Carr travelled extensively, learning from European, American, and indigenous forms and receiving formal training at art academies as well as with private tutors. She continued to grow in artistic power throughout her life as a result of her own intense observation and vigorous experimentation in a variety of methods and media, reflecting the fusion of her wide-ranging influences.

Early Work, 1890–1910

Carr began her study of art in San Francisco at the California School of Design in 1890. The school later became known as the training ground for several West Coast American Impressionist painters, but its teachings were conservative: students progressed from drawing plaster casts of classical art to still lifes to nude models—though true to her Victorian upbringing, Carr refused to attend classes in the latter. (When she studied in England in 1899–1904, she overcame her qualms, writing in her autobiography years later, “I had dreaded this moment and busied myself preparing my material, then I looked up. Her live beauty swallowed every bit of my shyness.”

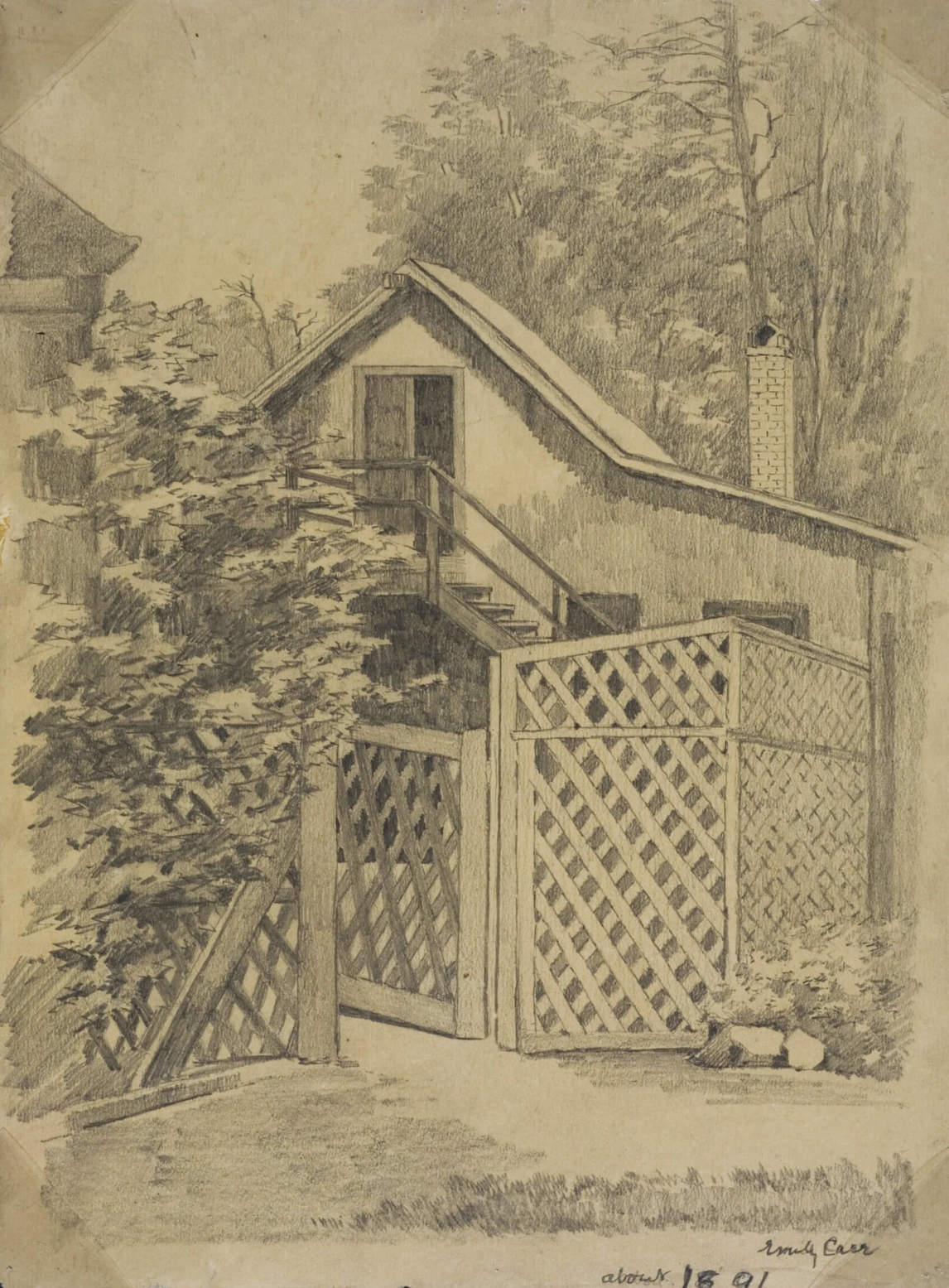

Carr described her work in California as “hum drum and unemotional—objects honestly portrayed, nothing more.” After three years she returned to Victoria and taught children’s art classes in her first studio, the loft of a converted cow barn in the yard of the family home, a scene she depicted in Emily’s Old Barn Studio, c. 1891. In the late 1890s Carr travelled to the Nuu-chah-nulth village at Ucluelet on the west coast of Vancouver Island and documented it through a series of drawings.

When she had saved enough money from her studio classes, Carr embarked in 1899 on her second study sojourn, in London. She had heard of the British art schools from two of her friends in Victoria, the artists Sophie Pemberton (1869–1959) and Theresa Wylde, who had studied in England while Carr was in California. Although the stronger art schools of the day were on the Continent, language was a barrier; in London there were also family friends. But Carr arrived at the Westminster School of Art a few years too late. Once a training ground for distinguished artists such as Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) and Dame Ethel Walker (1861–1951), the school had seen its reputation decline after their most distinguished professor, Frederick Brown, left for the Slade School of Fine Art. At Westminster she was taught traditional nineteenth-century design, anatomy, life drawing, and clay modelling techniques, including working from the school’s vast collection of classical casts. Her art from her days at Westminster, such as Chrysanthemums, c. 1900, was unremarkable. Disappointed, she left the school and travelled to Europe.

On May 7, 1901, Carr wrote from England to a family friend, Mary Cridge, about her visit to the Louvre, where she was delighted “to see the very pictures you had heard of & dreamt of half your life. I wondered if I would wake up and find it was a dream.” The scholar Kathryn Bridge speculates that if Carr was in Paris before the end of March, she likely would have seen Exposition d’oeuvres de Vincent van Gogh, the first retrospective of the artist, presented at the Galerie Bernheim Jeune from March 15 to 31. In the autobiography she wrote at the end of her life, Carr recalls that she had begun to think that “Paris and Rome were probably greater centres for Art than London. The art trend in London was mainly very conservative. I sort of wished I had chosen to study in Paris rather than in London.”

Later that year she registered at the Porthmeor Studios in St. Ives, Cornwall, under the tutelage of Julius Olsson (1864–1942) and his assistant, Algernon Talmage; she chronicled his teachings in her illustrated narrative The Olsson Student, c. 1901–2. The school was known for its plein air technique. Olsson insisted that his students set up their easels on the sand, but Carr found that the bright Cornish beaches triggered her migraines. When Olsson left on holiday, Talmage allowed her to go up to the Tregenna Woods to paint. Carr recalled Talmage’s formative advice to “remember, there is sunshine too in the shadows,” as well as his recommending that she see the “indescribable depths and the glories of the greenery, the … crowded foliage that still had breath space between every leaf.”

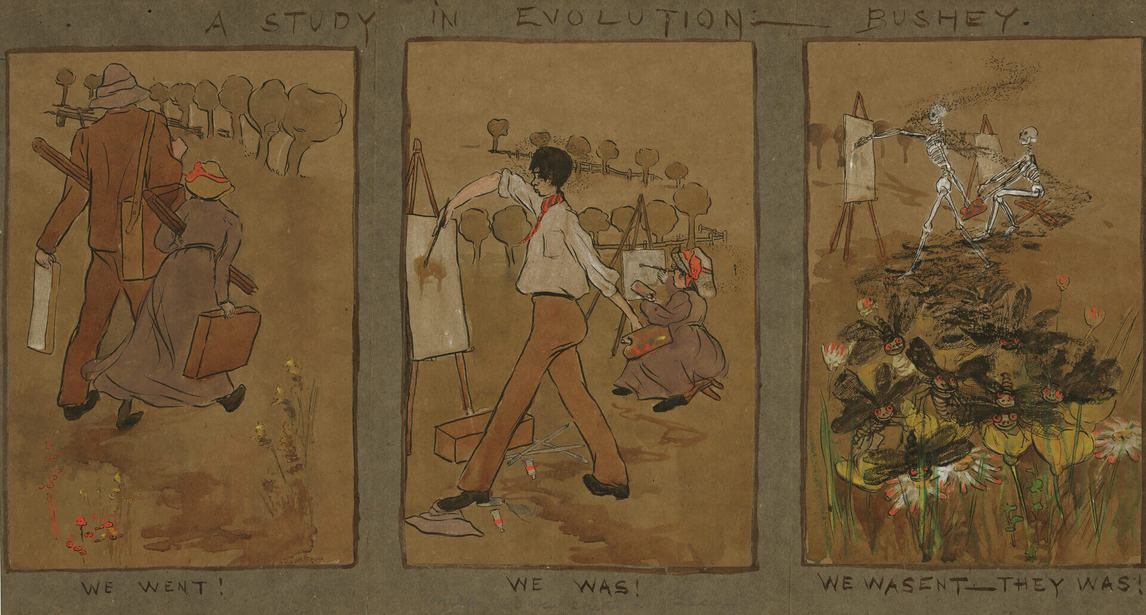

Carr received a withering critique from Olsson on his return. She left St. Ives after only eight months and went to the artist colony at Bushey, Hertfordshire. Before long she rejected the academic teachings of its founder, Hubert von Herkomer (1849–1914), preferring instead to join the more bohemian Meadows Studios in the same small town. There John Whiteley became her tutor, and Carr continued her plein air painting with his encouragement. Whiteley advised her to “see the coming and going among the trees.” When she returned to Canada she began to produce paintings of the towering trees of Stanley Park, a forest reserve in Vancouver.

While Carr was in Alaska in 1907 she painted Totem Walk at Sitka, depicting Tlingit and Haida poles that had been resituated for the tourists. There she met an American artist, likely Theodore J. Richardson (1855–1914), who had also made Sitka a subject of his art. Richardson did extensive research into First Nations culture in Alaska, travelling with indigenous guides and producing plein air watercolours. Some of these were later developed into more extended studio works, though Richardson is best known for his pastels and watercolours of southeast Alaska that document Tlingit art and architecture in the region.

Intrigued by Richardson’s interest in what he described as a mission to preserve a dying culture—a colonial vision that Carr herself shared—she decided to create a series of works that would document First Nations culture and way of life. During successive summers she travelled to northern villages for this purpose; she writes of this time, “Indian Art broadened my seeing, loosened the formal tightness I had learned in England’s schools. Its bigness and stark reality baffled my white man’s understanding. I was as Canadian-born as the Indian but behind me were Old World heredity and ancestry as well…. The new West called me, but my Old World Heredity, the flavour of my upbringing, pulled me back. I had been schooled to see outsides only, not [to] struggle to pierce.”

French Influence, 1910–11

It was not until 1910 that Carr again travelled for study, this time to Paris. “I did not care a hoot about Paris history,” she writes. “I wanted now to find out what this ‘new Art’ was about. I heard it ridiculed, praised, liked, hated. Something in it stirred me but I could not at first make head nor tail of what it was all about. I saw at once that it made recent conservative painting look flavourless, little, unconvincing.” It proved to be the most influential of all her study excursions. She stayed for fifteen months, and here the technical and stylistic training she experienced would change her work irrevocably.

Carr initially enrolled at the Académie Colarossi on the advice of the English artist Harry Phelan Gibb (1870–1948) but left for private study with the Scottish artist John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961). Tiring of the large city she retreated to a spa in Sweden for several months, returning to study outside Paris and then in Brittany under the tutelage of Gibb and, later, the New Zealand artist Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947).

During this time, Carr produced many small paintings, both onsite and in her studio, including such works as Le paysage (Brittany Landscape), 1911, which depicts the French countryside. Gibb, a friend of Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and the expatriate American writer Gertrude Stein, was an important influence, encouraging her to pursue her First Nations project. As she experimented with composition, colour, and execution and came into more intensive contact with contemporary European art movements—primarily Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism, and Cubism—she transformed and developed as a painter. She also admired Gibb’s work: “There was rich delicious juiciness in his colour, interplay between warm and cool tones,” she writes. “He intensified vividness by the use of complementary colour.”

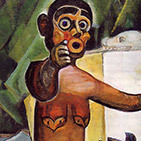

Significantly for her later work, Carr rejected Gibb’s deliberate distortions of the figure and, by extension, the primitivism of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963). In her words, the distortion of the figure was to be done “with meaning, for emphasis and with great sincerity,” as in the Aboriginal sculpture and painting she had seen in British Columbia, and not for formal impact alone.

By the end of her studies in France, Carr had successfully integrated her need to work in a non-urban setting with her desire for creative achievement as an artist. In paintings from this period, such as Autumn in France, 1911, she had, moreover, firmly established the technical approach and stylistic language that were to distinguish her modernity. Her art began to adapt, through simplification of detail and a variety of brush marks. She worked as much in oil as in watercolour, and she experimented with pattern and tonal variation, using high and low tones to create a structure for the painting. Compositions become more strategic, overlaying colour to reveal the patterns in the geography or to create interior scenes—as in French Knitter (La Bretonne), 1911.

The paintings Carr submitted to the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1911, such as Le paysage (which came to be known as Brittany Landscape), reflect these same features—compositional experimentation, dynamic and unexpected coloration, and a vast array of brushwork—as do the Fauvist-style works she exhibited in Vancouver the following year.

Early First Nations Themes, 1911–13

When Carr returned to Canada she resumed her travels and documentation project along the Northwest Coast of British Columbia. She also reworked in her new French style several earlier drawings and sketches of Aboriginal subjects. She made watercolours and drawings, field notes, and sketches that she could use later as source material for studio paintings.

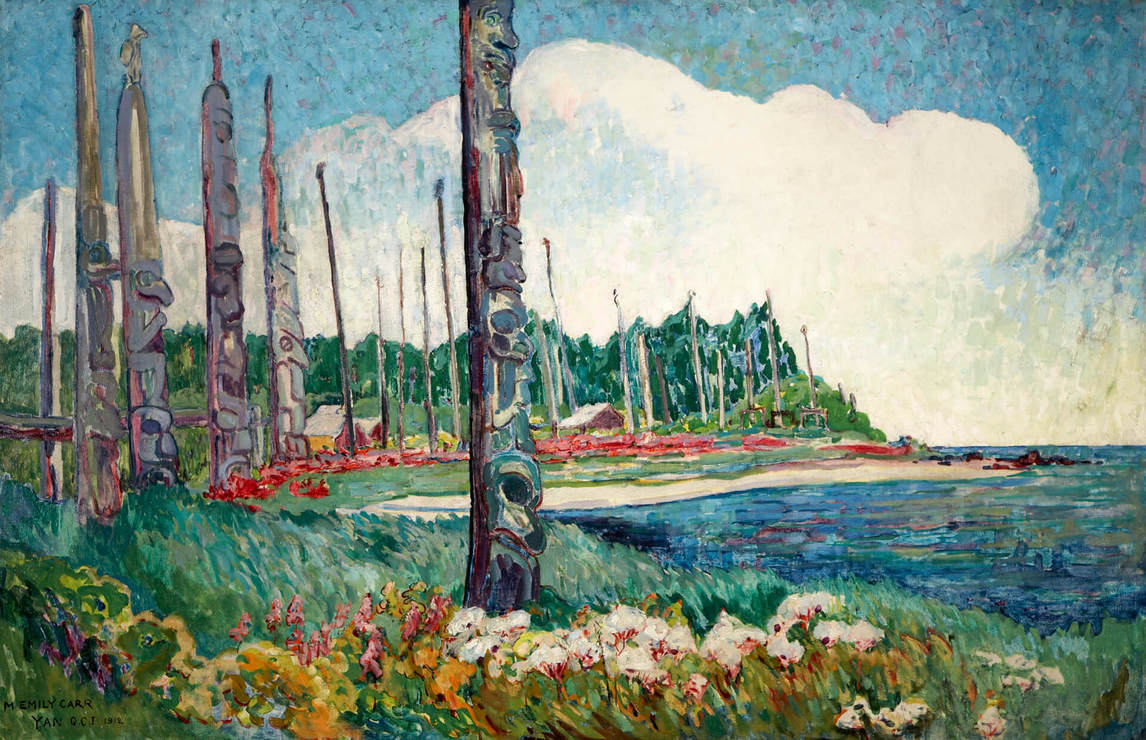

She occasionally used photographs in making her paintings, acquiring them from professional photographers or from her travelling companions, as the curators Peter Macnair and Jay Stewart describe in their project To the Totem Forests. As usual Carr worked en plein air, drawing and painting. Her subjects were single totem poles or figures, as well as village scenes. All were infused with the vibrant colour, active brushwork, and reduced form of the French school—as can be seen in Yan, Q.C.I., 1912.

At home in Victoria Carr produced mostly small-scale studio paintings in watercolour as well as oils. Unfortunately, her intense work from this period received little support, and, between 1913 and 1927, she produced few paintings.

Modernism and Later First Nations Themes, 1927–32

When Carr travelled to Ottawa in the summer of 1927 for the National Gallery of Canada’s Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern, the experience transformed her life.

Not only were her works well represented in the show but also she met members of the Group of Seven and other artists working in the modernist style. Lawren Harris (1885–1970) introduced her to theosophy—an esoteric philosophy with roots in Gnosticism that neatly mirrored the modernist preoccupations with the sublime and posited a universal experience in which spirit and matter were fused. Through Harris, her quest for a spiritual dimension to her work emerged as a central investigation. In paintings like Odds and Ends, 1939, she returned to her exploration of forest themes, both in their natural grandeur and in their despoliation by loggers. Ultimately, however, Carr found that she preferred the more personal God of her traditional religion to theosophy—a decision that strained her long-standing and warm friendship with Harris.

Between 1928 and 1930 Carr made her last excursions to the First Nations villages, returning to many of the northern sites she had visited decades earlier—the Nass and Skeena Rivers and Haida Gwaii, then to Friendly Cove, and finally to Quatsino. During these trips she produced many watercolours as source material for her studio works. First she made drawings in small sketchbooks, and from these she produced more resolved watercolours. She also experimented with charcoal drawings on manila paper, which reveal a new minimalist direction in her art and became the source of some of her major paintings of this period.

Carr’s strategy of developing her work from sketch to finished painting became much more remarkable during this period: as in Big Raven, 1931, the monumentality of the figure is reinforced through a more stylized treatment. Indigenous people no longer appear in the landscape, and the effect is to create a sense of mourning, ruin, and decay—stemming, in all likelihood, from the dislocation of the indigenous populations and destruction of the original sites since her earlier visits. By this time many poles had been dismantled and the villages left empty. Ethnologists, politicians, and the media of the day underscored the political urgency of her project and drove her to find the formal and artistic means to achieve it effectively. During this same period, however, Harris advised her to abandon Aboriginal subjects and to work directly with the landscape.

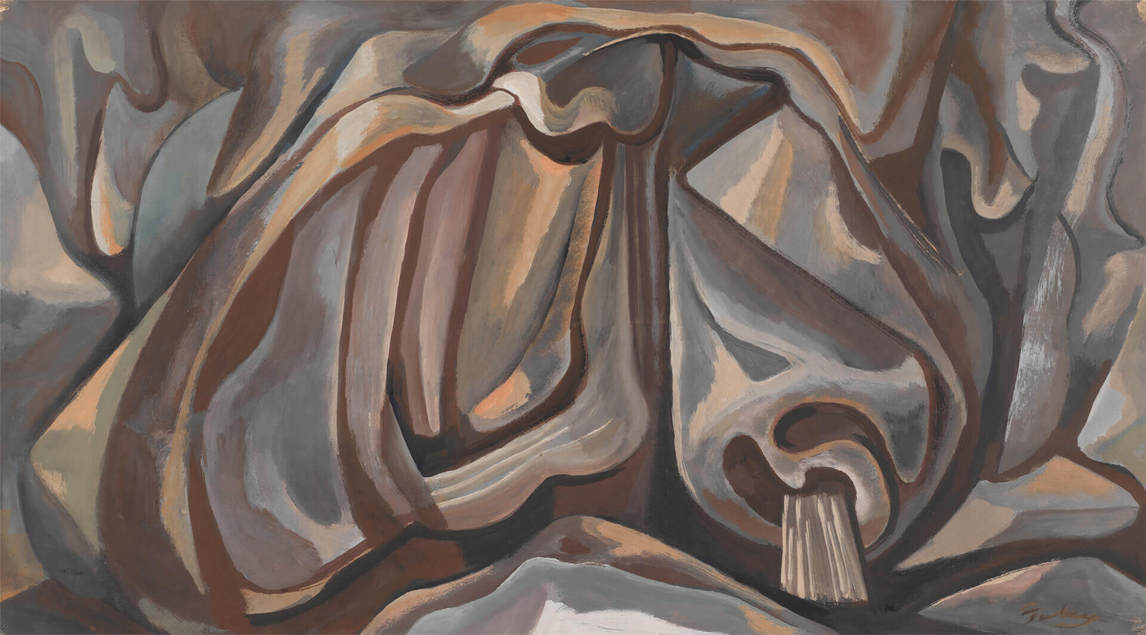

Landscape works of the time, such as Forest, British Columbia, 1931–32, reflect the elements that helped to shape her work: the teachings of the French schools and her observation of the work of indigenous artists, as well as Lawren Harris’s encouragement and influence. Her conversations at this time with the American artist Mark Tobey (1890–1976) also helped her to see the structure of the forest and to express it in her work.

The Forest, Sky, and Sea, 1933–37

The period from 1933 to 1937 marked a new focus for Carr’s work. Moving away from the iconography offered by the totems and carved Aboriginal figures, she returned to forest themes.

From 1932 on, Carr had begun to replace her watercolours on paper with a more expressive substitute that retained the chromatic and textural range of oil on canvas while using less-expensive means, as she did in works such as Sunshine and Tumult, 1938–39. She worked on paper and used gasoline to thin her oil paints, which resulted in a viscosity and density that still retained the ease of watercolour during her excursions. Initially she used these materials only for sketches for larger canvases, but by 1936 she was making finished works in these media. With this new technique she was able to demonstrate the powerful expressionistic forces she sought more directly.

In 1933 Carr purchased a caravan, which she called “the Elephant,” so that she could live in the forest near Victoria as she worked. For several weeks at a time she remained in places like Goldstream Park, where she felt great contentment. Sky, land, and forest are chiselled in her earlier forest paintings, the entire canvas fusing into a Cubist grid of interlocking planes or modelled lushly and organically into a kind of muscular, painterly draping. Paintings from the earlier period display the reduction of form that stems from the influence of Harris’s abstraction.

The simplification and unification of formal elements found in the isolation of a single tree, for example, was a result of influences from First Nations style and iconography. Carr created works that become contemplations on life and death, birth and decay. Although her painterly approach loosened and changed, the subject of the solitary tree persists with works such as, Scorned of Timber, Beloved of the Sky, 1935.

After 1933 Carr’s formal and spiritual concerns are fused with her concept of “unity in movement.” She writes,

I woke up this morning with “unity of movement” in a picture strong in my mind. I believe Van Gogh had that idea. I did not realize he had striven for that till quite recently so I did not come by the idea through him. It seems to me that clears up a lot. I see it very strongly out on the beach and cliffs. I felt it in the woods but did not quite realize what I was feeling. Now it seems to me the first thing to seize on in your layout is the direction of your main movement, the sweep of the whole thing as a unit. One must be very careful about the transition of one curve of direction into the next, vary the length of the wave of space but keep it going, a pathway for the eye and the mind to travel through and into the thought. For long I have been trying to get these movements of the parts. Now I see there is only one movement. It sways and ripples. It may be slow or fast but it is only one movement sweeping out into space but always keeping going—rocks, sea, sky, one continuous movement.

Carr continued to explore these spiritual forces aesthetically through her art. As she wrote in 1934, “What does spirituality in painting mean? First, the seeing beyond the form to the spiritual reality underlying it—its meaning. Second, the determination, power and courage to stick to the ideal at all costs, but there is a danger of letting the ideal become diluted with vagueness, uncertainty, indecision; then the thing is lost and left unsaid.”

In the later works the metaphysics of Carr’s quest combine with the foreboding elements of the land itself—the forests acting as an extension of her salvage paradigm. Already the effects of deforestation had become visible in British Columbia, and can be seen in such works as Loggers’ Culls, 1935. Here, Carr’s enquiry extends to the creation of a spiritual cosmology that encompasses forest, land and sea. She writes, “When I want to realize growth and immortality more I go back to Walt Whitman. Everything seemed to take such a hand in the ever-lasting on-going with him—eternal overflowing and spilling of things into the universe and nothing lost.”

Last Paintings, 1937–42

After her heart attack in 1937 Carr found that her health increasingly interfered with her ability to work outdoors in the landscape. Her last excursions took place in 1942. The works from these final years—such as Above the Gravel Pit, 1937, and Odds and Ends, 1939—emerge from the depths of the forest: light and the open sky play a greater role, and movement in nature is married to her brushwork. The static forms of earlier work give way to roiling, open mark making and loose passages of colour. These works are atmospheric, light, and vibrant and reference a wide variety of styles, from Post-Impressionism and Expressionism to painterly abstraction.

Carr’s spiritual quest for an overallness or unity in her canvases, a quest that would reflect her search for oneness in art and religion, became an expression of consciousness, life force, and spiritual energy in her final works. Rather than using the brush to describe volume and structure, Carr lets mark making itself become the subject. The fluidity of the oil-on-paper works comes to fruition in the virtuosity of the brushwork, as in Sombreness Sunlit, c. 1938–40.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements