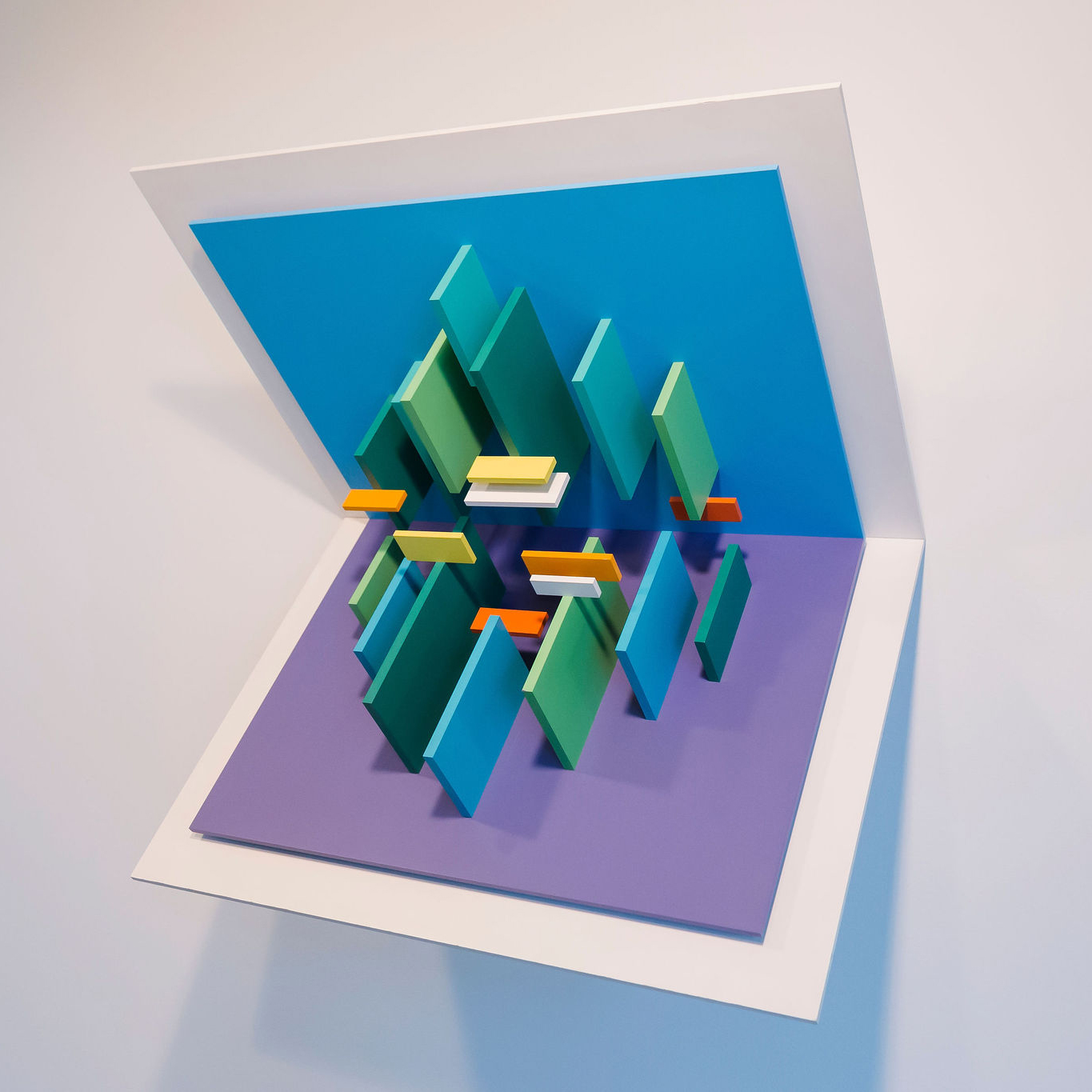

Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 3 1967–69

Eli Bornstein, Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 3, 1967–69

Enamel on Plexiglas and aluminum, 66.7 x 66.7 x 34.3 cm

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon

Bornstein began working on Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 3 in 1966 while on sabbatical near Big Sur, California. As he recounts in a journal entry from 2013, “My vision opened daily to an immense sky above and the Great Pacific Ocean below that could as well have been the great prairie plane of Saskatchewan.” He produced Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 3 in response to this observation and the fact that the visual ways of the natural world are infinitely variable.

In this work, Bornstein folds his ground plane in half, at a 90-degree angle, and then installs it horizontally. It performs like a half-opened book, its spine flat to the wall. Nested in its crevices are brightly coloured, often intricate relief elements, their chromatic interactions animated by the play of light and shadow.

In Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 2-1, 1966–71, Bornstein flipped the axis to the vertical. This was prompted, as he writes in an article from 1969, by watching “the wild orange-red flowers that grew around our house.” As he continues: when the relief’s angled planes unfold, it is as if it “reaches out and draws the spectator into it, like the flower inviting the bee!” Another of Bornstein’s journal entries, “The First Lily,” underscores the intensity of his observations of the natural world outside his door:

Today I was startled by the appearance of the first lily. What a surprise to suddenly see the bright orange trumpet-like flower appear so strikingly, so triumphantly amidst the tall prairie grass and in the most unexpected places on the riverbank. How very different the character and gesture of the lily are from the crocus and the rose. Its form and color are more precisely articulated with its single stem and arrangement of leaves. It appears far more singularly, and in isolation, being far less gregarious than the rose. Like the solo sound of a high-pitched horn, or soprano trumpet resonant and clear, it is unmistakable for anything else but itself.

Despite his deep engagement with the natural world, Bornstein reminds his viewers that when he builds his abstract constructions, they do not mirror or copy nature, preferring to describe them as “parallel creations” that “grow toward nature.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements