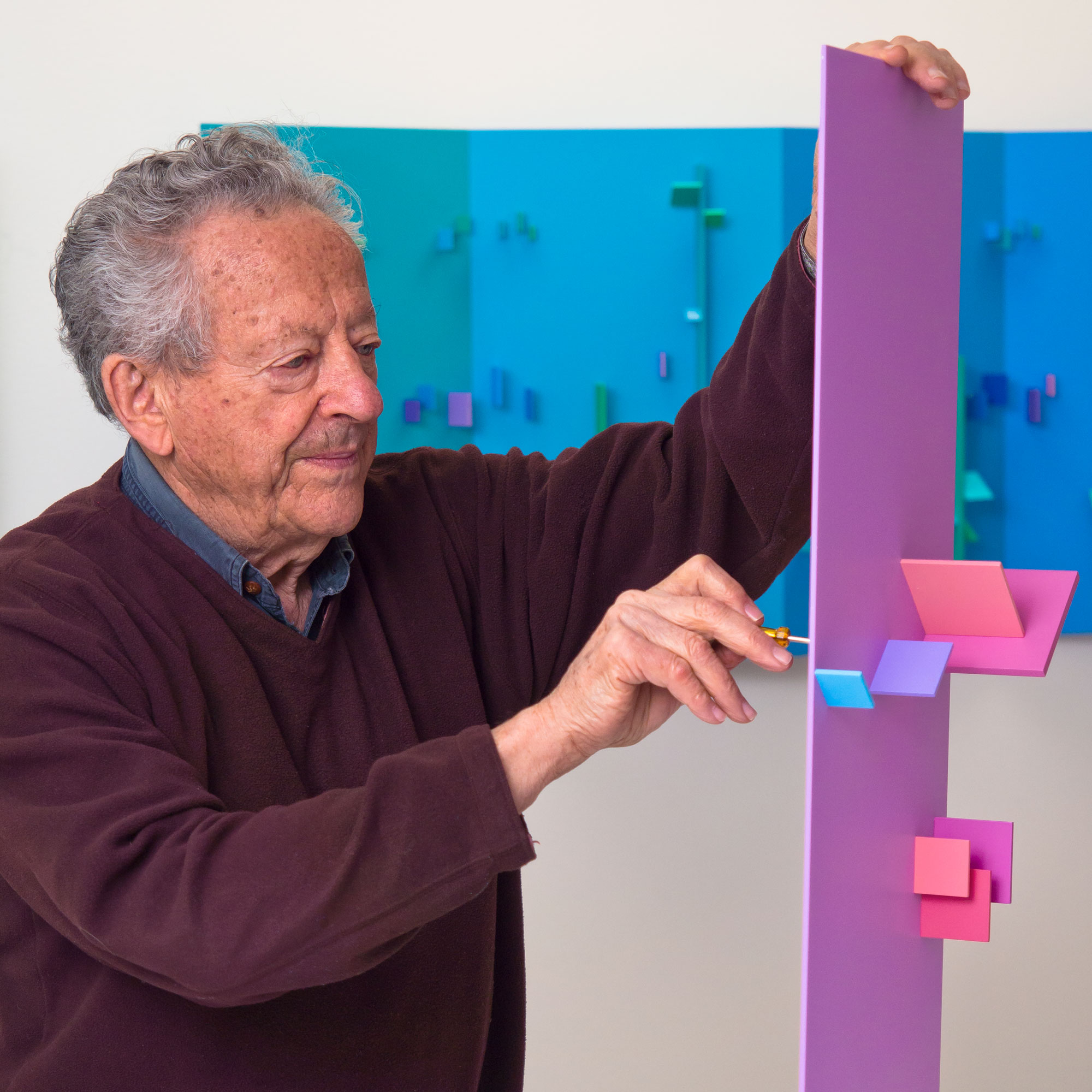

Eli Bornstein’s Structurist art responds to an esteemed modernist tradition that stretches from French Impressionism to the radical abstract work of Dutch De Stijl. As a devoted descendant of the American Transcendentalists, Bornstein dedicates his work to the vitality of the natural world, reinventing and re-evoking it through bold explorations of colour and geometric configuration. Bornstein was also a prolific writer and the editor of the internationally circulating periodical The Structurist, which he published out of the University of Saskatchewan from 1960 to 2020. Breaking new ground with the creation of his dynamic abstract reliefs, Bornstein ultimately defines his artistic self as a “builder,” shedding new light on the wonders of nature in three-dimensional form.

From Representation to Abstraction

Eli Bornstein has, since the 1950s, been an exceptional contributor to abstract art in Canada. He calls his work “Structurist,” a term that, per the dictionary, simply means “builder.” From the start he has disallowed the label “Structurism,” because, as he insists, such terminology would limit the work to a particular school or style, like Cubism or Minimalism.

As a young artist, Bornstein likely did not know that he was heading for abstraction. Yet from early on he developed an acute sense of his place within the unfolding history of modernist art from the Impressionists and onward. When in the mid-1950s he adopted the Structurist model, there was nothing gratuitous about it because he had already worked himself up to it, advancing step by step to the same stage of artistic evolution.

He would have gleaned his knowledge first from his museum visits in Milwaukee and Chicago, but more specifically he learned to hone his conception of art as an evolutionary practice from American relief artist Charles Biederman (1906–2004), whose Art as the Evolution of Visual Knowledge (1948) he first read in 1954. In his manifesto-like seminal essay, “Transition toward the New Art,” and in subsequent writings, Bornstein would argue that a knowledge of history was crucial. “How else is the artist able to secure identity and meaning in his activity but through consciousness of his origins and the accomplishments of his ancestors?” How else, to paraphrase Bornstein, can one advance and grow, except by building on one’s predecessors’ explorations and achievements?

For Bornstein, who, from his earliest realist paintings of the 1940s was enthralled by the play of light, the real start was with Impressionism: its evocation of light, its broken brush strokes, its dots and dabs of colour. Boats at Concarneau, 1952, illustrates how he went on to learn from the Post-Impressionists, especially Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), to impose a more formal structure on Impressionism. By 1953 and 1954, he was wholeheartedly exploring the possible applications of Analytic Cubism, with the fractured cityscapes of the German American painter Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) quite specifically standing behind his own splintered city views of Paris and Saskatoon.

Bornstein’s sculpture simultaneously followed a comparable route from carving in-the-round to the open Cubist construction of his Aluminum Construction (Tree of Knowledge). It, and the watercolour painting The Island, both from 1956, stand as the culminating works of Bornstein’s representational phase. By 1957, like Jack Bush (1909–1977) in Toronto and Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) in Winnipeg, he had come to share the opinion prevailing in advanced art circles of the time: that representational art no longer offered interesting options, and so, with no turning back, he adopted the abstract relief.

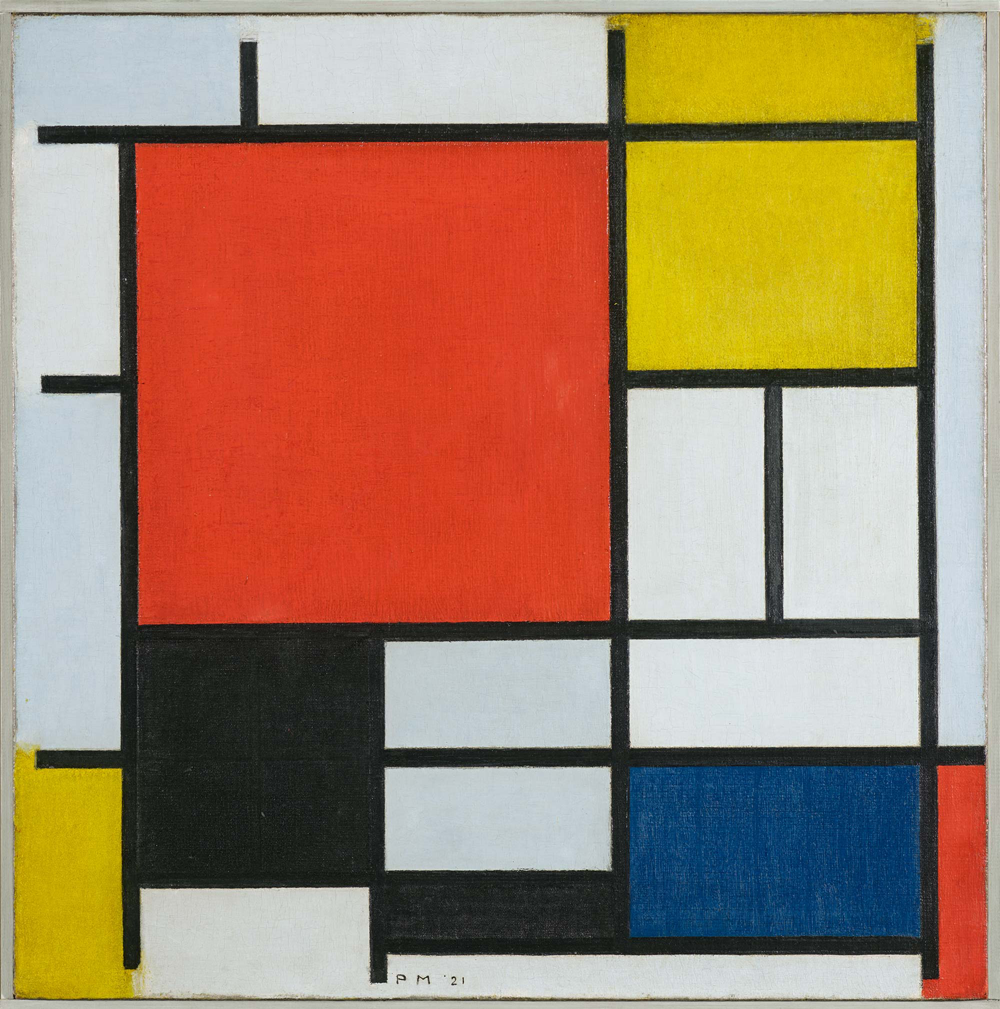

The catalyst for Bornstein was the work of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), who was perhaps the most significant of the artists that he studied during his 1956 to 1957 sabbatical travels in Europe. In his 1958 article, “Transition toward the New Art,” in Structure (the “New Art” soon to be dubbed the Structurist Relief), Bornstein reproduces Mondrian’s Composition with Color Planes 2, 1917, juxtaposing it with one of his own first reliefs, as if to underscore the artist’s impact at that very moment when he abandoned representation for abstraction. The year 1917 had also been a transitional one for Mondrian, who within the next year or so took the decisive step to suppress any residual naturalism, soon to lock his primary-colour planes into taut, flat, rectilinear grids. (See, for example, his Composition with Large Red Plane, Yellow, Black, Gray and Blue, 1921.) His intent was to distill his formal vocabulary into an abstract language that, as simply and purely as possible, could inscribe his quest for “absolute ideal beauty,” a concept that would utterly expel from his painting all that capricious weather of nature that Bornstein for his last time represents in the shimmering mists of The Island.

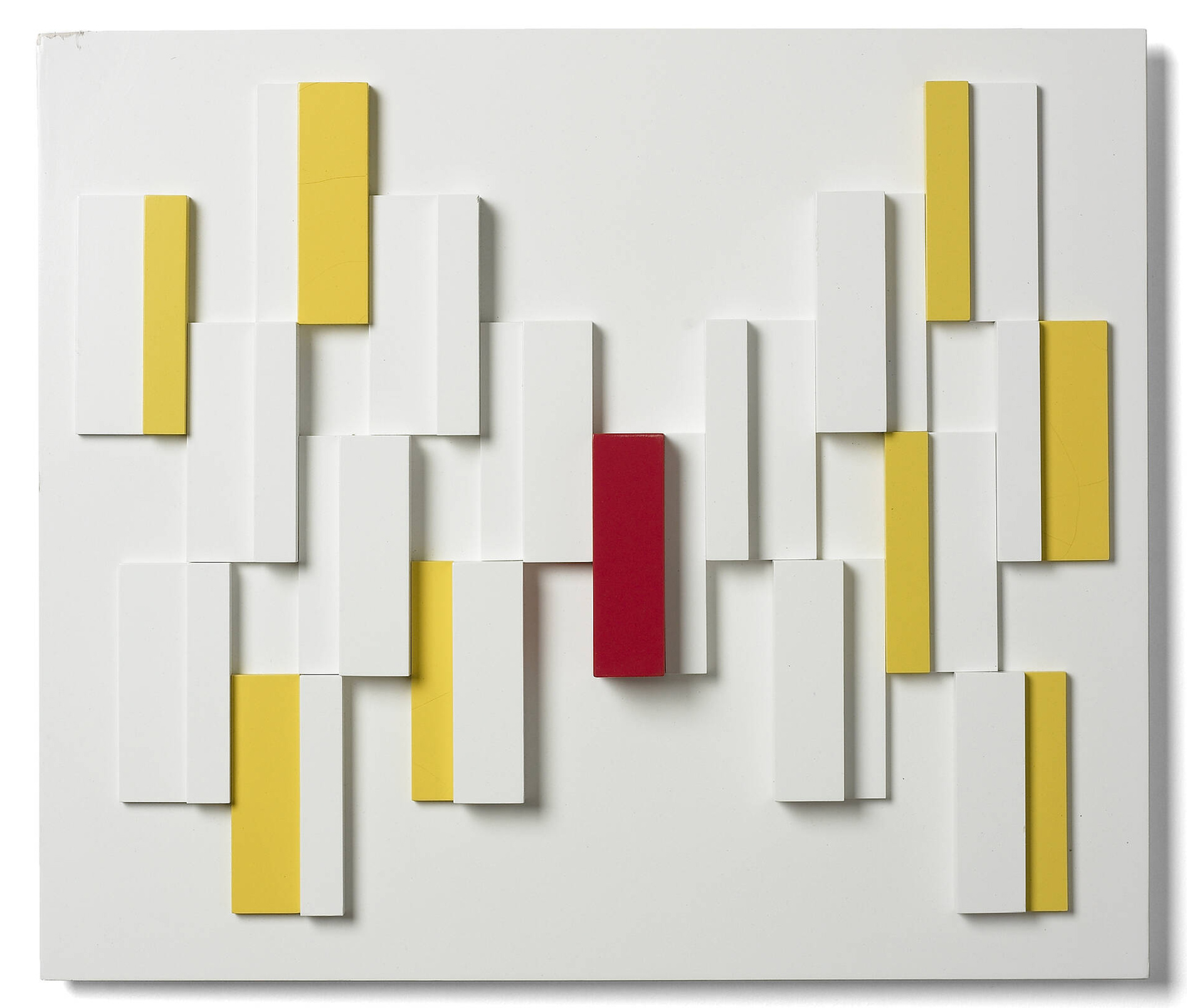

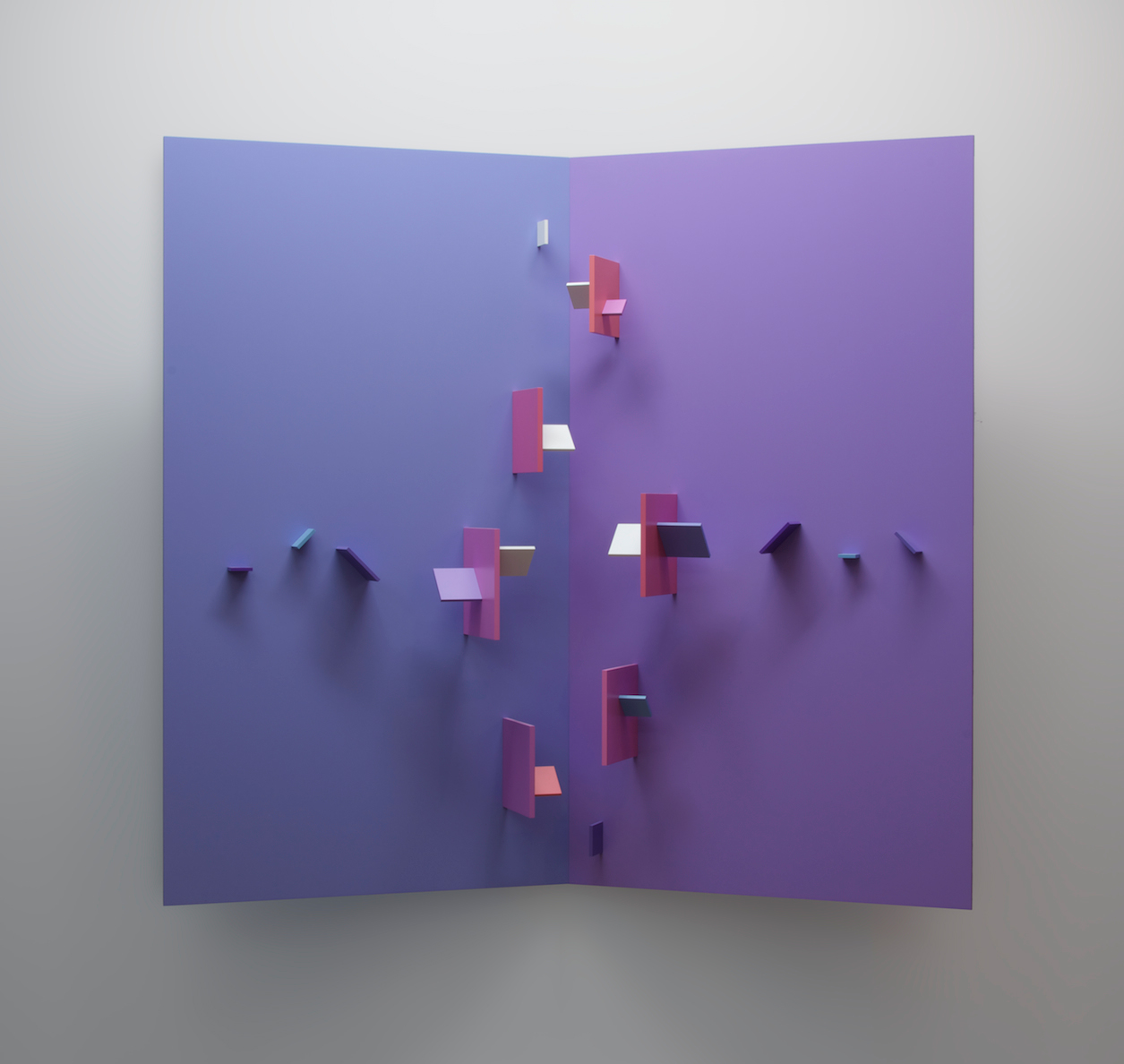

Bornstein was ready to follow Mondrian, shedding representational devices and adopting his rectilinear compositions and use of primary colours, such as in Structurist Relief No. 1 from 1966. But he could not endorse the Dutch modernist’s retreat from everyday reality. Maybe advanced painting could no longer “imitate” nature, but, to Bornstein’s mind, its path went astray when Mondrian decided to turn his back on the real world. But how to honour the co-founder of De Stijl’s formidable formal contributions to abstract art without abandoning the belief that art must encompass the life of nature? How to reject representational painting and still keep nature as your subject matter? Bornstein’s solution would be the Structurist Relief. Working within its rules, he could, on the one hand, stay faithful to Mondrian’s advanced abstraction. On the other hand, the relief provided him a way to re-purpose Mondrian’s vocabulary, releasing it from painting’s flat planes and redeploying it in terms of solid three-dimensional colour structures subject to the laws of gravity, light, and time.

Toward Nature

From the start, for Bornstein, it was a given that the Structurist Relief, even if abstract, was to be based in nature. But it could not imitate nature. Bornstein’s strategy was not to copy, but to reinvent, using colour blocks of various shapes and hues to build visual metaphors for nature’s own colours and events. Bornstein builds his reliefs from the ground up, so to speak, or, rather, from the wall out. The reliefs coexist with us in real space. They are experienced as much viscerally as visually. In plain-speak, we might say that we interact with Structurist reliefs just as we do with other objects, like tables and chairs, except that the function of furniture is practical, and that of the Structurist Relief is aesthetic. And as nature is mutable, the reliefs are never fixed objects. They shift appearance when we change viewpoint, and in response to the light that hits them and the shadows they cast.

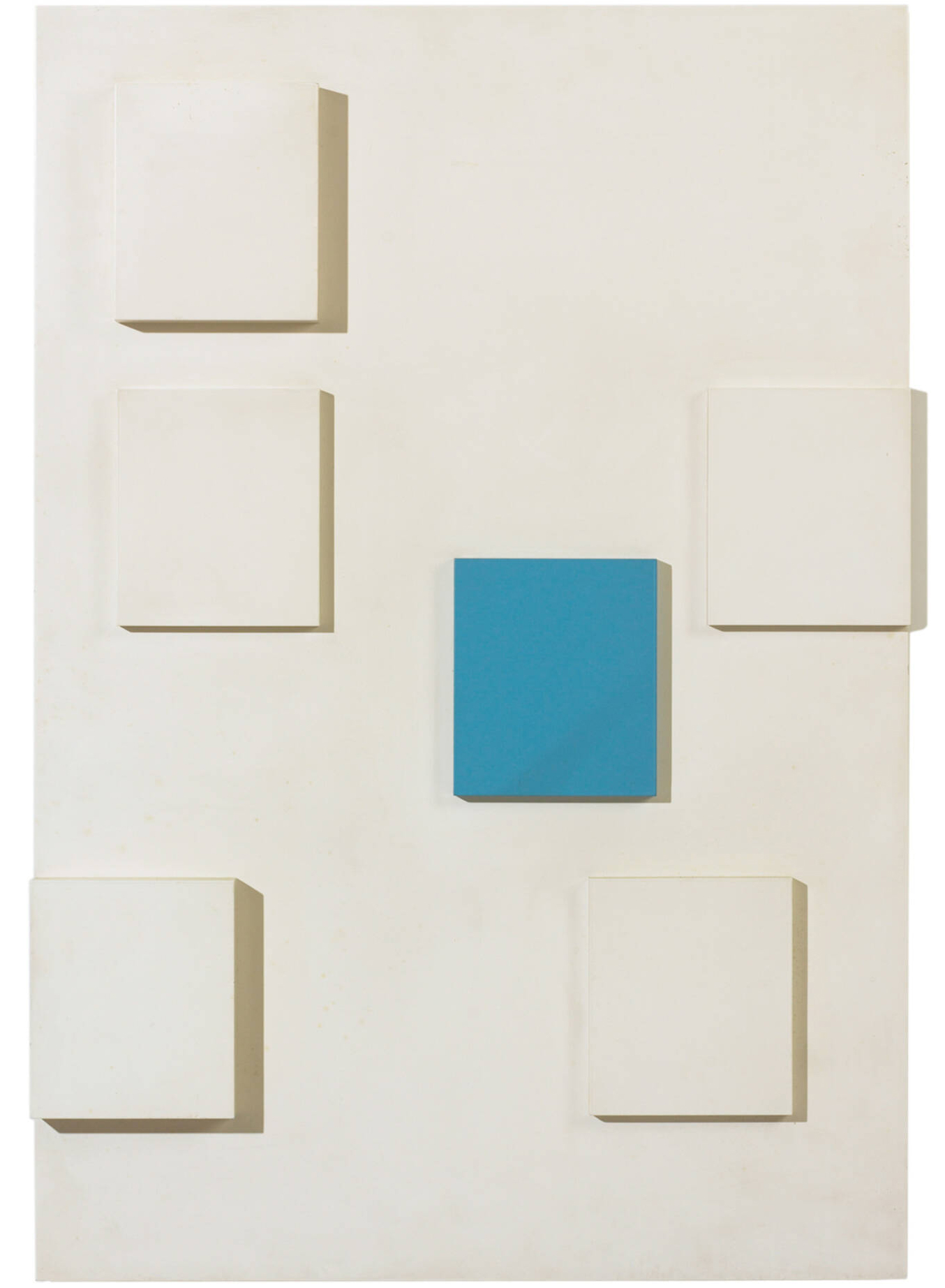

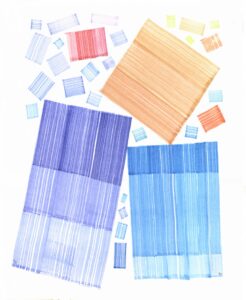

In the beginning, in the mid-1950s, Bornstein’s reliefs were colour-shy—whites and one or two primaries, like in Structurist Relief No. 14, 1957. He had to learn his way. But already they insist on engaging us in real-world existence. Structurist Relief No. 4, 1957, shows us how this works. We see, first of all, the up-front compositional interplay among the six planes of slightly different sizes and thicknesses, five white ones and a blue one. Then we notice how the work has been sharply lit from the left, causing its planes to play a capricious little game of cast shadows.

These are variously weighty or slight so that the planes seem to hover differently. On the far right, one of the planes has been pushed so precipitously to the very edge of the ground, that it, along with its shadow, quite literally wants to escape into the outside world. But this is only one viewpoint, one position. Change the angle of light—or the time of day if the relief is naturally lit—and a new visual game begins. The world is in constant flux.

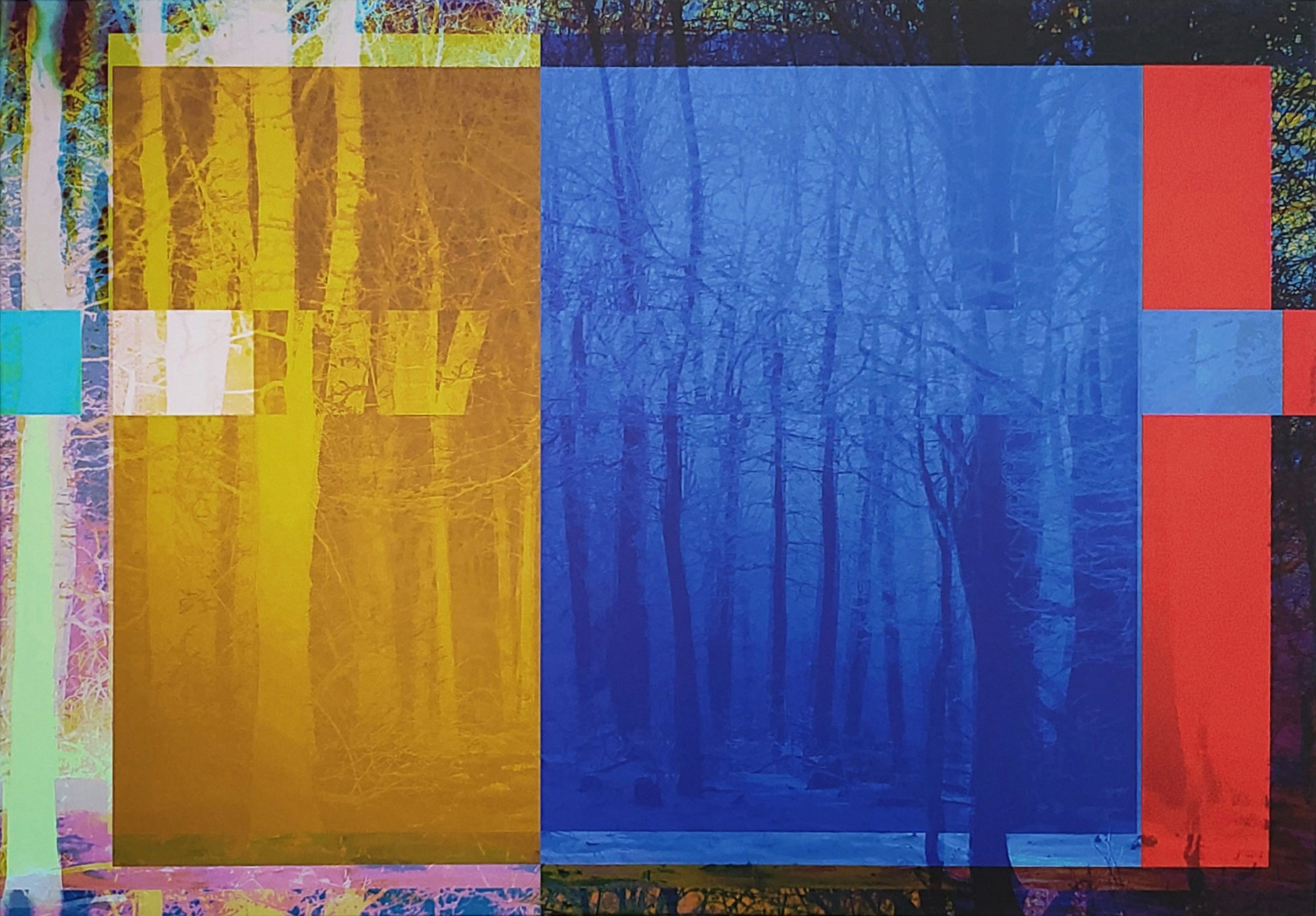

Then, as Bornstein’s observations of the natural world become more intimate, he learns to embrace the colours of the landscapes in front of him. Structurist Relief No. 3-1, 1964, dates to a summer stay in Algonquin Park. Imagine him tromping through the woods or sitting lakeside, in his mind’s eye inventorying the colours of sky and water, the pine needles and birch leaves, the undergrowth of fern fronds and mosses, flowers, and, perhaps, his stumbling on some prematurely dying growth already turning orange.

He would single out all these chromatic experiences individually, and focus them and transform them into what he called his “colour molecules” —the blocks and strips and planes of colour that are the notes that make up his final relief composition. Structurist reliefs then, although immersive in nature, are not its mirrors. Instead, they are new objects interjected into the viewer’s perceptive field within whose compass nature’s processes—here in the northerly forests of Ontario—are re-enacted.

This metamorphosis, the Structurist building process that brings this about, Bornstein has described metaphorically as “organic.” “Through the ‘organic’ development of color in space and light,” he argues, “the otherwise mechanical, technological aspect of the constructed relief can be transcended,” and transformed, “into the warmth of human expression.”

Embracing the Transcendental

Formally, Bornstein’s Structurist work evolves out of early twentieth-century European modernism. In subject matter, however, his dedication to the restorative powers of the undisturbed natural world is more immediately North American, rooted in Transcendentalism, a nineteenth-century intellectual movement based in New England that held that all creation is unified, humanity is essentially good, and that intuition trumps reason.

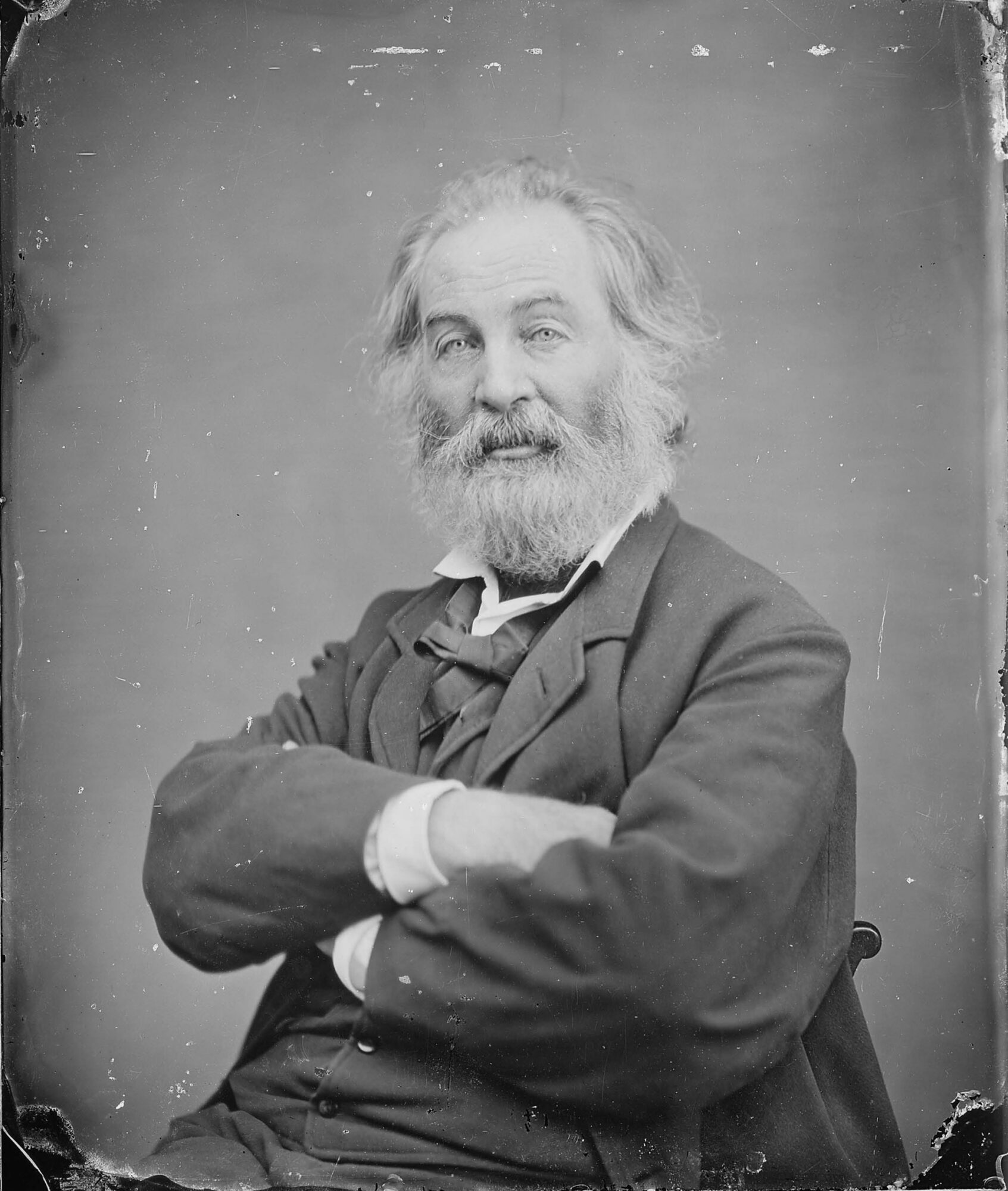

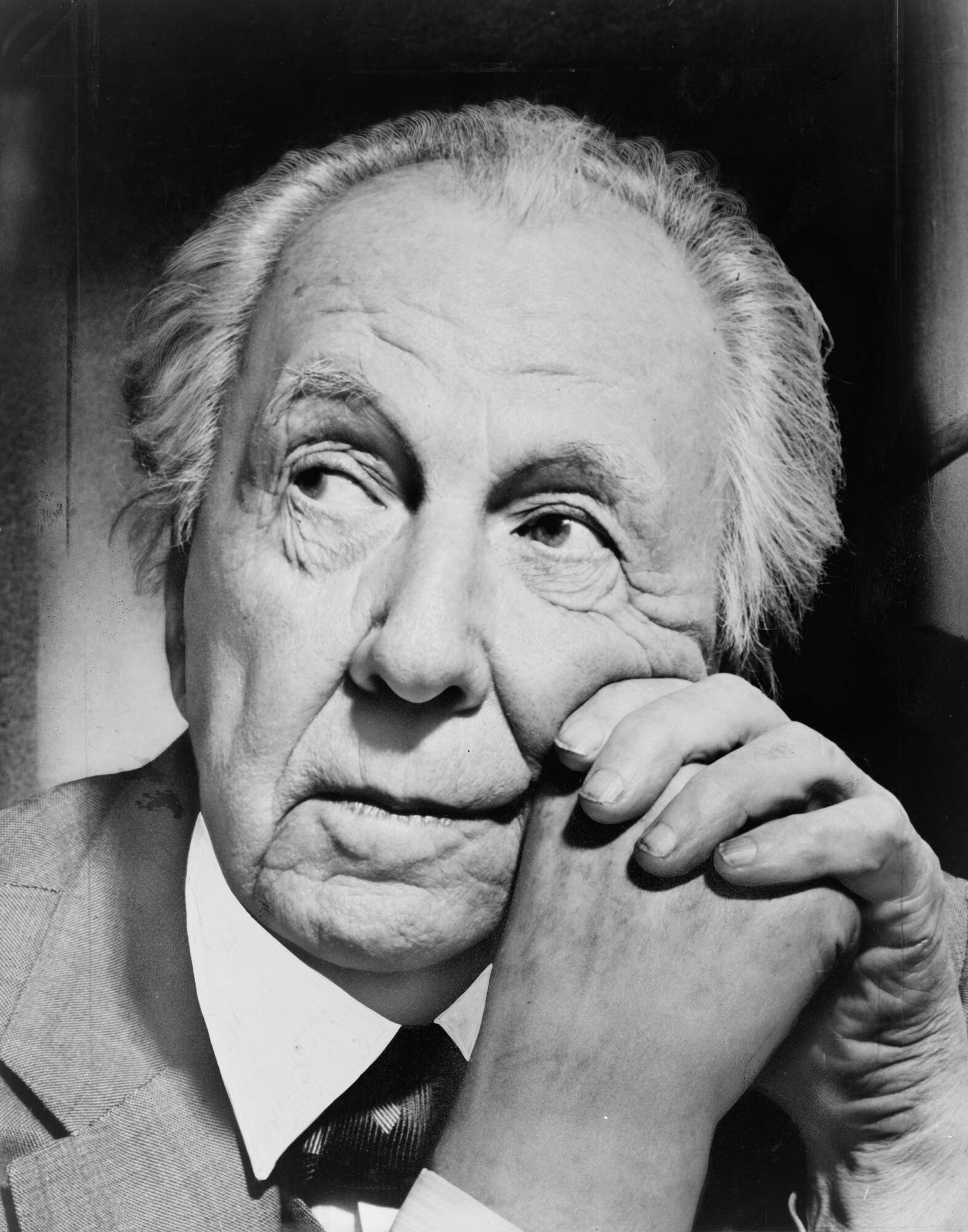

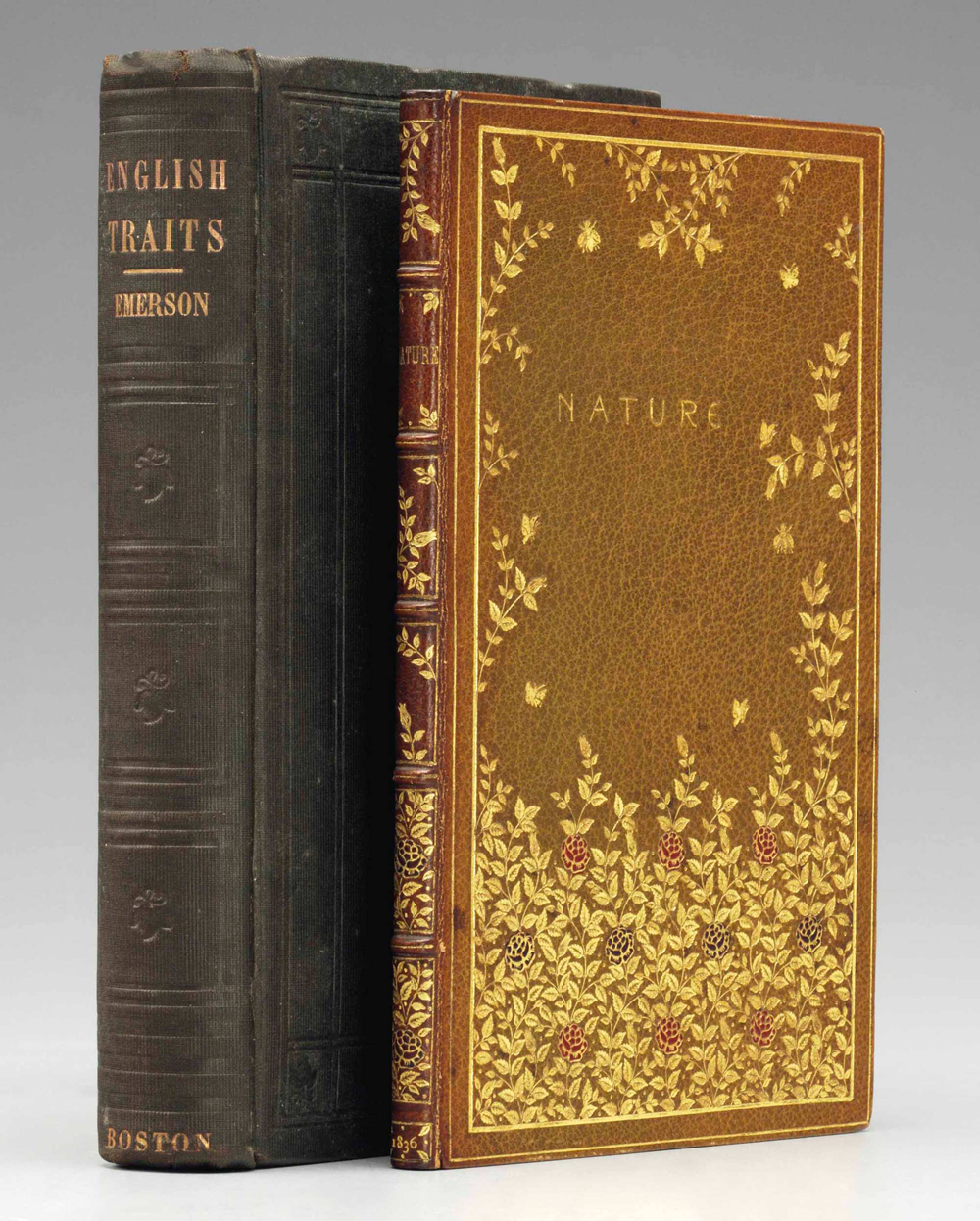

The Structurist Relief is imbued with “the American Grain,” as Bornstein expressed it in a journal entry entitled “Emersonian Continuities.” “There is a vital thread,” he notes, that connects the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), and Walt Whitman (1819–1892), among others, along with the architecture of Louis Sullivan (1856–1924) and Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), to the North American Structurist Relief. For Bornstein, the Transcendentalists are our “literary, philosophical, geographical, environmental” legacy. While the work of European modernists such as Piet Mondrian motivated Bornstein’s embrace of nonrepresentational art, the North American Transcendentalists spurred on his devotion to nature and his deep involvement with colour.

Bornstein called the Transcendentalists at heart “realists” because of how they related directly to nature. And so too is the Structurist Relief “realist,” as both Bornstein and Charles Biederman had argued in their articles in the 1958 issue of Structure. Direct observation and unmediated experience, they insisted, were essential if an artist intended to realize the “palpableness of creative nature.” A Structurist’s work, then, is an objective, even a scientific pursuit. It must, therefore, never be considered an “expressionist” art, lacking any emphasis on internal psychology. Art is not, Bornstein writes, about individual subjectivity or personal feelings, because “art and nature are something greater than the individual person,” greater than a person’s “own ego and unconscious self.” Bornstein considered expressionism in all its forms narcissistic, “a flight from reality” that can only lead to “confusion and lack of direction.”

The Structurist artist, instead, looks at the world with Emerson’s much celebrated “transparent eye-ball,” which banishes all egotism and understands no distinction between the self and the Universal Being. Emerson did not accept any essential distinction between subjective and objective experience, instead maintaining that ideal and transcendental truth coincides with the stuff of reality and flows with it directly and inseparably. Whitman, too, held that “the greatest poet has less a marked style and is more the channel of thoughts and things without increase or diminution…. What I tell I tell for precisely what it is.” Whatever an artist individually may desire to represent and express, wrote the Transcendentalist-influenced Marsden Hartley (1877–1943), is itself “of no importance.”

In a 2009 article, Bornstein summarized the distinction between expressionist-based art and the holistic purview of his Structurist art:

Some art may be viewed as reflecting our own image, internal nature, aspects of our human preoccupations, conflicts, and creativity. Other cultures and kinds of art have been more focused and interconnected to larger natural and cosmic processes of which humans are only a minute and transient part. The first view is anthropocentric, while the other is more ecocentric.

Bornstein’s Structurist art has been wholly devoted to the ecocentric position, evoking the flux of the natural world through our perception of the dynamic behaviour of his three-dimensional reliefs in light and space.

Art as an Act of Worship

Many Canadian landscape artists were influenced by the idea of nature as spiritual, either through Transcendentalism or other “spiritualist” approaches to the landscape. The consummate Canadian landscape artists Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970) and Emily Carr (1871–1945), both devotees of Transcendentalist literature, thought in comparable terms. For instance, in the 1920s and 1930s, Harris spoke from theosophical heights of nature’s sublimities, and Carr used a language that was intimately Christian. A problem for Bornstein, a committed secularist, was just how to give expression to his own wonderment, so comparable to theirs: “It is the failure of written or spoken language,” as he noted in a journal entry, “to find adequate words to describe the experience. ‘Spiritual,’ ‘emotional,’ ‘aesthetic,’ ‘supreme sensory response’ as well as ‘religious’ fail to capture or describe such experience fully or to our complete satisfaction.” Nevertheless, as he had already concluded, writing in The Structurist in 1970:

The creation of art in its deepest sense is like an act of worship, like a prayer. As such it is a communion with Nature and with other human beings. It is at its best an act of belief in life. Transcending the ego, art expands beyond itself towards values and meanings greater than the self…. Here art is essentially a religious act, in the fullest sense of the word “religious.”

The passage is almost mystical and draws Bornstein’s abstract relief landscapes—especially the later horizontal Multiplanes—both spiritually and formally into the tradition that I have elsewhere called Northern Symbolist Landscape Painting.

One can argue that he is an unwitting descendant of that lineage, which includes Northern Europeans like Harald Sohlberg (1869–1935), Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918), and the pre-abstract Piet Mondrian, along with North Americans like Marsden Hartley and Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Harris, and Carr. This was painting also born out of French Impressionism but, by the end of the nineteenth century, bred from a renewed confrontation with the artists’ own northern wildernesses. Driven by their respective senses of a burgeoning spiritual unease, they sought to look beyond surface appearances and to discover something of nature’s inner spirit. “The eternal life is sensed everywhere in the action of nature,” wrote the Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931), as he and his Nordic landscape colleagues abandoned realistic representation to devise new pictorial structures that would resonate, as it were, with the life of the soul. Except for Mondrian, there was little occasion for Bornstein to know these artists, but their paintings shared compositional tropes that he would intuit out of analogous convictions, deconstruct, and then rethink in accordance with his personal artistic impulses and on his own three-dimensional Structurist terms.

Their creators may not be relief artists, but from among the works of Bornstein’s immediate contemporaries, equally dedicated to the landscape sublime, we might add the transformed Northern Manitoba helicopter views of Gershon Iskowitz (1919–1988), where landscape is present only by allusion; the Rococo-sublime skyscapes of Charles Gagnon (1934–2003); the late-career West Coast “entanglements” of Gordon Smith (1919–2020); or, most recently, the digitally generated large-scale sublime landscape images of Christian Eckart (b.1959).

Ecological and Environmental Concerns

Even as Bornstein celebrates the natural world, he nevertheless shares with early twentieth-century abstract movements a progressive, even utopian vision that art can be practically applied to contemporary life and to the improvement of the common good. As he writes in a journal entry:

Just as green spaces of wild vegetation, like trees and grass (as well as free expanses of sky and water) are necessary to human health, perhaps even a genetic requirement to our survival in our technological man-made cityscapes, so art, like music, can or should provide the kind of inspiration, tranquility, sense of belonging in our increasingly hostile or inhuman environments. How to live a sane, peaceful, and relatively simple life in our increasingly complex world is a primary question confronting the twenty-first century.

This, for all intents and purposes, is the mission statement of The Structurist, the internationally circulating periodical that Bornstein founded in 1960 and produced regularly until 2010 (with an anniversary issue in 2020). Art historian Oliver A.I. Botar has called this publishing venture one of Bornstein’s “most important achievements within the landscape of Canadian art and intellectual history.” Botar has also highlighted how Bornstein’s periodical declared his ecological thinking and environmentalism “years before the rise of politically engaged art beginning in the late 1960s, and well before any other Canadian artistic periodical.”

-

Eli Bornstein with the cover proof of the 1997–98 issue of The Structurist, 1998

Photographer unknown, University of Saskatchewan, University Archives and Special Collections

-

Cover of The Structurist, no. 11, “An Organic Art,” edited by Eli Bornstein (Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan, 1971)

-

Cover of The Structurist, no. 49/50, “Toward an Earth-Centred Greening of Art and Architecture,” edited by Eli Bornstein (Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan, 2009–10)

-

Cover of The Structurist, no. 2, “Art in Architecture,” edited by Eli Bornstein (Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan, 1962)

Over the years, the contributors to The Structurist have included a host of artists, architects, and intellectual luminaries from around the world: Josef Albers (1888–1976), Naum Gabo (1890–1977), Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), Erwin Panofsky (1892–1968), Murray Adaskin (1906–2002), Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980), George Woodcock (1912–1995), Elizabeth Willmott (b.1928), Zaha Hadid (1950–2016), and Arne Næss (1912–2009). More recently, the journal has featured a long list of younger international contributors, as well as writings by Bornstein himself, with essays or interviews in every issue. The periodical has explored art and its relations to science, technology, music, architecture, literature, philosophy, religion, and environmentalism, with many of its articles not directly associated with Structurist art.

As Bornstein has explained, it was in the spirit of free inquiry that he solicited articles that were “meaningful and provocative challenges” to his own artistic position: “It seems increasingly apparent that real nourishment for art is not to be found in art writing” alone. Rather, he believed, the real problems in art relate to the problems of society and to humanity itself. The cover of the 1971 issue of The Structurist, which was adorned with an iconic NASA view of the Earth from space, “was devoted in its entirety to the relationship between humanity and nature in relation to artistic production, surely the first eco-artistic publication in Canada, and one of the first anywhere.” Later, Bornstein declared his critical sympathy with both Earth First! (1980–), perhaps the most radical of the environmental activist groups, and Adbusters (1989–), the Vancouver-based anti-consumerist and environmentalist journal. The 2009–10 issue of The Structurist is subtitled “Toward an Earth-Centred Greening of Art and Architecture.”

What Bornstein wrote in a journal entry from 2012 speaks to his sense of ecological and environmentalist urgency: “The overwhelming dysfunctionality that pervades our global culture calls for the emergence of an ethos with a need and determination for exploring a new sustainable and consilient art and architecture that will lead towards a vital rebirth and to the efflorescence of a new harmony, beauty, and enrichment for our future world.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements