Doris Jean McCarthy (1910–2010) had a long and successful career as an artist, teacher, and writer. She is one of Canada’s pre-eminent landscape painters and the only one who worked in every part of the country. Her love of nature and attention to detail enabled her to capture the character of each region she visited. Though trained in the shadow of the Group of Seven, she soon forged her own distinctive approach as an artist. McCarthy proved to be an inspiring and devoted educator whose students included Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) and members of Painters Eleven. Her passion for writing resulted in three autobiographical volumes.

Early Years

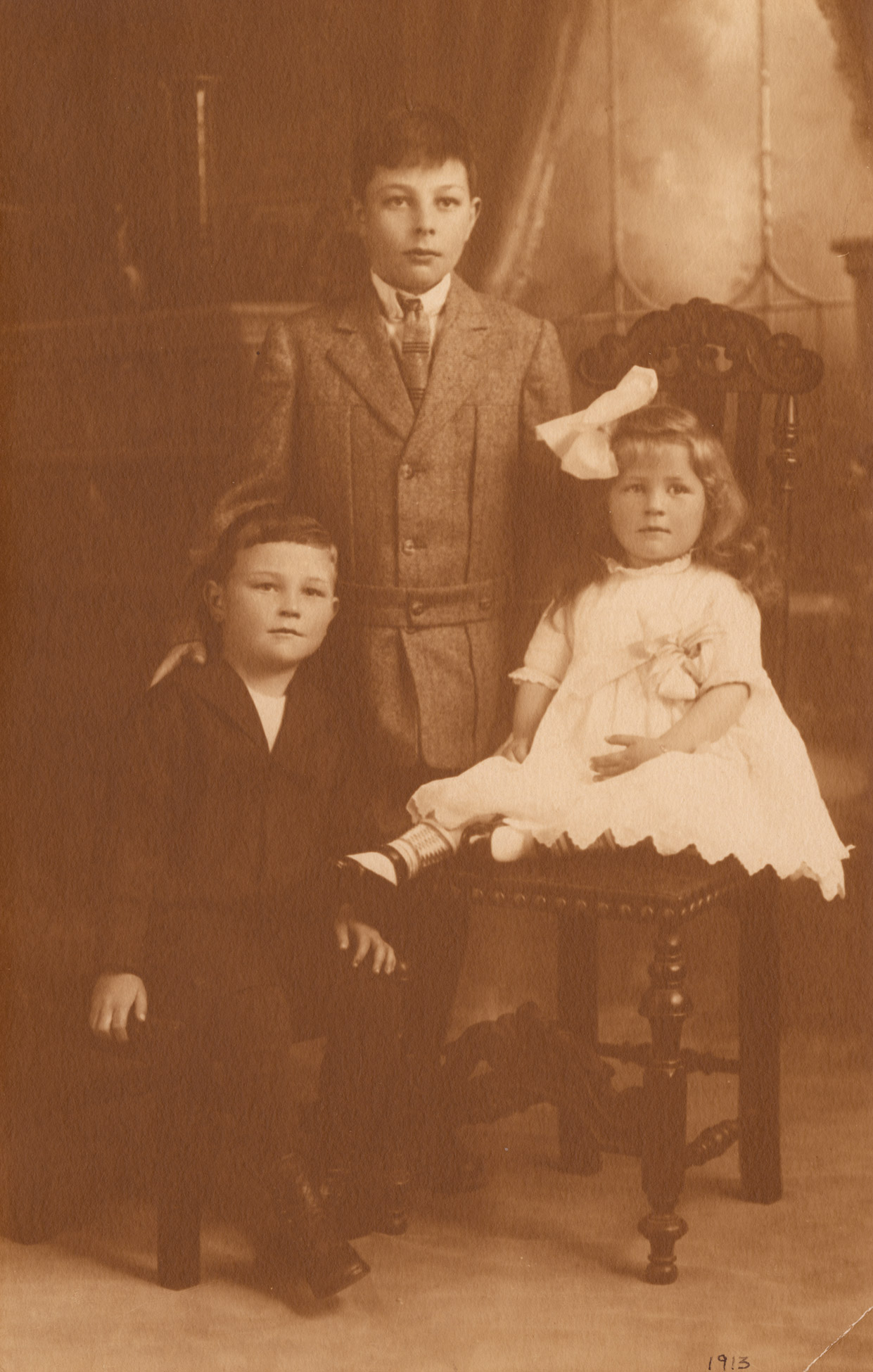

Doris McCarthy’s childhood was quite ordinary, though the family moved frequently at first. Her father, George Arnold McCarthy, met Mary Jane Colson Moffatt, a promising singer, while he was studying civil engineering at McGill University in Montreal. They married in 1901 and moved to Niagara Falls, where Kenneth was born the following year. In 1907, the family welcomed Douglas in North Bay, and, finally, in 1910, Doris Jean arrived in Calgary on July 7. Over the next three years, the McCarthys lived in Vancouver, Boise (Idaho), Berkeley (California), and then Moncton. There, they decided that the lucrative life of contract work was straining the family, and in the fall of 1913 George McCarthy became a city engineer in Toronto, in charge of railways and bridges.

The first three years of McCarthy’s life left her with an indelible urge to keep moving, both mentally and physically. Everyone she met recognized her energy and insatiable desire to travel. Her father imbued her with a love of nature—a fervour that found its way into her art. The family spent the summers renting cottages on Lake Ontario or the lakes north of Toronto: “Dad had conditioned me to feel that nature and the out-of-doors were an important part of my heritage.” In 1926, George bought a cottage near Beaumaris on Lake Muskoka. It was in rough shape, but father and daughter set to work shingling the roof and making repairs. These manual skills came in handy later, when McCarthy bought her own property on the Scarborough Bluffs and almost singlehandedly built her home there.

McCarthy’s relationship with her mother was strained, particularly in relation to how women should behave and live. Although McCarthy inherited her mother’s stubbornness, she remained devoted and loyal to her: “I think she looked back wistfully… at the opportunity she had missed, and I’m sure that was one of the reasons she supported me in every effort… to become an artist.” Like her mother, she was also deeply religious.

When she was eight, McCarthy met Marjorie Beer (1909–1974) and, as they nurtured each other’s literary ambitions, they became inseparable friends for life. Though McCarthy showed an interest in art and studied it in high school, she initially envisioned pursuing a career as either an author or a teacher: “Marjorie was already writing and being published in the ‘Young Canada’ page of the Globe. She and I were confident that we would be Canada’s next L.M. Montgomerys.”

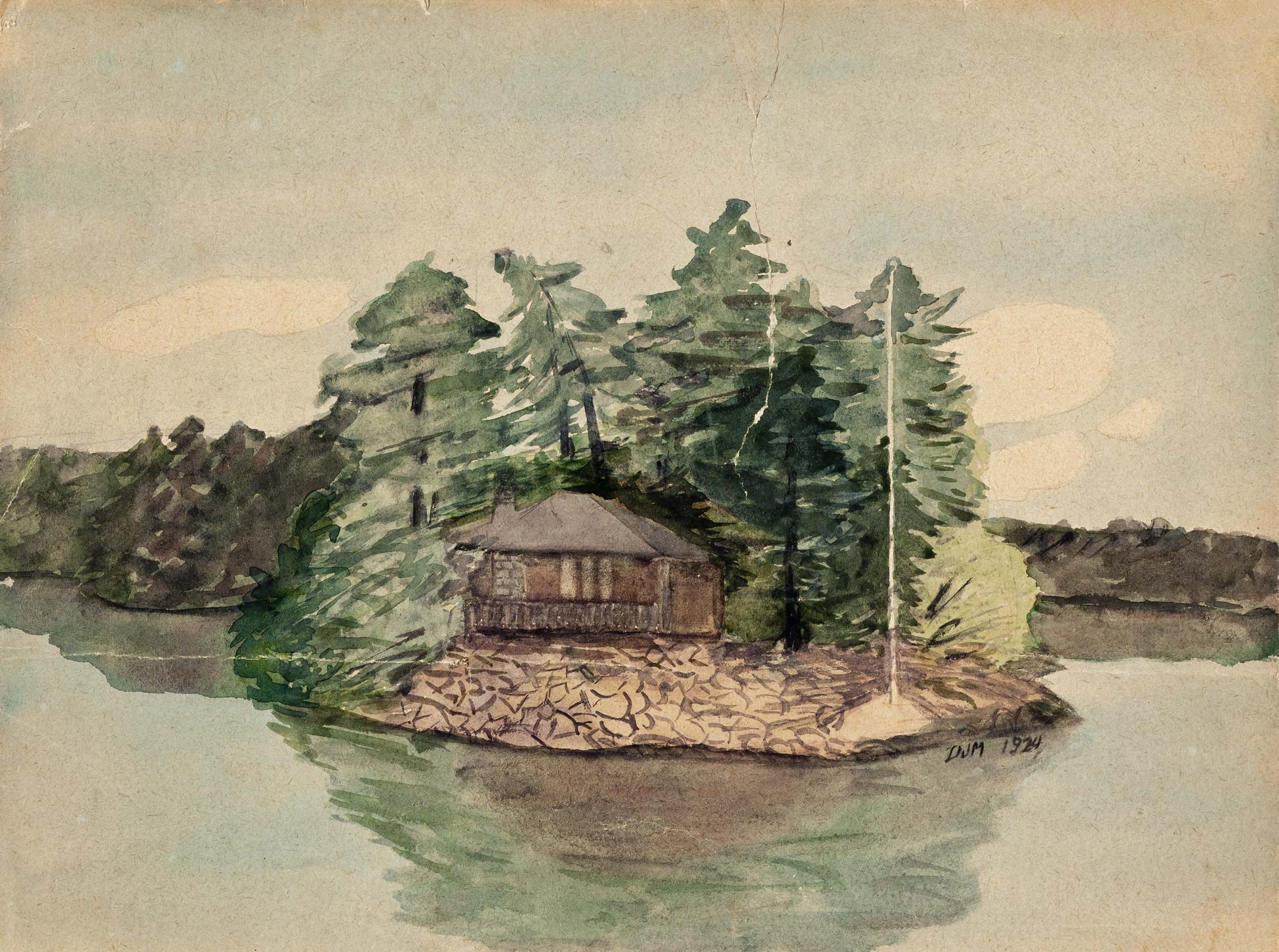

McCarthy’s earliest surviving painting is a small watercolour, Untitled (Dunbarton Island), dated 1924 and initialed “DJM.” It depicts a cottage seen from Silver Island, where the McCarthys began renting a cottage in 1922. Though the paper has yellowed, the brushwork shows promise in its understanding of watercolours and shading. Most interesting is the elevated viewpoint that would become more pronounced as her career progressed.

In 1926, McCarthy and Beer joined Canadian Girls in Training (CGIT), an organization founded in 1915 by major Protestant churches and supported initially by the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). It involved Bible study on Sunday and a mid-week program that, guided by their leader, were “planned, carried out, and evaluated” by the teenage girls themselves. During the summer they also attended camp. McCarthy described her first one as “blissful,” though she wished there had been a better session on sex education. She introduced her Sunday School class at her local Anglican Church of St. Aidan in the Beaches area to CGIT, and this group of around ten girls bonded together for life, calling themselves the Shawnees. To McCarthy’s regret, the fellowship she shared with them never spilled over into her artistic life.

In her last year of high school at the Malvern Collegiate Institute in Toronto, where she rated her art classes a “total loss,” McCarthy attended an art course every Saturday morning at the Ontario College of Art (OCA, now OCAD University). The course was run by Arthur Lismer (1885–1969 ), a member of the Group of Seven, who gave a short talk and an assignment at the start of each class. McCarthy was disappointed that the students were encouraged rather than taught, but she learned “that Canadian art was changing, and that there were painters who were pioneering a new style of landscape painting.” At the assembly marking the end of term, two of her paintings were included in the display and, to the shock of her parents, she was announced as the winner of a full-time scholarship to OCA. By the time they arrived home, the decision to accept had been made—and it changed the course of her life. “I was so happy,” she recalled years later. “I never looked back. I just loved it.”

Art School

McCarthy began her studies at the Ontario College of Art (OCA, now OCAD University) in the fall of 1926. Her initial impressions were favourable, and, although she disliked Lismer’s jokes, she was impressed by his drawing skills and lectures: “I love to watch and listen to him talk.” At the end of her first year, however, as she and a group of fellow students were preparing to go to a “sketching house party” near Kitchener supervised by Yvonne McKague Housser (1897–1996), they heard that Lismer had resigned. He and Principal George Agnew Reid (1860–1947) disagreed over educational reforms at the college. Most of the students in the group immediately quit and formed themselves into the Toronto Art Students’ League, but McCarthy, although she supported them, would lose her scholarship if she left. Moreover, she would need a degree if she wanted to teach in the school system. She carried on with her studies, but for the rest of her life she assessed OCA poorly for both its teaching and its traditional academic programming at the time, which focused on a naturalistic idealism, predominant use of earthy colours, careful application of linear perspective and chiaroscuro, and the absence of any brushwork in the finished work. “I think it was an absolutely lousy training…. I didn’t learn anything about drawing until I went to England.”

What stood out most for McCarthy were the friendships she developed at the college and the events and activities hosted there. She bonded in particular with Ethel Luella Curry (1902–2000), who came from Haliburton, was eight years older, and took her art training seriously: “Too many of our classmates… were content to fritter away the days, but there were some hard-working, creative people with us, and we began to do things together after class.” Curry invited McCarthy to visit her family at the end of 1928, and she was overjoyed by winter scenes in the village of Haliburton and the rustic appearance of their home: “It was like stepping back fifty years,” she wrote.

While at OCA, McCarthy’s interest in religion intensified. She was still involved with the Canadian Girls in Training and participated in major religious conferences such as the Student Christian Movement of Canada meeting in Muskoka in 1927, which hosted theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) and other leading figures. She wished she could combine her two passions: “I was being pulled in two directions. I loved school and was happy with Curry and the gang there, but their friendship was without the spiritual dimension that gave richness to my love for… our widening circle of camp friends.”

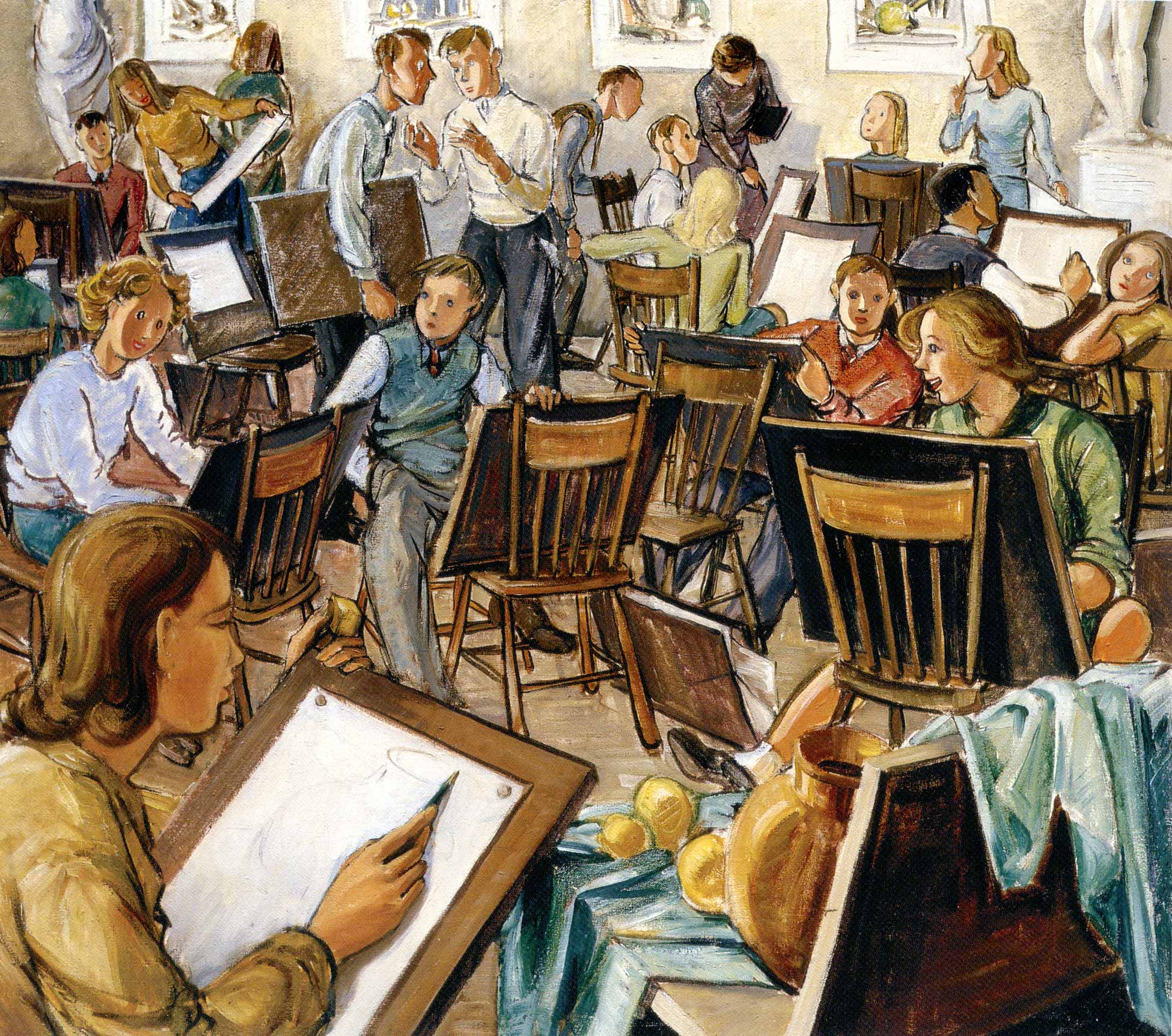

At the end of McCarthy’s final year at OCA, she and Curry were hired to teach Saturday morning classes to children at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), where Lismer was the director of education. They followed his pedagogical approach of encouraging creativity rather than teaching only technical skills. It was McCarthy’s first teaching assignment. Soon after, her father died. It was a devastating loss for her; he was not only a confidant but a strong supporter of her art career.

A year into the Great Depression, McCarthy faced the daunting prospect of looking for work. She earned some money making posters and cards, supplementing the meagre income she received teaching her classes at the art gallery. Early in 1931, her mother went into hospital for surgery and, from the window in her room at Toronto General Hospital, McCarthy painted the view that looked south to the newly opened Royal York Hotel and towering Canadian Bank of Commerce Building. She submitted the work to the Ontario Society of Artists annual open exhibition, where it was accepted—her first success in a juried show.

Teaching Art

At the end of 1931, McCarthy heard of an opening in the art department at Central Technical School (Central Tech). A teacher planned to marry at Christmas, meaning she would have to resign from her position. McCarthy contacted Charles Goldhamer (1903–1985), who had taught her at the Ontario College of Art (OCA, now OCAD University) and was also at Central Tech. He set up an appointment with art director Peter Haworth (1889–1986), who promptly hired her. McCarthy’s first week of teaching was hell: “Peter’s method of teacher training was to fling the novices into the situation and let them fight their own way to the surface.” Her classes were filled with vocational students with little interest in art, and during her first year she frequently thought of quitting, but she needed the money. Haworth preferred to hire artists who he hoped could teach rather than teachers who learned art over the summers. The new staff, however, were still expected to get their teacher training certificates. Under his leadership, the art department flourished as the teachers were able to maintain viable art practices.

McCarthy’s career as an artist progressed well that first year. She joined in a group exhibition at Victoria College at the University of Toronto, and had her first solo exhibition at McGill University in Montreal. The Ontario Society of Artists accepted another of her paintings for its annual juried exhibition. She also received a public commission to decorate the children’s reading room at the Earlscourt Branch of the Toronto Public Library, where she painted murals based on popular fairy tales.

McCarthy registered for her teaching certificate at the Ontario Training College for Technical Teachers in Hamilton. She found the academic courses easy but the practice of teaching challenging. Her critic-teacher was Hortense Gordon (1886–1961), who became a member of Painters Eleven in 1953 and whose understanding of design principles far exceeded anything McCarthy had been taught at OCA: “I was hungry for more intellectual content, and Mrs. Gordon provided it.” In the spring of 1933, McCarthy earned her certificate.

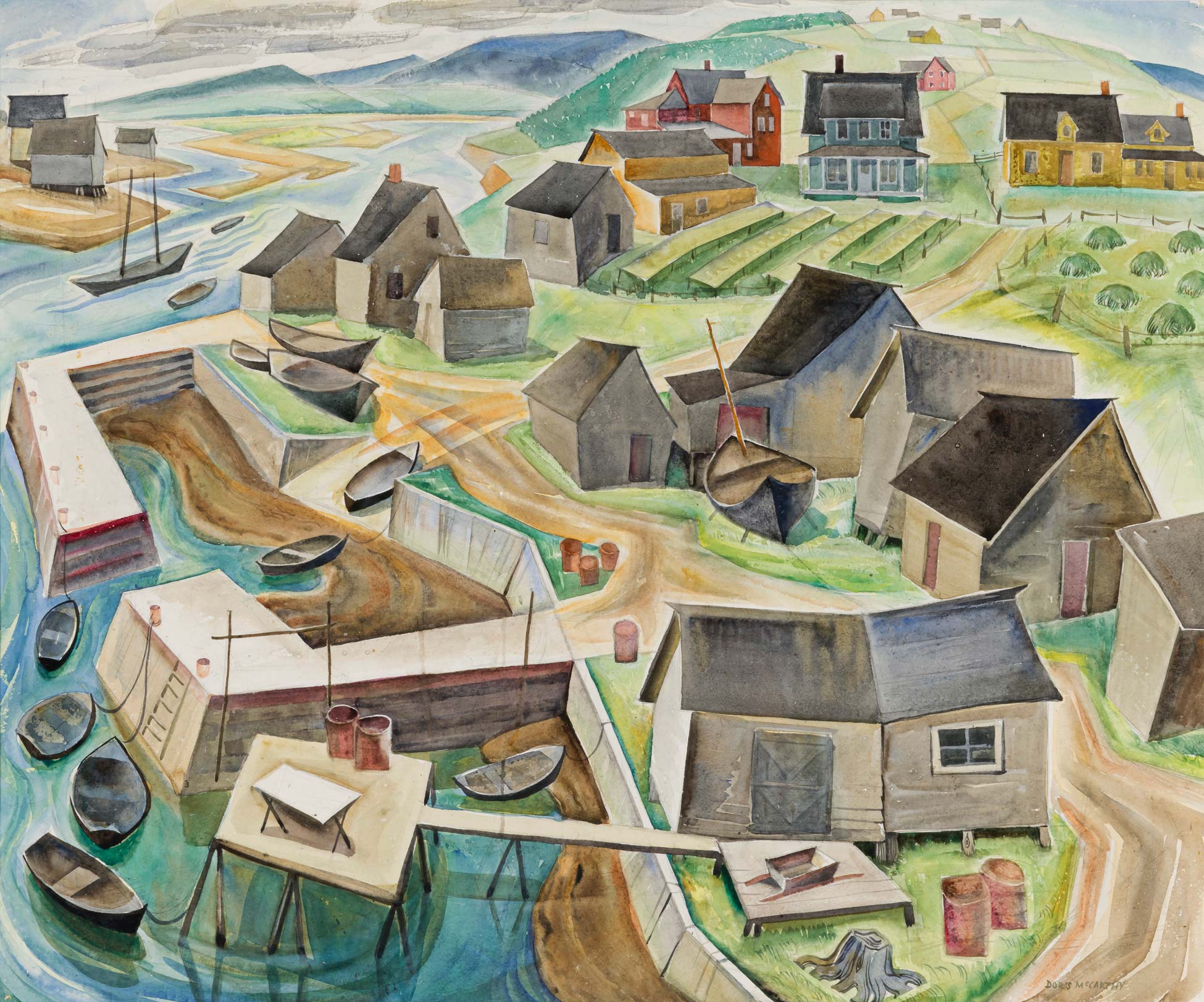

Over the summer of 1933, McCarthy enjoyed the first of many extensive painting trips, this time with Ethel Luella Curry (1902–2000). They went to Ottawa before crossing over the border into Quebec, where they visited Mont-Laurier and then Baie-Saint-Paul, a popular artists’ village, followed by a trek along the south shore of the Gaspé Peninsula. The next summer they went to Peggy’s Cove with Noreen (Nory) Masters (1909–1983), a fellow teacher at Central Tech, and then to the Gaspé Peninsula, stopping at the towns of Gaspé, Mal Bay (La Malbaie), and the fishing village of Barachois, where McCarthy painted Two Boats at Barachois, 1934.

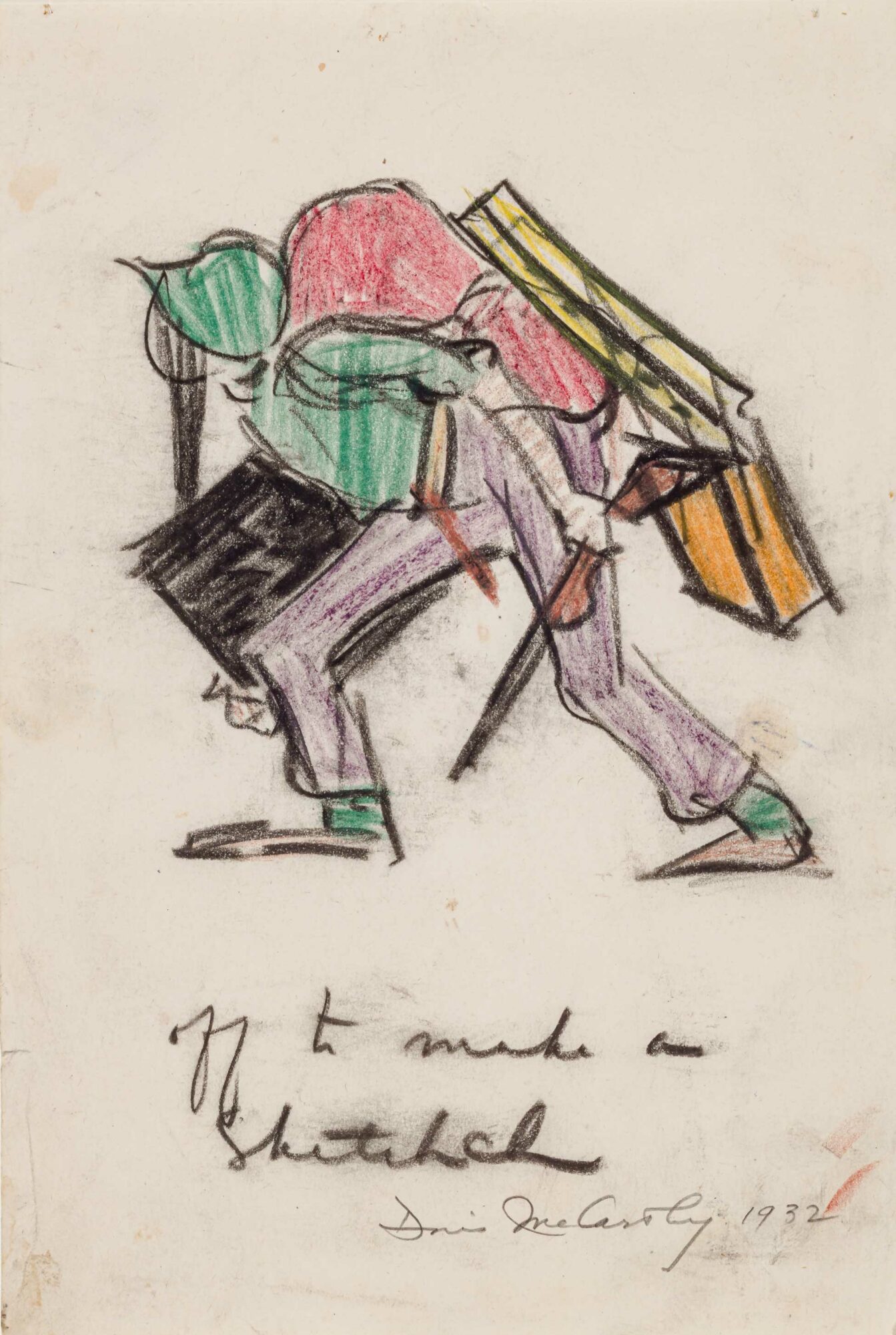

At school, McCarthy was gaining confidence: “At last I had several classes of art students on my timetable, even one third-year group. I felt more reconciled to teaching.” However, she dreamed of going overseas to study for a year and decided on England. She secured an unpaid leave from Central Tech and, on September 27, 1935, with Masters as her travel partner, boarded the SS American Farmer in New York bound for London. They landed on October 6 and settled in a flat in Chelsea.

Europe & the Pacific Coast

When McCarthy and Masters showed up at the Royal College of Art with their portfolios, they were directed to the Central School of Arts and Crafts, which catered to advanced students on short-term study programs. They were impressed with the quality of instruction, even though McCarthy received some brutally honest criticism of her work. She learned a great deal about drawing from John Skeaping (1901–1980 ) and new watercolour techniques from Frederick James Porter (1883–1944), but found life drawing challenging. After an afternoon with Duncan Grant (1885–1978 ), she wrote: “He said that being this good I should be much better, that my drawings were worse than bad because they are mediocre, that I need more sensitive perception. My hand is okay, it’s my eyes and brain that are failing. He told me to use charcoal for a while, to have some fun… to feel more. This advice must have reminded McCarthy of Lismer’s suggestion to “think a think and draw a line around it.”

McCarthy and Masters made the most of their spare time enjoying the sites in and around London, taking a weekend jaunt to Paris, and making new acquaintances. They purchased a car and spent the last six weeks touring England and Scotland, painting as they journeyed and producing works that were similar to their earlier images at home. McCarthy noted that the lessons she learned at Central Technical School (Central Tech) took time to percolate, but they eventually found their way into some of her most important early mature works, such as The Complete Barachois, 1954.

During their return voyage in late summer 1936, McCarthy spotted her first iceberg: “We tore to see it and watched it grow from a light speck to a lovely fairy creation of white and green shadows.” Little did she know that she had caught her first glimpse of a subject that would dominate her late work.

The following summer, McCarthy journeyed out west for the first time. After a stop in Jasper, she travelled the Pacific coast from Prince Rupert to Vancouver and then visited Revelstoke in the B.C. Interior. The Rocky Mountains offered an entirely different landscape, and, though she struggled to translate a sense of their size into her paintings, she welcomed the challenge with some striking and colourful results, as witnessed in Mountains Near Revelstoke, B.C., 1937.

In the fall of 1938, McCarthy began to look for a place of her own. In November, she found a block of land near the Scarborough Bluffs on which to build her new abode: “A heavenly spot, twelve acres on the corner between the bluffs and a great lovely ravine, nature on three sides, my beautiful lake, the ravine, the broad fields like Normandale. It’s a perfect spot!… Mother labelled it ‘that fool’s paradise of yours,’ and I put it in capital letters and made it official.” A year later, McCarthy moved out of the family home. Tensions between her and her mother had reached a boiling point. She found a bungalow in the Beaches neighbourhood to rent, relatively close to her land.

A Career in Art

With the outbreak of the Second World War, fellow teachers Charles Goldhamer and Carl Schaefer (1903–1995) were recruited as war artists, leaving McCarthy with senior drawing and painting classes filled with students who were interested in art. Masters married during the summer of 1940, and Virginia Luz (1911–2005), a former student, took over her position. Before long, McCarthy and Luz became fast friends.

Meanwhile, McCarthy progressed with building her dream home, Fool’s Paradise, using the skills her father had taught her. Another fellow teacher, Bob Ross, designed the pine weather vane depicting an angel that became its “brand.” McCarthy included it in some of her works.

McCarthy exhibited frequently during the war, in part due to the increased opportunities for women artists, and her work gained more critical attention. Generally, her paintings had not evolved noticeably, although technically they demonstrated a high degree of skill—such as Haliburton, New Year’s Eve Day, 1940, for example. After a solo show at the Simpson’s Department Store in Toronto in 1944, she was finally elected as a member of the Ontario Society of Artists. This moment marked her arrival as a professional artist, or, as she put it, “an artist among artists.” Up to that point, McCarthy likely saw herself as more of a teacher than an artist and was not highly motivated to advance her work. This recognition, along with her continued exposure to landscapes by contemporaries such as Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986) and Isabel McLaughlin (1903–2002), encouraged her to forge a more unique approach.

When her colleagues returned at war’s end, McCarthy was again relegated to teaching junior classes at Central Technical School (Central Tech)—and she was not happy about it. She found solace in completing Fool’s Paradise, as she proudly called it, at the end of 1946—and she lived there for the rest of her life.

In August 1948, when wartime restrictions on gasoline had lifted, McCarthy travelled to Rockport, Maine, and then to the Rocky Neck Art Colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts. She visited the studio of Umberto Romano (1906–1982), a minor American Expressionist painter who ran a school there. McCarthy was intrigued by the vivid, rich colours of the paintings she saw there: “I came out somewhat drunk on colour and paint, and determined to throw caution into the tidal pools.” It marked the beginning of her “Post-Romano period,” when she introduced bright colours and a looser approach in her work, as found in Red Rocks at Belle Anse, Gaspé, 1949.

Around this time, McCarthy and her mother improved their relationship, though when the latter finally visited Fool’s Paradise in the summer of 1949, she fell down the cellar stairs and broke her back. Still, “from then on,” McCarthy wrote, “Mother accepted me as her daughter, her confidante, her support.” Reflecting on turning forty in 1950, McCarthy wrote: “I was no longer self-conscious about my failure to marry. Instead I had accepted my status as a single woman and discovered that there were rich consolations…. I had become a happy teacher…. I had my own home…. What I still wanted… was growth as an artist.” She celebrated the next part of her life with a memorable year of travel.

Travels & Maturity

In June 1950, McCarthy and Virginia Luz set out for Europe on a year-long sabbatical. Their first painting location was the west coast of Ireland, where they sketched the countryside of Connemara. Initially, McCarthy was not happy with her work: “Those days painting in Ireland would have been idyllically happy if I could have relaxed and been content to record the country and the weather. Instead, I kept demanding of myself that I should be producing Great Art…. Later I could see that my sketches did capture the moodiness of the constantly changing light and the unaccustomed brilliance of the wet Irish colour.”

McCarthy and Luz next began a driving tour of England and Scotland. McCarthy was particularly impressed by the Gothic cathedrals—a subject she had included in her art history course at Central Technical School (Central Tech). They thoroughly enjoyed the theatre productions they saw—John Fletcher and William Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, T.S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party, and Christopher Fry’s Ring Around the Moon (an adaptation of Jean Anouilh’s Invitation to the Castle). But McCarthy’s greatest excitement was meeting Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), whose books she had been reading since childhood and who agreed to have lunch with her.

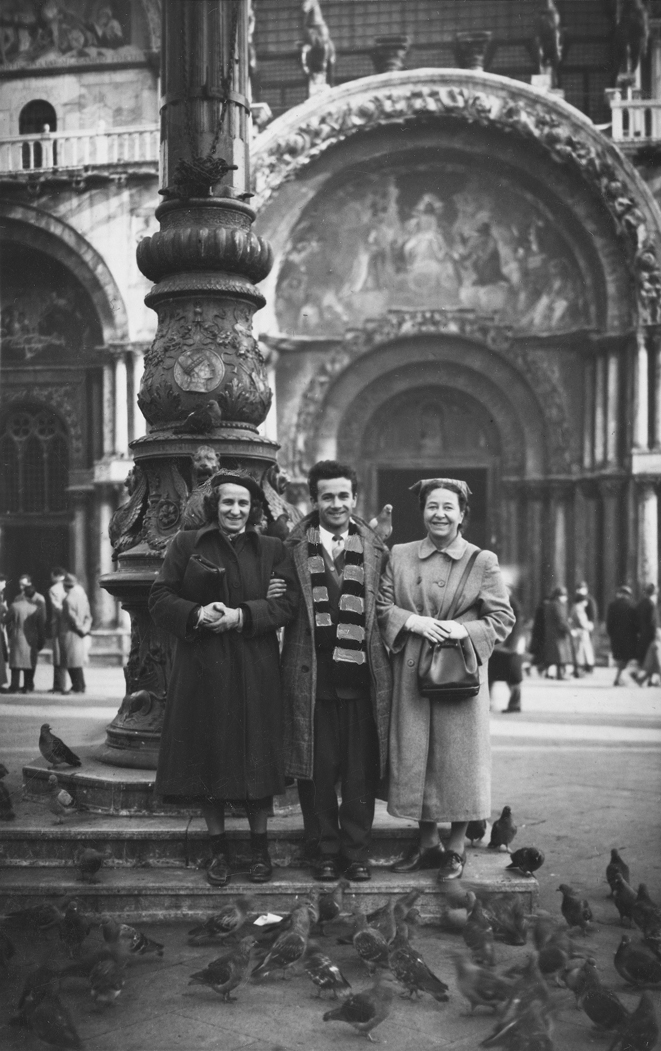

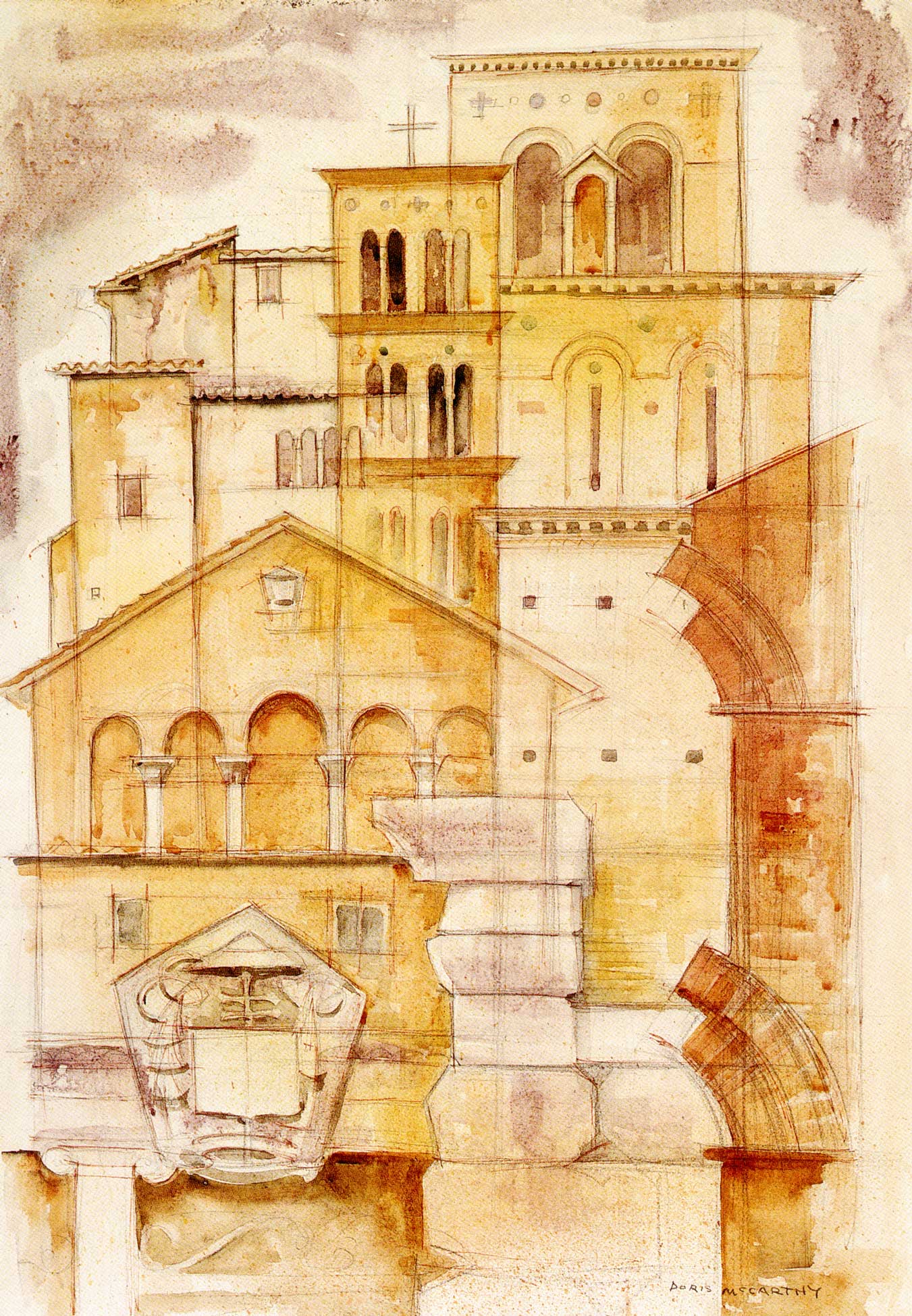

Next, McCarthy and Luz went to Holland and Germany, where Christmas in Düsseldorf was a highlight. They then drove through Austria to Northern Italy and met up with a former student, Stanislao Dino Rigolo (b.1924), who guided them through Venice, Ravenna, Florence, and Tarquinia. McCarthy’s work was richly varied, as she adapted her style to the character of the various locations they visited.

In early February, McCarthy and Luz arrived in France, where again they sketched and painted. After a side trip to Greece, they visited Paris and finally headed back to England and Ireland, returning to the places they had enjoyed sketching months before. Their “wonderful year” ended just days before their fall classes resumed at Central Tech. It had exposed McCarthy to a cornucopia of art, culture, and geography that enriched her art historical knowledge, a subject she taught. All these experiences broadened her palette and loosened her style, giving her an almost chameleon-like ability to capture the character of the places she chose to portray.

-

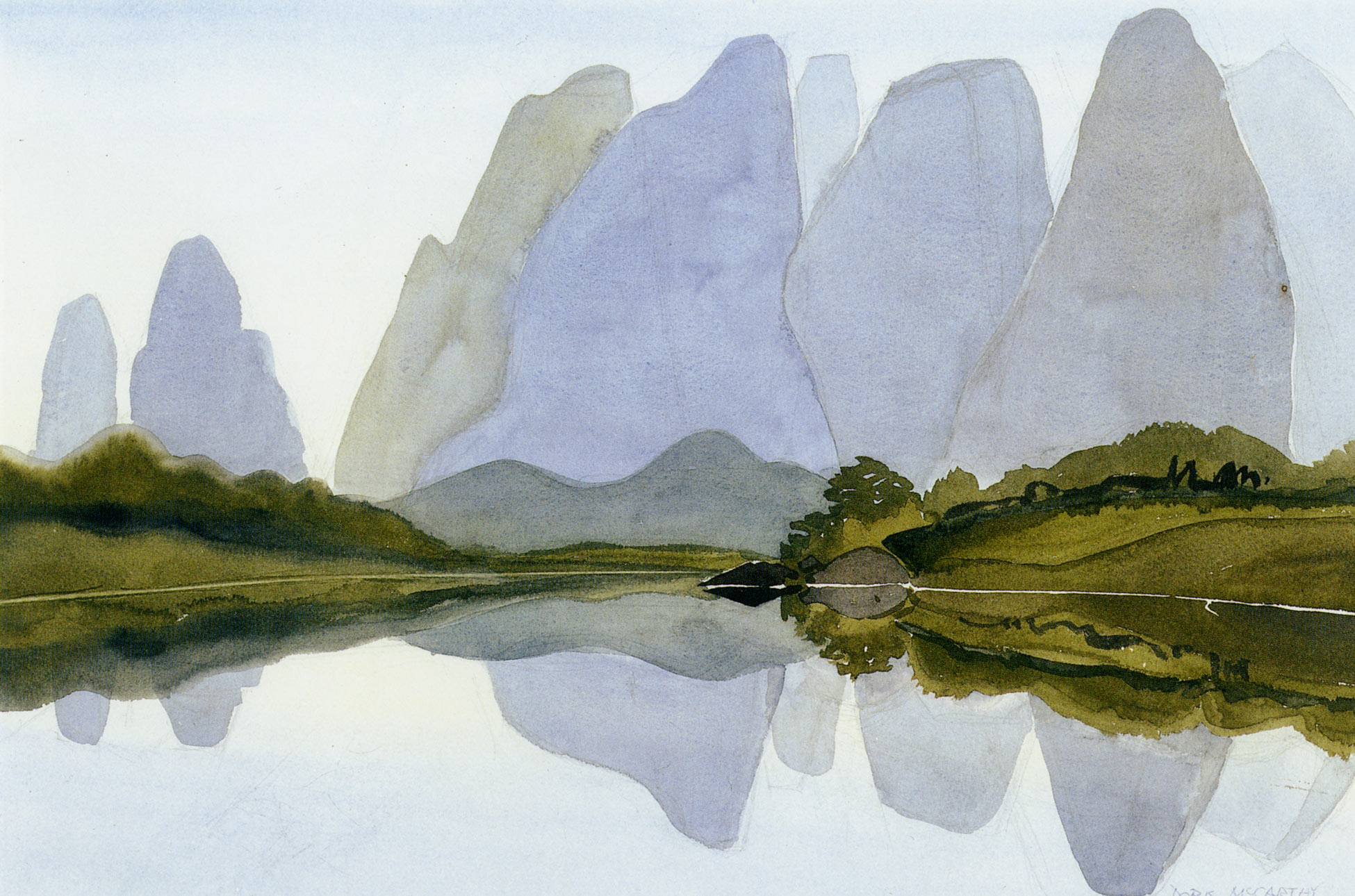

Doris McCarthy, The Government Pier at Barachois, 1954

Oil on canvas, 61 x 68.6 cm

Doris McCarthy Gallery, Scarborough -

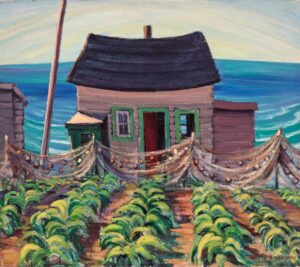

Doris McCarthy, Tea Party at the Opening, 1947

Watercolour and brush ink on paper, 53.3 x 78.7 cm

Doris McCarthy Gallery, ScarboroughThis work is an example of McCarthy’s watercolours.

-

Doris McCarthy, Whitby from Above, 1958

Watercolour and ink on paper, 61 x 76.2 cm

Doris McCarthy Gallery, ScarboroughThis work is an example of McCarthy’s watercolours.

The year that followed was a productive one for McCarthy, with six solo shows, several two-person exhibitions with Luz, and nine group exhibitions, even though Toronto had few commercial galleries at the time. As her reputation blossomed, she sold more of her paintings and, in 1951 and 1952, was elected first as an associate of the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts and then to the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour. She went on to serve as secretary of the watercolour society from 1953 to 1955 and as president in 1956.

McCarthy’s annual painting trips to the Gaspé Peninsula and Haliburton continued, producing some iconic pieces such as the angular, Cubist-like The Government Pier at Barachois, 1954. These excursions were punctuated by her return to Europe during the summers of 1955 and 1958. Goldhamer succeeded Haworth as head of the Art Department at Central Tech, and McCarthy moved on to teach more senior painting classes. Her personal life settled down substantially in the late 1950s too. With four friends, she bought two neighbouring cottages on Georgian Bay, and in 1960 added a studio to Fool’s Paradise. Later that year her mother died, and McCarthy remembered her fondly: “Mother gave me the strong constitution, the physical and emotional energy, the organizing capacity, and the love of an audience that are among my most conspicuous gifts.”

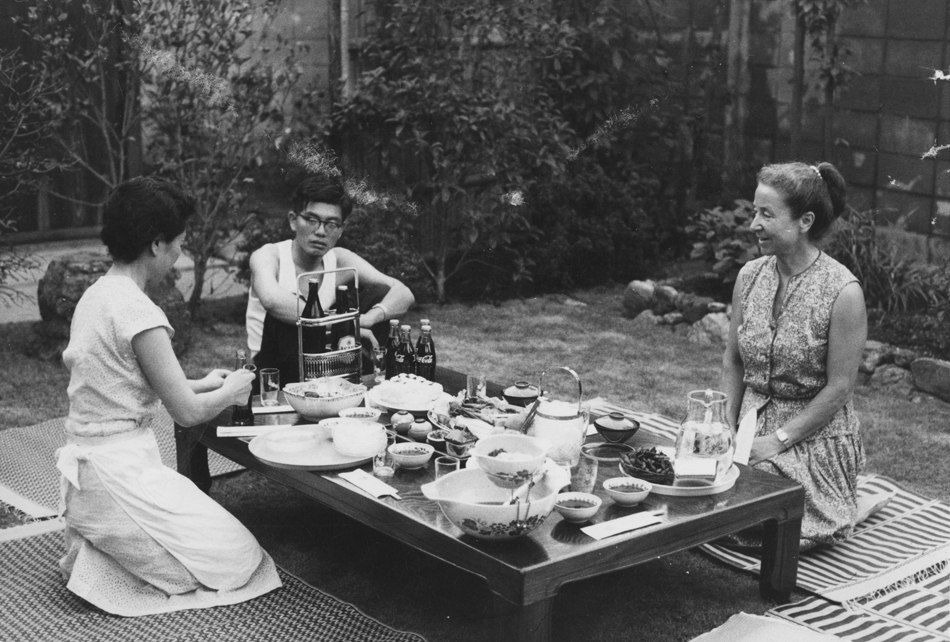

At the end of June 1961, McCarthy set off alone on a year-long journey around the world. In part, she wanted to photograph the sites and works she had been teaching in her art history class, and she had applied for a Canada Council grant to fund the trip. Her request was refused, but a bequest from her mother enabled her to continue with her plan. She began in San Francisco and moved on to Japan, but she thought her paintings there were uninspired and destroyed most of them. After Hong Kong, she hoped to visit China, but when her visa was declined, she went on to New Zealand. There, her enthusiasm for sketching returned: “I can remember sitting on a grassy hillside… saying out loud to myself, ‘Talk about it. Don’t try to imitate it. Tell it, don’t show it.’ At that point a little magic began to creep in.”

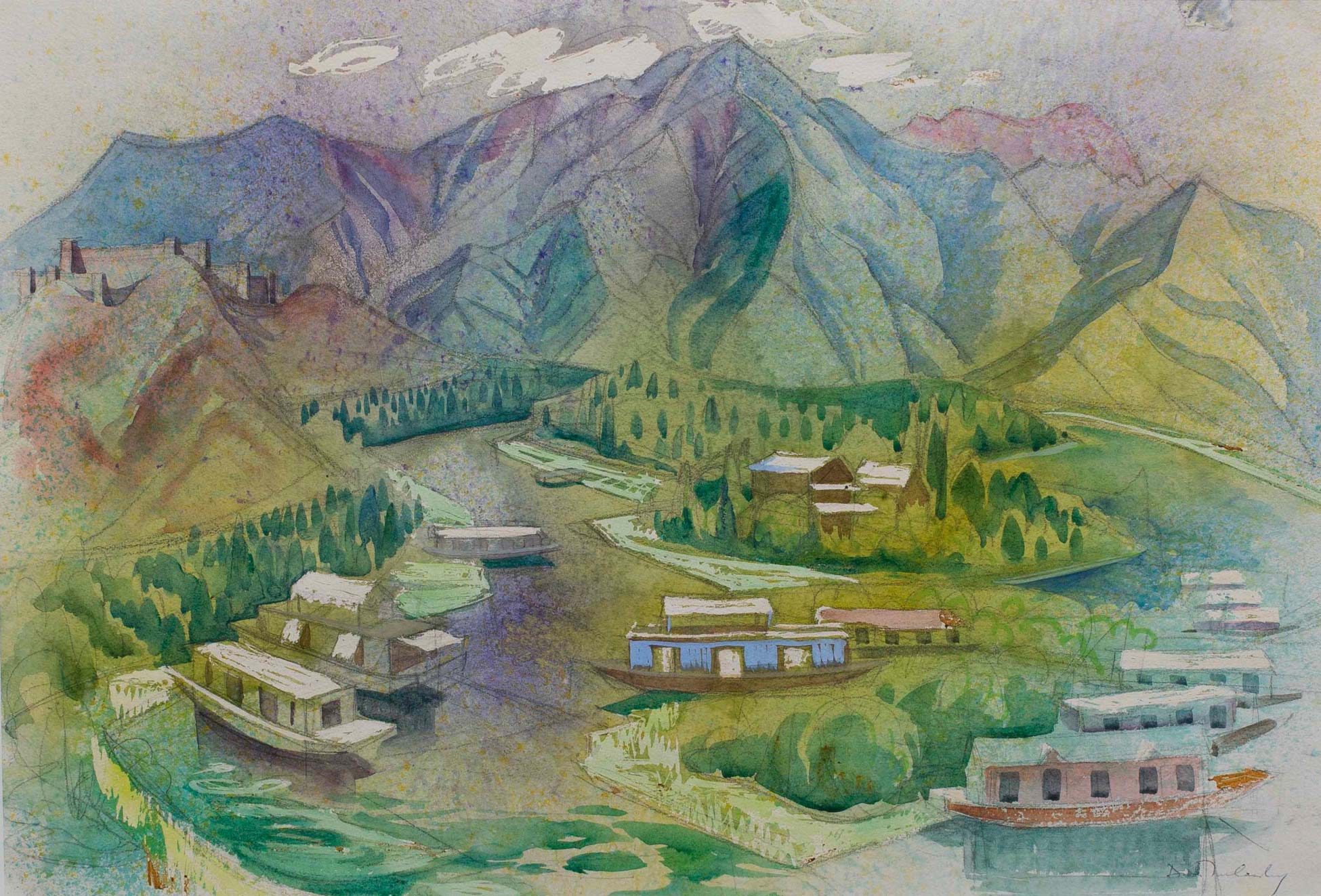

McCarthy next headed to Singapore, Thailand, and Cambodia, where she visited the temple complex of Angkor Wat. India turned out to be “too rich, too diverse, too crowded, and too difficult for me.” Her adventures took her next to Afghanistan, then Iran (where she visited the remains of the ancient city of Persepolis), followed by Iraq, Lebanon, and Turkey, where, in Istanbul, she marvelled at the Hagia Sophia. Istanbul became her third favourite city after London and Rome. She went on to Greece and Egypt, where she took pictures of the Karnak Temple, and spent Christmas in Israel. Everywhere she took photographs. In Rome, she again met her former student Rigolo before going on to Spain (where she visited the Caves of Altamira), the south of France, and finally England, where, as planned, she met up with Luz.

It had been a long year travelling the globe alone, but McCarthy concluded that she didn’t have any regrets: “The thousands of slides of sculpture and architecture that I carried home made it possible for me to give students a vivid experience of the art of the distant past and share with them my enthusiasm for it.” Her creative output was prodigious as usual and she painted some remarkable scenes, especially exquisite watercolours of Rome, refining the lessons she had learned during her previous year-long trip with Luz.

On returning to Toronto, McCarthy noted a change in the art scene: “[It] was livelier…. Catalogues of the juried exhibitions of the sixties show an eclectic mixture of styles and points of view, with abstraction and abstract expressionism increasingly dominating the galleries. Montreal and New York seemed to be providing much of the inspiration. Jack Bush… was now producing large colour field canvases, to critical acclaim.”

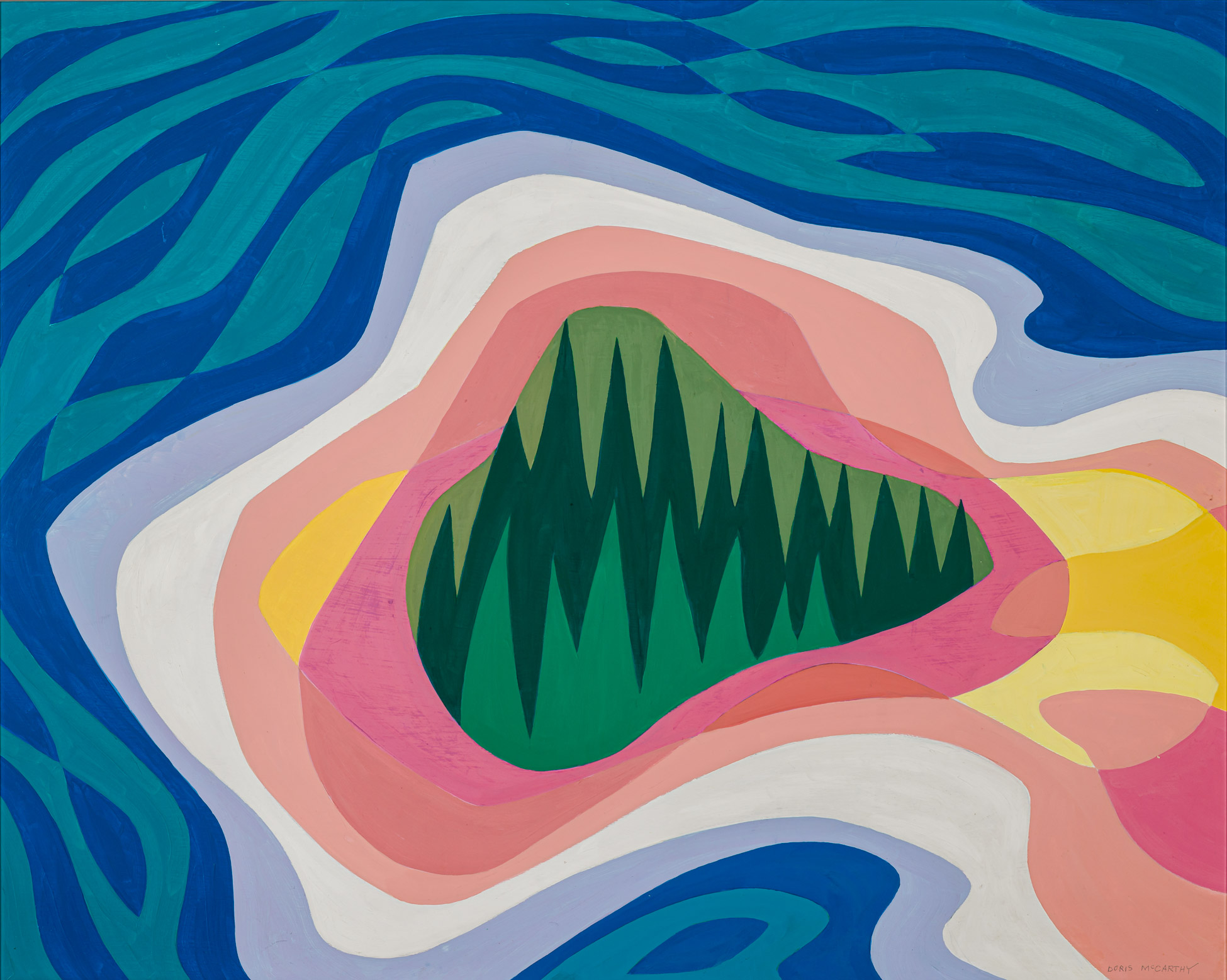

The late 1950s and 1960s would be a period of experimentation in the art world, producing work that was very different from the more traditional fare of McCarthy’s landscapes. Yet, as a teacher, she felt she needed to keep up with the times. Inspired in part by her students, McCarthy began to experiment with Abstract Expressionism and the hard-edge style of colour-field painting with startling results. Among the former, Rocks at Georgian Bay I, 1960, offers frantic, choppy brushwork in swirling patterns, punctuated by tracks of blue, green, purple, and yellow, generating a landscape version of the gestural abstraction of some of the Painters Eleven and their American sources of inspiration.

Success

In 1964, McCarthy became the first woman to be elected president of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA). Her tenure there was marked by some significant changes. The Art Gallery of Ontario, led by director William Withrow (1926–2018), began to sever its ties with both the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the OSA as it sought to bolster its international reputation. Provincial funding to the OSA was also cut. Moreover, McCarthy became a defence witness in an obscenity trial of gallery owner Dorothy Cameron (1924–2000) and the Eros ’65 exhibition she mounted in 1965. She created and participated in a weekly radio show, OSA on the Air, which was broadcast on CJRT-FM.

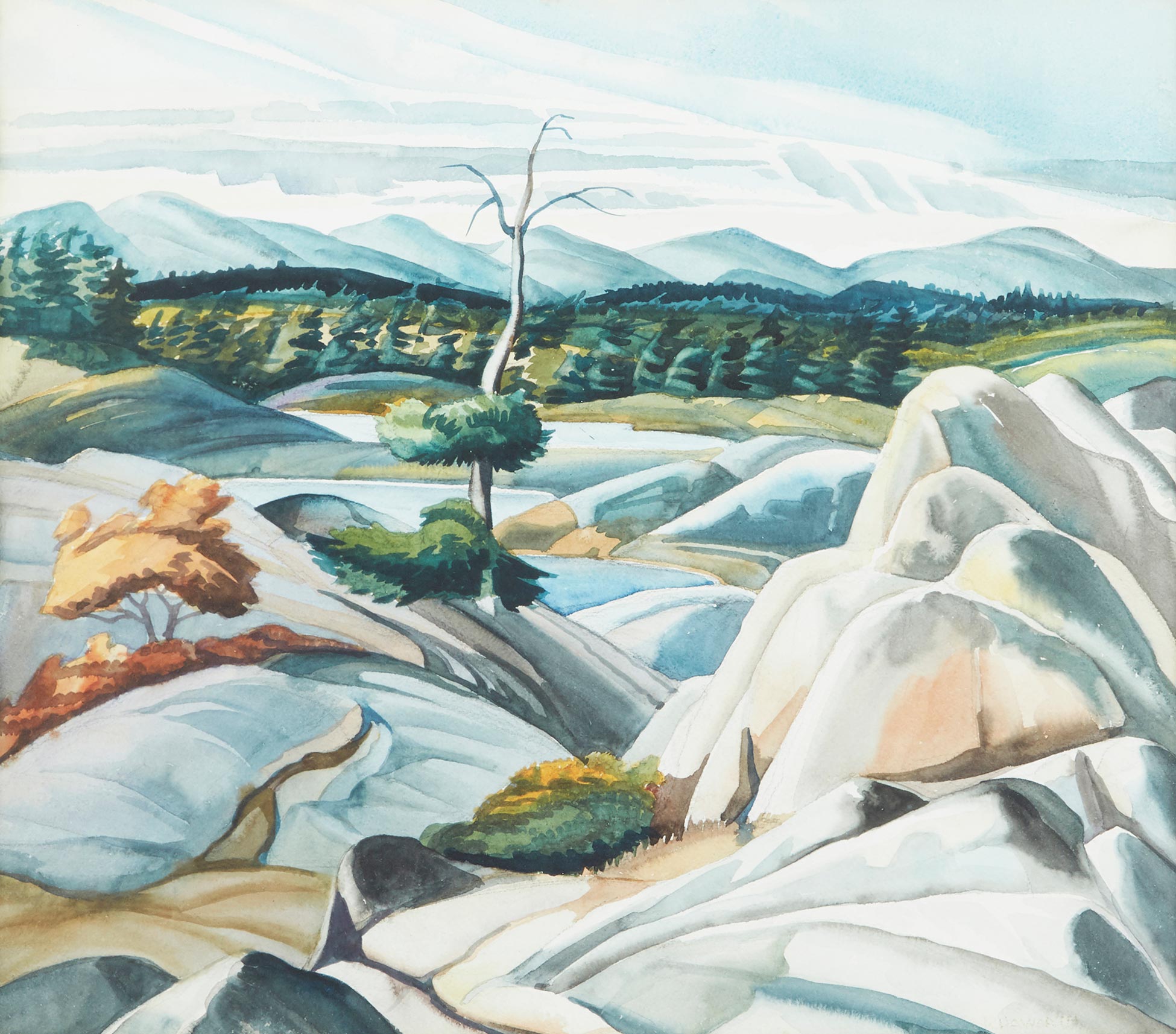

During this busy period in her life, McCarthy experimented with hard-edge landscape paintings. These works are among the most unique, contemporary, and memorable of her oeuvre. Although they push against the boundary between representational and abstract art, she approaches them with an ease and familiarity that gained her professional recognition: “I was working with simplified colour field and hard-edge painting …. [I escaped] to Georgian Bay… where I tried to say the rocks and water movements in the simplest way possible…. In this most hectic time of my life, my work had a serenity that was new.

As McCarthy approached sixty, Laszlo (Leslie) Reichel, a young Hungarian immigrant who admired her art, acquired approximately forty of her paintings and, after framing them, organized an exhibition at the Gutenberg Gallery on Toronto’s Yonge Street under the title Doris McCarthy. When they all sold, other dealers realized there was a market for her art, and she soon found it challenging to keep up with the demand.

In the mid-sixties, when Virginia Luz was promoted over her at Central Technical School to be assistant head of the art department, McCarthy was “devastated.” She held on, and three years later she accepted a commission to design a flag for the city of Scarborough. Her abstract design of the red maple leaf and the bluffs overlooking the waves of Lake Ontario is still in use today. In 1969, Luz became the head of the department, and McCarthy was appointed assistant head. They worked well together, and the new responsibilities made McCarthy’s final years at the school more enjoyable.

The Best Years

After four decades at Central Technical School, McCarthy decided to retire. Curiously, she didn’t think she would continue her art: “I thought I was painting to be a good teacher and that once I stopped teaching I’d stop painting.” Fortunately, she used the gratuity she received on retiring to go to the Arctic with Barbara Greene (1917–2008), an adventurous new teacher at the school.

On July 5, 1972, McCarthy and Greene began the voyage north, first to Resolute Bay and then on to Eureka, Grise Fiord, and Pond Inlet. McCarthy experienced a variety of adventures, including falling into a frozen creek and being flung off a dog sled. But they also observed the culture and customs of the local Inuit population, meeting Joan (Colly) Scullion and John Scullion (the settlement manager at Pond Inlet), and visiting an iceberg: “This was the first time I had seen the brilliant turquoise and incredible green of the deep crevasses of glacial ice.” McCarthy was smitten by the North and returned frequently, producing an impressive body of work that captures the subtle colours, lighting, and majesty of the forms of the region, in particular the icebergs.

Once retired, the energetic McCarthy embarked on several other new ventures. She enrolled in classes at the University of Toronto, earning a BA Honours in English literature in 1989. When her lifelong friend Marjorie Beer died in 1974, she organized the creation of religious banners that were hung at Toronto’s Metropolitan United Church as her memorial. They became “the beginning for me of a series of liturgical wall-hangings.” In fact, McCarthy had made her first tapestries in 1956 and 1957, part of an ongoing interest in trying out various media that included designing puppets, printmaking, and wood carving. She was tireless in all aspects of her life.

In 1975, McCarthy decided to change her gallery representation and approached The Pollock Gallery, located on Dundas Street opposite the Art Gallery of Ontario. Jack Pollock (1930–1992) agreed—on the condition that she paint larger pictures. She switched to 5 x 7 foot canvases, but by the time she had sufficient work for a solo show, Pollock’s gallery had closed. She was picked up by the Merton Gallery, which “proved to be an excellent location… and spacious enough for my new large canvases.” In the spring of 1973, she became a “full member of the Royal Canadian Academy with one of my iceberg fantasies accepted as my diploma piece.” The submitted work was Iceberg Fantasy before Bylot, c.1974, a beautiful Arctic scene painted in varying shades of white and pale blue applied to a mix of opaque and transparent forms. When the Merton Gallery closed in late 1978, McCarthy approached the Aggregation Gallery on Front Street run by Lynne Wynick and David Tuck (renamed Wynick/Tuck Gallery in 1982). They represented her very successfully for the rest of her life—and continue in that role.

In the spring of 1982, McCarthy and two friends rented a recreational vehicle and headed west to the Canadian Badlands in Alberta, where Wendy Wacko filmed her for the documentary Doris McCarthy: Heart of a Painter (1983). Despite many misadventures, the film was completed and premiered in Toronto, followed by screenings in New York and London. McCarthy enjoyed the entire experience and played the film at every opportunity.

In 1986, McCarthy received the nation’s highest honour, the Order of Canada. Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), a former student who had been influenced by McCarthy, had nominated her, and the photograph with Governor General Jeanne Sauvé became McCarthy’s second-favourite photo, “after the Arctic Bay igloo.”

Inspired by her course in creative writing as part of her degree, McCarthy embarked on her two-volume autobiography, A Fool in Paradise: An Artist’s Early Life (1990) and The Good Wine: An Artist Comes of Age (1991). Both were well reviewed.

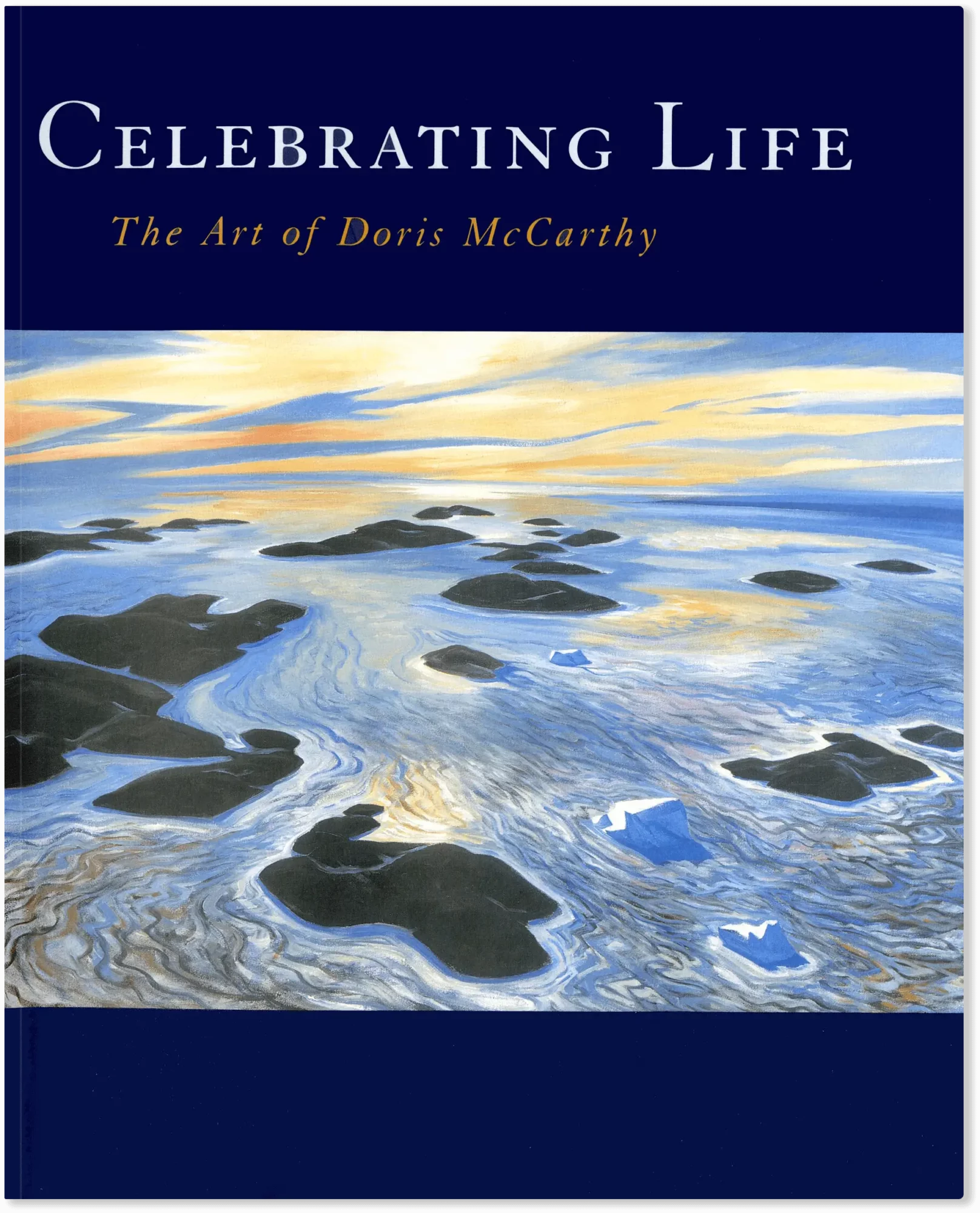

McCarthy’s first major retrospective, Doris McCarthy: Feast of Incarnation, Paintings 1929–1989, opened at Gallery Stratford in May 1991, before touring to nine galleries in Ontario and one in Quebec. The following year, she was appointed to the Order of Ontario and received the first of five honorary degrees. In 1996, the City of Scarborough proclaimed June 4th “Doris McCarthy Day.” The decade ended with another retrospective, Celebrating Life: The Art of Doris McCarthy, organized by the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in 1999 and 2000.

Meanwhile, McCarthy’s thirst for travel continued during the 1990s, with trips to Spain, the Antarctic, Hawaii, England, Ukraine, Portugal, China, New Mexico, and Arizona, as well as visiting her usual haunts in Canada. Still, recognizing her age, she decided to designate Fool’s Paradise as an artist’s retreat managed by the Ontario Heritage Trust. Since 2015, the property has hosted an important artist-in-residence program that has included children’s book author Kathy Stinson and artist Tristram Lansdowne. McCarthy also completed the third volume of her autobiography, Doris McCarthy: Ninety Years Wise (2004).

55.9 cm, private collection.

McCarthy started to slow down heading into the new millennium, although her curiosity and lust for life never waned. She continued to paint, in watercolour, and wrote a new chapter for the condensed version of her autobiography, Doris McCarthy: My Life (2006). On November 25, 2010, McCarthy died peacefully at Fool’s Paradise at the age of 100. The last retrospective of her work, Roughing It in the Bush, opened in the gallery bearing her name that same year and introduced her most abstract landscapes from the 1960s, which had rarely been seen. They further solidified her place in the history of Canadian art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements