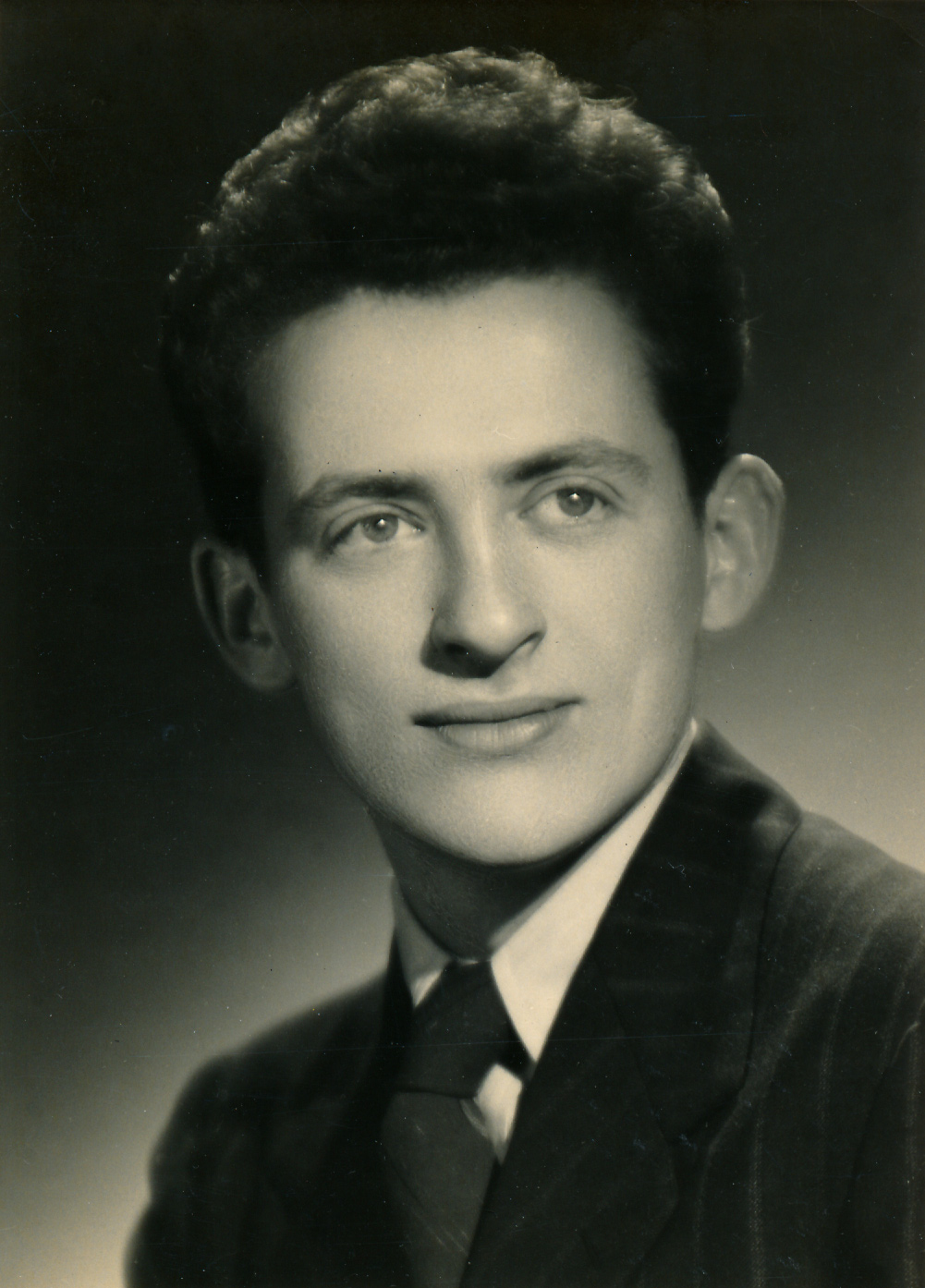

For the past half century, Eli Bornstein (b.1922) has been a unique contributor to abstract art in Canada. Born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he accepted a position at the University of Saskatchewan in 1950, Saskatoon becoming the base for his multi-faceted career. Initially both a painter and a sculptor, he soon combined these two practices into a lifelong commitment to what he would call the Structurist Relief, a three-dimensional art form that is simultaneously rigorously abstract and deeply rooted in the phenomena of the natural world. Both the prairie landscape and the Arctic have been constant inspirations for his creative thinking.

Early Years in Wisconsin

Eli Bornstein, future teacher, writer, and publisher, and ultimately the consummate Structurist artist, was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on December 28, 1922. His parents came from Lithuania. They had arrived separately in the United States in 1904 and eventually met and married in Milwaukee. Bornstein knew little of their life before they immigrated other than that it was full of hardships, overburdened with work and poverty. Neither one, as he writes in a 1997 journal entry, had the privilege of a good education or the comfort of a close family life. And neither parent—both of whom were raised in Orthodox Jewish homes—“found solace in the Synagogue, in religious belief or practice [because] they could never overcome the hypocrisy they experienced from religious people, the bigotry, the fanaticism, intolerance and deceit.” Both his parents wanted to forget what they had left behind when they emigrated, looking ahead, instead, to America’s promise of a better future in a free and democratic society.

The household Bornstein grew up in during the 1920s and 1930s was one that had to watch its pennies, but it was nonetheless a stimulating environment. Because his parents had turned their backs on religion, Bornstein was not educated in Hebrew or Judaism, and he did not have a bar mitzvah. As he recalled to curator Jonneke Fritz-Jobse in her 1996 exhibition catalogue essay, his parents were religious freethinkers, pacifists, and attracted to socialism. Dinner conversations would engage in questions of ethics and philosophy. “We would talk about the existence of God and the meaning of life. We would talk about social and philosophical questions of every kind.”

The family home was filled with music. “My mother often said that ‘here on earth, the closest we can get to God is through art’—meaning all the arts and human creativity and particularly music.” In a journal entry, Bornstein remembers how in the 1930s his older sister Dorothy would practise her piano lessons in the living room, playing Bach. He played the drums in his high school band, and then in dance bands as a way of earning money to pay for his college education. “I was in my late teens in Milwaukee in the late 30s and early 40s when I heard some of the best jazz bands and artists that were there often—Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Gene Krupa, Harry James, Les Brown, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, etc.” Although Bornstein finally quit the dance bands when evening and weekend performance schedules, as well as travelling, interfered too much with his schoolwork, his youthful music experiences were foundational to his art.

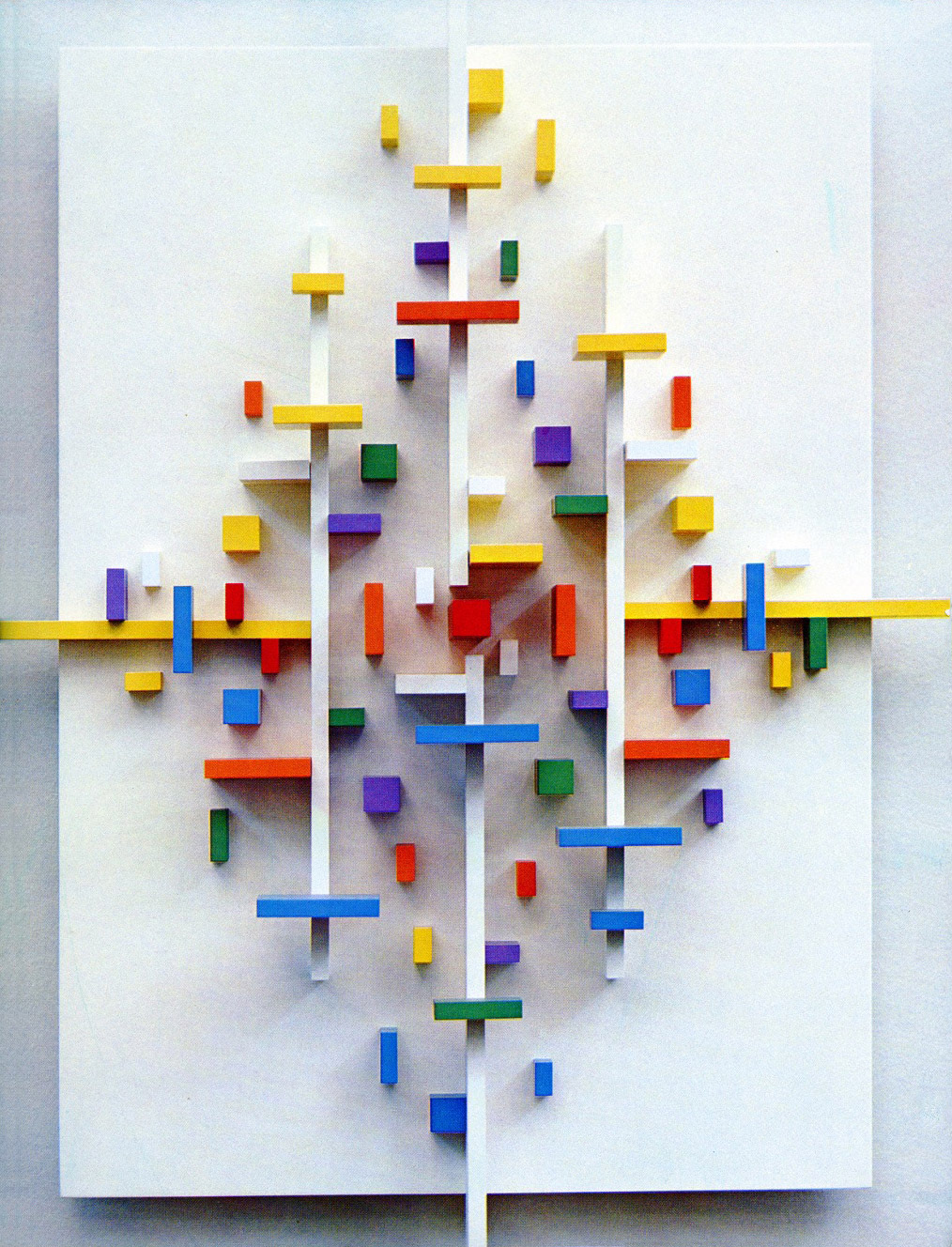

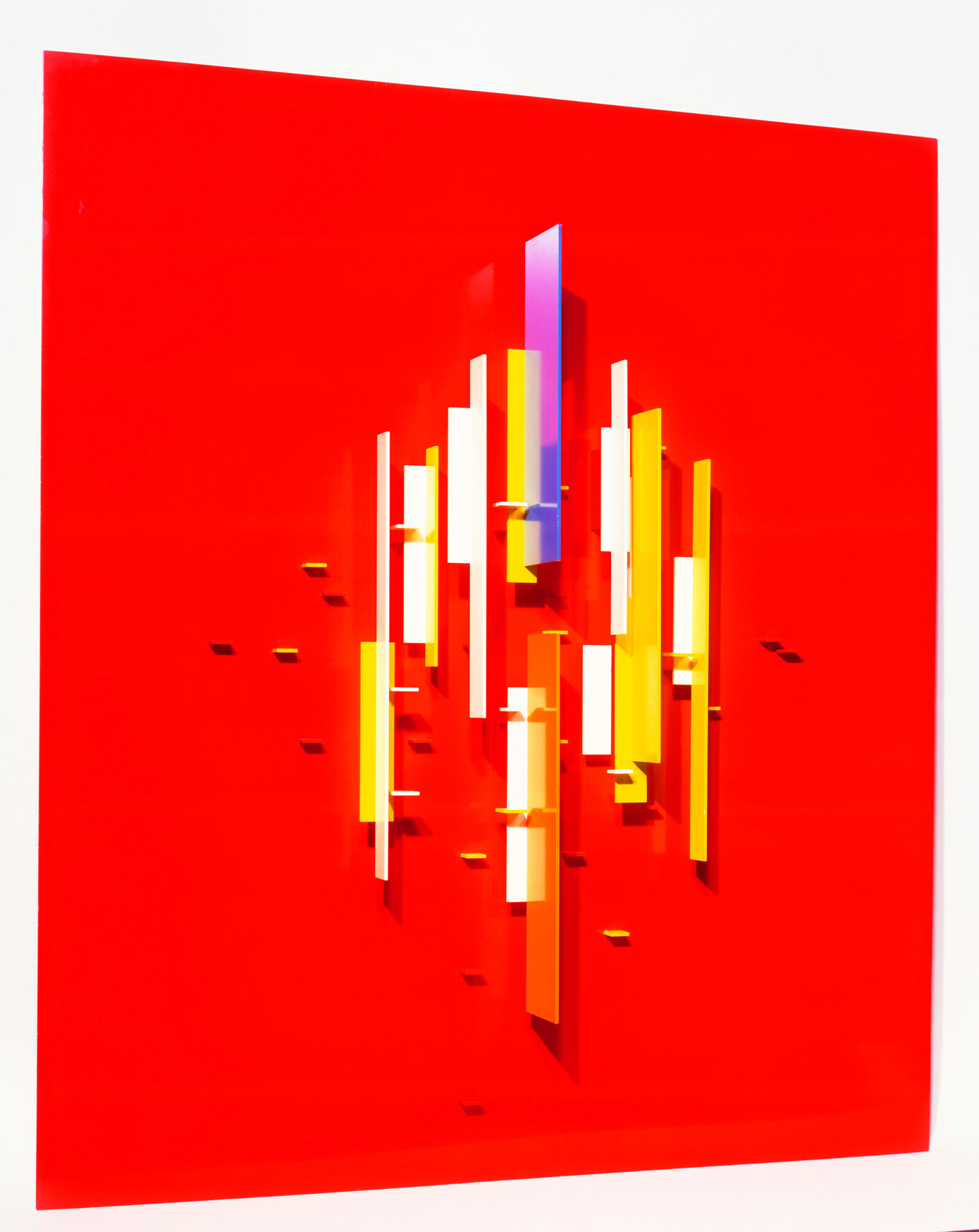

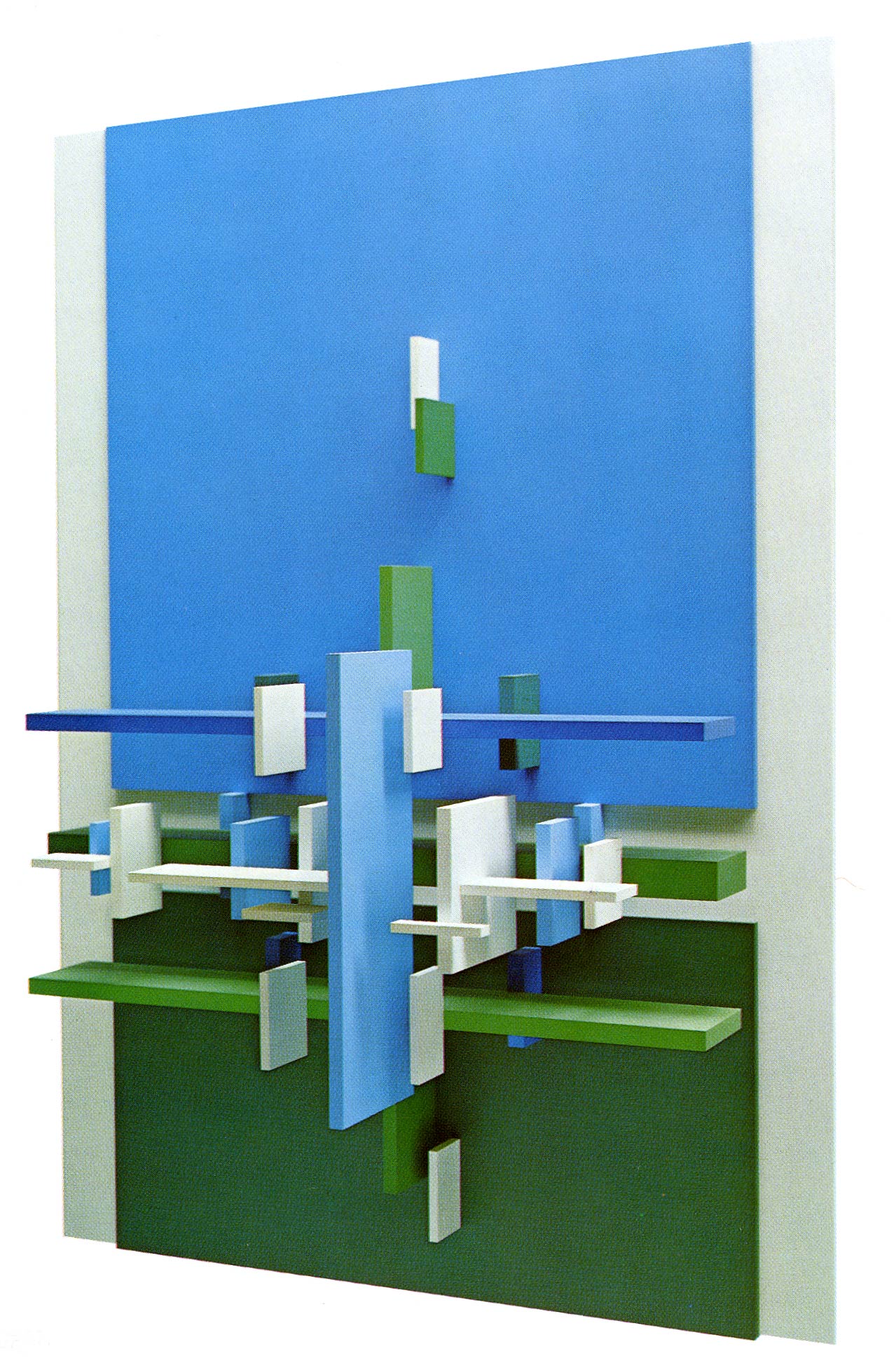

In a 2006 journal entry entitled “Jazz as an early influence toward abstract art,” Bornstein analyzes vividly the analogies between music, especially jazz improvisation, and his future Structurist compositional practice, in works such as Structurist Relief No. 1, 1965. As he writes, “The physicality of jazz as it related to dance and movement … [offered me] an early education of mind, senses, and body toward the animality of abstract visual art.” Jazz music was a common reference point for many modernist artists as they explored abstraction throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.

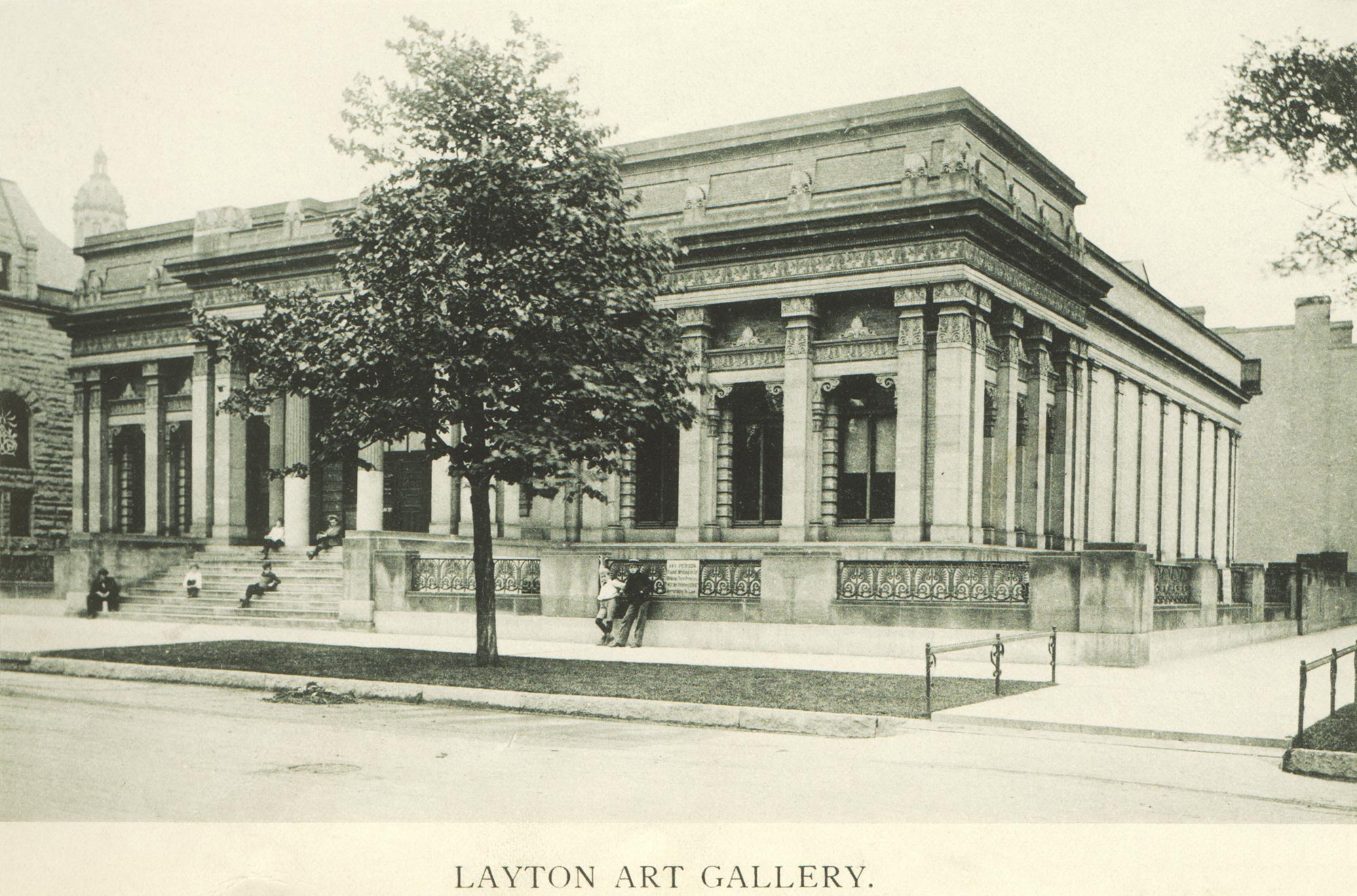

Bornstein made art even in kindergarten, and in his teens portrayed subjects from Milwaukee’s Jewish community: “I recall making drawings and paintings of some of the marvelous old men with long beards or women wearing babushkas and long skirts whom I saw in the Jewish fish markets and butcher shops on Walnut Street when going shopping there with my mother.” His mother especially encouraged his creativity. When he was around twelve, she enrolled him in the Saturday morning art classes at the Layton Art Gallery (which merged with the Milwaukee Art Institute in 1957). Bornstein wrote: “I recall how struck I was by the Greek columns, the marble sculptures like The Dying Gladiator, and the huge paintings on the walls. Here was a temple to art. The tranquility and exalted atmosphere left a lasting impression.”

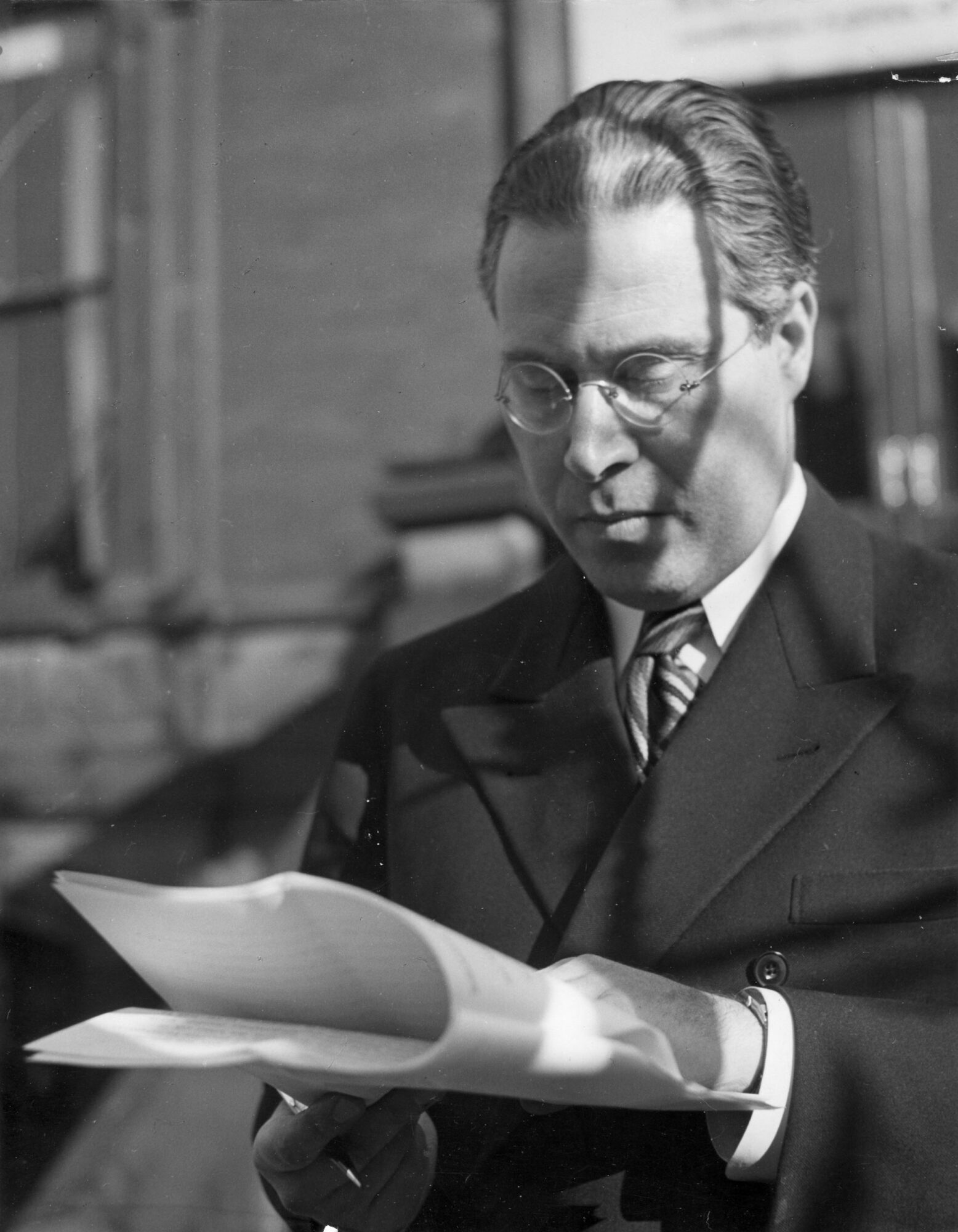

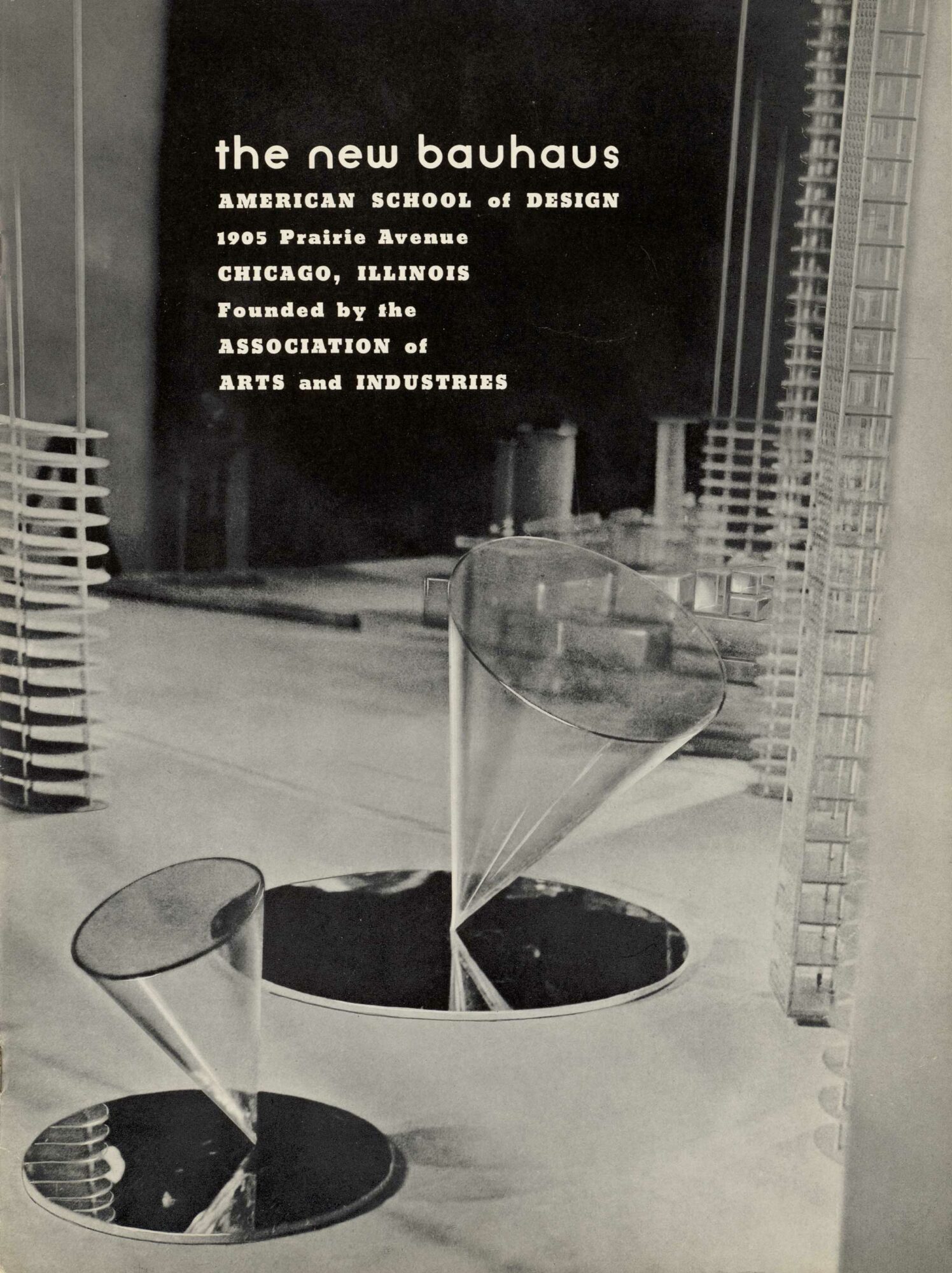

When Bornstein enrolled in his art courses at Milwaukee State Teachers College in 1941, the art world in Wisconsin was still quite conservative. But he remembers several teachers at the college who influenced him greatly: the historian F.E.J. Wilde, who guided him through the cultures of ancient Egypt and Greece; the German-born artist Robert von Neumann (1888–1976), who, although described as the quintessential Wisconsin Regionalist artist, introduced Bornstein to modern art from Impressionism to Cubism, with visits to the Art Institute of Chicago; and Howard Thomas (1899–1971), in whose design classes he learned about the Bauhaus and European abstract art. Thomas took his students to visit the School of Design in Chicago (founded in 1937 as the New Bauhaus), where they were introduced to its director, the Hungarian former Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946)—an important future influence—who gave them an extensive tour of the school.

All in all, as Bornstein has recounted, his lessons at the Milwaukee State Teachers College aroused his interest in literature, philosophy, and history and stimulated his understanding of the relationships between art, philosophy, and religion. As well, during his years at the college he developed a fascination with designing and building things: Bauhaus-inflected furniture such as a radio cabinet, a phonograph storage cabinet, and a bookcase. In jewellery-making classes, Bornstein became adept at working with brass and bronze, skills that he would apply when he made his first constructed sculptures in the mid-1950s, such as Growth Motif No. 4, 1956.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, despite being a conscientious objector, Bornstein briefly served in the U.S. Army infantry in Texas before being honourably discharged in 1943. After his service, he moved to Chicago. He knew the city not only from school trips, but also from many family visits with relatives since he was a child. Attracted to its energy, Bornstein enrolled first at the School of the Art Institute and then at the University of Chicago, where he took classes in anthropology and history. But, as he recollects, he was restless and uncertain about how to get on with his life as an artist, and his short stay in the city as an art student while working as a part-time labourer handling railroad freight “was an unsatisfying and lonely time which led me back to my home in Milwaukee where I resumed my college education.”

In 1945, Bornstein received a bachelor of science in art from the Milwaukee State Teachers College, and for the rest of the decade he taught drawing, painting, sculpture, and design at the Milwaukee Art Institute and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. In 1950, he accepted a position with the Department of Art at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. As he was pursuing a master of science degree in graphic techniques at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he had to travel back and forth between the two cities. He graduated in 1954.

Move to Saskatchewan

When Bornstein first accepted his teaching job at the University of Saskatchewan in 1950, it was a one-year contract substituting for a faculty member on sabbatical leave. He was then offered a permanent position initially responsible for all the studio classes. In 1957, Bornstein was appointed associate professor, and in 1959, he introduced a new program of both theory and studio-based courses entitled “Structure and Colour in Space,” as part of the Department of Art’s undergraduate and graduate offerings. The program became an area of specialization unique in North America and attracted many pre-architecture students. In 1963, he was appointed professor and until 1971 served as head of the department. After nearly three decades working in higher education, Bornstein retired from teaching in 1990.

As Bornstein remembers it, his introduction to the landscape of the Saskatchewan prairies was in 1950, when he took the train across the Midwest, from Milwaukee to Saskatoon. “I was overwhelmed by the space and the light. The space at first was almost unbelievable in its flatness and endlessness.” It was a visual geography perhaps not unlike that of Lake Michigan, but his encounter with the vastness of the lake took place from its shore, looking off at a distant panorama. Instead, on the prairie, he was in the midst of it, “almost lost within it or consumed by it.” As he recollects, “The prairie light was almost equally overwhelming. Its brightness and unique character, the prominence of the sky, the far greater daily consciousness of the unobstructed sun and the moon and the dramatic changes through the seasons—these were to become one of my greatest attractions to the prairie that has continued to enthrall by its power and diversity.”

When Bornstein first arrived in Saskatoon, he found that artists on the prairies still mostly embraced some form of realism relatively untouched by the revolutions in art that had occurred in Europe. Artists such as the British-born Henry George Glyde (1906–1998), then the head of the painting division at the Banff School of Fine Arts (now the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity), continued to work representationally using nineteenth-century British and European models, leavened with newer influences from the Group of Seven. There were, of course, exceptions. In 1950, when Bornstein arrived at the University of Saskatchewan, the newly formed art department at the University of Manitoba adopted modernist abstraction when it invited a small group of recent MFA graduates from the University of Iowa to form the faculty. The Winnipeg-based group included Richard Irving Bowman (1918–2001) and John Kacere (1920–1999), working variously in the modernist ways of the American Surrealist artist Gordon Onslow-Ford (1912–2003) and his circle; the printmaker Stanley William Hayter (1901–1988); and the Abstract Expressionists. There were other faculty members working in the style of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Cubist modes, and the venerable Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) also made his first abstract pictures in 1950. But the so-called Winnipeg Group flowered only briefly. While it received countrywide attention in the early-to-mid-1950s, the group faded from national sight with the departure of the Americans in 1953 and 1954 for warmer climates.

In Saskatchewan, the principal factors of change that brought modern art to the province were Bornstein’s appointment in Saskatoon in 1950 and the simultaneous hiring of Kenneth Lochhead (1926–2006) by the School of Art of Regina College (then a junior college affiliated with the University of Saskatchewan since 1934). But, because of Bornstein’s imminent commitment to working in the Structurist Relief, the two artists’ pathways would diverge dramatically. Over the next decade, Lochhead, through his faculty hires, brought together a group of artists—Ronald Bloore (1925–2009), Ted Godwin (1933–2013), Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994), Arthur McKay (1926–2000), Douglas Morton (1926–2004)—who eventually, as a consequence of a 1961 National Gallery of Canada exhibition, became known as the Regina Five.

The Regina Five were dedicated to modernist abstraction, but emphasized the flatness of the painting medium. Their work, variously known as “colour field” or “Post-Painterly Abstraction,” was, like Lochhead’s Dark Green Centre, 1963, typically large-scaled and composed with flat expanses of colour, the paint thinly applied directly onto the raw canvas or stained into it. The terminology was devised by New York art critic Clement Greenberg (1909–1994), who for several decades exerted a pervasive if controversial influence on abstract painting practice as well as curatorial taste in the West, a context within which Bornstein, dedicated to relief construction, would be cast as a relative loner. This may explain why Bornstein chose not to participate in the two-week-long Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops that Lochhead initiated in 1955 and which became for many decades an important fixture on the Canadian art scene. The workshops over the years were led by some of the most prominent Canadian and international artists including, famously, Barnett Newman (1905–1970) in 1959 and Greenberg in 1962. Bornstein himself explained that his summers were reserved for research travel.

An Artist on His Own

Bornstein, with his metropolitan experiences of Chicago and Milwaukee, may initially have found himself a bit isolated when he first arrived in Saskatoon. He knew little about Canada or Saskatchewan. But he also remembers being amazed to discover how much interest and activity there was in art and music and drama in this prairie city of around fifty thousand people. The university’s Department of Art was headed by Gordon Snelgrove (1898–1966), painter, art historian, and one of the first people in Canada to receive a PhD in art history. (He retired in 1962 when Bornstein replaced him.) As well, there were departments of music and drama; the city supported an impressive public library; and, as a political bonus, the province was run by the pioneering socialist Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) party and its social justice premier, Tommy Douglas, whose government introduced the continent’s first universal health care program.

The situation was further enriched when, two years later in 1952, Murray Adaskin (1906–2002) and his wife, Frances James (1903–1988), moved to Saskatoon. Adaskin, a musician and composer who was appointed head of the Department of Music at the University of Saskatchewan, helped make Saskatoon a major centre for the performance of contemporary Canadian music. James, in turn, was one of Canada’s finest soprano singers. Her regular recitals on the CBC premiered songs by many modern composers, both international and Canadian.

How Bornstein met James and Adaskin shortly after their arrival forms an amusing anecdote. During high school while working his daily paper route delivering the Milwaukee Leader, Bornstein fell into the habit of whistling along the way. It was a practice he continued as he walked to the university every day, passing the Adaskins’ house, “whistling away in the cold clear air of morning.” One of those mornings, as Bornstein tells it:

Murray came out on his front porch and stopped me. He wanted to know who was this young man that whistles Mozart so fluently…. That was the beginning of our life-long friendship and my admiration of those two extraordinary human beings from whom I learned so much about music, art, and life.

Bornstein, at this point a bachelor, lived with the Adaskins for about a year in their large house on University Drive.

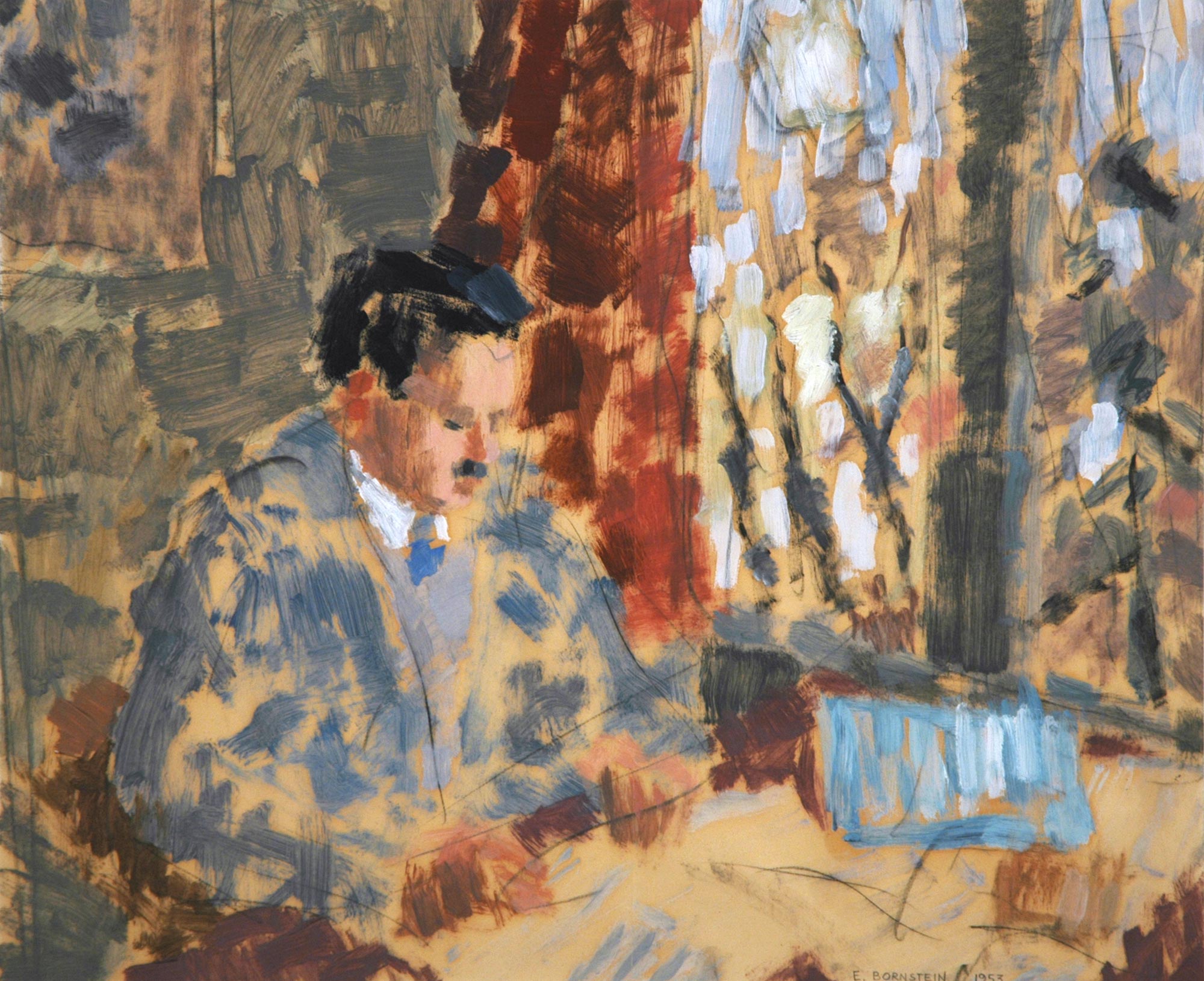

Bornstein spent the summers of 1951 and 1952 in France (as did many American artists in the postwar years) on grants from the American government under the G.I. Bill. During the first summer he enrolled at the Académie de Montmartre in Paris, which since 1947 was directed by the Cubist painter Fernand Léger (1881–1955); and in 1952 at the Académie Julian. These institutions had long attracted a large number of foreign students, but in both cases, Bornstein found their offerings unsympathetic to his own developing concerns. He much preferred working independently, setting off on his own around Paris, working out of doors, or visiting museums, following up the interests in Impressionism and in French modernists Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Paul Cézanne that he had cultivated at the Art Institute of Chicago. He also did some travelling outside Paris during these summers, venturing, as witnessed by the watercolour Boats at Concarneau, 1952, as far as the westernmost reaches of Brittany.

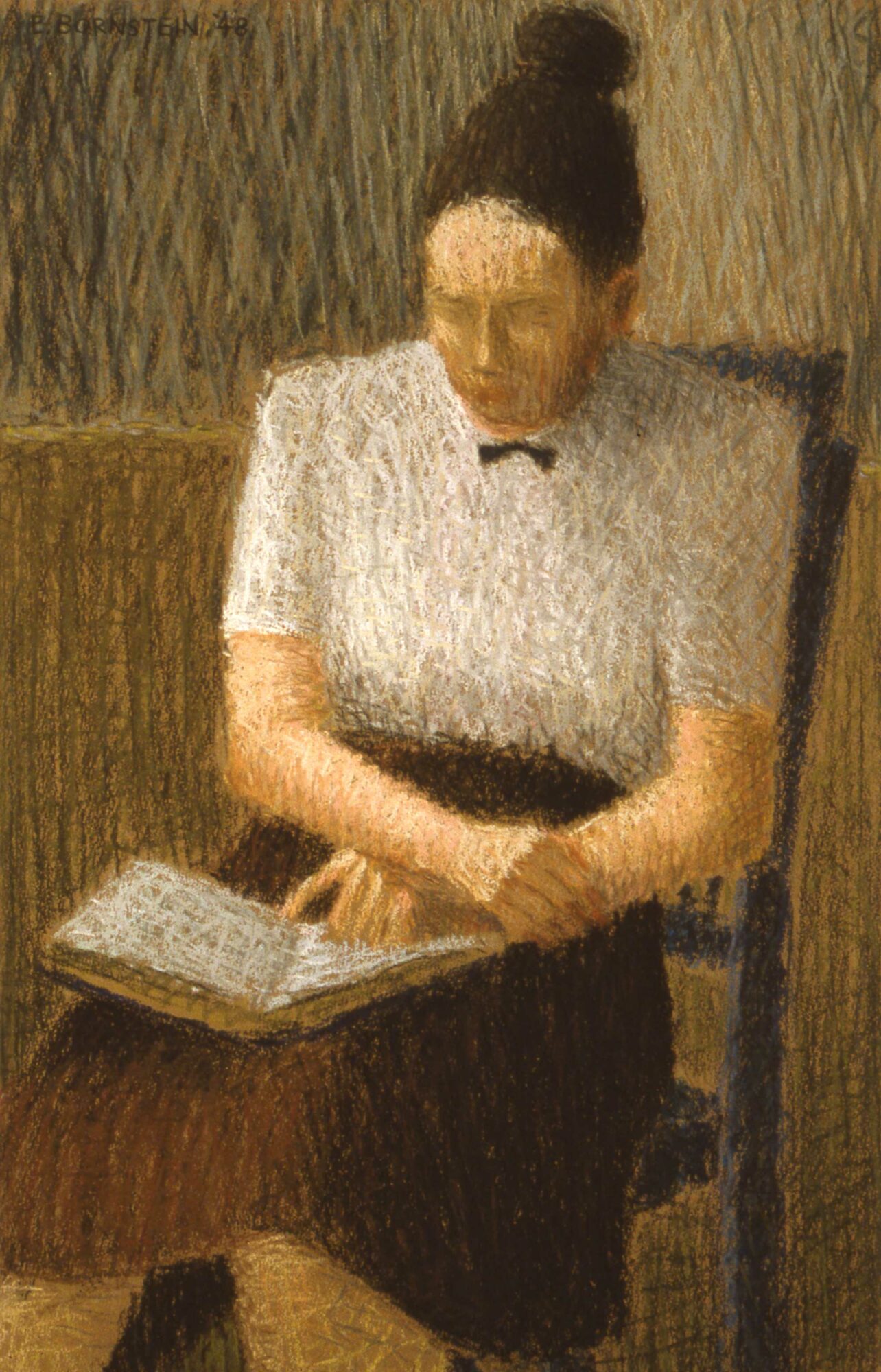

During the early 1950s, Bornstein’s favourite subjects, which he executed in large-scale watercolour paintings and in various print media, were the single female figure observed in interior settings, as in the pastel on paper work titled Girl Reading, 1948, and then landscape and city motifs. His interest in the styles of Post-Impressionism and Cubism culminated in a watercolour, The Island, completed on the coast of Maine in 1956. Concurrently, Bornstein made sculptures influenced by Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957) and the modern art movement known as Russian Constructivism. In 1947, his work Head—which was awarded a purchase prize by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis—led to his monumental public commission, Aluminum Construction (Tree of Knowledge), 1956. Despite this public recognition, no one from the art department supported Bornstein during a nasty letter campaign in the local newspaper that followed the installation of Tree of Knowledge. His public sculpture in front of the Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation Building in Saskatoon was attacked and deplored for being too abstract. Bornstein’s detractors even demanded that he be fired from the university. It was Murray Adaskin from the music department who spoke out in defence of both the artist and his work.

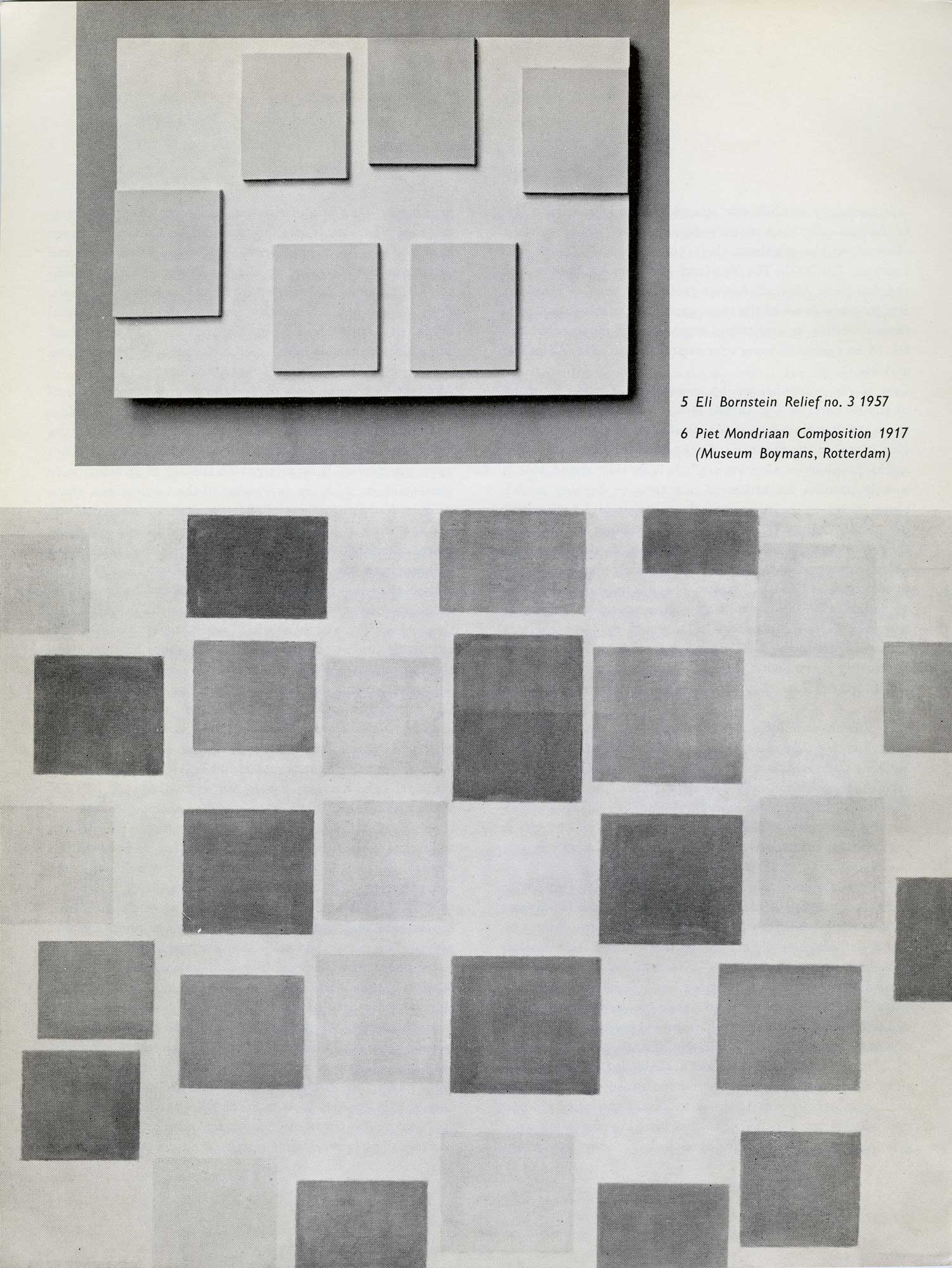

The Island and Tree of Knowledge would be Bornstein’s last representational or quasi-representational works before he turned his full attention to constructing his signature abstract reliefs. The transformation was not as abrupt as it may seem but followed his study of art history through Impressionism to Cézanne, and then on to Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) and the Dutch artist’s transition from nature-based imagery into pure abstraction, especially around 1916 and 1917. Then came Bornstein’s encounter with American relief artist Charles Biederman (1906–2004) in the mid-1950s. All of these experiences and lessons came together during his European travels in 1957 and 1958, when Bornstein made his own first abstract reliefs.

During the early 1950s, Bornstein also began to build his professional career, successfully being accepted, on both sides of the border, into the major annual and biennial survey exhibitions that then were standard programming for art museums in North America: at the Milwaukee Art Institute, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and the Winnipeg Art Gallery, among others. His first solo show took place in 1954 at the University of Saskatchewan, followed by another in 1957. In 1956, the University of Toronto’s Hart House (now the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery) held an exhibition titled Eli Bornstein: Graphics. Also that year, he received the Award of Merit from the Saskatchewan Arts Board in Regina.

Structurist Pathways

A decisive event of the mid-1950s was when Bornstein met the older American relief artist Charles Biederman, the pioneer, so to speak, of “Structurist art,” the nature-based branch of abstract colour-relief sculpture of which he would soon become a leading practitioner. Bornstein had heretofore had doubts about Biederman’s constructed reliefs, which he knew only in reproduction. But when in 1954 he read the latter’s voluminous book on art history and theory, Art as the Evolution of Visual Knowledge (1948), and subsequently his Letters on the New Art (1951), he was deeply impressed. In the spring of 1956, Bornstein contacted Biederman and started corresponding with him. When he subsequently discovered that Red Wing, Minnesota, Biederman’s home, was en route between Milwaukee and Saskatoon, Bornstein visited him on several occasions. Seeing Biederman’s reliefs in person made Bornstein realize that they were in fact related to his own interests.

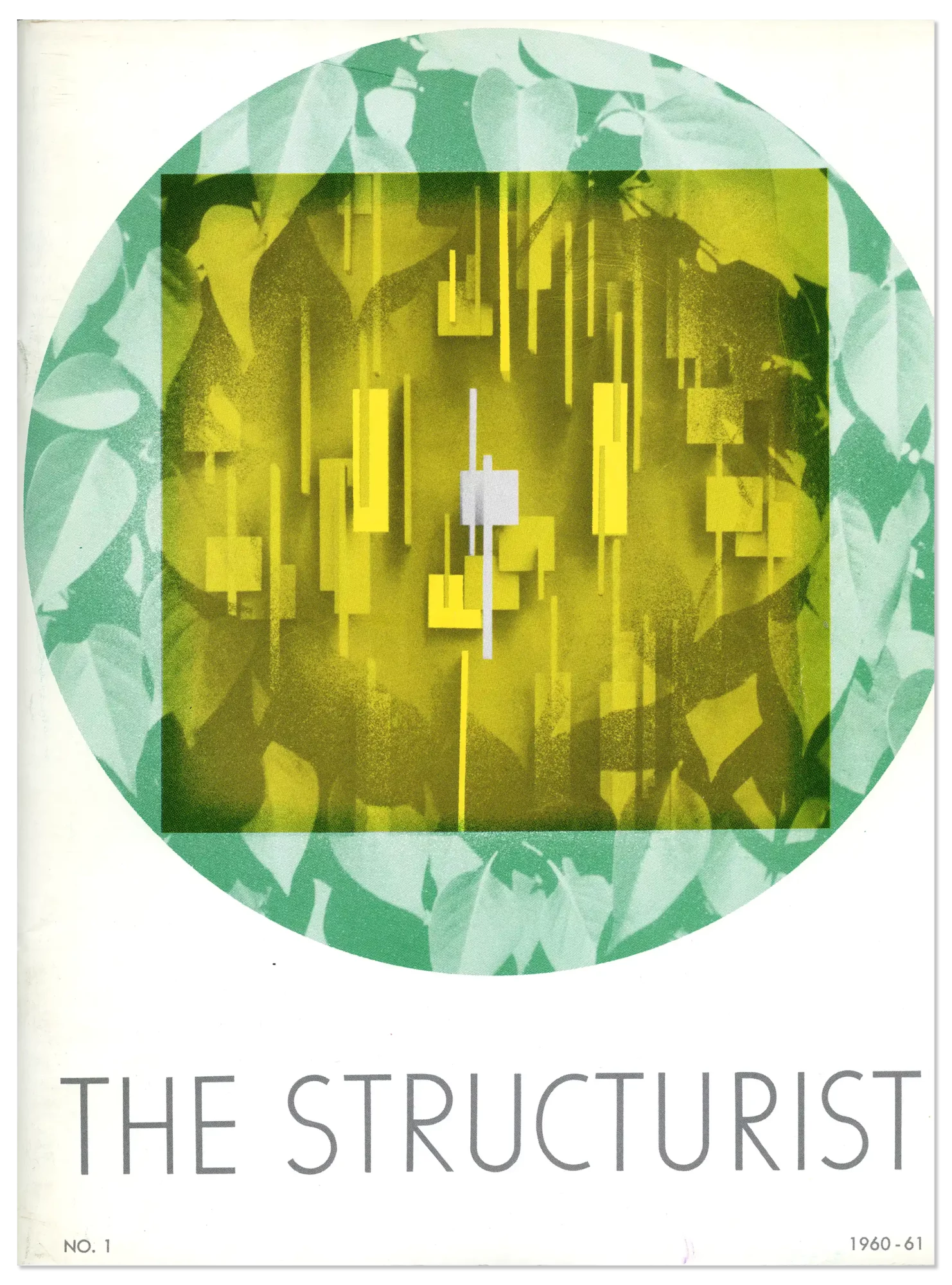

Three concepts in Biederman’s writings particularly appealed to Bornstein. There was Biederman’s systematic analyses of the evolution of modern art from its roots in Impressionism through to Constructivism and De Stijl, a pathway his own work had been negotiating. There was Biederman’s ongoing commitment to nature—regretting how the Europeans in their formal pursuits had banished nature from art in favour of idealistic or metaphysical pursuits—an obligation that would make Structurist abstract relief art a uniquely North American phenomenon. As Biederman defined it, the task of the artist was to translate “the building method of nature into art possessing precisely the palpable, corporeal qualities of nature—actual space forms.” And then there was how Biederman understood art as related to the larger society within which it was made: not art for art’s sake, but art in a broader cultural sense, a conviction that Bornstein would support throughout his many writings and in his editorship of the periodical The Structurist, which he founded in 1960 and published for more than five decades.

-

Jean Gorin, Spatio-Temporelle #23, 1966

Oil on wood, 99.7 x 99.7 x 8.5 cm

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon

-

Mary Martin, Spiral Movement, 1951

Painted chipboard, 45.7 x 45.7 x 9.6 cm

Tate Modern, London

While on sabbatical leave from teaching at the University of Saskatchewan, travelling in Europe during 1957 and 1958, with the specific purpose of studying Constructivism and De Stijl, Bornstein sought out many of the major European relief artists. In Paris, he visited Georges Vantongerloo (1886–1965), one of the founding members, along with Piet Mondrian, of De Stijl, an idealistic international alliance of artists, architects, and designers dedicated to creating an abstract visual vocabulary that, put to practical use, would communicate the way toward a peaceful and harmonious society. He also met Jean Gorin (1899–1981) who, in the mid-1920s, had pioneered relief constructions as an independent art form.

In London, he contacted the relief artists Kenneth Martin (1905–1984), Mary Martin (1907–1969), Victor Pasmore (1908–1998), and Anthony Hill (1930–2020); and in Amsterdam, Joost Baljeu (1925–1991). During Bornstein’s sabbatical, he also travelled in England, Denmark, Norway, and Spain, and lived for a while in Punta Marina, a seaside resort near Ravenna in Italy, as well as in Amsterdam, where in 1957 he made his first relief constructions.

Throughout this period of travel abroad, Bornstein found himself dissatisfied with the abstract geometry of European artists’ constructions. He saw Jean Gorin’s work too defined by science and technology and too based on mathematical principles, and missing, as he wrote to Biederman, “a strong and necessary relationship to nature.” In the same vein, Bornstein remarked on how the English confined themselves largely to unpainted industrial materials like plastic, Formica, stainless steel, and aluminum. While they took an interest in light effects, they had none in colour: that is, in colour as manifest in the structures of the natural world. As Bornstein later recalled about finding his own way, it was during 1957 in Europe that his dual interests in painting and sculpture finally came together: to find resolution in an abstract constructed relief medium, which could embrace “the space, form and structure of sculpture and the colour and light of painting.”

First Reliefs

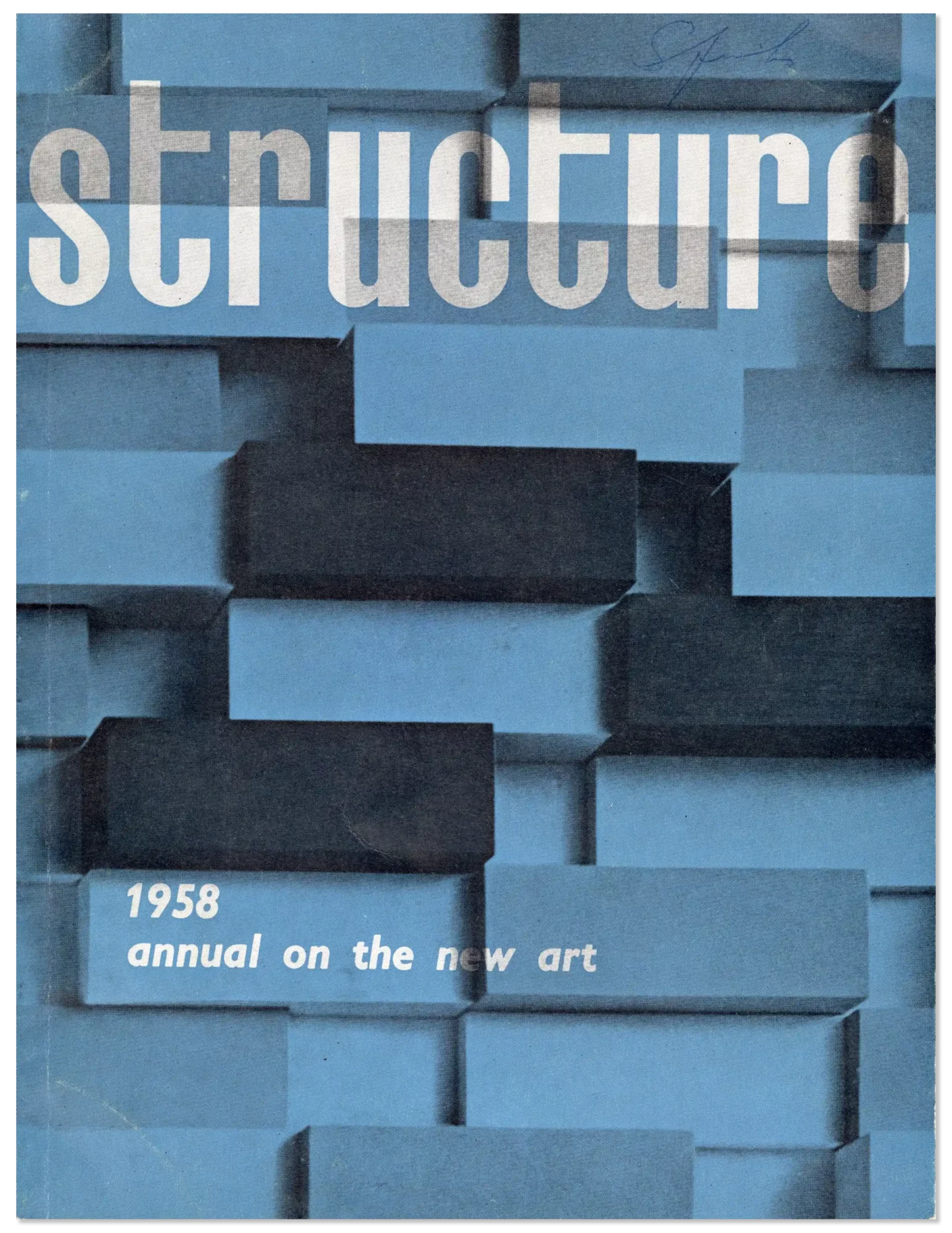

In 1958, following his breakthrough European sabbatical, Bornstein, back at the University of Saskatchewan, published an extensive iteration of his newly formulated aesthetic theories in the first issue of the periodical Structure: Annual on the New Art. Structure was co-edited by Bornstein and the Dutch relief artist Joost Baljeu, who that year was a guest lecturer at the University of Saskatoon; also included were articles by Charles Biederman and the contemporary German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007). The issue was in effect a mission statement, if not a manifesto, for the “New Art,” as they called it, until, later in the year, Bornstein adopted Biederman’s terminology of the Structurist Relief.

After having co-edited the first issue of the periodical Structure in 1958, in 1960, he inaugurated his own internationally circulating journal, The Structurist, published out of the University of Saskatchewan, and appearing annually until 1972 and then biennially until 2000, with anniversary issues in 2010 and 2020. The Structurist, which drew on a roster of distinguished international writers, began, as Bornstein described it in retrospect, “as a forum dealing with the future of art and architecture, concerning interdisciplinary subjects related to many neglected considerations of how art evolved and was related to many other subjects such as science, technology, culture, education, music, etc.”

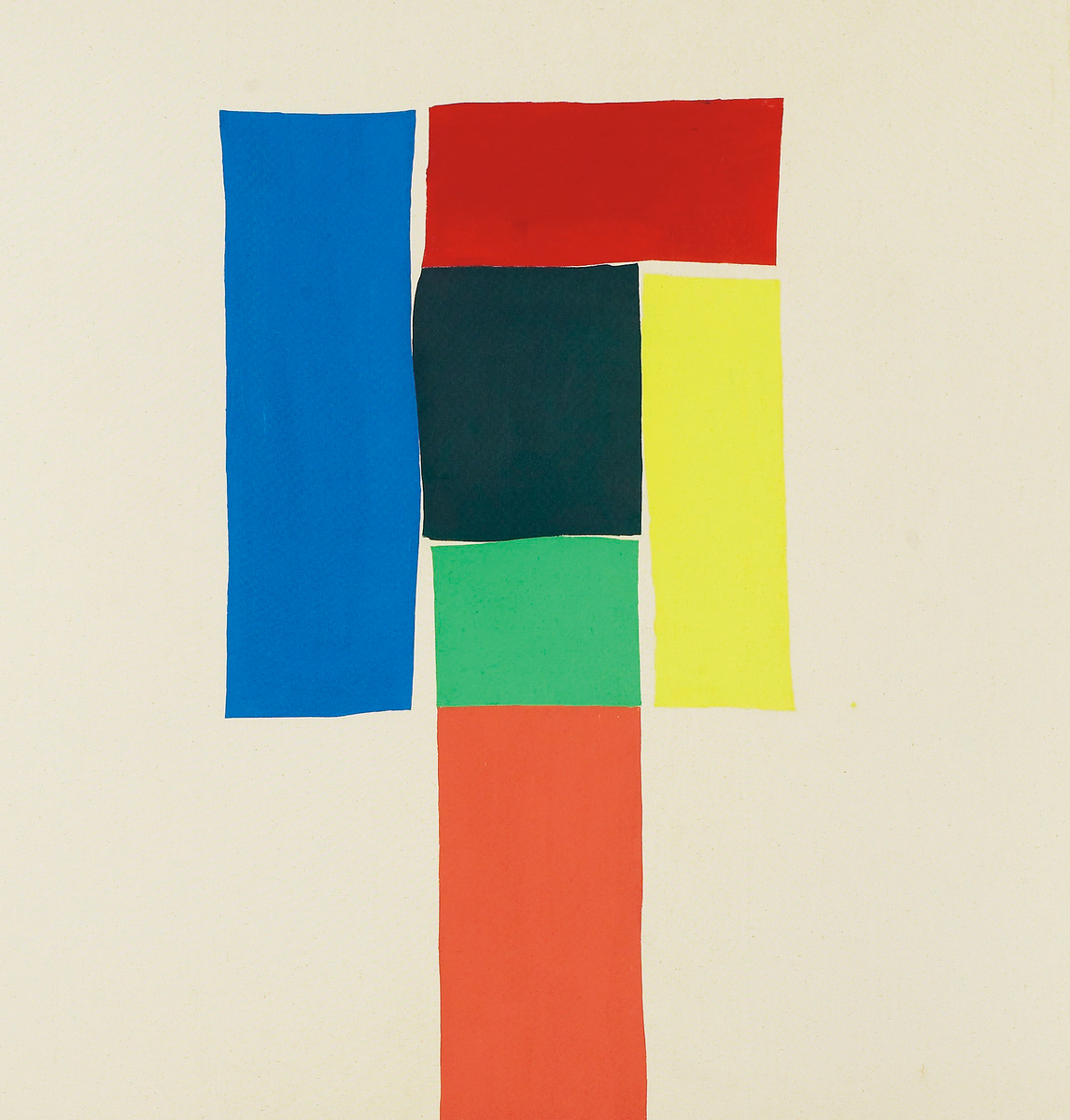

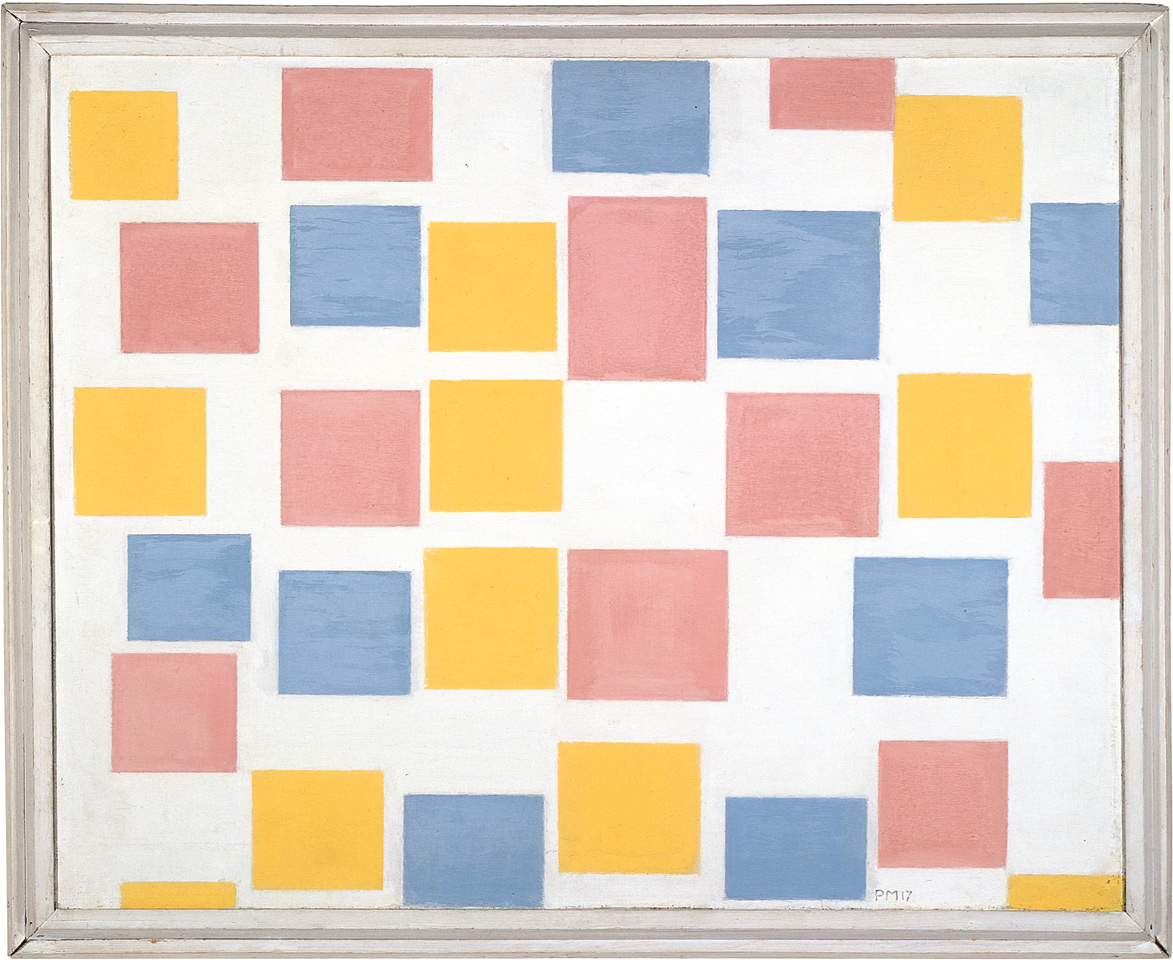

While the journal circulated Bornstein’s ideas about Structurist art through the written word, his own reliefs had first been made the year before, in 1957. They were modestly constructed out of tempera in composition board or oil on wood, and composed of low, relatively large rectangles splayed out in asymmetrical compositions across a neutral background support plane. They are, as in Structurist Relief No. 4, 1957, mostly white on white with the addition of one or more primary colours. Their sensibility is Bornstein’s own, but he does not yet stray far from the European De Stijl tradition, with its emphasis on colour and rectilinear geometry. Indeed, in the inaugural issue of Structure, on page 36, he tellingly juxtaposes one of his first 1957 reliefs to Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Color Planes 2, 1917, a model he had already applied the year before in the across-the-surface dispersed composition of The Island, 1956.

Here was the start of what would be Bornstein’s unwavering commitment to the evolution of the Structurist Relief as it launched the colour dynamics of painting into the sculptural world of space and light. Over the next six decades, he would steadfastly enhance its compositional potentials and enrich its expressive depths. Step by step his formal elements would become more diverse, their relationship and rhythmic interplay more complex and their colours more manifold, the reliefs increasingly resonant with the diversity of nature’s unfolding, always the subject of his intense daily study.

The 1960s saw the first of many solo exhibitions of Bornstein’s Structurist reliefs, including in 1965 and 1967 at the Kazimir Gallery on Michigan Avenue in Chicago. Kazimir Karpuszko (1925–2009) was a young art dealer, author, and curator who had become involved in the Structurist art movement. In 1968, he was instrumental in the group exhibition Relief/Construction/Relief, which opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and toured through the eastern United States. Karpuszko’s commitment to Bornstein’s work would persist into subsequent decades and, in 1982, he would curate Eli Bornstein: Selected Works / Œuvres choisies, 1957–1982 for the Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, an exhibition that toured to the Art Gallery of York University, Toronto, and other venues in eastern Canada, as well as to the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

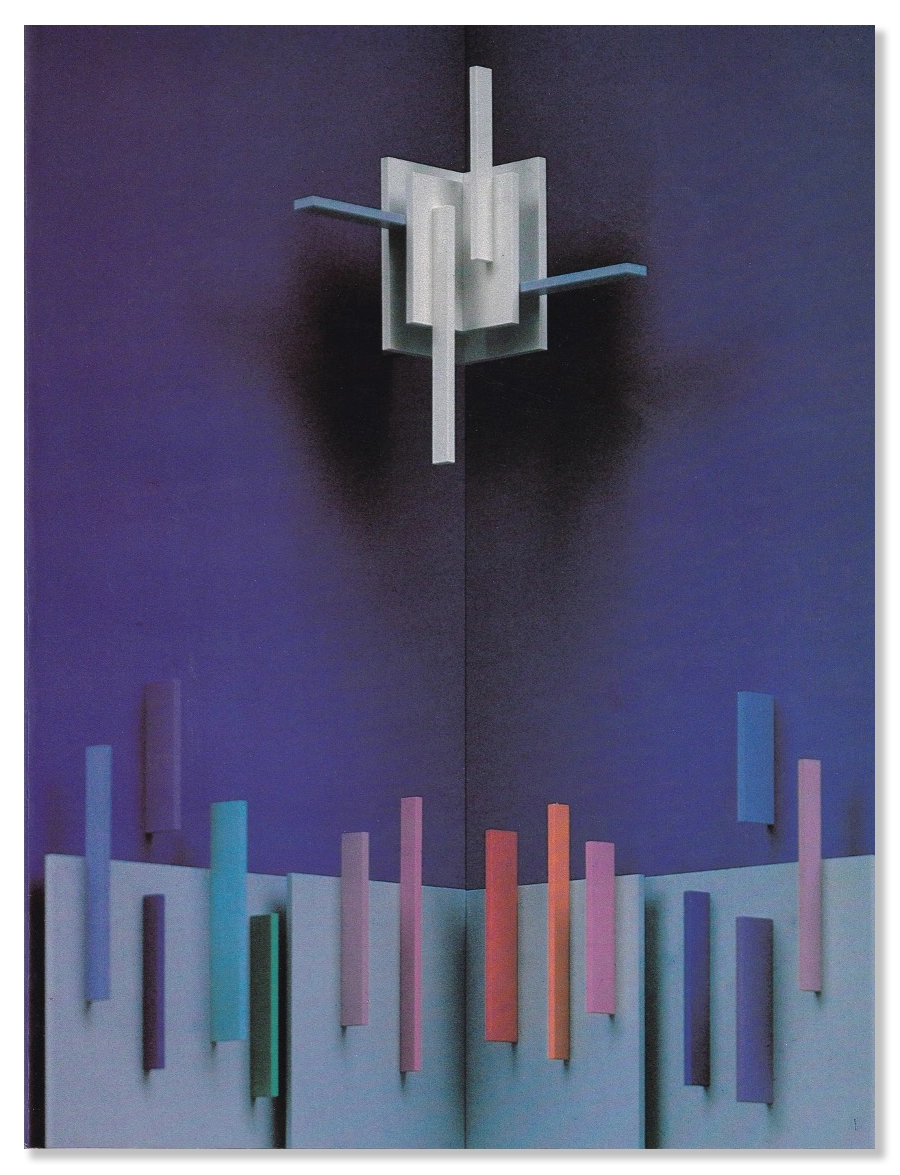

A Time of Innovation

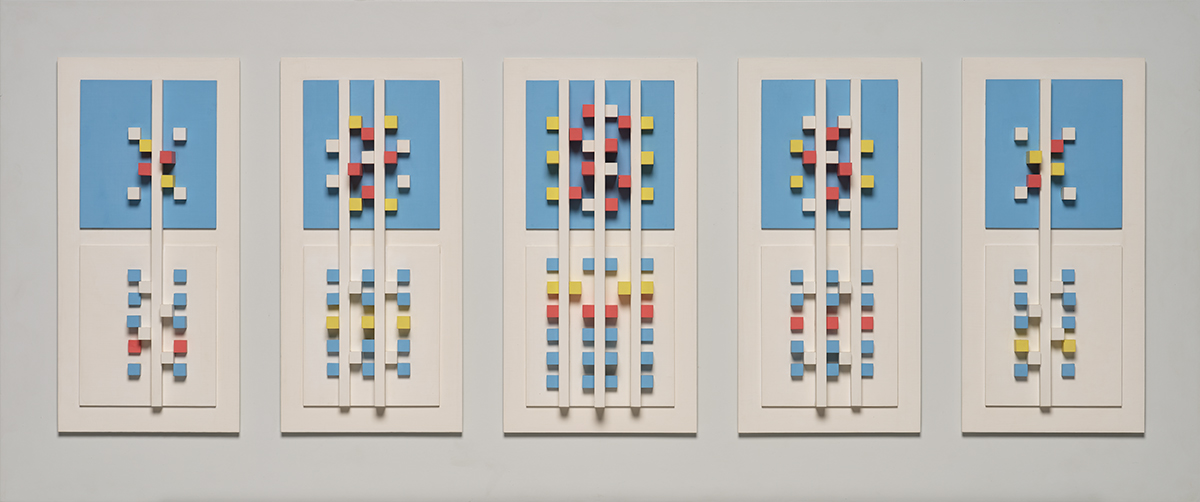

As Bornstein’s European journey in 1957 and 1958 had proven, summers and sabbaticals, unburdened by teaching and administrative duties, were valuable times for travel and research, and opportunities for concentrated creative innovation, which he took advantage of throughout the 1960s. During this time period, Bornstein also constructed a federal government commission for the new Winnipeg International Airport, a work entitled Structurist Relief in Fifteen Parts, 1962. When the terminal was demolished some four decades later, the sculpture was removed, restored, refinished for exterior use, and reinstalled in 2014 on the facade of the Max Bell Centre at the University of Manitoba. A model version of the work, titled Structurist Relief in Five Parts, 1962, had been purchased by the National Gallery of Canada in 1965.

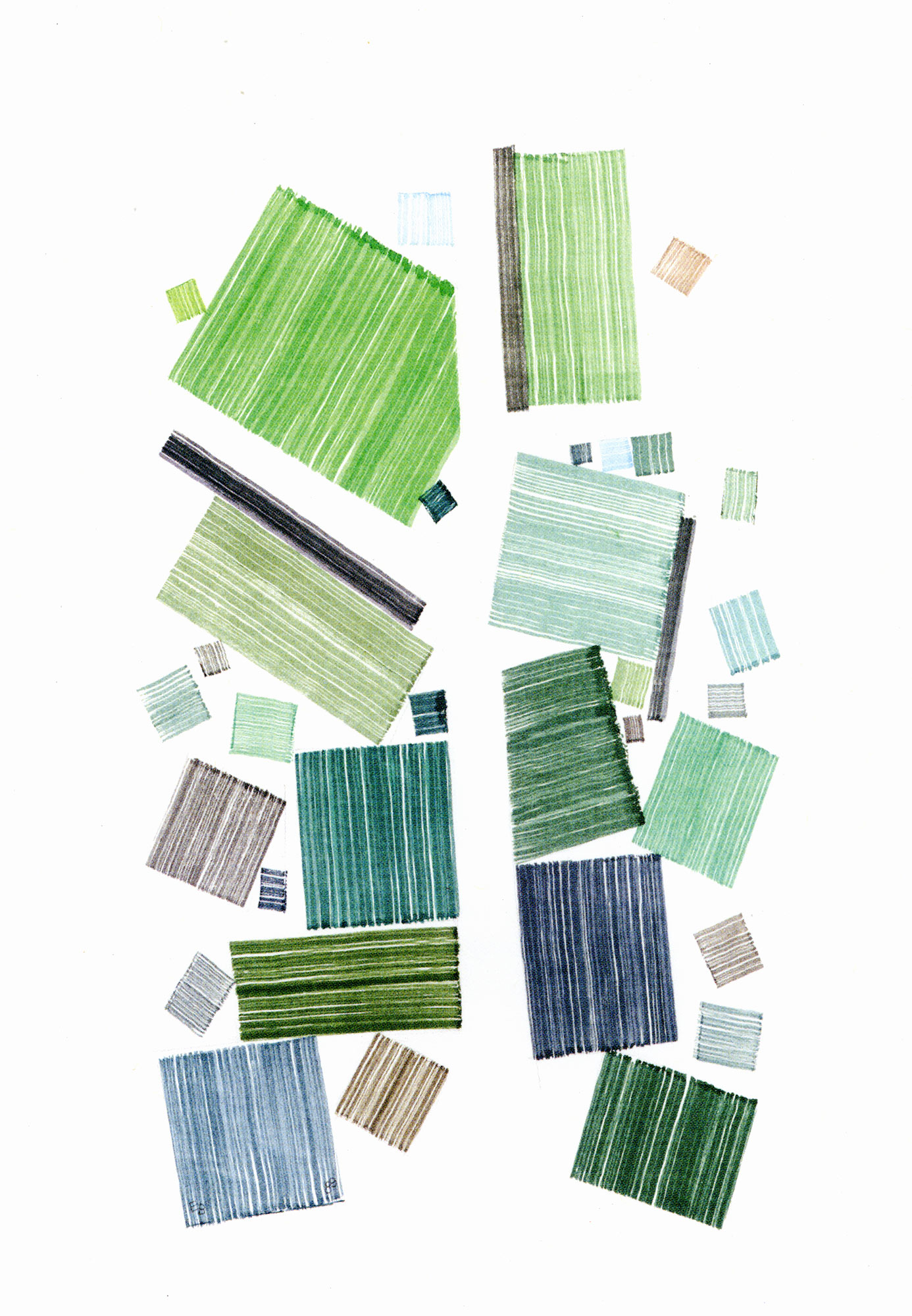

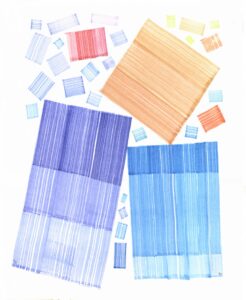

Innovation also came through the production of two important series created from 1964 to 1967: the Canoe Lake Series and the Sea Series. Both series exploited Bornstein’s newly liberated colour palette, as the artist also honed his ways of making foregrounds and backgrounds conjoin and interact.

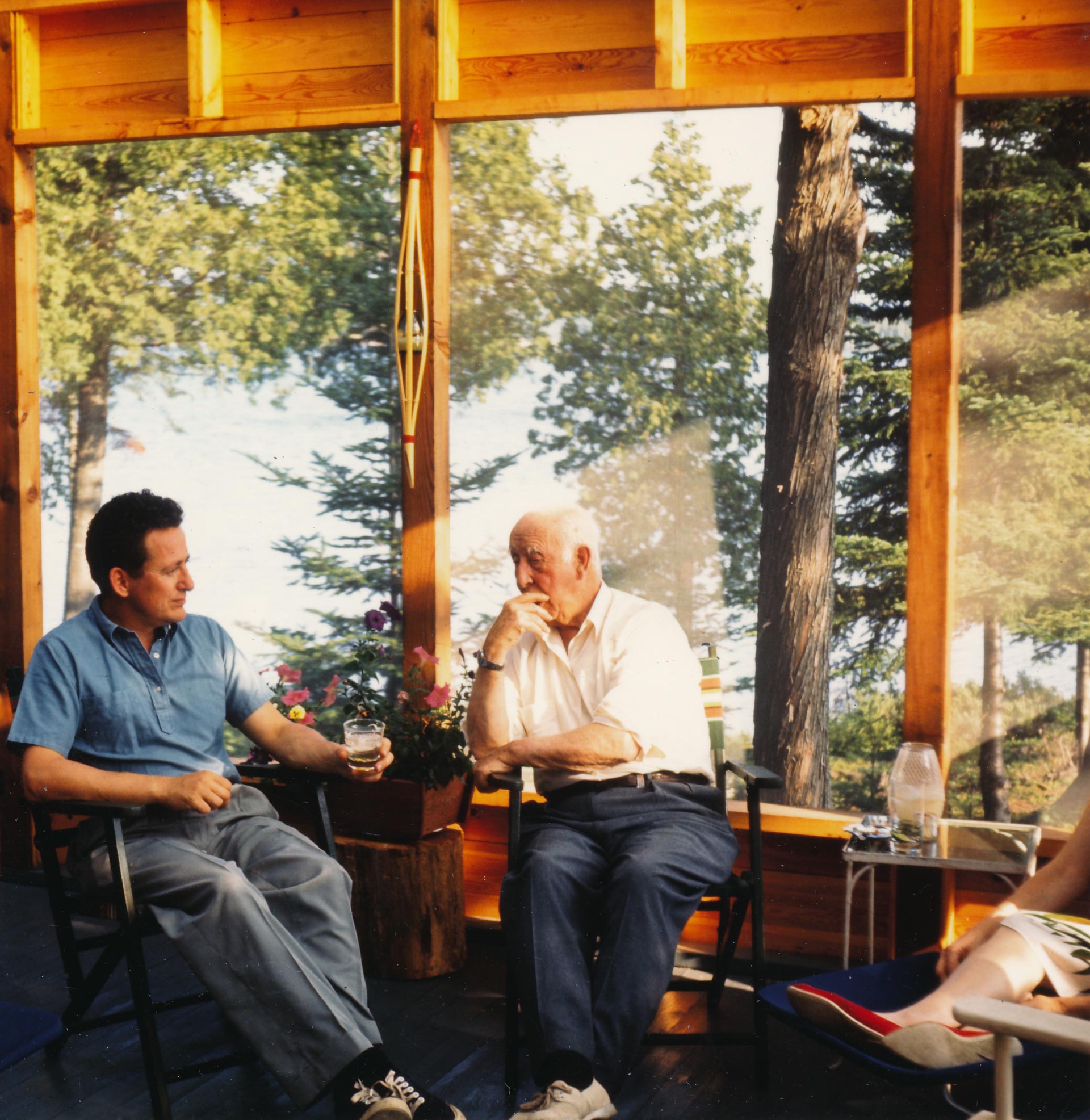

The Canoe Lake Series, begun in 1964 (and named after the celebrated place where Tom Thomson [1877–1917] painted), originated in Algonquin Park, where Bornstein spent the summer in a cabin owned by a friend of Murray Adaskin. The reliefs’ layered constructions, their deep plays of light and shadow, and their colour orchestrations, now freed from the primaries, evoke lakeshores and the foliage of deep woods. Bornstein’s growing propensity for colour complexities was something of a departure from more Structurist orthodoxies, which Charles Biederman had warned him about rushing into. Fittingly, during that July, Bornstein met up with A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) when the Group of Seven painter was on a short visit to Algonquin Park. A photograph shows the two artists in conversation seated before a window in Adaskin’s own cabin.

As Structurist works of the early 1960s, the Canoe Lake Series reliefs are a little atypical for the period in that they quite squarely occupy the whole of their white background planes. In contrast, Bornstein’s Structurist Relief No. 1, 1966, was more usual, its relief elements clustered toward the centre, leaving the support plane largely neutral, its corners empty. This was the common way to compose, as we can glean from the illustrations in an article titled “Structurist Art,” published in May 1967 in the magazine Chicago Omnibus. The article was dedicated to the new generation of artists who were following in the footsteps of Biederman and Bornstein. Working in the United States were William Jordan, David Barr (1939–2015), and Lawrence Booth; in Canada, Ron Kostyniuk (b.1941), Don McNamee (1938–1994), and Elizabeth Willmott (b.1928), the latter of the three among the most prominent of Bornstein’s students. The Chicago Omnibus article further described the Structurist movement in 1967 as “a New World phenomenon now based at the University of Saskatchewan.”

Another innovation came with Bornstein’s Sea Series, in which the artist was clearly seeking new ways to animate his support planes. In these works, he stretches his now larger, flat component colour planes outward until they more fully occupy the background plane, reaching out into its four corners (see, for example, Structurist Relief No. 3 (Sea Series), 1966–67). Here Bornstein is not only taking another important step toward enlivening those ground planes, but he has also taken prescient steps toward defining the terms of his own individual stylistic and expressive pathway forward.

The Sea Series as well as the concurrent Double-Plane reliefs originated in 1966 to 1967, in California, where Bornstein spent a sabbatical year away from teaching, living near Big Sur on a mountaintop overlooking the Pacific Ocean. A journal entry recalls how his eyes “opened daily to an immense sky above and the great Pacific Ocean below that could as well have been the great prairie plane of Saskatchewan.” The solution of the Double-Plane reliefs was to fold his ground planes down the middle at 45 degrees as if they were half-opened books, in effect to enfold them and bring them inside. This seemed simple enough in its own way, but it complicated exponentially the task of composing the multiple colour components that were now nested between their also coloured pages, those thin tiles of colour that thrust themselves dynamically into space and were observable from multiple angles.

During this period of innovation, in 1969, Bornstein and his wife, Christina, née Girgulis, librarian and actress—they were married in 1965—built their modernist house, low and ground-flung in harmony with the prairie flatness. It featured long rectangular skylights above the major hanging walls that allow the changing daylight, from morn to dusk and through the seasons, to illuminate the reliefs installed below. The house was situated next to the South Saskatchewan River, which Bornstein describes as “an unfolding ribbon or screen of colour” that reflects back the continually changing phenomena of nature: slow and constant in its underlying geographical wholeness before which and within which life, light, and colour endlessly change. The prairie riverbank is “my school and my church,” Bornstein writes.

The Impact of the Arctic

Among Bornstein’s travels were three foundational trips to the Canadian Arctic, the first in 1964 with Murray Adaskin and the anthropologist Bob Williamson. Subsequently, during the summers of 1986 and 1987, he returned to the Arctic again, this time with his University of Saskatchewan colleague the photographer Hans Dommasch (1926–2017). Out of those latter two summers emerged an exceptional body of drawings, paintings, and, back home in the studio, a series of Structurist reliefs such as Hexaplane Structurist Relief No. 2 (Arctic Series), 1995–98. He kept a journal—the Arctic Journals, which eventually ran to some 24,000 words—in whose pages Bornstein recorded eloquently his explorations of the macro-landscape of the fjords, glaciers, and icebergs, and the micro-landscape of moss, lichens, and Arctic flowers.

Bornstein kept a journal through most of his life, writing in longhand; but, beginning with the Arctic Journals from 1986 and 1987, he began to have it formally transcribed. His journal entries from 1990 up to 2017 run to 1,136 typewritten pages recording his thoughts on life, and on art in the context of the larger natural and human world. Rich in autobiographical reminiscences and eloquently poetic descriptions of nature, they form an intimate panorama of Bornstein’s exterior and interior universes. In the concluding paragraphs of his Arctic Journals, he writes about the profound impact of his northern experiences:

Somehow, clarity of vision and purpose seem more attainable in the Arctic. The wildness … or the wilderness … remain the ultimate hope for our survival or preservation in revealing what is most important. It makes or allows one to see more clearly that character is the supreme beauty. True character refers to genuine essence. It is a kind of identity that is unequivocal and fundamental—neither superficial nor pretentious—and as such is surely the highest form of beauty. The Arctic still has that power of essential character that can inform and instruct us without distraction. It can reveal to us a sense of identity with the earth and all living things that modern living tends to dispel.

This is exalted language that rises into incantation, a kind of “inner seeing,” as Canadian artist Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970) might have said. Certainly, the Arctic paintings by both Harris and A. Y. Jackson from their travels in the summer of 1930 were somewhere on Bornstein’s mind as he set out for Ellesmere Island. Indeed, only a few days after his arrival, he threw down the competitive gauntlet to his Group of Seven predecessors, convinced that his Structurist methods could more authentically embody northern nature than the representational paintings of Harris and Jackson. But, compare Harris’s Icebergs, Davis Strait, 1930, to Bornstein’s Multiplane Structurist Relief IV, No. 1 (Arctic Series), 1986–87: even though the two artists interpreted the Arctic in stylistically different ways, they saw their icy landscapes with shared eyes. The cold palette of Harris’s painting registers the same iridescence, the same brittleness, the same clarity, and the same silence that will characterize Bornstein’s Structurist reliefs, with their Plexiglas components. There is true kinship here.

In 1987, Bornstein showed his watercolour studies from the Arctic at the Art Placement Gallery in Saskatoon, and in 1990, again at Art Placement, his studies from a 1988 trip to Newfoundland, along with his 1989 Riverbank Studies watercolours executed in his own South Saskatchewan River backyard.

Major Exhibitions and a Life in Art

At the time of this book’s publication, Bornstein continues, in the twenty-first century, to expand on the potentials of the Structurist Relief, initiating a new body of work he titles Tripart Hexaplane Constructions. Like sculptures, they are walk-around, built out of three 320-degree Double-Plane reliefs backed up against one another and raised on a slim aluminum pedestal. But unlike sculptures-in-the-round, they reveal themselves only part by part as we circle them. It is with the long horizontal Multiplanes, however, whether seen individually, or as the tour de force River-Screen Series triptych, 1989–96, that the reliefs reach states of transcendent sublimity.

Alongside many group exhibitions, north and south of the border, that have celebrated Bornstein’s contributions to modern art, the Mendel Art Gallery gave Bornstein a second retrospective in 1996, Eli Bornstein: Art Toward Nature, curated by the Dutch art historian Jonneke Fritz-Jobse, and in 2013, a third large-scale show, An Art at the Mercy of Light: Recent Works by Eli Bornstein, curated by Winnipeg art historian and frequent insightful writer on Bornstein, Oliver A.I. Botar. The installation took full advantage of the Mendel’s skylit galleries, the experience well captured in the catalogue by Troy Mamer’s photographs of the installation. In 2019, the Remai Modern in Saskatoon staged a mini-retrospective, Artist in Focus: Eli Bornstein, with works drawn from its own collection and from the artist’s home and studio.

On the private gallery scene, there were exhibitions at the Forum Gallery in New York (2007) and in galleries in Saskatoon, Vancouver, and Victoria. As well, since the Tree of Knowledge, Bornstein has completed important public commissions in Winnipeg, Regina, and Saskatoon, including his monumental Four Part Vertical Double Plane Structurist Relief (Winter Sky Series), 1980–83, for Regina’s Wascana Centre. His major awards since 1956 include the Allied Arts Medal, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (1968); D.Litt., University of Saskatchewan (1990); and the Saskatchewan Order of Merit (2008). As a culminating honour, in 2019 he was inducted as a Member of the Order of Canada in recognition of his “boundless creativity,” and for how “his approach sheds light on current environmental issues.”

But finally, even as we evaluate Bornstein’s Structurist reliefs—their stylistic evolution, their industrial precision, their luminous palette, their obeisance to nature, their grand historical resonances—we must remember that they are also, as the critic Steven Cochrane observed, reviewing An Art at the Mercy of Light in the Winnipeg Free Press, “emphatically, unapologetically beautiful.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements