One of Canada’s most acclaimed living artists, Gathie Falk (b.1928) imbues ordinary objects and everyday rituals with qualities of the sublime. From humble beginnings in Manitoba, she has become a leading figure in Vancouver’s artistic community and received international recognition for her painting and ceramic sculpture, as well as her pioneering work in installation and performance. Now in her nineties, Falk continues to produce and exhibit regularly, enjoying critical and popular success for work that has never veered from her playful, purposeful, and unapologetically personal vision.

Childhood and Adolescence

Although Gathie Falk’s itinerant early years were marked by loss and poverty, they were also buoyed by art, community, and religious faith. She was born on January 31, 1928, in Alexander, a small town in Treaty 2 territory, just west of Brandon in southern Manitoba. Her parents, Cornelius and Agatha Falk, were German-speaking Mennonites who had immigrated to Canada in 1926 with their two sons to escape Communist persecution in Russia. Just three years after they left, many of the Mennonites who had stayed behind were either exiled to Siberia or killed.

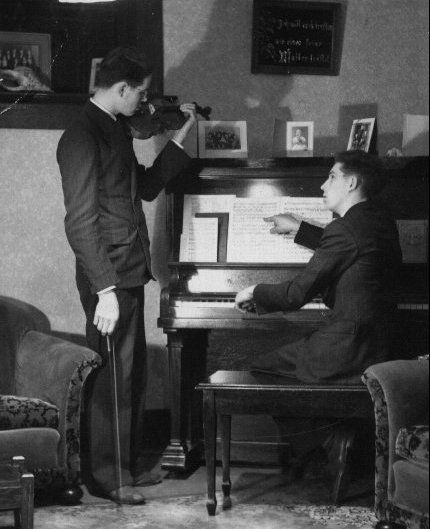

Falk’s family had owned property and a business in Russia, and land acquisition would have been easy in the Prairies due to an agreement made between the Canadian government and leaders of the Mennonite community in Russia. In 1872, the year after Treaties 1 and 2 were signed, the federal government passed the Dominion Lands Act, which was a law aimed at encouraging agricultural settlement of the Prairies. Cornelius Falk, however, wittingly chose to forgo the opportunity to own land in Canada. A gifted musician who played the violin, sang, and was a choral director, he was asked to teach music at a college in the United States, but he refused that too. Instead, he chose to labour for other farmers in his new homeland.

Cornelius Falk’s decision to pursue a less materialistic and more spiritual existence resulted in extreme hardship for his family when he died of pneumonia in November 1928, less than a year after his daughter’s birth and barely two years after arriving in Canada. After Falk’s father died, her childhood became somewhat nomadic; her mother, now reliant on the support of the community in order to keep her family housed, clothed, and fed, moved Gathie and her older brothers, Jack and Gordon, from one Mennonite community to another throughout Manitoba, Ontario, and Saskatchewan, seeking support wherever she could find it.

Growing up poor meant being resourceful and learning how to make new things out of the old. While the household Falk grew up in wasn’t necessarily artistic, it was certainly crafty and creative. In her 2018 memoir, Apples, etc., Falk recounts how she made her first doll’s dresses when she was still a toddler, using scissors, cloth, and string. She also describes begging her mother and brother to draw pictures of human forms for her and having a good enough critical eye—despite her tender age—to recognize the failures of their artistic attempts.

By the time Falk was a teenager, her family was living in Winnipeg. Her brothers had left school to help support the family. She was a good student with evident creative talent, and at age thirteen, her grammar school teacher recommended her for Saturday morning art classes. Falk recalls taking the bus downtown to “a civic building on Vaughan Street that had a museum in the basement [the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature], an auditorium on the main floor, and an art gallery on the top floor [the Winnipeg Museum of Fine Arts, now the Winnipeg Art Gallery].”

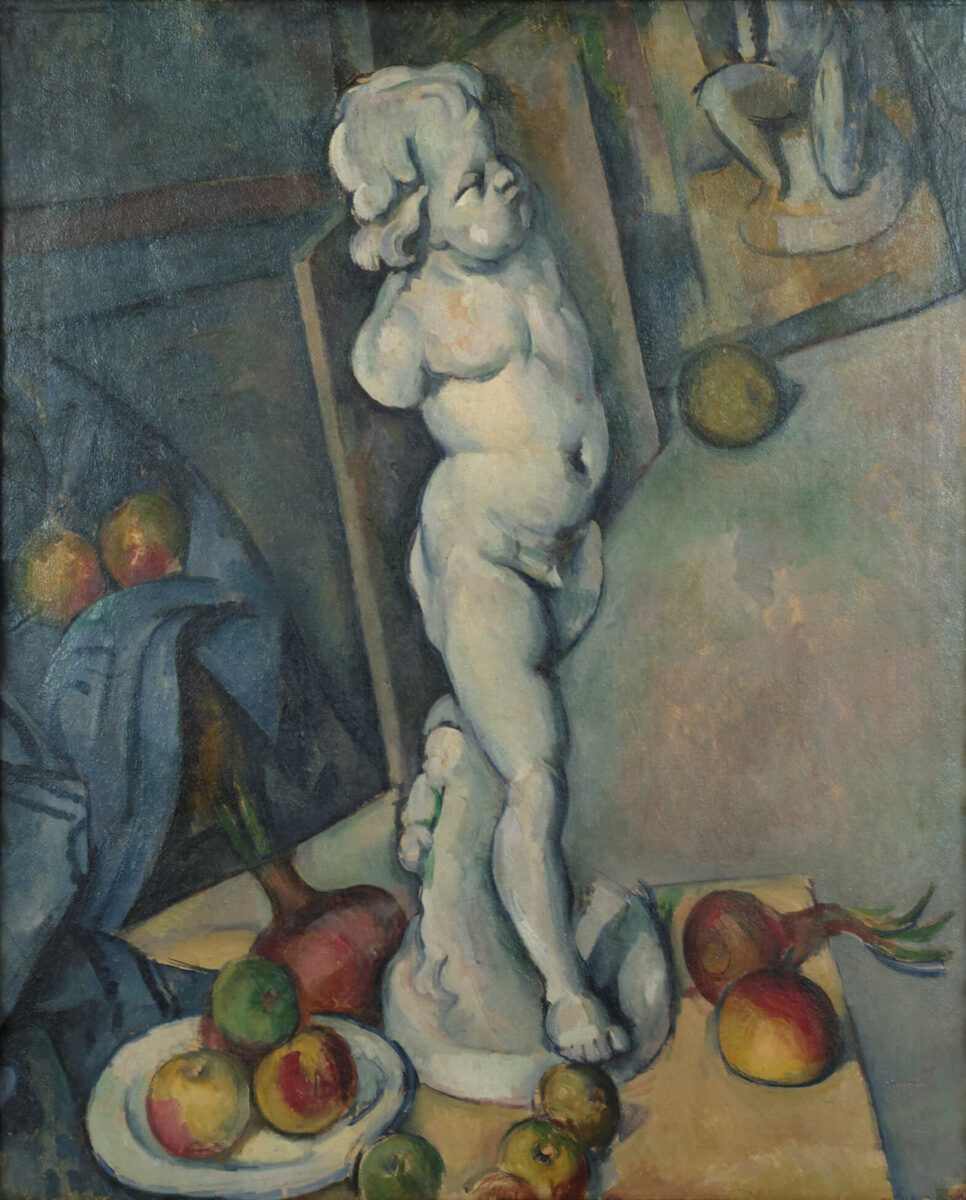

Her early training there included drawing from the displays of taxidermy animals in the natural history museum and art history lessons structured around reproductions of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. Falk recalls that it was an image of a Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) painting featuring a reddish-orange dog that turned her off of these lessons once and for all—the unrealistic palette was too far outside the realm of her teenage desire for pragmatic rendering.

Moving West in Search of Work

Despite her talent, Falk did not envision becoming an artist at this stage of her life. Like her parents, she loved music—especially singing. Around the time that she denounced her extracurricular art lessons, she was recognized for her vocal skill in her church choir performances, and she was active in a local Mennonite girls’ club. She began singing lessons, and an anonymous patron funded her instruction in conducting and theory.

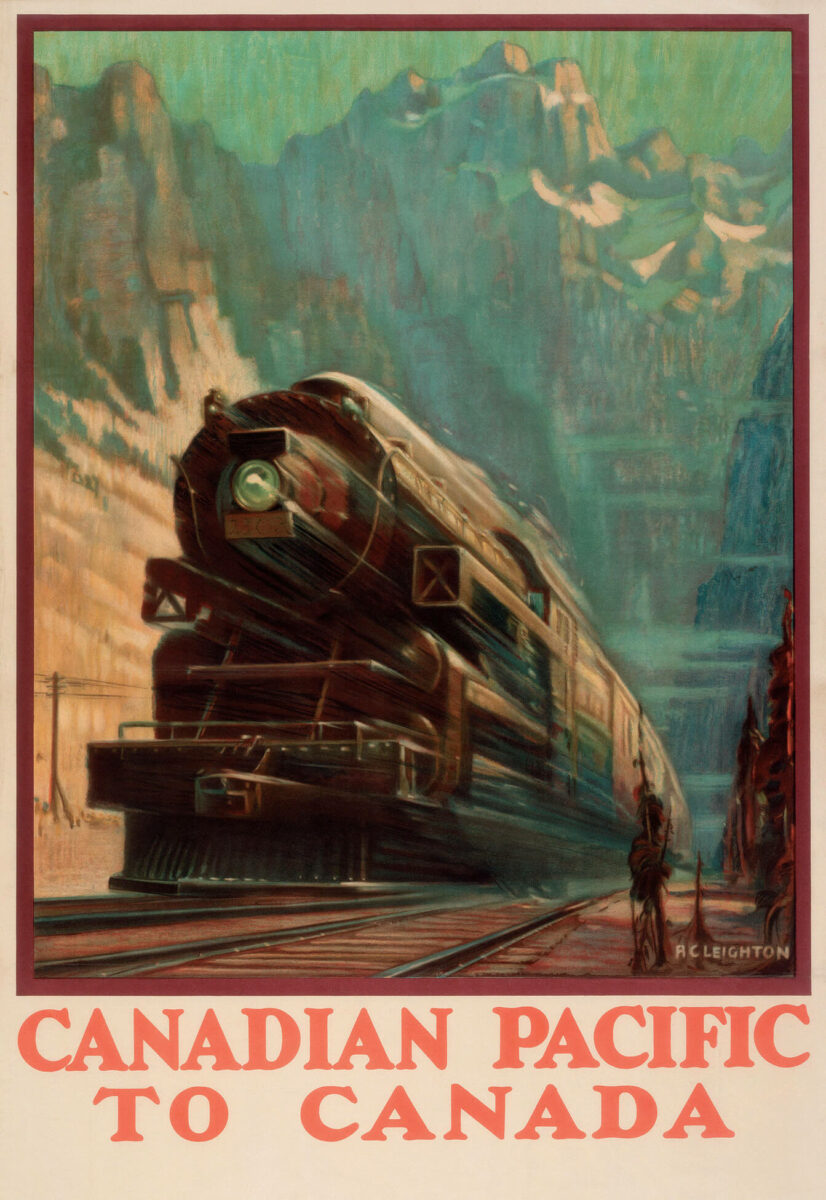

She saw herself pursuing a career in music, but in 1944 her hopes were dashed. At age sixteen, just after Falk had completed grade nine, her family was informed that they had to pay back a debt they owed to Canadian Pacific for their steamship passage from Russia to Canada. Both of her brothers had moved away from home by then, and her mother did not speak English and was of poor health. The responsibility fell to Falk to leave school in order to find full-time work.

After a false start as a nanny in the summer of 1944, Falk found a job at the packing plant of Macdonalds Consolidated, a food wholesaler. She would work there, packaging foodstuffs to be sold at supermarkets, for the rest of her time in Winnipeg. To counter the monotony of long hours on the warehouse floor, Falk led rousing singalongs with her co-workers. While “filling cellophane bags with raisins, dates, brown sugar, peas, beans, and chocolate rosebuds,” the women sang hopeful songs of love and laughter.

It was distressing for Falk to leave school—she was a good student and saw education as her ticket to a more comfortable and fulfilling life. Thankfully, a year after joining the working community, she discovered that she could complete high school by correspondence. In order to balance her studies and her job, she had to give up her music lessons, although she continued to sing in the church choir.

In 1946, when Falk was eighteen, she and her mother, along with her brother Gordon and his wife Edith, all moved to British Columbia, joining her brother Jack and his wife Vera, who had found a home in Vancouver after the Second World War. Falk and her mother were unsettled for the first while, staying in the living room of Mrs. Falk’s cousins in Yarrow, a small Mennonite community, and then renting a room in the house next door. In this rural setting, Falk picked berries and worked in a poultry processing plant to support herself and her mother.

The town of Yarrow is now a semirural suburb of Chilliwack, but when Falk moved there with her mother, it would have borne quite a resemblance to a Mennonite community in Russia. It was essentially a self-sufficient village—all of the businesses and amenities were owned and operated by Mennonites, who continued to speak in the German dialect that formed the foundation of their heritage. In the shadow of a war fought against Germany, the non-Mennonite inhabitants of the region responded to this with fear and suspicion.

The Mennonite community in Yarrow had provided a safe landing for Falk and her mother, but in the spring of 1947, following a short stint when Falk worked as a hotel waitress in Chilliwack, they moved to Vancouver to be closer to family and have access to better job opportunities. Their means were still extremely limited—they lived in two rented rooms at East 25th Avenue and Fraser Street—but Falk was happy to be in the city with its many amenities. Its “bright lights and busy sidewalks” were enchanting to her. She and her mother joined a nearby church, which provided them with friendship, community, and purpose, thus easing their transition to their new setting.

Falk’s first employment in Vancouver was at a luggage factory, where it was her job to sew the pockets inside of suitcases. She had been sewing her own clothing since she was a youngster in Winnipeg, but it was difficult to become skilled on the industrial equipment. “It seemed as if I broke hundreds of needles,” she has said. However, she eventually mastered the machine and even earned herself the nickname “Speed.” As Robin Laurence notes, curators and critics later saw this job “as formative to her capacity for detailed handiwork and repetition within the context of artmaking,” qualities that can be seen in Three Cabbages, 1978.

When the foreman moved on to another luggage factory, he encouraged Falk to follow. She learned some hard lessons about the work world at the second factory—it wasn’t unionized; therefore, raises were not forthcoming and the women were paid less than the men. Nonetheless, Falk stayed in the job, tenaciously completing her high school diploma by correspondence at the same time.

Reluctant Teacher

To her delight, Falk was able to join a church choir and resume her music lessons in Vancouver. Her mother purchased a used violin for her as a gift for her first Vancouver Christmas, and she began lessons with Walter Neufeld (1924–2004), an acclaimed musician and conductor with Mennonite roots very similar to Falk’s. She also studied music theory with Neufeld’s brother Menno, an accomplished choirmaster.

Music was Falk’s first love, and she imagined herself becoming a successful violinist. She did so well in her first year of lessons that she was advanced to grade five. Unfortunately, during the next two years, it became evident that she had perhaps started her training too late, and after poor performances in her grade five and six violin exams, she abandoned her study. She would not be the professional musician she dreamed of becoming.

Both Falk’s mother and violin teacher recognized that she was disheartened about not being more successful with the violin and that she was increasingly despondent about her factory job. They encouraged her to pursue teaching as a career, a prospect she initially described as being “unspeakably dreary.” In need of a change, however, she enrolled in a one-year teaching certificate program at the Provincial Normal School in Vancouver in 1952. Participants learned the how-tos of teaching primary school, and the program also offered refresher instruction in core subjects—including art.

In 1953, Falk took on her first teaching post at a school in Surrey. She was disappointed to find that at a salary of $1,800 a year, she was making less than she had at the luggage factory, and she found it challenging to support herself and her mother on the meagre income. She purchased a house with money borrowed from—and promptly paid back to—a woman from their church, but she sold the house to buy a car and became a renter again. Falk recalls having a good relationship with her principal, who admired the artistic achievements of her students, but she ended up quitting the Surrey post—she feared that the district school inspector would demand her dismissal once he realized that she had not marked any of the work she had assigned to her students. In 1954 she joined the staff of the Douglas Road Elementary School in Burnaby, remaining there until 1965.

Falk attended a summer program that provided additional training for teachers in 1955 and 1956; she took courses in academics as well as in design, drawing, and painting. The art instruction was led by William D. West (1921–2007), a Victoria-based artist and high school teacher whose approach involved a combination of modernist principles and fundamentals of form. Although West’s aesthetic was less emotive than the German Expressionism to which Falk was drawn at this time, his inclination toward depicting natural and built landscapes using reduced, geometric shapes would have provided her with the building blocks for the powerful compositions she sought to create. Falk’s interest in experimenting with form is evident in early works such as The Staircase, 1962.

In 1956 Falk met Elizabeth Klassen, a fellow teacher who came from a background that was remarkably similar to her own. Klassen was also of Mennonite heritage; she had been born in Russia in the same year as Falk, prior to her family’s immigration to Elie, Manitoba, in 1929. Like the Falks, the Klassens experienced hardship in the Prairies and eventually moved to British Columbia in search of a better life. Klassen also laboured in working-class positions before attending Normal School, and she acquired her Bachelor of Education by attending summer school sessions while teaching. They formed an instant bond.

The two women have remained lifelong friends, and Klassen’s support was foundational to Falk’s creative development. Falk once admitted that “the last thing I ever wanted to be was a teacher,” but she would become very accomplished, recognized for her skill in providing instruction in art, literature, and particularly music. While she entered the profession “unwillingly, gritting my teeth,” Falk now acknowledges the payoff from her decade spent teaching. It not only provided her with a steady income but also the opportunity to have an impact on students with whom she would one day reconnect. As she quips in her memoir, “No suitcases have come back to talk to me, and not one Safeway bag filled with beans.”

Apprentice Artist

Ultimately, Falk’s pursuit of teaching was what prompted her return to practising visual art, as in order to get a university degree and upgrade her teaching status, she began taking summer and evening art courses in painting and drawing through the Department of Education at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in 1957.

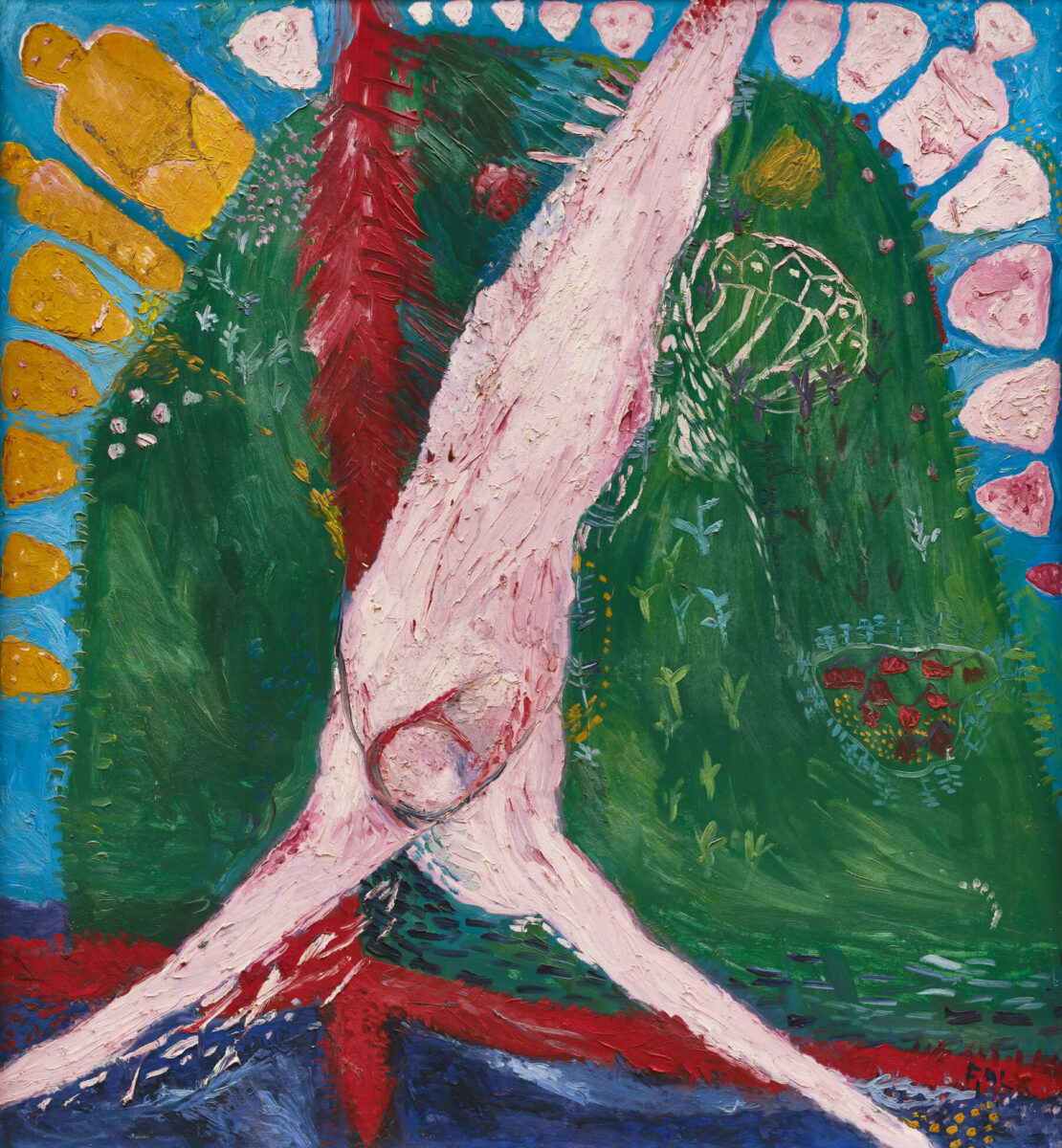

As a painter, she found herself drawn to the distorted visions of reality produced by the German Expressionists—despite non-figurative American Abstract Expressionism being more popular at the time—and sought to always “create a concrete image that was recognizable.” She had no interest in “pretty pictures” and instead intended to “paint strong works.”

The first public presentations of Falk’s artwork would take place shortly after her enrolment at UBC—she contributed paintings to the B.C. Annual Exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1960 and the Northwest Annual Exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum in 1961. The following year she attended the Seattle World’s Fair, where she would have seen the work of the American Abstract Expressionists, including Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Mark Tobey (1890–1976), and European modernists such as Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and Franz Marc (1880–1916).

In 1964 there was a further opportunity to see iconic works of art by European artists, including modernists Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), and Renaissance artists Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), in the exhibition The Nude in Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery. In 1965, Falk went to Europe for the first time. Many of Falk’s works from the early to mid-1960s, such as St. Ives, 1965, and Crucifixion I, 1966, bear the mark of her art historical and geographic travels.

Hard-edge painting, Op art, and Pop art were in vogue at the time, but Falk bucked the trends followed by her peers to pursue Expressionism instead. “I’d done enough factory work in my life,” she has said of her distaste for the aforementioned movements. “I wasn’t interested in mimicking a machine.”

At this time, Falk was still working on her degree at UBC. She had moved from the Bachelor of Education program to a fine arts in education degree. Her confidence as an artist was steadily growing as she learned how to create balance in a composition and make “a broad and meaningful brushstroke.” She had been taking studio and art history classes, studying with Lawren P. Harris (1910–1994), James Alexander Stirling MacDonald (1921–2013), Jacques de Tonnancour (1917–2005), Audrey Capal Doray (b.1931), David Mayrs (1935–2020), and Ron Stonier (1933–2001), but upon changing programs, she began studying ceramics with Glenn Lewis (b.1935).

Lewis had apprenticed with the renowned British studio potter Bernard Leach (1887–1979) in Cornwall, England, and while he did teach his students to produce functional ceramics, he also taught ceramic sculpture. Falk has acknowledged the importance of Lewis’s emphasis on being open “to an awareness of the forms and rituals of everyday life” on her career. Under his tutelage, she has said that she and her fellow students were turned into “more thinking people” who learned how to pay attention to the “art of daily living.” It was while studying with Lewis that Falk made her first individual ceramic shapes: “a leg, shoes, boots, a suit coat.” Ordinary objects such as these would later become one of her artistic signatures, appearing in works like Eight Red Boots, 1973, Soft Couch with Suit, 1986, and Standard Shoes, The Column, 1998–99.

A Turn to Ceramics and Performance

In 1965, Falk made a withdrawal from her pension fund and took a leave from teaching in order to focus on making art. A few years earlier, in 1962, she had bought her second house: a wartime bungalow on East 51st Avenue near Fraser Street, with a down payment borrowed from her friend Elizabeth Klassen and a second mortgage arranged through the B.C. Teachers’ Federation. Owning the house enabled her to manage financially through this transition, as she could rent out her spare room, or even the whole main floor, for extra income. Through economical living, Falk never had to go back to teaching elementary school, although she would later teach visual art part-time at UBC in 1970–71, and again from 1975 to 1977.

She began to make the paintings that would become the content of her first solo exhibition in 1965 at the Canvas Shack in Vancouver. In his review of the exhibition, David Watmough affiliated Falk’s paintings with German Expressionism, the movement that she herself acknowledged as an important touchstone—the distorted colour, scale, space, and forms of the style influenced works such as The Banquet, 1963, and The Waitress, 1965. In a statement that now seems incongruous with Falk’s practice, the critic noted, “Whenever the human figure occupies a central place in Miss Falk’s compositions, her canvases seem to spring to life—in a manner that her still lifes and domestic scenes rarely do, in spite of the vitality and raw energy of her palette.”

In the summer of 1965, Falk started a ceramics studio with a classmate, Charmian Johnson (1939–2020). In 1967, Falk received a short-term grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, and she and Johnson built a 4.5-square-metre gas kiln in Falk’s garage. That year, Falk also became a member of the Intermedia art collective and a part of the stable of artists at Douglas Gallery (later renamed Ace Gallery) in Vancouver.

At this point she had become fully invested in sculpture, saying, “My ideas for paintings became sculptures instead.” Her first major professional success came with the 1968 show Living Room, Environmental Sculpture and Prints, in which she exhibited Home Environment, filling the Douglas Gallery with an installation created from screenprinted wallpaper and framed prints on the walls, as well as sculptures of household items—some, such as a pink armchair, made from repurposed thrift-store finds, and others, such as a package of ground beef, fashioned from clay. Between 1967 and 1970, she worked on three ceramic sculpture series: Fruit Piles, 1967–70; Art School Teaching Aids, 1967–70 (among them Art School Teaching Aids: Hard-Edge Still Life, 1970); and Synopsis A–F, 1968; as well as the Shirt Drawings series, 1968–70.

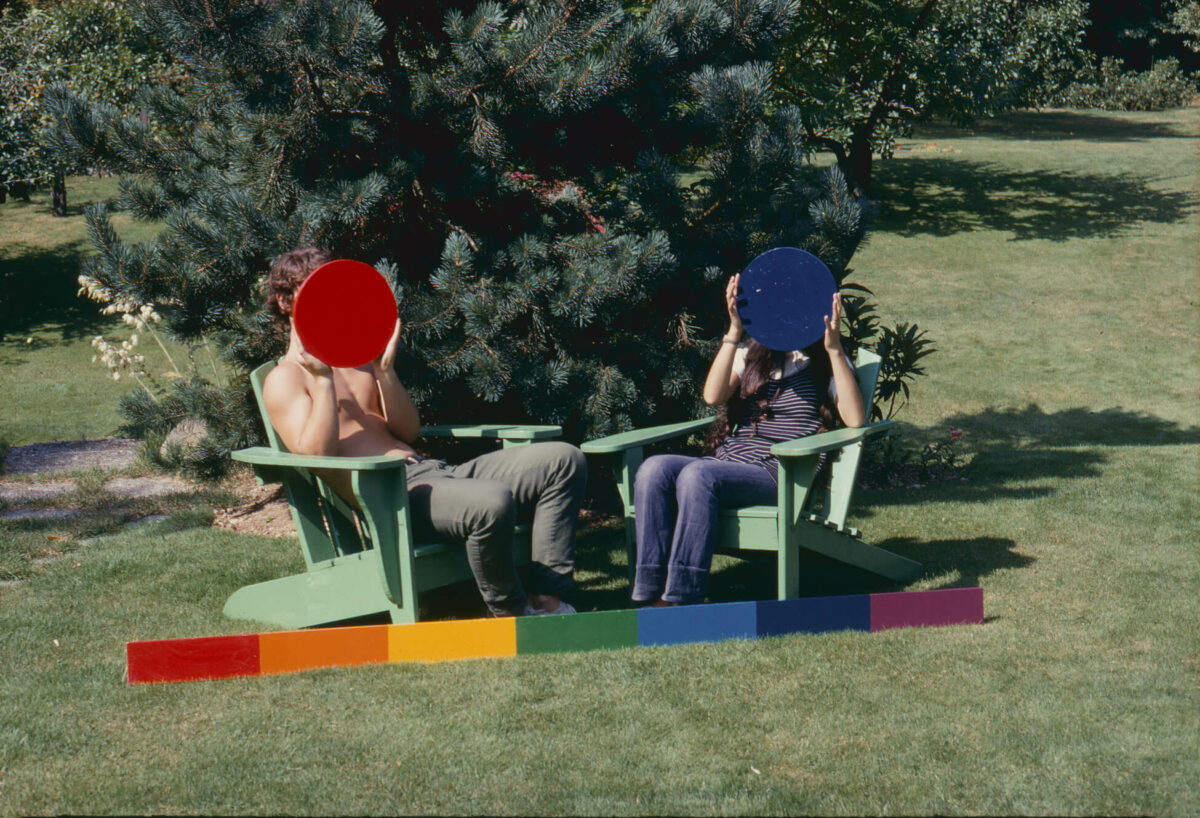

In 1968, her dealer, Douglas Chrismas, enrolled Falk in a workshop led by Deborah Hay (b.1941), a member of the Judson Dance Theater, an experimental collective of dancers, composers, and visual artists who performed at the Judson Memorial Church in New York. Hay’s workshop was co-hosted by the Douglas Gallery, Intermedia, UBC, and the Vancouver Art Gallery. Falk discovered that she had an affinity with performance art—it provided her with a means to explore the images and themes that interested her, with the added elements of movement, sound, and time. “The performance process felt very natural,” Falk has said. “It was like music.” She produced her first works of performance art, including A Bird Is Known by His Feathers Alone, later in 1968.

A Bird Is Known by His Feathers Alone was a complex work with a variety of props and costumes and a serpentine choreography of actions: Falk washing her face and applying Rogers Golden Syrup to it; artist Tom Graff (active from the 1970s), Falk’s friend and sometimes performance partner, creating a large drawing with cold cream, lipstick, and powder; and other performers using their prone bodies to push plastic cocktail glasses filled with cherries and ceramic oranges across the stage.

This piece was first presented as part of Chromatic Steps, an Intermedia exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery in October 1968. In 1969, New York–based performance artists Yvonne Rainer (b.1934) and Steve Paxton (b.1939), both of whom were also affiliated with the Judson Dance Theater, came to the Vancouver Art Gallery and Intermedia; Falk took part in their performances and workshops as well.

Falk would create some fifteen performance artworks—or Theatre Art Works as she called them—between 1968 and 1972, including Girl Walking Around Square Room in a Gallery, 1969, notable for its innovative combination of performance and projected film, as well as the better-known Some Are Egger Than I, 1969, and Red Angel, 1972. She continued performing her artworks until 1977.

The use of projection in Girl Walking Around Square Room in a Gallery seems unique in Falk’s practice. However, Falk revised Some Are Egger Than I after its first performance so that it included a slideshow backdrop depicting her being pelted with eggs in Eighty Eggs, 1969, a Douglas Chrismas theatre piece. In her performances, as in her ceramic works, Falk “liked to use ordinary, everyday activities; eating an egg, reading a book, drinking tea, washing [her] face, putting on makeup, cutting hair.” The sense of ritual in her daily life carried over into what she expressed in her work.

In his introduction to the book Performance au/in Canada 1970–1990 (1991), author Clive Robertson traces the origins of Canadian performance art to the Hay, Paxton, and Rainer workshops in Vancouver. He also acknowledges that of the people who participated in them—in addition to Falk, well-known Canadian artists Glenn Lewis, Jorge Zontal (1944–1994), Helen Goodwin (1927–1985), and Michael Morris (b.1942) also took part in the workshops—it was Falk and Zontal whose subsequent performance work showed the greatest affinity to the form practised by their instructors.

Falk’s presentation of Theatre Art Works at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1972 drew the attention of art critic Joan Lowndes. Writing on A Bird Is Known by His Feathers Alone, Lowndes noted that “the scattering of oranges, glasses and squashed cherries as they finish is a study in process and randomness.” In hindsight, Falk thinks that her audience “didn’t know what to make of them.” Robertson, however, argues that “Falk’s complex works are to Canadian performance art what Lisa Steele’s [b.1947] and Colin Campbell’s [1942–2001] early work was for video: dauntingly sophisticated and confident, work that other artists, knowingly or not, would re-cycle.”

Menswear and Marriage

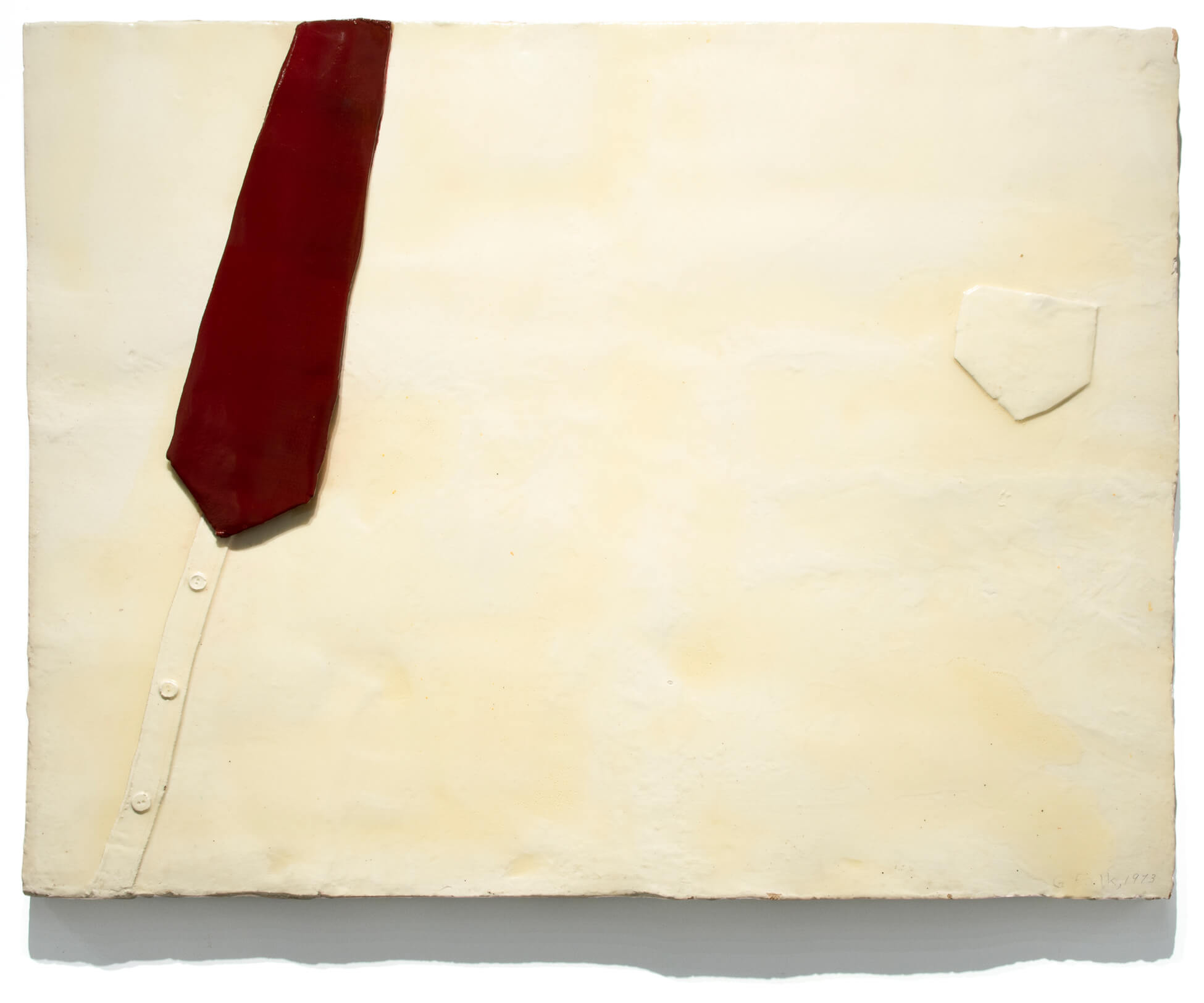

Falk continued to work in ceramic sculpture and drawing in a number of series that take menswear as their primary subject: the ceramic Synopsis A–F, 1968; Shirt Drawings, 1968–70; and the ceramic and found object Man Compositions, 1969–70. She has said that during this period she was “focused on the symbolic possibilities of men’s clothes, the presence and power they represented.” She participated in exhibitions such as the 5th Burnaby Print Show, 1969, and Works Mostly on Paper, 1970, at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

She exhibited widely across Canada and in the U.S. In 1971 she was commissioned to produce two large-scale ceramic murals for the cafeteria of the Department of External Affairs building in Ottawa; in response to this invitation, and with a nod to the menswear-focused work she had just completed, she would install Veneration of the White Collar Worker #1 and Veneration of the White Collar Worker #2, 1971–73, two wall-sized works comprising twenty-four ceramic panels representing variations on men’s shirt fronts with ties.

Prior to the completion of this major work, Falk’s mother, who had been living at Valleyview, a residence for geriatric psychiatric patients in Coquitlam, died of a heart attack in 1972. Falk’s relationship with her mother had been complex, and she had been largely responsible for her mother’s care since she was teenager when her older brothers left home.

After her mother’s death, Falk stopped creating new performance artworks (although she would continue performing the works conceived between 1968 and 1972 until 1977). With more time and freedom, she was able to devote herself more fully to producing in the studio, and in 1972–73 she created one of her best-known ceramic sculpture series, Single Right Men’s Shoes, which she would go on to exhibit, for the first time, at the Canadian Cultural Centre in 1974 during a month spent in Paris.

It was during this busy time in 1973 that Falk entered into a relationship with prison inmate Dwight Swanson. He had heard Falk being interviewed on the radio and had written her a letter. Falk had done work in prisons through a Vancouver Art Gallery program that connected artists with incarcerated individuals and had performed in them with her church choir, so it was perhaps not surprising that Swanson’s letter led to Falk corresponding with and eventually visiting him in prison.

While Falk recounts that her friends were anxious about her burgeoning relationship and her ultimate marriage in November 1974 to a career criminal (who was twenty years her junior), she rationalized the decision by stating, quite simply, that she loved him. However, she also admits that “agreeing to marry him was probably not a rational decision, but once I’d made it, I stuck to it stubbornly.” Swanson’s behaviour during their short-lived marriage was erratic, and he would soon relapse into his criminal behaviour. Falk and Swanson separated after just eight months and formally divorced in 1979.

Throughout the 1970s, Falk continued her exploration of ceramic form in a number of series that provided her with the platform to manifest the fantastic imagery that she saw in her mind’s eye. The series were all essentially variations on the still life, an artistic genre that had been central to her practice since her earliest days as an artist.

While works like Fruit Piles, 1967–70, and Single Right Men’s Shoes possess elements of the still life, as compositions built from numerous iterations of the same object, they become singular despite their multiplicity. It is in series like Art School Teaching Aids, 1967–70; Table Settings, 1971–74; Picnics, 1976–77; and even Saddles, 1974–75—ceramic sculptures that relinquished iconic structure for a more complex, varied composition—that we see Falk’s hearkening back to the Still Life paintings, 1962, which she considers her earliest work produced outside of the influence of a teacher.

The Picnics series was premised in an interest that had first appeared in a 1971 Theatre Art Work also entitled Picnic. Falk has said that she “sometimes think[s] of [Picnics] as nice head stones” and that “they express a lot of the emotion related to the time of [her] husband’s trials and imprisonment.” He had owned a black 1936 Ford business coupe with yellow and red flames painted on its doors. The vehicle became a key element in the trials that saw Swanson imprisoned again, and according to Falk, its decorative flames recurred as a motif in the Picnics series, as can be seen in Picnic with Birthday Cake and Blue Sky, 1976. The ceramic Picnics, which also include Picnic with Clock and Bird, 1976, Picnic with Red Watermelon #2, c.1976, and Picnic with Fish and Ribbon, 1977, garnered much praise from curator Ann Rosenberg, who called them “a perfect marriage of technical competence and visual force.”

In the opening lines of her introduction to the catalogue for Gathie Falk Retrospective mounted at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1985, director Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker writes, “Many critics have viewed Falk’s work as engaged in exclusively female if not feminist art. Falk rejects such interpretations pointing out, for example, that the still life is, ‘the fodder of almost every [major] artist.’” Of course, the inclination toward the still life as subject has come with the tendency for interpreters of Falk’s work to associate it with either the metaphors of bounty and life or those of decay and death associated with the genre.

There is certainly an element of a philosophy for living in Falk’s inclination to represent the things around her, for as she has noted, “I feel that unless you know your own sidewalk intimately, you’re never going to be able to look at the pyramids and find out what they’re about. You’re never going to be able to see things in detail unless you can look at your kitchen table, see it and find significance in it—or the shadow that is cast by a cup, or your toothbrush. Seeing the details around you makes you able to see large things better.” Falk’s commitment to seeing the details around her own home can be seen in many projects from the late 1970s and early 1980s, including Border in Four Parts, 1977–78, and the Cement series, 1982–83.

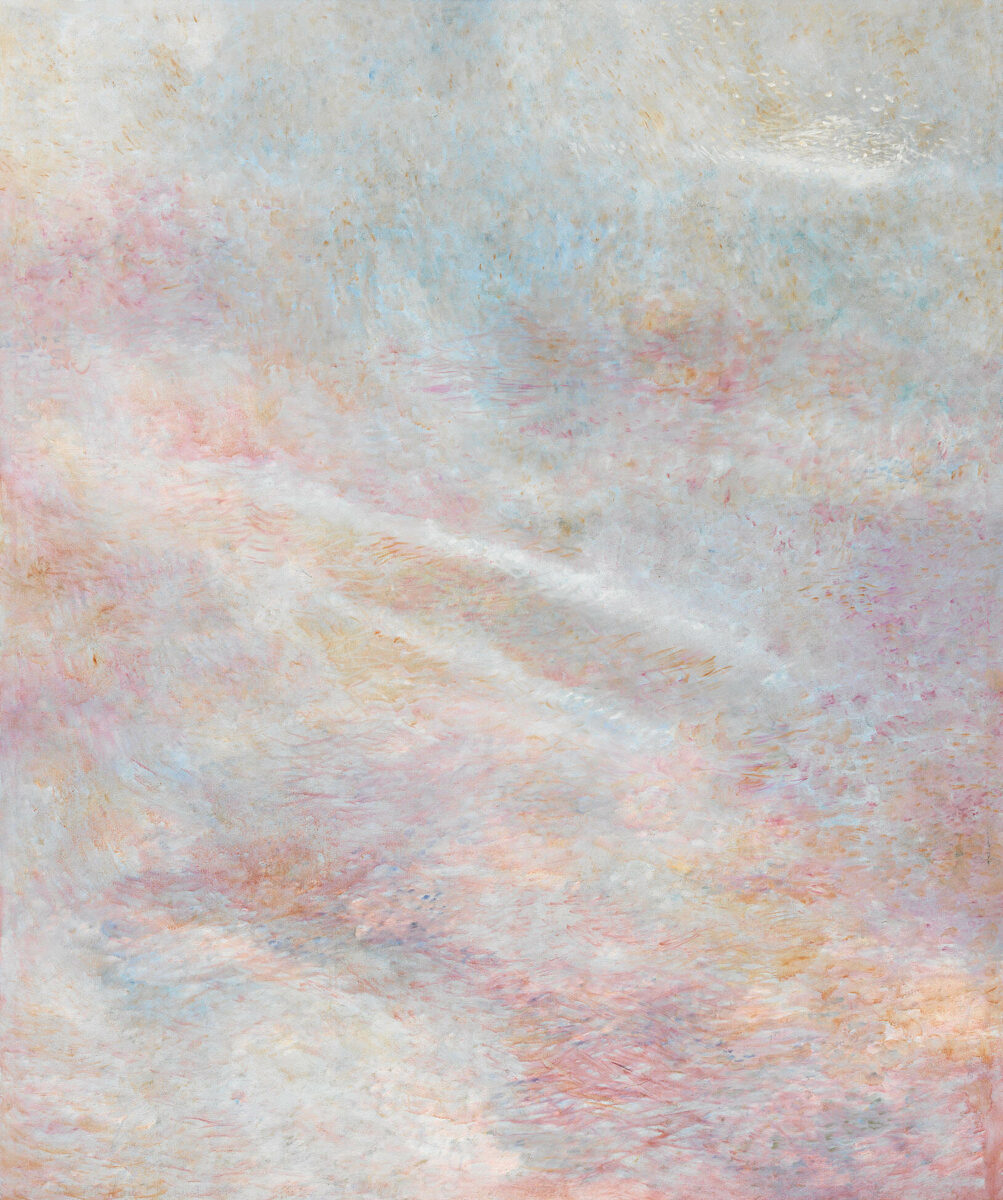

Success and a New Millennium

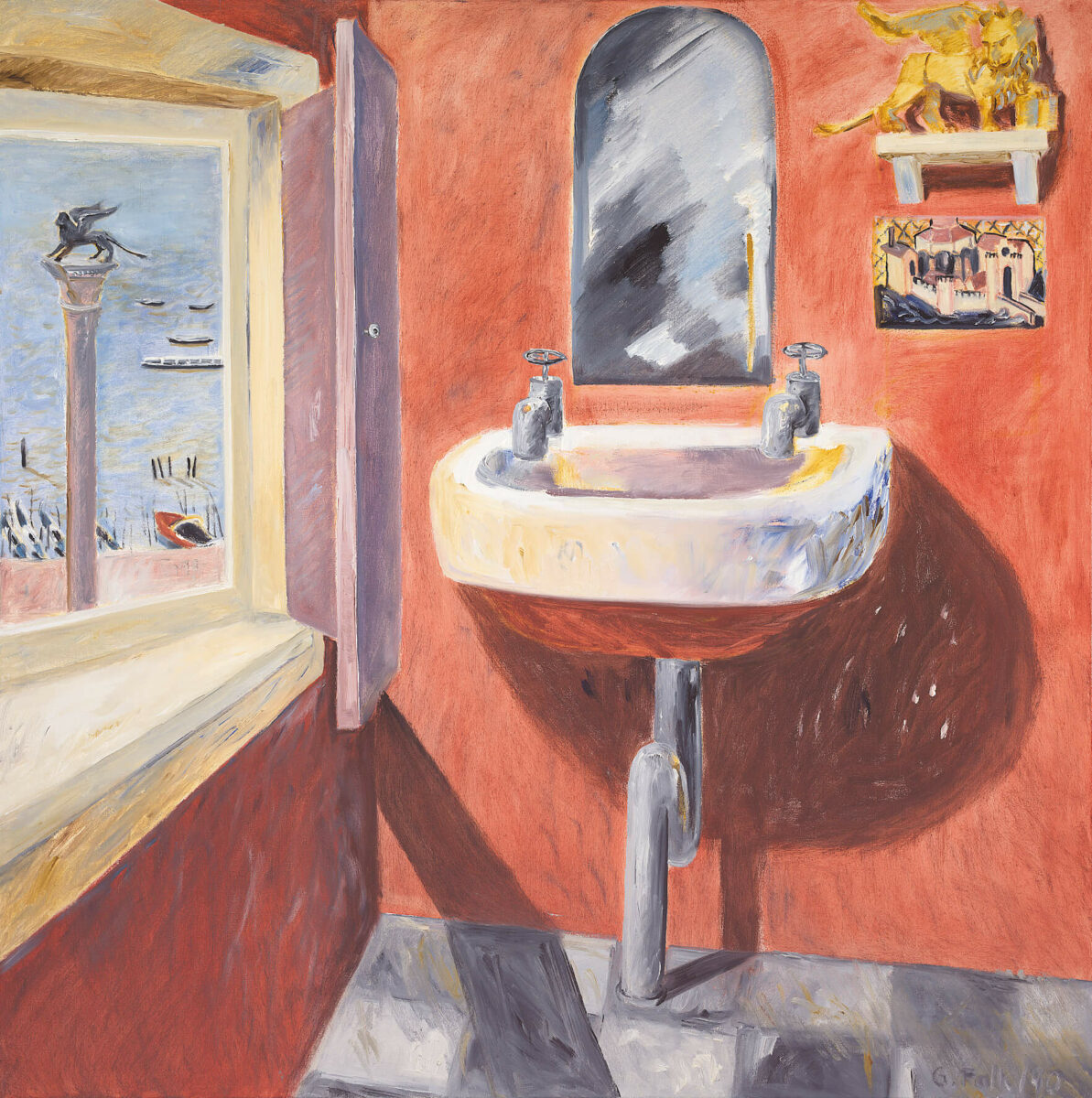

Late in 1977, after a hiatus of eleven years, Falk began to focus on painting once again. She was inspired after seeing frescoes by Giotto (1266/67–1337) during a month-long trip to Venice. Her first series after the return—the Border paintings, 1977–78—were depictions of the edges of the gardens at her own and her neighbours’ homes. This approach of taking an intimate view of some subsection of a landscape, without providing any points of reference or context, would become a recurring strategy in Falk’s next series, Night Skies, 1979–80, and Pieces of Water, 1981–82. In her memoir, Apples, etc., Falk describes the conceptual premise at the core of the latter project: “I had the idea that each painting would depict a big chunk of water, which I had cut out of the sea with a long, sharp knife. The compositions are tilted up, so that shimmering colour fills the canvas, with no visible shore or horizon line.”

With painting now the medium of choice, in 1978, when Falk received a commission from the B.C. Central Credit Union to create a mural for the foyer of their administration building, she produced Beautiful British Columbia Multiple Purpose Thermal Blanket, 1979, a gigantic painted quilt (although Falk prefers the description “sculpted painting”). Falk would go on to create two more important public art projects: Diary, 1987, commissioned by architect Arthur Erickson for the Canadian Embassy in Washington D.C.; and Salute to the Lions of Vancouver, 1990, for Canada Place in Vancouver.

Curatorial, critical, and market interest in Falk’s work can be traced back to 1967, when she began to show with the Douglas Gallery. There has been obvious excitement for each new inventive phase of her development since that point, but it was in the early 1980s that serious attention took hold of her practice. In 1982 she exhibited the Pieces of Water series at Equinox Gallery, Vancouver, and Isaacs Gallery, Toronto. She had been showing with Equinox Gallery since 1981 and is still part of its stable. Av Isaacs had approached Falk about representing her when she exhibited Fruit Piles in Vancouver back in 1970, but at the time she said no; it was finally in the early 1980s that the relationship between the two was formalized.

Also in 1982, the Capilano Review produced a double-issue special edition dedicated to Falk’s work; the following year she began working with curator Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker on the Vancouver Art Gallery retrospective exhibition that would open two years later. In 1985, Falk was included in British Columbia Women Artists, 1885–1985, curated by Nicholas Tuele at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, the same institution that would, in 1985, produce and tour an exhibition of her new paintings created between 1978 to 1984.

Painting dominated Falk’s production throughout the 1980s and 1990s, with new major series emerging every year or two and some series containing as many as twenty or thirty canvases: Borders; Night Skies; Pieces of Water; Cement, 1982–83; Theatre in B/W and Colour, 1983–84; Chairs, 1985; Soft Chairs, 1986; Support Systems, 1987–88; Hedge and Clouds, 1989–90; Venice Sinks with Postcards from Marco Polo, 1990; Development of the Plot, 1991–92; Clean Cuts, 1992–93; Constellations, 1993; Nice Tables, 1993–95; Heads, 1994–95; and Apples, 1994–96. Around 1997–98, she returned to working in sculpture and installation, later commenting “After I had devoted some eighteen years straight to painting, a new idea dropped into my head. What I saw, fully formed, was a sculpture of a woman’s dress…”. The papier mâché Dresses, 1997–98, became a new series, as did Standard Shoes, 1998–99.

In order to accommodate this remarkable wave of production throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Falk had constructed a purpose-built structure behind her home—a 1920s Craftsman house in Kitsilano that she had moved to in 1970—in 1983. A few years later, Falk decided to build a new house that she would design to meet her specific needs, which would include spaces to create and store work and “the social part of the main floor” consisting “of a great room.” She purchased property in East Vancouver and moved to her custom-built residence in 1989, at long last finding a sense of rootedness. She lives there to this day, surrounded by her art, her garden, and her friends.

In 1999, the Musée régional de Rimouski in Quebec mounted Gathie Falk: Souvenirs du quotidien and the Vancouver Art Gallery invited Falk to develop a major retrospective exhibition to open in February 2000. In her memoir, Apples, etc., Falk noted that she wasn’t expecting a lot of attention in the new millennium—she had, after all, turned seventy-two in January 2000. However, the work, opportunities, and acknowledgements kept coming.

In fall 2000, Equinox Gallery in Vancouver supported the production of an important series of cast bronze sculptures at the foundry of well-known Canadian sculptor Joe Fafard (1942–2019). Inspired by the light and landscape of the foundry’s Prairie setting, Falk called the series Agnes, after the Saskatchewan-born abstract painter Agnes Martin (1912–2004); Agnes (Black Patina), 2000–2001, illustrates a connection between this body of work and the Dresses series, 1997–98. Falk continued her sculptural expression with series and installations such as Portraits, 2001; Shirting, 2002; and Dreaming of Flying, Canoe, 2007, executed in papier mâché, a medium she had learned to use while teaching.

Falk had received the Order of Canada in 1997; in the 2000s, the awards continued with the Order of British Columbia in 2002; the Governor General’s Award in Visual Arts in 2003; and the Audain Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts in 2013. Upon receipt of the Audain Prize—at which point Falk was eighty-five years old—she told her audience that she hoped the prize did not mark her career’s end.

Living Legacy

Falk continues to be active in the studio, producing new paintings and regularly mounting shows of new and old works at Equinox Gallery, Vancouver, where she has been showing since 1982, and Michael Gibson Gallery, London, Ontario, at which she started showing in 2013.

In 2015, Falk mounted The Things in My Head at Equinox Gallery; it was the largest exhibition of her art since the Vancouver Art Gallery’s retrospective, Gathie Falk, in 2000. While it was presented in the setting of a commercial gallery, The Things in My Head approached the structure of a retrospective, bringing together seventy works spanning the course of Falk’s six-decade career from private and public collections.

In 2018, with the support of Robin Laurence, a long-time advocate of Falk’s work and an independent writer, critic, and curator based in Vancouver, Falk released Apples, etc.: An Artist’s Memoir. This publication is an anecdotal unfolding of stories in Falk’s charming yet matter-of-fact voice; she deftly weaves together tales of her life before and after her entry into Vancouver’s art scene. In 2022, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection created a career-spanning survey of Falk’s work entitled Gathie Falk: Revelations.

Throughout her career, Falk has pushed against the tendency of curators and critics to invoke her Mennonite upbringing and beliefs and her generally compelling biography as foundational to her imagery. While Apples, etc. marries the artist’s recounting of her personal experiences with anecdotes about the conception and production of some of her key works, Falk always follows her own counsel and does not make any specific links between the real-life experiences she shares and the images that she returns to again and again. However, the adjacency of her autobiography to the personal descriptions of her work creates the opportunity for readers to sense how life inevitably informs the work poetically, if not causatively. In Gareth Sirotnik’s 1978 article for Vanguard, “Gathie Falk: Things That Go Bump in the Day,” Falk recognized an affinity between her religion and the simplicity and control of her work, noting that “if you have a strong religion, you’re disciplined for life.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements