The evolution of Gathie Falk’s singular style is directed by her remarkable facility with a variety of artistic languages—painting, ceramics, performance, and installation—and a deep belief in the importance of the ordinary. Her painterly and compositional prowess, which she developed from the early stages of her artistic practice under the influence of the emotive distortion of German Expressionism, has come to define the quality of her work. Always seeking to find the art of daily living, she embraces the imperfection, texture, and personal meaning contained in the handmade and is guided by content found in her observed world.

Painting Life

Falk considers the 1962 Still Life paintings of flowers, vases, jugs, plates of food, and other domestic elements—such as Still Life with UBC Jug and The Blue Still Life—to be the earliest works she produced independently of teachers. The paintings of this moment are notably Post-Impressionist in their subject matter, composition, and style. It is interesting that an artist so recognized for her work in ceramics, performance, and installation would be, at her core, a painter.

Falk tells a childhood story that suggests she had an eye for good drawing at a very young age. When she was three, she insisted that her mother draw a picture of a woman for her. Unimpressed with her mother’s initial attempt—a series of unarticulated vertical lines—young Falk coached her through the missing elements, asking for a head, arms, feet, and chickens to complete the scene. Her exasperated mother soon gave up, declaring, “That’s the last drawing I will ever make for you!” It was clear Falk would have to look beyond home to find artistic instruction.

She took drawing and painting classes on and off from childhood into her early thirties, though she was often interrupted by work and other obligations. While it was her ceramics teacher Glenn Lewis (b.1935) who helped to mobilize Falk’s professional career, she has described the lasting impact of her studies with painting instructor J.A.S. MacDonald (1921–2013), who taught primarily through giving assignments and then offering individual critique, and Roy Oxlade (1929–2014), a British artist with whom she studied painting in Burnaby Central Secondary School’s evening class program. She recalls that Oxlade forbade his students from using colour, insisting instead that they use a monochromatic palette to explore brushstroke, abstraction, and the successful depiction of three-dimensional form on a two-dimensional surface.

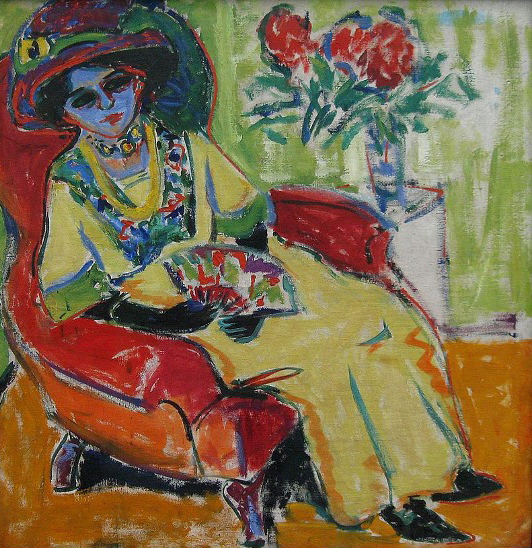

By the mid-1960s, Falk’s choice of subject matter had expanded beyond still-life compositions to include architectural spaces, figures, and landscapes. It is in works from these years, such as The Waitress, 1965, that Falk began to explore a more intense and emotionally driven style. “Despite the times, I was more interested in German Expressionism, which was figurative, than in American Abstract Expressionism,” she has said. She found that the distorted colour, scale, space, and forms of German Expressionism provided a suitable language for transferring what she saw in her mind’s eye to canvas.

Most of Falk’s work of this nascent period is in private collections or remains with the artist—this is perhaps why it is a lesser-known aspect of Falk’s oeuvre, or it may be under-acknowledged because it is so much easier to situate Falk’s early ceramic sculptures and performance art in the predominant practices of the time. While some of the artists Falk associated with through the Vancouver-based artist’s association Intermedia—Michael Morris (b.1942) and Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994), for instance—also had painting practices, their engagements with the medium are more in keeping with the predominant inclinations of the day, leaning as they do, in spite of their Conceptual art underpinnings, towards hard-edge, geometric abstraction.

In 1977, Falk travelled to Venice, Italy, with her friends Elizabeth Klassen and Tom Graff (active from the 1970s). From there, they visited the Scrovegni Chapel—also known as the Arena Chapel—in Padua, a building that is well known as the site of a remarkable fourteenth-century fresco cycle by Florentine artist Giotto (1266/67–1337) that depicts the life of the Virgin Mary, the life and Passion of Christ, and the life of Joachim. Venice, and Giotto’s frescoes, would remain in Falk’s subconscious, emerging in a range of ways some years later; the immediate effect, though, was a desire to return to painting. That year, Falk stopped remounting her performance artworks.

When she returned to painting, it was with a style that differed from her Post-Impressionist and German Expressionist inclinations of the 1960s. Take Border in Four Parts, 1977–78, for instance, an early project from her Border series, 1977–78, in which she created sequential paintings that honed in on just the edges of the gardens at her home and those of her neighbours. There is an emphasis on observation and intimacy, and the obvious point of reference in art history would be Impressionism, due to Falk’s use of the snapshot view and everyday subjects.

While her interest in working in series has long been established, in the Border paintings she introduces, with great subtlety, a shifting and unfolding of time and viewpoint that speaks to her personal and extended relationship with her garden, as well as with those of her neighbours. As art critic Robin Laurence has noted, “Falk was so pleased with the result that she repeated the photographic and painting process in West Border in Five Parts, and then in Lawn in Three Parts.”

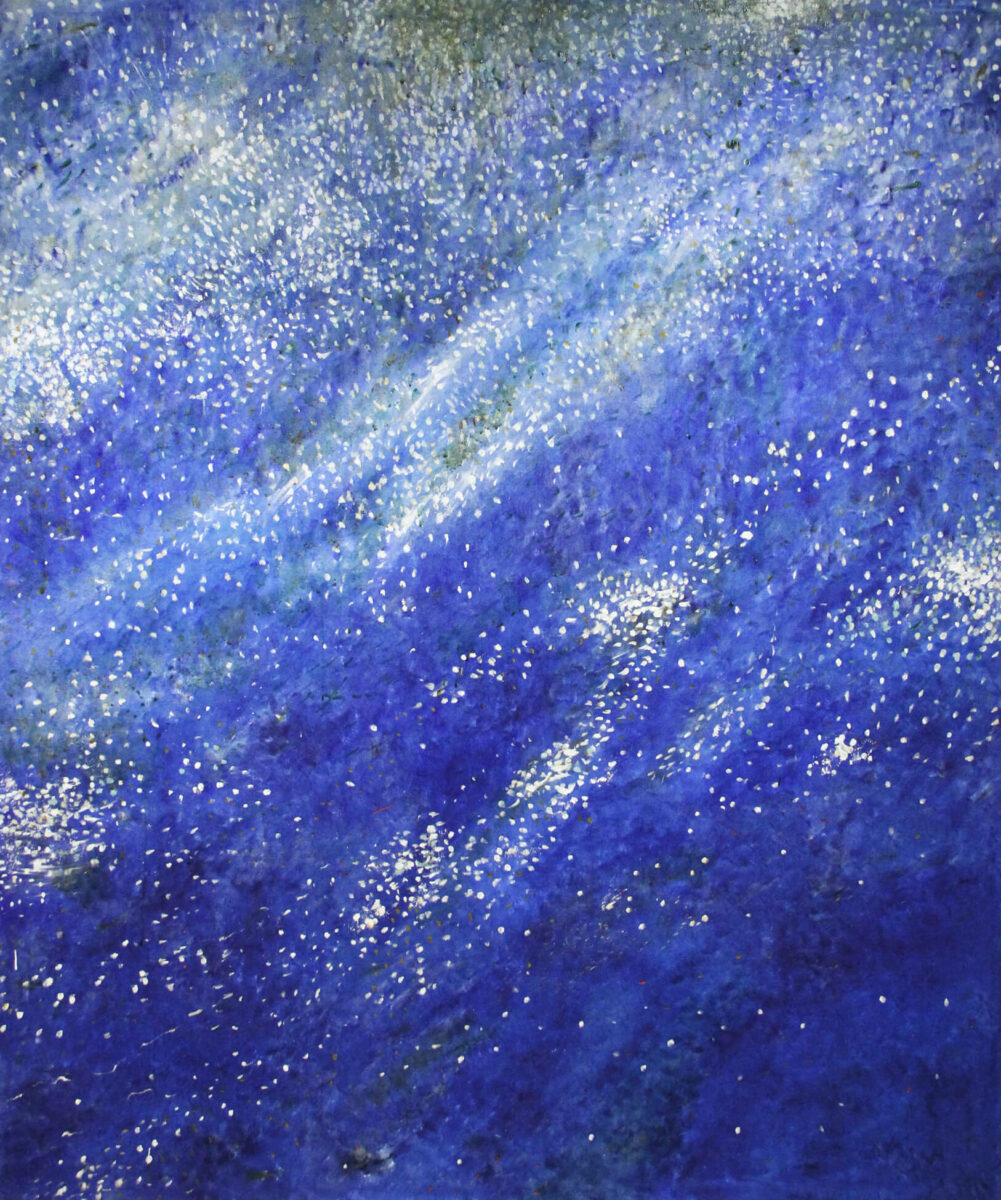

Falk’s interest in still life has remained consistent across the span of her painting practice. Her work looks at the ordinary through a new lens in order to see the commonplace anew. While the earliest series executed when Falk returned to painting in the late 1970s—the Border series; Night Skies, 1979–80; Pieces of Water, 1981–82; and Thermal Blankets, 1979–80—can be most clearly understood within the trajectory of the landscape genre, with the Theatre in B/W and Colour series, 1983–84, she for all intents and purposes returns to still life, using a pared-down selection of ingredients. Some are typical to the genre, such as fish, fruits, and flora; others are part of Falk’s unique personal language, such as streamers, bows, chairs, and light bulbs.

With the Theatre in B/W and Colour works, Falk employed a compositional structure that exploited her inclination toward repetition and the grid. A decade later, with Nice Tables, 1993–95, a series of triptychs, she continued her investigation of architectural, illusionistic, and pictorial space begun with the Development of the Plot works, 1991–92—surreal, theatrical compositions that feature repeated elements including a man in an overcoat, dogs, wooden chairs, flowers, disembodied arms, light bulbs, and a double staircase—but also dug into the potential of the still-life subject.

While each painting in the Nice Tables series uses the same basic format—a table on a patio between two planar posts and a wall—the items on and around the table change. The objects Falk selects are generally typical of the still-life genre—fruit, bowls, cups and saucers, vases of flowers, pitchers, trays—but they are combined and contextualized in a manner that emphasizes her penchant for the uncanny.

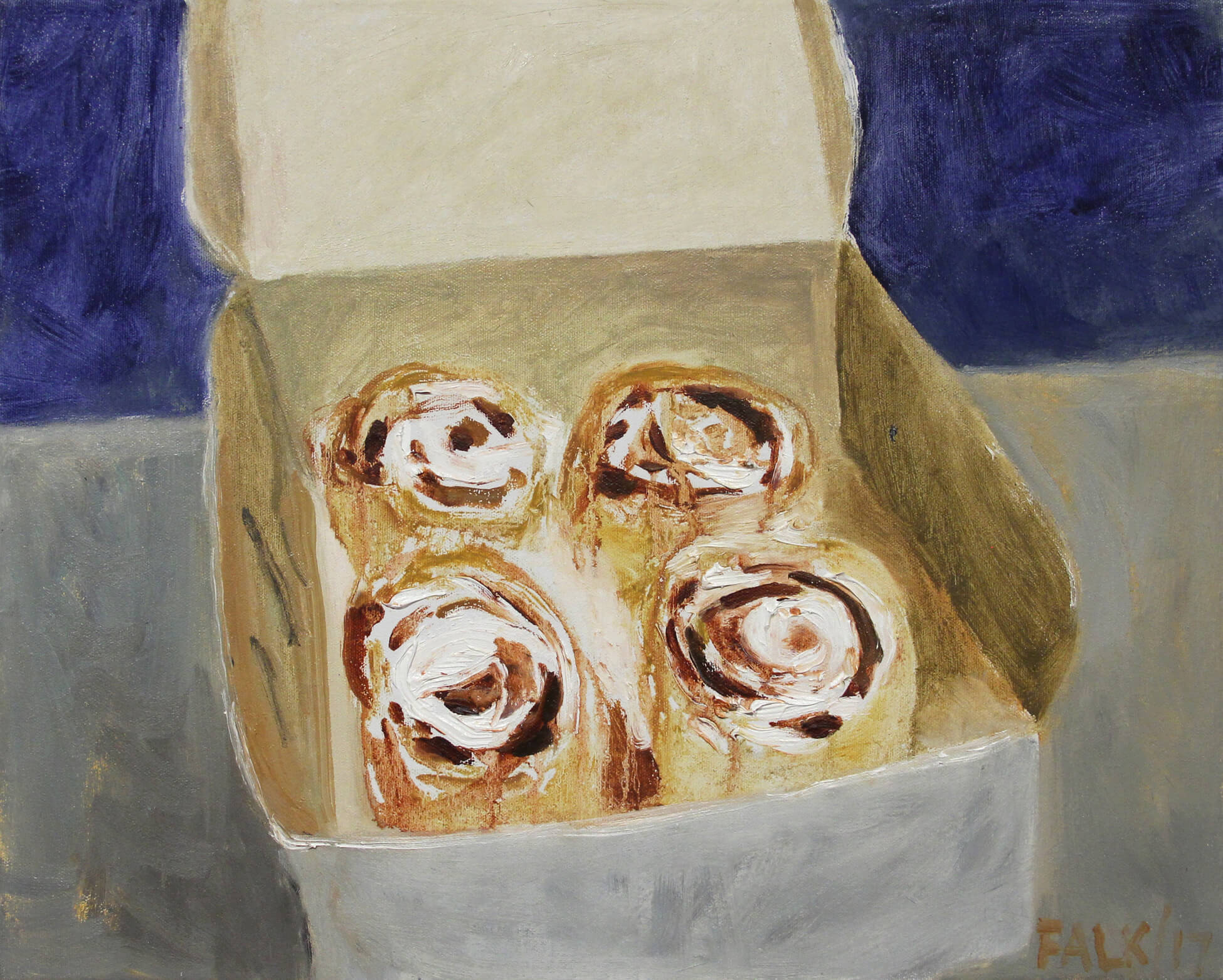

Since 2010, Falk has returned to still-life painting in full force; the scale of such works and the availability of the things she includes in these compositions are accessible to an artist in her tenth decade. In Falk’s case, this is not a withdrawal from making work that pushes her interests forward but rather a reinforcement, consolidation, and even augmentation of a direction long established in her practice.

Falk’s home and the objects in her daily life act as the source material for these new paintings. She has reconstructed intimate details from her own existence: a carefully set table with cake, coffee, and tea; a portrait of her painting work shirt hung on a simple, yellow wooden chair; laundry slowly drying on an outdoor washing line; and a perfectly presented box of delicious cinnamon buns. Through these paintings, Falk celebrates simple pleasures, elevating ordinary objects and appreciating the joy and love she feels for the things and people in her life.

Sensing Ceramics

Falk uses clay to create ceramic sculptures of everyday objects. In some cases she approaches her subjects as elemental and iconic, as with the stacks of apples and oranges in her Fruit Piles, 1967–70, and the cases of sneakers and boots in Single Right Men’s Shoes, 1972–73. In other instances she approaches the clay in a more painterly manner, creating more intricately conceived tableaux, such as Art School Teaching Aids, 1967–70—assemblages of objects inspired by different art historical moments—and Table Settings, 1971–74, and Picnics, 1976–77—Falk’s imaginative conceptions of fantastical indoor and outdoor repasts.

Falk’s execution of her ceramic works operates somewhere between the beautiful and the crude. Apples, oranges, boots, brogues, and even Chuck Taylor high tops achieve a certain kind of exquisiteness through Falk’s use of richly coloured glazes and ordered methods of presentation. However, she also appreciates the potential of clay to read as skin, holding in its surface pocks, wrinkles, and dimples, and it is in this emphasis on the potential of ceramic to read as unpolished that Falk finds her particular voice.

In the 1960s, when Falk embraced ceramic sculpture as a language of expression that would be central to her practice, there was significant activity happening around the genre in the Bay Area and Davis, California, where the ceramic movement was known as California Funk, and in Regina, Saskatchewan, with the Regina Clay movement. Interestingly, there was a Canadian artist who travelled between the two locales at the time, Marilyn Levine (1935–2005), who was known for making items of clothing, including shoes, out of clay. Levine’s work was included in the exhibition Ceramics ’69 at the Vancouver Art Gallery at a time when Falk was avidly engaged with that institution.

When Falk took up her study of pottery, her teacher at the University of British Columbia, Glenn Lewis, had deep roots in functional ceramics traceable to studios in the United Kingdom—he had trained at the famed studio of Bernard Leach (1887–1979) in St. Ives and with Canadian potter John Reeve (1929–2012) in Devonshire. Lewis was committed to training his students in a manner that emphasized the conceptual foundations of pottery and eliminated the barriers between art and craft. Over just a few years, Falk made an impressive move from producing paintings rooted in early twentieth-century traditions to creating conceptually driven ceramics on par with some of the most radical work in the medium.

Falk evades direct alignment with any school or movement, including Funk, yet she shares the belief in the elevated role of clay and her ceramic work demonstrates many of the other qualities of Funk, such as the inclination toward clay’s sculptural potential and emphasis on humour, engagement, autobiography, and found and everyday objects.

Falk’s clay objects are built by hand, or, in the case of the elements that comprise her Fruit Piles, are hand-thrown on the wheel and then closed, rolled, and formed to the desired shape. When she produced the components of 196 Apples, 1969–70, many of the apples turned orange, grey, or almost black instead of red in the firing process. Falk accepted this result and incorporated the discoloured apples into the pyramid. She felt that this imbued a greater strength to the piece, elevating it above the merely pretty and providing a better approximation of the realities of the world, where the beautiful and the ugly so often exist side by side.

That said, there is lusciousness to the surface treatment of her fruit and men’s shoes that is irresistible. In other ceramic series like Art School Teaching Aids, Table Settings, and Picnics, for instance, Falk used acrylic paint rather than glazes to colour the work so that she could maintain control over the surface effects. The outcomes of her decisions are ceramics that move beyond our material expectations of the language of pottery.

Composing Performance Art

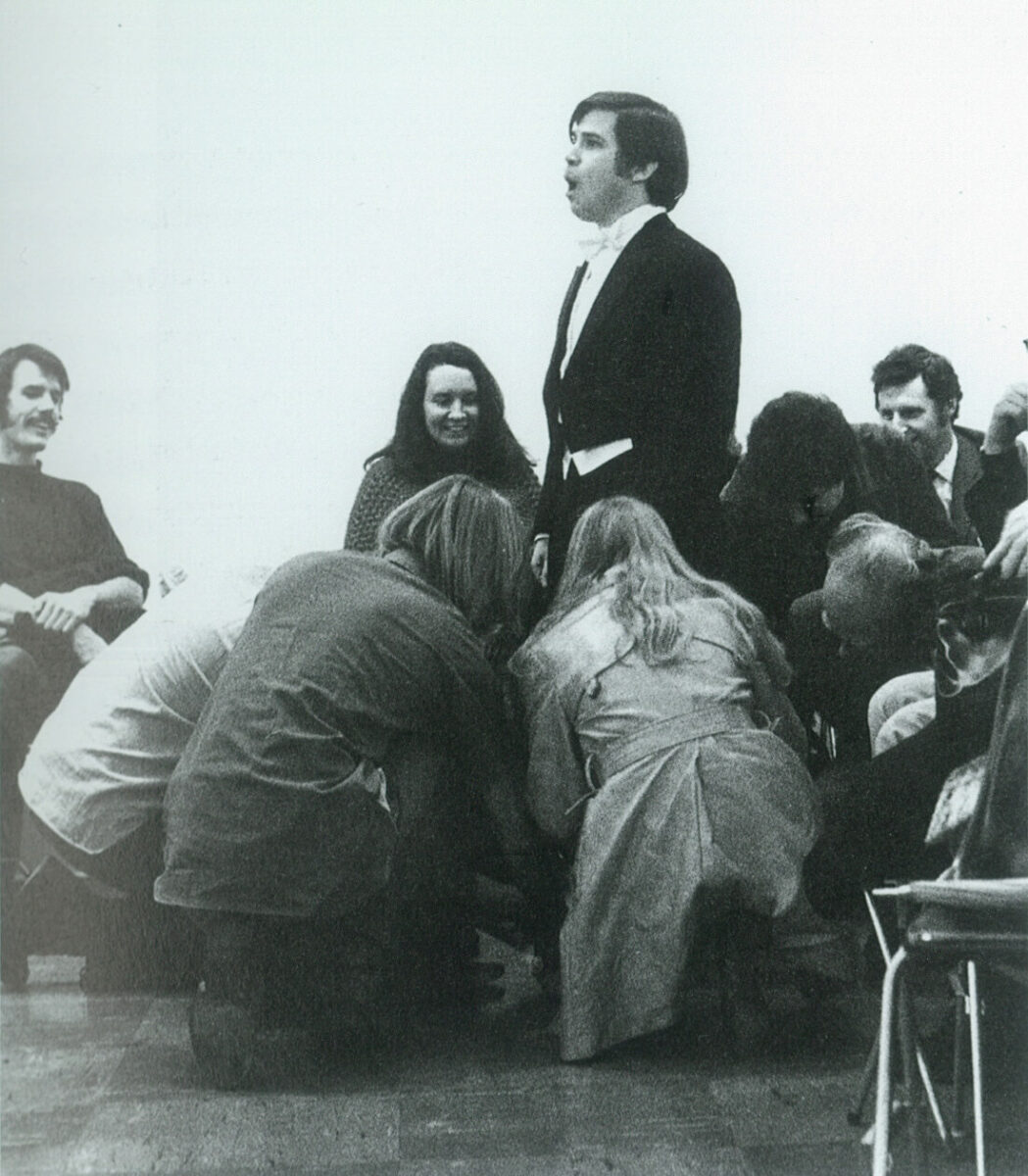

The period from 1968 to 1972, when Falk created her performance artworks, was early enough in her emergence as a visual artist that the memory of music—her first creative love—was still strong. She connected the influence of the American performance artists who visited Vancouver from New York’s Judson Dance Theater in the late 1960s—Deborah Hay (b.1941), Yvonne Rainer (b.1934), and Steve Paxton (b.1939), all of whom came from backgrounds in dance and choreography—to her early training in music.

Falk has noted that “To make a performance piece is to… choreograph, or compose, a work of art that has a beginning, an end and a middle, with, preferably, but not necessarily, a climax or several climaxes. Sometimes… the choreography is worked out like a fugue in music, with one event beginning close upon the heels of another and a third event intertwining with the first two. The analogy of music is apt. One of my works, Red Angel, is like a rondo with theme A followed by theme B, followed by theme A.”

Falk’s commitment to performance art was brief within the span of her lengthy career, and her activity in this realm might seem incongruous with the paintings and objects for which she is so well known. However, for her, it was another useful means to represent the images she saw in her imagination, and she is to be celebrated for creating some of the earliest works of performance art in Canada.

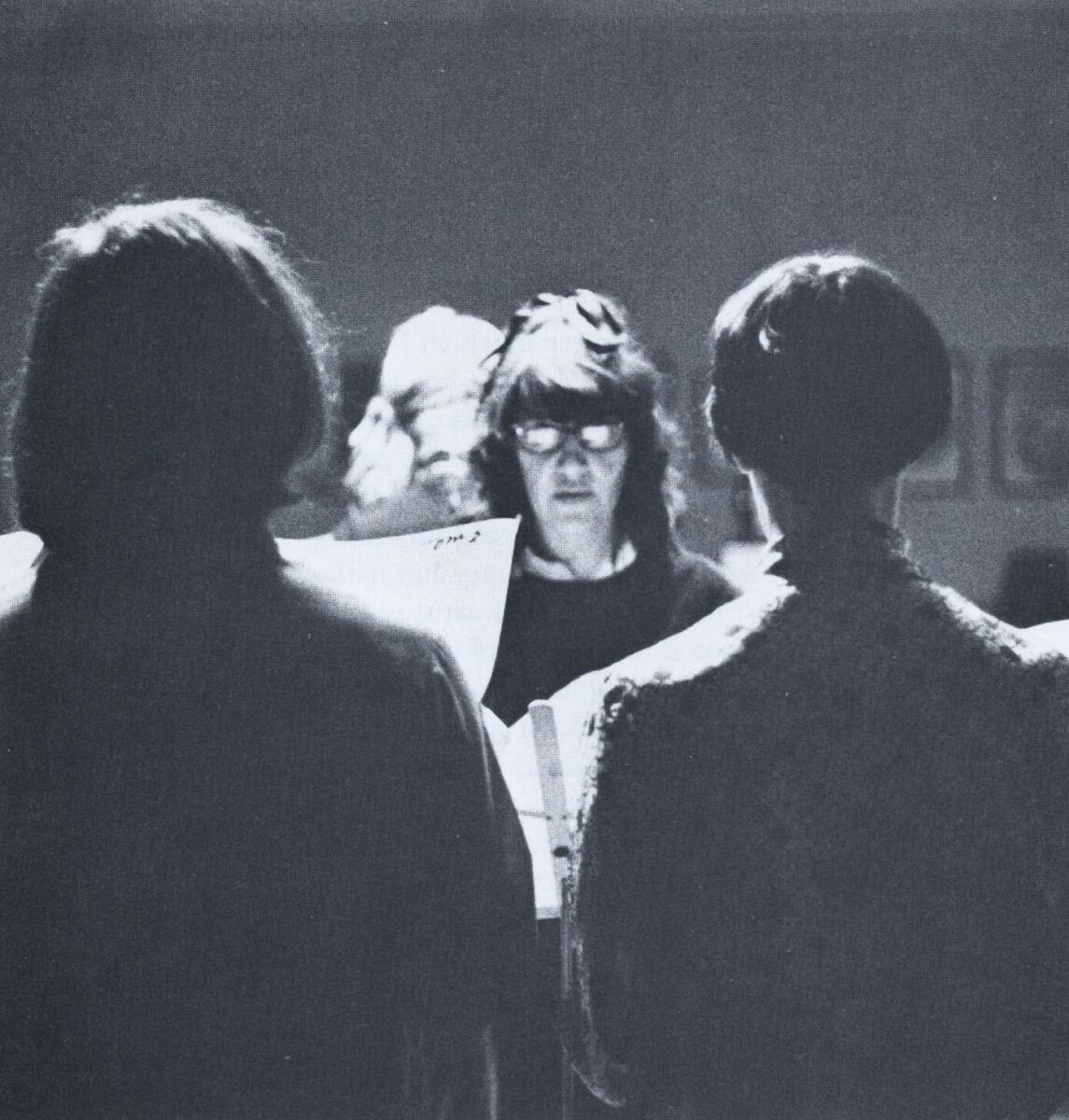

While performance art tends to be based on the premise that the work has to be experienced to be known, there is some quite remarkable documentation of Falk’s performances. Her friend and long-time collaborator Tom Graff produced a video of the ones that were mounted as part of Falk’s 1985 retrospective at the Vancouver Art Gallery, and his essay from that exhibition’s catalogue, “Notes, Anecdotes, and Thoughts on Gathie Falk’s Performance Art Work,” was reprinted in Caught in the Act: An Anthology of Performance Art by Canadian Women (2004).

The musical foundation of certain performances, such as the aforementioned Red Angel, is one recurring theme. Some of the works incorporate musical elements in a very direct way, at times in the form of taped recordings, such as the canary whistling “Danny Boy” in A Bird Is Known by His Feathers Alone, 1968, or the adagio by Georg Philipp Telemann and the finale from Götterdämmerung—the final piece in Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle—that bookend Cake Walk Rococo, 1971. There are other works in which Falk included live musical recital—she herself sings Johnny Cash’s “Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes” in the performance film Drink to Me Only, 1971, and in Ballet for Bass-Baritone, 1971, a collaboration with Graff, Graff sings “Allegro alla breve” from Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella.

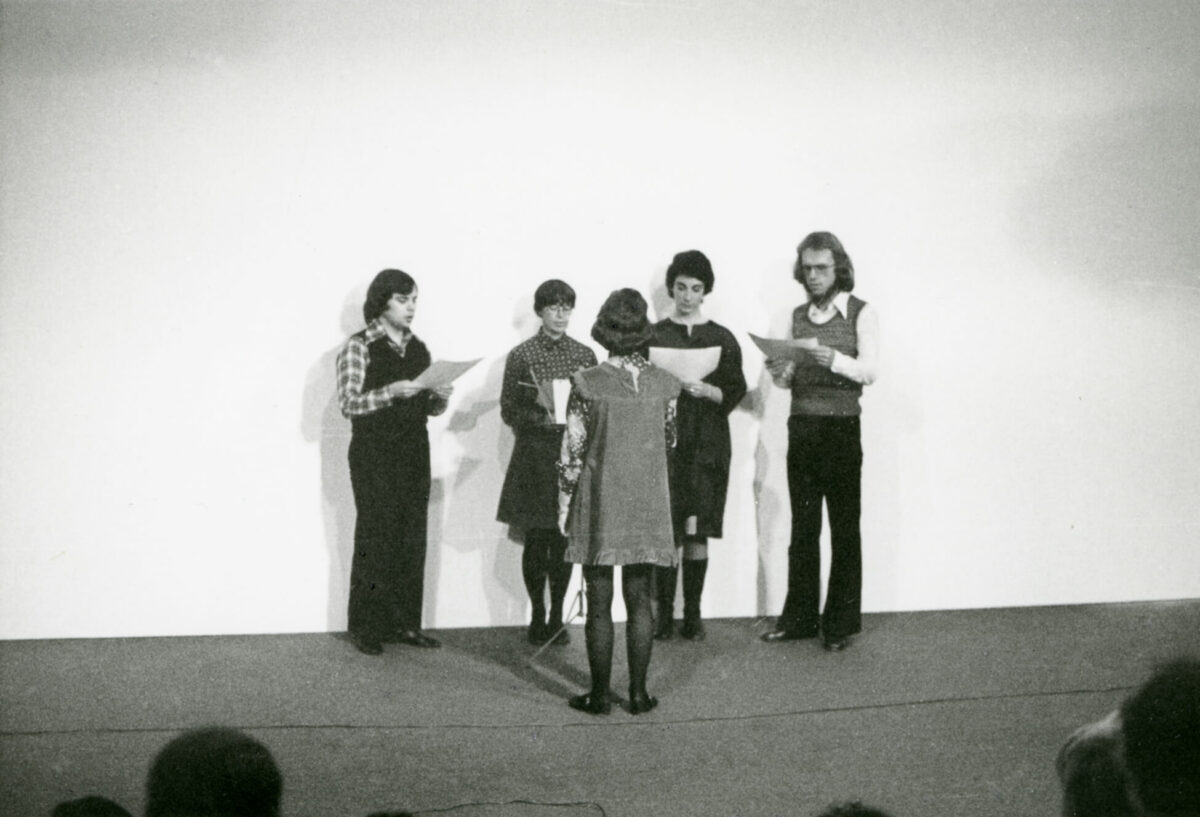

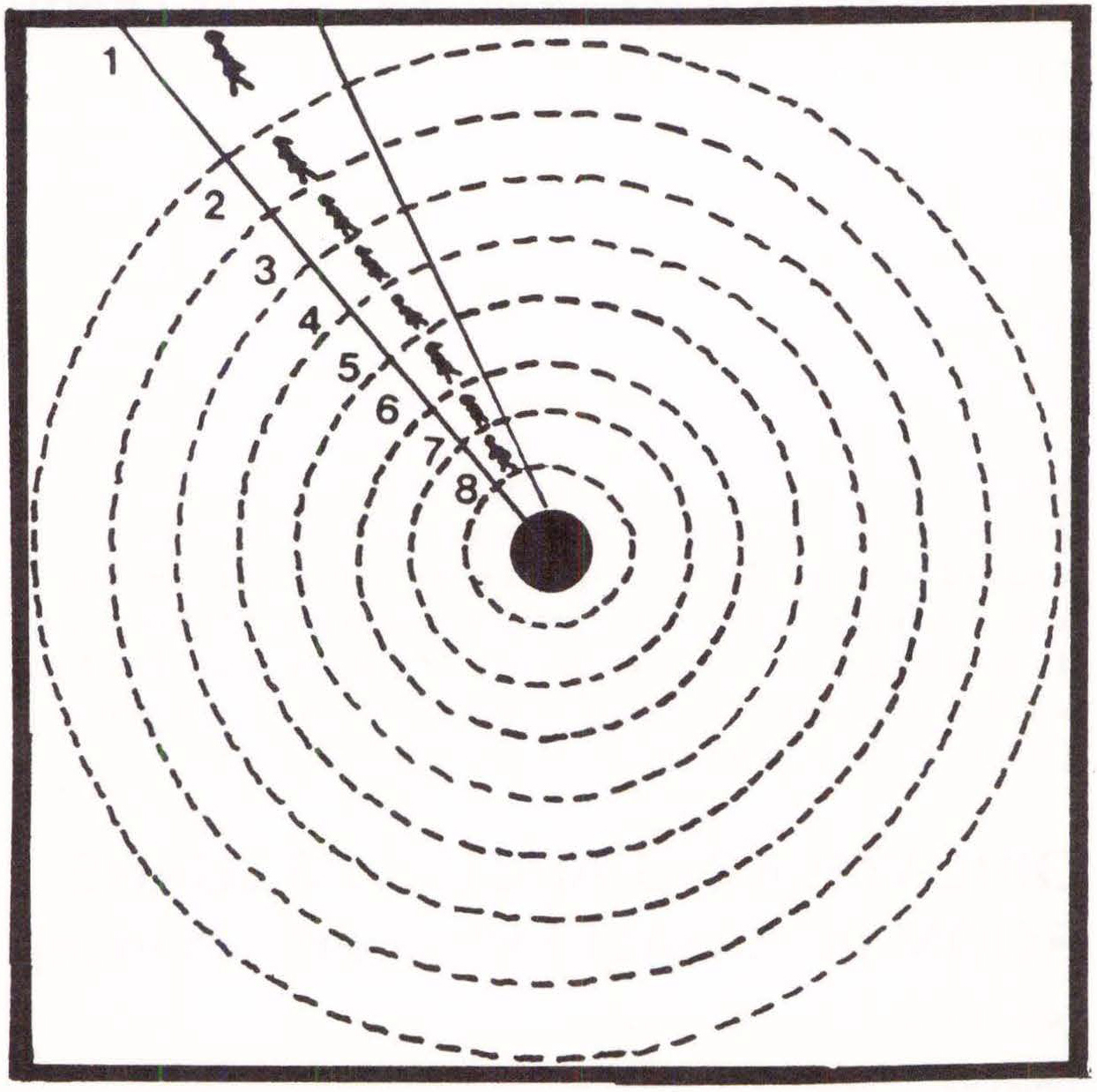

Even when Falk’s performances do not include music per se, they often include musically inspired structures. Many of her pieces are documented in scores that were included in a 1982 Capilano Review feature on her work, an invaluable resource that also includes excerpts from critical reviews and commentary from the artist. While Falk typically referred to her creations as Theatre Art Works, that they are documented as scores rather than scripts is indicative of their origins in the principles of the Judson Dance Theater artists. She had also, of course, been deeply committed to the strong Mennonite choral tradition, and the chorus structure recurs in her performances.

In Girl Walking Around Square Room in a Gallery, 1969, the title aptly describes the action of the film version of the work: it is presented with the projector mounted on a turntable at the centre of the room so that the walking girl is projected onto all of the walls. In the live version of the work, a chorus of live performers accompany the projected girl, walking with her as she moves.

In the interview conducted with Falk for the Capilano Review feature, co-author Aaron Steele asked, “If [you say that] theatre art is time-space collage sculpture, what part does the audience play?” Falk responded, “It plays the same role as an audience for sculpture or painting, except they can see it only once.” A work such as Girl Walking Around Square Room in a Gallery suggests that at times Falk enjoyed taking advantage of the opportunity to force a more active response from her viewers.

Of course, there was the work actually entitled Chorus, 1972, a performance that includes a group of twelve people led through a fugue-like chant—“name, age, sex, racial origin”—by a conductor, which they sing in four parts for four voices. It is worth noting here that Mennonite hymns are traditionally performed in four-part harmony.

While there is no music included in the work Drill, 1970, which was first presented at the University of British Columbia’s Fine Arts Gallery (now the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery), the concluding action involves the many performers lining up in two rows “as though they were a chorus,” according to Ann Rosenberg. “The leader of the chorus shines their shoes while the chorus members at various times and in various ways say what they had for dinner.”

Evoking Environments

The imagery from Falk’s performances would bleed into her other work. Additionally, while she produced no more performance art after 1972, and stopped performing altogether by 1977, she continued to explore composing images in space through the creation of installations—or environments—that extended her interest in making art that was experiential as well as visual.

This thread in her oeuvre can be traced back to the pivotal piece Home Environment, 1968. While that early project took as its foundation a familiar locale—a domestic space—in installation work produced after her engagement with performance, there emerged an approach that was akin to much of the performance work, which Falk has said could be described as “time-space collage sculpture.”

This assertion of a compound artistic genre is just as applicable to works such as 150 Cabbages, 1978, which combined ceramic cabbages—meticulously constructed from individual ceramic leaves—suspended from kitchen twine, a bed of sand covering the entire gallery floor, and a mirrored dresser with drawers full of facial tissues that somehow evoke ideas of human presence and the passage of time. 150 Cabbages is an installation that has something else in common with performance—only those who saw its initial presentation at Artcore, Vancouver, got to experience the full work, as when it was dismantled, the cabbages were sold individually. It has only been recreated and remounted in very reduced form.

Prior to 150 Cabbages, Falk had spent an extended period of time creating Herd I and Herd II, 1974–75 , two distinct installations each composed of twenty-four painted plywood horses suspended above the ground. The manner in which images would occupy Falk’s mind for extended periods before inspiring a particular work is well documented with this piece. A coin-operated mechanical horse had been included in a work by Graff called Canada Family Album, 1973. Falk envisioned a herd of them at the time of Graff’s performance, and she decided to create them as plywood cut-outs, suspended like the clouds in Low Clouds, 1972.

Falk worked with an assistant, Jeremy Wilkins, who sealed and filled the plywood forms and applied the white ground, but Falk cut out every single horse herself and painted each one on both sides to be unique and individual within the crowd. Each herd was to be hung in its own separate room, suspended on invisible wire about 30 centimetres from the ground with enough room for viewers to walk around them. As Ann Rosenberg wrote, Falk “probably could not have anticipated the electrifying effect the white herd, especially, produces in the viewer. It is like encountering an otherworldly stampede.… Slight air currents cause some herd members to tremble at all times, increasing the nervous, energized quality of an apparition of 24 animals caught, momentarily, in the act of flying from the room.”

It has been some time since Falk, who is now in her nineties, could meet the physical demands of the production of works such as Herd I and Herd II, 1974–75, or the public artworks Veneration of the White Collar Worker #1 and Veneration of the White Collar Worker #2, 1971–73, the two wall-spanning ceramic murals created for the Department of External Affairs building in Ottawa, and Beautiful British Columbia Multiple Purpose Thermal Blanket, 1979, the enormous, quilt-like sculpted painting commissioned by the B.C. Central Credit Union in Vancouver. Although these latter works are not encompassing in their three-dimensionality, as they are wall mounted, they nevertheless possess a monumentality and difficulty of production that is similar to the installation work.

It is no longer feasible for Falk to manage large and multiple components of an installation. However, it is interesting to examine how in recent years, in order to create her gallery shows—such as Heavenly Bodies, 2005; Dreaming of Flying, 2007; and The Things in My Head, 2015, all at Equinox Gallery in Vancouver—she has taken to pulling together works from across time and projects to be put together in new configurations, creating evocative environments within the gallery space.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements