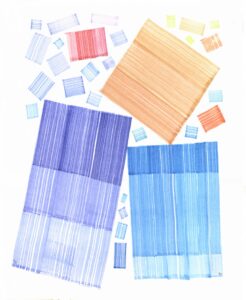

Quadriplane Structurist Relief Nos. 1–3 (River-Screen Series) 1989–96

Eli Bornstein, Quadriplane Structurist Relief Nos. 1–3 (River-Screen Series), 1989–96

Acrylic enamel on aluminum and Plexiglas, 60.4 x 137.8 x 14.6 cm each

Collection of the artist

The above image depicts (left to right) Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 1 (River-Screen Series), Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 2 (River-Screen Series), and Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 3 (River-Screen Series) by Eli Bornstein, photograph by Roald Nasgaard.

In the late 1980s, subsequent to his Arctic experiences, Bornstein began a new series of horizontally oriented Quadriplane and Hexaplane reliefs, which, with their expansiveness and their resonant intonations, stand as one of the culminating achievements of his long and creative career.

-

Eli Bornstein, Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 1 (River-Screen Series), 1989–96

Acrylic enamel on aluminum and Plexiglas, 60.4 x 137.8 x 14.6 cm

Collection of the artist

-

Eli Bornstein, Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 2 (River-Screen Series), 1989–96

Acrylic enamel on aluminum and Plexiglas, 60.4 x 137.8 x 14.6 cm

Collection of the artist

-

Eli Bornstein, Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 3 (River-Screen Series), 1989–96

Acrylic enamel on aluminum and Plexiglas, 60.4 x 137.8 x 14.6 cm

Collection of the artist

In the three-part Quadriplane Structurist Relief Nos. 1–3 (River-Screen Series), a sequence of colour planes, one by one, advance from left to right through daylight greens into blues and late-dusk purples. When we scan the horizon of their panoramic sweep, they zigzag in and out like little jump-cuts in the continuity of time. The foreground articulations are dispersed with rhythmic dash, causing the eye to search out their individual colours and shapes, and explore their positions, angles, and relationships as they catch the light and throw shadows. They flow in space and time like a progression of musical chords interspersed with grace notes and pauses. Behind them, the ground colours unfold their quietude and fulsomeness as if to hint at a larger existence far beyond their outer edges. Before them the transitory life of nature continues to perform its ephemeral dances while the colour planes themselves hold vision in a state of suspension within a space of timelessness.

Bornstein has always been mindful about titles, preferring numbers to descriptive names in order to deter viewers from imposing representational references before exploring structural relations (what descriptions he does use—Quadriplane, Hexaplane, and Double Plane—refer to the number of planes in each relief’s construction). But sometimes subtitles, such as River-Screen Series, anchor us. Let the artist himself describe the natural sources of the series’ formal correlatives:

As I walk out upon the riverbank each day…. My river is like an unfolding ribbon or screen of color that reflects the constantly changing light of the sky and position of the sun. Diurnal and nocturnal, throughout the changing seasons, there is a continuous transition of color from greens to blue-greens, green-blues, to intense blues, purple-blues and deep purples. There are ranges of intensity and value and transitions and mergings of one into another along this horizontal stretch of color. There is not a color of the entire spectrum that is not sometime to be seen here. No artist can invent a color that this strip of chromatic mirror cannot reflect.

The triptych is a tour de force celebration of nature: the glory of an early morning sunrise, the greenness of spring, or the melancholy of the dying day. Scandinavians in the late nineteenth century called the latter “the blue hour,” in whose twilight they could elevate their meditations into almost mystical rapture. And Bornstein’s reliefs are enraptured with “Nature” (as Bornstein often capitalizes it).

Bornstein’s Multiplane reliefs are in a way unwitting descendants of the Northern Symbolist Landscape tradition, born in the 1890s from a renewed confrontation with the northern wilderness during a time of fin de siècle spiritual unease. Dissatisfied with the objective realism of Impressionist paintings, artists—like the Norwegian Harald Sohlberg (1869–1935)—began to probe behind surface appearances and meditate on nature’s inner spirit. “The eternal life is sensed everywhere in the action of nature,” wrote the Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931), as he and his Nordic-landscape colleagues abandoned realistic representation to devise new pictorial structures that would resonate, as it were, with the life of the soul.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements