Doris McCarthy is the only Canadian artist to paint every province and territory in Canada—a remarkable accomplishment that merited the Order of Canada in 1986. In her landscapes, she expressed her sense of adventure, her faith, and her love of the country. She also wore many hats over her long career, nurturing some of Canada’s most famous artists in her role as a teacher and constantly innovating through her published writings. Confronting sexism throughout her life, she courageously dedicated herself to each pursuit in an uncompromising way, and in recent years her remarkably varied body of work is being rediscovered and appreciated.

Educating Artists

-

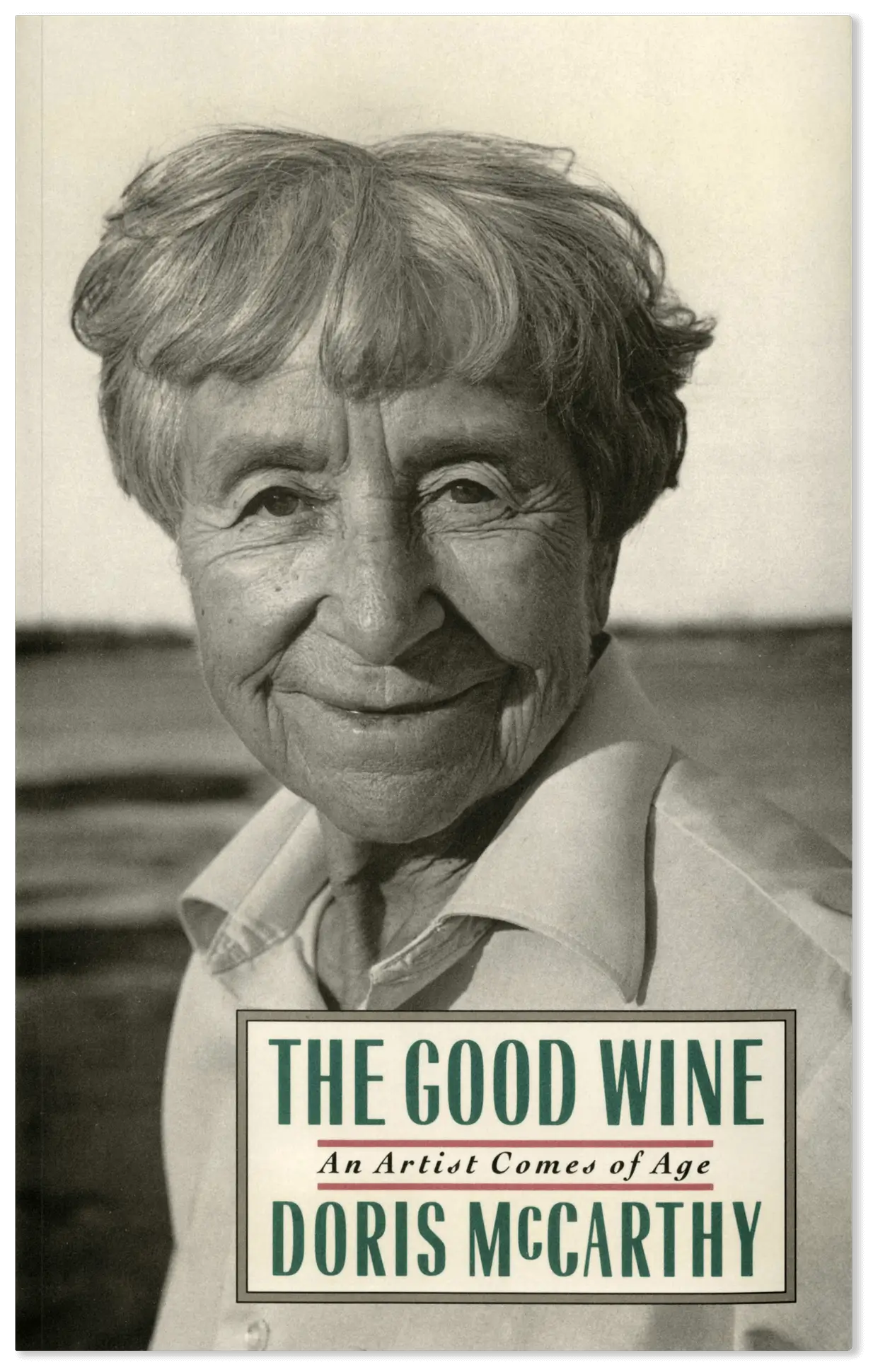

Portrait of Doris McCarthy

Photographer unknown

University of Toronto Scarborough Library -

Kazuo Nakamura, August, Morning Reflections, 1961

Oil on canvas, 93.7 x 121.5 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa -

Harold Klunder, Across the Sea Of Life (Cry of the World), 2002–4

Oil on canvas, 152.4 x 304.8 cm

Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec -

Tom Hodgson, Flowers, 1962

Watercolour and ink, 36.8 x 46.6 cm

The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa

In a 1999 article for the Toronto Star, McCarthy writes: “I taught Sunday school at 13 and found I had a natural talent. So at 21 I became an art teacher because it allowed me to eat and create.” In fact, where most artists take up teaching to supplement their art, it had always been McCarthy’s goal to be a teacher (initially as an English instructor and aspiring writer), and she remained in that profession for forty years at Central Technical School (Central Tech). As with everything she undertook, she did so with commitment.

McCarthy’s former students spoke of her as both an inspiration and a role model. They include Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002), Tom Hodgson (1924–2006) (both members of Painters Eleven), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), Jack Kuper (b.1932), Harold Klunder (b.1943), and Barry Oretsky (b.1946). Wieland described McCarthy as “the most exciting woman I’d ever met,” adding, “when she walked into the classroom… you could feel her warmth and kindness…. I worshipped the ground she walked on. She was the first Bohemian I ever met…. She was a very great teacher.” Oretsky recounted how McCarthy came into his class and critiqued the students’ work. They asked what she thought of Oretsky’s piece. She responded, “He’s an artist… and you’re students.” She explained that Oretsky was willing to experiment, fail, and try again, “because he wants it that bad.” Later, she nominated him to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Kuper, an orphaned European war refugee, arrived in Canada in 1947 and, when he wanted to take art classes, McCarthy lobbied to get him into the art department at Central Tech and fought to get him financial support. “I often think of Doris McCarthy with gratitude and the highest esteem,” he said, “and wonder what direction my life would have taken without her.”

McCarthy’s approach to teaching likely adopted elements she absorbed from her own instructors and colleagues. Initially, like her former teacher Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), she focused on nurturing creativity rather than technical skills. From John Dewey (1859–1952) she adopted his “project method of education… where the students pick their own goals… organize themselves… [and] evaluate the work,” just as she had experienced in her teens when she joined the Canadian Girls in Training.

Most of the students McCarthy taught in her first decade were in vocational training programs where art was only an elective course. She no doubt had to modify her progressive approaches in favour of a more conventional pedagogy. She may have been spurred on by what she learned at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, England, while on leave in 1935 and 1936, where it became obvious that her training at the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University) fell short on fundamentals.

Few have written about McCarthy’s pedagogy beyond the fact that she focused on the foundational elements of artmaking. She echoed the Bauhaus model of teaching favoured by her department head Peter Haworth (1889–1986), with its emphasis on experimentation in various media while simultaneously teaching basic principles of form and colour. As she later said to Klunder: “We considered technique as grammar. You need to know it in order to talk. You never think about grammar when you are talking, but you use it. I never think about perspective when I’m working, but I’m using it all the time.” In the words of art historian and writer Jann Haynes Gilmore: “McCarthy taught composition, design, and other disciplines, always experimenting, deducting, and simplifying her subject…. Her methods were engaging and stimulating for the vocational ‘toughies’ (her words) that she taught.”

During the Second World War, when many of her male colleagues at Central Tech had enlisted, McCarthy had the opportunity to teach senior painting classes—and she made the most of it. As she wrote in her autobiography:

I began to give assignments that would make them explore some currently fashionable ways of working… to create a painting using only two flat colours… [or] to produce a good piece of “found art”…. I showed the class a film of Karel Appel, the Dutch abstract-expressionist master, in which he filled a spatula with heavy paint and ran the length of his studio to gain momentum for the slashing stroke he made with it on the canvas. We moved outside to the playing-field [where] the students flung paint around by the big brushful and let the drips run where they would…. Because I wanted them to learn to evaluate their own work, my criticisms were usually Socratic…. To develop my own discrimination I myself began to work in flat colour with hard edges, to eliminate detail and tell my story in the simplest form possible. I found this challenging and exciting.

McCarthy was disappointed at war’s end to be reassigned to junior classes, but she continued to learn about contemporary art in order to stay up to date with the newest trends. She took a sabbatical from 1961 to 1962 to travel around the world and develop her slide collection for art history classes, gaining remarkable insight into the worlds of art beyond the Canadian context.

Portraits of a Nation

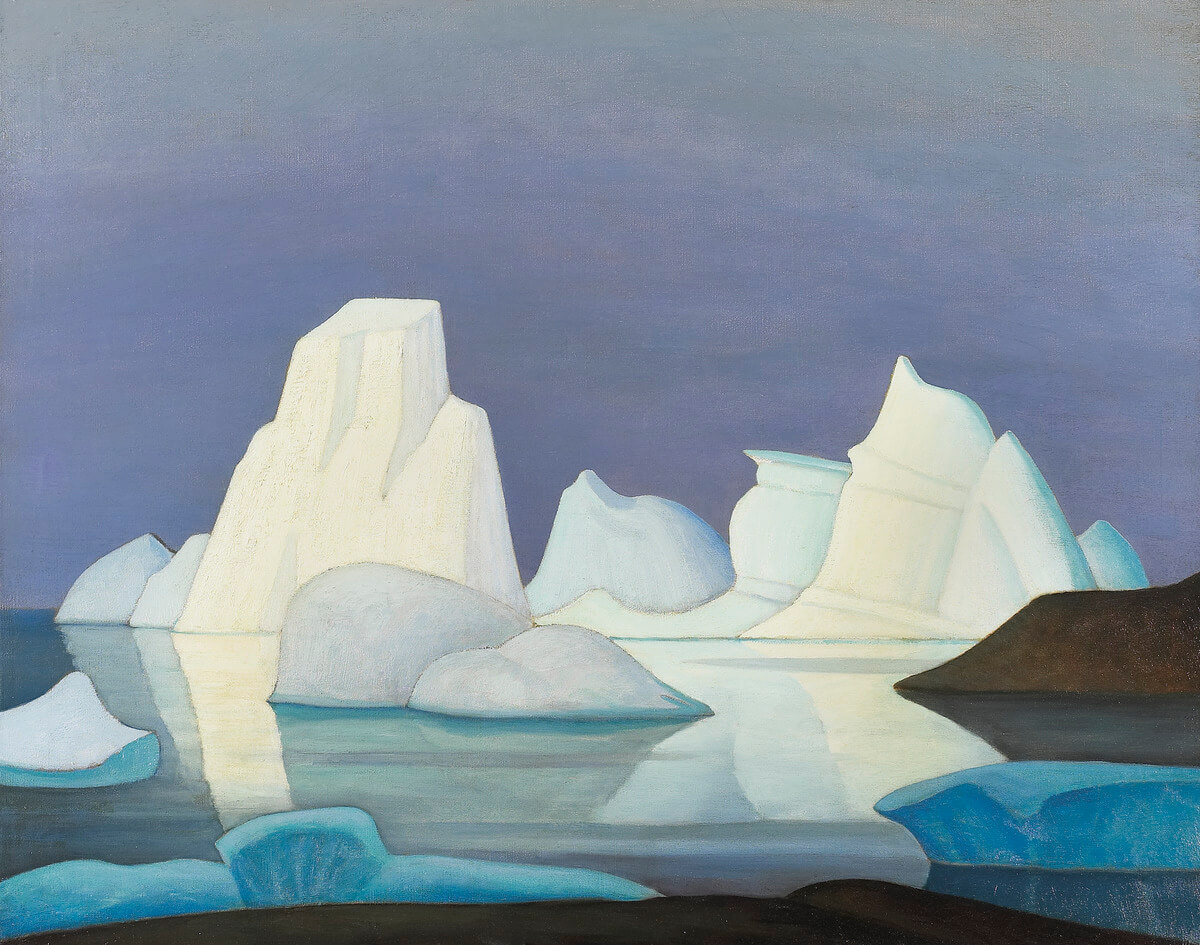

In Wendy Wacko’s 1983 documentary Doris McCarthy: Heart of a Painter, McCarthy states: “I want to paint Canada.” McCarthy went on to visit and paint in every province and territory, especially after she retired from teaching in 1972. Her longer journeys took her overseas, most often to England, but also around the world during her 1961 to 1962 sabbatical year.

McCarthy credits the Group of Seven for inspiring her goal of painting the whole of the country. The specific prod appears to have been her first trip to the Arctic (Northwest Territories), prompted by her younger Central Technical School colleague Barbara Greene (1917–2008) in the summer of 1972. The paintings from this region soon triggered invitations to visit other areas of the country—Alberta and Prince Edward Island in 1974, Newfoundland and British Columbia in 1975, the Yukon in 1976, Manitoba and Saskatchewan in 1982, and Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in 1986—with frequent returns.

McCarthy’s liking for travel, her love of the great outdoors, and her painting style made her ideally suited to become a visual chronicler of Canada. She adapted her style to the scenes she depicted so they reflected the “look” of a place as well as its character: “Painting demands a concentration and sensibility that grows into an intimacy with the country, greatly intensifying your awareness of it.” With over 5,000 works, McCarthy was able to achieve in a single person the goal of the Group of Seven and its successor the Canadian Group of Painters, to paint the whole of Canada—an achievement no other single artist has accomplished. It is fitting that she was awarded the Order of Canada in 1986 as the great painter of the Canadian landscape.

The Divine in Landscape

McCarthy was a devout Christian, and her early years were punctuated by her participation in various religious groups. She regretted that her art friends never showed any affinity for religion, so the only way she could bring both interests together was through her love of the natural world.

McCarthy produced a number of religious pieces, including a carved nativity scene for the Church of St. Aidan and several church banners representing biblical scenes. She also featured the angel in the weather vane on her home, Fool’s Paradise, in some of her works, such as Home, 1964. Here, the image is flattened with its extreme bird’s-eye view, an angle that may represent God or an angel looking over McCarthy’s dwelling. The treatment echoes the religious paintings of early Renaissance masters, in particular Giotto (1266/67–1337), whose work she taught, and modern artists such as Carlo Carrà (1881–1966), who revived the style.

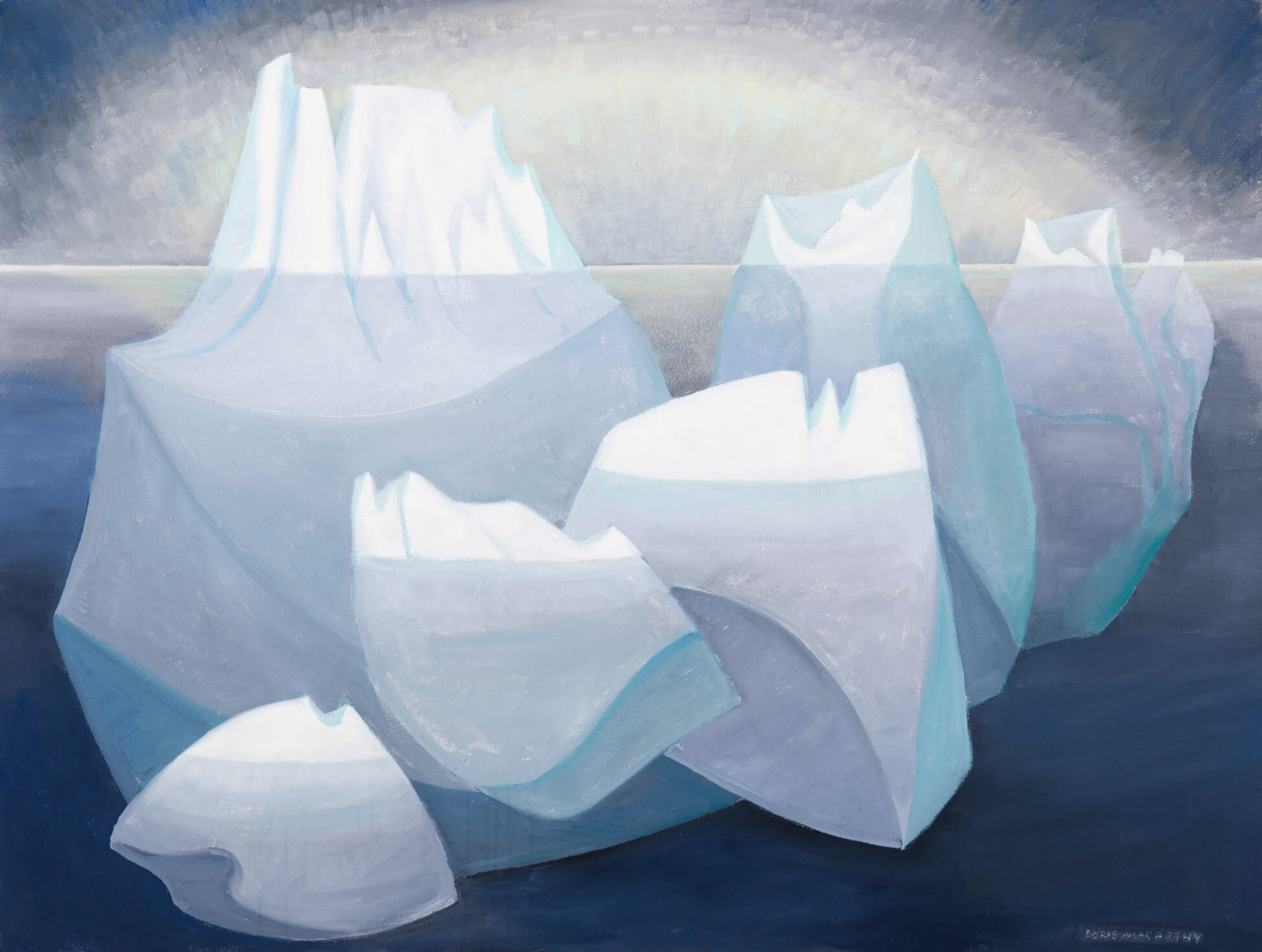

Though McCarthy’s landscapes do not speak directly of religion or the divine, they reveal a love for the land and a degree of intimacy with it. In one interview, she spoke of wanting “to get to know mountains as individuals.” In the 1983 documentary Doris McCarthy: Heart of a Painter by Wendy Wacko, she expresses her frustration at having her Arctic paintings compared to those of Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970): “I know what they mean—we both paint the Arctic, [but] I’m romantic and I see God in nature.” She was not expressing pantheism, but, as she wrote in her autobiography: “The mystery of creation convinced me that God was immanent as well as transcendent in the rocks, the trees, the animals and me—still creating but not exercising the authority I had once believed.”

McCarthy’s relationship with the divine comes not only in admiring nature but in revealing the hand of God in its creation: “Nature is without moral quality. It just is. I want to offer you nature with meaning and purpose and love in it. The Kingdom of God, in my mind, involves beauty and order. I try to create that in a painting with coherence and unity.” In other words, the act of painting is one of re-creation where the artist echoes the divine. The artist is a microcosm of the macrocosm: “I saw God (revealed) in nature and God was real to me.” Elsewhere, she notes that her art “is an expression of my belief in the unity of all creation and creation’s unity with the Creator.”

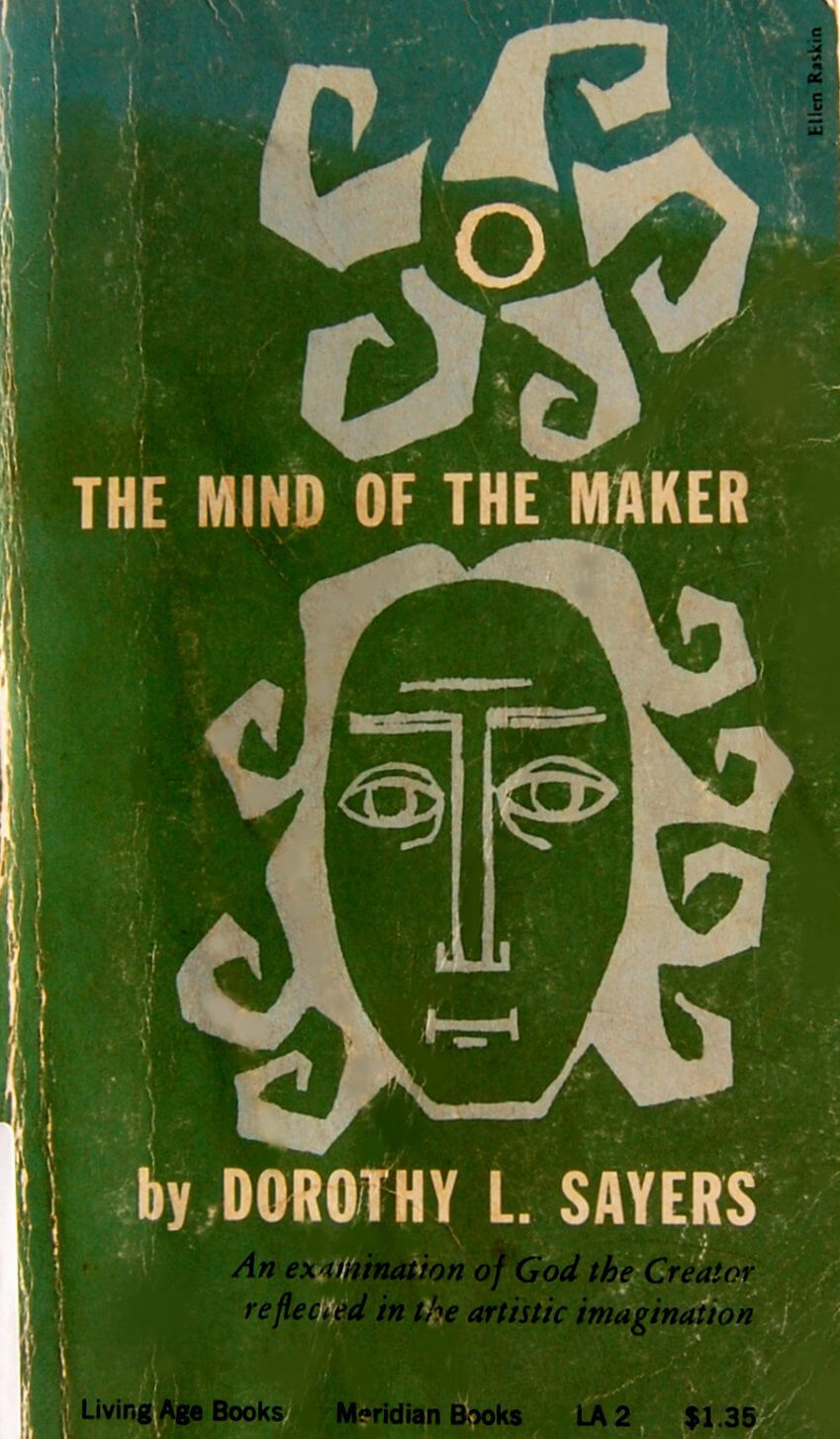

In many ways, McCarthy was following a tradition famously expressed during the height of the Gothic period in European art history (12th–14th centuries), where the creative act was seen as a re-enactment of the divine act of the creation of the universe. It was expressed in the construction of Gothic cathedrals and in images showing God holding an architects’ compass. Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), an author McCarthy loved and met, rephrased this idea in The Mind of the Maker (1941), where the creative process functions in a dynamic relationship with the Trinity.

The Artist as a Writer

McCarthy decided early in life to be a writer. As a teenager, she felt that although “drawing and painting came naturally to me, there were two other girls at school who could draw ladies better than I could.” She also saw something sibylline about art: “I didn’t think ordinary people got to be artists. I expected to be a writer, which didn’t seem quite so mysterious or hard to achieve.” She wrote in her autobiography: “Although I chose the art option at high school, nothing at Malvern nourished my talent or my interest…. The courses in English and the teachers were inspiring, and my marks in literature and composition were high. Writing seemed a possible career, and university a route that could lead me in that direction.”

Circumstances, however, made the choice for her. She graduated from high school at the age of fifteen but was not eligible to enter university for another year. Then, after attending Saturday morning art classes at the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University) during her school years, she was awarded a full-time scholarship to the college.

McCarthy was happy with the change in plans, but her interest in writing and English literature never left her. Describing her abstract hard-edge landscapes, such as Banner #2, she writes: “The OSA [Ontario Society of Artists] eased off in the summer and let me escape to Georgian Bay…, where I tried to say the rocks and water movements in the simplest way possible.” Later, in New Zealand in 1961, she regained confidence by goading herself to “tell” the scene rather than imitating it. It seems that whenever she needed inspiration, she drew on the writer within her.

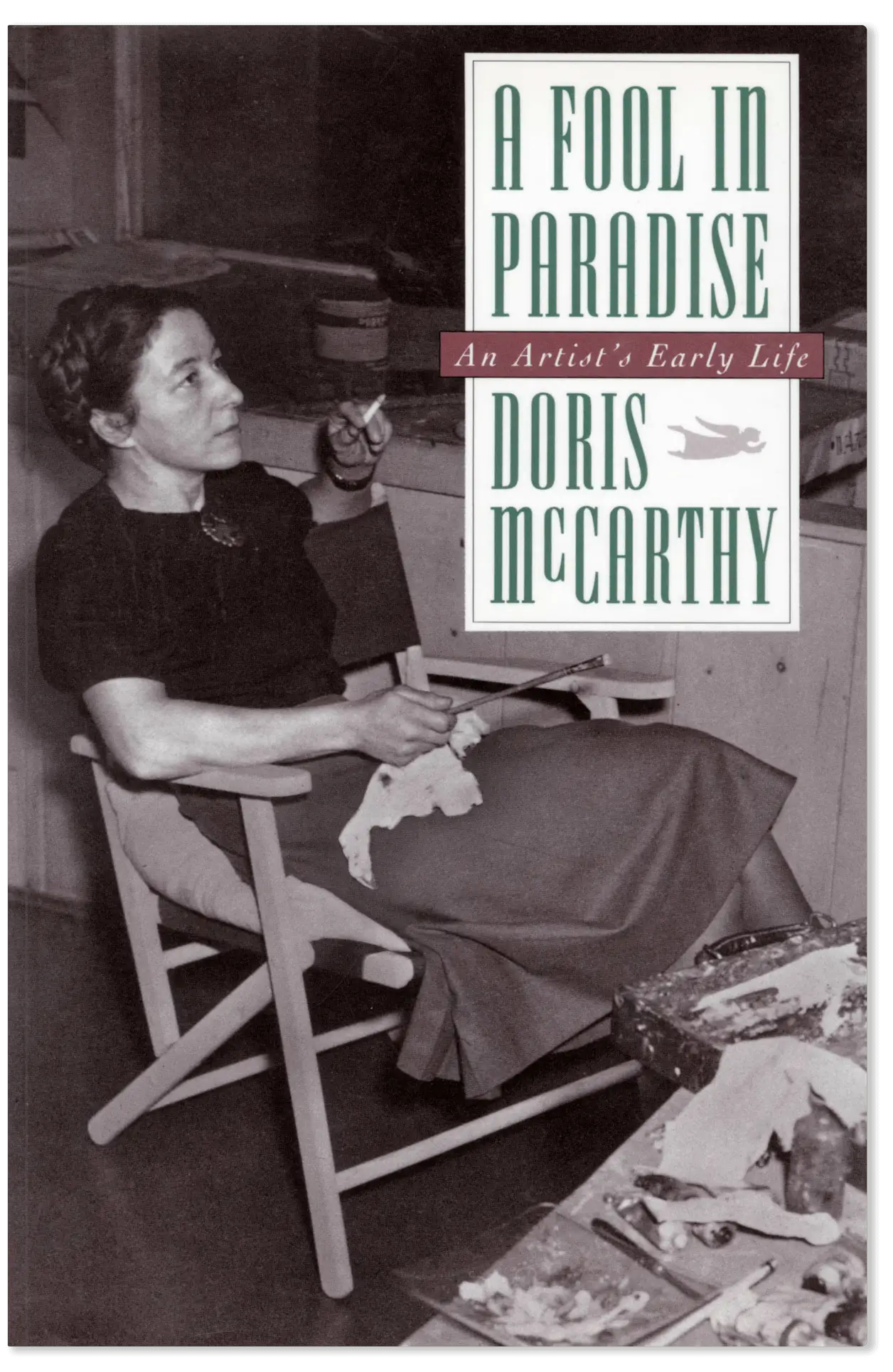

McCarthy enrolled in English literature classes at the University of Toronto soon after she retired from teaching at the Central Technical School. One of her instructors was the noted literary critic Northrop Frye (1912–1991). In 1987, as one of her final courses to complete a BA Honours in English Literature, she registered in creative writing. She began writing her life story, resulting in the publication of A Fool in Paradise: An Artist’s Early Life (1990), The Good Wine: An Artist Comes of Age (1991), and Doris McCarthy: Ninety Years Wise (2004). A fourth book appeared in 2006, Doris McCarthy: My Life, composed of parts from her first two books with one new chapter.

A Fool in Paradise was well received by critics. Elspeth Cameron described the book as “so direct and simple it seems almost to invent its own form,” adding, “she has produced a unique and valuable literary work that could become a model for others.” In this way, McCarthy’s writing echoes her visual output. As is common with artists, however, she wrote little about her art, teaching, or practice.

The autobiographies gave McCarthy the opportunity to take stock of her long life. She was turning eighty when the first volume appeared. She had the tools on hand because she had always kept her letters and journals. Moreover, she had a big personality and she liked to be in control. An autobiography is an excellent way to control the narrative of one’s life.

Confronting Sexism

When McCarthy got her job at Central Technical School (Central Tech) in 1931, she took over from a teacher who had to resign because she was getting married. Yet, as she told art critic Sarah Milroy, “I was fortunate in that there was very little sexism in the art department at Central Tech”—except “in terms of promotion… but I just didn’t care.” She taught junior grades at the school until the outbreak of the Second World War, when her male colleagues enlisted, and, although she relished working with senior students, she was again demoted when the men returned after the war. Similarly, she was initially denied membership in the Ontario Society of Artists because she was a woman.

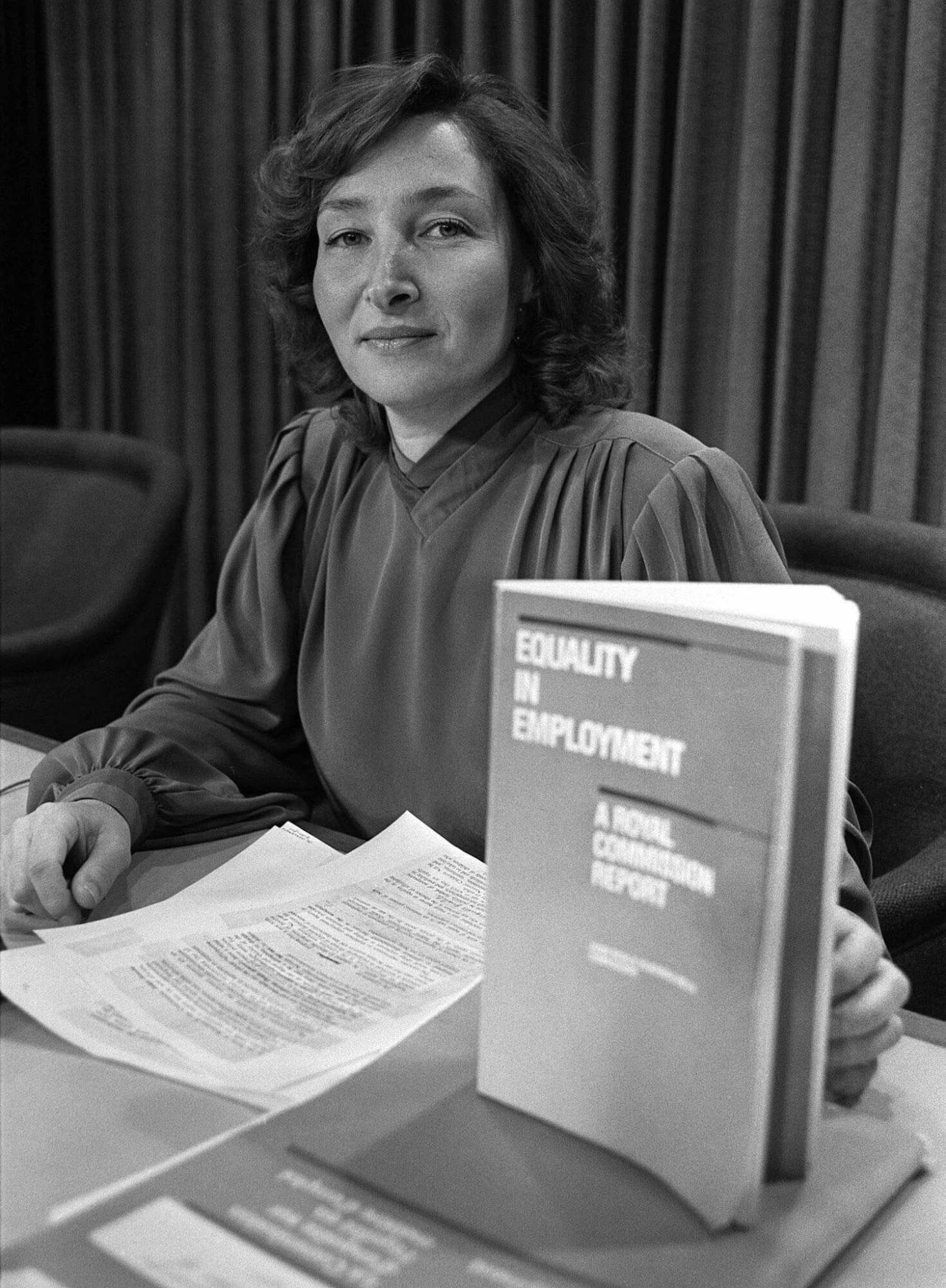

It was not until the 1960s and early 1970s that substantial changes would be made to better accommodate women in the workplace, with statutory maternity leave and rules against discrimination on the basis of sex or marital status in hiring, firing, training, and promotion. The very term “employment equity” only came into existence in the 1980s, with the publication of Rosie Silberman Abella’s book Equality in Employment, published in 1984. These reforms came too late for McCarthy.

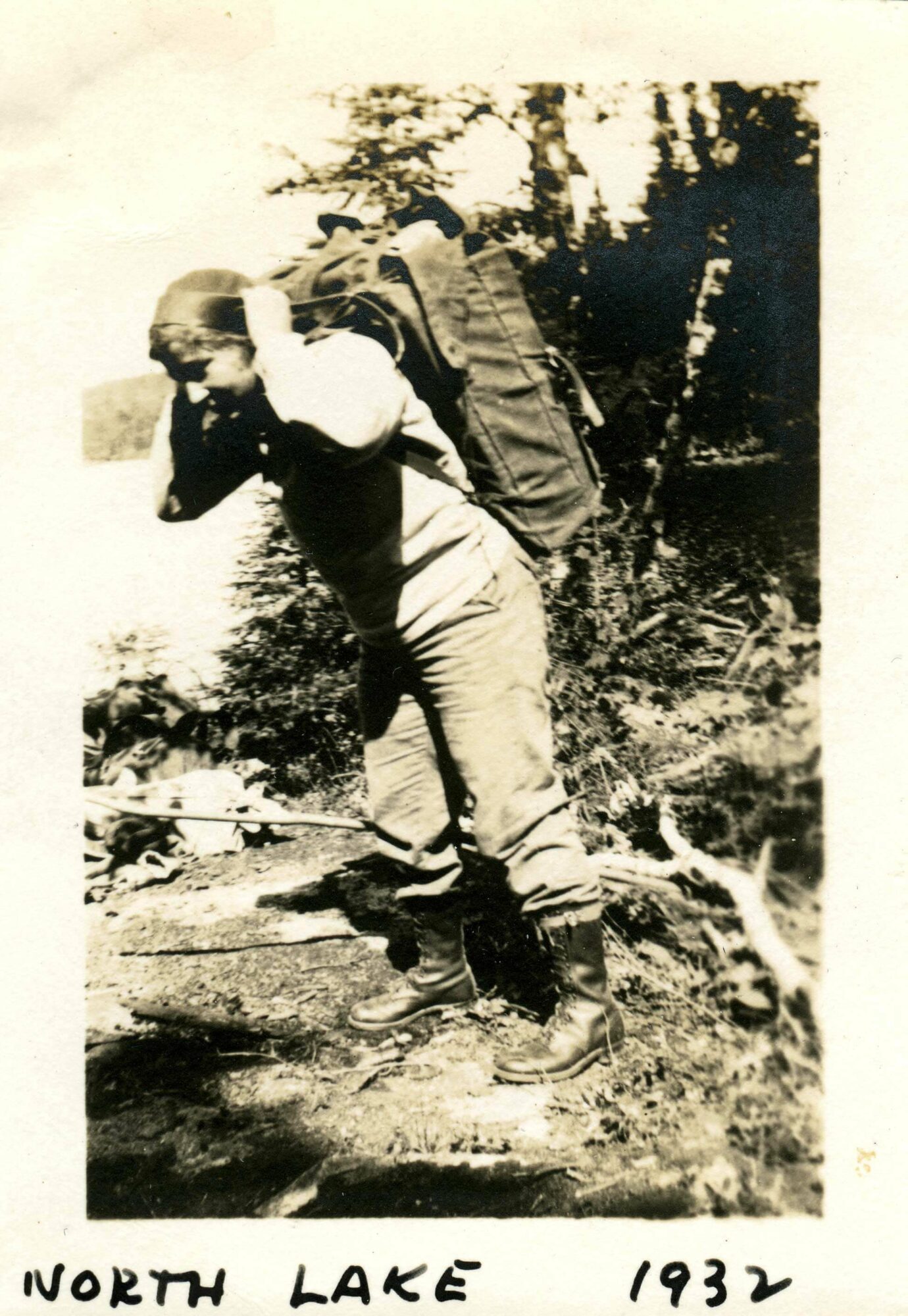

Nevertheless, McCarthy seems to have developed an independence and blasé attitude about sexism in her early years. Her father imbued her with a passion for the outdoors, which meant she had to be self-reliant and resourceful. She told writer Susan Crean that “my family was not patriarchal and I didn’t grow up feeling defensive about being a girl.” She lived life with the attitude that there was no time to waste: Wendy Wacko, who documented McCarthy’s life in film, noted: “She thought the best approach was to do the best job you can and don’t waste time whining about it.”

Recognition & Legacy

McCarthy may not have been a feminist fighting the inequality she encountered, but her stubborn independence and self-reliance made her a modern woman artist who forged ahead in getting what she wanted without dwelling on the roadblocks she encountered. Her approach became a model for many of the young women artists who were taught by her—such as Joyce Wieland.

The greatest injustice toward McCarthy may be the lack of recognition by Canadian art institutions. As The Globe and Mail arts reporter James Adams noted in 2010, the year McCarthy died, she had been omitted from a recent survey of twentieth-century Canadian art, and The Canadian Encyclopedia had no entry on her. To this day, the National Gallery of Canada has only two of her oils and four watercolours in its permanent collection; the institution’s former Curator of Canadian Art, Charles Hill, explained: “I don’t think she’s contributed anything original that’s enduring.” The McMichael Canadian Art Collection has only one large McCarthy oil painting, and the Art Gallery of Ontario has one oil and one watercolour.

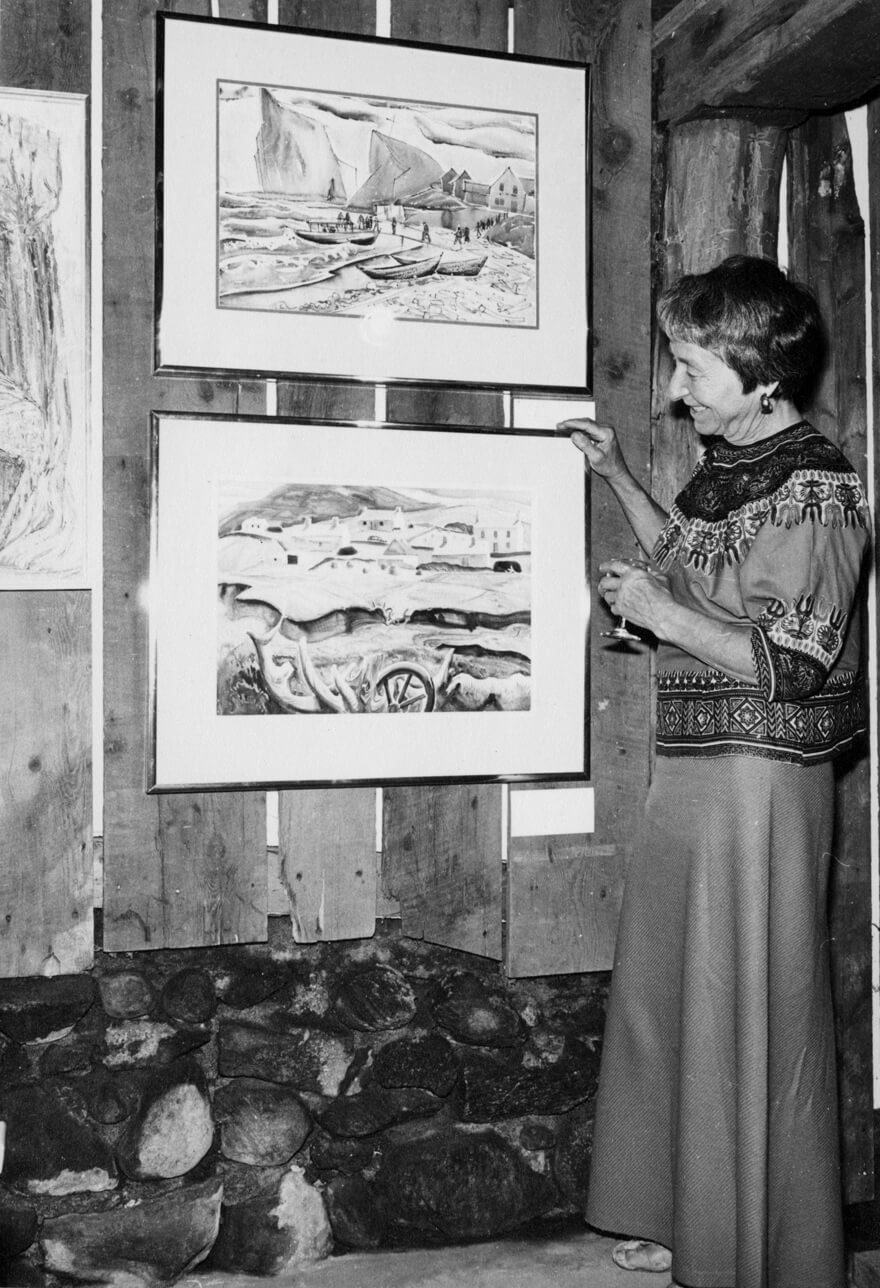

In spite of the poor opinion of McCarthy’s work by heads of major art institutions, such as Hill, McCarthy’s star has been rising, as has those of many of her friends, including Yvonne McKague Housser (1897–1996) and Bobs Cogill Haworth (1900–1988). The major retrospectives at the end of the 1990s have given way to a series of exhibitions that occurred shortly after McCarthy’s passing. In 2010, Nancy Campbell curated an exhibition of McCarthy’s work at the Doris McCarthy Gallery, writing in her curatorial essay that “Throughout her decades of experimentation and adventure, always fearlessly roughing it in the bush, [McCarthy] has created a place for herself as an artistic pioneer, and as one of Canada’s most precious interpreters of the Canadian landscape.” In 2012, the Michael Gibson Gallery hosted Doris McCarthy: Selected Works 1963–2005, describing her as “one of Canada’s leading female artists who is recognized as one of the most cherished interpreters of the Canadian landscape.” More recently, in 2019, the McLaren Art Centre presented The Clean Shape, an important group show of the work of McCarthy, Rita Letendre (1928–2021), and Janet Jones (b.1952), portraying them as pioneers of Canadian abstraction.

As historical and critical attention on women artists in Canada has grown, McCarthy has emerged as a force among her peers. Her longevity, tenaciousness, dedicated friends and followers, and relative disregard for conforming to current trends have allowed her to survive in a world that, up to now, has not looked kindly on the accomplishments of women artists.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements