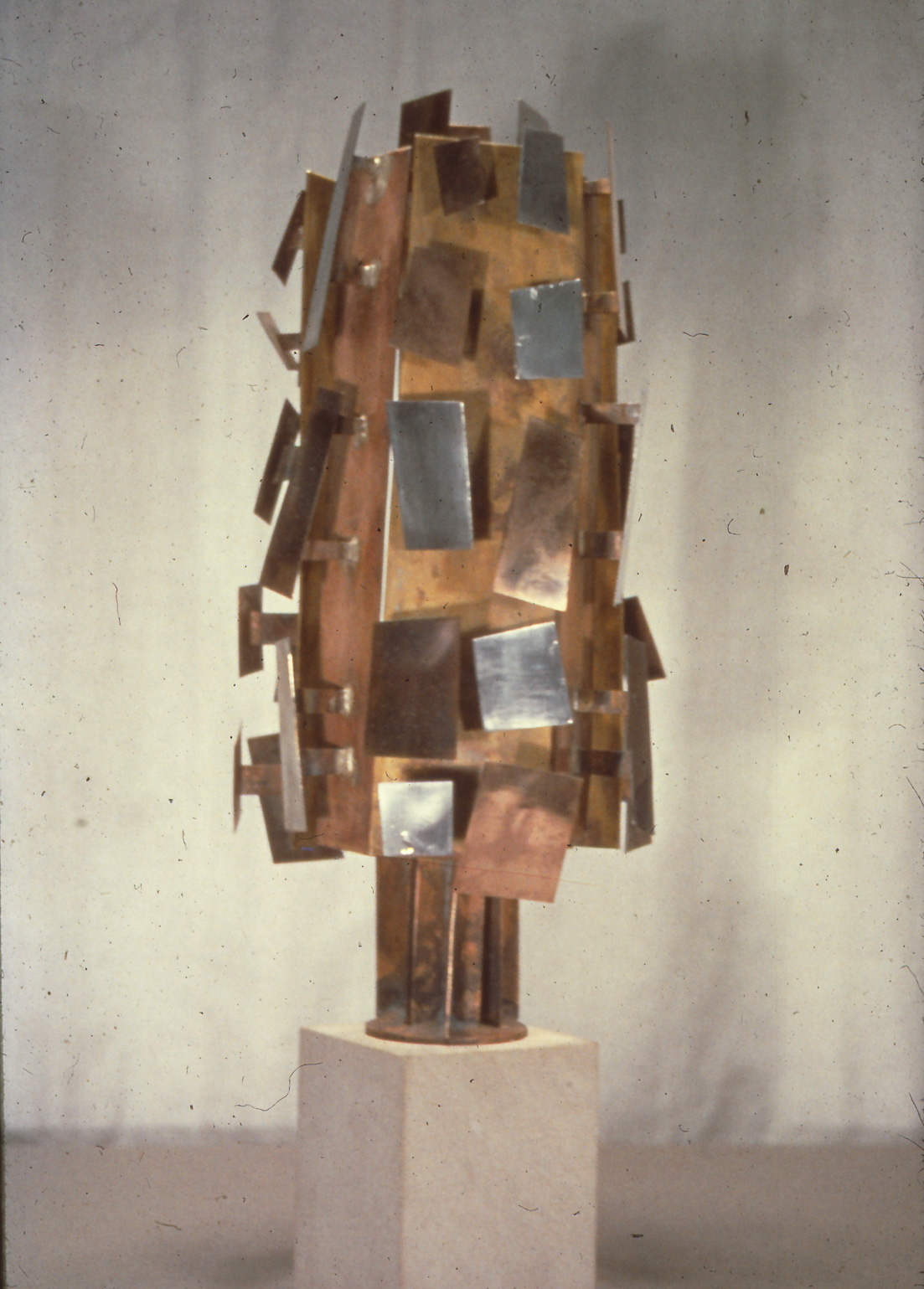

Aluminum Construction (Tree of Knowledge) 1956

Eli Bornstein, Aluminum Construction (Tree of Knowledge), 1956

Welded aluminum on stone base, 458 cm (height)

Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation Building, Saskatoon

In 1956, Aluminum Construction (Tree of Knowledge) was the first abstract public work to be installed in Saskatoon. The initial public responses, as expressed in letters to the daily newspaper, the Star-Phoenix, ranged from anger to outrage and hostility. Perhaps they did not like, want, or understand abstract art. Many called for its removal and demanded that the artist be dismissed by the University of Saskatchewan. Bornstein himself was on sabbatical leave in Europe at the time, but the one person who in his absence came to his defence publicly was the musician and composer Murray Adaskin (1906–2002). As Bornstein recounts, he “as valiantly championed the validity of abstract art as he had championed new music.” In 1963, the American critic Clement Greenberg (1909–1994), touring the prairies for the magazine Canadian Art, despite some reservations, called the “overall conception” of Tree of Knowledge “magnificent,” concluding that “the artist responsible for it stands or falls as a major artist and nothing else.”

Tree of Knowledge was commissioned for the new Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation Building at 902 Spadina Crescent East, designed by Saskatoon architect Tinos Kortes (1926–2014), who had also recommended Bornstein for the project. The sculpture was manufactured in Regina, where the necessary equipment for welding aluminum was available, and then shipped to Saskatoon. In 1969, the work was moved to the new Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation Building at 2317 Arlington Avenue.

As a sculptor, Bornstein had heretofore primarily been a carver of wood and stone, often working with an eye to Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957), and attentive to the Romanian artist’s formal simplifications and his sensitivity to materials. In contrast, Tree of Knowledge, with its intricate internal scaffolding and its out-thrust reflective aluminum plates, shows the influence of Russian Constructivism. Constructivist sculpture, such as Naum Gabo’s Constructed Head No. 2, 1923–34, is assembled or built, usually with non-traditional industrial materials like metal and plastics.

Bornstein began to transition from working with mass to openwork metallic constructing during a stay in New York while he was envisioning how Tree of Knowledge should look. In his earliest models for the sculpture, he pushes light-reflective rectangular metal planes outward into space from a heftier inner core in a configuration suggesting something like pollen grains releasing from a giant flower stamen. The materials are brass and bronze, metals he was familiar with from jewellery-making classes at college. In subsequent models, he dissolved the heavy central core into an airy structure that then evolved into the final monumental 4.58-metre-tall welded aluminum construction.

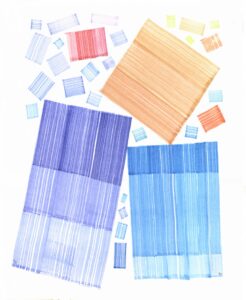

Tree of Knowledge belongs to the tradition of Cubistic abstraction, its configurations derived from the deconstruction of the appearances of the visual world; it is not to be understood as a pure abstract sculpture. Its formal components had already been predicted in drawings from a couple of years before—including Porte St. Denis, 1954—influenced by German American artist Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956). But now the subject matter is the natural rather than the urban world: the free-floating atmospheric rectangles of the contemporary watercolour The Island, 1956, here extrude as shimmering aluminum plates energized by real light. The structural whole is a geometric redesign of the anatomy of a coniferous tree, with its network of branches, tiered and drooping, and its natural growth re-experienced in the rhythmic bustle of light and shadow.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements