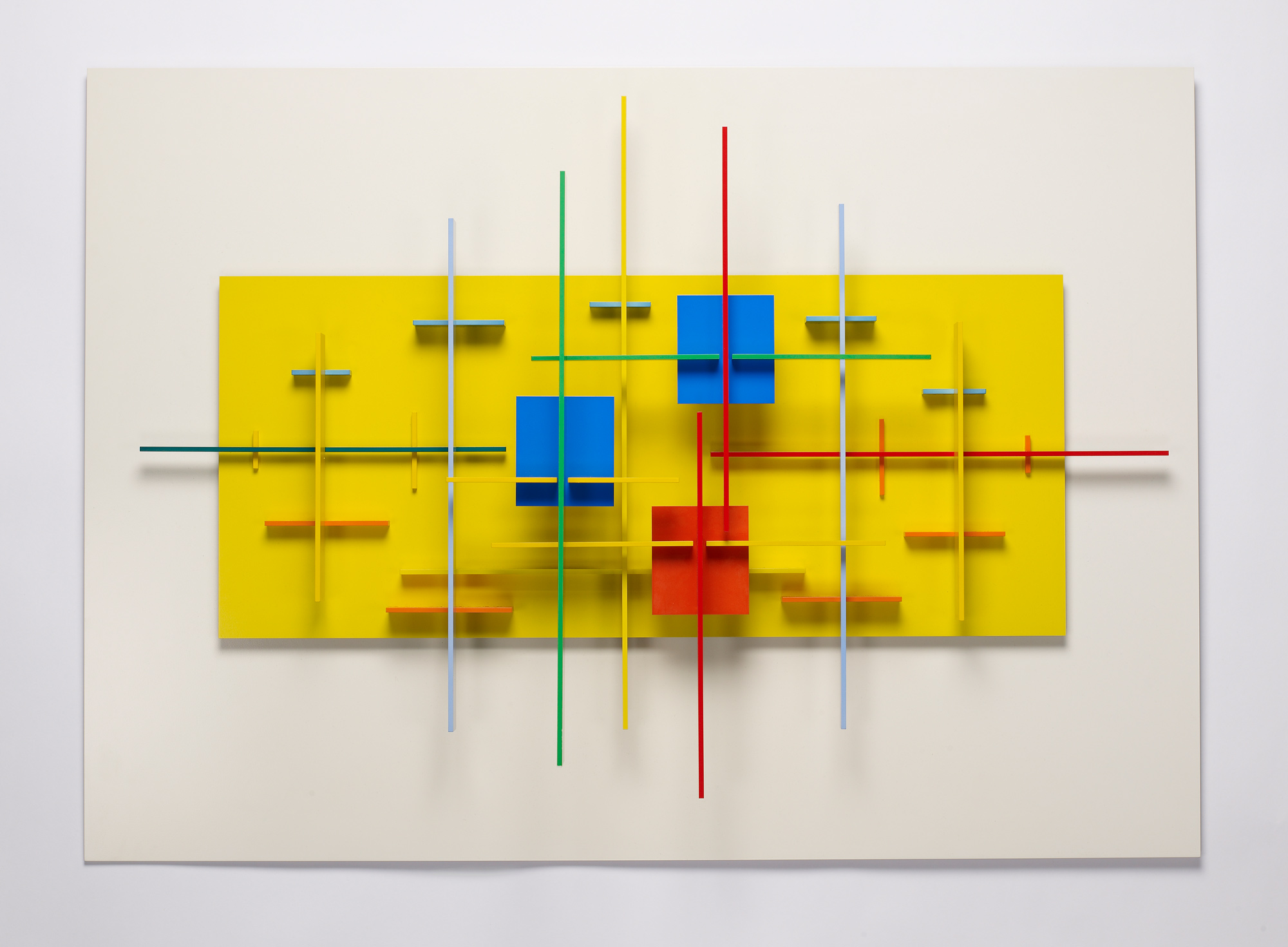

The primary contribution that Eli Bornstein made to abstract art in Canada was his development of the Structurist Relief: a singular art form that draws from both painting and sculpture. The innovation lies in Bornstein’s approach, freeing abstract painting from the restrictions of the flat picture plane, and advancing it into the real, three-dimensional space of sculpture. His reliefs are built using colour blocks and planes that are activated by ambient light and meticulously choreographed by the artist into a dynamic organic unity.

Painting into Relief

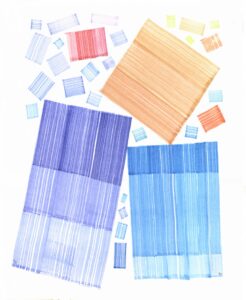

As a student, and during his early career, Bornstein worked in the traditional media of printmaking, drawing, painting, and sculpture. In his painting, he systematically incorporated lessons learned from early twentieth-century European modernism; from Impressionism’s emphasis on the transitory effects of light; from Post-Impressionism’s focus on form and structure; and from Cubism’s radical deconstruction of the figure-ground relationship. Streetscapes such as Downtown, 1954, and Porte St. Denis, 1954, may be vibrant with energy, but they are also tightly ordered constructions of colour swatches and tilted planes that echo works by French Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Cubists like Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956). An example of Feininger’s work that may have influenced Bornstein is Cathedral (Kathedrale) for the Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar (Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar), 1919. As to landscapes, Bornstein’s watercolour The Island, 1956, takes its cues from Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) from the moment when the Dutch painter was turning toward pure abstraction. Bornstein looked particularly at Mondrian’s 1917 series Compositions with Color Planes, learning from them to disperse his own shimmering patches of colour flatly across the whole of a white sheet of paper.

In 1957, after a crucial meeting with American relief artist Charles Biederman (1906–2004), and after a sabbatical trip to Europe to meet a host of prominent abstract, geometric-relief artists such as Jean Gorin (1899–1981), Mary Martin (1907–1969), Victor Pasmore (1908–1998), and Georges Vantongerloo (1886–1965), among others, Bornstein largely abandoned two-dimensional media. Instead, he began to construct his first Structurist reliefs, an art form he has continued to develop throughout his career. Like Biederman, and unlike the Europeans, Bornstein insisted that art, even abstract art, should remain rooted in the close study of the phenomena of the natural world.

The Structurist Relief can thus be understood as a continuation of the tradition of landscape painting. But it does not transcribe or represent nature. Rather, it translates our experiences of the natural world into a new, parallel abstract language. In his article “Art Toward Nature” (1975–76), Bornstein spelled out the physical distinctions between traditional two-dimensional painting and the Structurist Relief. Whereas a painting hangs flat on the wall, a relief projects out from the wall into real space; that is, into the space of the viewer. Whereas the image in a painting remains unchanged regardless of where the viewer stands, the colours and structural relationships in a relief continually change in response to the viewer’s movements and angles of perception. Whereas a painting remains static, a relief unfolds as an ongoing dynamic event.

But, we may well ask, if “Nature” (as Bornstein often capitalized) is the subject matter, how can a reductive artistic vocabulary that is hard edged and geometric embody nature’s abundance? In a journal entry, Bornstein posed the question this way: “How can an art (the art that I practice) that so often seems and is so mistakenly regarded as almost high-tech—involving as it does drill presses, air-compressors, computerized milling machines, industrial materials like aluminum, plexiglass and acrylic enamel—relate to nature, its preservation and conservation? How does an art that looks so engineered, ‘foster increasing reverence for Nature in its broadest and deepest sense?’” Would it, on the contrary, he asks, be more relevant and meaningful if his medium “were mud or sand,” or if it “were fabricated with fur and feathers?”

But Structurist art is not about the touchy-feely or about tactile sensibility. Instead, Bornstein harnesses technology to finesse his expressive means. Industrial-type manufacture yields precision and clarity so as to purge the structural components of traces of the handmade. It allows material substance to be dissolved into colour phenomena. To compose with colour and light, and space and structure, in Bornstein’s words, is like performing “a multi-spatial visual choreography of chromatic and structural counterpoint”; it is like enacting a piece of music or performing a feat of choreography. The effects can be as delicate as “the winged color of birds and butterflies” or dramatic like music unfolding from intimate chamber performances to the magnitudes of symphonies and operas: “great polyrhythms, collisions, silences, repetitions and variations.”

Toward Construction

At the beginning of his career, Bornstein, alongside drawing and painting, also made sculpture. He carved in wood and stone and made small constructions—such as Shelomo, 1949–56—often with an eye to the work of Romanian artist Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957), his formal reductions, his sensitivity to materials, and the care with which he crafted his bases.

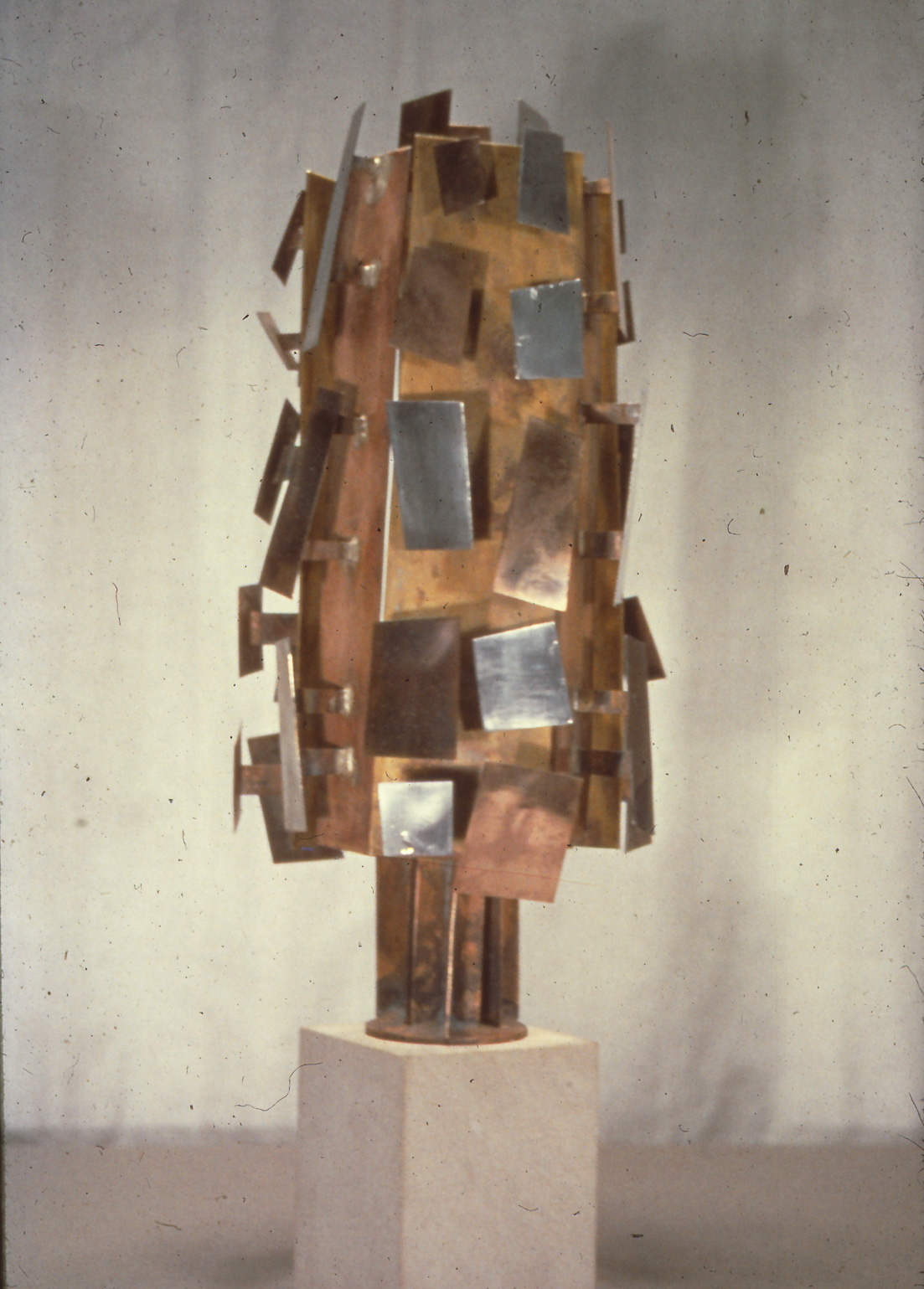

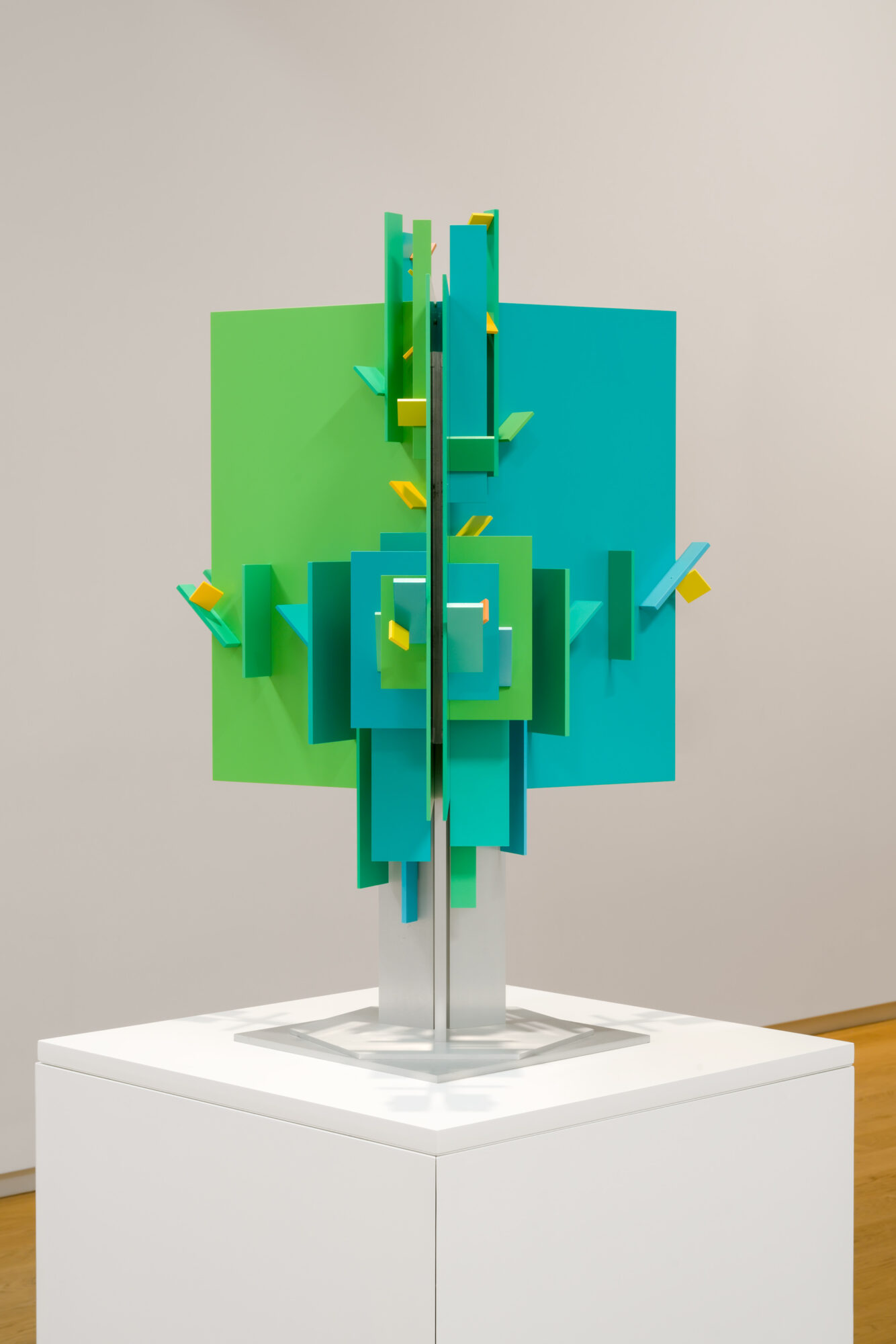

Growth Motif Construction No. 3, 1956, is both a self-sufficient work as well as a predecessor, or an early model, for his public commission Aluminum Construction (Tree of Knowledge), 1956, the monumental 4.5-metre-tall welded aluminum sculpture that had been commissioned for the new Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation Building in Saskatoon, and was completed later that year. Growth Motif bears witness to how Bornstein, while testing out new ideas, was evolving from a carver into an assembler, from a sculptor of mass to an openwork metal constructor, thus initiating an important stage along his journey to the Structurist Relief. Growth Motif was executed during a stay in New York, while Bornstein was at the Sculpture Studio in Long Island City, Queens. He was already adept at working with brass and bronze, materials he had learned how to handle in jewellery-making classes at Milwaukee State Teachers College in the 1940s, but the Sculpture Studio offered other techniques and new materials. Also while in New Jersey, he learned at a factory how to weld aluminum, a still relatively new technique for artists.

In Growth Motif, Bornstein thrusts his light reflective metal planes vigorously outward from a sturdy inner core. Through subsequent models, the core cedes its mass until it dissolves into an open metal construction, the configuration of which, as we will remember, he had earlier envisaged in the skeletal building structures in the lithograph Porte St. Denis, 1954, and which is ultimately fulfilled in Tree of Knowledge.

Tree of Knowledge, with its grand concatenations of reflective aluminum plates, large and small, and its intricate internal scaffolding, is a Constructivist sculpture. It is not yet a Structurist one. It’s a Cubistic abstraction, the free-floating shimmering planes of Bornstein’s watercolour The Island, 1956, here extruded as aluminum plates. It is the geometric equivalent of the conical shape of a coniferous tree with its tiered and drooping branches, now formally reconceived. Even so, some of the key ingredients of Structurist reliefs are already here: how the sculpture is built by construction and energized by light. But to cross the threshold from making abstract art based in nature to inventing a new vocabulary that would act in parallel to nature’s vital processes necessitated not another incremental move, but a restart from ground zero.

Structurist Art

In his conception of the Structurist Relief, Bornstein wanted to invent a purely abstract vocabulary that could still incorporate our immediate experiences of nature. This required him to restart from the point where Piet Mondrian had divorced his art from nature and crossed the threshold into pure abstraction. During his sabbatical leave in Europe in 1957, Bornstein set out to meet a number of artists working within the orbit of Mondrian’s De Stijl traditions. Their work indeed provided foundational principles on which he could build his own “New Art” (soon to be renamed the Structurist Relief). But he also found their work too rationally self-contained, reconfirming a conviction that he shared with his American colleague Charles Biederman that art should found its operations on the evidence of our visual senses. The future of Structurist art therefore should depend on its artists ever honing their observations of the natural world and painstakingly learning how to translate nature’s interdependent forms, colours, spaces, and light into abstract relief constructions.

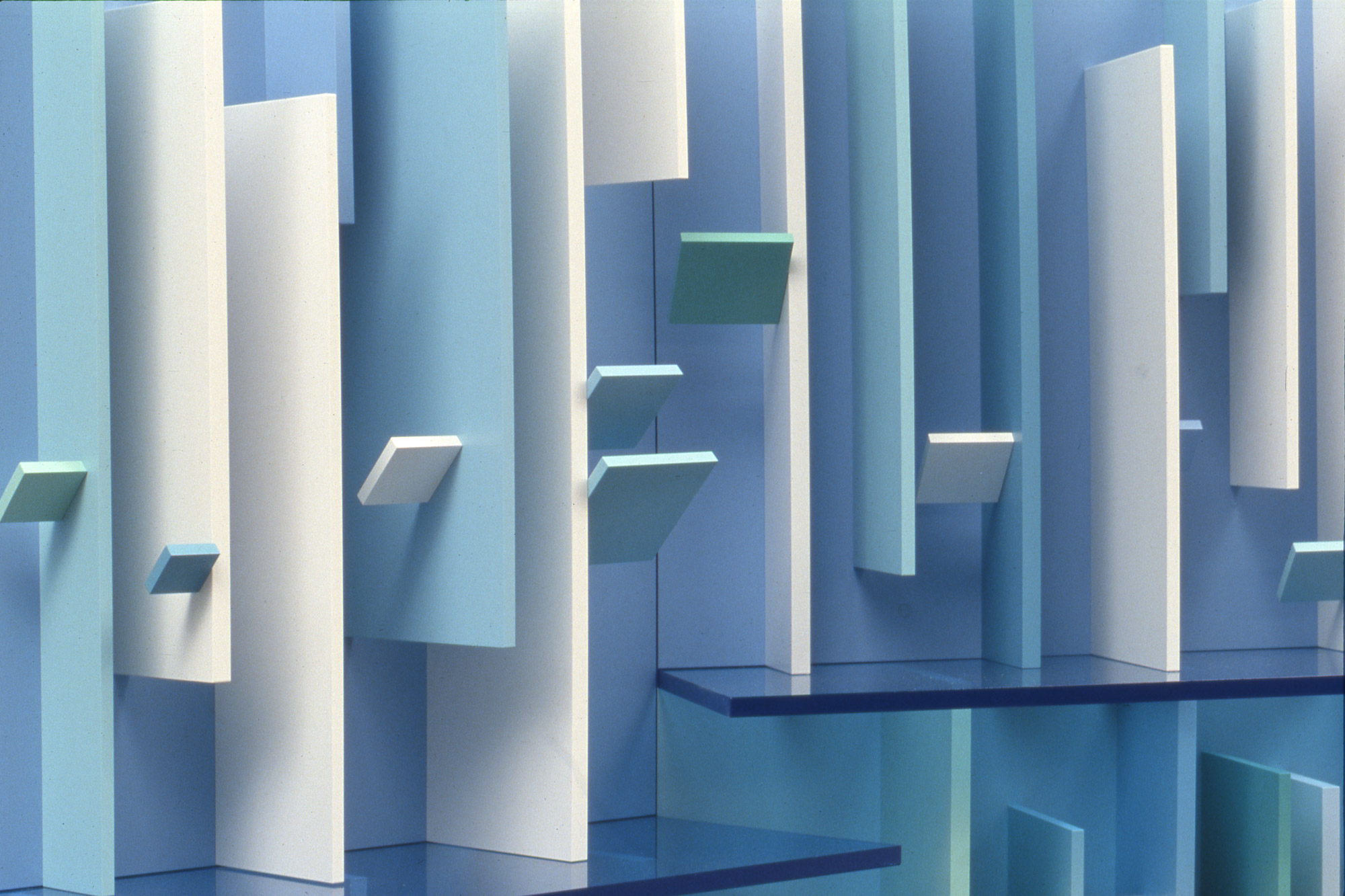

Bornstein’s early reliefs, such as Low Form Relief No. 10, 1957, are shallow projections and white with a few primary colours. He worked out their structure in smaller models (tempera on composition board), executing the final versions in oil on wood. The individual relief planes are quite large, often splayed out in asymmetrical compositions, engaging the full surface of their background supports, out to their very edges. Because they are mostly white, they can look a little puritanical, but there is also wit in their asymmetries and in their shadow play. By the early 1960s, the relief elements in works such as Structurist Relief No. 1, 1966, become more differentiated, thinner and deeper, their relationships more complex and their colours more active, their hues venturing beyond the primaries.

It may be simplifying a little, but something crucial happened around 1965 and 1966 in Bornstein’s evolution, quickening his work toward new expressive potential. Heretofore, Bornstein had used his ground planes more like neutral backdrops against which to stage the main action of the foreground relief constructions. Concomitantly, the reliefs had also tended to shy away from the edges of their supports, leaving them centrally clustered and self-sufficient, somehow independent from their backgrounds. This was, after all, the modus operandi of most Constructivist reliefs at the time, including Biederman’s own Structurist work.

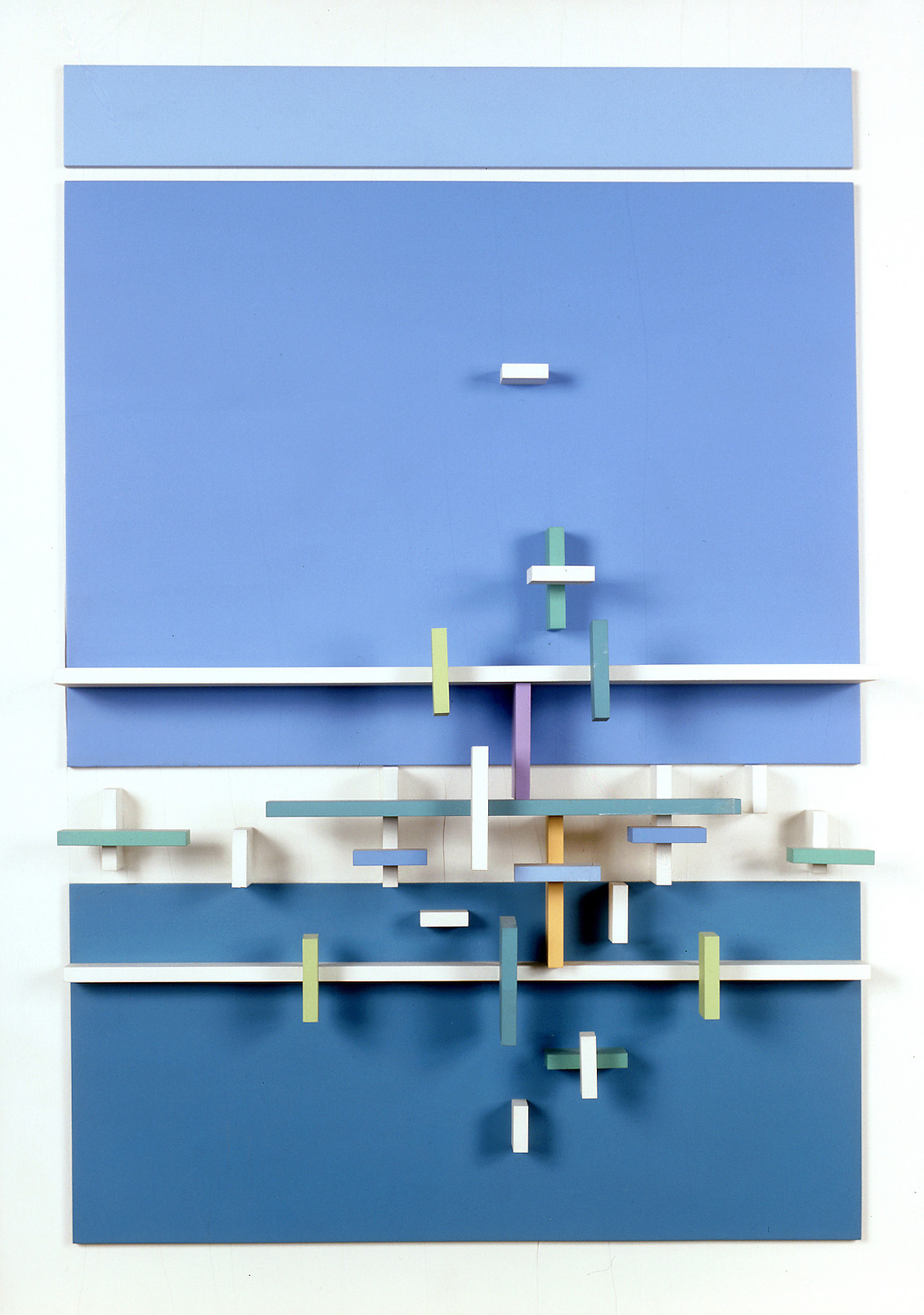

When Bornstein first introduced broad, flatly applied colour planes—like those blue ones, dark and light, in the sprightly Structurist Relief No. 1-1 (Sea Series), 1966—they were perhaps simply more relief components. But they perform differently. They sit flush to the surface of the support, reinforcing its planar spread. They are engaged formally, chromatically, and expressively with the relief components in front of them. But they also stand apart because of their expanse, and because of the outspread of their colours. They are slow and measured in contrast to the bustle of the foreground assemblages. Here it is as if Bornstein sets out to juxtapose two different zones of perceptual experience, two independent dimensions of time and place.

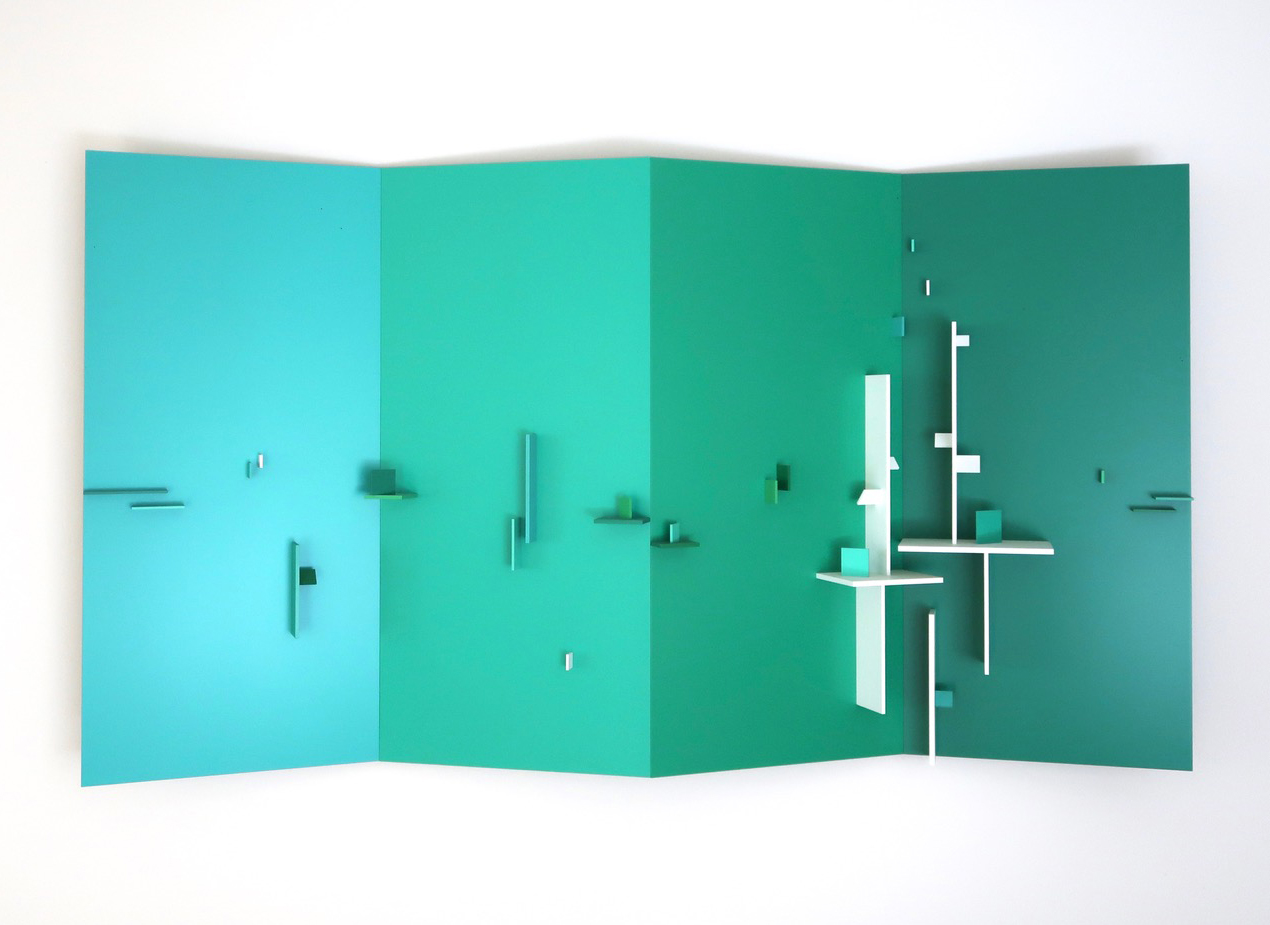

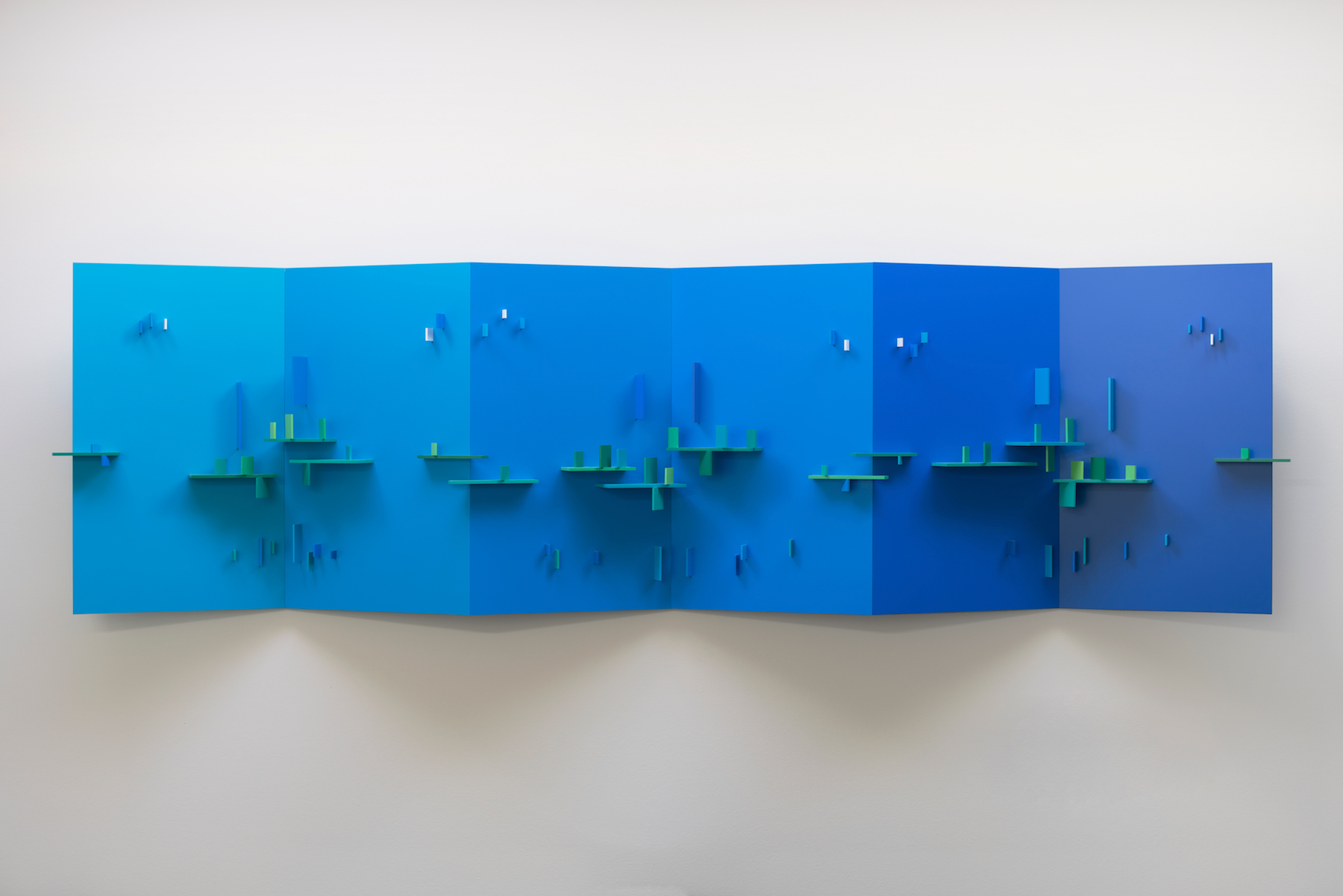

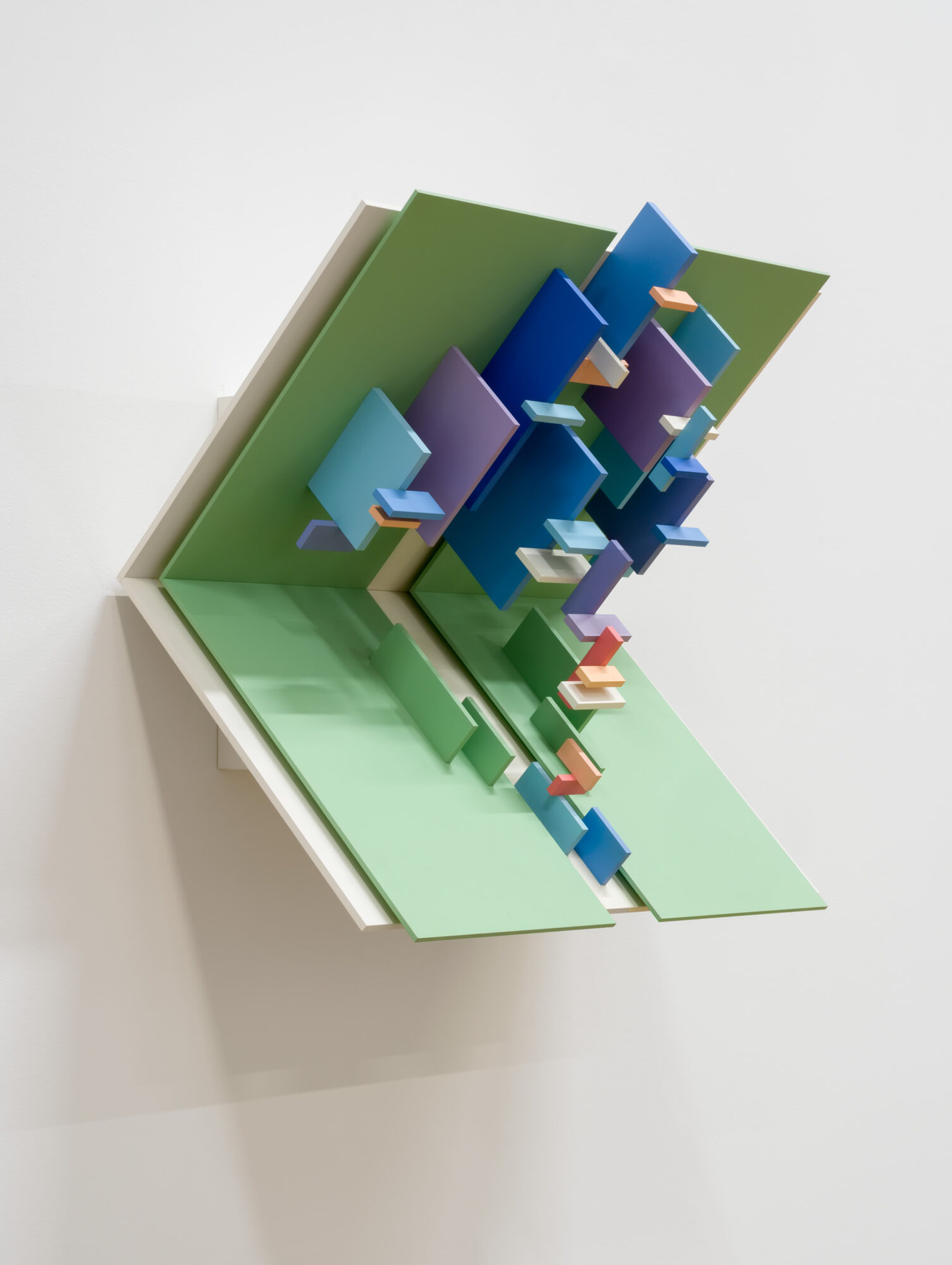

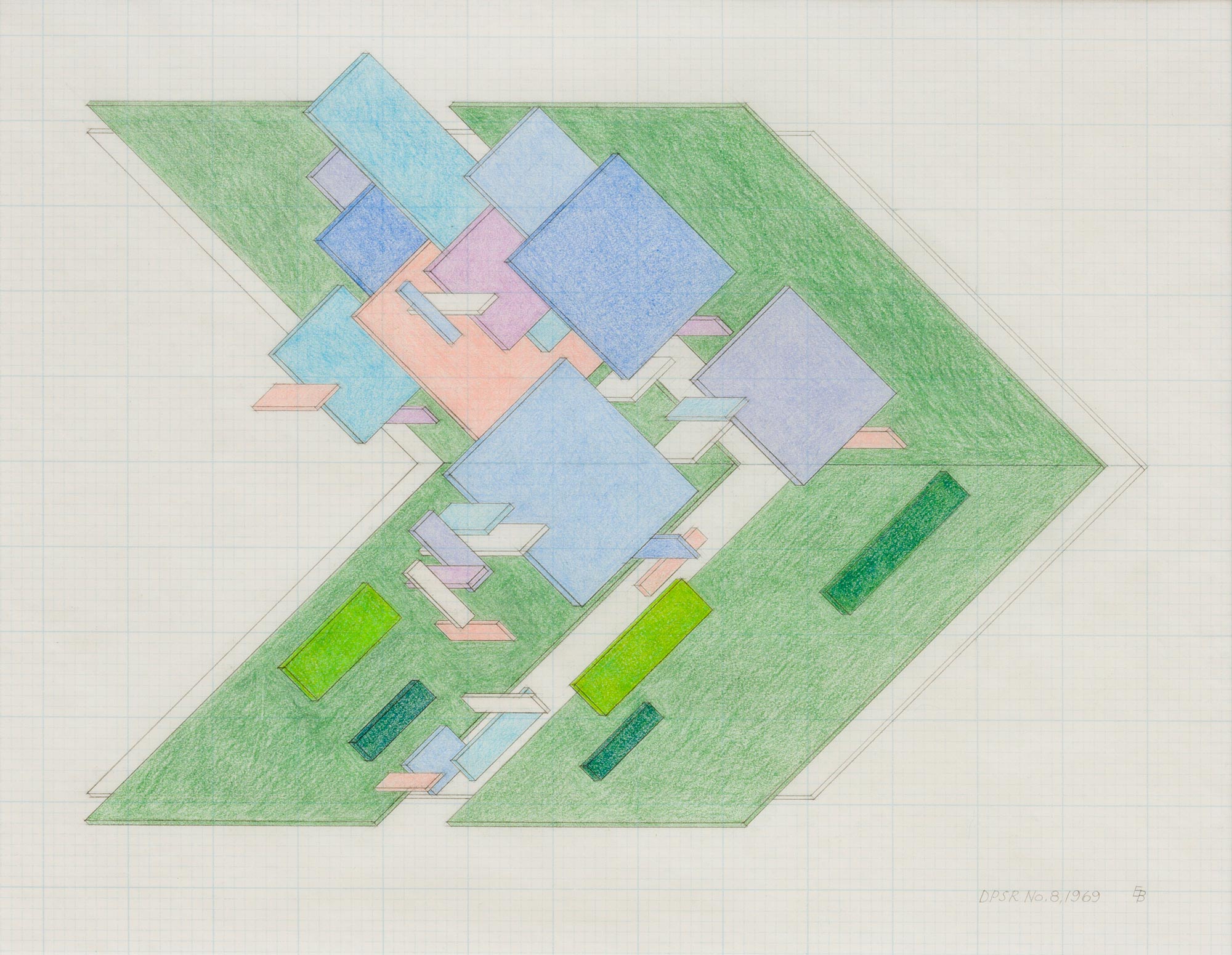

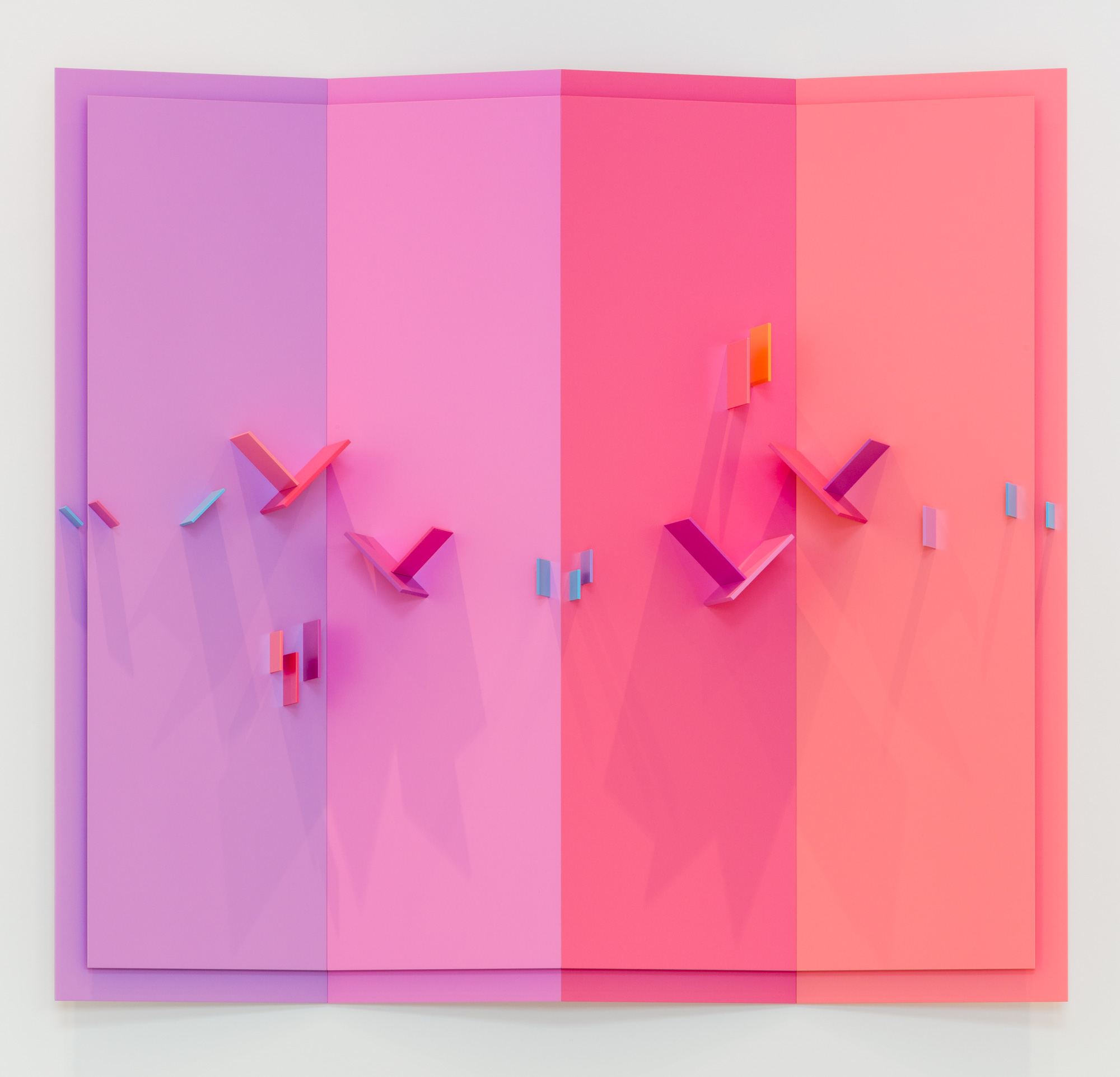

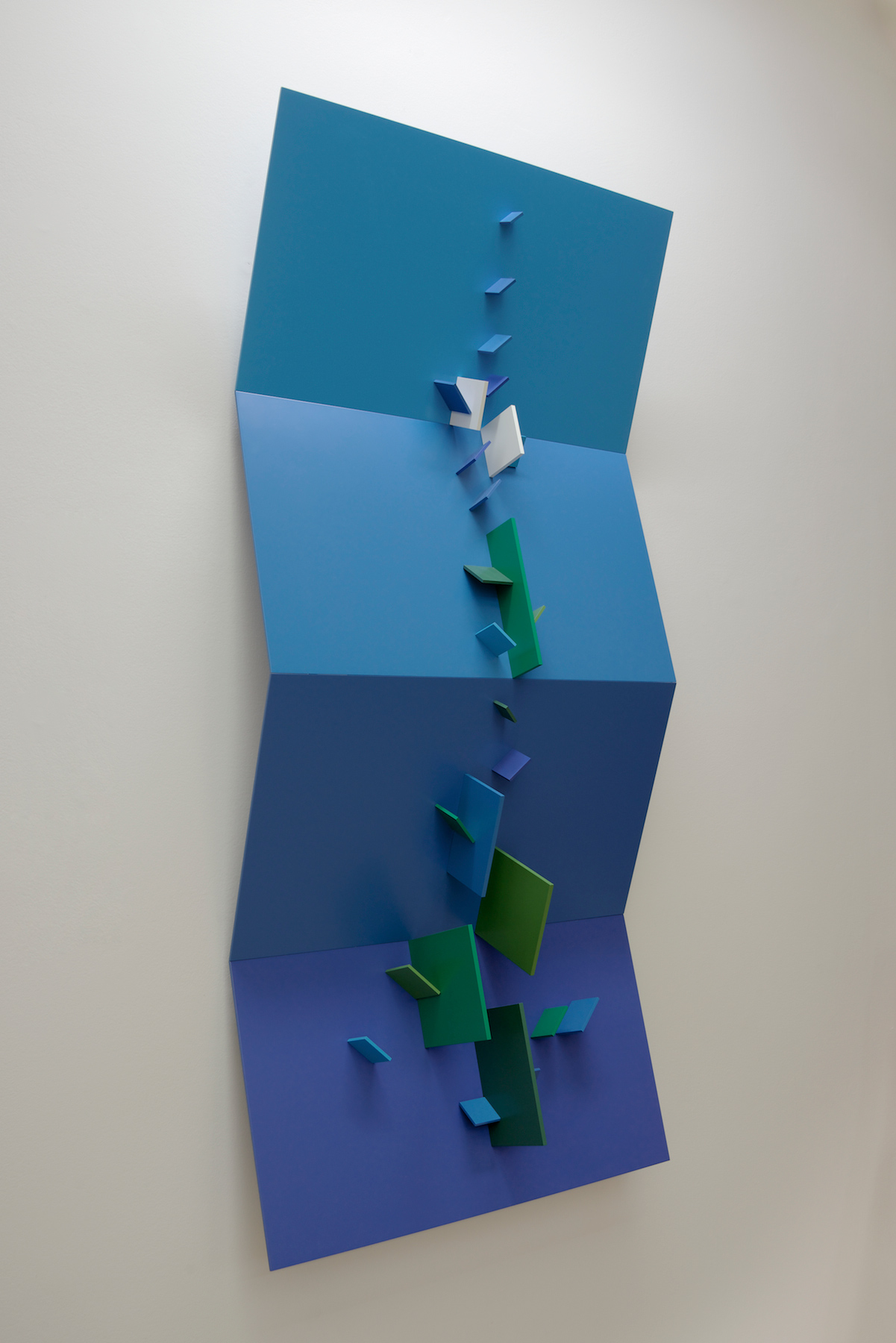

In another way, Bornstein complicated his figure-ground relationships when, in 1966, he folded the ground planes of his reliefs to make works like Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 8, 1973, presenting them vertically or horizontally, like half-opened books, their spines flat to the wall, the relief events with their play of light and shadow nested in their intimate 90-degree crevices. But the real potential of the colour-ground planes would flourish with the Multiplane Structurist reliefs, the Quadriplanes and Hexaplanes (literally, four and six planes) that he began in the late 1980s, and which would become the culminating achievement of Bornstein’s long and creative career, their voices increasingly spacious and resonant.

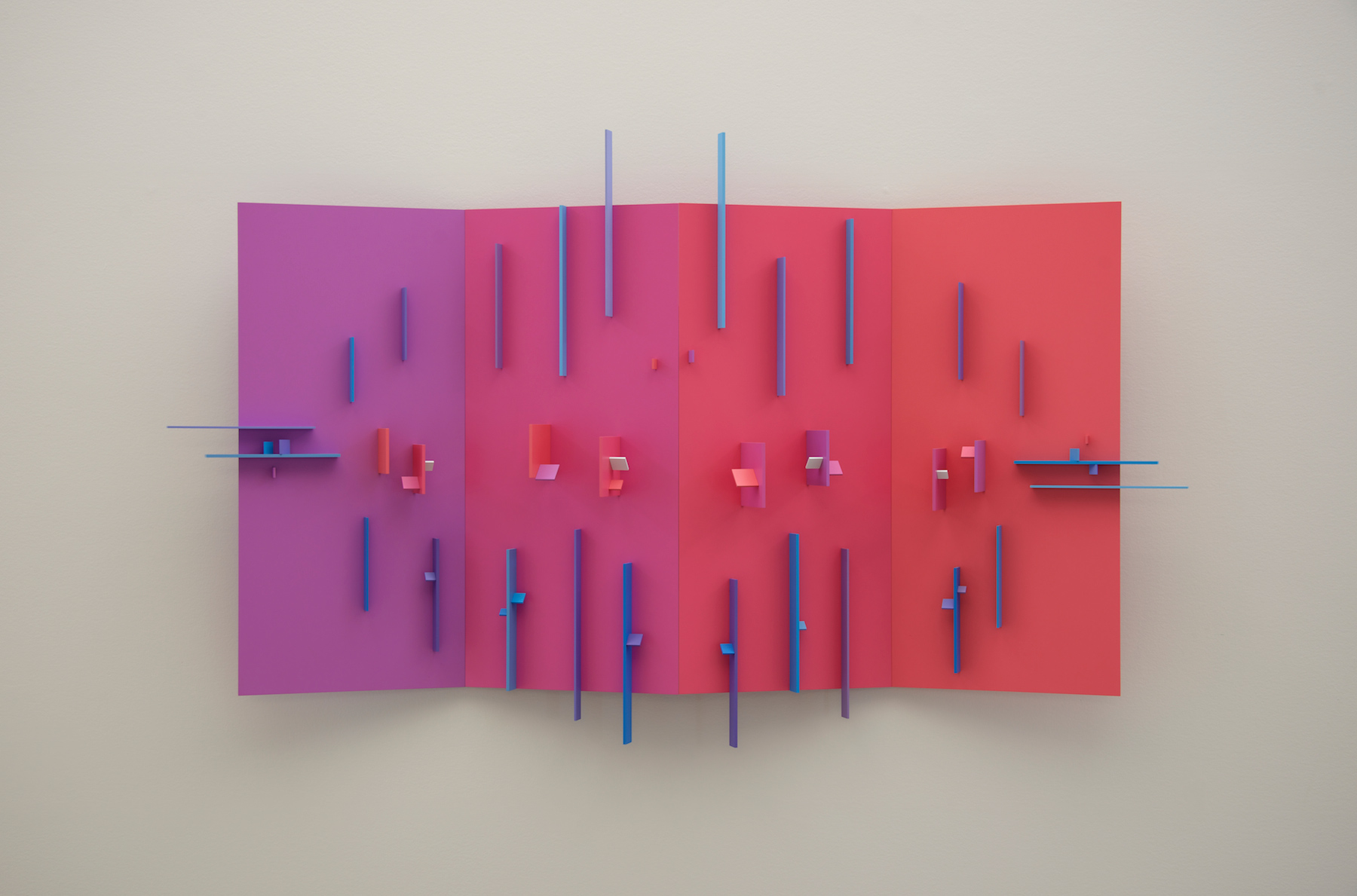

In the Multiplane reliefs, the ground planes zigzag slowly and majestically, each undulation marked by a finely tuned shift in colour gradation. In Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 4 (Sunset Series), 1997–99, a progression of mauves, reds, and oranges act like little jump-cuts in the continuity of time, as our eyes scan the horizon of their panoramic sweep. As the foreground relief articulations become more sparsely dispersed, their colours and shapes catching the light and throwing shadows, the ground colours deepen their stillness and widen their compass implicitly to extend far beyond their outer edges into a space of timelessness. Simultaneously, in the foreground, the ephemeral life of nature performs regardless. Another development was the free-standing Tripart Hexaplane Constructions, built from three double-plane reliefs backed onto one another, and raised on a slim aluminum pedestal.

Materials and Processes

For Bornstein, a new work can emerge in any number of ways: with an idea, a gesture, or a feeling. It can start with a drawing, a painting, or some elementary construction. Colour and spatial relationships may be worked out in sketches or in three-dimensional drawings or models. The process is always one of trial and error. “Regardless of how one begins, it rarely develops as one anticipates or intends,” as he reminds us in his journal. There are always, from beginning to end, new and unforeseen qualities to negotiate.

The early reliefs, such as Structurist Relief No. 22, 1959, were oil on wood. These he constructed at home in his studio using standard tools and materials—saws, a drill press, screws, etc.—and his own carpentry skills. Wood, however, posed problems, because with time and changing temperatures it would crack (or check) and show grain, compromising its intended look of technical anonymity. By the mid-1960s, Bornstein stopped using wood in favour of aluminum and Plexiglas, which both delivered smoother surfaces and were lighter and more permanent. For similar reasons, he replaced oil paint with enamel because it was shiny, clean, and reflective. The enamel is applied with a spray gun in order to obtain as immaculate a surface as possible.

It was during his Arctic travels in 1986, especially when fascinated by the crisp clarity of the reflection of icebergs in water, that Bornstein became alert to another potential of Plexiglas. Back in the studio in Saskatoon, in works that would evolve into his Arctic Series reliefs, he found he could use not only clear but also coloured Plexiglas to convey his experiences of the iridescence and the brittleness of the icy Ellesmere Island landscape. Plexiglas is transparent, as he explained in 1987, so it “not only colors the space and forms around it, but reflects the structure in depth, as well as seeming to extend the work beyond its physical limits.” Despite its expressive virtues, however, Plexiglas also had its limitations. Unlike wood it didn’t check, but it was subject to cracking from impact, especially in transport. There were also impracticalities in that the material was only available in a limited number of colours and, because it could be purchased in just one size—4-by-8-foot sheets—there was too much waste.

In the end, Bornstein’s materials of choice became aluminum and enamel paint. However, working with aluminum also required specialized skills and equipment, all of which he did not have, especially as his reliefs grew larger. He therefore started to work with professionals in a machine shop at the University of Saskatchewan’s engineering department.

-

Eli and Christina Bornstein in the artist’s studio, date unknown, Saskatoon

Photograph by Oliver A.I. Botar

-

View of Eli Bornstein’s studio featuring a collection of colour swatches for enamel paints, date unknown, Saskatoon

Photograph by Oliver A.I. Botar

-

View of Eli Bornstein’s studio featuring an unpainted aluminum Structurist relief, date unknown, Saskatoon

Photograph by Oliver A.I. Botar

Bornstein would begin the process of working out a new idea for a relief in his home studio. On a pre-ordered blank aluminum quadriplane or hexaplane support he would start to compose, using coloured papers and woodblocks. He would paste pieces of coloured paper directly onto the flat planes in order to determine his background colours, and onto individual wooden blocks, of various sizes and shapes, that he would position on top of the background plane as he experimented simultaneously with formal and colour relationships, and with the play of light and shadow. From this he would develop a plan for the relief from which the machinists would manufacture the individual relief blocks and drill the holes where they would be screwed on. The screws were countersunk to leave no visible trace of the manufacturing process.

The parts would then be sent back to Bornstein’s studio, where he would paint the individual parts and assemble them. Colours would be selected from the enamel paints commercially available or be supplemented by others that Bornstein meticulously mixed himself. At this final stage—because there were only so many coloured papers to choose from—adjustments could be needed to find the perfect final colours and colour relations. At first, he applied his paint in a spray booth in the basement of his studio, and then later, in an auto-body shop. Completing a work was a lengthy and time-consuming process, reflected in how Bornstein’s reliefs are often dated to a time span of several years.

But when is a work really complete? To answer, Bornstein turns to the viewer to remind us, as he does in a journal entry: “Finished works are not finalities but works-in-progress,” open-ended to allow for continually new completions in the “perceptions and interpretations” of their audience.

At the Mercy of Light

Light is indeed the great transformer, the bringer of light and illumination. It is the “Destroyer and Preserver,” the great artificer, of form and structure. Light is the guardian of the spectrum of color and all its grandeur.

An Art at the Mercy of Light was the title of a 2013 exhibition of Bornstein’s recent work, curated by Oliver A.I. Botar, and held at the former Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon. The exhibition was installed in the gallery’s skylighted spaces, the reliefs subject to the play of natural light with all its variation from dawn to dusk, an ambience seldom, if ever, achieved by more common windowless gallery and museum spaces with their rigid track lighting systems.

Bornstein’s work is indeed at the mercy of light, among other factors, and he has given much thought to and written extensively on lighting his work. He has designed his own house and studio with skylights above his hanging walls in order to allow the most responsive viewing conditions, changeable with time and weather. As he describes in a journal entry, the goal of sensitive lighting is to make the work itself exist in its truest character, to display its colour in its fullest and richest reality. It’s the holy grail, of which the artist is appropriately protective. It is when the reliefs enter the public world, especially for exhibition, that their “precarious existence” becomes most vulnerable, when they pose special challenges to gallerists and museum curators.

Structurist reliefs, such as Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 9, 2000–2001, are not easy to display. The work perishes or is incapable of revealing its subtlety and richness without sufficient light falling down upon it from above. Nor can the desired effect of the work survive harsh, frontal lighting; directional spotlights; or floodlights that, as Bornstein writes, “dissolve the work’s true and gentle character or complicate and confuse its structural relationships with multiple contradictory shadows.” Insufficient light, on the other hand, while not as devastating as too much illumination, also prevents colour from revealing its full intensity, its true hue and value.

Space also offers challenges. An installation must allow sufficient distance so that the viewer can see the work both en face and move about it. “Frontal, side and oblique views are intrinsic” to its viewing and “often the difference between the front and side views is as dramatic as Nature’s plant and animal forms.” Indeed, the entire physical context in which the work is presented can either compromise or fulfill the conditions essential to its optimum realization. The Structurist Relief, to conclude with Bornstein’s own words, is “a fragile medium, like a rare blossom, flower, butterfly, easily destroyed or mishandled, easily vulnerable to abuse.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements