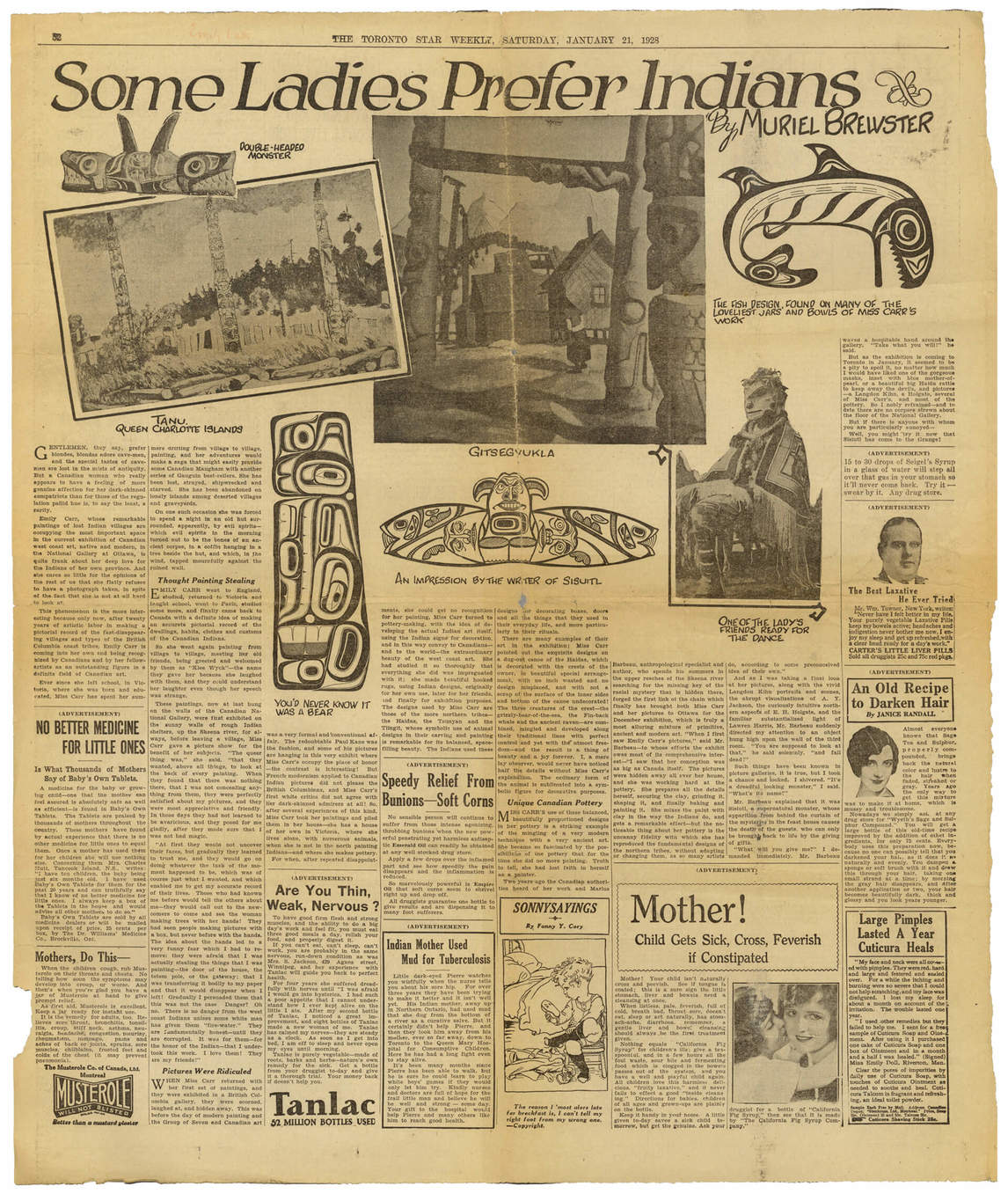

Emily Carr’s uniquely modern vision of the British Columbia landscape became associated with the articulation of Canada’s national identity in the early twentieth century. More recent critiques assess the work from a feminist and post-colonial perspective. Her work influenced how the West Coast has been imagined and expressed by subsequent generations of artists.

Subject Matter and Style

Emily Carr is one of Canada’s best-known artists. Her life and work reflect a profound commitment to the land and peoples she knew and loved. Her sensitive evocations reveal an artist grappling with the spiritual questions that the Canadian landscape and culture inspired in her.

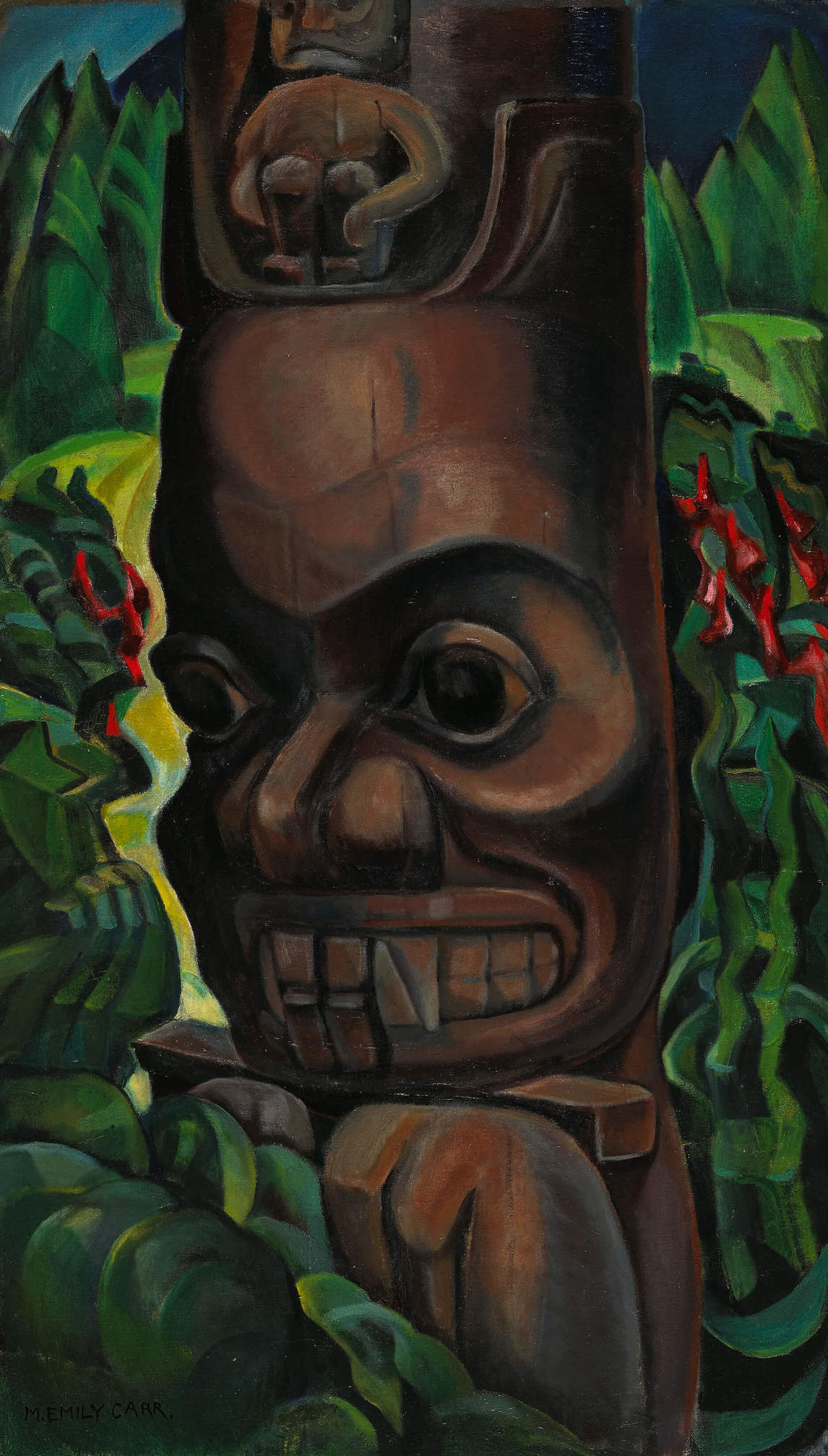

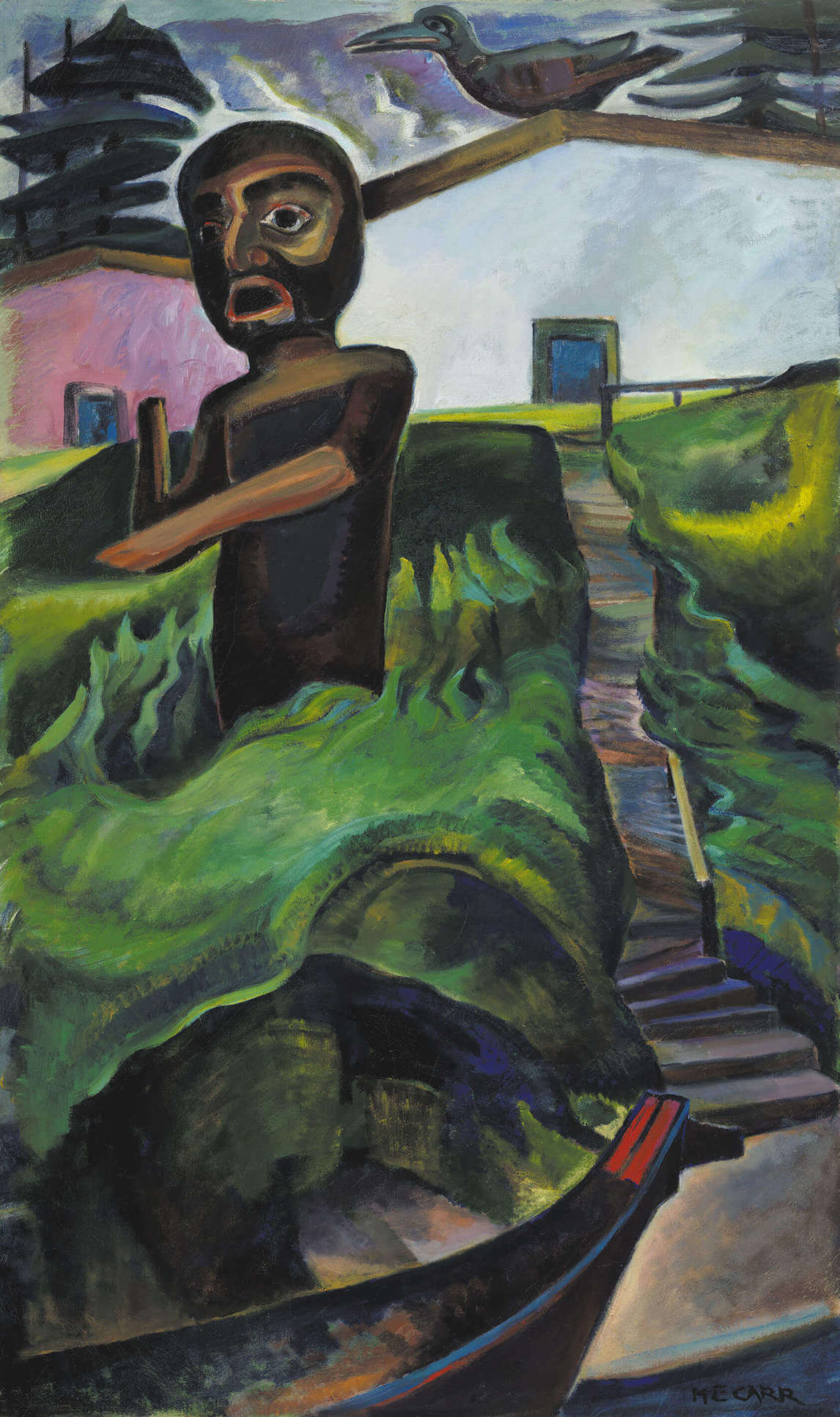

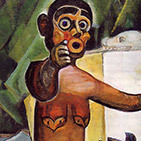

With such works as Big Raven, 1931, and Grizzly Bear Totem, Angidah, Nass River, c. 1930, Carr reframed existing First Nations iconography and developed her own imaginative vocabulary, thereby inventing an image system for the West Coast that embraced political, social, cultural, and ecological subjects in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Using the formal approach of modernism, Carr drew on the legacy of indigenous creators from the coastal area to build a personal language that reflected her powerful vision. Along with the Group of Seven, she spearheaded Canada’s first modern art movement.

Carr was shaped by diverse and sometimes conflicting influences. During her education in France, she came into contact with European modernity—specifically, Post-Impressionism and Fauvism and, later, elements of Cubism and German Expressionism. She found herself at odds with the imperialism that viewed indigenous culture as primitive. She had profound curiosity and respect—inevitably within the perspective of her own ancestry and times—for the cultural production of Aboriginal people.

Carr’s deep-rooted spirituality was drawn initially from her Protestant origins and later enriched by theosophy, Hinduism, and the transcendentalism of American poet-philosophers such as Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. All these influences led her to invent new forms of artistic expression—evident in her late paintings, such as Blue Sky, 1936—to reflect her creative vision of the B.C. landscape and what she saw as its spiritual and elemental force.

It was this vision that represented the first wave of modern art to emerge from the West Coast of Canada. As the contemporary Canadian artist Jeff Wall (b. 1946) describes her, Carr was an “originary force” of modern art in the West, “representative of traditions in which all of us who work here are in some way or other involved.” Wall’s acknowledgement of Carr’s influence attests to the continuing relevance of her work, its conceptual dissemination outside of national borders, and its legacy for contemporary artistic practices.

Modern Art and Nationhood

Carr’s work has also been considered revelatory in its depiction of the specific geographical, political, social, and psychic ruptures that emerged among indigenous, colonial, and migrant populations on the West Coast of Canada. These issues include the complex narrative of settlement and displacement—presented in works such as Vanquished, 1930—that marks Canada’s history and the way that preoccupations about land, its exchange, and its envisioning are used to express notions of who belongs on the land and who does not, and how these crucial struggles of belonging are articulated.

Emily Carr and the Group of Seven produced their work at the same time that industrialization and territorialization were shaping Canada as a nation. By evoking an “untouched” landscape, their works demonstrate emergent ideas of capital and property that were being explored and contested—a strategy that the Canadian art historian John O’Brian terms “wildercentric”—while both federal and provincial governments began to look for ways to define Canada as a modern nation. At the time they were painted, works such as Forest, British Columbia, 1931–32, were celebrated for their assertions of nationhood, a vision that assisted in furthering Canada’s postwar status on the international stage.

Feminist Issues

Carr’s career is notable for her ability to forge a career as an artist within a patriarchal society. In the late nineteenth century, women’s access to formal training in art was relatively new. In Paris the École des beaux-arts had been operating for centuries, but it did not open to women until 1897. The new private academies, Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi, accepted women around 1870, though the Julian intially charged them double fees. Carr’s peer David Milne (1882–1953) famously commented that he did not trust women’s art, and Harry Phelan Gibb (1870–1948), her tutor in France, corrected his declaration that she would be among the great painters of her day to say, instead, “great women painters.”

Carr was one of the very few women artists in this period who rejected the pastoral landscapes, domestic scenes, and portraits of mothers and children to seek out subjects with challenging political and ecological themes and cultural significance. Her powerful work Self-Portrait, 1938–39, painted toward the end of her life, is significant not only for the physical likeness she captures but also for the directness with which she paints her own image. In the same way that Carr sought to depict the spiritual forces in the landscape, her self-portrait is remarkable for the psychological insight it reveals.

Indigenous Influences

In her work Carr sought to make visible the powerful forces she witnessed both in the landscape and in the cultural production of the indigenous peoples of British Columbia. To do so was part of “the ambition of her work and its deep-seated quest for empowerment.”

Johanne Lamoureux, an art historian at the Université de Montréal, describes Carr’s preoccupation with and adaptation of the spiritual and talismanic purpose of totem poles in such works as Blunden Harbour, c. 1930. In her words, they became an “alibi” that allowed Carr access to a formidable visual language and its symbols:

The totem poles provided a departure point for a pragmatic alibi, for beyond their mythical content they allowed her to revive from painting to painting the powerful and troubling experience of each encounter, and to shock viewers in turn, all the while compelled, even exonerated, by the sincerity of the affect, by the truth of the impact she sought to render. And so she relocated the “fetish” in another religion, the new western religion of modern art in its romantic affiliation.

Lamoureux’s use of the term “fetish” is derived from Western traditions of psychoanalysis. It associates Carr’s adaptation and copying of First Nations creations that refer to specific spiritual elements—such as The Crazy Stair, c. 1928–30—as evidence of her belief in the transformative power of art on the viewer.

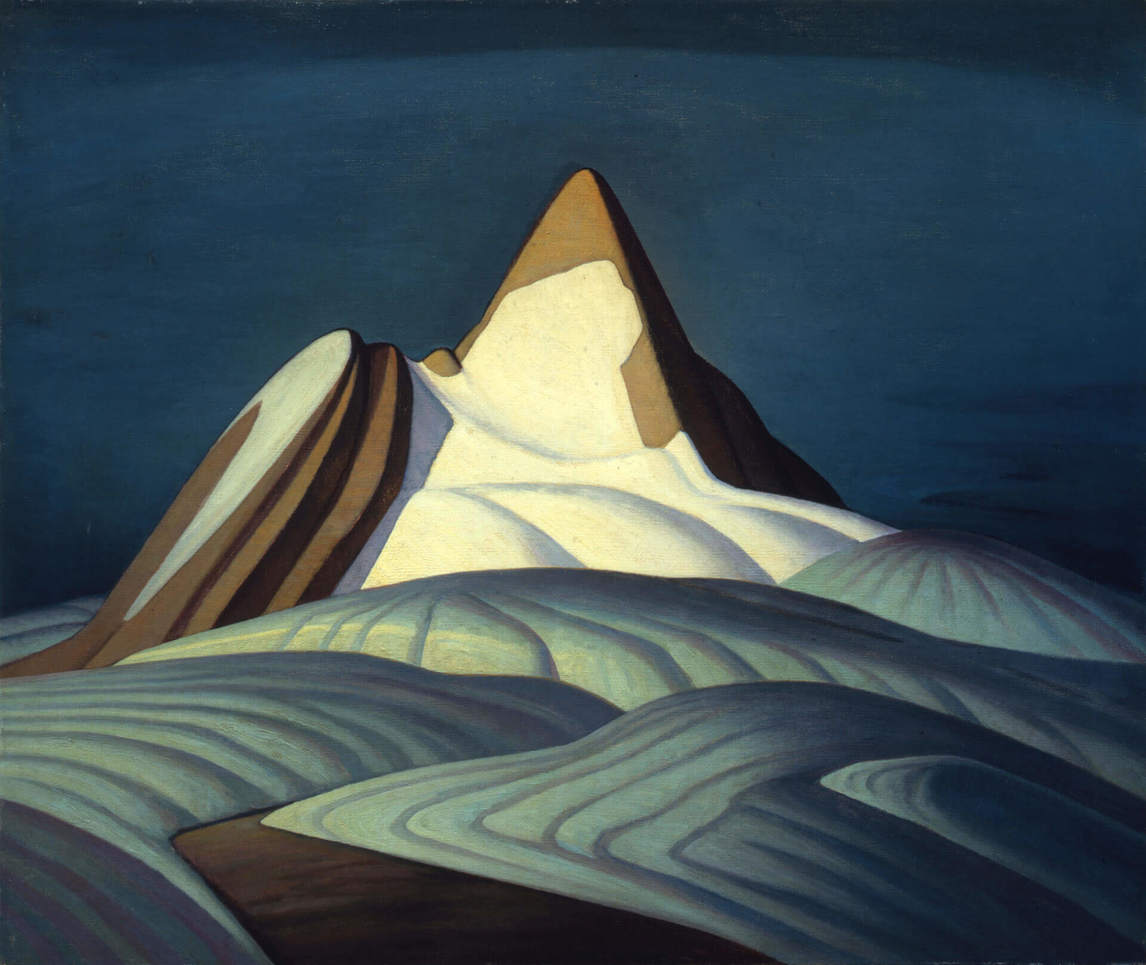

The Group of Seven

While Carr worked in relative isolation on the West Coast from 1904 until her death in 1945, the Group of Seven, men who were British immigrants or the sons of British immigrants, enjoyed regular support and patronage from collectors, critics, and curators as well as collegial encouragement from one another through critiques and conversation. Their paintings—such as Waterfall, Agawa River, Algoma, 1919, by J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932)—depict landscapes that, unlike Carr’s, are often empty of cultural signifiers and inhabitants or signs of industry and occupation.

Lawren Harris (1885–1970), the group’s most prominent member, was influenced in part by Scandinavian modernism, and he embraced its Symbolist and nationalistic renderings in works such as Isolation Peak, Rocky Mountains, 1930. In his words, “We [Canadians] are on the fringe of the great North and its living whiteness, its loneliness and its replenishment, its resignations and release, its call and answer, its cleansing rhythms.” The racial undertones of Harris’s address, although not directly intended, parallel the government’s policies of exclusion and suppression regarding Aboriginal peoples and non-white migrants—policies that were being implemented at the same time that the nation was cutting the imperial apron strings that tied it to Britain.

Following her participation in the National Gallery of Canada’s Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern and her meeting with Harris and other members of the Group of Seven, Carr felt emboldened to pursue a deeper spiritual dimension in her work. In paintings like Odds and Ends, 1939, she returns to her exploration of forest themes, both in their natural grandeur and in their despoliation by loggers.

Reception of Carr’s Work

Carr’s use of indigenous art forms in her paintings was criticized in the early 1990s through a series of post-colonial readings by indigenous artists and critics as well as art historians and scholars. In 1912, after Carr returned from her second trip to France, she determined to continue documenting the province’s “disappearing indigenous culture”—an aspiration she regularly proclaimed to her Aboriginal hosts—by painting its totems and villages, in works such as War Canoes, Alert Bay, 1912. She was sincere in this objective, completely unaware of her own internalized colonial response to indigenous cultures and its latent exploitative and romanticizing effect on her representation of Aboriginal life.

The public reception of Carr’s paintings during this period was embedded in the much wider “trafficking of Native images,” a phrase coined by art historian Gerta Moray to refer to the exhibition, promotion, and sale of cultural artifacts produced by First Nations peoples at world’s fairs and in tourist brochures and curio shops. At the same time that indigenous people were banned from taking part in traditional ceremonies, such as potlatches, or producing cultural objects for ritual purposes, Indian agents regularly donated confiscated artworks to public museum collections or to Canada’s world’s fair exhibits.

The British Columbia government also used images of indigenous artwork to promote the tourism industry abroad, proclaiming their exoticism while, simultaneously, the compulsory residential schools for Aboriginal children reinforced policies of forced assimilation. Government policies prohibited First Nations people from conducting their traditional ceremonies such as the potlatch or raising money to pursue land claims.

These policies of repression and dispossession from lands and customs had begun in the late seventeenth century on the East Coast, and they reached the West in the mid-nineteenth century. Their enforcement peaked during the first decades of the twentieth century as Carr undertook her work. Given this context, some Aboriginal groups and art historians such as Marcia Crosby and Gerta Moray in the 1990s included Carr in their criticism of colonial attitudes toward Canada’s indigenous people.

In the twenty-first century both the art world and the art market have become interested in artists working within modern practices but from locations on the periphery. The result has been a resurgence of interest in Carr’s work. This has been further underscored by the placement of Carr’s work within an international context at Documenta 13, where seven of her paintings were exhibited in Kassel, Germany, in 2012. Such new projects also serve to complicate the narrative of her life and work, framing her beyond national borders.

In 2014 the exhibition Convoluted Beauty: In the Company of Emily Carr at the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon re-examined Carr’s work in the context of Canadian and international contemporary artists exploring ideas of exile and displacement. Also in 2014 the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, England, in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario, mounted a solo exhibition of Carr’s work, From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia, the first in England since the exhibition held at Canada House in 1990. As a result of such projects, the sophistication and courage of Carr’s work has increasingly received the international acclaim and resonant critical reception it deserves.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements