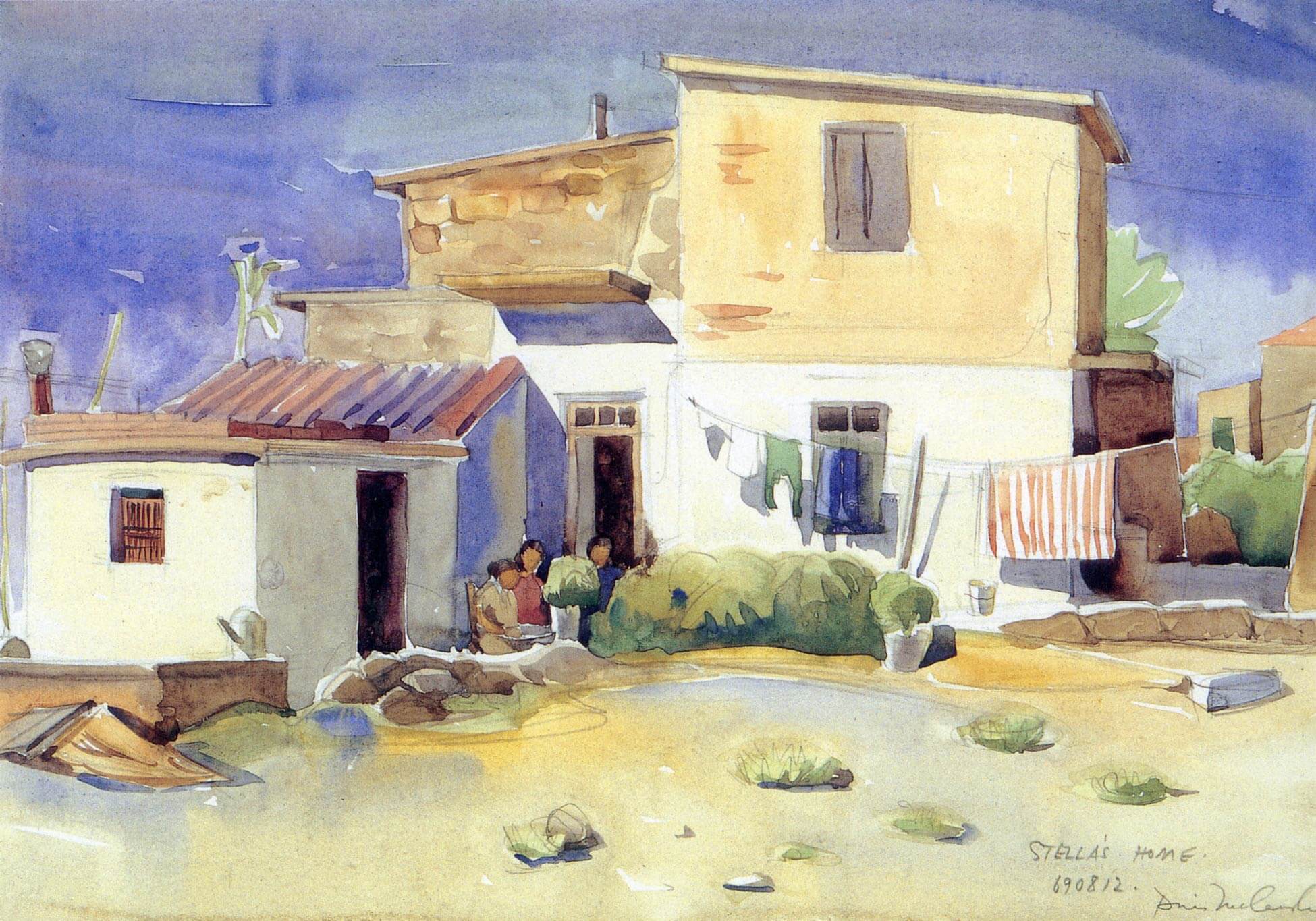

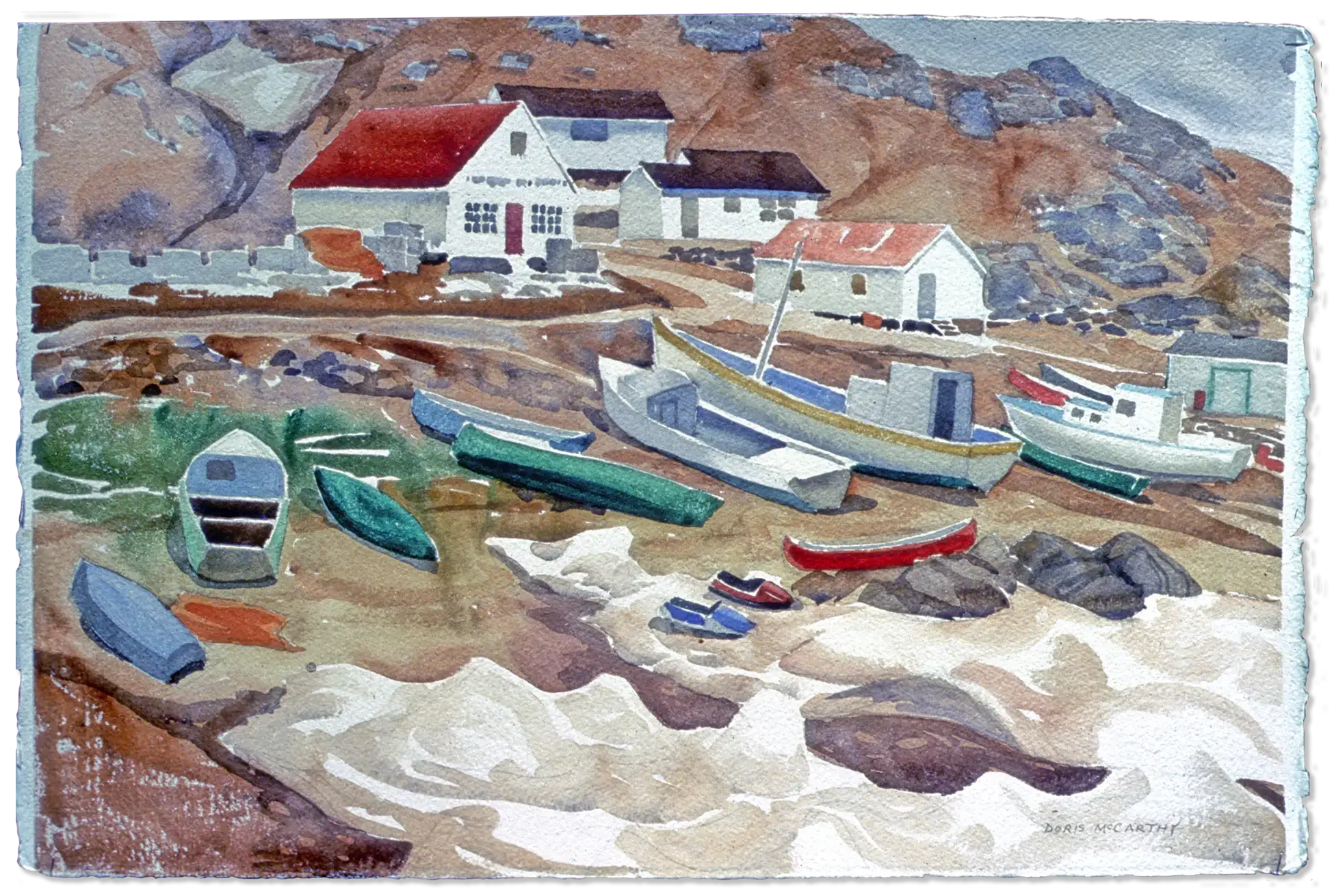

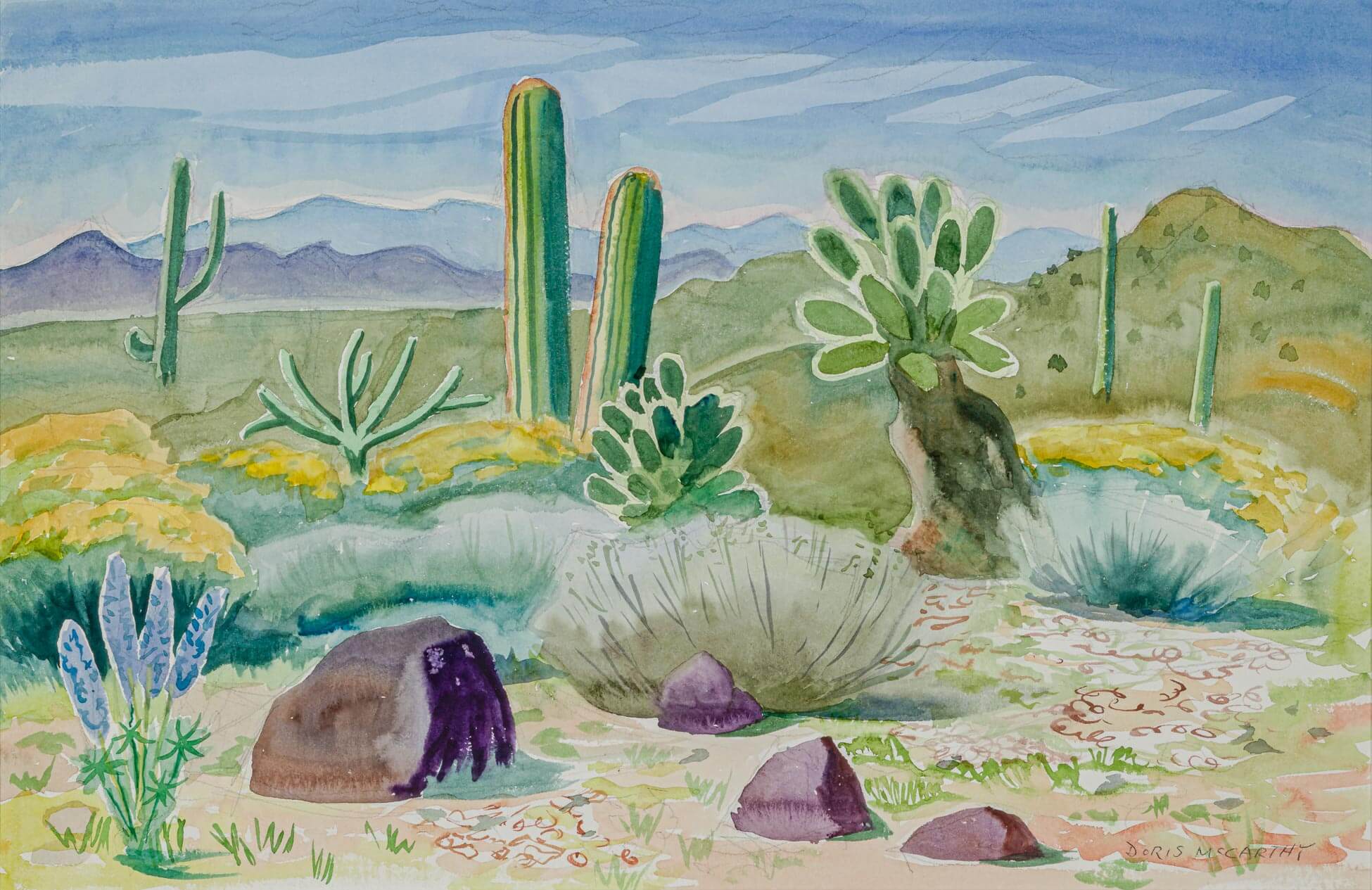

Nomadic as a traveller, Doris McCarthy was just as restless when it came to painting. She adapted her style to suit her subjects, always trying to capture the look and feel of a place. Not surprisingly, she insisted on working en plein air, using photographs as a reminder of her emotional response to a place. She always composed her works carefully, either by selecting what she wanted to paint or subtly manipulating a scene. Some of these qualities were inherited from the Group of Seven, whose shadow loomed large over her career, but over time she established her independence.

A Variety of Styles

Although by the end of her life McCarthy was well known for her pared-back and simplified landscape paintings, throughout most of her career, she worked in a variety of styles. She was influenced by the scenes she chose to paint, so, unlike Tom Thomson (1877–1917), Emily Carr (1871–1945), or Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970), for instance, her art varied stylistically from place to place. One critic dubbed her the “chameleon of the canvas.”

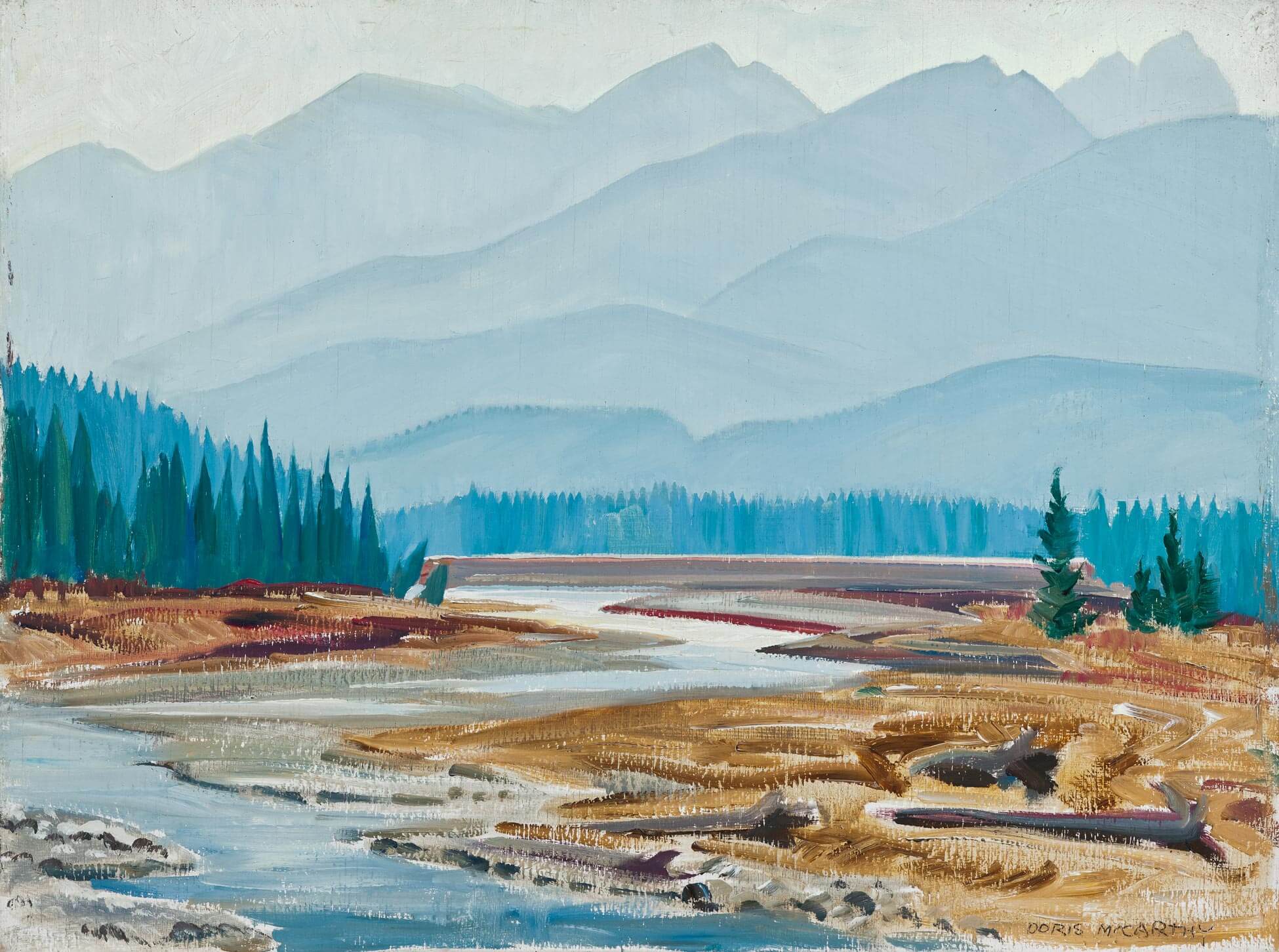

McCarthy wanted to represent each landscape faithfully, without any preconceived notions. When asked about her affinity to Harris, for instance, she responded that he “was more interested in art than he was in mountains. I’m more interested in mountains than I am in art.” The paintings she made during her world travels attest to the accuracy with which she read each location, whether peat bogs in Ireland, the Dal Lake in India, or the Colosseum in Rome. She captured not only the appearance of a place but also its “feel.” One common feature is the abstracting quality in her work, a sort of shorthand that doesn’t dwell excessively on details.

At times, McCarthy experimented with different styles, such as in her highly coloured “post-Romano” paintings like Hills at Dagmar, 1948, or in her hard-edge landscapes or iceberg fantasies, such as Iceberg Series 2, 1972. She did so partly to be skilled in a variety of techniques as she taught her students at Central Technical School: “[On occasion] I experimented with all the ‘isms.’ When I was teaching senior painting students, those ideas [were] important…. They enrich your vocabulary. But I abandoned most of the ‘isms’ as soon as I started painting myself.”

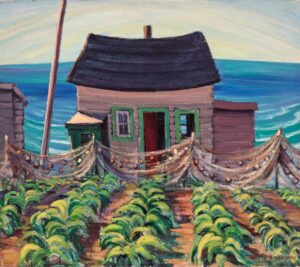

Doris McCarthy, Hills at Dagmar (aka Farm in Dagmar Hills), 1948, oil on canvas, 61 x 68.6 cm, location unknown.

Doris McCarthy, Hills at Dagmar (aka Farm in Dagmar Hills), 1948, oil on canvas, 61 x 68.6 cm, location unknown.

McCarthy was reluctant to credit the influence of other artists who had some impact on her approach, but she did add pieces of their individual styles to her arsenal of techniques. Early on, for example, in her first exhibited work, View from the Toronto General Hospital, 1931, it’s clear that the buildings in the foreground adopt a style similar to Harris’s depictions of the city, while the distant winter background recalls a nineteenth-century academic style.

Others who influenced her included Hortense Gordon (1886–1961), particularly her lessons on composition using a receding zigzag pattern; some members of the Group of Seven; and Henri Matisse (1869–1954), especially his use of colour and simplified forms. The fluidity of her approach gave McCarthy the freedom to go in different directions and not, like Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002), get stuck in a style demanded by collectors—in his case, 1960s bluish-green landscapes. McCarthy, in contrast, could paint whatever she wanted and in the way she preferred. The result is a richly varied body of work that exudes a love of painting equal to her love of the land.

Photography as a Tool

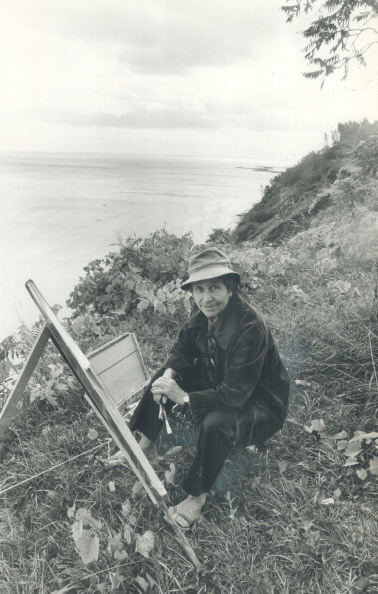

There are many photographs of McCarthy painting on site, outdoors. The one she treasured most depicts her painting in the Far North. It highlights the intensity with which she strove to capture the essence of her subject in both appearance and character. Before she began sketching, she spent considerable time studying a place and getting a feel for it. When she travelled to the Canadian Badlands in Alberta to paint the hoodoos, for example, she waited until she developed an affinity for that strange landscape before painting it. As she wrote: “Painting demands concentration and sensibility that grows into an intimacy with the country, greatly intensifying your awareness of it.”

McCarthy frequently took photographs of the places she was painting, especially later in life. However, she did not paint from the photographs she took without having first engaged with the landscape in paint. She considered working directly from photographs “the lazy way… and it’s not as good. When you’re working on the spot you’re in a relationship with your subject, which is quite different than working from a two-dimensional record of it.” She did, however, use the camera to record how the landscape constantly changes its appearance and how the light and the air can suddenly change.

Photography permitted McCarthy to retain something of what she was seeing and feeling on site and use it as an aide-mémoire: “In the studio I use slides freely. The photographs I have taken on location stimulate me the way the original subject did…. As I look through the viewer… the whole world for me is the slide. I am able to imagine that I am there, seeing that view for the first time.” But photography could occasionally function beyond just acting as a memory prompt. Sometimes when stuck for an idea or an approach to how she wanted to paint a setting, McCarthy would play around with her slides:

In my mind I react as I would have done on the spot, looking for a feature to be the focus of my attention, observing what can be used as it is and what needs to be moved, or omitted, or changed in size. I may run twenty or thirty slides through the viewer before one gives me the jab in the solar plexus that I recognize as “an idea.” Something, a colour, a form, a movement, a pattern, or a mood, will suddenly make me want to paint, and I put that slide to one side. After a bit I go back over the ones I have set aside and decide which to use as my starter. Sometimes it is three different views of the same place that I work from. Occasionally I will put two slides into the viewer at once to see if the complexity of the confused images is more exciting than either by itself.

But ultimately, for McCarthy, even when photography played a greater role, it was still just a tool.

Nothing But Plein Air

Modern plein-air painting has its origins in the nineteenth century with the work of English painter John Constable (1776–1837). It was adapted by the Barbizon School in France, who introduced its use in America and to the Impressionists, in particular Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and Claude Monet (1840–1926). The latter is probably its most famous practitioner in recording the changing light and atmospheric conditions on his subjects. The plein-air tradition in Canadian art is an extension of these influences. The novel approach necessitated some important innovations such as the easel and pochade boxes that facilitated the practice.

Wendy Wacko’s 1983 documentary Doris McCarthy: Heart of a Painter highlights her friend’s “outdoor approach,” and, as McCarthy’s photographs attest, working in the elements was a central component of her practice. As McCarthy herself said: “When I’m working out of doors and the light is changing every minute, there’s a sense of excitement and pressure because you have to get it down, because in the afternoon the shadows are going to go in the other direction. So, you don’t waste any time. Spontaneity and speed are elements that can make a painting interesting.” The ways that the weather could impact the appearance of a scene sometimes influenced McCarthy’s choice of medium, as did the conditions under which she had to work. In general, she preferred oil in cold weather and acrylic and watercolour in hot climes.

Because her time on location was limited, McCarthy prioritized recording the intangibles—the colours, textures, space, and three-dimensional qualities of the forms. “Space is one of my obsessions,” she said, “and I usually find my inspiration by looking into the distance.” When she started a painting, she focused on composition, in part through the selection of what to paint, what portion of the landscape to frame, and some manipulating of forms as she carefully traced a path from the foreground to the background. Representing open space in landscape painting is challenging because linear perspective, originally developed in urban settings, lacks clear sightlines. McCarthy, however, always looked for a “feature to be the focus of my attention, observing what can be used as it is and what needs to be moved, or omitted, or changed in size.” In this search she sometimes used her photographs to find “an idea.”

Composition & Process

Throughout her career, McCarthy stressed the important role composition played in her painting. She told Canadian art historian and writer Joan Murray in 1983 that “if you don’t have a good composition, you may as well throw [the canvas] away because nothing is any better than its composition.” She thought that in Fisherman’s Shack, 1933, she first used a well-thought-out composition: “I was deliberately designing, echoing the movement of the nets in the roof-line.” It is a textbook treatment, much like the paintings of the Early Renaissance painter Giotto (1266/67–1337), who first mapped out compositional rules for naturalistic painting and who McCarthy would have referenced in her art history classes. The rows of garden greens pull the eye from the bottom of the canvas to the middle, where an open door invites us into the shack. The hanging nets carry our eye across the middle ground, with the poles drawing us to the sky. The sky then arcs downward on both sides, and the curving waves of the sea pull us back to the shack. McCarthy was disappointed when this important work got little critical attention when exhibited a year later in 1934.

As McCarthy’s work evolved, her use of compositional techniques became more subtle. Later, she favoured the term “design” over “composition.” “I gradually changed the word composition to the word design… to feel free to create and not just arrange what was in front of me…. Design means to me the relationship of everything in the painting to the story you are telling. You have to make up your mind before you start, what you want to say, and that becomes the focus. I’m very conscious of the edge of the canvas and that I must keep your eye active inside the frame and have a focal point on which it can rest.”

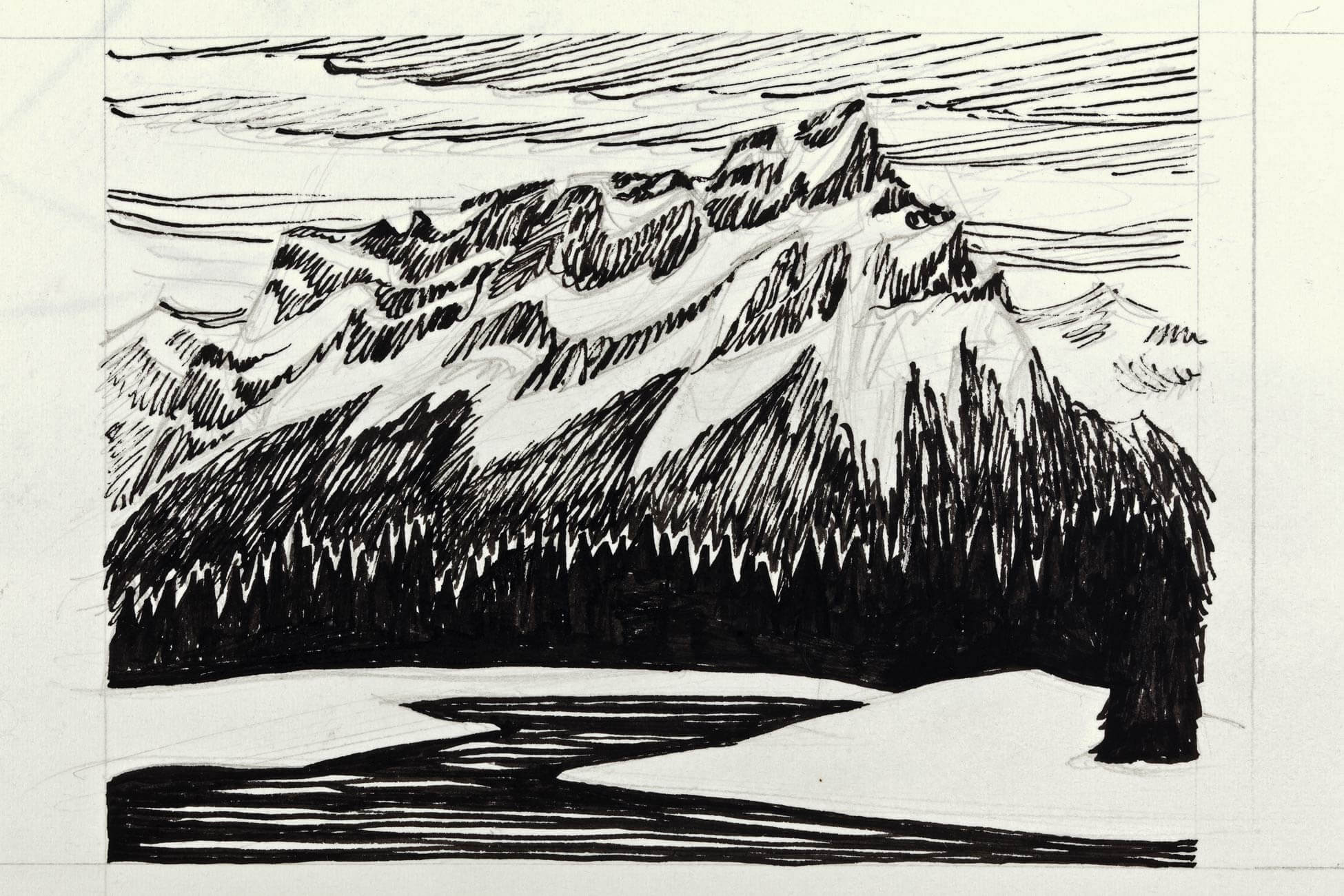

The importance of composition was complemented by strong drawing skills, a lesson McCarthy learned in 1935 at the Central School of Arts and Craft in London, England. There, John Skeaping (1901–1980) taught her to seek out the most telling line, the one that could encapsulate the movement of the object depicted. This advice must have resonated with her because it rephrased what Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) had told her as a student: “You think a think, and you draw a line around it.”

McCarthy’s approach to painting a finished work remained relatively consistent :

With thin colour, turps with just a hint of blue in it, I make three quick lines, enough to place the mass off centre, low enough to leave room for the far hills, high enough to allow some less eccentric snow shapes to take the eye upwards and inwards to the centre of interest. With bold light lines I establish the shore-line and the swinging movement of the distant mountains, and plot two or three shapes of foreground snow forms… Then I sit back and evaluate. Unless the shapes are already well balanced, rhythmic in their relationships, interesting, I should not go on with it. From the very first strokes the painting must have enough life to give some of its energy back to me, sustaining me through the whole process of development.

She then worked out the tone scheme, “establishing the dark areas and seeing how well the pattern of dark and light” told the story. McCarthy would then stand back to judge the composition before making her final revisions. Only then did she pick up her palette and begin to paint, starting with the most challenging and complex forms, her centre of interest, and the more complex colours. “Every brushstroke must describe the form by its direction and texture as well as by its tone and colour. I am always drawing in paint.” This goal is similar to that of French Fauve painters such as Matisse and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958), who said of his technique: “What I wanted to paint was the object itself with its weight, its density, as if I had represented it with the very material of which it was made.”

The Shadow of the Group of Seven

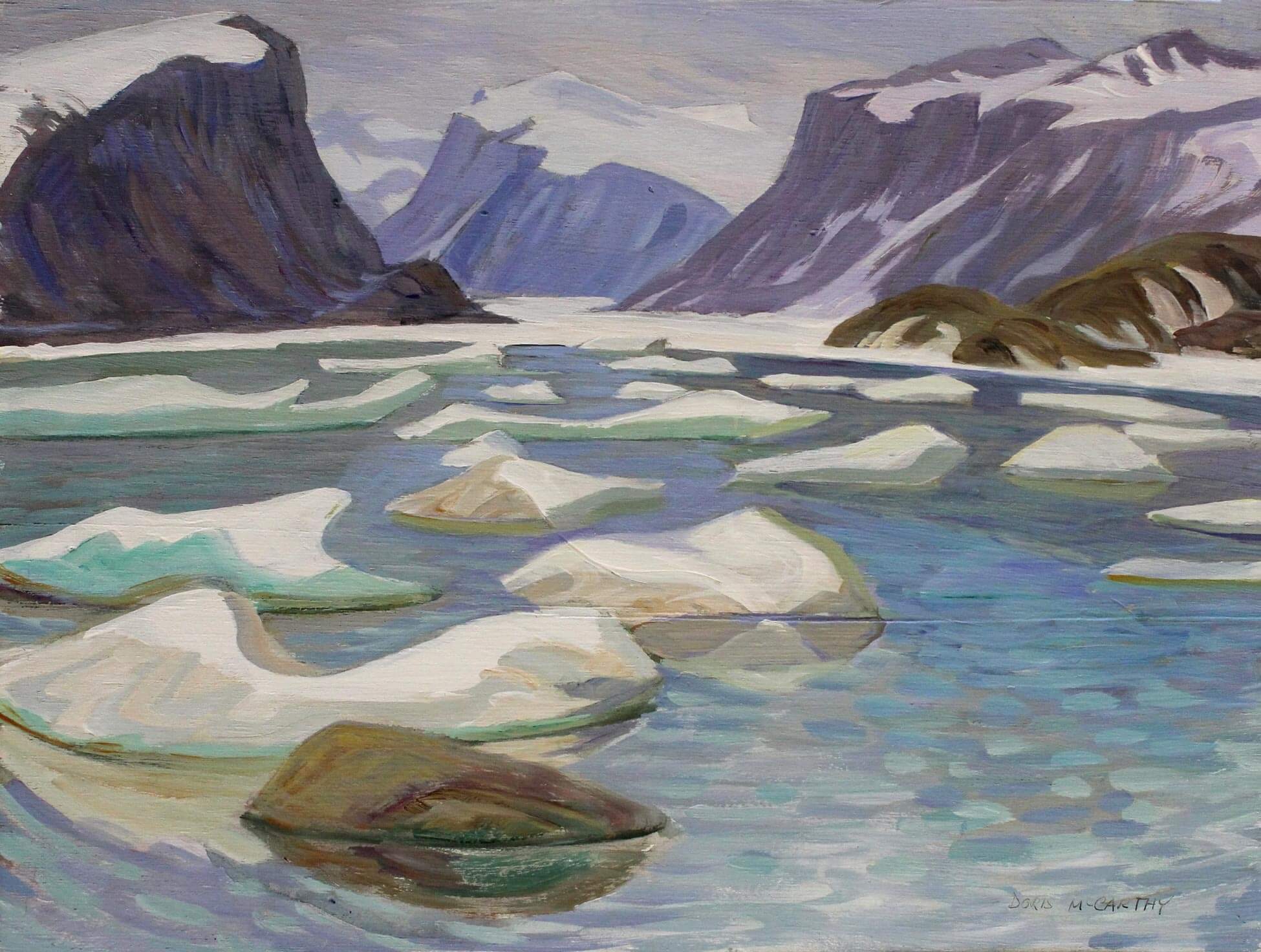

Though McCarthy acknowledged the importance of the Group of Seven in inspiring her goal to paint every region of Canada, she disliked comparisons that were made between her work and theirs, and, in particular, references that her Arctic paintings were similar to those of Lawren S. Harris. In truth, their styles could not have been more different. Harris’s depictions are more sculptural, with solid outlines delineating the various shapes as they echo each other—the snow-covered mountains resembling clouds, and the clouds looking like snowdrifts in the sky. This effect is tied to Harris’s transcendental spiritual and mystical beliefs. McCarthy’s images of the North, in contrast, convey a sense of warmth in a more intimate space. She gives greater attention to detail as she tries to capture the subtle variations of a scene—the textural qualities, transparency of the glaciers, and rich differences in colour. Even at their most abstract, McCarthy’s paintings are anchored in the actual scene.

When McCarthy was a student at the Ontario College of Art (OCA, now OCAD University), she visited Harris’s studio and, though impressed by the artist and his work, she found his paintings “bloodless” and “intellectual”: “Mine [are] less abstract, warmer and more loving.” She did, however, admire works by A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) and Arthur Lismer, who had taught her in Saturday morning classes at OCA. “He gave me faith in myself,” she said, and she also appreciated his approach to art and life. He inspired her to become “a great painter of Canada.”

McCarthy’s early pieces bear traces of the Group of Seven’s art, including the way she nestles her houses in urban and rural scenes and, like Jackson, captures the rhythm of the land. William Moore has noted a number of details that appear to be drawn from specific works by Jackson, Lismer, Harris, and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932). When asked about her early work and its style, McCarthy answered: “I would say Group of Sevenish…. I am naturally an outdoor person… so landscape was a natural choice. The Group of Seven were the people that were doing the creative and interesting work with landscapes, so… that’s where I started.” In another interview she was more precise: “My original influence was the Group of Seven…. I bought [their] philosophy, and I was thrilled by their work, and I certainly emulated them as a group.”

The Group of Seven essentially gave McCarthy licence to go “out into nature and [paint] what was there.” She was determined to remain faithful to her subject in a way that defined the style of each painting. The Group, in contrast, went out into nature, but each member forged his own individual style, particularly Harris. As artist John Scott observed while McCarthy was still alive, “McCarthy is the last living artist with a direct connection to the Group of Seven,” but, in forging her own distinct approach, her art can never be mistaken for a Group of Seven work.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements