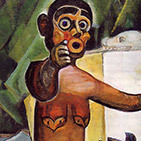

Vanquished 1930

Emily Carr, Vanquished, 1930

Oil on canvas, 92 x 129 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery

In Vanquished, completed soon after she painted Church in Yuquot Village, 1929, Carr uses a new, heavily modelled sculptural language to carve out a scene of desolation and ruin. As she explains in her autobiographical work Klee Wyck, in an abandoned village site “a row of crazily tipped totem poles straggled along the low bank skirting Skedans Bay…. In their bleached and hollow upper ends stood coffin-boxes boarded endwise into the pole by heavy cedar planks boldly carved with the crest of the little huddle of bones inside the box, bones that had once been a chief of Eagle, Bear or Whale Clan.” Carr’s salvage paradigm emerges clearly in both paintings.

In the 1930s displaced or commissioned totem poles were featured at world’s fairs and exhibitions as part of an emerging national vision for Canada; at the same time, a growing tourist economy sought to exploit traditional Aboriginal arts. By contrast Carr was determined to attest to the impact of colonialism on village life. The changes that the villages in the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii) had undergone since her first visits in the early 1900s, including the banning of potlatch ceremonies and the effects of clear-cutting, must have been evident to her. These paintings of the late 1920s and 1930s are invested with a quality of mourning that is both romantic and palpable. By this time Carr had also met the ethnographer Marius Barbeau and was aware of his statements on a “dying race”—a narrative in which the Aboriginal population was no longer seen as a threatening force to early settlers but as a vanquished and disappearing people.

Carr’s vision has been critiqued as a kind of idealized grieving. As the B.C. art historian Marcia Crosby writes,

Carr paid a tribute to the Indians she “loved,” but who were they? Were they the real or authentic Indians who only existed in the past, or the Indians in the nostalgic, textual remembrances she created in her later years? They were not the native people who took her to the abandoned villages on “a gas boat” rather than a canoe…. Her paintings of the last poles intimate that the authentic Indians who made them existed only in the past, and that all the changes that occurred afterwards provide evidence of racial contamination, and cultural and moral deterioration. These works also imply that native culture is a quantifiable thing, which may be measured in degrees of “Indianness” against defined forms of authenticity only located in the past. Emily Carr loved the same Indians Victorian society rejected, and whether they were embraced or rejected does not change the fact that they were Imaginary Indians.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements