General Idea produced works in photography, sculpture, and painting, and was especially active in less conventional media such as mail art, video, performance, installation, and artist multiples. Over the course of their twenty-five-year career, they maintained a consistent conceptual approach.

Appropriation

Appropriation is central to many of General Idea’s artworks. The group drew on formats and aesthetics from sources in popular culture and fine art. Through mimicry, General Idea played with viewer’s expectations, reworking familiar forms—from beauty pageants to works of Pop art—in order to prompt critical reflection.

FILE Megazine is a prominent example of General Idea’s appropriation of popular culture formats. FILE mimicked the name and visual culture of the widely distributed American photo magazine LIFE. This parody, including the group’s use of a similar logo, did not go unnoticed by LIFE, which pursued a legal claim against FILE. General Idea also took on media and television, for instance, by enacting a newscast and press conference in Pilot, 1977, and mimicking a news magazine, talk show, and infomercial in Test Tube, 1979. The group also engaged the store format. This can be seen in their earliest shop fronts created at 78 Gerrard Street West in Toronto and in their boutique projects, which included The Boutique from the Miss 1984 General Idea Pavillion, 1980, ¥en Boutique, 1989, and Boutique Coeurs volants, 1994/2001.

The art world itself was also a source of inspiration for the group’s appropriation. For example, General Idea’s performance XXX (bleu), 1984, mimicked the actions of a performance by French artist Yves Klein (1928–1962), while also employing his signature colour International Klein Blue. With their work Magi© Bullet, 1992, General Idea appropriated Andy Warhol’s Silver Clouds, 1966, an installation of silver balloons filled with helium. Magi© Bullet is an installation comprised of General Idea multiples: silver pill-shaped balloons, likewise inflated with helium.

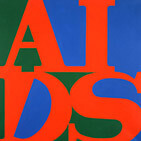

The group’s paintings also drew on key works in the history of twentieth-century art. For instance, the painting series Infe©ted Mondrian, 1994, reworked the signature abstract patterns of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). General Idea’s Mondo Cane Kama Sutra, 1984, is a set of ten paintings that, among other things, echoes the colour and aesthetic of American minimalist painter Frank Stella (b. 1936). One of the group’s most prominent appropriations was their AIDS logo, which reworked American pop artist Robert Indiana’s (b. 1928) painting LOVE, 1966. General Idea first employed their logo in the painting AIDS, 1987, and went on to use it in a range of work that commented on the global AIDS crisis.

Mail Art

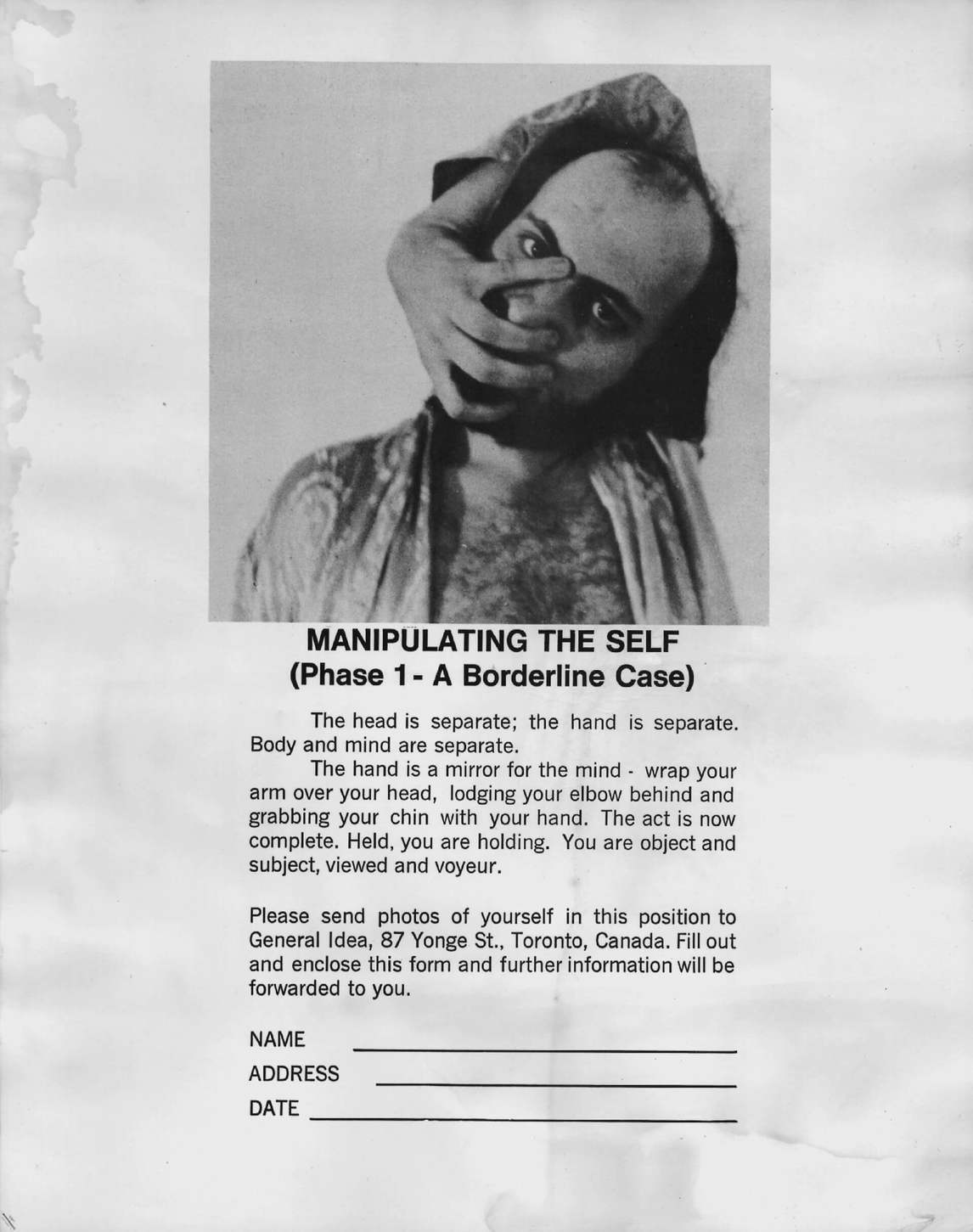

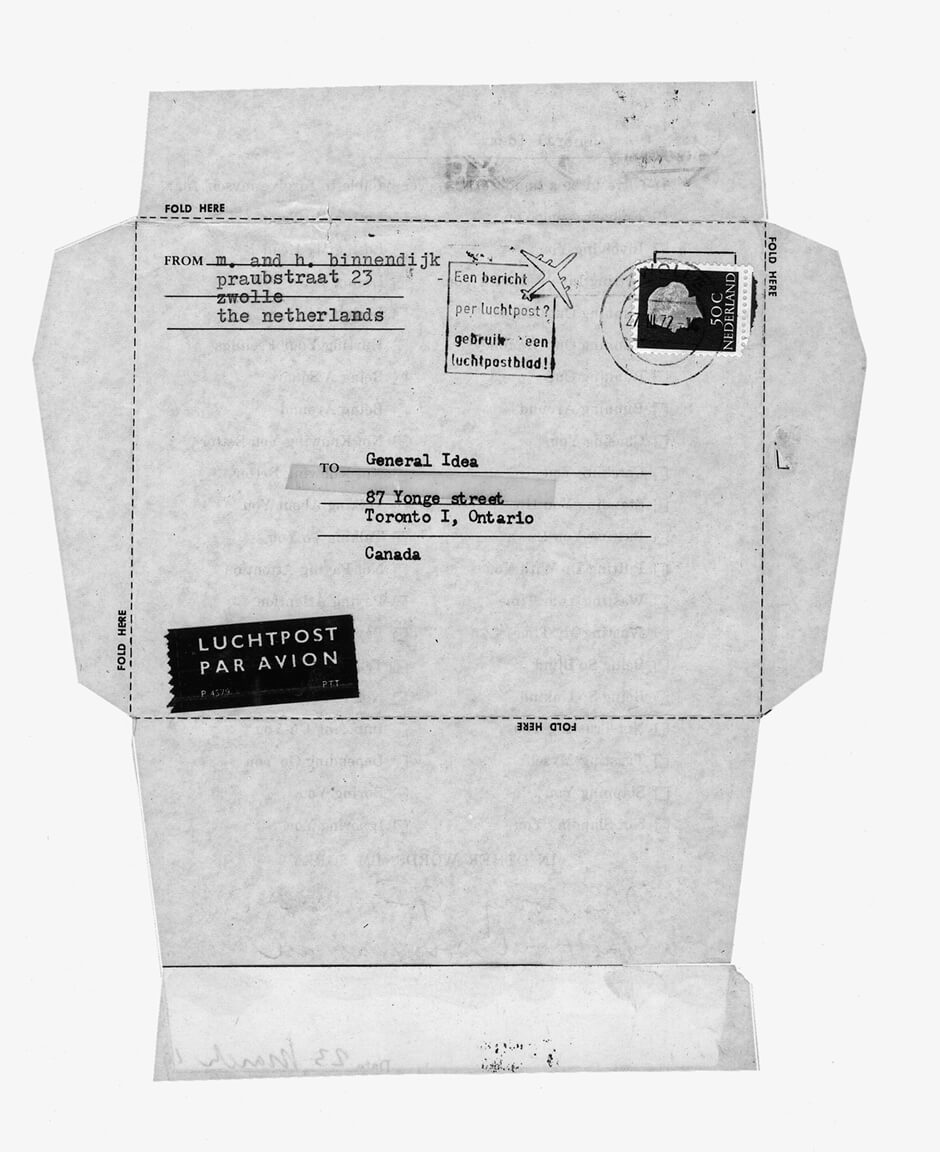

Mail art was a key means of production for General Idea in the group’s early years. A medium that began in the mid-twentieth century, mail art emerged in the 1950s and continues to this day. Mail art is created specifically for the post and is also referred to as correspondence art or postal art. These works are typically produced on a small scale and circulated via a chain-letter-like web of affiliations, often spanning large geographic distances.

General Idea was connected to many mail artists internationally. “We received mail from all over North America … Europe, Eastern Europe, South America, Japan, Australia, and occasionally even India,” explained AA Bronson. “Mail came from Gilbert & George, Joseph Beuys, Warhol’s Factory, Ray Johnson, various Fluxus artists, and so on.” American artist Ray Johnson (1927–1995) was a key figure in the history of mail art: associated with Pop art, Johnson created the first deliberate mail art network, which he dubbed the New York Correspondance School [sic]. General Idea also corresponded with the Vancouver-based collective Image Bank, founded by Michael Morris (b. 1942) and Vincent Trasov (b. 1947).

Mail art incorporates all manner of images and text, especially mass-produced imagery, which is often manipulated through collage, rubber stamping, and photocopying. The medium functions outside of traditional skilled art production, bypassing the commercial gallery system through postal exchange and thereby creating its own audiences. Mail art promoted alternative formats, the democratization of art forms, and a rejection of the commercial gallery system. Two popular slogans were: “Collage or perish” and “Cut up or shut up,” both of which reference artists’ interest in reworking found materials.

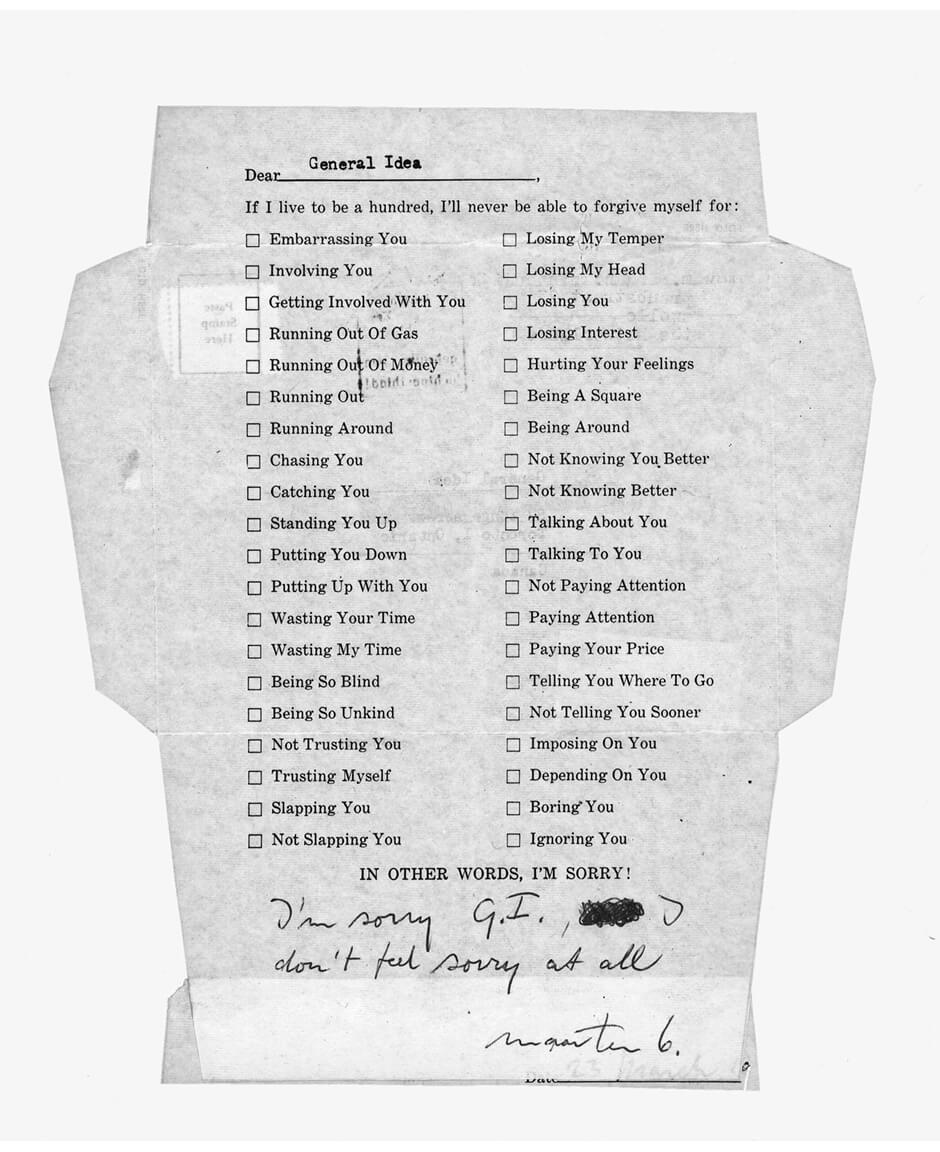

Early mail art by General Idea includes Dear General Idea, if I live to be a hundred I’ll never forgive myself for…, 1972. This work—to which General Idea received forty-three responses—was structured as a one-page questionnaire/apology. Participants were prompted to respond to the eponymous question, checking one or more boxes that corresponded to a list of forty responses. Potential things respondents might never forgive themselves for ranged from “Wasting My Time” to “Not Knowing You Better.”

A key aspect of mail art networks was the assumption of personas, which allowed artists to play with their identities. Often, personas made use of humorous puns or nonsensical and whimsical names. The members of General Idea gradually assumed the personas AA Bronson, Jorge Zontal, and Felix Partz, in the early 1970s.

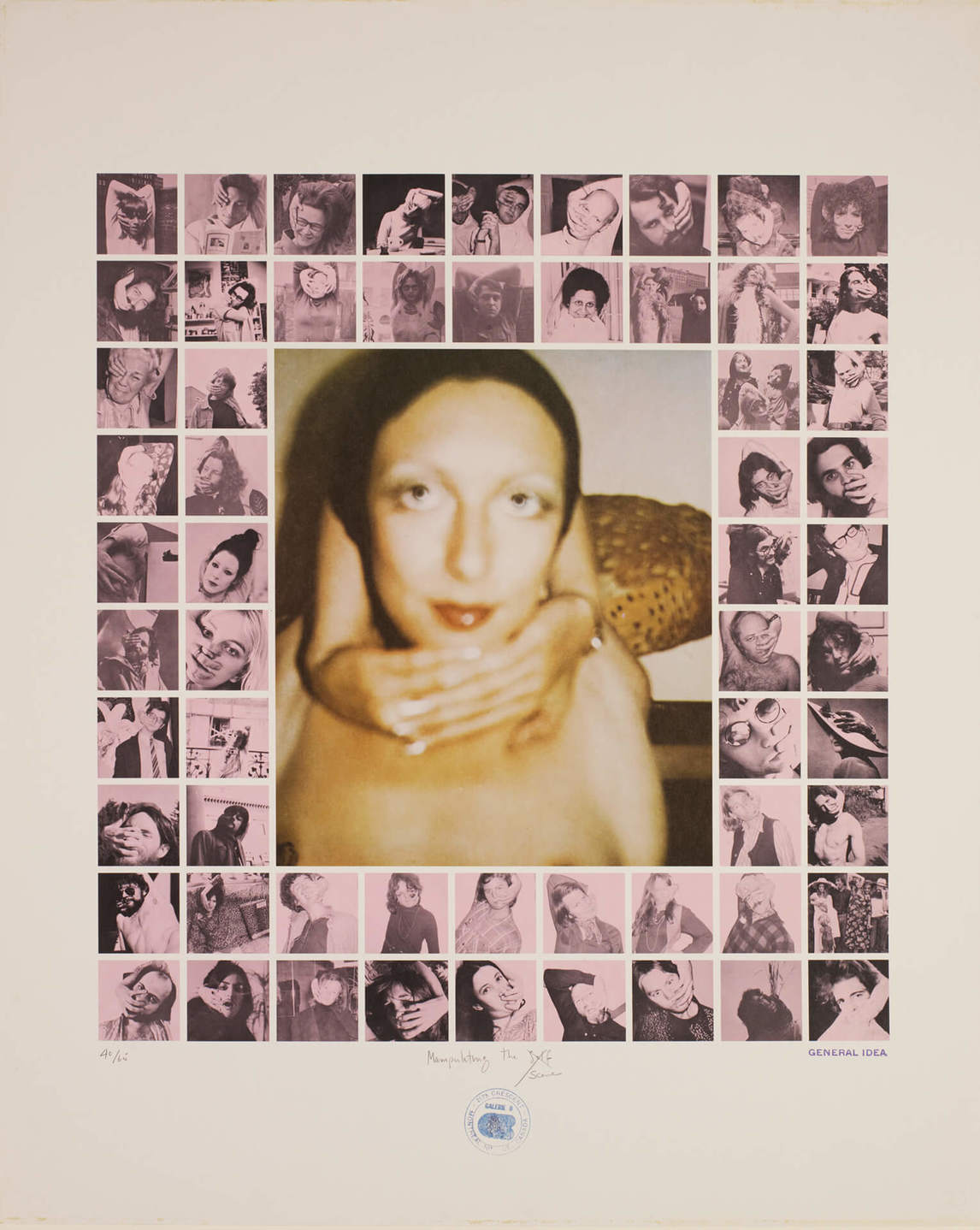

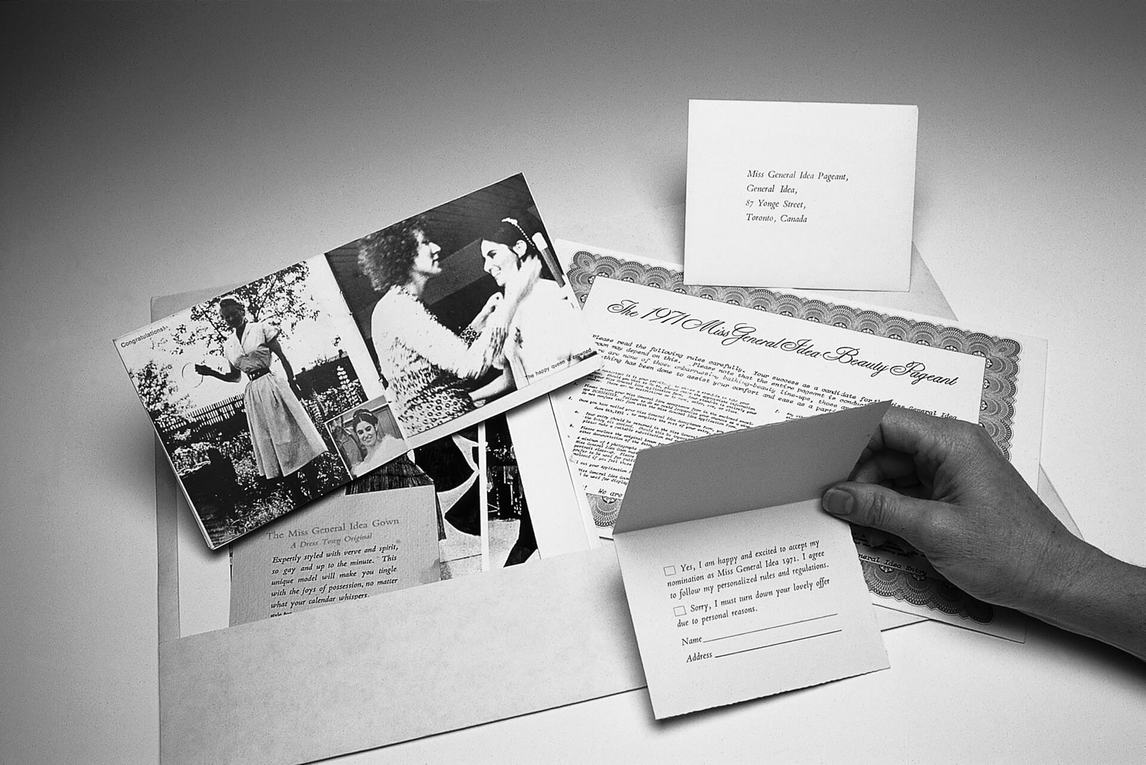

General Idea’s most elaborate and well-known mail art project was The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1971. Sixteen artist-contestants were solicited to participate in this satirical beauty pageant through The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant Entry Kit, 1971. The kit—enclosed in a box marked with a silkscreened logo—contained The Miss General Idea Gown, 1971, a brown taffeta dress to be modelled by all contestants. The box also contained documents explaining the rules and regulations of the pageant, and assorted ephemera conveying the history (real and invented) of the event. Thirteen artists replied to the invitation, submitting photographs of themselves (or models) in the gown, to be evaluated by the pageant judges.

In the 1960s and 1970s, newsletters and publications allowed artists creating mail art to find each other. These formats also documented projects and allowed works to be seen by new audiences. Early issues of FILE Megazine, a publication founded by General Idea in 1972, featured mail art by prominent figures such as Ray Johnson and Robert Cumming (b. 1943). FILE was a key resource as it offered an artist directory of mailing addresses of those interested in correspondence networks and published image-request lists from Image Bank until 1975, allowing artists to submit and draw on specific images for circulation. In the mid-1970s, FILE began to orient itself as a self-contained artist project magazine and moved away from being a mail art resource. This shift mirrored larger developments within the mail art medium.

As FILE evolved, General Idea continued to collect mail art through Art Metropole. Founded by the artists in 1974, Art Metropole is an artist-run centre that exists to this day in Toronto. One of the reasons for its founding was the volume of mail art and ephemera General Idea collected through FILE. Like FILE, Art Metropole promoted the work of other artists, within Canada and abroad, creating new networks and partnerships.

Video Art

Video was central to the work of General Idea throughout the twenty-five years they worked together. The format connected to their interest in performance art and some of their videos from the 1970s document performances staged by the artists.

The advent of the Sony Portapak allowed a single individual to carry and use video recording equipment, portability that helped to spur artists’ use of video. General Idea was captivated by this new technology and used the Portapak in What Happened, 1970. The group specifically employed video to document the What Happened performance and The 1970 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1970, which were both staged at the Festival of Underground Theatre. In turn, the What Happenedinstallation periodically featured video footage of the performance and also included a closed-circuit video set-up. General Idea continued to work with the Portapak for other projects in the period, including Light On Documentation, 1971–74, a black and white exploration of space through mirrors and light. From footage shot while making Light On Documentation, General Idea created Double Mirror Video (A Borderline Case), 1971, which was just over five minutes long. General Idea also used the Portapak to document The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1971.

Among the works that influenced General Idea were Kenneth Anger’s (b. 1927) short experimental film Eaux d’artifice, 1953, and Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, 1954. The works of Canadian artist Michael Snow (b. 1928) were another influence on General Idea, particularly his renowned experimental film Wavelength, 1967. Other influences included Jack Smith’s (1932–1989) Flaming Creatures, 1963, and Susan Sontag’s (1933–2004) 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’” both of which helped to shape General Idea’s approach to camp—a sensibility of “artifice and exaggeration.” Bronson explained, “Basically these films taught us that we should not be ashamed of or avoid camp but rather embrace it.”

As the group began to focus on the narrative of The 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant and its associated Pavillion, they used video to advance the fiction of Miss General Idea. Blocking, 1974, presents footage from a performance at Western Front, an artist-run centre in Vancouver, in which General Idea rehearses audience actions, including reactions and exit, in preparation for the pageant.

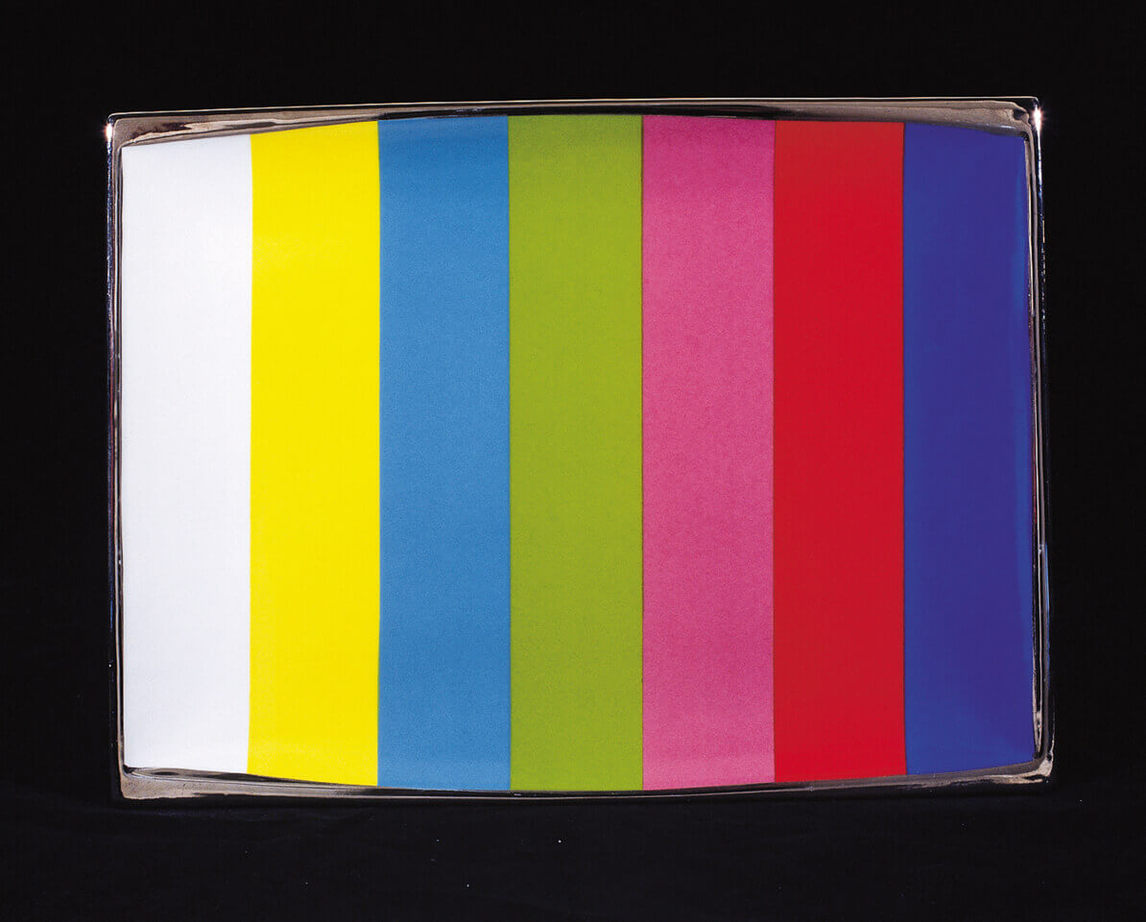

The 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant was also referenced in the video Cornucopia, 1982, which presents the ruins of the Pavillion. In 1977 General Idea asserted that the Pavillion had been destroyed by fire. Cornucopia appropriated the style of a museum documentary to convey the fictional account of the ruins of The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion. Along with an authoritative voiceover that conveyed puns and innuendo, the video features spinning ceramic phalluses and drawings of poodles and ziggurats. Through these fragments and images, the video presents the history of the Pavillion. The video also speaks to General Idea’s larger oeuvre, referencing other projects by the group, including the Colour Bar Lounge.

Many General Idea video projects in the later 1970s and 1980s engaged with television, seeking to subvert some of its most prevalent formats. Pilot, 1977, Test Tube, 1979, Loco, 1982, and Shut the Fuck Up, 1985, were specifically created for public broadcast—fittingly, given the group’s desire to infect the system.” Pilot, for example, uses the structure of a news show to introduce General Idea and their adoption of the pageant scheme, and incorporates some previous audience-rehearsal footage. Test Tube also engages with several popular television formats, including the news magazine, the infomercial, and the talk show.

General Idea helped to facilitate the development and dissemination of video art in Canada, most significantly by founding Art Metropole in 1974. A Toronto-based artist-run centre still in existence, Art Metropole collected and distributed artist videos in a period when few institutions were engaged in these endeavours. The institution also published Video by Artists (1976), a key survey of video art in Canada edited by media-art curator and writer Peggy Gale. Throughout their career, General Idea maintained an interest in video and their works kept pace with advancements in the medium.

Performance Art

Performance art, called body art in the 1960s, used the body in a manner that necessarily highlighted political awareness and was also tied to key developments in alternative theatre.

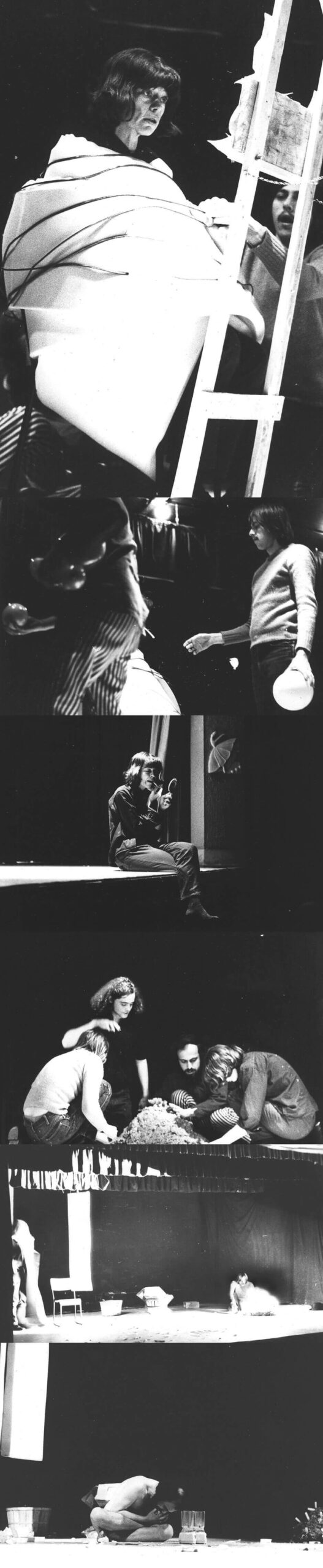

The members of General Idea met in Toronto at Theatre Passe Muraille. Founded in 1968 by Jim Garrard, this progressive company was focused on eliminating the barrier between actors and audience. AA Bronson, Jorge Zontal, and Felix Partz—who were in the process of becoming General Idea—connected through the social scene that surrounded the theatre. Bronson contributed to the company in various ways in the 1960s, including poster and set design. Laundromat Special #1, 1969, a collaborative performance produced as part of Theatre Passe Muraille’s programming, marked the first time the trio performed together. The work comprised a series of actions staged in a room with laundry-soap boxes piled on the floor and an oversized cotton bag labelled “laundry bag” suspended from the ceiling. Match My Strike, performed in 1969 at the Poor Alex Theatre, included Partz, Bronson, Zontal, and Mary Gardner, who used various props, including minced meat, bricks, glass, candles, and a slide projector.

The Miss General Idea Pageant, which shaped the artists’ work in the 1970s, originated in the production What Happened, 1970, a multilayered multimedia event performed by General Idea (and friends) as part of the international Festival of Underground Theatre held at the St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts and the Global Village Theatre in Toronto. The performance was based on a 1913 play of the same name by Gertrude Stein (1874–1946). The work played with the traditional roles of the actor and audience, and General Idea’s version in 1970 fragmented the conventional theatre experience by staging the performance over a three-week period and having the performers record the event in multiple media—from sketching to video. During the intermission for another play being performed at the festival, the group staged The 1970 Miss General Idea Pageant.

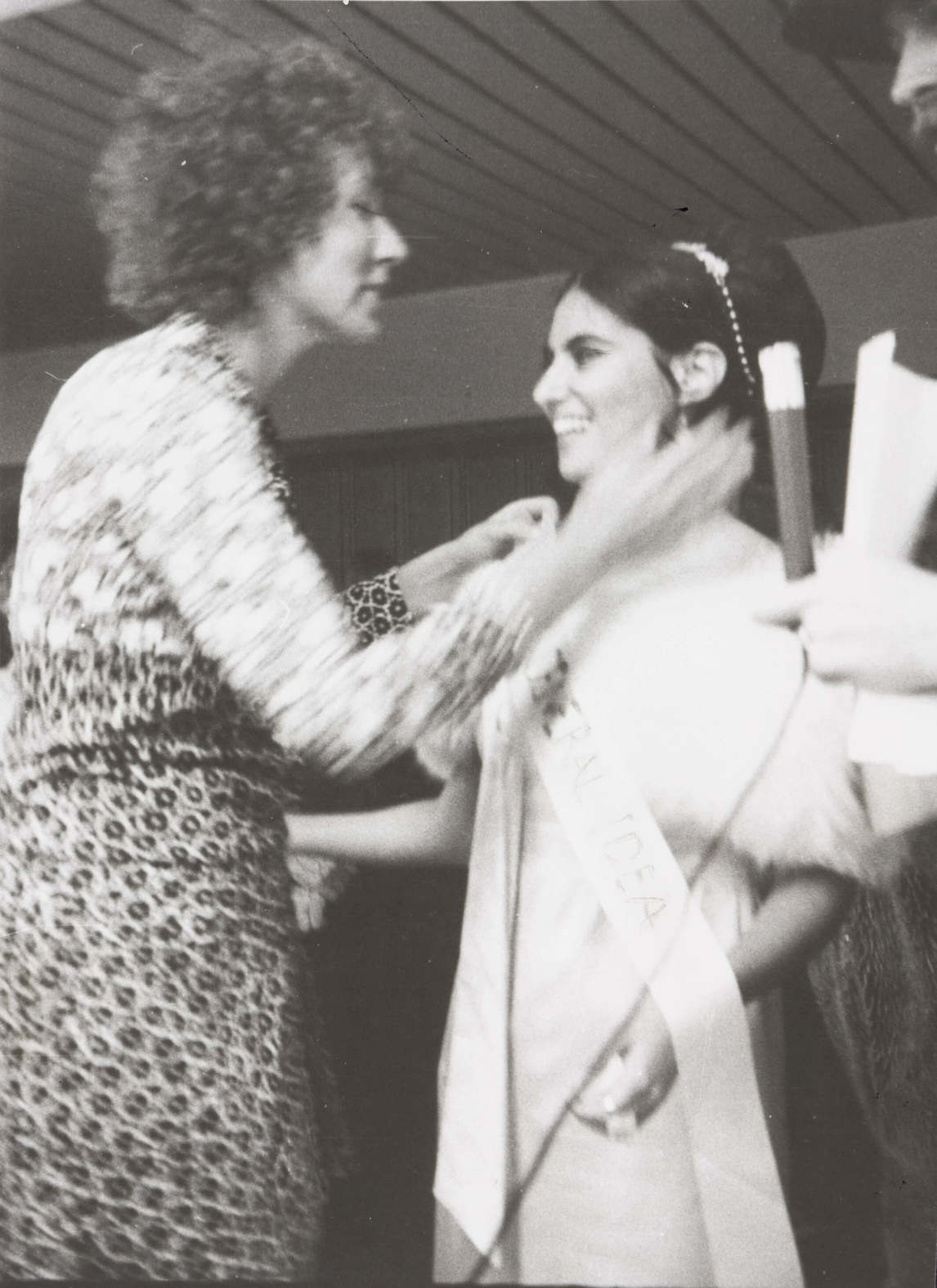

Taking place in the theatre lobby, the pageant was centred on a small platform surrounded by flower arrangements discarded by a funeral parlour. During the talent portion of the pageant, contestant Miss Honey (Honey Novick) showed off her skills on the telex machine. Other contestants were costumed as bears: Belinda Bear, Danny Bear, and Rachel Bear, all of whom sang and danced. The judges declared Miss Honey the winner and crowned her Miss General Idea 1970. The pageant was documented on video. Describing the impact of the event, Partz stated, “Everyone was quite mystified as to what was going on. Because it looked quite real, because Miss Honey was quite a good actress.”

The popularity of the pageant format was of central importance to General Idea and significantly shaped the artists’ work going forward. Pointing to the flexibility and utility of the pageant format, curator and art historian Fern Bayer explains, “The beauty pageant format provided General Idea with a basic vocabulary of contemporary cultural clichés and allowed them to express their ideas about glamour, borderline cases, culture/nature interfaces, the role of the artist as an inspiration cultural device, the body of myths surrounding the art world, and the relationship of the artist to the media and the public.”

The group’s performance XXX (bleu), 1984, spoke to the connections between artists, the art world, and the media, while also referencing art history. It was performed in Geneva, Switzerland, at the Centre d’art contemporain Genève. On a set that played the part of an artist’s studio, the members of General Idea performed an action in which they painted three large canvases with “X” symbols. The colour used was International Klein Blue, created by French artist Yves Klein (1928–1962), renowned for his monochromatic blue paintings. In 1960 Klein famously used nude female models as “brushes” to transfer paint to canvas. His performance was treated with the utmost seriousness—it was a black-tie event, complete with an orchestra that accompanied Klein’s use of the nude women’s bodies to create paintings. General Idea offered a pointed commentary on this by appropriating Klein’s performance but employing three white, faux stuffed poodles, dripping with blue paint, to inscribe an “X” on each canvas.

Installation

Contemporary installations are often described as “site-specific”: they are assemblages of materials intended to reconfigure a particular space and place, often for a limited duration of time. General Idea worked with installations extensively throughout their career. Their interest in the medium intensified via their HIV/AIDS-related work in the 1990s.

General Idea’s initial installations took place within their home at 78 Gerrard Street West in Toronto. The Belly Store, 1969, created with artist John Neon (b. 1944), for instance, made use of the living room of their house. Ambient music played while motorized “bellies” moved in tanks filled with black liquid. In the same room, the group presented George Saia’s Belly Food, 1969. The multiple was made from plastic bottles with custom labels, which were filled with cotton batting. It was sold from a makeshift store counter that featured a cash register. This commercial set up announces the group’s interest in commerce, which was elaborated in installations such as The Boutique from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, 1980, ¥en Boutique, 1989, and Boutique Coeurs volants, 1994/2001.

General Idea also addressed the global AIDS crisis in works such as Fin de siècle, 1990. The group filled a gallery with large Styrofoam sheets, creating a landscape of breaking ice. Within this striking scene, three realistically fabricated harp seal pups sit innocently, serving as a self-portrait of the artists.

In the 1990s the artists made work about the drugs developed to fight AIDS, creating installations including One Day of AZT, 1991, and One Year of AZT, 1991. These two works were often installed in close proximity. One Day of AZT features five Fiberglas pill capsules while One Year of AZT features 1,825 small pills of vacuum-formed styrene. These represented Partz’s respective daily and annual dosages of the antiretroviral drug AZT. Magi© Bullet, 1992, another pill installation, is comprised of custom-produced silver helium balloons. These balloons are shaped like pills and inscribed with General Idea’s name and the title of the work. They fill the ceiling space of the location in which they are presented and, as the balloons deflate, viewers are allowed to bring them home.

Multiples

Multiples were a core aspect of General Idea’s work and thought process. These edition-based works were produced for sharing and circulation. They were low-cost, which meant that they could be distributed in the manner of books, rather than as precious art objects. General Idea’s multiples span a range of materials, from works on paper and posters to chenille crests, rings, scarves, balloons, placemats, and dinner plates. The number of multiples they created varied in each edition according to the artists’ interest and the context of the project—from editions of as few as two to editions of three hundred. In some cases, General Idea produced prototypes that were never realized as editions.

In part, the group’s interest in multiples was tied to their critical interest in consumerism. AA Bronson explained, “General Idea was at once complicit in and critical of the mechanisms and strategies that join art and commerce, a sort of mole in the art world.” The artists promoted General Idea multiples through retail installations such as The Boutique from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, 1980, and ¥en Boutique, 1989. The 1984 Boutique, created in the shape of a dollar sign, made its commercial intentions apparent. Both boutiques were fully functioning kiosks at which General Idea multiples were sold. General Idea’s founding of the artist-run centre Art Metropole is also tied to the group’s interest in multiples: opened in 1974, the Toronto-based institution distributes artist editions to this day.

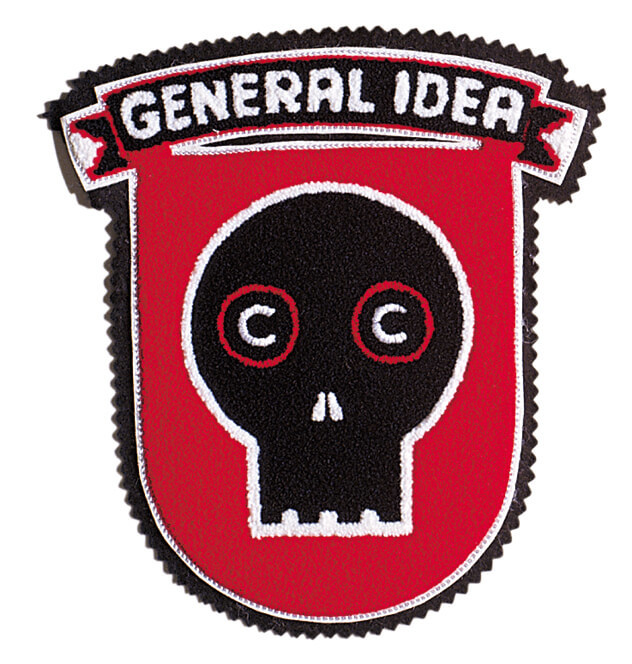

Many General Idea multiples closely referenced their concurrent art projects in other media. For instance, The Getting into the Spirits Cocktail Book from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, 1980, is a bookwork of ersatz cocktail recipes for the drinks the group concocted in the Colour Bar Lounge (which appeared in their video work Test Tube, 1979). Similarly, General Idea translated their ongoing interest in heraldry (evidenced by a series of paintings featuring recurring imagery such as the poodle) into a series of crest multiples. Eye of the Beholder, 1989, for example, is a small chenille crest with a black, white, and red colour palette that shows a stylized skull with two copyright symbols for eyes. Above, the name of the group appears in capital letters.

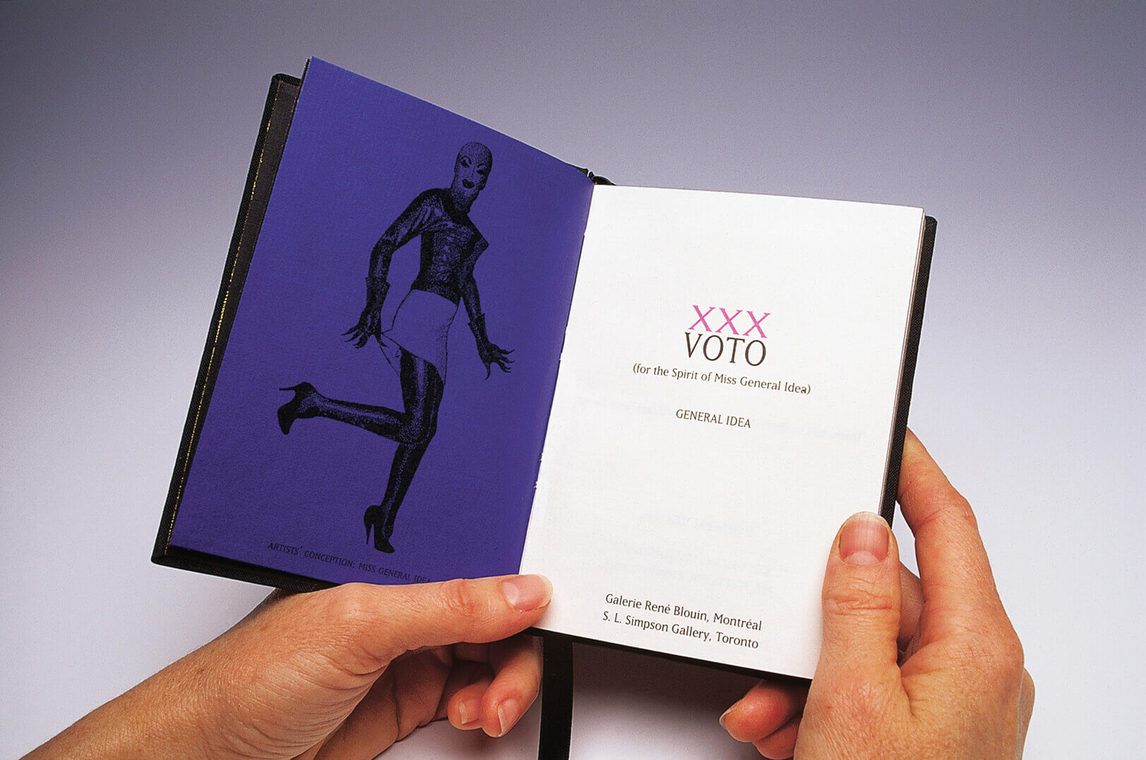

Publications, including FILE Megazine (1972–89), were a key component of General Idea’s multiples. Their final multiple was a book project titled XXX Voto (for the Spirit of Miss General Idea). This poignant reflection on the artists’ long collaboration was published in May 1995, following the deaths of Jorge Zontal and Felix Partz in 1994. XXX Voto is based on a text by Yves Klein (1928–1962), in which he thanks his patron saint for his life. General Idea adopted this concept and dedicated their gratitude to the Spirit of Miss General Idea. The text references the three artists throughout: one line reads, “thank you three times to the third power.” Bronson explained that XXX Voto was a reflection on the life the artists had together.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements