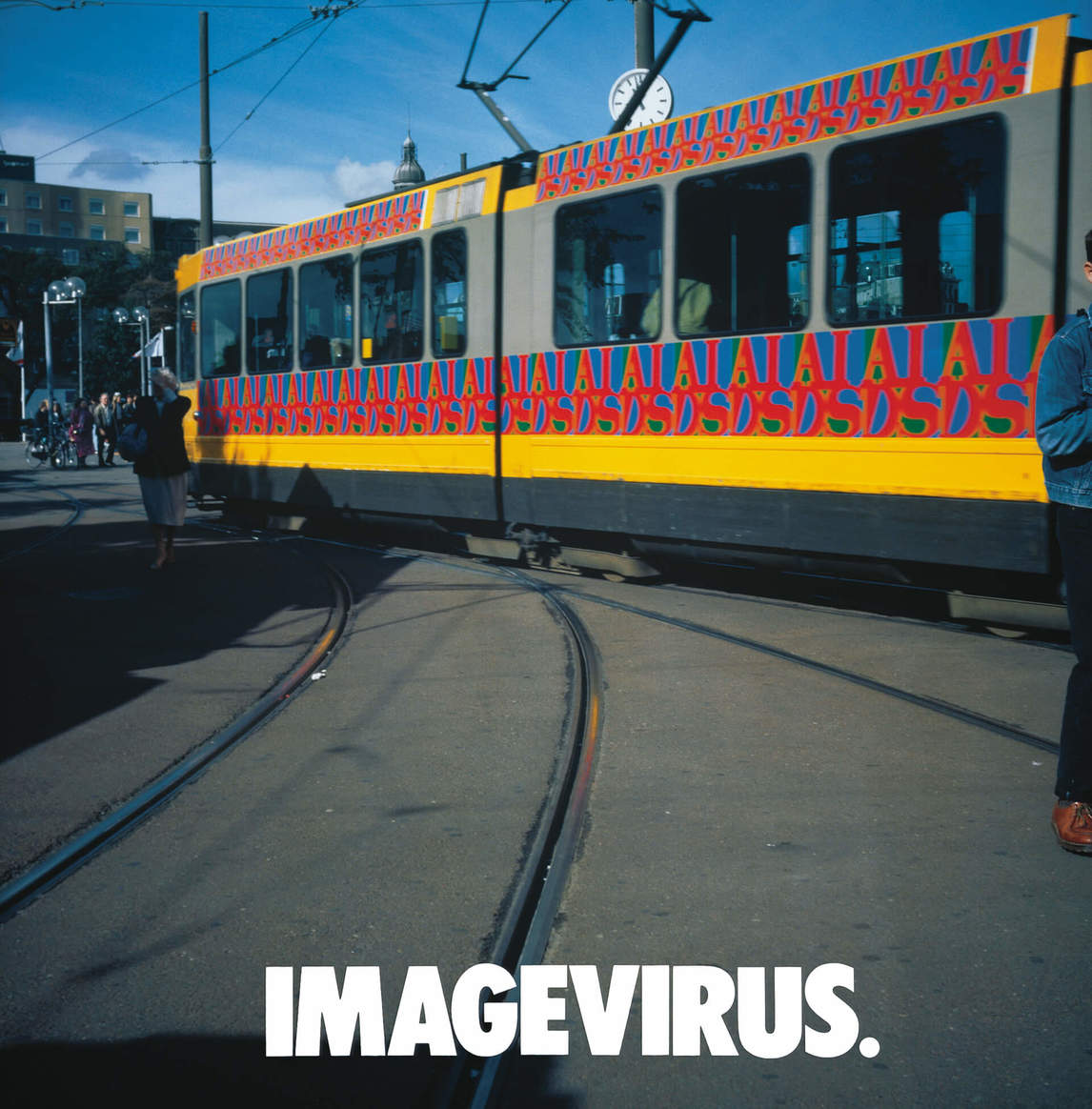

General Idea’s conceptual projects addressed key social issues, including celebrity, media communication and consumption, as well as the AIDS crisis. The group’s artistic statements about queer identity were ahead of their time and pushed boundaries in the art world.

A Conceptual Approach to Collaboration

General Idea embraced a conceptual approach to making art. While they had numerous influences, the collaborative aspect of their work was informed by several factors: the performative work in the 1960s that emerged from Fluxus, Happenings, and Viennese Actionism; their activity within avant-garde theatre, which in the period widely used collective techniques; the filmmaking practices of Mike Kuchar (b. 1942) and George Kuchar (1942–2011) and Jack Smith (1932–1989), who employed their social circle in their films; and Andy Warhol’s (1928–1987) Factory, a site where Warhol and his circle of friends produced art.

“THREE HEADS ARE BETTER” proclaimed a 1978 issue of FILE Megazine, the publication the group founded in 1972. This statement was a cheeky testament to General Idea’s shared vision, and the article explained their consensus-based working model: “Our three sets of eyes perform a single point of view. Other lines of vision are tolerated around the conference table but when out in public solidarity is essential.” In this way, General Idea made clear that the identity of the group superseded the identity of its individual members. The group took on “a single point of view,” and thus considered itself a single entity. Their non-hierarchical, cooperative approach was also tied to the values of community espoused in the 1960s. Additionally, the group composition critiqued the conventional public image of the artist. As General Idea explained, “Being a trio freed us from the tyranny of individual genius.”

General Idea’s partnership was more than a working relationship: it extended to all aspects of the artists’ lives. “[I]t was kind of an odd collaboration,” Bronson explained, “in that we both lived and worked together. So it was a kind of domestic as well as an art relationship.” The group upheld their tripartite structure as a reason for their long-term success and stability between 1969 and 1994. General Idea’s conceptual projects and collaborative working method stand as part of their legacy, especially as collaborative art production has gained ground in the contemporary era.

Queer Identity

As a group of three men who identified as gay, General Idea played with notions of gender and sexuality. Their performances and imagery pushed the boundaries of sexual identity representation. While the group was active, key changes were taking place in North America with regard to LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) rights. In 1968, just before AA Bronson, Felix Partz, and Jorge Zontal met in Toronto, Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau introduced an omnibus bill that reformed Canadian law with regards to homosexuality, as well as abortion and contraception. This law was implemented in 1969, and, amongst other things, it decriminalized homosexuality. That same year, New York City was rocked by the Stonewall riots, a series of violent protests against the police raid of a gay bar in Greenwich Village.

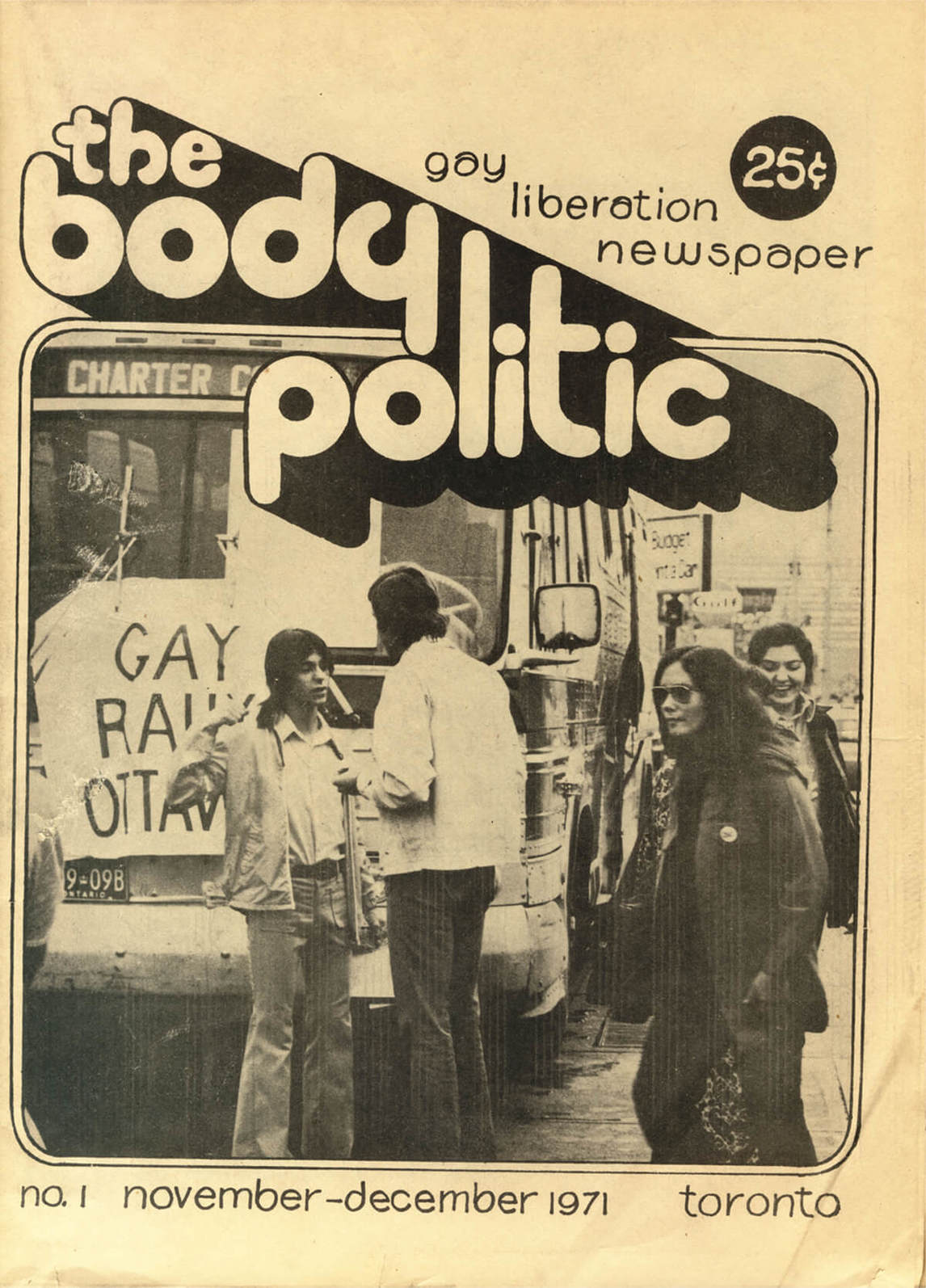

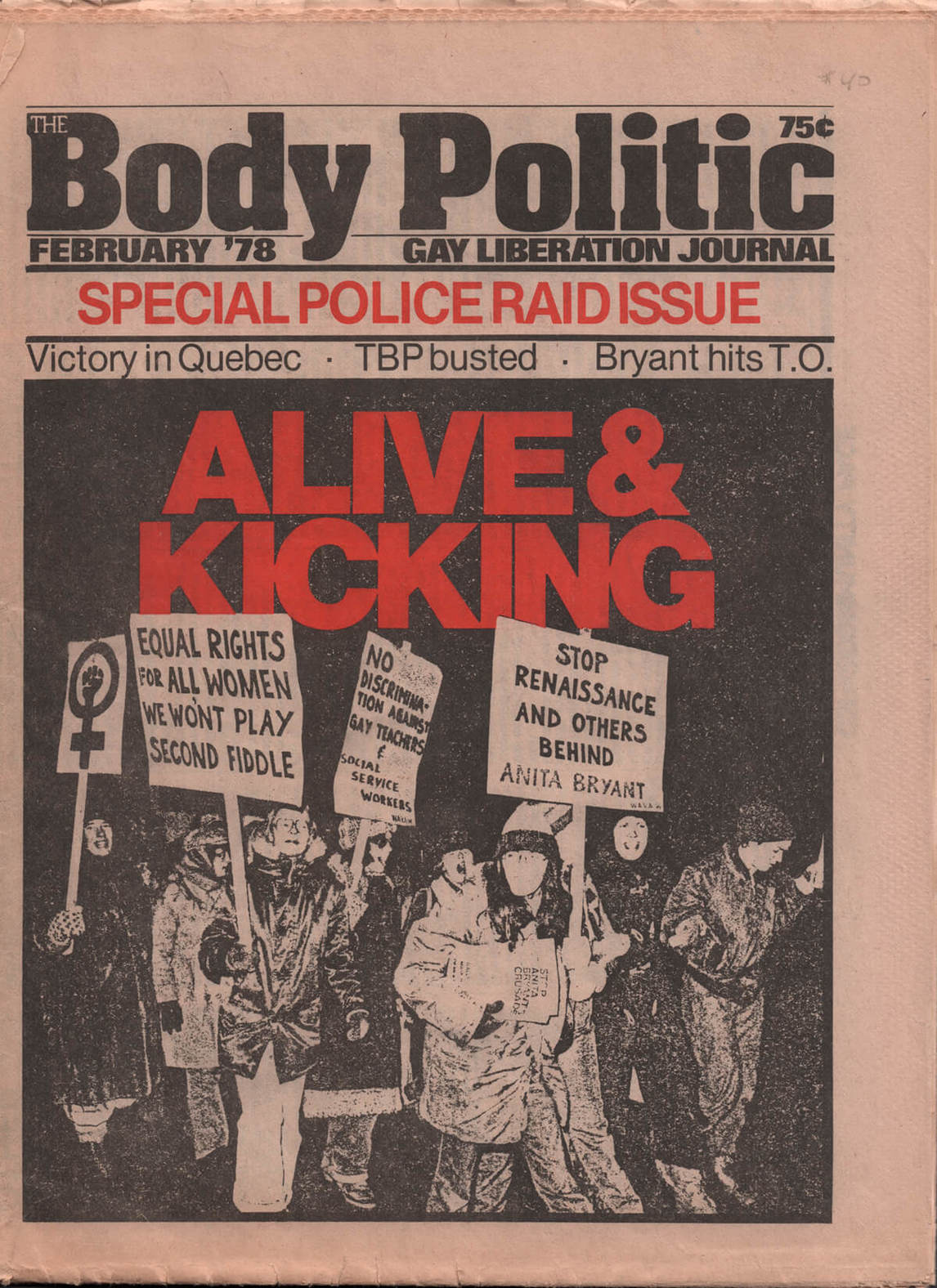

In 1971 in Toronto, shortly after General Idea began producing work, the key publication The Body Politic was founded. Described as “Canada’s gay newspaper of record,” it was a highly controversial and embattled publication. In the same period, other spontaneous actions of civil resistance and community organization occurred. For instance, a series of small-scale picnics on Hanlan’s Point, Toronto Islands, began in concert with civil rights marches. Despite these moments of declaration, equality remained elusive, and there existed widespread violence against and surveillance and repression of LGBT communities. In 1978 The Body Politic was charged with obscenity. General Idea participated in a public demonstration against this censorship in January 1979, contributing a performance titled Anatomy of Censorship, 1979.

The fight for LGBT equality continued in the 1980s. Operation Soap was a pivotal moment in the Canadian fight for LGBT civil rights. On February 5, 1981, the Toronto police coordinated a large-scale raid on four Toronto bathhouses, leading to the arrest of more than three hundred men—including Zontal. This raid led to public outcry and large protests, which galvanized support across the country and reframed the struggle for equality as one of human rights.

General Idea’s work should be understood in the context of this paradigm shift. Though their art is now seen as unabashedly speaking to queer identity, this theme was not addressed by critics until the mid-1980s. In the art world at the time, sexuality was not a topic that could be raised. The artists did not experience censorship; rather, this facet of their projects was simply ignored. Bronson explained, “Sexuality was kind of a dangerous subject in the art world. Sex was never touched upon. And, to call yourself a gay artist would be, of course, the death knell of your career.”

Despite this, General Idea made many brazen and playful references to queer identity in their works, such as Baby Makes 3, 1984/89. In this portrait, Bronson, Zontal, and Partz are depicted in bed together, with the covers pulled up to their chins. Rosy cheeks and softly rounded faces suggest innocence and infantalization. The trio alludes to a traditional nuclear family while also suggesting a queering of this format. This reference to family also reflects the nature of General Idea’s collaboration, as the group’s domestic lives and art production were very much entwined.

Bronson recalls the group’s desire to have critics discuss their work in terms of sexuality and has said the group baited art critics by “being more and more outrageous all of the time.” For instance, Mondo Cane Kama Sutra, 1984, clearly depicts trios of fornicating neon poodles. The poodle was a key symbol in General Idea’s oeuvre, primarily intended as a clichéd image that signifies gayness in mainstream North American culture: Bronson has said, “The poodle stands for the queer artist.” Despite the overt sexual imagery in the paintings, critics discussed these works in relation to the trio’s artistic collaboration. Finally, by 1986, General Idea was written about in terms of queer identity. The shift, Bronson noted, was one of attitude: “Prior to that it was just considered embarrassing or something.”

Following the end of General Idea’s collaboration in 1994, with the deaths of Partz and Zontal, some contemporary scholars—such as Virginia Solomon—have sought to address the queer dimension of the group’s work.

The Medium is the Message

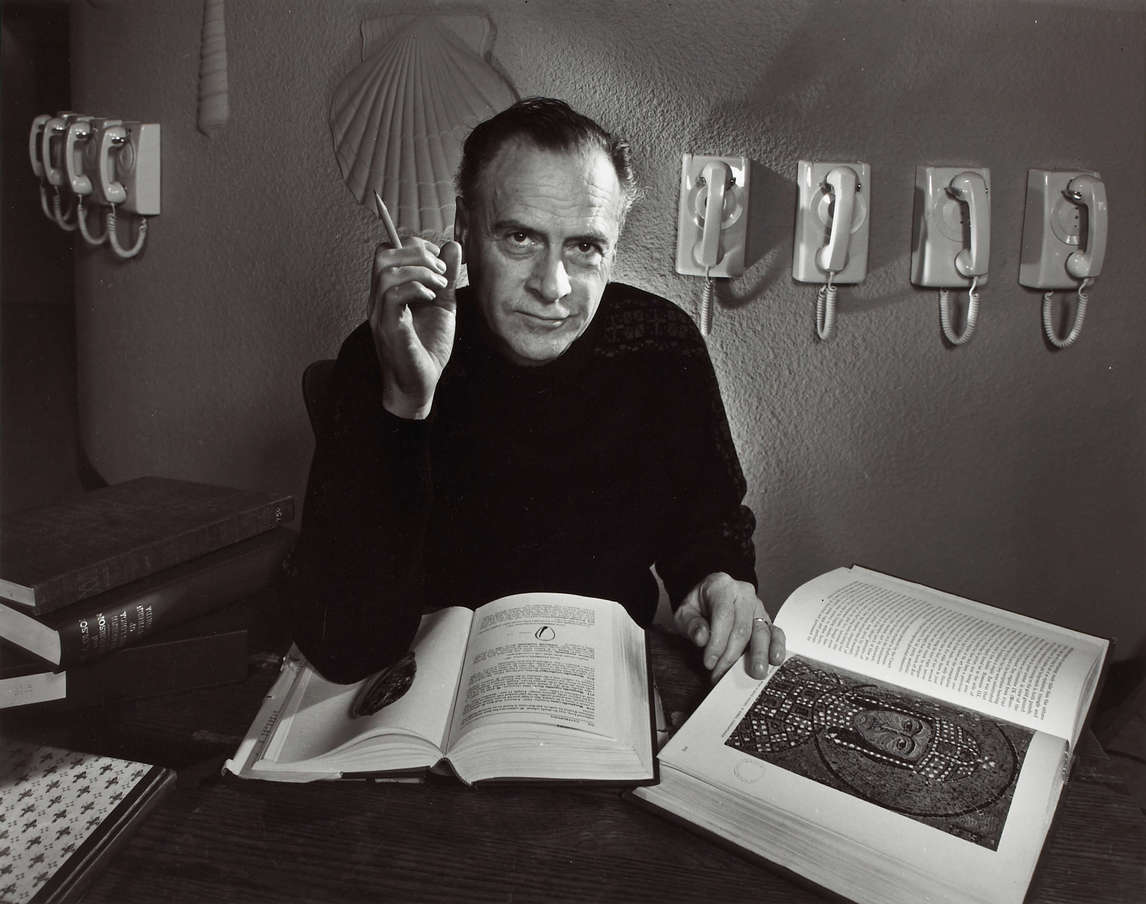

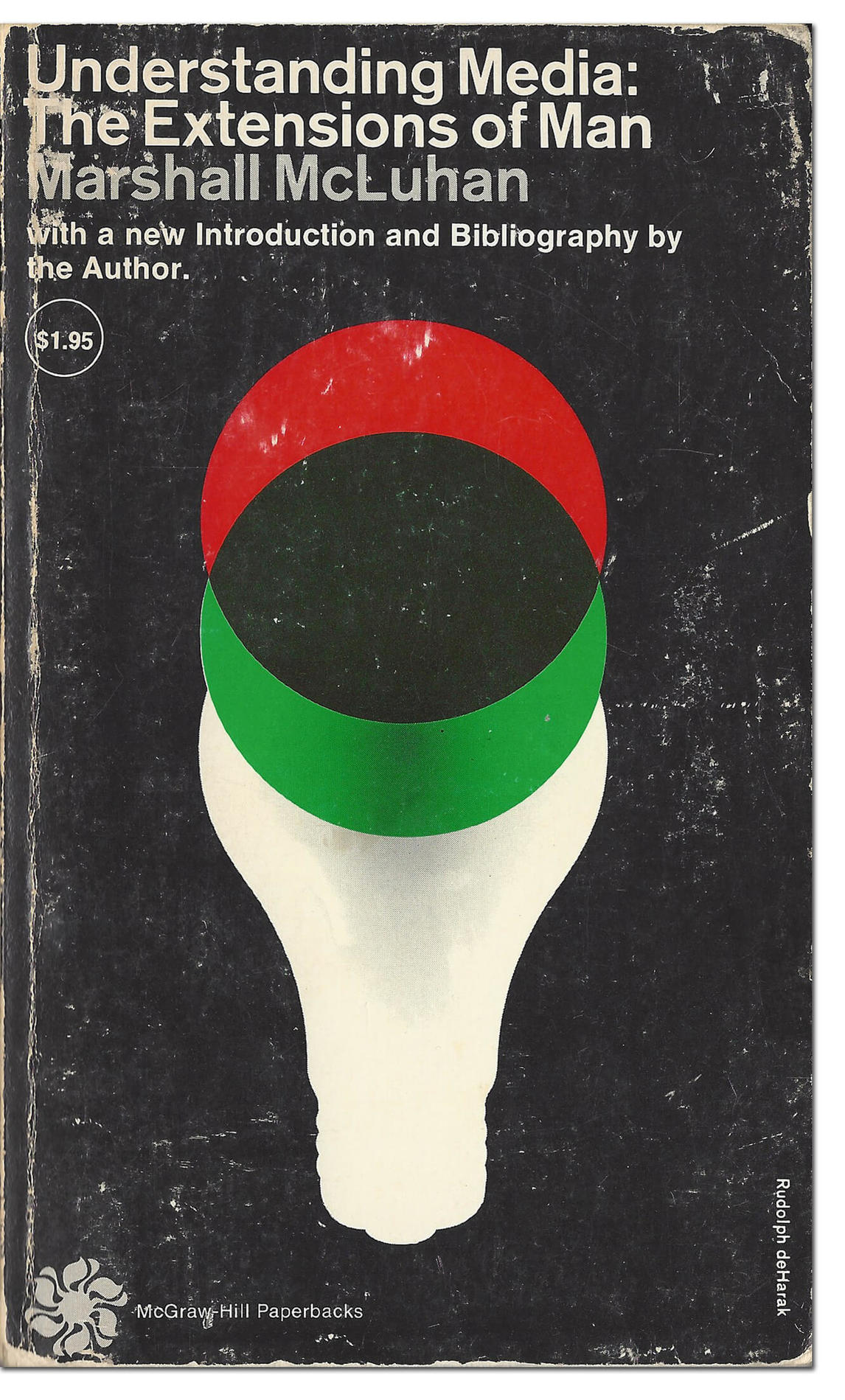

General Idea analyzed and critiqued media and popular culture by appropriating existing cultural structures, such as beauty pageants, magazines, and television formats, and by using mimicry, irony, and humour to subversive ends. A key influence in this regard was Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980), who rose to prominence in the 1960s with his ideas about popular culture, communication technology, and media theory.

In his key writings, McLuhan addresses media and how communications technology shapes the messages it conveys and affects social organization. In Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964, he focuses particularly on television. This text is the source of McLuhan’s pithy phrase “the medium is the message,” which gained widespread popularity.

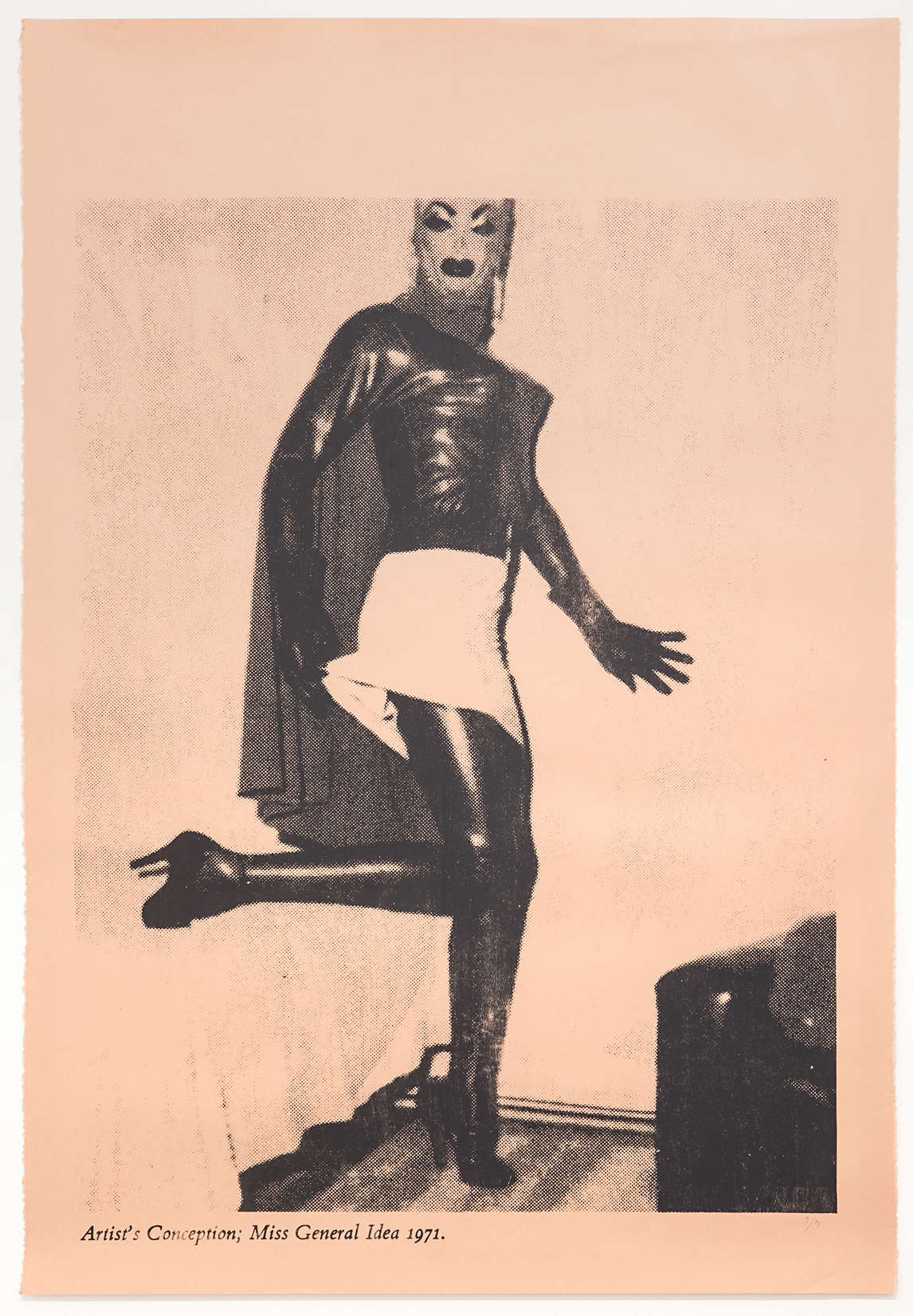

McLuhan had a broad influence on the members of General Idea, who read his books in the 1960s. Though his influence was not limited to their thinking about television formats, McLuhan’s notion that the social effects of media deserve critical analysis informed General Idea’s appropriation of the beauty pageant. This made-for-television structure significantly shaped work the group made in the 1970s, especially the satirical mail art and performance work The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1971. This project allowed General Idea to unpack issues of gender stereotyping and celebrity culture, topics they continued to explore in much of their work.

General Idea’s appropriation of television formats can also be seen in videos, such as Test Tube, 1979, which quotes the structures of a news magazine, infomercial, and talk show. Notably, this work was created for television broadcast—a further infiltration of popular culture.

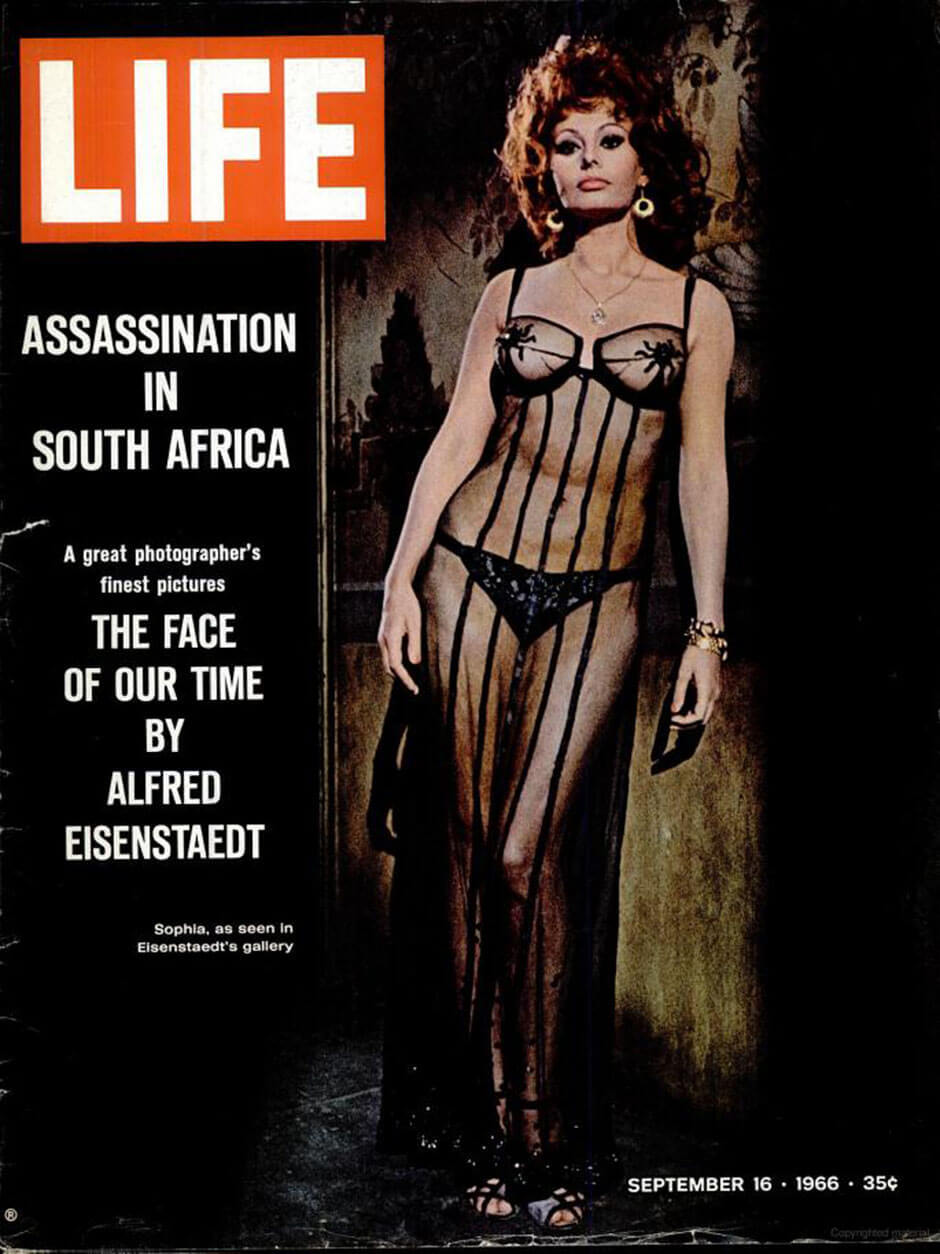

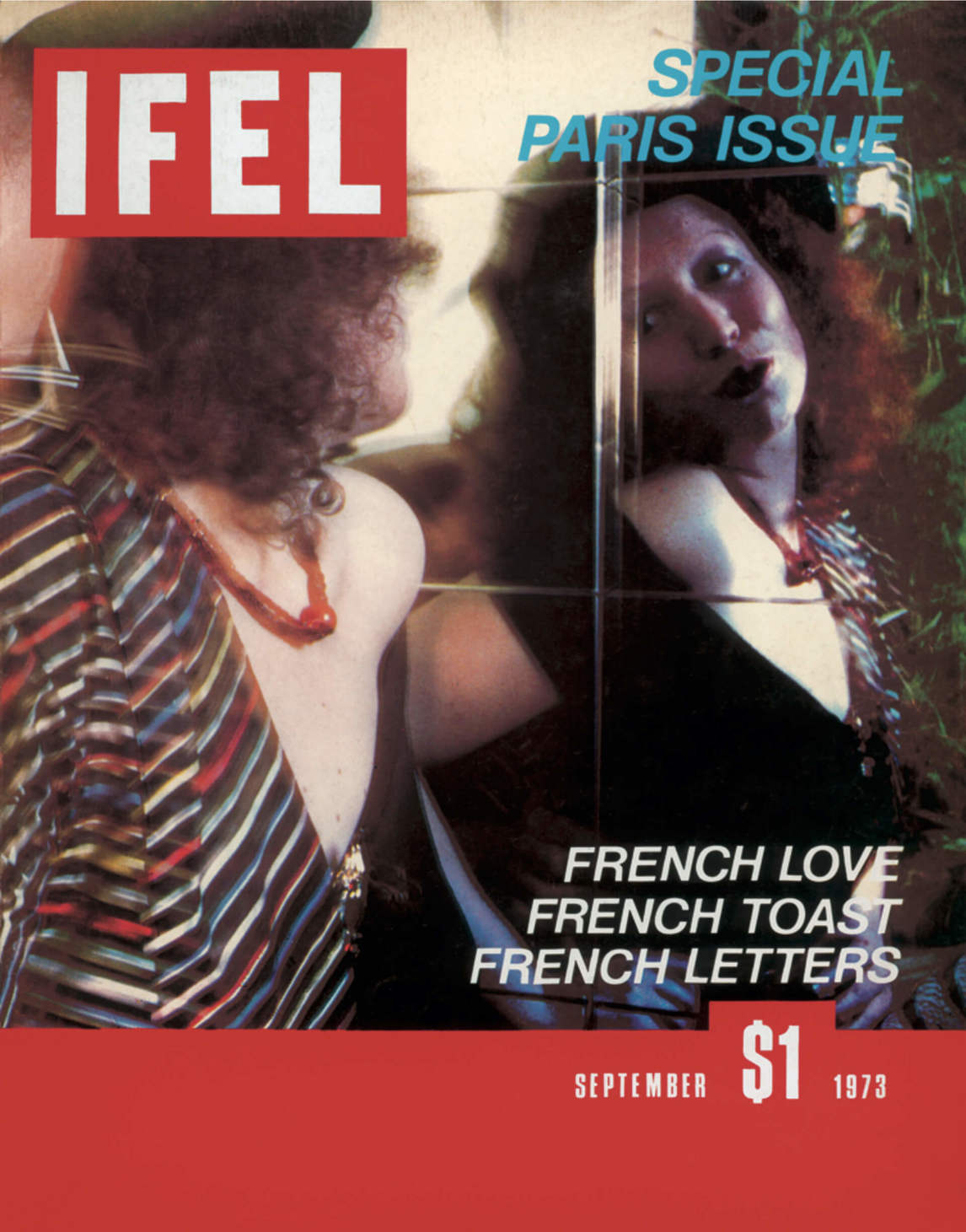

The group’s exploration and appropriation of popular media extended to print culture. In 1972 they created FILE Megazine, modelling the look and logo of the popular American magazine LIFE. As AA Bronson explained, “We wanted something at a normal newsstand that anybody would pick up, just because of familiarity. But then they would find that it was something not at all familiar.”

General Idea’s diverse works, which highlight the artifices of media, reveal the influence of McLuhan’s theories on media and communications. In Bronson’s words, “we were media moguls in a universe of our own making.” Through their appropriation of media and popular culture formats, the trio critiqued and satirized contemporary society and its social structures.

Building a Canadian Art Scene

General Idea was centrally involved in the creation of artist-run culture in Canada in the late twentieth century. They contributed in several different ways and mediums, participating as key artists in the formation of the network of artist-run centres and wielding authority regarding the direction of policy-making. Their efforts were focused through two key platforms: the publication FILE Megazine and the artist-run centre Art Metropole. While part of General Idea’s oeuvre, both initiatives also significantly supported other artists’ projects.

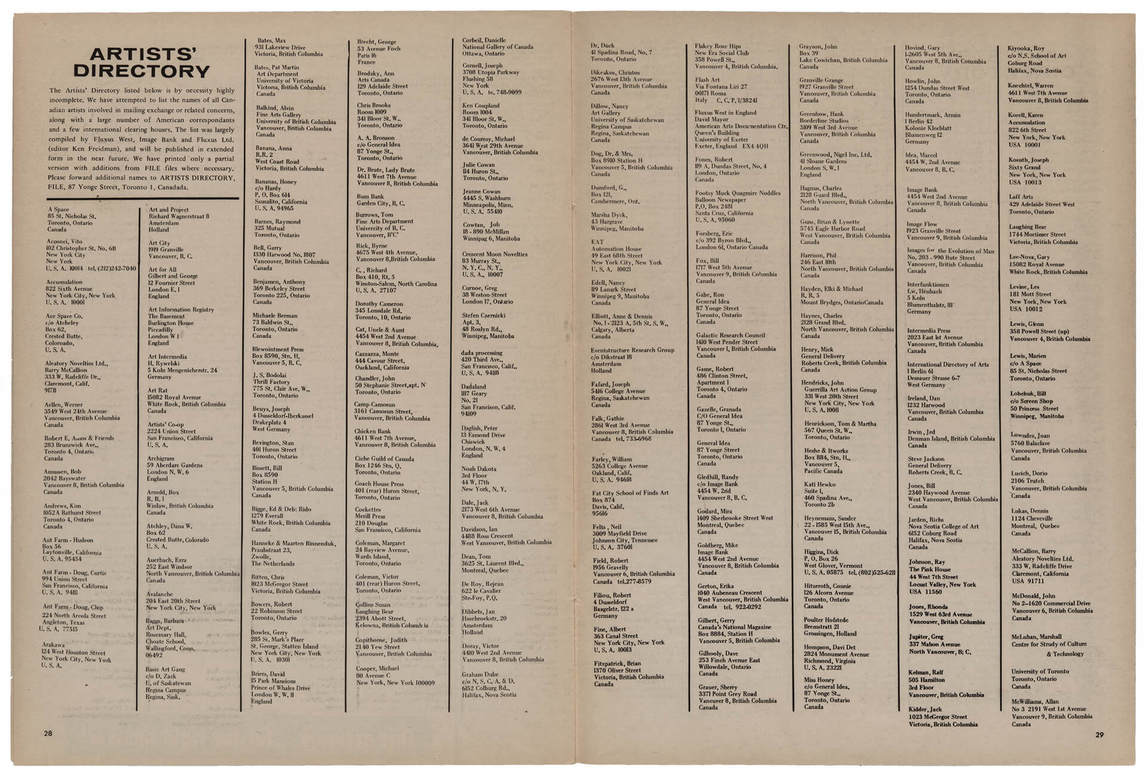

FILE is a renowned artist publication General Idea established in 1972. It ran for twenty-six issues before closing in 1989. They created FILE, described as “an alternative to the alternative press,” in order to connect with similar artists and advance common interests. AA Bronson explained, “The original purpose was to try and make a sort of cross-Canada network of artists. Because there was no outlet for the kinds of artists we were interested in, and we were aware that there were many people that we just didn’t even know existed.”

In its early years, FILE helped to build the Canadian art scene by providing a venue for the dissemination of artists’ projects and by publishing artist directories, which connected artists across Canada and the world. In the mid-1970s, FILE began to focus more closely on General Idea’s projects and interests, but still helped to connect communities, reaching artists in North America, Europe, and Japan. Notable early subscribers were Andy Warhol (1928–1987) and Joseph Beuys (1921–1986).

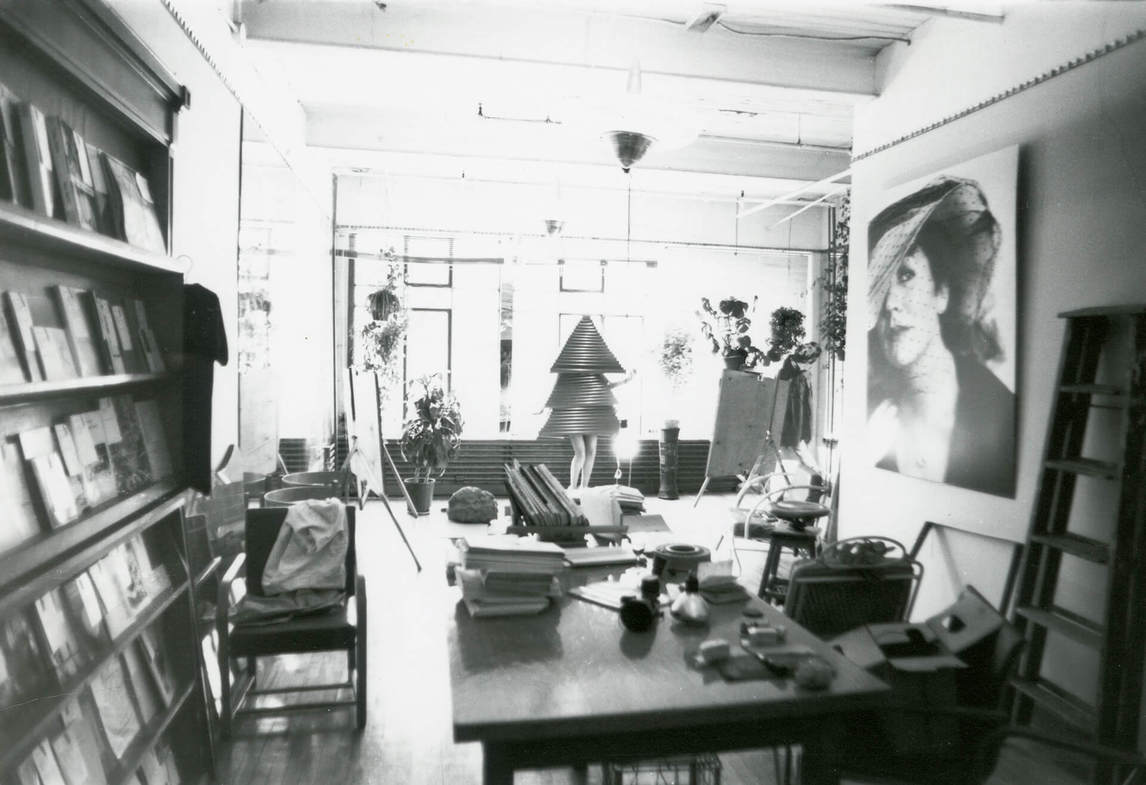

Art Metropole is an artist-run centre founded by General Idea that continues to operate in Toronto. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, numerous artist-run centres began to emerge in Canada as a parallel structure to the existing museum system. Initiated and managed by artists, many of these organizations were supported by the Canada Council. These not-for-profit spaces offered an alternative to the existing art venues in Canada. As Bronson notes in his “The Humiliation of the Bureaucrat” essay, museums provided inadequate representation of Canadian artists. There was a small number of isolated commercial galleries in Canada, with scant communication between them and no art fairs or any other signs of a developed commercial system. Artist-run centres provided a means of artist-led self-determination and a key source of support for experimental projects such as video works, performance art, and conceptual art, as well as exhibiting more conventional art forms. General Idea was active in this burgeoning artist-run centre scene, which included Intermedia in Vancouver. In Toronto the group exhibited entries from The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1971, at A Space, an artist-run centre founded in 1971.

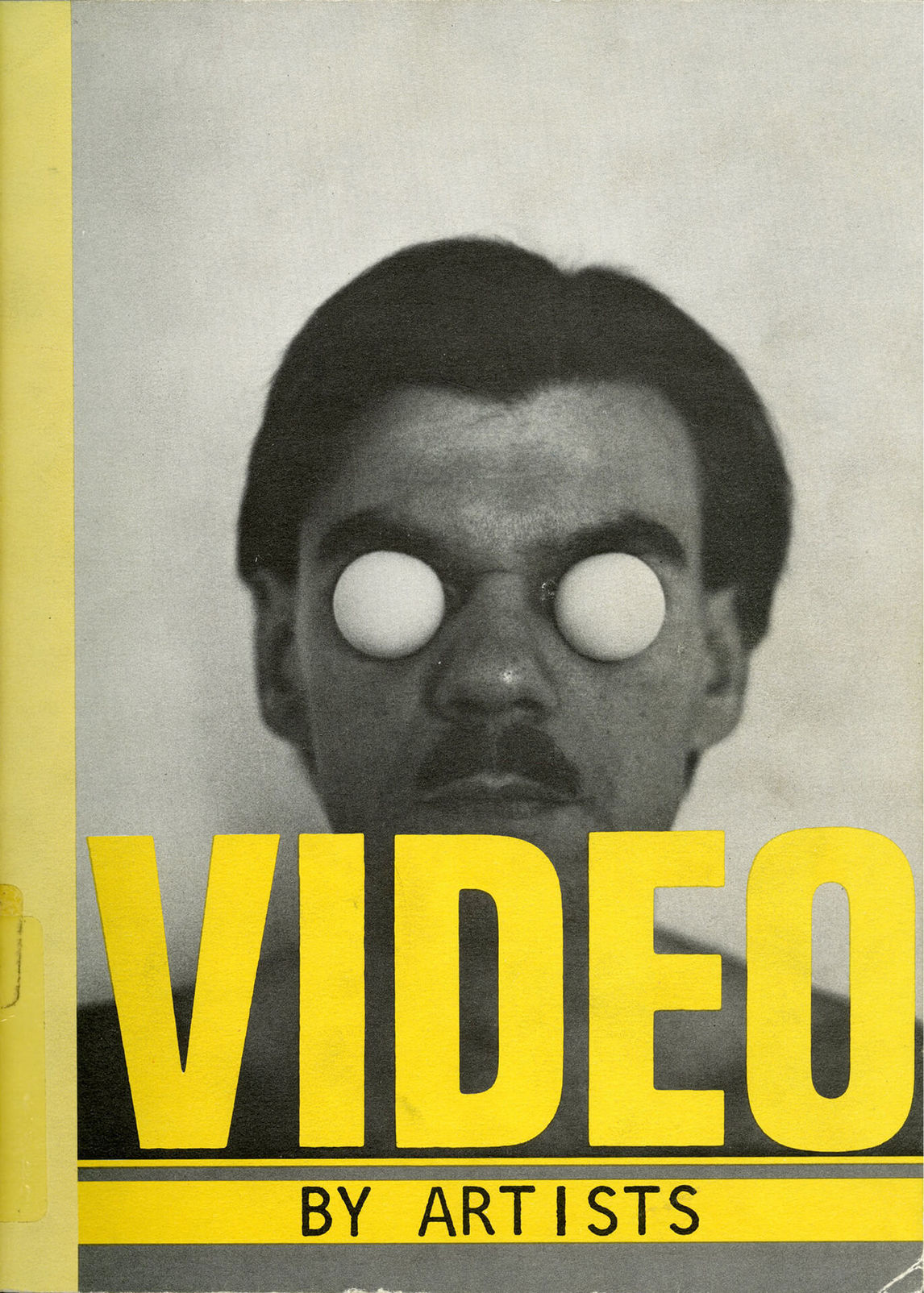

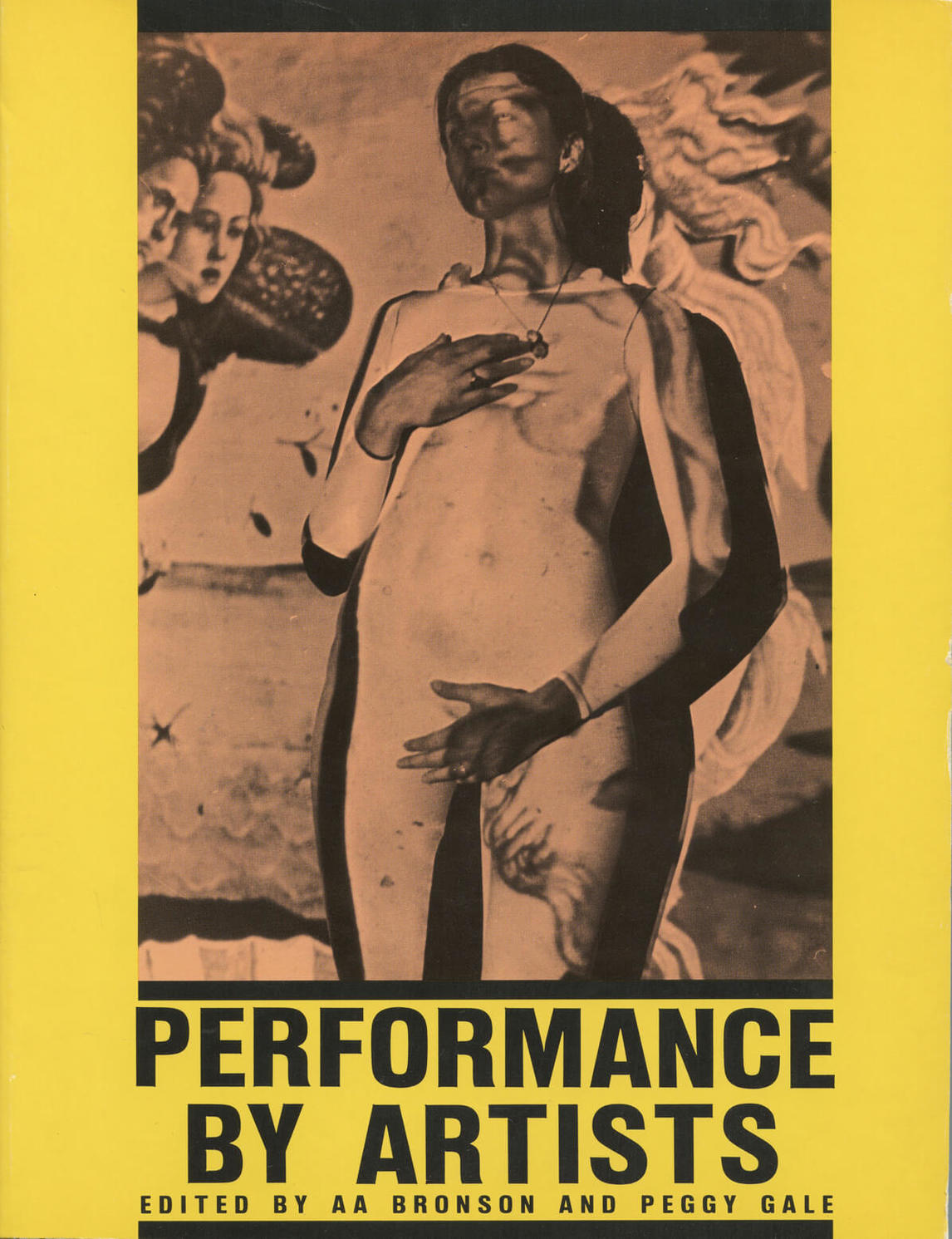

General Idea established Art Metropole in 1974. The organization’s mandate is to serve as a “collection agency devoted to the documentation, archiving and distribution of all the images.” This breadth is the strength of the institution, which distributes artists’ books, videos, audio works, posters, multiples, T-shirts, and more. Art Metropole also disseminated writing about new media and other art forms, for example in their “by artists” series of publications, which includes Video by Artists (1976), Performance by Artists (1979), Books by Artists (1981), Museums by Artists (1983), and Sound by Artists (1990).

General Idea founded Art Metropole in part due to the amount of mail art and ephemera they were collecting through FILE. In fact, Art Metropole was conceived of as an artwork—specifically, the archive and the museum shop for The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion. Felix Partz noted the importance of the organization to the group, explaining, “The actual structure and function of it, is an integral part of our work, of our overall project.”

Through FILE and Art Metropole, General Idea contributed significantly to the “connective tissue” of the Canadian art scene, developing the national artistic landscape and providing a means for artists—domestically and abroad—to connect to one another and to share work. Noting the importance of publications, organizations, and artist-run centres in the 1970s as a means for artists to coalesce into a scene, Bronson writes, “Working together, and working sometimes not together we laboured to structure, or rather to untangle from the messy post-Sixties spaghetti of our minds, artist-run galleries, artists’ video, and artist-run magazines. And that allowed us to allow ourselves to see ourselves as an art scene. And we did.”

Commerce and Consumption

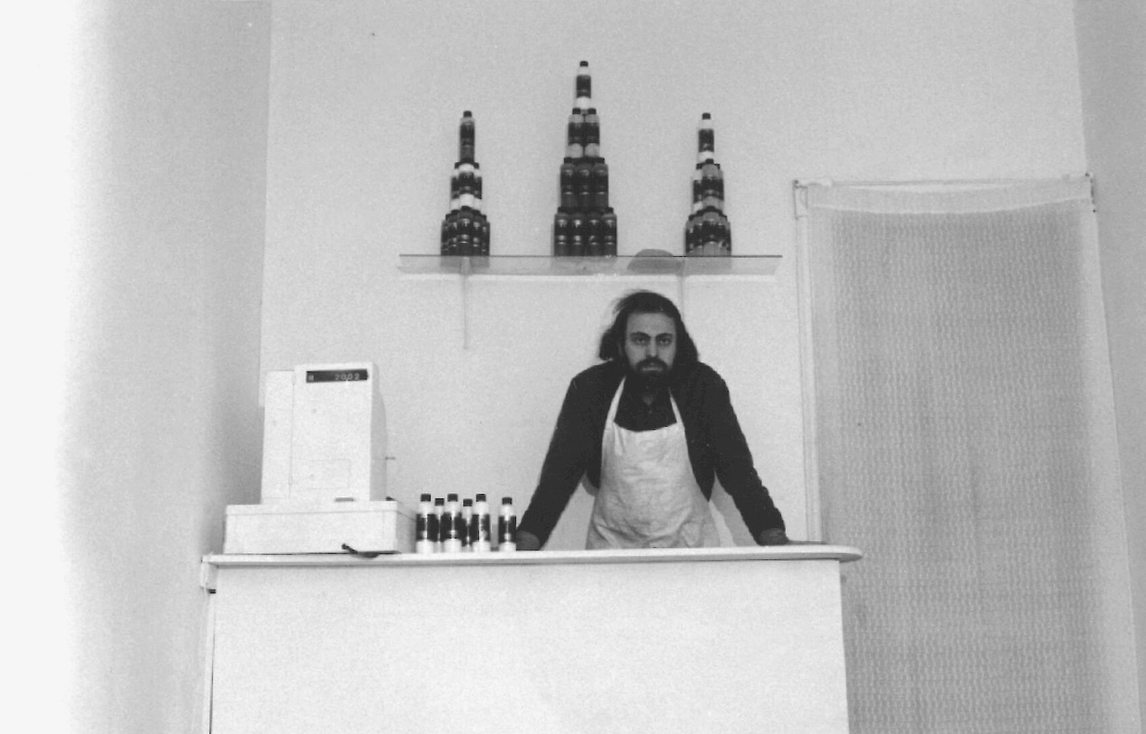

General Idea addressed consumption and commerce in diverse ways throughout their twenty-five-year collaboration. Early in their career, when they lived at 78 Gerrard Street West in Toronto, the group used the large front window of their home (a former storefront) to stage a rotating series of faux shops that subverted the store format, exhibiting all manner of found materials. The early shop window displays by General Idea played with viewers’ expectations: during the initial few projects the door to the house was always locked and a sign perpetually advised prospective customers that the shopkeeper would be back in five minutes. General Idea’s first use of the boutique format was The Belly Store, 1969, a collaboration with John Neon (b. 1944), where Zontal stood behind a counter and sold the multiple George Saia’s Belly Food, 1969, which was displayed in pyramids, like canned goods.

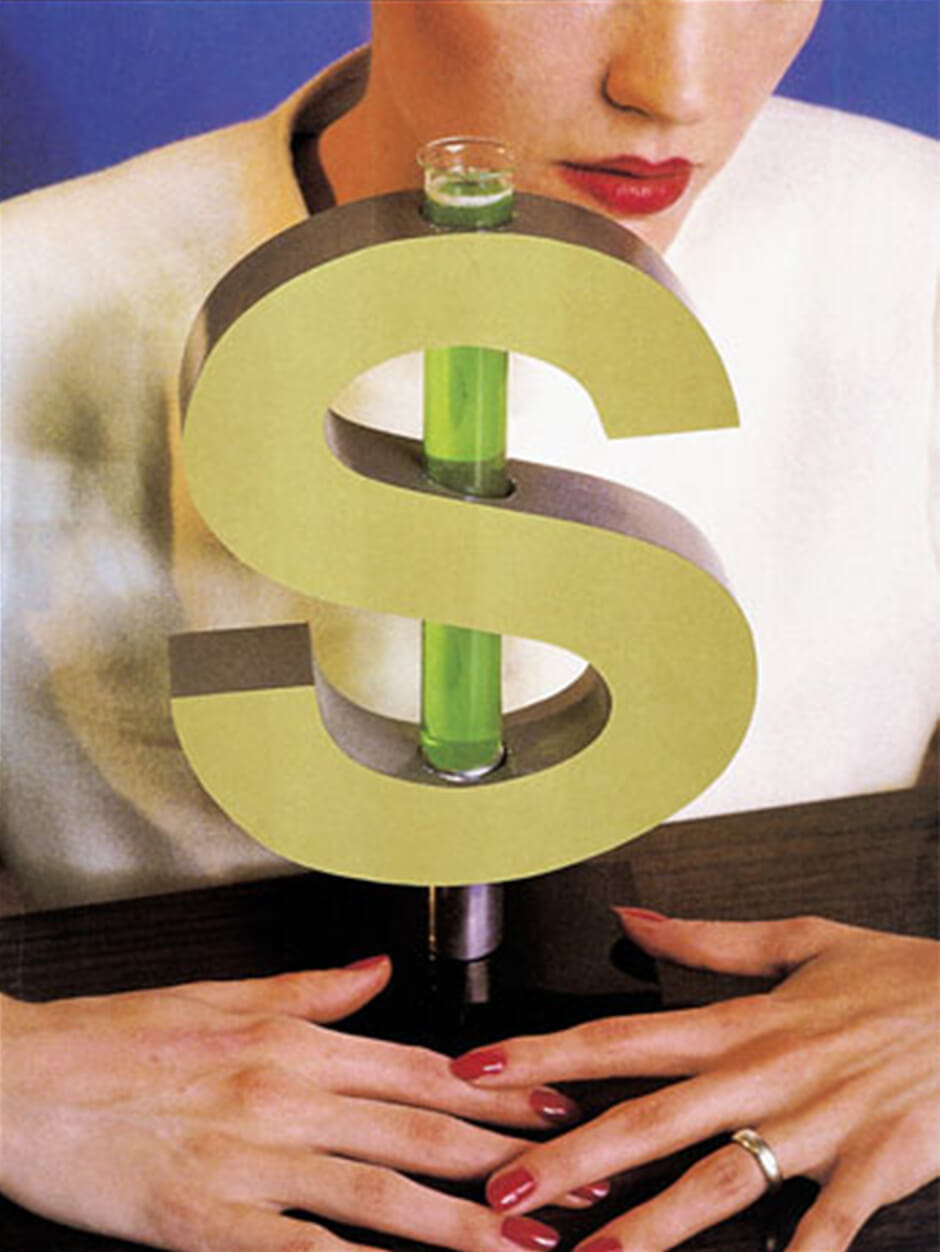

Later projects focused on commerce in relation to the art world, such as Test Tube, 1979, a video tackling commodification and the artist’s role within such systems. Test Tube, like other General Idea endeavours, gave rise to related works in other media. In this case, as AA Bronson explained, “the making of the video became the mechanism whereby we created all these props for the video and then produced them as multiples.”

General Idea also played with the notion of commerce and art by creating boutiques designed to function as retail sites within gallery and museum spaces. These derived from the artists’ consideration of the art world: “We were observing the beginnings of the blockbuster and the way that the museums were involving themselves with the world of money and marketing,” Bronson said. The Boutique from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, 1980, for instance, was a store counter made of galvanized metal and shaped like a three-dimensional dollar sign. The Boutiquesold a range of multiples by General Idea. These multiples included objects featured in Test Tube, such as Magic Palette, 1980, a metal tray shaped as a painter’s palette accompanied by six aluminum cups. Magic Palette was disseminated along with a softcover book, The Getting into the Spirits Cocktail Book from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion.

¥en Boutique, 1991, was another example of General Idea’s engagement with consumption. Its creation corresponded with the rising economic dominance of Japan at the time. The ¥en Boutique is a play on the shop format. The kiosk (which sporadically offered multiples for sale) was created by the group for museum display. The boutique format continued to hold interest for the group in the 1990s. The final boutique General Idea created was Boutique Coeurs volants, 1994/2001.

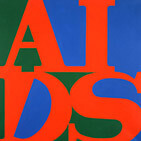

HIV/AIDS Activism

General Idea made a profound contribution to the discourse on HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This turn in their art occurred in 1987, when they created a painting for a fundraiser for the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). In AIDS, 1987, the artists appropriated American artist Robert Indiana’s (b. 1928) painting LOVE, 1966, replacing the word “LOVE” with the name of the new disease. The ironic appropriation of Indiana’s work was, AA Bronson later noted, in “bad taste. There was no doubt about that.” At the time, other artists were addressing the disease didactically in their work, in contrast to the more ambiguous statement General Idea made with AIDS.

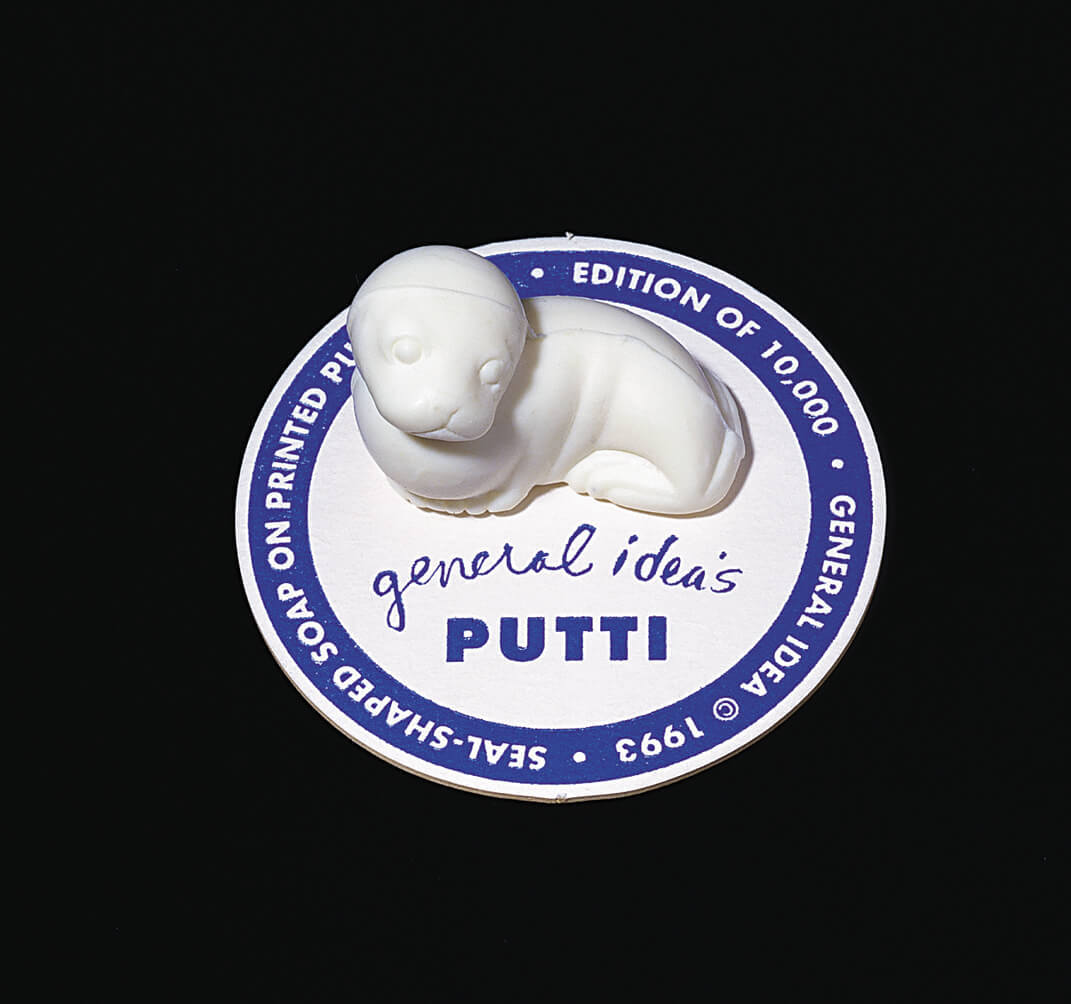

Despite the initial reaction to the work, General Idea went on to create a series of projects around their AIDS logo, producing these in diverse media, from posters to stamps to rings. They advanced this logo to raise awareness about and combat the stigma and misinformation surrounding AIDS. Bronson stated, “Part of the hook of it for us was the fact that it involved so many issues, not only health issues, which were especially acute in the U.S., but also issues of copyright and consumerism.” The artists also continued to raise funds for AIDS charities through initiatives such as General Idea’s Putti, 1993, a large-scale installation created from a commercially available seal pup–shaped hand soap placed on a beer coaster. Ten thousand of the soaps were assembled to create a gallery installation and were available for viewers to take, with the suggestion to leave a $10 donation for a local AIDS charity.

The significance of General Idea’s activism cannot be understated. At the time AIDS was a taboo topic surrounded by fear. Speaking to the climate of the era, artist and writer John Miller explained, “In 1987 especially, identifying oneself as HIV-positive differed from coming out. You could lose your job and your friends. Others still might want to quarantine you. Even obituaries skirted all mention of the disease.”

In the late 1980s General Idea’s AIDS work took on personal significance. One of the group’s closest friends (who helped in producing Going thru the Motions, 1975–76, and Test Tube, 1979) died of AIDS-related causes in 1987 in New York. The group served as primary caretakers for the last weeks of their friend’s life. Partz and Zontal were diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1989 and 1990, respectively. Both artists publicly disclosed their status and, until their deaths in 1994, General Idea continued to create poignant and engaging artwork addressing AIDS.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements