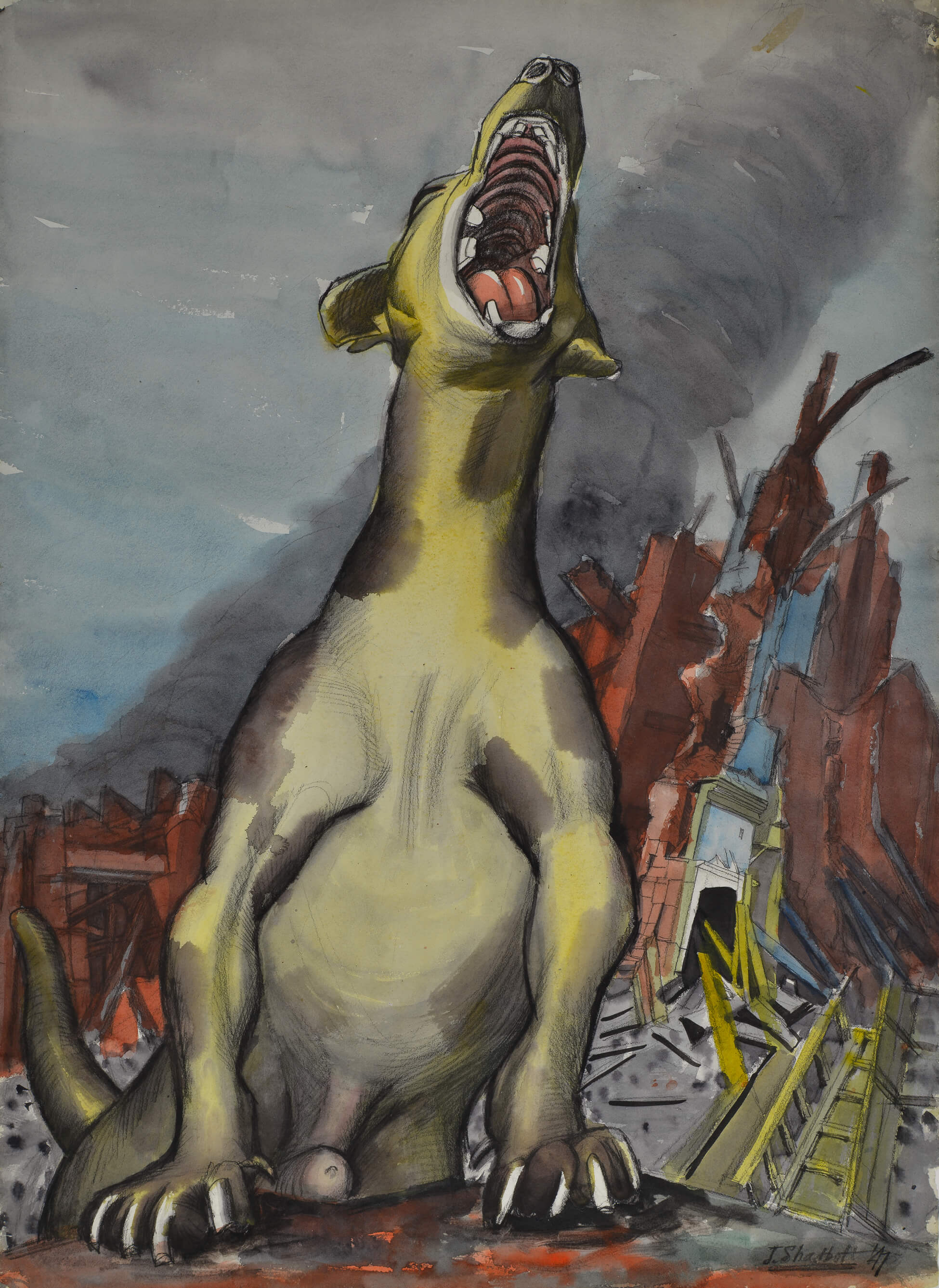

Iskowitz was not alone in documenting the camps. Among Holocaust survivors, Constance Naubert-Riser writes, “were artists who had the strength to bear witness to this sinister enterprise. The more intimate nature of [such works] takes us to a real and interiorized proximity to death.” Their work stands in contrast to paintings by official war artists who could depict the camps only “from the outside.” Canadian artists such as Alex Colville (1920–2013), Aba Bayefsky (1923–2001), and Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) documented prisoners in the weeks after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen and the destruction of war.

Buchenwald had been constructed in 1937 as a forced labour camp with sub-camps and as a centre for “medical experiments” and extermination by Nazi doctors. The Nazi Schutzstaffel had imprisoned some 250,000 people there between 1937 and 1945, and more than 55,000 internees had died. Fearing that the Germans were about to dynamite the camp, Iskowitz made one desperate escape attempt. As he scrambled over the surrounding fence, he was shot in the leg and fell to the ground, breaking his hip. He was left for dead by his pursuers, but his friends brought him back to the barracks, where he remained until the Americans arrived two weeks later. The injury left Iskowitz with a pronounced limp for the rest of his life.

In the end, there were approximately 21,000 survivors when Buchenwald was liberated by a division of the U.S. Third Army on April 11, 1945. Gershon Iskowitz was among them.

Feldafing and Munich

After his liberation, Iskowitz was taken first to a hospital and then to a sanatorium, with suspected tuberculosis. On October 31, 1945, he was registered at the Feldafing Displaced Persons Camp south of Munich, which had been established by the United States Army exclusively for liberated Jewish concentration camp prisoners. Although the camp was initially an emergency measure, by 1946 there were 4,000 inhabitants; it was a self-sustaining community with educational and religious life, a rabbinical council, and vocational training, including making coats from dyed U.S. Army blankets. Iskowitz most likely remained at Feldafing until he immigrated to Canada in September 1948. The camp finally closed in March 1953.

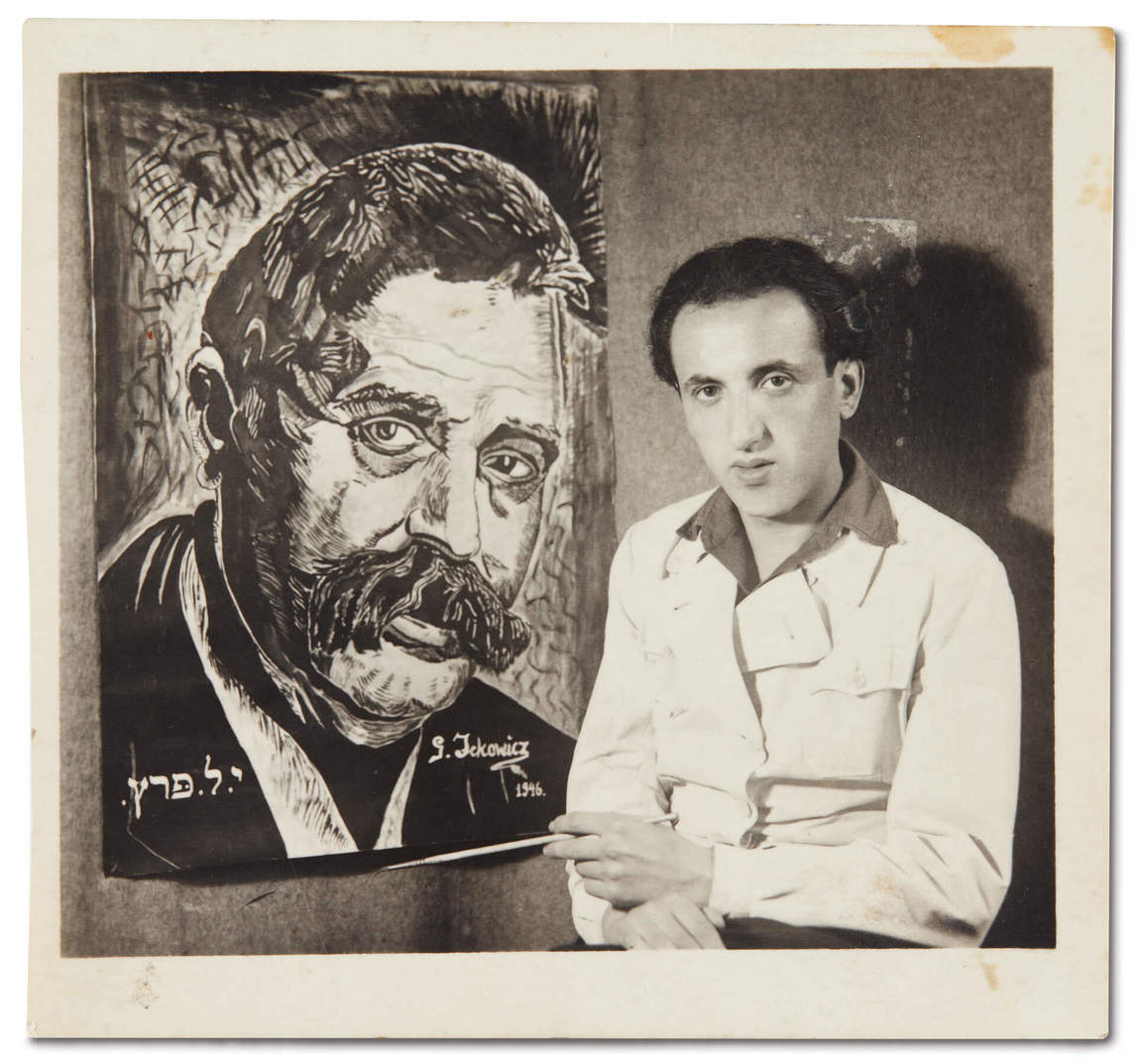

In Feldafing, Iskowitz began to paint again. A photograph shows him posed with his portrait of the Polish Jewish author and playwright Isaac Leib Peretz (1852–1915), which he had painted from a photograph. He also continued to draw—photographs of self-portraits exist as well as memory drawings of life in the Kielce Jewish quarter and scenes from the concentration camps, including Escape, 1948, and Barracks, 1949. Many of these pieces were painted in bold, bright colours, and they can all be confidently dated to his time at Feldafing.

Iskowitz said he was accepted as a student at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich, and over the next eighteen months travelled there by train every day. His name does not appear in the official records, but at this time the academy was housed in an old castle while its original building was being restored. New students were not registered but advised to do a year of independent work or be a “guest” of the academy. In all probability, Iskowitz audited classes.

Iskowitz described how, during these months in Munich, he received advice about form and composition from the Austrian Expressionist artist Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980)—encouragement that was very important to him. In June 1946 Kokoschka was a candidate for a professor’s position at the Munich Academy, and it’s possible that he came to the city at that time. There are, however, no records of a visit in either the Munich Academy files or the Kokoschka Archives. Kokoschka travelled to the United States in 1947 and lived for much of that year in Switzerland. His first recorded postwar trip to Munich was not until September 1950, for the opening of his exhibition in the Haus der Kunst. If there was a meeting between Iskowitz and Kokoschka in Munich, it was almost certainly by chance and informal. Nonetheless, it is clear that Kokoschka’s work was important to Iskowitz and offered him an inspirational model—a “meeting of minds.”

Other stories Iskowitz told of his time at Feldafing relate to surreptitious trips to Paris and to Modena, Italy, for group exhibitions that included some of his war and memory sketches. He indicated that he visited galleries in Munich, where he may have seen works by Edvard Munch (1863–1944), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Kokoschka, who were included in 1947 exhibitions. He also said that he painted sets for the Bavarian State Opera in Munich “part-time”—Aida, La Bohème, Lucia di Lammermoor—and used the money to buy art supplies. As with so much from this time, none of these accounts can be verified.

Coming to Canada

In the turmoil following the war, the victorious powers had to alleviate devastating shortages of food, fuel, and housing for millions of displaced Europeans even as they tried to disarm Germany, reopen schools, and restore some semblance of a functioning democracy. Iskowitz was one of an estimated 250,000 Jewish refugees who passed through the displaced persons camps. A number of relief organizations worked with diplomatic missions and the Allied military in assisting Holocaust survivors. Many had no home to return to, and emigration was the only option. Iskowitz had lost all his family members and, moreover, he would have heard about the continuing anti-Semitism in Poland and yet another ugly pogrom in Kielce: “The Feldafing court helped investigate the perpetrators of the Kielce pogrom of 1946 and publicized information about the Nazi murderers of Lithuanian Jews who were thought to have been in the vicinity.” He decided to leave Europe and build a new life in North America.

Within a month, Iskowitz’s emigration process was underway. His maternal uncle, Benjamin Levy, lived in Toronto, and he sponsored Iskowitz’s application. He deposited $162 with the United Service for New Americans to cover the cost of Iskowitz’s transportation to the United States, where the Kielce Landsmannschaft (a Jewish philanthropic organization) would take responsibility for him. He offered to provide funds for his nephew until he became self-supporting. Obstacles arose: on March 28, 1947, the American consul informed Iskowitz he would have to “wait two to three years under the Polish Quota”; and the Jewish Immigrant Aid Services in Canada (JIAS) told Levy they could not file an application because nephews older than eighteen years of age were inadmissible to Canada. On April 12, 1948, a letter from the JIAS to the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society of Chicago noted that Iskowitz did not qualify for entry to Canada and that entry to the United States might take years. Levy requested and received a full refund of his deposit.

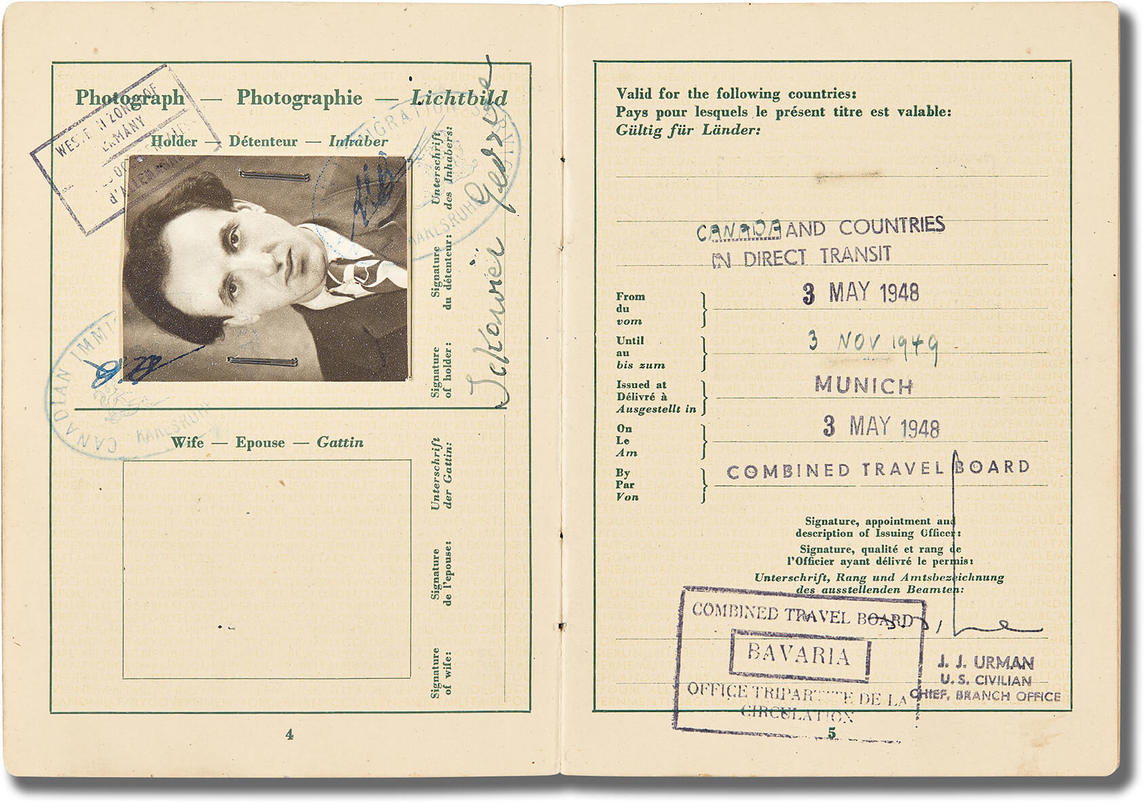

Despite these setbacks, on May 3, 1948, Iskowitz received a temporary travel document, issued by the Military Government for Germany to stateless people in lieu of passports, which authorized voyage to “Canada and Countries in Direct Transit.” On it are two “Canadian Immigrant Visa” stamps and one from the “Dept. of National Health Welfare Canada, London,” dated May 16, 1948. Iskowitz boarded the USAT General Stuart Heintzelman at Bremerhaven in northwestern Germany on September 17, 1948, and on September 28, 1948, he arrived, via Brooklyn, New York, at Pier 21 in Halifax.

A New Beginning

Iskowitz travelled by train from Halifax to Toronto, where Benjamin Levy and other members of his extended family met him at Union Station. They were all strangers to him, but one of his aunts invited him to stay with her at 218 Rusholme Road until he got settled. He knew no English and, initially, he hated Toronto. Over the next few years, Iskowitz moved many times, mostly from one boarding house to another. He picked up casual jobs whenever he could and visited the few local galleries—Roberts, Laing, Hart House, and Douglas Duncan’s Picture Loan Society. He thought the work he saw there “provincial.”

On the voyage to Canada, Iskowitz had met Yehuda Podeswa (1924 or 1926–2012) (also known as Julius and Yidel), who had been liberated from Kaufering, one of the Dachau concentration camp sites. Podeswa had also been born in Poland and aspired to be an artist, as his father had been. During his internment, he had created memory paintings, including Early Times in the War (Burning Synagogue), 1945, and later he studied briefly at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto. Iskowitz and Podeswa became friends and visited each other’s “studios,” and in 1954 Iskowitz painted his portrait. Through Podeswa and others, Iskowitz began to meet students at the art college and make some artist friends. In the 1950s he attended informal life-drawing classes at the Artists’ Workshop and produced untitled life drawings and street sketches, which were probably never exhibited.

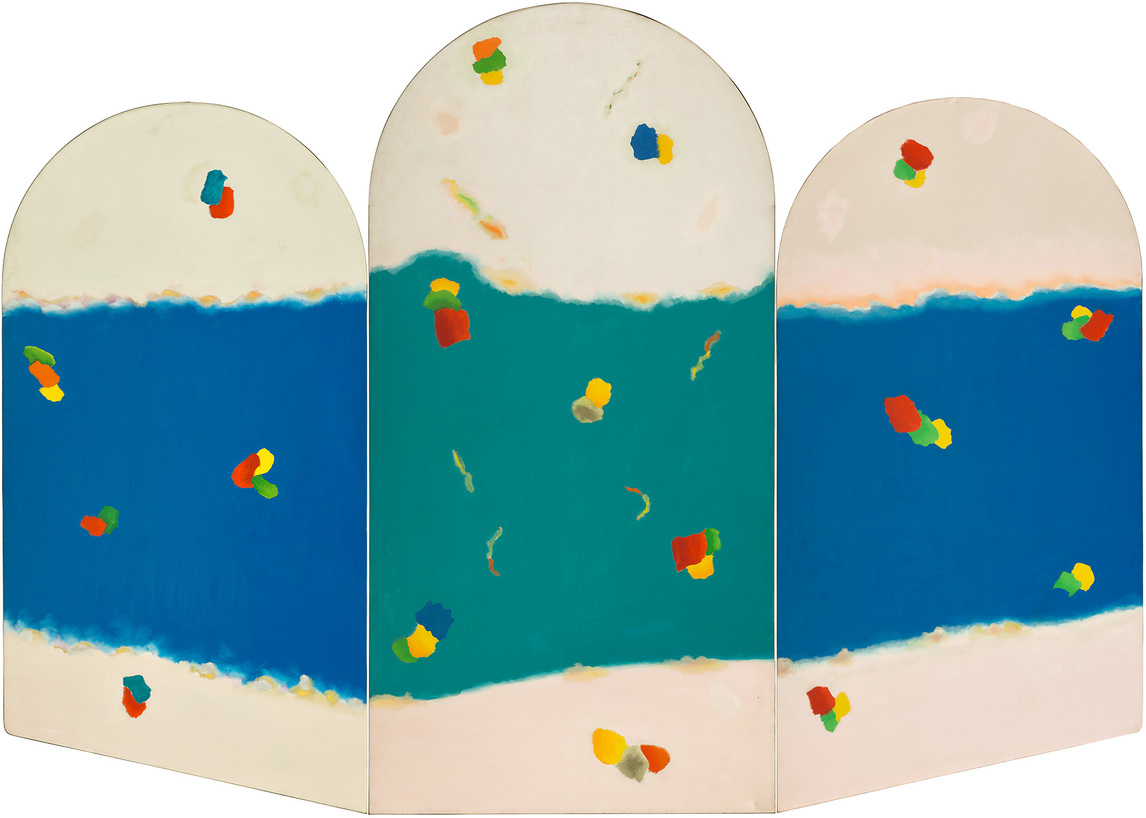

In due course he received a few portrait commissions—a 1954 painting of Muriel Hirst is one possible example—and in 1953 was hired to teach an evening art class at Holy Blossom Temple, a reform synagogue on Bathurst Street. The Toronto Jewish community followed Iskowitz’s career closely, covering his exhibitions in the Canadian Jewish News and other publications. He was not openly religious, although he always maintained social connections with Jewish friends. It is most likely that the arched tops of his Uplands three-panelled painting, 1969–70, later repeated in the Northern Lights Septets, 1984–86, are a visual allusion to his early religious instruction, synagogue experiences, and to the popularized representation of Hebrew tablets. Nonetheless, Iskowitz never spoke of his reasons for shaping these paintings.

From 1948 until 1954, Iskowitz continued to create works from memory as he had in Munich—recollections of life in Poland, such as Yzkor, 1952, and Korban, c.1952; the Kielce Ghetto, such as Torah, 1951; and the Auschwitz and Buchenwald camps, such as Escape, 1948. These were done in gouache or bodycolour on board and paper. He also branched out into portraits and flower still-life works, as in Untitled Flowers in Vase, n.d. His friends drove him on sketching excursions to Markham (then on the rural outskirts northeast of Toronto), and he sometimes went there by bus as well. In 1952 he made his first “pure” landscapes with felt marker—untitled works intended to express his experience and observations of the natural world in a gestural style.

In 1954 Iskowitz appeared in his first recorded exhibition in Canada—the annual show organized by the Canadian Society of Graphic Art at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). He submitted two ink and watercolour works, Barracks, 1949, and Buchenwald, 1944–45, and listed them both at $300 each, by far the highest price of any work in the exhibition. Two well-known members of Painters Eleven were also included in the show, Oscar Cahén (1916–1956) with a wash and crayon work priced at $75, and Harold Town (1924–1990) with two “print drawings” for $35 each. Iskowitz continued to show regularly with the Society of Graphic Art until 1963.

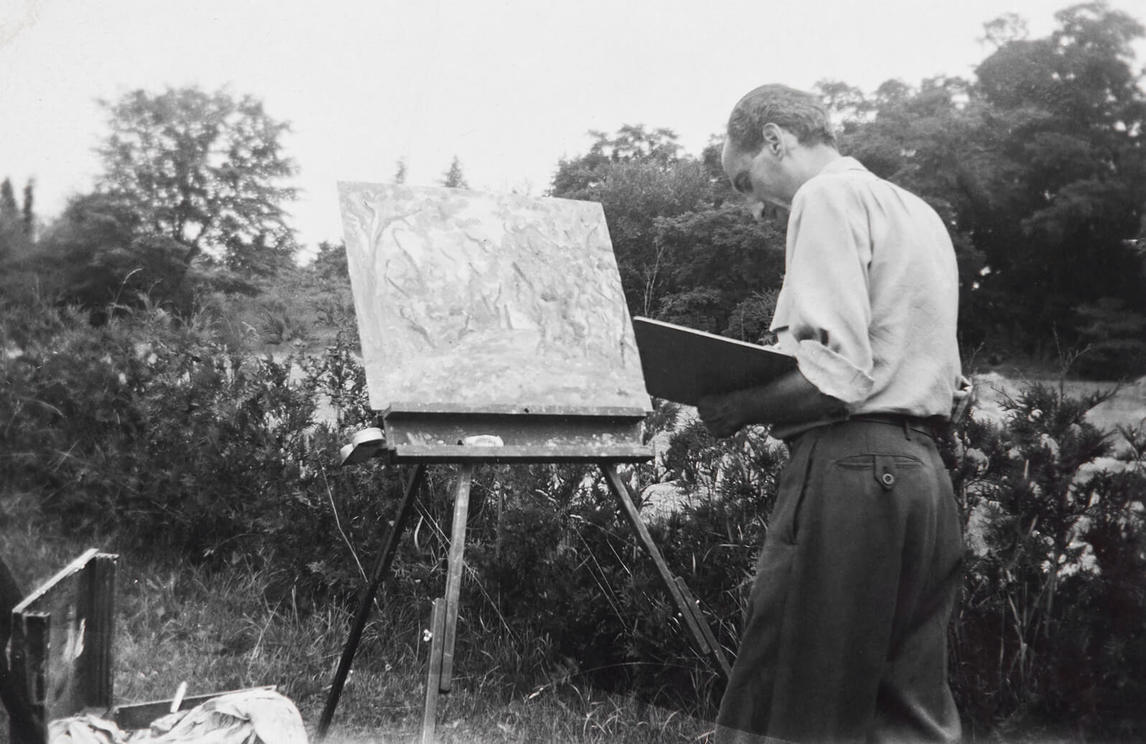

Around this time Iskowitz became friends with Eric Freifeld (1919–1984) and William Coryell (n.d.), both graduates of the Ontario College of Art, and he painted Freifeld’s portrait in oil (1955). In 1954 Coryell took Iskowitz to the “summer school for painting” at McKellar, northwest of Parry Sound, run by Bert Weir (1925–2018). There artists mentored the students in exchange for food and lodging, and in these welcoming, congenial surroundings, Iskowitz blossomed. He returned every year until 1965 to his “Canadian family.” His art also progressed, from literal depictions of landscapes to increasingly abstract compositions of colour and light as he looked through the trees to the sky or studied the lake below from a cliff (Sunset, 1962). His trees deconstructed into brightly coloured shapes, his skies into strokes of sun and cloud, sometimes with the suggestion of flames or a figure lurking within. The first of his works to enter public galleries were both Parry Sound abstracts from 1965. Parry Sound Variation XIV was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada, and Summer Sound by the Art Gallery of Ontario, both in 1966.

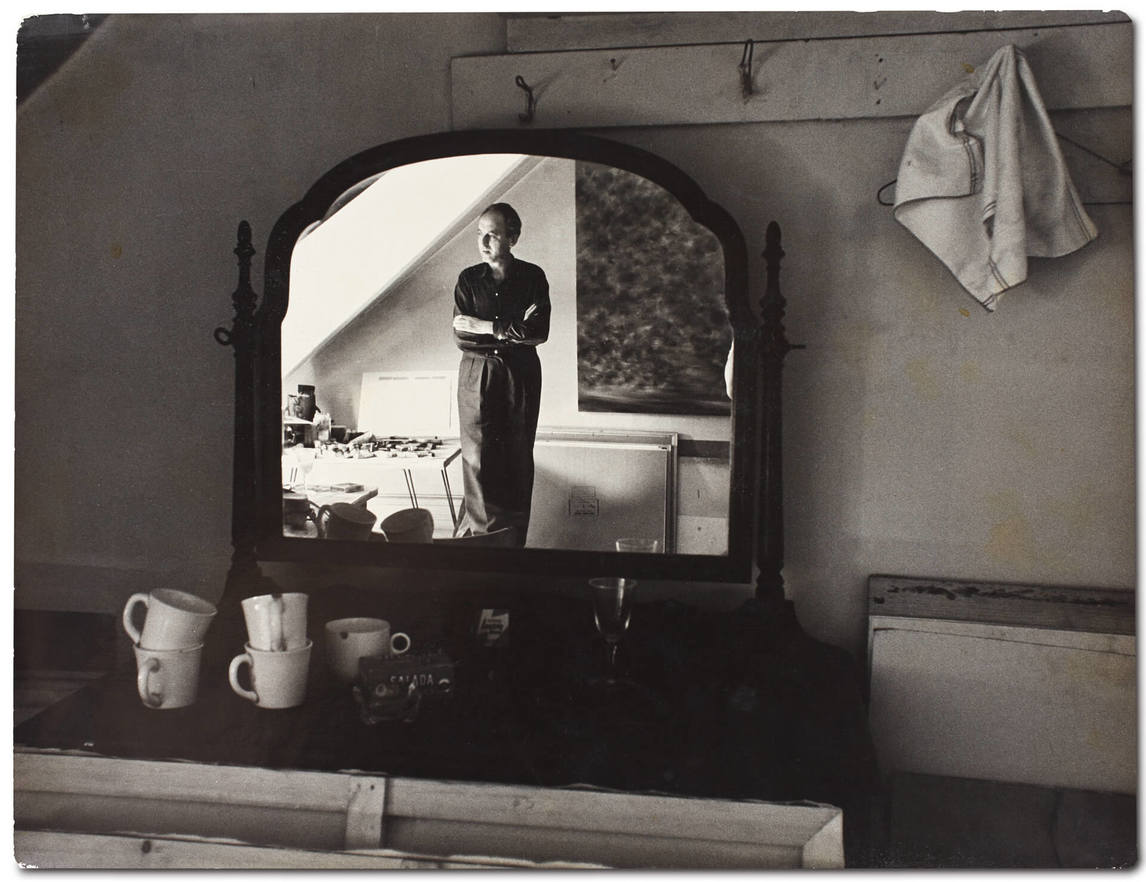

In 1962, Iskowitz felt secure enough in Canada to move into the first independent living space he ever had—a two-room studio he rented on the third floor at 435a Spadina Avenue. He was forty-one years old, and he finally had the space in which he could paint large canvases and set his own schedule. He stayed there for the next twenty years.

A Toronto Artist

The Toronto gallery scene in the early 1950s was relatively small yet lively, with few opportunities for emerging artists to exhibit and a minuscule market for the work of contemporary Toronto artists. But that was about to change, with the opening of new avant-garde spaces such as Isaacs Gallery and the formation of Painters Eleven—an ambitious group of artists determined to succeed. Within a few years, art and artists became fashionable as people flocked to gallery openings and began to buy art.

The short-lived Hayter Gallery gave Iskowitz his first solo exhibition, from September 14 to 28, 1957, but there is no record of what was shown. Two years later, Dorothy Cameron (1924–1999) included him in the opening exhibition of her Here and Now Gallery on Cumberland Street, which also featured work by Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) and Alexandra Luke (1901–1967). Iskowitz felt that Canada was now his home, and he became a Canadian citizen on February 13, 1959.

Although there is no definitive date for Iskowitz’s turn to non-representational art—no works dated between 1956 and 1959 have been identified—by the start of the 1960s, his work had become abstract. In March 1960 he had his first solo exhibition with Cameron, and the second in September 1961. There are no checklists for these shows, and newspaper reviews mention only recent works; one undated image is titled Sunset. However, Cameron was deeply moved by his memory paintings, and a press release from the 1960 exhibition mentions one Holocaust work. “People were glad to see [Iskowitz] really could paint,” she recalled. “Because he wanted to be an artist so much, they were always afraid it was just a dream of his.”

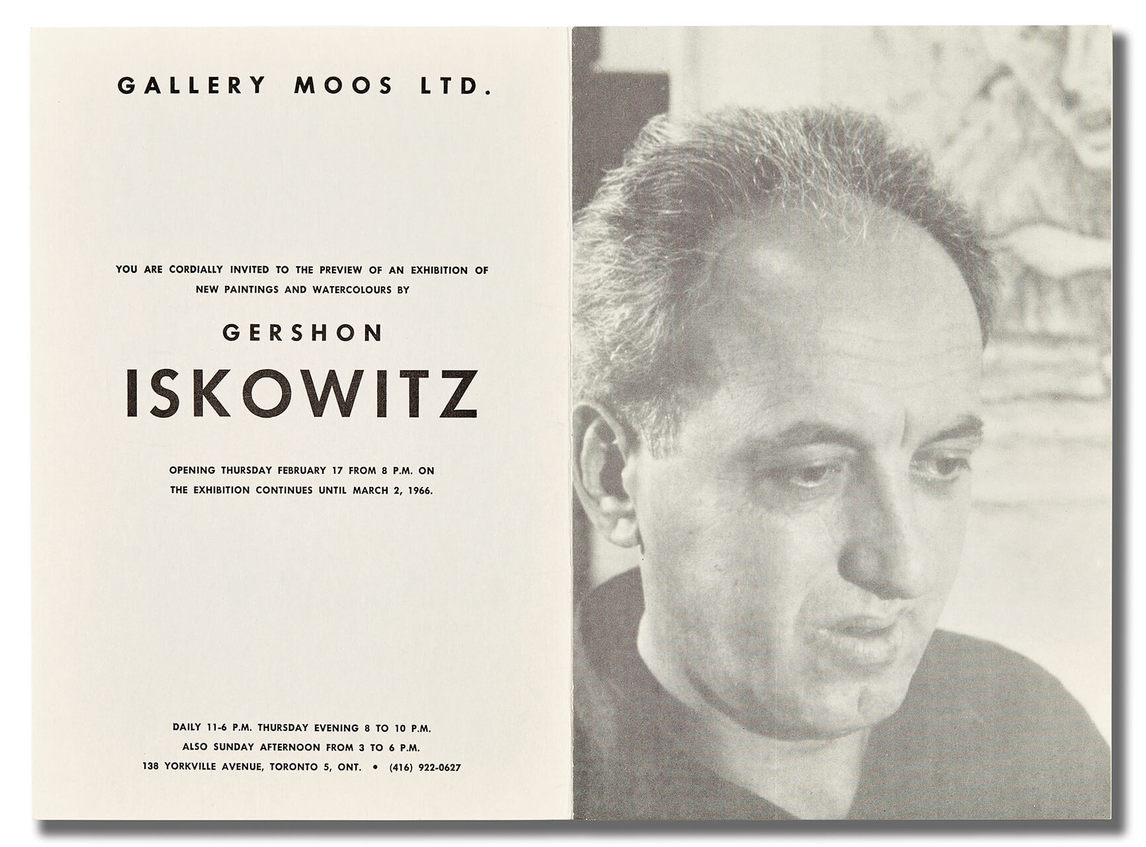

Iskowitz’s final solo exhibition with Cameron was in October 1963. “There was a joy and serenity in everything he was doing,” she said. “He’d taken the Canadian landscape and turned it into something we never saw in [it].” The reviews in all the newspapers were equally laudatory. Shortly thereafter, she introduced Iskowitz to Walter Moos (1926–2013), a well-connected German-born Jewish émigré who had opened a Toronto gallery in 1959. Cameron closed her gallery in October 1965 but continued to be a friend and supporter of Iskowitz throughout his lifetime.

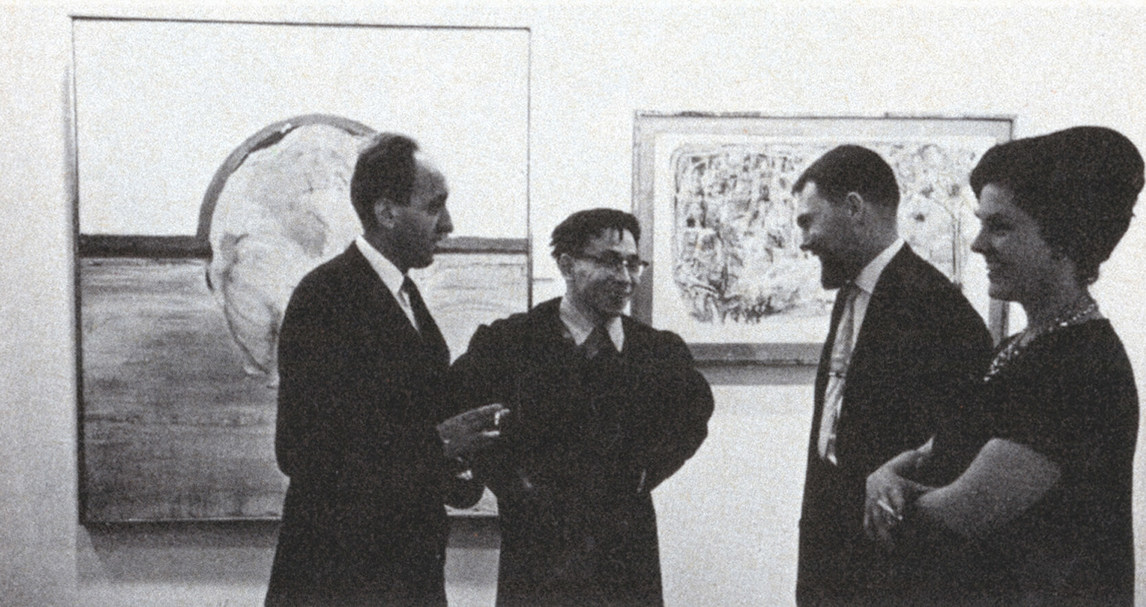

Iskowitz’s first exhibition at Gallery Moos was in October 1964. He and Walter Moos developed an active professional relationship that lasted for the next twenty-four years as Moos managed all the details of Iskowitz’s career and finances. Although six years younger, Moos became an “uncle” to the artist and remained committed to his work and legacy all through Iskowitz’s life.

In short order, an active market had developed for Iskowitz’s luminous abstract landscapes. He had regular, often annual, solo exhibitions at Gallery Moos from 1964 through to the 1980s, which garnered positive critical attention and solid sales. Public galleries also began to take notice: in 1966 the University of Waterloo gave him a solo show, followed by the Cedarbrae branch of the Toronto Public Library. Subsequent solo exhibitions were mounted at Hart House Gallery, University of Toronto, in 1973 (remounted at Rodman Hall Art Centre, St. Catharines, in 1973); the Glenbow-Alberta Institute in 1975; and the Owens Art Gallery in Sackville, New Brunswick, in 1976 (remounted at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in 1977).

Published biographical accounts indicate that, in the late 1960s, Iskowitz taught at the New School of Art in Toronto. The school had been founded as an alternative to the more conservative Ontario College of Art—it required no prerequisites and operated through loosely structured workshops. It attracted students and instructors associated with Toronto’s Spadina art scene: Robert Markle (1936–1990) and Gordon Rayner (1935–2010) were teachers, and Alex Cameron (b.1947) and Arthur Shilling (1941–1986) were students. Most likely, Iskowitz’s involvement at the New School consisted of informal class critiques or the occasional guest talk. Daniel Solomon (b.1945), a friend who taught a few classes from 1969 to 1973, wrote: “Iskowitz would not have been a big part of that school. I doubt Gershon would have enjoyed teaching. He would not have had the patience for it.”

Artistic Transformation

A key moment in the Iskowitz story—and mythology—is the breakthrough that occurred in his painting following a conversation with photographer John Reeves (1938–2016), who told Iskowitz he saw an “aerial perspective” in his work and his palette. Iskowitz applied for and received a Canada Council travel grant in 1967, which he used to visit Churchill, Manitoba. The trip probably took place in the summer of that year, summer being when “recreational” flying is easy and the full-colour landscape spectrum is visible below. Once there, Iskowitz chartered an aircraft to fly over the sub-Arctic landscape and the coast of Hudson Bay.

Churchill is situated at the juncture of three ecological regions: a boreal forest of fir and spruce trees to the south, the Arctic tundra to the northwest, and Hudson Bay to the north. The vast spaces and the brilliant crystal-clear colours he saw below through the scattered cloud cover amazed Iskowitz—he felt he had found the terrain that fitted his particular sensibility. In September 1971 he flew north again, this time to James Bay, and in 1973 and 1975 he visited the area around Yellowknife. Iskowitz frequently returned to these northern experiences for the rest of his life with works in oil and watercolour.

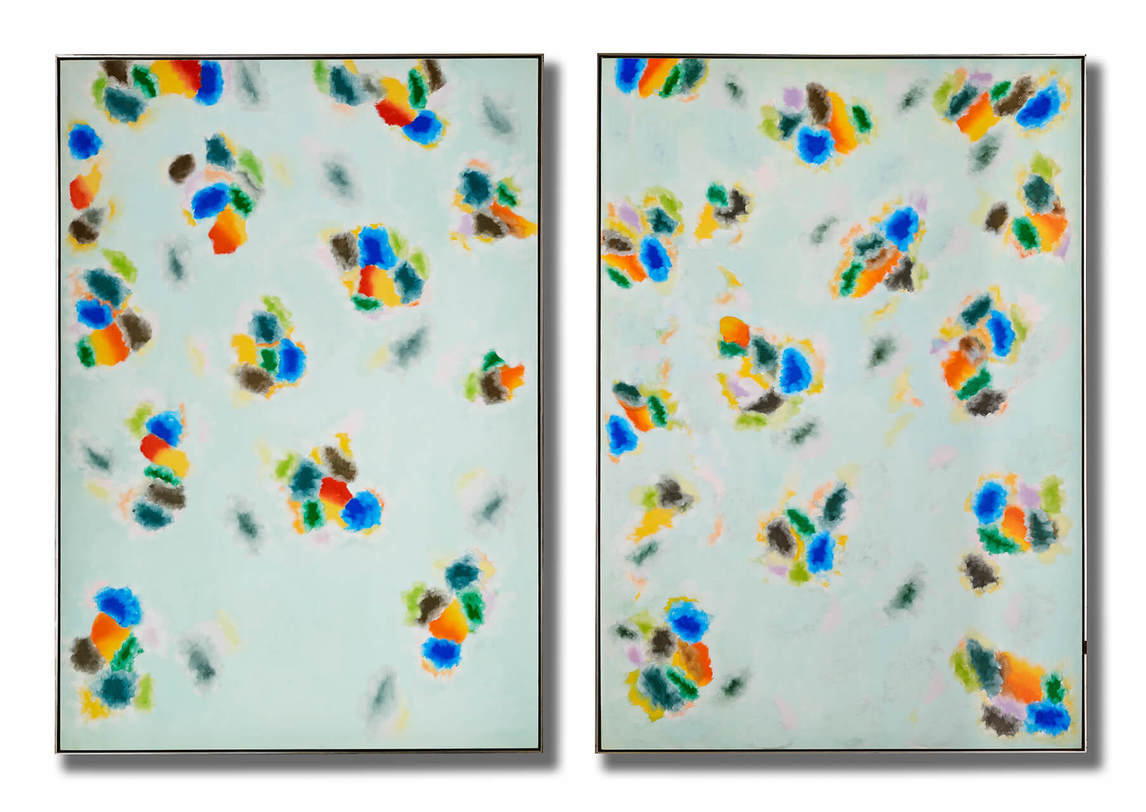

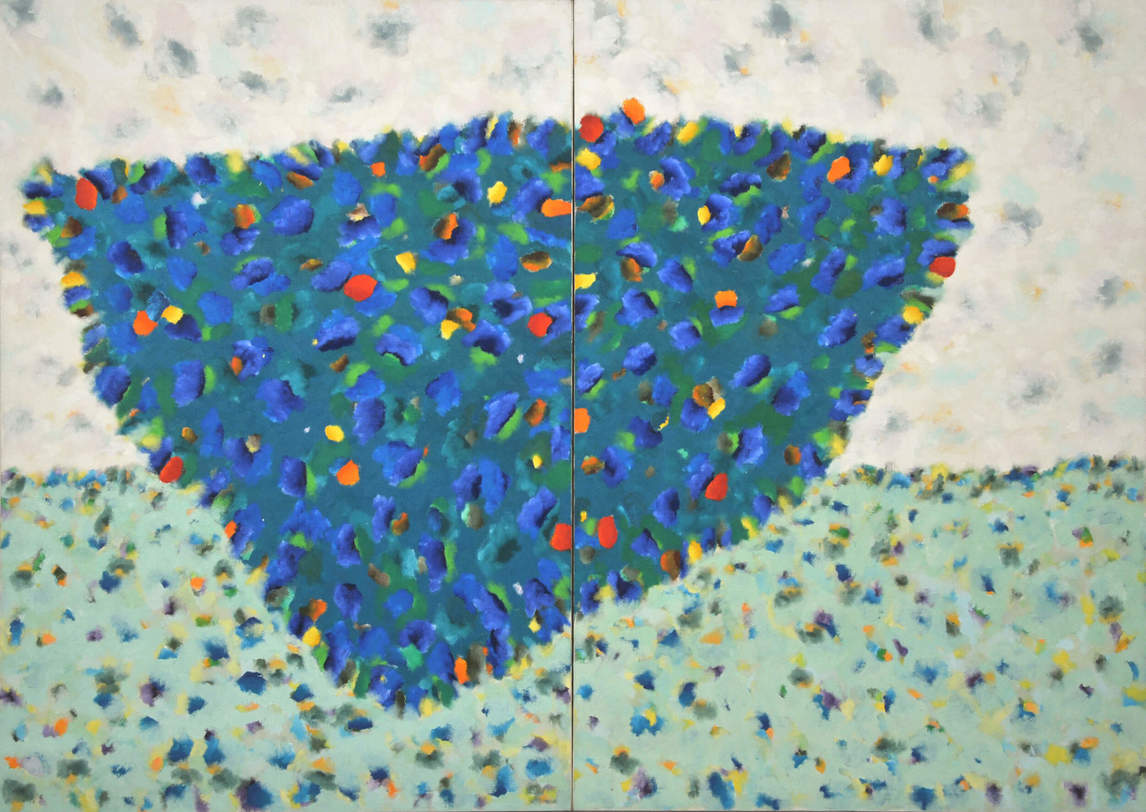

On his return to Toronto, Iskowitz’s art snapped into a more complex abstraction, and he painted much larger works than before. The groundwork for this new creative inspiration had, however, already been laid in his Parry Sound works, with paintings such as Summer Sound, 1965, which had delicate cloud-like trails. In the immediate post-Churchill period, he produced Seasons No. 1—a diptych measuring an epic 254 by 355.4 centimetres—and Seasons No. 2, both 1968–69. The titles were inspired by Baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi’s violin concertos The Four Seasons (1721–25), music Iskowitz loved and often listened to as he painted.

Both Seasons works were included in his solo exhibition at Gallery Moos, February 17 to March 2, 1970; Seasons No. 1 was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada. This show also included thirteen smaller-scale Lowlands paintings, representing Iskowitz’s impressions of the landscape as the aircraft swooped down. They were a “prelude” to his large-scale Uplands series—reflecting his impressions as the aircraft surged upward. The first of the Uplands paintings, three-panelled, is dated 1969–70. It was selected in 1970, along with Seasons No. 2, for the exhibition Eight Artists from Canada organized by the National Gallery for the Tel-Aviv Art Museum in Israel. Iskowitz was the only artist not born in Canada. Painters Charles Gagnon (1934–2003), John Meredith (1933–2000), and Guido Molinari (1933–2004) were among the other artists included.

Over the following years, Iskowitz garnered widespread recognition and many awards. In 1974 he was elected a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Several group and solo exhibitions in New York followed, with the New York Times calling him “extremely gifted in selecting and arranging lyrically beautiful colours that coalesce into a radiant composition.” Iskowitz was also selected for travelling exhibitions across Canada, including to the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and the Glenbow Museum. In 1977 he received the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Medal and was represented in the Seven Canadian Painters show that toured Australia and New Zealand.

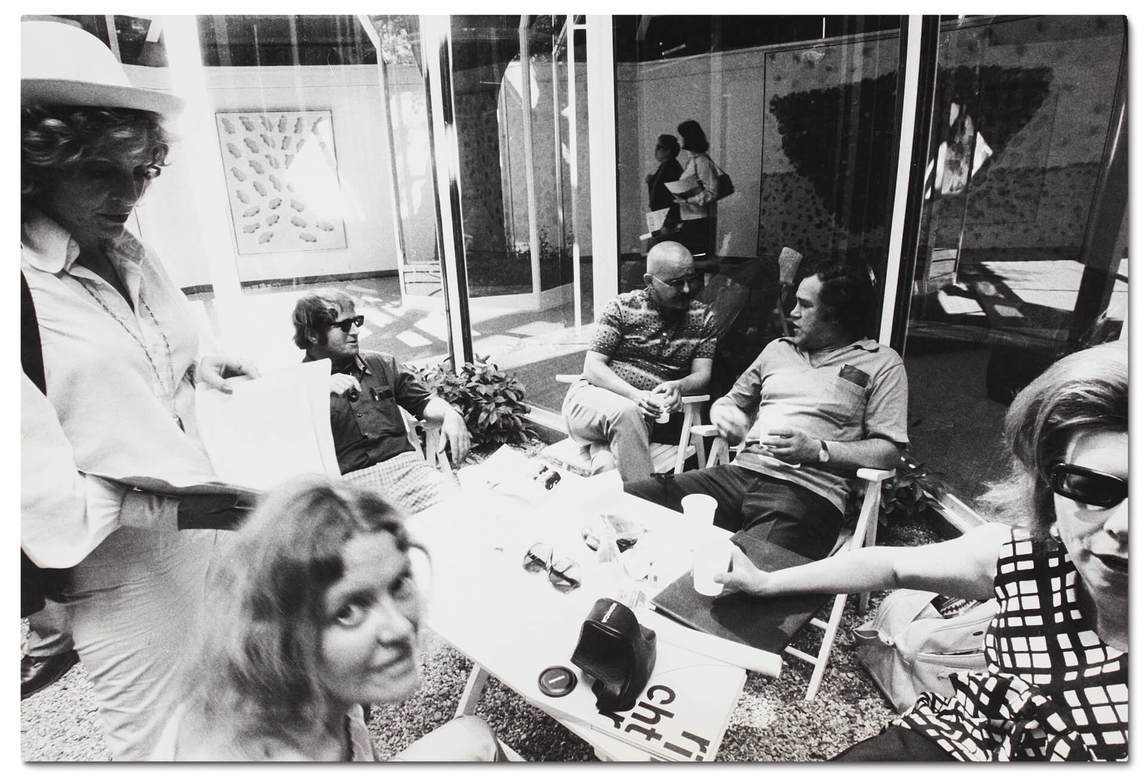

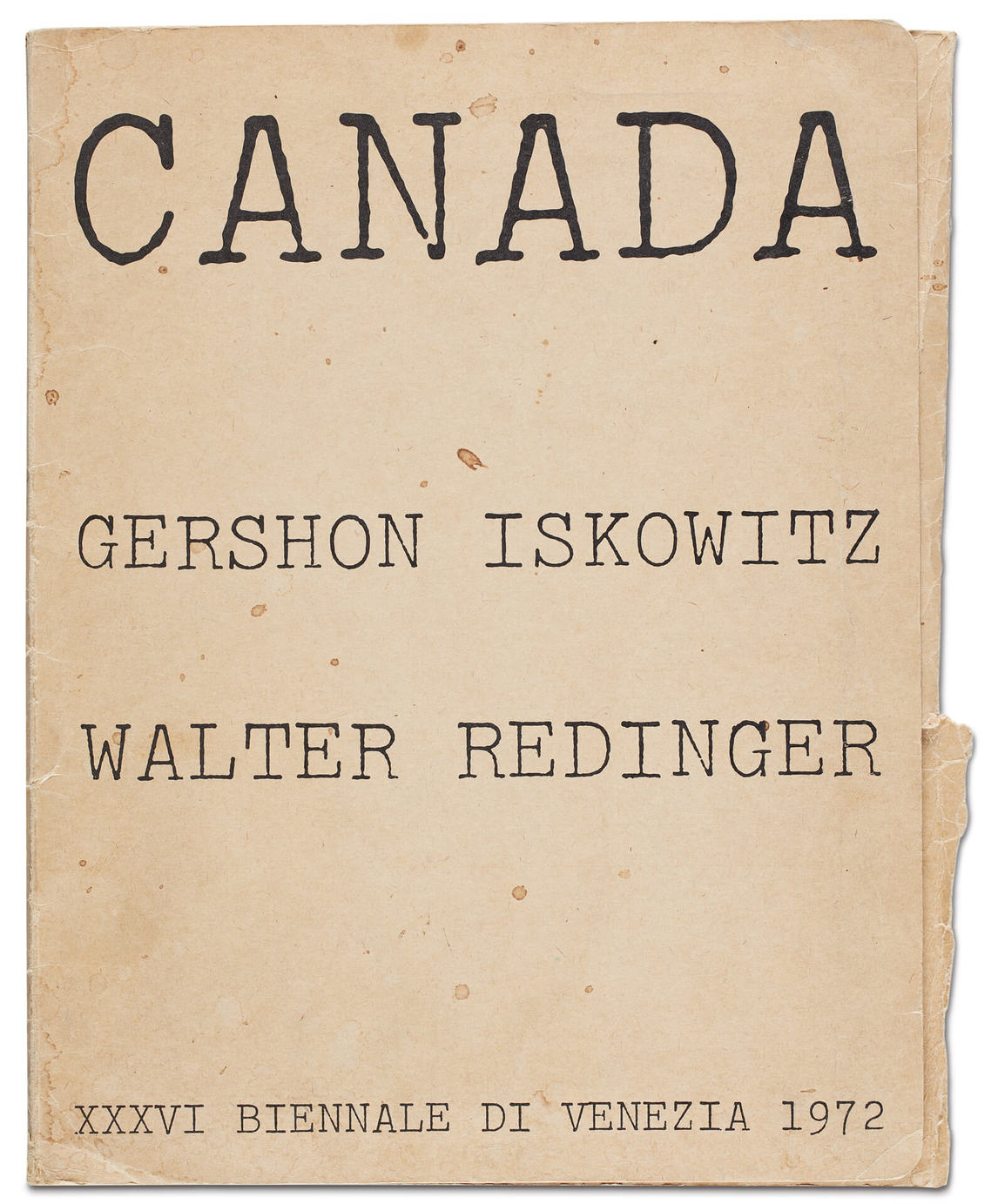

In 1972 Iskowitz was chosen by the National Gallery, along with sculptor Walter Redinger (1940–2014), to represent Canada at the Canadian Pavilion for the Venice Biennale. Four Uplands diptychs were shown in this prestigious exhibition, and Iskowitz’s selection affirmed that he was considered an artist of merit in Canada. Iskowitz protested that “the biennale didn’t help my art—but it makes me feel good.” Walter Moos agreed: “For Gershon the biennale was a high point. It gave him that added assurance he could do even better art.”

An Artist of Routine

Iskowitz’s personal life was simple: once he settled into his own space on Spadina Avenue, he followed the same routine for the rest of his life. He painted at night, under artificial light, and never worked on more than two paintings at once. He had few possessions, and he kept the studio very neat. As described by filmmaker and art historian Peter Mellen: “Canvases carefully stacked against the wall. Paint tubes neatly laid out in long rows. Everything in its place.” Daniel Solomon (b. 1945) noted:

He seemed to paint every day but there was never much smell of oil paint in his studio. He was a very tidy and organized painter. I never saw him in the act of painting. He kept that private [and] would never show me a work in progress, just finished paintings. On Tecumseth [after 1982] he had large white curtains installed on the walls to cover works in progress.

Iskowitz’s routine ensured he was part of an artist’s village where he felt comfortable. It was roughly bordered by Tecumseth Street to the west, Yonge Street to the east, King Street to the south, and Scollard Street to the north. He could walk to Gwartzman’s Art Supplies, at 448 Spadina, where he purchased the painting materials he needed. He frequented artists’ hangouts: Grossman’s Tavern, south of his Spadina studio; the Pilot Tavern (first on Yonge north of Bloor, then on Cumberland Street); and later the Wheatsheaf Tavern at the intersection of King and Bathurst streets. At the dinner hour he had a regular table at La Cantinetta, and later La Fenice, owned by his friend Luigi Orgera. He always dressed respectably but never for fashion; his signature “fisherman’s cap,” recalling those worn by men in his youth, was British-made by Kangol.

Iskowitz’s Canadian experience could be described as a simple life driven by one thing alone—painting without encumbrance. If Iskowitz was quiet by nature, by all accounts he was confident. He did not seek approval but graciously accepted it as it came. Daniel Solomon summarized: “[Iskowitz] had a healthy sense of ego and he knew that he was a good painter—and that seemed to be what mattered. He was definitely a loner and very guarded and also very regimented in his routines.”

Iskowitz maintained his privacy, but over the years he became quite social. Among his friends were younger artists who lived nearby: Solomon, David Bolduc (1945–2010), and John MacGregor (b.1944). Gordon Rayner (1935–2010) had a studio in the same Spadina building. Apart from trips within Canada and New York related to exhibitions, the only two documented trips outside of North America were to Venice for the Biennale in 1972, and for the opening of his retrospective at Canada House Gallery in London, England, in 1983. Solomon recalled: “He did wonder why young people wanted to travel to Europe for pleasure; he saw Europe only as a nightmare to escape.” Iskowitz made a new beginning in Toronto, and his life folded into a quintessentially Canadian émigré/diasporic experience: to be self-made without assimilating pressures, to have an individual dream and not conform to a collective one.

A Lasting Legacy

In 1982 the Art Gallery of Ontario held a retrospective of Iskowitz’s work. Such exhibitions were not common for living Canadian artists in major institutions at the time. It confirmed Iskowitz’s stature as an artist in Canada—only sixteen years after his first, modest public gallery exhibition. Iskowitz appreciated the honour—and he decided to give up his rented studio on Spadina and purchase a one-storey building at 58 Tecumseth Street, southwest of downtown.

The retrospective offered the first opportunity to view the whole arc of Iskowitz’s work to that point and to study it in-depth. The show travelled to four other major public galleries across Canada and to Canada House Gallery in London, England. In hindsight art historian Roald Nasgaard writes: “It was impossible to not be moved by these richly luminous, often intensely hued pictures, so exquisitely poised at that moment when landscape references dissolve into the tangibility of colour and paint.”

As the retrospective was concluding, Iskowitz, who had no close family, set up a foundation as his lasting legacy. He wanted his estate (both savings accumulated from the sale of his work, now commanding high prices, and his new property) to provide financial support to artists through an annual prize. He stated:

It’s very important to give something so the next generation can really believe in something. I think the artist works for himself for the most part. Every artist goes through stages of fear and love or whatever it is and has to fight day after day to survive like everyone else. Art is a form of satisfying yourself and satisfying others. We want to be good and belong. That goes through history; we’re striving for it.

The Gershon Iskowitz Foundation was granted charitable status in 1985. Its charter was forged by Walter Moos and lawyer Jeanette Hlinka, who became the first trustees together with Iskowitz himself. Independent museum consultant Nancy Hushion was appointed executive director in 1989. The prize was initially administered through the Canada Council and awarded by an independent jury—Iskowitz maintained a hands-off approach to the award. The first two prizes, the only ones to be granted while Iskowitz was alive, were given to Louis Comtois (1945–1990) in 1986 and to Denis Juneau (1925–2014) in 1987. As recorded on the foundation’s website:

The impetus for the Prize was Gershon’s grateful disbelief when he was awarded his 1967 Canada Council travel grant and the boost it gave to his painting at a time when he felt his career was in a lull. With no surviving family, a practical question he faced was the future of his estate. His solution was simple enough. Just as he had received support from the Canada Council, he wanted to give his money to artists to help them along.

Gershon Iskowitz died in Mount Sinai Hospital on January 26, 1988, after having been hospitalized there in October 1987. His simple life in Toronto had been ordinary in all respects but one—his work. By 1960 Iskowitz’s studio was a refuge where, painting alone at night, he could imagine and create a world of positive experience through colour and form. This daily routine affirmed a new life and freedom, one Iskowitz shared with fellow artists and friends through his work, and in the public realm through exhibitions. The message was simple and direct: this is who I am, this is life.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements