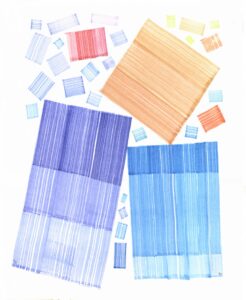

Saskatoon 1954

Eli Bornstein, Saskatoon, 1954

Gouache on gesso panel, 58.5 x 74 cm

Private collection

At the start of his career in art, Bornstein created representational works. This jaunty gouache painting depicts the Bessborough, one of Canada’s grand Château-style railway hotels, which opened in Saskatoon in 1935. Its composition is dynamic, unstable, and even dance-like. It reminds us that a young Bornstein had played percussion in jazz bands. In journal entries, he has recalled how jazz improvisation stimulated his early path into abstraction and was an important factor in how he would come to compose his Structurist reliefs.

Saskatoon may be a composition of tilted geometries and Cubistic fragmentation, but it is no imaginary rendering. It is more or less topologically correct. We are set down in the middle of Twenty-First Street, Saskatoon’s major business thoroughfare, looking toward the hotel with the Canadian National Rail station behind us. In 1954, the Bessborough was still the city’s tallest building. In the centre foreground, at the intersection of Twenty-First Street and Second Avenue, stands the 1929 war memorial cenotaph showing the west side of its four-faced clock (for traffic reasons, the cenotaph was relocated in 1957). The hotel reigns over a nearly symmetrical composition reminiscent of images by the German American artist Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956), especially his Cubist-inspired exultant Gothic church in The Market Church at Halle, 1930. Like Feininger, Bornstein peoples his streetscape with little stick-like figures (and some cars), and he even, in Feininger’s spirit, crowns his edifice with a radiant aureole. But where Feininger’s voice is a touch stentorian—loud, powerful, and authoritative—Bornstein’s is light and scintillating.

When by 1954 Bornstein found his way to Cubism, it was a near inevitable consequence of what had become his step-by-step study of the development of modernist art from Impressionism and forward. His challenge was to master its evolutionary progression, to find his place within it, and eventually to further it. Successively, Bornstein had painted with the broken brush strokes of the Impressionist; had learned from Post-Impressionist master Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) how to give Impressionism form and structure; and had gone on to master the style known as Analytic Cubism, which confounded traditional ways of representing depth, instead fragmenting its subject matter into quasi-abstract shallow webs of interpenetrating planes.

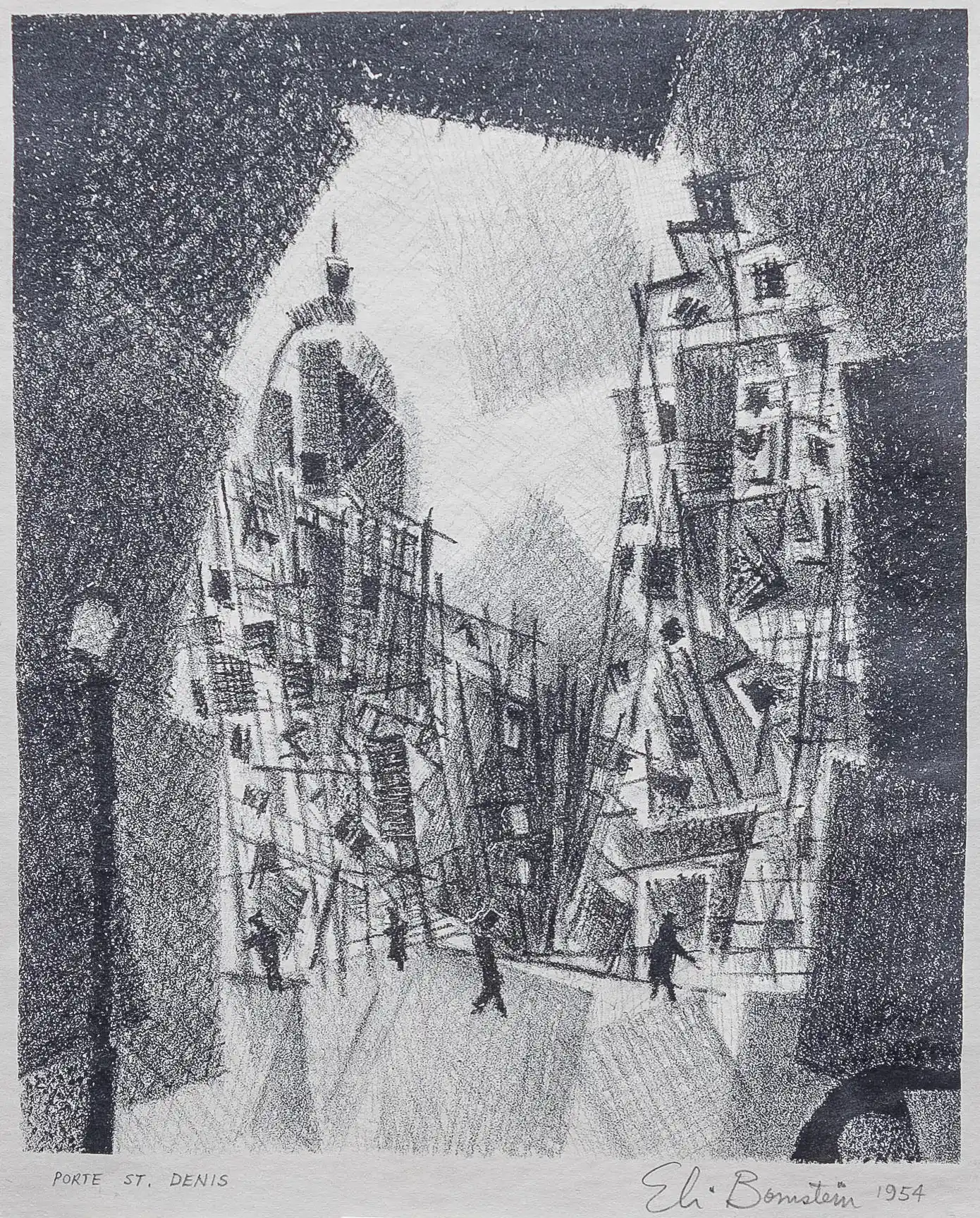

Feininger’s city views also influenced Bornstein’s Parisian drawings, like Porte St. Denis, 1954 (which was also issued as a lithograph). Moreover, the fractured scaffolding on the building’s facade is a premonition of Bornstein’s monumental constructed sculpture Aluminum Construction (Tree of Knowledge), 1956.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements