Carl Beam drew his artistic influences from a wide array of sources, including historical Indigenous iconography and traditional ceramics methods, the innovative printmaking techniques of Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), contemporary video, and performance art inspired by Joseph Beuys (1921–1986). Ever experimental and innovative, Beam blended abstract and figurative modes, often in jarring juxtapositions. His work is intimate and autobiographical, symbolic and critical, poetic and monumental. His purpose was always to challenge viewers to consider the damage caused by European colonialism and the annihilation of Indigenous peoples, their culture, and their spirituality.

Semiotics as Subversion

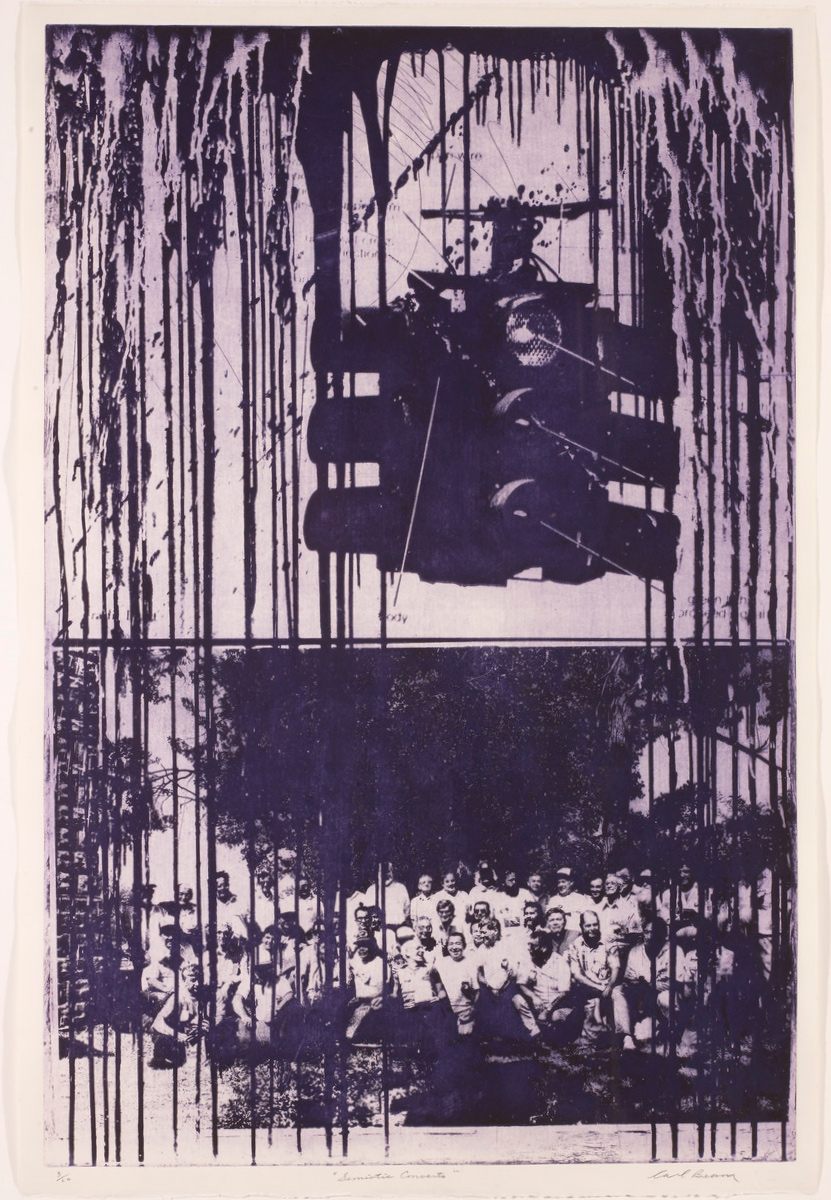

Virtually all of Beam’s work is informed by semiotics, a critical theory he was introduced to while pursuing an MFA at the University of Alberta between 1975 and 1977. The word “semiotic” appears frequently in his work, in either the textual elements of the imagery or the titles of many of his pieces (such as Semiotic Converts, 1990). Though he abandoned his degree when he was discouraged from studying contemporary Indigenous art in any critical and meaningful way, he continued to engage with semiotics throughout his artistic career.

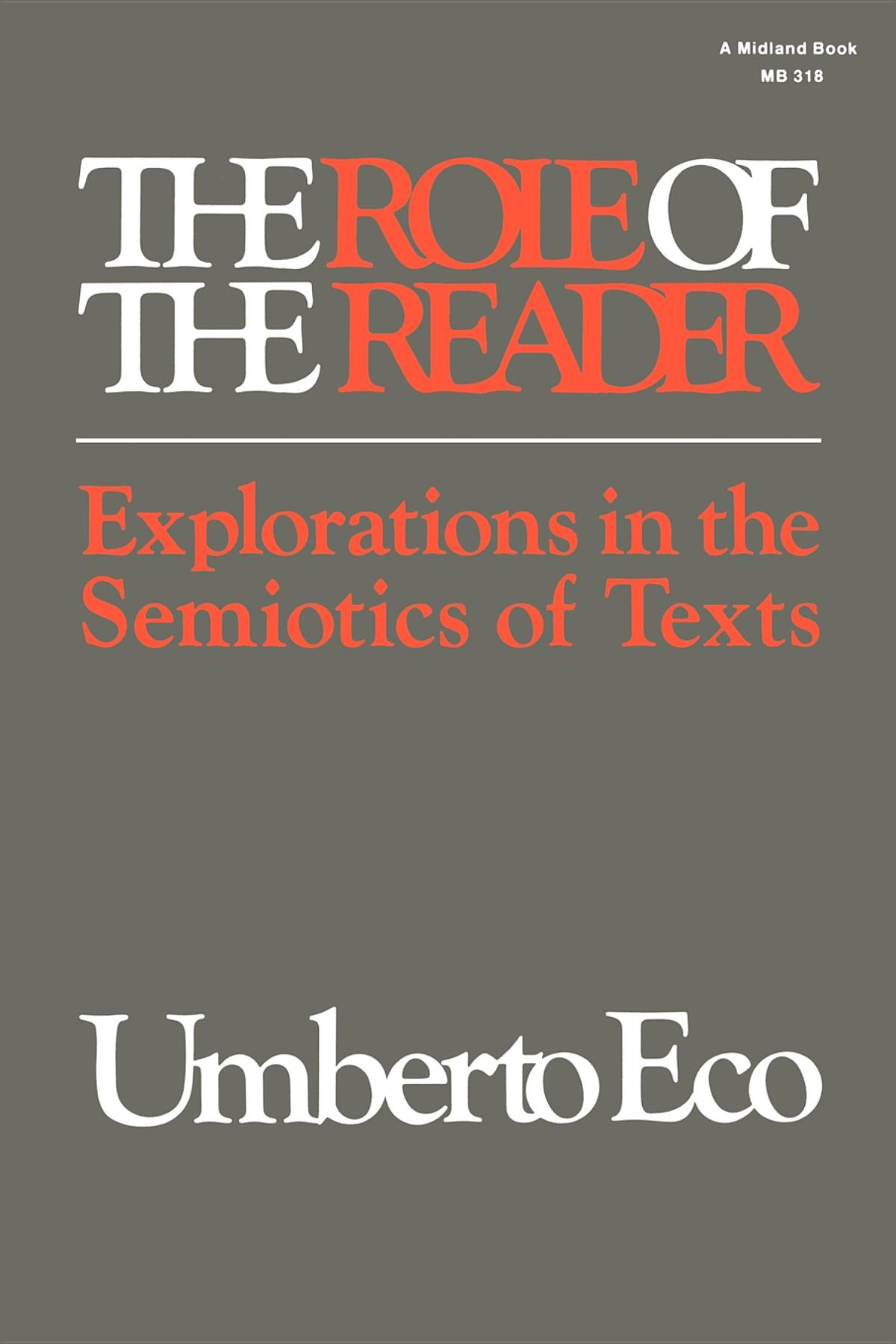

As a theory, semiotics explores the significance of visual signs and symbols that communicate meaning beyond written language. Beam wanted his works of art to be complex purveyors of meaning, and to operate on several levels—metonymic (figurative), metaphorical, and contextual. He found in semiotics an expansive conceptual and creative framework that allowed him to express many things at the same time. He read and was influenced by Umberto Eco (1932–2016), a prominent semiotician whose theories on the “open text” argued that literature and art are fields of meaning rather than prescribed narratives that can be read only one way. Beam embraced Eco’s theories advancing the idea that open texts are dynamic and convey meaning as experiences dependent upon personal interpretations of signs and vocabularies. He approached his art through this elastic lens, viewing his compositions as open image fields that provoke reflection upon the very process of developing meaning.

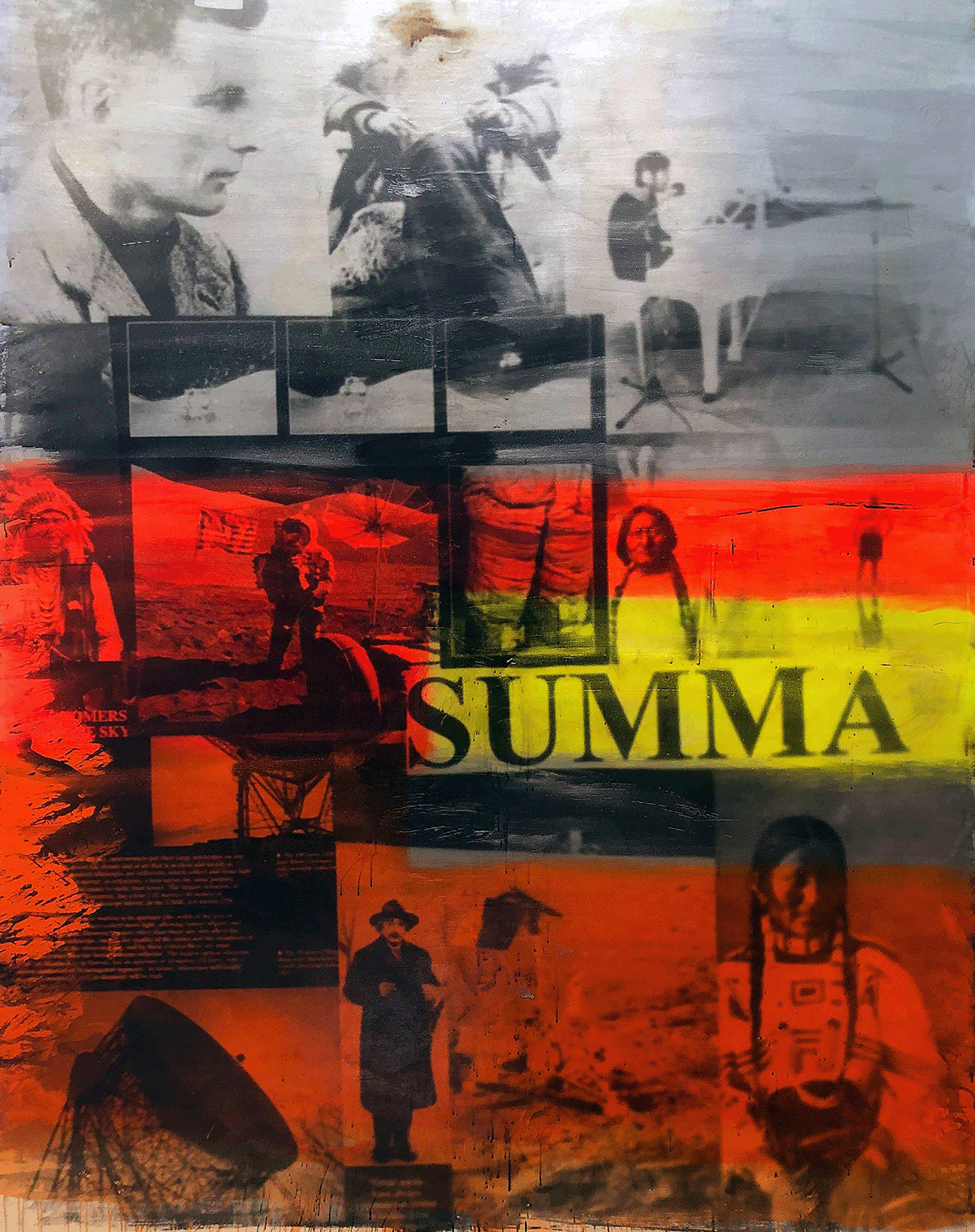

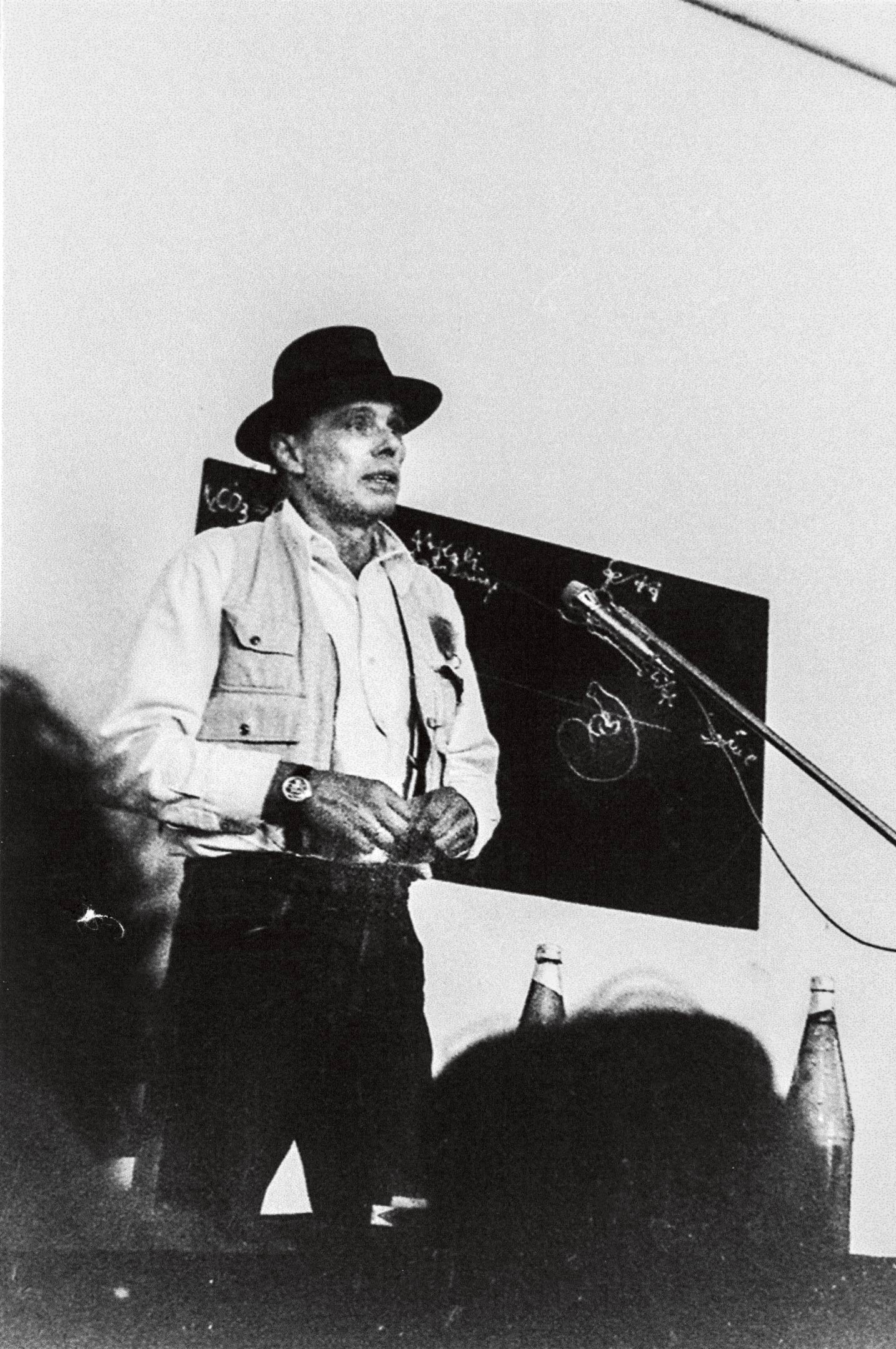

In experimenting with the parameters of meaning-making, Beam’s approach echoes that of German Conceptual and performance artist Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), who explored the relationships between thought, speech, and form through performances involving symbolic gestures and materials such as felt and honey. Beam admired Beuys (the artist is even pictured, headless, in Beam’s monumental painting Summa, 2003), and he shared his conviction that art should subvert dogmatic messages and challenge viewers to form their own knowledge. Semiotics gave Beam the philosophy and techniques of subversion, which he then used to expose the absurdities and deceptions at play in his and our times. It also allowed him to experiment with different media and practices of making—from collage and photo emulsion to video- and performance-based expression—which helped his art to evolve over the course of his career.

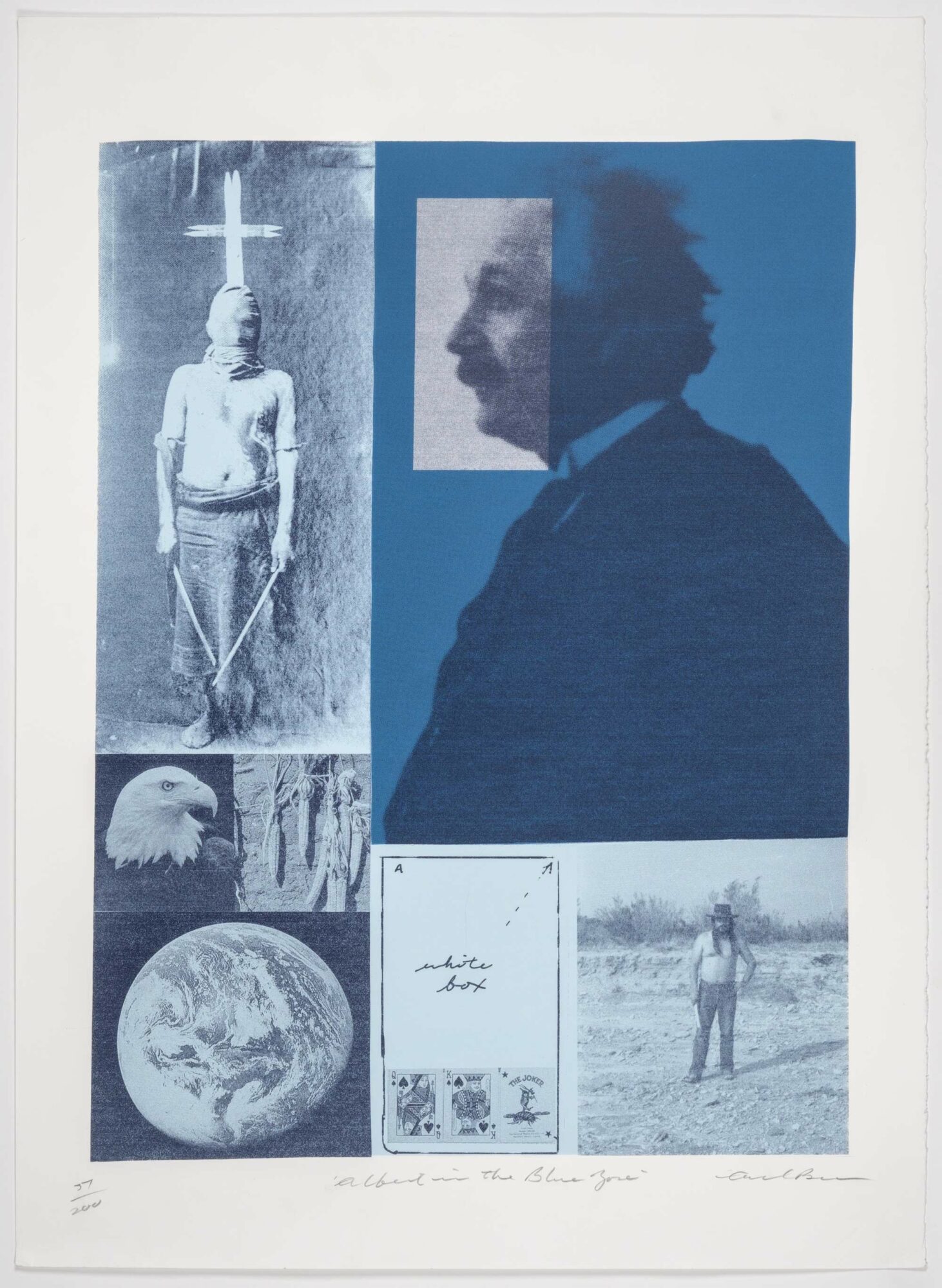

Beam’s wide study of Western thought—along with semiotics, he explored the philosophies of Martin Heidegger and Immanuel Kant, the modernist literature of James Joyce and Samuel Beckett, and the mathematical metaphysics of Stephen Hawking—provided fertile ground for examining the limitations of rationalism as an intellectual system. Images of writers and thinkers entered works such as Albert in the Blue Zone, 2001, which features a portrait of theoretical physicist Albert Einstein. Together, these pieces form a pantheon that represents the push and pull of the twentieth century.

Collage and Pop Art Influences

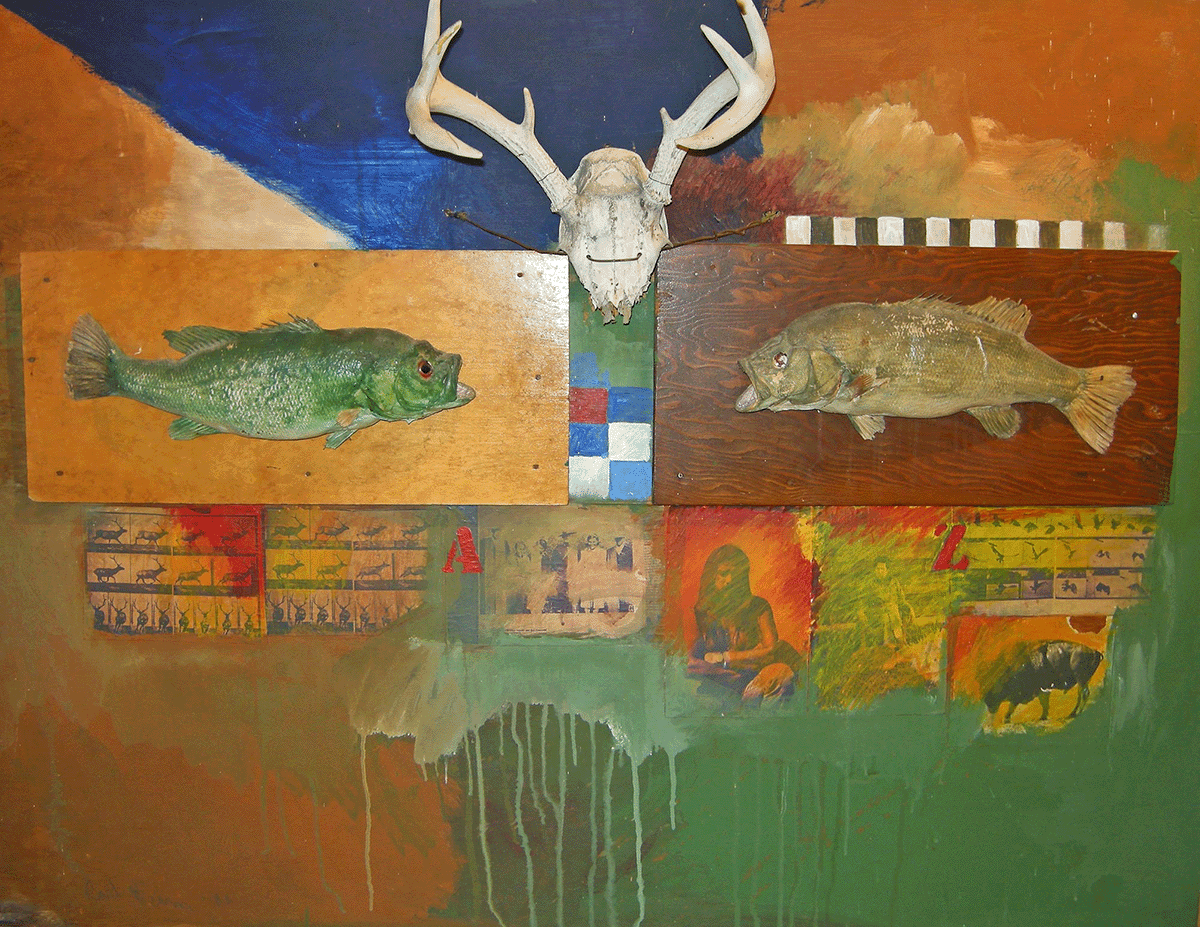

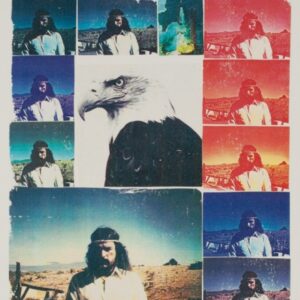

Beam received formal art training in the early 1970s, starting with a part-time drafting program at the Kootenay School of the Arts in Nelson, British Columbia. In 1974, he earned a bachelor of fine arts from the University of Victoria. It was during this time that he became acquainted with the techniques of contemporary innovators such as Andy Warhol (1928–1987), whose repetition of pop culture images mirrors Beam’s penchant for seriality, and Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), whose multimedia works built upon the techniques of early twentieth-century Dadaists. Beam’s early collage works, such as Stuffed Fish & Deer Antlers, 1983, resemble Rauschenberg’s “Combines” (large canvases incorporating found materials), as in Collection, 1954–55. Rauschenberg’s innovative collage-making strategy was an important reference point at a time when Beam was beginning to carve his own distinct path as an artist.

In collage, Beam found an image-making strategy that was in harmony with the principles of semiotics—namely, it allowed for the expression of open meaning. He was attracted to the idea that sign systems that are juxtaposed (collaged) in the same work could create multiple, dynamic, and allusive readings simultaneously. For Beam, collage forced the “reader” of his work to interpret meaning through clues supplied by the imagery, composition, and context. He valued the idea that the personal associations his collaged imagery stimulated in the viewer were perhaps more valid carriers of meaning than rational explanations of the relationships of one image, sign system, or visual vocabulary.

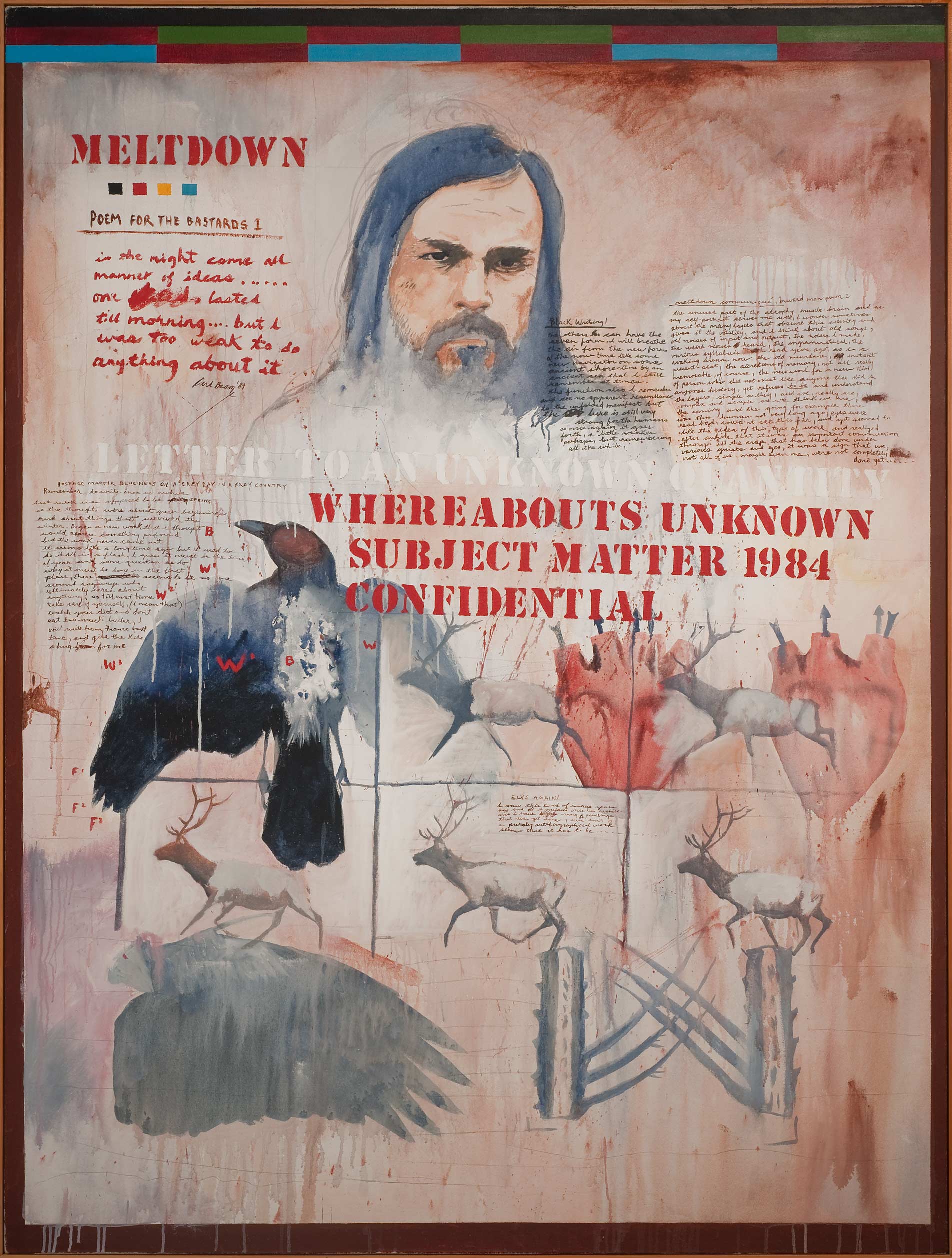

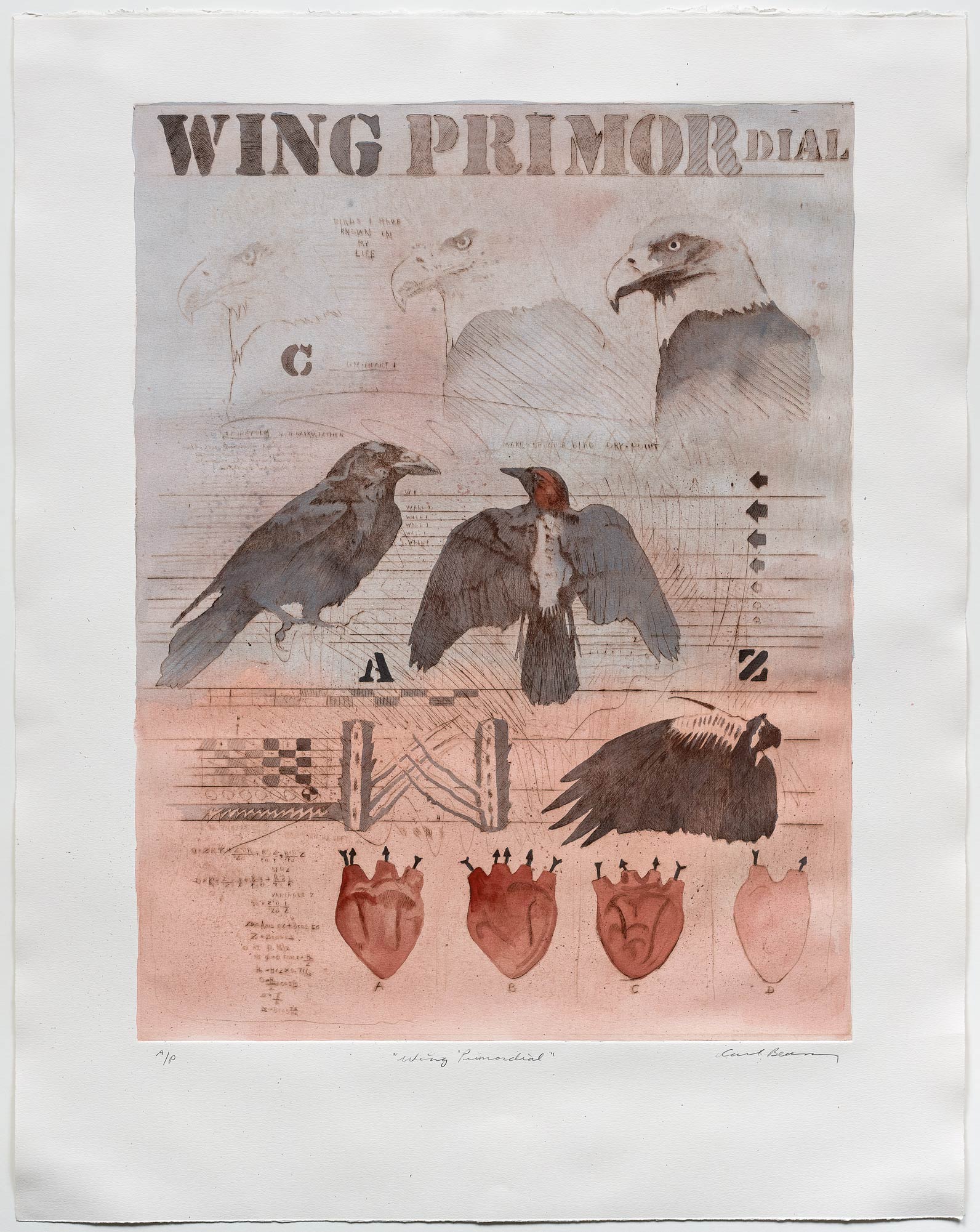

The large-scale painting Meltdown, 1984, deftly illustrates Beam’s use of collage methods across a range of media. Beam’s painted self-portrait features prominently within an image field defined by colour washes and handwritten and stencilled texts that emerge and recede into the pictorial space. Collaged images of running elk (sourced from photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s archive), as well as a bird, a heart, and other symbolic glyphs, are arranged in the composition. Many of these images also appeared frequently in works made in other media—the bird, for instance, is seen again in the earthenware bowl Parts of a Bird #2, 1985, and in the watercolour Untitled (Parts of a Bird), 1982. The seriality of Beam’s work served his interests in the subversion of meaning: the bird evokes different associations when juxtaposed with the running elk in Meltdown than it does illustrated on the inside of an earthenware bowl. Amid the various signs and scripts, Beam calls out to viewers to read the piece fragment by fragment, and to perhaps create a narrative whose meaning is entirely dependent on their own perspectives and the context in which they are experiencing the work.

Collage allowed for open-ended reading of his compositions in much the same way poetry and metaphor function. Beam’s artistic processes have been described as combining and recombining “visual and textual fragments from the past and present to interrogate history and illuminate contemporary experience.” Of the way he built his compositions—in a manner similar to composing spontaneous visual poetry—he stated: “Things have a power in and of themselves,… a peculiar emanation. The task of the artist is to set up a dialogue between objects.”

In addition to reflecting and complementing his ideas on semiotics, collage provided Beam with a visual form to express Anishinaabe cosmology. In 1989, he said, “We [the Anishinaabe] have the collage-like aspect to looking at life, which we could call cyclical—with no single viewpoint predominating.” This idea informs all his work in all media. Through collage, Beam created visual analogies of an entire worldview that seeks new meaning and forms of knowledge through the juxtaposition of seemingly disparate, irrational imagery.

Picturing Text

Beam’s interest in collage and semiotics can be regarded as an outgrowth of the harassment and violence he endured at Garnier High School in the 1950s. He considered the school to be a microcosm of society: a place where one’s worth—his worth—was based on the ability to speak, read, and write both English and Latin, and think in English and French. Those who could not were vulnerable. So, he forced himself to acquire these language-based skills to escape abuse. Later, he used text and language to deliver his messages like a Trojan horse.

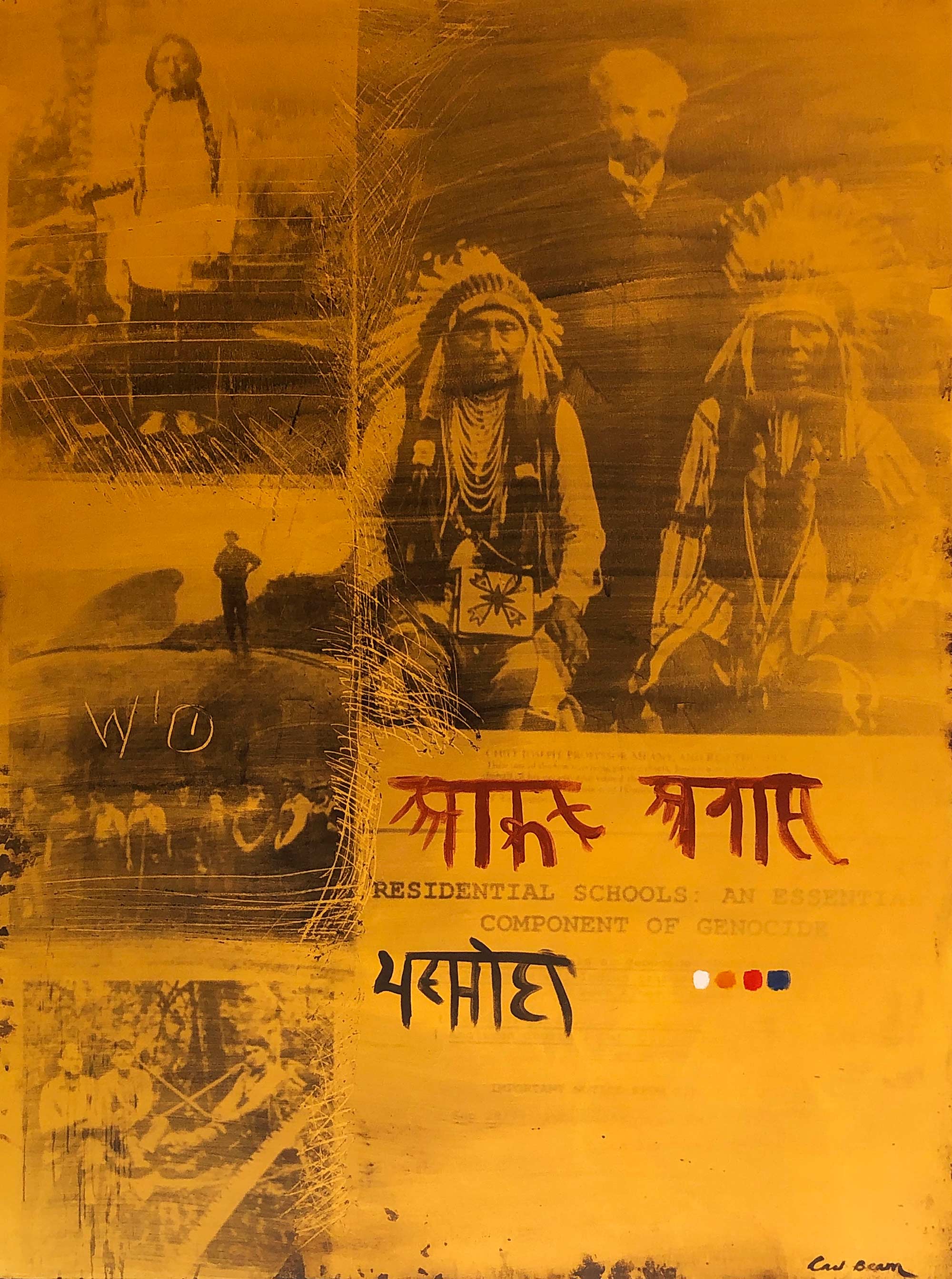

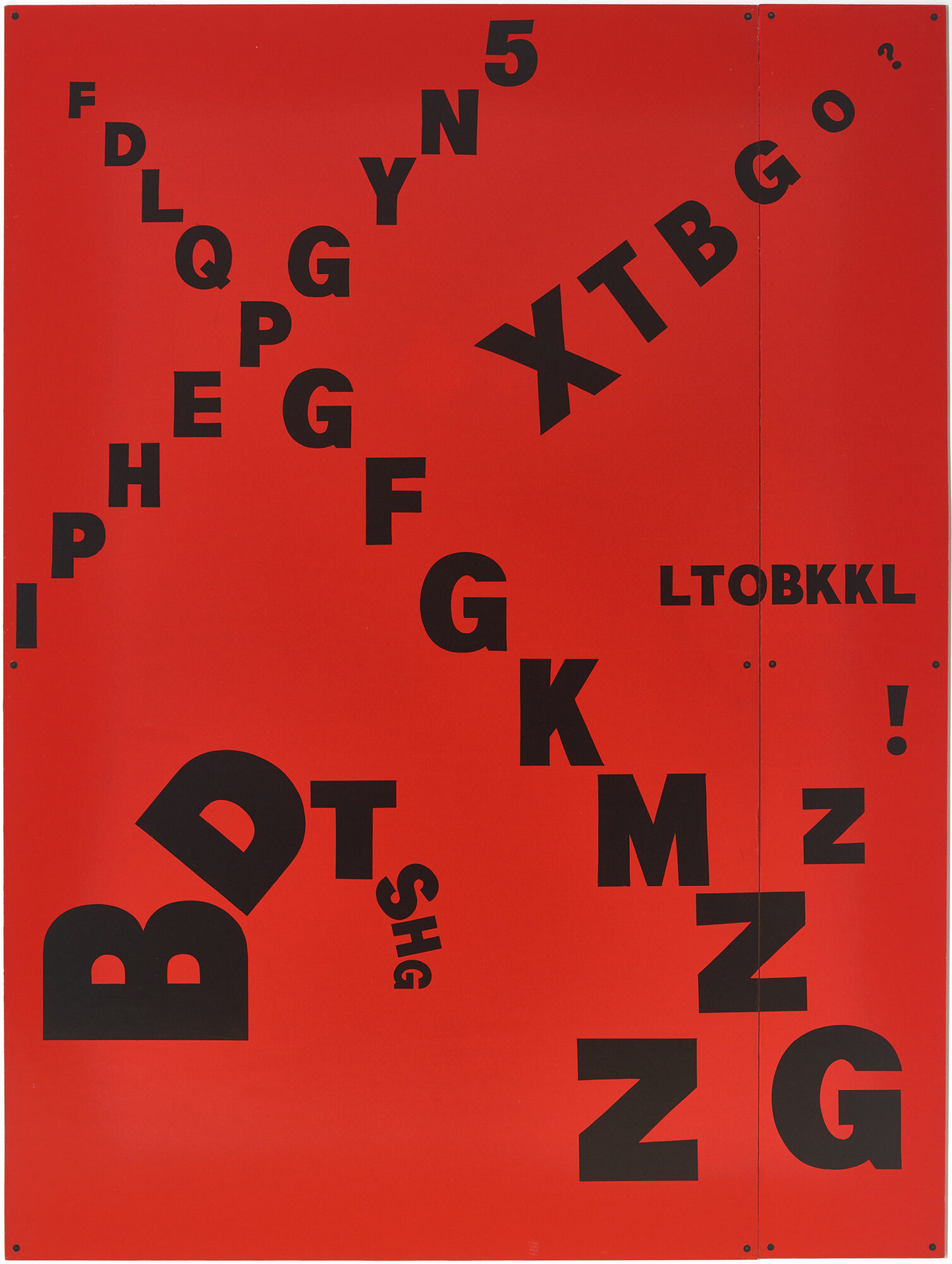

In large-format works such as Bashmi Cri (Reduced to Ashes), 1999, Beam uses the visual look of so-called foreign languages such as Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Ojibwe to provoke vulnerability. The work’s title, which translates to “reduced to ashes,” is written in Sanskrit over a glowing orange background with images of Indigenous chiefs posed with an Indian Affairs agent named Mr. Meany. Under the chiefs’ portraits is a screenshot of an early online forum entitled “Residential Schools: An Essential Component of Genocide.” Confronted with this combination of foreign text and collaged images, viewers, for a moment, would have to assume nothing. They would be forced to gaze upon the surface for clues to extrapolate meaning, and maybe, in this way, gain empathy or respect for the complexity of other language or thought systems.

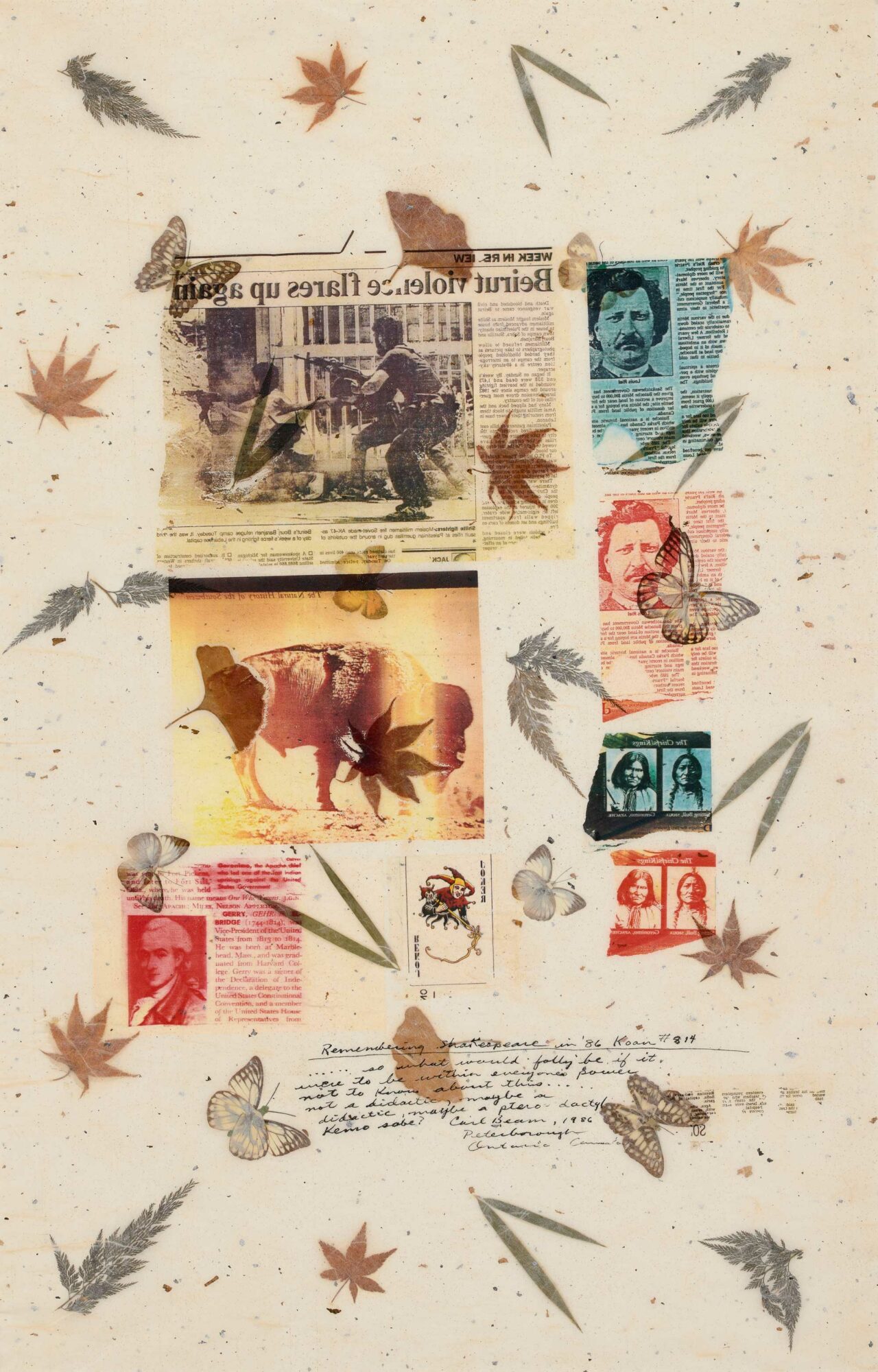

In picturing text, Beam worked in a manner like that of prominent Canadian conceptual artists such as Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) and Ken Lum (b.1956). Curnoe used stamps and stencils or handwrote fragments of text on the surfaces of his canvases, such as View of Victoria Hospital, First Series: #1–6, 1968–69. Meanwhile, Lum derived his 1980s series Language Paintings from the visual forms of billboards, often placing the onus on the viewer to decode any text presented. In contrast, Beam’s text-based works evolved from a deeply personal style. Lines of text in works such as Autumnal Idiocy Koan #814, 1986, were conceived as spontaneous prose—stream-of-consciousness writings in the manner of Jack Kerouac and other beat generation poets whom Beam admired and read. He called this type of writing a “koan”—referencing a Zen Buddhist form of dialogue meant to spur enlightened insight. His lines of text were never prearranged or preconceived. They flowed from his pen nib or brush directly onto paper, etching plate, or canvas. No erasing. No second thoughts.

It is this bracing immediacy and honesty that arrests viewers. The nearly inscrutable compositions, iconographies, and lines of text in works such as Bashmi Cri (Reduced to Ashes) compel the viewer—without thought—to the impatient, furtive reading we might have experienced as children, when we surreptitiously scanned someone’s diary and, in the process, invaded the person’s innermost feelings and thoughts without regard for their privacy.

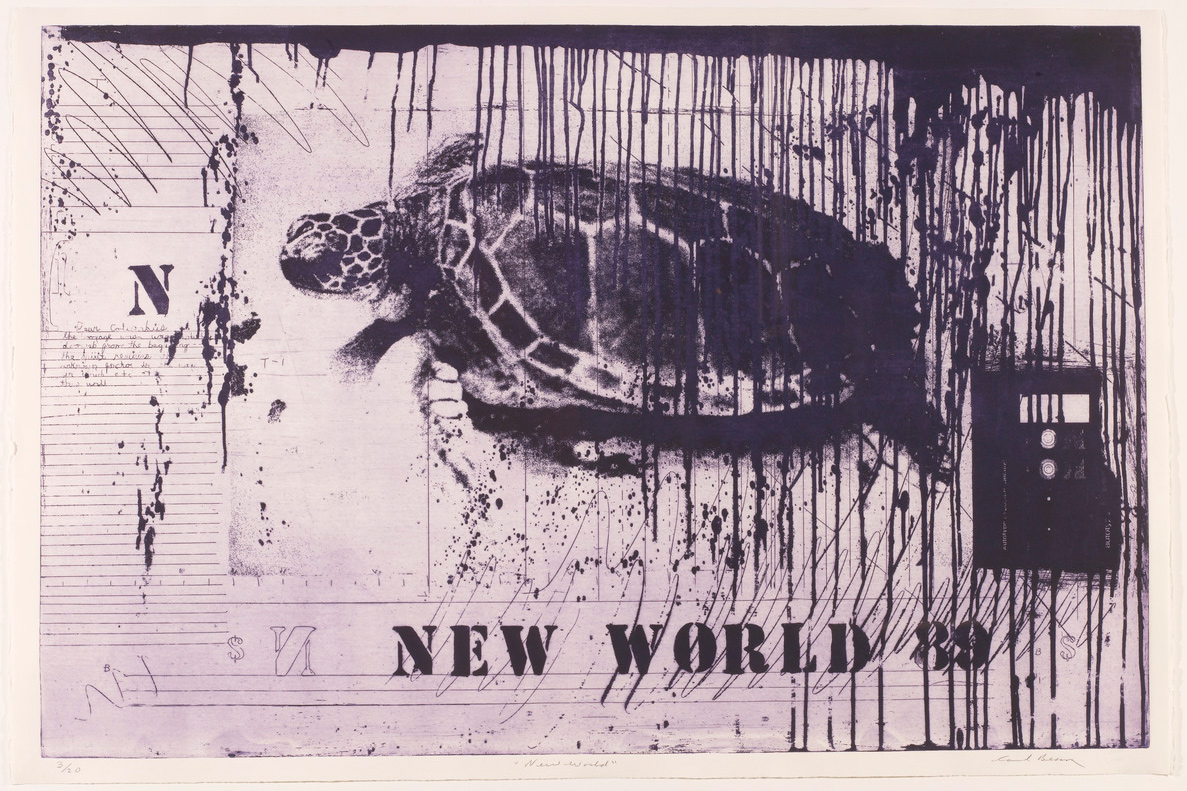

Words are inscribed on Beam’s work in black India ink, silver, gold, magenta, dark blue, and white, and always applied with lightfast inks, which he tested carefully to weed out colours that would fade over time. Occasionally, such as in The North American Iceberg, 1985, he changed colours and combined a frenetic script with a composed authoritative block of stencilled text overlaid with a grid, his other device of choice. New World (from The Columbus Suite), 1990, for instance, includes stream-of-consciousness prose written in cursive against a visual field with stenciled words and dripping ink. Such strategies reflected Beam’s belief that the dominant culture was obsessed with grid systems, in everything from pay to farming to measuring, to assume control over other humans and the natural world.

Photo Transfer and Printmaking: A New Poetic Language

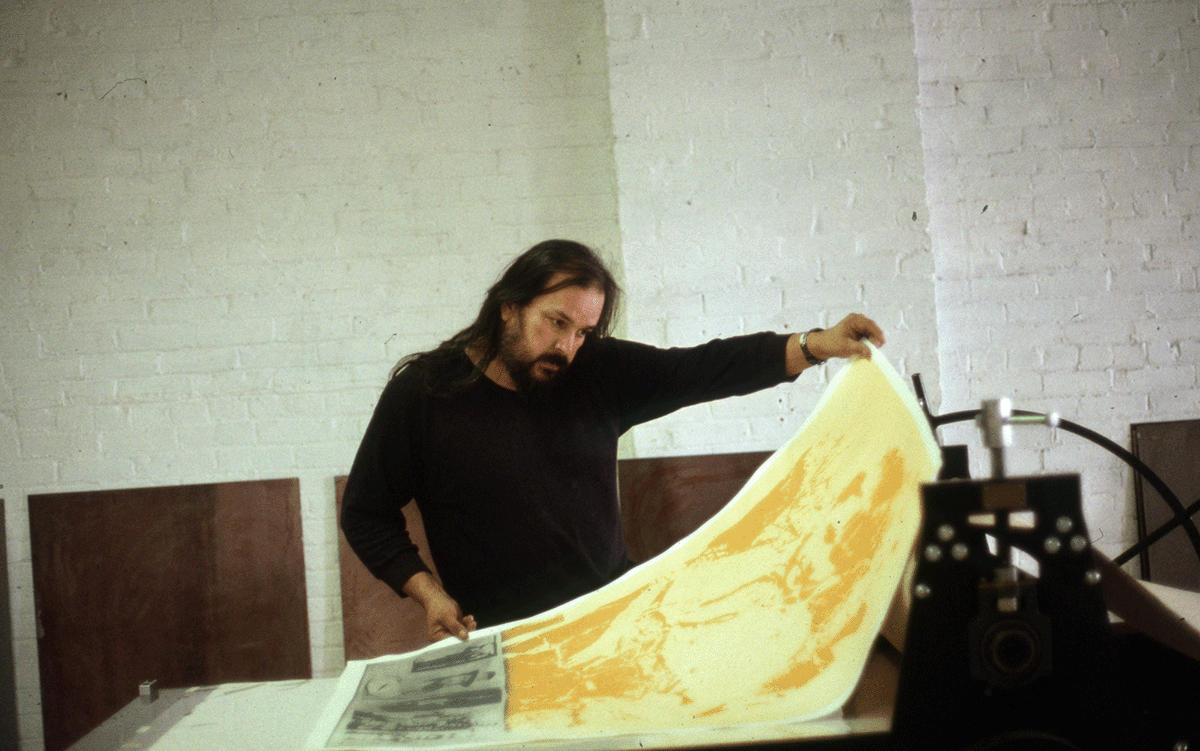

Through photo transfer and printmaking—etching and serigraphy—Beam developed innovative creative practices that supported his collage-making strategy. In 1983, shortly after moving to Peterborough, Ontario, he purchased a large etching press from Praga Industries—the only piece of furniture, besides the kitchen table and a futon, in the entire house at 222 Carlisle Avenue. With the assistance of his wife, Ann, Beam soon developed his first suite of etchings, The Zeitgeist Suite, 1983–84. This was a precursor to The Columbus Suite, 1990, and similar in size and scope.

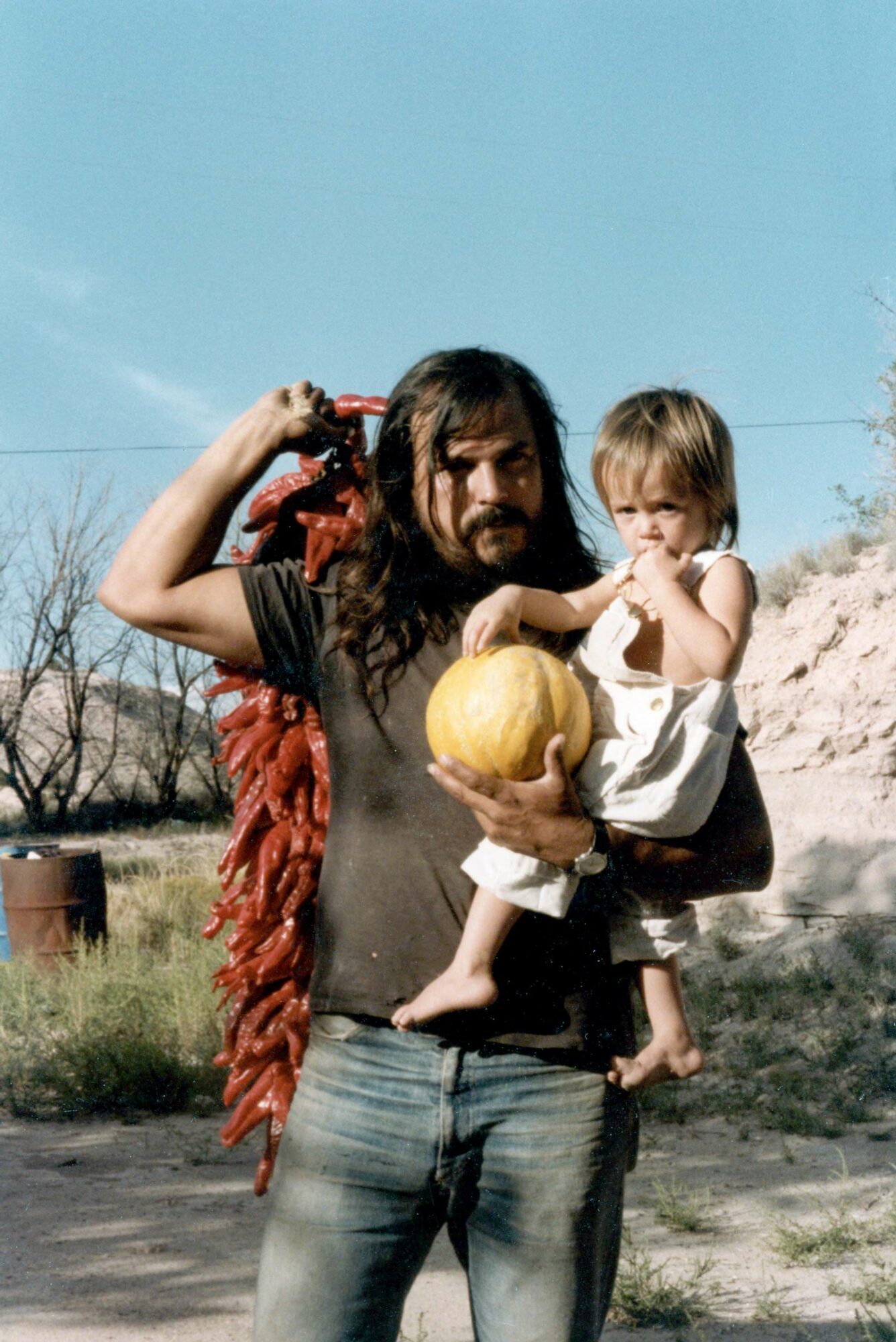

Also in the early 1980s, Beam began experimenting with the photo-transferring technique, which he used to reproduce images on a variety of surfaces, from watercolour paper and canvas to Plexiglas and cotton T-shirts. It was Ann who introduced him to this innovative process. Soon, Beam began to incorporate photographic materials into his mixed-media works, developing what he and Ann called “working images”—an archive of photographs taken from their family life and travels, as well as from museum displays, newspaper clippings, and textbooks. Beam also used a video camera to record the world around him, resulting in the performance piece Burying the Ruler, 1989, which provided additional still photographs that feature in several of his late-career photo-transfer works. From this point on, the working-images archive formed the foundation of Beam’s artistic practice, especially when involving collage.

In photo transfer, Beam found a potent method for producing visual poetry. It was readily adaptable and could be used to create radical juxtapositions of recognizable images—his own and those taken from contemporary print media. In this regard, Beam saw models to emulate in Pop art creator Robert Rauschenberg’s print collages. Beam was particularly inspired by Rauschenberg’s audaciously innovative lithograph Booster, 1967, which he saw on exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario. This print and its collaged image field turned Beam on to the poetic potential of creating radical juxtapositions in large-format print compositions. Works such as Various Concerns of the Artist, 1984, show the influence of Rauschenberg’s prints. For Beam, Rauschenberg was an innovator developing a new kind of poetic language that used text, images, and painterly devices, and in the process advancing the idea of what a poem could be: a visual statement as much as a textual one, whose meanings were as open-ended as they were allusive and metaphorical.

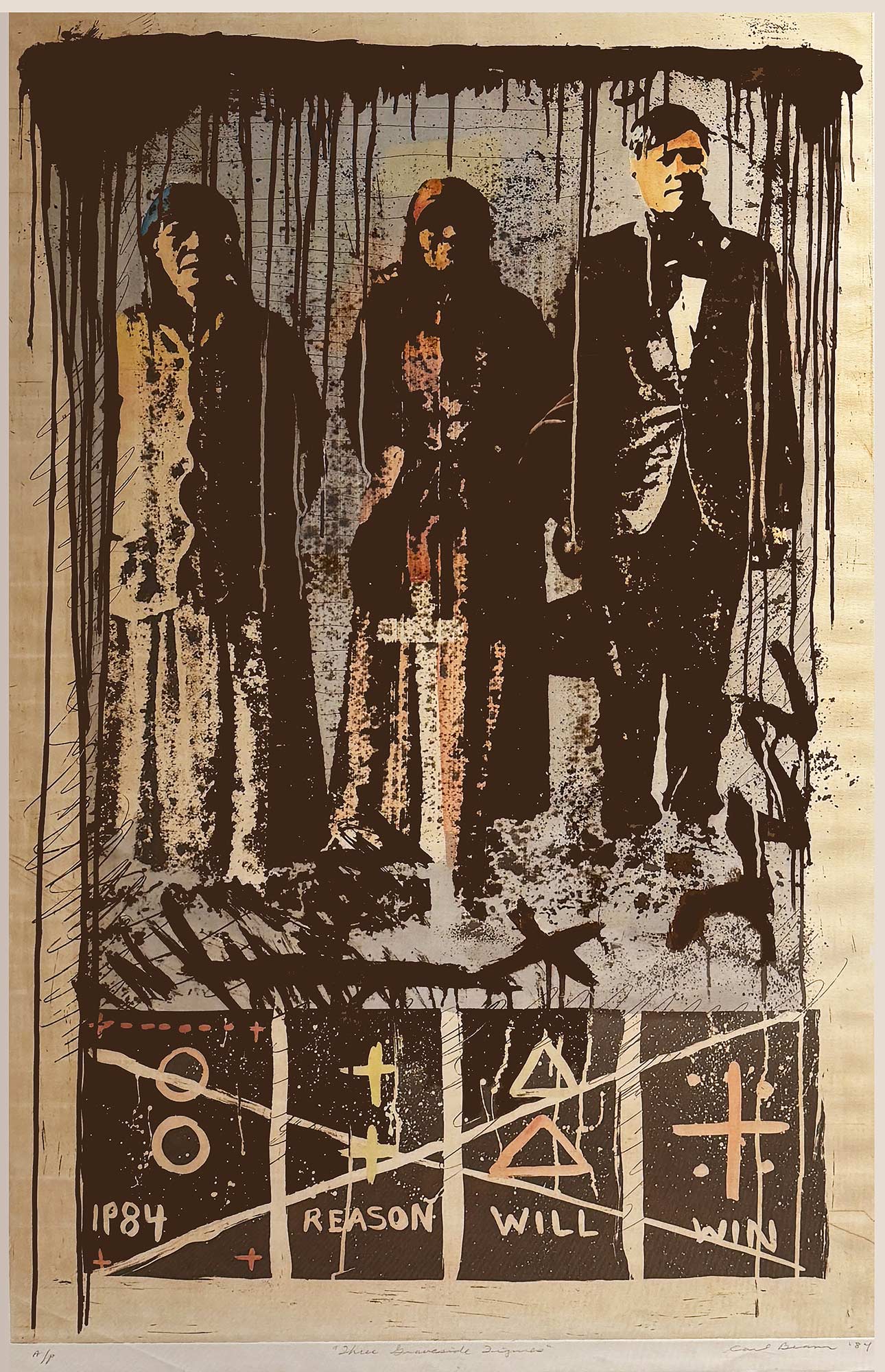

Beam’s printmaking process also used silkscreen negatives to reproduce imagery across different series. For instance, one screen for Three Graveside Figures, 1984, part of The Zeitgeist Suite, was used to print the same image in a positive polarity on the face of a sheet of Plexiglas forming part of The North American Iceberg. This same screen was later used to reproduce Three Graveside Figures, 1984, as a large-scale etching. The negative polarity images were printed directly onto steel plates using an asphaltum emulsion as if it were printing ink. These sequences of image flippings—starting with a negative image and ending with a positive one, thereby building imagery “backwards”—are a hallmark of Beam’s unique approach in most mediums. For example, by handwriting backwards on Plexiglas, Beam ensures the text becomes right-reading to the viewer.

Ceramics and Cultural Connection

My father’s love of ceramics was a constant presence in my recollections, especially in my early childhood. We would go into every museum, cultural centre, roadside shop, pueblo, kitchen. I remember watching him trade bearskins for tins of elusive black glaze used in Mimbres and contemporary pueblo designs. In all these places, he was looking for a connection to his own culture as well, documenting collections in Midland, Ontario, and at the Gardiner Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Everywhere he was told that the Anishinaabe, or Ojibwe, people did not have a ceramic culture. They and the Odawa were the traders of the region, and they obtained ceramics from the Mohawks to the south.

In the late 1980s, while my father was visiting family in M’Chigeeng, his young cousin came home from school with an interesting story. He and other local young people had assisted at an archaeological dig in Providence Bay on Manitoulin Island. He explained that they had found a bowl, and when my father asked what it looked like, the young man said, “It looked like the ones you make.” My father continued the search for this bowl, or any other indication of ceramic culture, but it was seemingly lost to the shuffling collections of archaeology. He also continued his explorations of Indigenous ceramic tradition, despite the many who repeated the line that it was not part of the culture. He felt a connection to this work and shared it with other artists, among them David Migwans, who was the most avid and skilled of the contemporary ceramicists.

Many years later, in 2017, when I was working for the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, I happened upon the pot that my father had heard about so long ago. It had been returned from a storage facility belonging to the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport. The castellated pot was a wonder to behold. Finely made and beautifully shaped, it was a prime example of the 126 vessel fragments that were discovered in the 1980 dig by archaeologist A.W. (Thor) Conway. The pots were indeed Ojibwe, as my father had presumed, and in the archaeological notes related to this vessel, there were descriptions of storage pits filled with processed clay formed into balls, ready to be shaped into pots and bowls. There was, in fact, a thriving Anishinaabe ceramic tradition—one that had been glossed over by academics and archaeologists for decades. Conway called the ceramics Algoma ware.

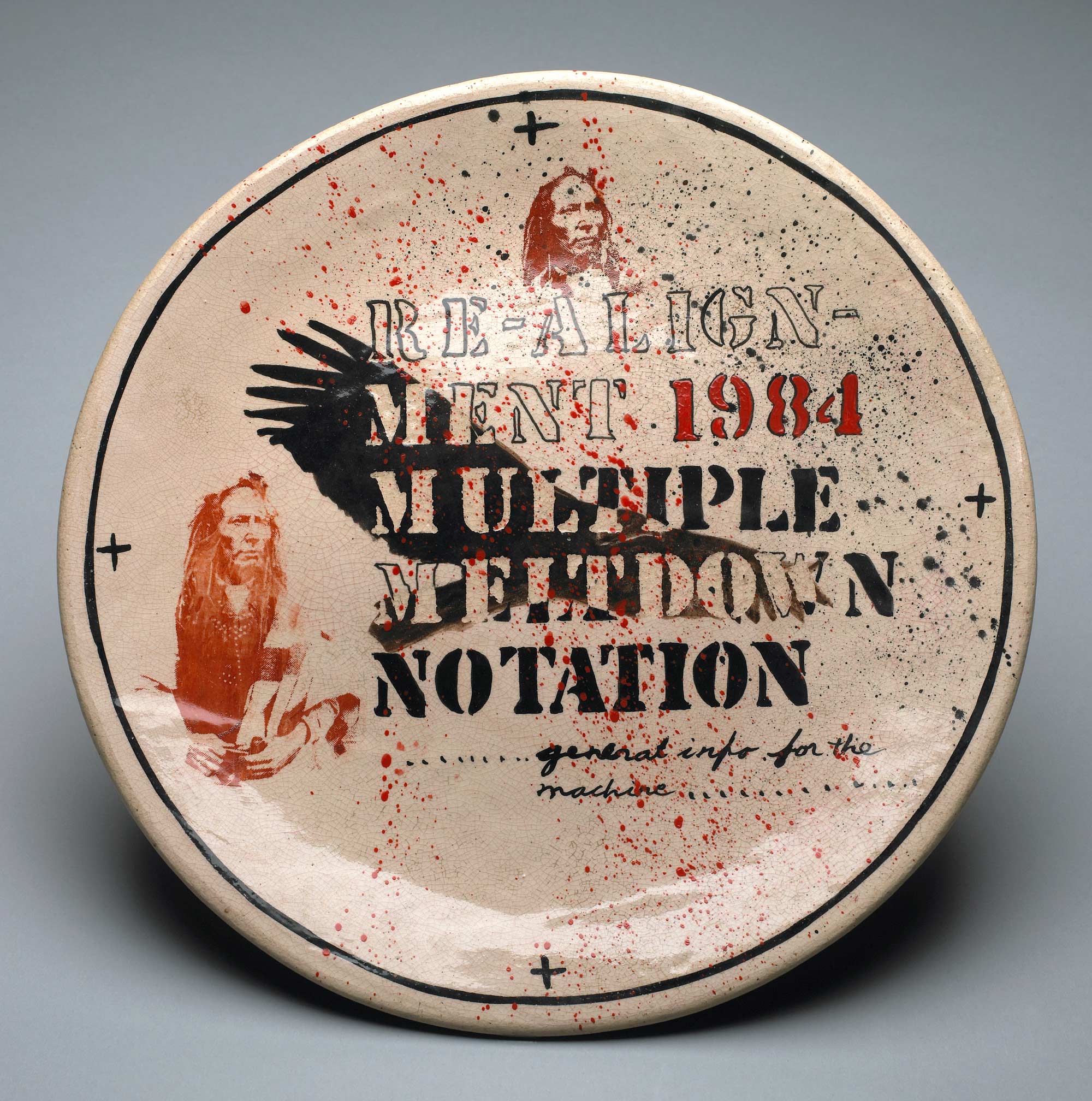

Ceramics were a significant part of Beam’s creative practice. From the time of his studies at the Kootenay School of the Arts and the University of Victoria, he was attracted to ceramics as a material for re-visioning history. His teacher, Frances Maria Hatfield (1924–2014), ignited in Beam a lifelong love of Asian ceramics. The shapes and forms of Kenzan-style Japanese ceramics, a type of raku-fired pottery characterized by delicate decorative glazes and brushed forms and named after the Kyoto-based potter and painter Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743), inspired his many experiments with the medium. But rather than appropriating Kenzan’s imagery, Beam infused his works with his own lexicon of signs and symbols. In the ceramic plate Re-Alignment, 1984, he juxtaposes a serialized portrait of Chief Poundmaker with a bird and the stencilled words “RE-ALIGNMENT 1984 MULTIPLE MELTDOWN NOTATION.” A piece of spontaneous prose written in Beam’s cursive reads “general info for the machine.”

While living in the American Southwest, Beam expanded his repertoire by studying bowls by the Mimbres and Ancestral Pueblo peoples. The strong graphic designs of these works and the contrasting surfaces of the vessels—rough outside and smooth inside—appealed to him to such an extent that he emulated these characteristics in his own ceramics. He was taken by the fact that these wares seemed to deny a chronological sense of history. Of these works, Beam later noted:

When I discovered they were done 1,000 years ago, I was completely surprised. For me this was it! Finally, one form I could use to be absolutely creative in, as had the Anasazi who had created these beautiful artworks, for they were nothing less than artworks. The hemispherical quality of a large bowl still excites me… like no cup, tea pot, plate or other clay shape can do. It is a universe unto itself, where anything can happen—the designs are limitless.

For Beam, ceramics were contemporary and yet rooted to long-standing cultural traditions—working with them could open the door to more fluid modes of expression. Once he and Ann embraced both the designs and hand-building techniques of Mimbres and Ancestral Puebloan ceramics, they were hooked. As Ann recalls, “Our pottery buzz continued until it reached an all-consuming frenzy.”

In 1982, just two years after Beam and his wife Ann relocated to the American Southwest, his ceramics caught the eye of Jerry Brody, curator at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico. Brody was impressed with the sheer creativity of the Beams’ wares, and he noted that they were “more like easel paintings than crafted objects, and for that reason raise many questions about our categories of fine arts, craft arts, and ethnic arts.” Indeed, with his ceramics, Beam broke down barriers like never before.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements