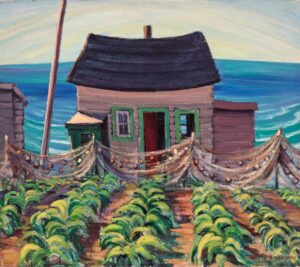

Kitchen of the Knothole 1959

Doris McCarthy, Kitchen of the Knothole, 1959

Oil on board, 40.6 x 30.4 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

This rendering offers a cropped view of a rustic cottage kitchen with a counter on the left, dishcloths hanging near the rear wall, and a stovepipe snaking its way to the pitched ceiling, framing what appear to be shelves or a three-paned opening to another room. A basket of fruit sits on the cabinet in front of the stovepipe, and a folding camp chair dominates the foreground. McCarthy painted this image in one of the two cottages on Georgian Bay she purchased with four friends in 1959. The largest cottage, known as the Keyhole, was named after a nearby inlet, while the smaller one, which McCarthy shared with artist Virginia Luz (1911–2005), was christened the Knothole “because it is not the Keyhole.” McCarthy had spent summers in this region since her childhood, and she loved it.

Kitchen of the Knothole is one of the few interiors McCarthy painted. She may have found them challenging—this image looks hurried and unfinished, and the space is difficult to read. In another similar work, Woodstove in Wardens Cabin, Revelstoke, B.C., 1957, the relative sizes of the objects depicted seem disproportionate: most noticeably, the shoes under the stove appear oversized compared to the pans resting on it. In Kitchen at Fool’s Paradise, 1954, she adopts a close-up view while depicting the objects in a cartoonish manner. Obviously, as an outdoors person, McCarthy was not captivated by interiors.

Despite its apparent shortcomings, Kitchen of the Knothole is a visually engaging work, drawing the eye across the surface through its use of line while punctuating the space with swathes of ochre, teal, and green. The lack of finish may be symptomatic of McCarthy’s transition to the abstract landscapes of the 1960s—such as Rhythms of Georgian Bay, 1966. It may also have been a product of her exposure to gestural abstraction in Toronto, highlighted by Painters Eleven and the massive influence of Abstract Expressionism: “I did a certain amount of Abstract Expressionism and gesture painting… but I didn’t take it seriously.” McCarthy, who had been a teaching assistant to Hortense Gordon (1886–1961), had also taught two members of Painters Eleven, Tom Hodgson (1924–2006) and Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002). “It was a great thing to see a group that were doing this interesting work,” she said, “and we had a lot of their work in the [Ontario] Society [of Artists] shows.”

McCarthy noted that, as a teacher, it was important for her to know the latest contemporary art trends: “There was always the pressure to keep up with art studies when I was teaching…. I felt that my own work should be reasonably contemporary and I tried all the new movements. I had to teach action painting. I knew how to do hard-edge and Pop. I had to discover what made them tick as art movements. They were valid periods, a challenge, and they broadened my own art appreciation.”

The late 1950s and 1960s marked a period of radical experimentation in the art world, ranging from performance pieces to Pop art to the text-based works of Conceptual art. One of McCarthy’s most famous students, Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), was becoming a major player in this newly revitalized art scene.

Kitchen of the Knothole was purchased by the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2019—the only painting by McCarthy in the collection. Bafflingly, all the major Canadian art institutions have largely ignored her work.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements