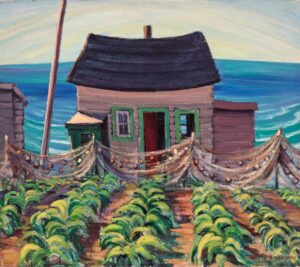

St. Aidan Banner c.1957

Doris McCarthy, St. Aidan Banner, c.1957

Unknown media, 274.3 x 91.4 cm

Church of St. Aidan, Toronto

McCarthy’s banner depicts Saint Aidan (d.651 CE), the seventh-century Irish monk who was the founder and first bishop of the Lindisfarne monastery and church on the northeast coast of England. He is presented in a frontal, iconic pose, wearing a decorated vestment. Saint Aidan holds a sceptre topped by a Gaelic Cross in his right hand and a model of a church in the other, presumably that of Lindisfarne Priory. At his feet, which are bare, is his name, and below that on the left is King Oswine (d.651 CE); in the centre, an illustration of a horse, a gift from the King that Saint Aidan gave to a beggar. Above Saint Aidan are two pairs of hands, one large and the other small—perhaps the hands of God holding Saint Aidan’s, or the hands of Saint Aidan holding those of his converted followers. On each side are five fish, probably symbolizing that Lindisfarne was an island. The circular shape in the upper centre could represent that island, with the fish suggesting the surrounding waters. In 1958, McCarthy visited Lindisfarne and painted on and around the Holy Island.

McCarthy’s relationship to her faith was a profound one. She was a devout parishioner of the Church of St. Aidan in the Beaches neighbourhood of Toronto practically all her life, from Sunday school on. At the age of eleven, she and her friend Marjorie Beer (1909–1974) wrote a play that was performed there, and her Canadian Girls in Training group frequently met there, too. During the Second World War, McCarthy carved a Christmas crèche and directed a number of the holiday nativity plays.

The St. Aidan Banner was one of two banners McCarthy made for the chancel of the church in 1956 and 1957 in honour of its fiftieth anniversary. They were hung for the celebration but soon were taken down, with no explanation. McCarthy was not happy and withdrew from participating until Beer’s death in 1974.

McCarthy organized a group production of banners in honour of her friend for Beer’s church, the Metropolitan United Church in downtown Toronto. Their success inspired McCarthy to continue: “Marjorie’s banners were the beginning for me of a series of liturgical wall-hangings.”

The style of the banner has a folklike quality, recalling the figures in her first public project in 1932—the murals for the children’s reading room at the Earlscourt Branch of the Toronto Public Library. What is surprising about the St. Aidan Banner are its departures from conventional iconography. Traditionally, Saint Aidan is never shown with bare feet, but McCarthy may have used this to represent humility before God. Saint Aidan is usually shown holding a Bible, or a torch to lead followers out of darkness. The torch could also be a reference to the saint’s name: in Gaelic, Aidan is a gender-neutral name that means “little fire.” Holding a church is a common image for bishops who order a building’s construction, as Saint Aidan did, and McCarthy may have been inspired by her 1951 visit to the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, where a mosaic shows Saint Ecclesius (d.532 CE) presenting the church to an enthroned Christ. The staff crowned by a Gaelic Cross is also rare in Saint Aidan iconography, as he is usually shown with a shepherd’s crook. The hands and fish have no precedent either, although the hands may reference one of Saint Aidan’s miracles when he beseeched God to save the city of Bamburgh from the ravages of King Penda of Mercia (c.606–655 CE).

The poetic licence McCarthy took for her image of Saint Aidan is likely the result of a lack of accessible information about his iconography. In the early 1970s, he was overshadowed by the more famous bishop of Lindisfarne, Saint Cuthbert. As such, McCarthy’s interpretation deserves great credit.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements