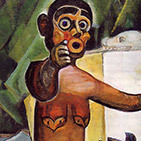

Self-Portrait 1938-39

Emily Carr, Self-Portrait, 1938–39

Oil on wove paper, mounted on plywood, 85.5 x 57.7 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

One of her few self-portraits, this work was painted around the time Carr turned sixty-seven. Although she had suffered a heart attack the year before, in 1937, the image presented is one of strength, confronting the viewer head on. The expressionistic quality of the work can be explained in Carr’s own words. “I hate painting portraits,” she said in December 1940. “The better a portrait, the more indecent and naked the sitter must feel. An artist who portrays flesh and clothes but nothing else, no matter how magnificently he does it, is quite harmless.”

The vibrant palette and expressionistic treatment that dominate Self-Portrait are characteristic of her work in the late 1930s. Here, however, the brushwork, instead of opening and loosening the subject, reveals Carr’s forceful nature as she scrutinizes the viewer—herself. As she writes, “To paint a self-portrait should teach one something about oneself.”

In the late 1930s Carr’s work becomes increasingly abstract—a culmination of her abilities in design, imagery, gesture, and tone and an attention to both positive and negative space, which she uses metaphorically and formally. Increasingly expressionistic, sensual, and embodied, paintings such as Blue Sky, 1936, and Dancing Sunlight, c. 1937, take the expressive brushwork of the earlier paintings even further, almost completely fragmenting the image to create an open, vibrating treatise on the life force she imagined in these forest spaces.

Ultimately, Carr found that the subjects that captured her imagination were to be found in the solitary spaces—the blank canvases—onto which she pursued the larger existential preoccupations that returned to her persistently throughout her life. As Carr writes: “Spirit is undying life. Life is always progressing. The supreme in painting is to imitate that spiritual movement, the act of being.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements